By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

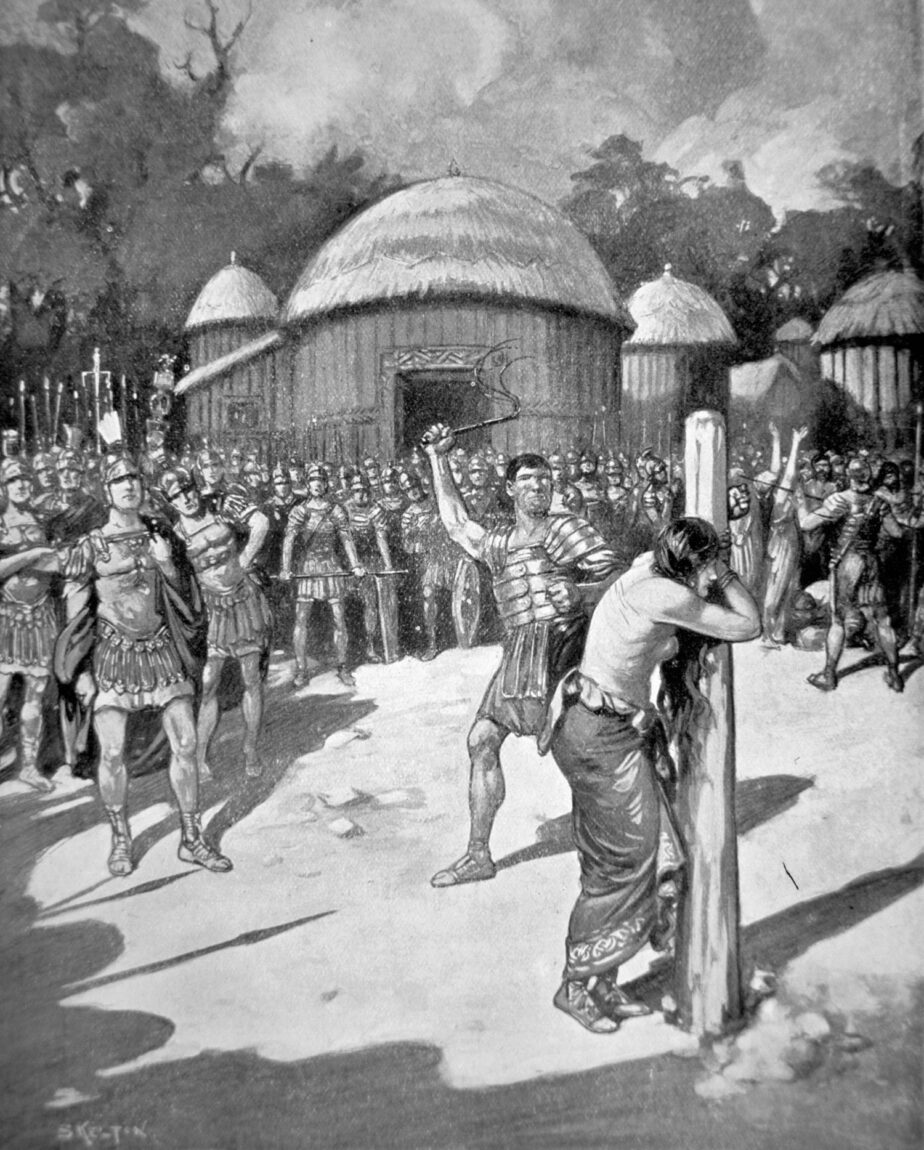

The lash bit into the flesh of the woman’s back, beaten raw by metal balls tied into the ends of leather thongs. Her arms bound to a post, she wallowed in a pool of her own blood. In the prime of her life, tall and athletic, her hair a tawny mass, she was the physical personification of a cultural ideal. She was Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, and her tormentors were servants and soldiers of the Roman Emperor Nero. Helpless, she had been forced to watch as her teenage daughters were raped. Eventually blood loss would have sent her into shock, blackness, and unconsciousness.

The renowned King Prasutagus had hoped to protect his wife, Boudicca, his daughters, and at least part of his Iceni kingdom (East Anglia) from the Romans. Although he was Rome’s ally and client king, Prasutagus feared complete Roman takeover after his death. Prasutagus had no male heirs, but he did have two daughters. When his long and prosperous life came to an end early in ad 60, Prasutagus’ daughters inherited his kingdom. To ensure Rome’s protection, Prasutagus named Nero as their co-heir.

Boudicca’s late husband’s goodwill meant nothing to the Romans. Surrounded by Roman provincial territory, the Iceni seemed ripe for exploitation. The greedy provincial financial administrator, procurator Catus Decianus, demanded the return of large sums of coin given to the Briton nobles by the late emperor Claudius. Similarly, Lucius Annaeus Seneca, the emperor’s chief secretary, had imposed a 40 million sesterces loan on the Britons and now demanded its return with heavy interest. Probably these cash grants were originally intended to fund the construction of Roman-style public works. The Iceni’s inability to pay served as justification for the Romans to annex the remaining portion of Prasutagus’ kingdom, which were the lands bequeathed to his daughters and ruled by their queen regent Boudicca. Servants of the emperor ransacked the households of the ruling families. Roman soldiers plundered the land. Avarice overcame good sense, for the Romans needed the support of the upper classes to maintain the peace. It was a horrendous error of judgment.

Back in ad 43, when Boudicca had barely come of age, her tribe was among the first to accept Roman alliance. The powerful neighboring Catuvellauni kingdom, which lorded over many of the southern tribes, had been defeated by Claudius. Camulodunum (Colchester), the sacred stronghold of southern Britannia, had fallen to Rome. Roman campaigns over the next four years expanded the frontier to the west and north. By ad 47, the frontier stretched from the Bristol Channel on the Celtic Sea northeast to the North Sea estuary of the Humber River. That year hostile tribes raided into the province. The Romans not only ruthlessly dealt with invaders but even disarmed friendly tribes. The Iceni resisted, but their brave efforts met with defeat. It was probably at this point, in order to retain his people’s freedom, that Prasutagus bound himself to Rome as a client king.

While Boudicca matured into a charismatic queen, a new generation of Britons came of age. “Nothing is any longer safe from [the Romans’] greed and lust … cowards seize our homes, kidnap our children, and conscript our men,” such were their common sentiments, according to Roman historian Tacitus. Iceni nobles, warriors, and rural tribesmen all were ready to follow Boudicca into battle. Fields remained unplowed and unsown, but forges blazed with the smithing of axe, spear, and sword blades.

Boudicca planned to strike directly at the heart of Roman Britannia by driving the Romans out of Camulodunum, which was the Roman provincial capital with tens of thousands of citizen settlers and Romanized Britons. After quashing the Iceni tribal coalition in ad 47, the Romans moved the XX Legion west from Camulodunum to fight the Silures of Wales. Camulodunum in turn became the first Roman colonia in Britannia, Victricensis (city of victory), settled by veterans on land seized from the Trinovantes. The veterans treated the locals like slaves, encouraged by a small number of remaining legionaries who looked forward to the same privileges. The Britons believed that whoever held Camulodunum would invoke the blessing of the Celtic war god Camulos. To add insult to injury, their sacred stronghold became the provincial seat of the Imperial Cult. The Roman temple was a blatant manifestation of despised foreign rule. The Trinovantes and others were ready to revolt with Boudicca, who welcomed their aid.

The Romans thought the Britons so cowed that they let the walls of Camulodunum’s legionary fort fall into neglect. Only a few hundred legionaries remained in the XX Legion’s former camp. In addition, a smaller camp held the 1st Thracian cavalry wing. Then there were several thousand veterans, many of whom could still be counted on to put up a fight. Wedged between two rivers to the east and a system of dykes to the west, Camulodunum, if properly fortified, would have had some hope of fending off Boudicca’s army. But there were no strong fortifications, and without them the strength of the defenders would mean nothing to Boudicca’s multitude.

Boudicca proudly ascended a raised platform of earth to face an ocean of humanity. More than 100,000 Briton men and women, veterans and youngsters, looked to her for inspiration. Her hair cascading down to her hips, her eyes fierce and wild, her hands grasping a spear, Boudicca was tall, beautiful, and terrifying. She was dressed in a tunic of many colors. A thick mantle with a golden brooch accentuated her shoulders. A golden necklace adorned her neck. Her harsh voice stirred the hearts of her followers: “Let us show them they are hares…trying to rule over wolves,” wrote Roman historian Cassius Dio.

She protested of impoverishing Roman taxes and urged her warriors to fight for the freedom of their children. To Boudicca, the Roman helmets, breastplates and greaves, their walls and their tents only showed their fear and their weakness to the elements. The Britons fought on home ground and needed only their shields and their valor. In a form of divination, Boudicca released a hare from the fold of her dress. The Britons roared in approval when the hare hopped to what was considered the favorable side. According to Dio, Boudicca raised her hand toward the sky and prayed to the Celtic war goddess, “I thank thee Andraste and call upon you woman to woman … I pray to thee for victory.”

At Camulodunum many ominous signs were said to have occurred. The statue of victory fell down, landing with its back turned as if fleeing, and “delirious women chanted of destruction,” wrote Tacitus. The native uprising could not have come at a worse time for the Romans. As Boudicca was well aware, Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and the XIV Gemina Legion were away on a summer campaign against the last great druidic stronghold on the island of Mona (Anglesey). The only reinforcements that reached Camulodunum in time were from Londinium (London), likely the base of procurator Catus who sent barely 200 poorly armed troops.

Resident Britons at Camulodunum, secretly in cahoots with Boudicca, downplayed the seriousness of the impending danger. The temple defenses at Camulodunum were deemed adequate for whatever was to occur. No rampart was built up and no trench dug and no plans made to evacuate the old people and the women. “Their precautions were appropriate to a time of unbroken peace,” noted Tacitus.

Boudicca’s mighty army swept upon Camulodunum. The Roman defenders fell back to the temple precinct where they were joined by terrified civilians. For Boudicca there was no mercy for the conquered. The Britons ran amok, looting and killing, through streets and blocks that once housed soldiers but whose barracks had been converted into civilian lodgings. Barricaded within the inner temple sanctuary, soldiers and civilians huddled around the life-sized bronze statue of Claudius. After two days the temple was burned to the ground with its occupants inside.

Too late did more help arrive. Closing in on Camulodunum were 2,000 legionaries of the IX Hispana with cavalry support. Cerealis Caesius Rufus had conducted a forced march from Longthorpe to the northwest. Boudicca’s Britons stormed out of the city, engulfing Cerealis’ soldiers. Leaving his doomed infantry to be slain to a man, Cerealis and the cavalry fled back to Longthorpe.

News of the disaster at Camulodunum spread throughout the province. Fearing for his life, procurator Catus boarded a ship and set sail for Gaul. Catus’ example was emulated by upper class citizens who could afford sea passage. Londinium’s usually crowded riverbank docks soon stood empty.

Governor Suetonius was busy demolishing the druid groves on Mona when news arrived of Boudicca’s rebellion. One of Rome’s leading commanders, Suetonius had previously crushed a Moor uprising in Africa. In the conquest of Mona, Suetonius had sought an equal to his rival Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo’s reconquest of Armenia. Suetonius’ men had faced black-robed women, their hair wild like that of the Furies, who brandished torches while druids, according to Tacitus, raised “their hands to the heavens and screamed dreadful curses.” Suetonius recalled the faces of his legionaries, paralyzed with superstitious fear at the sight of fanatical women, until, urged on by their centurions, the legionaries had charged forward to destroy the enemy “in the flames of their own torches.”

Again it was a woman, Boudicca, who was Suetonius’ most formidable foe and who gave the misogynist Romans, in Dio’s words, “the greatest shame.” Leaving a garrison on Mona, Suetonius marched his army through northern Wales to the military road of Watling Street. Crossing south-central Britain, he reached Londinium. There he hesitated. Suetonius had brought his men through rebellious lands but so far encountered no noteworthy opposition. But Boudicca’s vastly greater army was approaching from the northeast.

The defeat of Cerealis’ IX Legion weighed heavily on Suetonius’ mind. Like Cerealis, Suetonius would be facing insurmountable odds if he engaged Boudicca at Londinium. Rejecting pleas to stay and defend, Suetonius decided to sacrifice, relates Tacitus, the “single city of Londinium to save the province as a whole.” Instead of continuing southward from Londinium over the River Tamesa (Thames) and into the rich southern lands with their Channel trade posts, Suetonius doubled back along the military road. An exodus of civilians accompanied the departing Roman army.

Boudicca’s horde poured into the defenseless city. Flames and destruction spread from the city’s center on Cornhill west to Lugate Hill. Tragically, the majority of Londinium’s remaining citizens were the women and the old. The Britons slaughtered all. The most horrible tortures were inflicted upon the noble and distinguished women, according to Dio. If not killed outright, female captives were taken to sacred groves of Andraste and other deities. In what may have been particularly brutal religious rites, or Roman exaggerations of events, their breasts were chopped off and sewn into their mouths. The victims were impaled by stakes “lengthwise through the entire body,” according to Dio.

The terror continued for one week after another. Boudicca’s horde grew in power and ravaged undefended settlements, bypassed strongly held forts, and followed in Suetonius’ wake. Verulamium (St. Albans) was the next to fall. Boudicca took no prisoners to sell or exchange for those of her own. Blood sprayed from slit throats, bodies dangled from ropes, and flames engulfed everything living or dead. Roman citizens and provincials killed were estimated at 70,000 to 80,000. Dio wrote that the “island was lost to Rome.”

Suetonius was doing all he could to make sure Britannia stayed Roman. He had called to service veterans of the XX Legion as well as gathering the nearest available auxiliaries. The II Augusta Legion at Isca Dumnoniorium (Exeter) too was ordered to come to Suetonius’ aid, but its commanding officer, camp prefect Poenius Postumus, refused.

Suetonius’ column had been swelled by more refugees from Verulamium. By the time he reached today’s Warwickshire, the food supply for his army was getting low. Ahead lay the frontier of Roman Britannia. Within a few days of marching Suetonius would be in Brigantes lands. Although their queen, Cartimandua, was a steadfast ally of Rome, her realm was ripe with Roman antipathy.

Since the day the Britons acknowledged her their war leader, Boudicca had doubled the size of her army. Her victories had won over more tribal factions. Boudicca’s army moved slowly, not only because of all the looting, but because families in lumbering wagons tagged along. Boudicca must have been wondering what Suetonius was going to do, either stand and fight or venture into hostile territory. She found him with his army holding up in a defile. The refugees had fled in other directions. Boudicca decided that the time had come for the decisive battle.

Boudicca looked upslope at the Roman army, upward of 10,000 strong, positioned with a wood behind them, holding higher ground. Steeper slopes on either side of the Romans prevented any outflanking by the Britons. However, the Roman position would also hinder any chance for the Romans to escape.

Perhaps some 2,000 XX Legion veterans and some 4,000 legionaries of the XIV Legion held the Roman center. More than 2,000 auxiliaries flanked the legionaries on either side. Among them were archers, light skirmishing troops, and cavalry on the far wings, including Batavi from the Rhineland. The Batavi had fought alongside the XIV Legion for decades. All the Roman divisions where deployed in deep ranks that could not easily be penetrated. Facing them, Boudicca drew up her army. The chiefs in their chariots and their warriors formed the front ranks to encourage the poorly armed farmer-soldiers that made up the majority of Boudicca’s army. To the rear, their families remained with the wagons, hollering in encouragement.

The image of Boudicca standing proud and defiant in her chariot, her daughters at her side, became an icon of British nationalism. Driving along lines of fervent warriors, Tacitus relates that Boudicca cried, “We British are used to woman commanders in war … though descended from mighty men, I am not fighting for kingdom and wealth but for my lost freedom for my bruised body and my outraged daughters … the gods will give us the victory we deserve!” “The Roman legion that dared to face us is annihilated … they will never face the din and roar of our thousands … you will win this battle or die, that is what I, a woman, plan to do!”

Tacitus says Suetonius likewise addressed the stalwart lines of the legions: “Disregard the clamors and empty threats of the natives … in their ranks there are more women than fighting men. Throw your javelins, and then carry on: use shield-bosses to fell them, swords to kill them. When you have won you will have everything.”

With a great roar, Boudicca’s mighty host strode forward. Dio gives 120,000 men for Boudicca’s army at the beginning of the rebellion and 230,000 at the final battle. Although Dio likely embellished the size of Boudicca’s army, she may well have commanded a fighting strength of up to 50,000 alongside tens of thousands of noncombatants.

Spontaneous battle songs broke out among the Britons, their voices reverberating up toward the Romans. The Roman troops stood their ground, with many a legionary in silent prayer to his ancestors and to Mars, god of war. The legionaries drew deep breaths to maintain their calm until the shouts of their centurions and the drone of Roman trumpets released them into action. With the Britons no more than 60 yards away, a storm of javelins erupted from the cohorts. The javelins thudded into the flat, hide-covered oak shields of the Britons and tore into their ranks.

In wedge formation, the cohorts charged into the Briton masses. Heavy iron bosses of legionary shields pummeled Britons to the ground. Blank gladii stabbed downward. On the flanks, the earth shook with the charge of the Roman auxiliary cavalry. Their spears lowered, the Batavi overwhelmed their foes. The Roman forces cut into the enemy ranks but by doing so exposed their own flanks. Routed or slain Britons were replaced by others coming up from behind them and threatening to envelop the Romans.

The battle broke into confused separate melees. At one point Briton chariots scattered Roman troops only to be repulsed by a hail of arrows from Roman auxiliaries. “Horseman would overthrow foot soldier and foot soldier strike down horsemen,” wrote Dio. Though no record has been left of Boudicca’s actions during the battle, it is tempting to picture her in her chariot, hurling javelins, like Andraste incarnate.

At last the Britons’ valor collapsed into flight, but their way was blocked by their own wagon rampart. Bunched up with their families, yelling and screaming, the Britons desperately clambered over the wagons and each other and through panicked draught animals. The Romans butchered everyone, men and women alike. Even the baggage animals were “transfixed with weapons,” wrote Tacitus, adding “to the heaps of dead.” The battle merged into a slaughter, lasting until late in the day.

Tacitus described Boudicca’s defeat as “a glorious victory, comparable to bygone triumphs.” Roman reports estimated up to 80,000 Britons killed, not differentiating between warriors and noncombatants. “Our own casualties were about four hundred dead and a slightly larger number of wounded,” wrote Tacitus. When news of the battle reached Isca Dumnoniorium, II Legion commander Postumus was overcome with shame. For missing the chance of being part of such a victory, Postumus “stabbed himself to death.”

Boudicca escaped along with a sizable number of Britons. There are different accounts of her death. Tacitus wrote that she poisoned herself in despair. According to Dio, Boudicca grew ill and died. But sudden illness seems an unlikely demise for such a vigorous woman. Possibly she had sustained wounds during the battle, and these had become lethally infected. Her end near, she thus chose suicide. Boudicca was greatly mourned and given a worthy burial by her followers. Her valiant efforts continued to inspire the tribes. Despite the casualties suffered, many refused to surrender.

Suetonius united the whole army, including the II Legion and the remaining units of the IX Legion, and recruited eight new auxiliary infantry cohorts. A further 1,000 cavalry were summoned from Germania, alongside 2,000 legionaries to replenish the IX Legion. Any hostile or wavering tribes were crushed. To compound their misery, the Britons’ decision to go to war instead of planting grain resulted in famine. The tribes nevertheless held on until, in ad 61, the vengeful Suetonius was replaced by the more lenient governor Publius Petronius Turpilianus. Turpilianus achieved an uneasy truce, ushering in a decade of peace.

In the aftermath of Boudicca’s failed rebellion, the influence of the Iceni nobility was reduced to a small tribal community based around Venta Icenorum (Caistor St. Edmunds, Norwich). The area remained under military occupation until the governorship of Gnaeus Julius Agricola. With civilian administration, the Iceni regained some form of their own government. The Roman garrisons were transferred north to Camelon to fight new wars.

Boudicca’s popularity was undeniably due to her charisma, her energy, and her passion, traits that her generalship did not live up to but for which Boudicca would ultimately be remembered. A symbol of freedom, her heroic statue, complete with teenage daughters, chariot, and rearing horses, graces London’s Thames embankment even though she once brought about the city’s destruction. After Boudicca’s death, there would not be another uprising by the tribes of southern Britannia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments