By Kevin Mahoney

Aviation militaria has always been popular with collectors, representing a fascinating aspect of 20th-century warfare. Among the more interesting items in this realm are the medals and flight log books from the airmen of the British Royal Air Force and Commonwealth Air Forces of World War II. Both are tangible representations of the savage aerial combat in which these men fought.

The decorations they could be awarded included: for officers, the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC); and for enlisted men, the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal-Flying (CGM-Flying) and Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM). Both groups of men could qualify for the highest valor decoration, the Victoria Cross (VC).

During World War II, approximately 1,100 DSOs, 21,000 DFCs, and 6,600 DFMs were awarded. These could be made as either “immediate” awards in recognition of a specific act of gallantry, or so-called “periodic” awards that recognized gallant conduct over extended periods. The number awarded by any command of the RAF, such as the Fighter Command that fought the German Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain in 1940, was strictly limited by the British Air Ministry.

The larger number of DFCs than DFMs awarded is owing to several factors. As in any military hierarchy, officers were often more likely to have their service recognized by the award of a decoration than was a member of the enlisted ranks. Pilots, many of whom were also officers, also often received recognition because they were the captains of an aircraft and responsible for the success of a mission and the fate of the crew. Since many British bombers had only one pilot after 1942, they were expected to remain at the controls of severely damaged aircraft to allow other crewmen time to bail out, thus greatly reducing their own chances for survival.

In addition, a pilot could be awarded the DFC upon successfully completing a tour of operations, an award called a “survival gong” (a “gong” being contemporary slang for a decoration). Awards of the DFM, however, were also made to pilots because many RAF and Commonwealth pilots began as noncommissioned officers. Generally an immediate award of the DFM was considered by many airmen to be the equivalent of a DSO.

The 103 CGMs and 22 VCs awarded to RAF and Commonwealth airmen during World War II were, for the most part, immediate awards for a specific heroic act. The VC awarded to RAF bomber pilot Leonard Cheshire in 1944, however, was in recognition of prolonged heroism during his hundred “operations,” or combat missions, over enemy territory.

A final award, ranking below the decorations already listed, was the Mention in Despatches (MID). It comprised the inclusion of the name of an airman who had contributed to combat operations in a list issued by the Air Ministry and published in the London Gazette, the official publication of the British government for laws and legal notices. A small oak leaf insignia, worn on the ribbon of the War Medal awarded for service in World War II, was used to denote an award of the MID.

The London Gazette was, in fact, the place where all RAF awards were published during World War II. Citations could be included, particularly for awards of the VC, CGM-Flying, and “immediate” awards of the DFC and DFM. An example of an immediate award of the DFM is that awarded to Flight Sergeant T.W.J. Hall in the spring of 1944.

Hall had joined a Lancaster bomber squadron in March 1944. After flying on his first combat mission as second pilot with an experienced crew to gain familiarity with operational flying, he took his own crew on their first night raid against Berlin on March 24. Arriving at the German capital early, Hall circled the city in the face of intense German antiaircraft fire to approach it a second time when marking flares could be seen. He successfully bombed the target then turned for home.

Unfortunately the wind on this night was blowing from a direction that had not been forecast, and many bombers, including Hall’s, were blown off course on the return trip, eventually flying over the industrial heartland of Germany, the Ruhr, which was ringed with intense antiaircraft defenses. Illuminated by searchlights, his Lancaster was hit by flak in the left wing, rear turret, nose, and both port engines, one of which caught fire. Evading the searchlights, Hall was able to extinguish the fire in the engine, feather it, and land safely at his home base.

He was recommended for the DFM for his “cool determination” during the mission, but regrettably did not live to receive the medal. He was killed several days later on the infamous raid on Nuremberg in which 95 bombers were lost.

Many RAF air crew that successfully completed a tour of operations never received a decoration, although one was often richly deserved. Their only reward was the campaign stars issued to servicemen of all the British and Commonwealth armed forces. The only such star reserved for RAF air crew was the Air Crew Europe Star, awarded to those who had flown in combat from England over occupied western Europe before the spring of 1944. A proposal for a star for the gallant airmen of the RAF’s Bomber Command who bombed Germany for five long years and of whom approximately one-half were killed, was turned down.

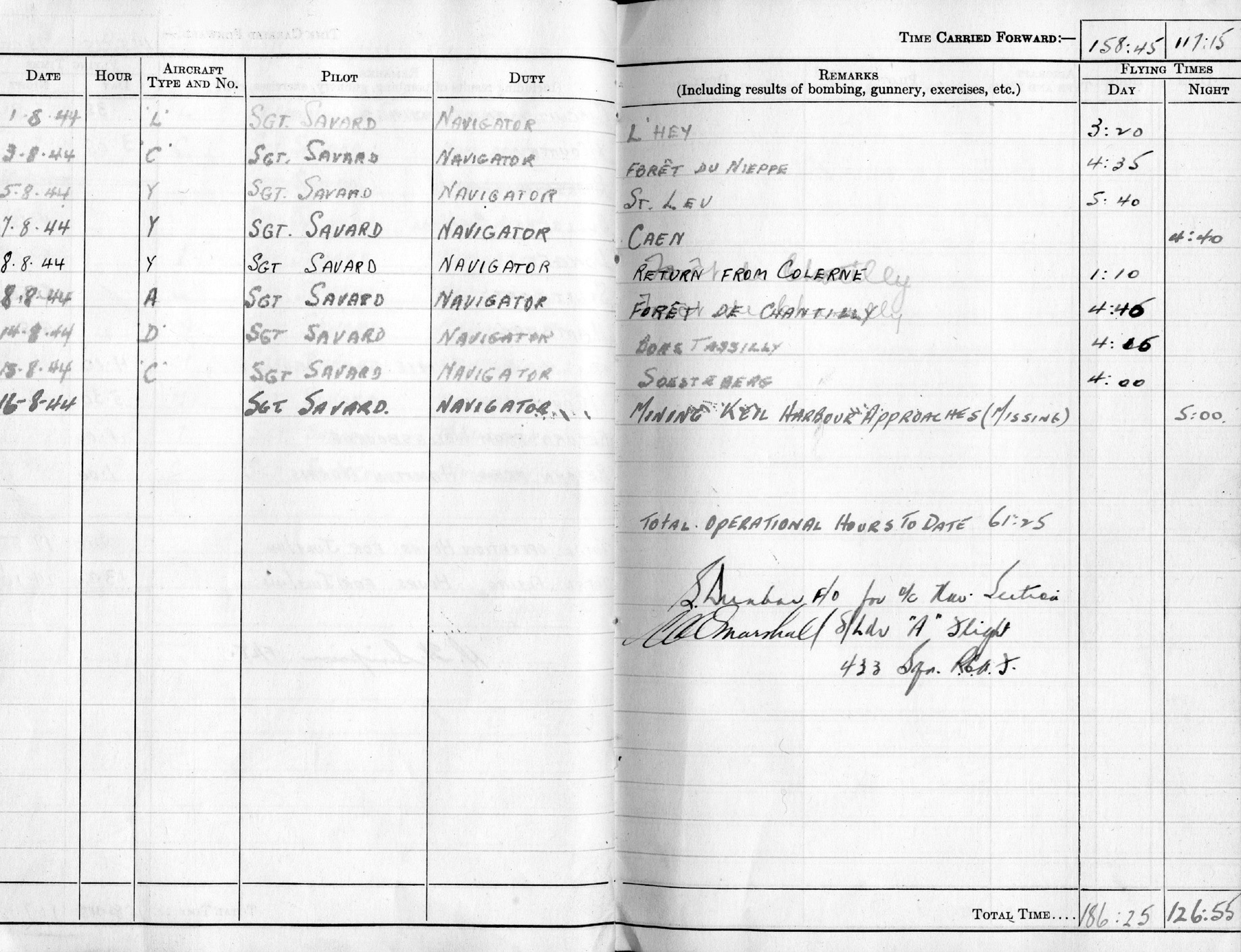

The combat career of an RAF or Commonwealth Air Forces air crewman can be traced from the log book that often accompanies the medals he was awarded. This blue-covered book contains the official record of a man’s military flying career, certified every month by his commanding officer. Each log is different, reflecting the personality of the man who kept it.

A log book can sometimes be a diary of sorts, in which a flyer wrote details of a mission. All contain RAF slang of the period, which is often quite descriptive. A “prang” could be used either to describe the successful bombing of a target or the crash of an aircraft. The laconic phrase “duty carried out” is often found as the only indication that a mission was successful, part of the understatements about combat operations often found in log books. Combat missions are often written in red ink to differentiate them from noncombat flights, and some air crew also used red ink to describe night combat missions and green ink for daylight combat.

Pilot’s log books are about twice as large as those of air crew and offer more space for comments. Thus a pilot’s log book can often have more information about a mission, with notations about enemy flak and fighters and the success of the mission. But the strain of flying could also lead to cryptic, though often quite poignant, comments. After the notorious Nuremberg Raid, mentioned earlier, a Canadian pilot who completed the mission simply noted “Operations to Nurenberg [sic]. No future in this—94 [lost]” in his log book.

Another interesting example of log-book understatement is found in the work of a Royal Canadian Air Force bombardier, officially called an Air Bomber in the RAF and Commonwealth Air Forces during WW II. On a night-bombing raid over the German city of Kassel in October 1943, his Halifax four-engine bomber was shot up by a German night fighter, killing the rear gunner and wireless operator (radioman), and wounding the flight engineer.

During evasive action to avoid the fighter, a two thousand-pound bomb fell from the aircraft but the bombardier was unable to jettison the remainder because the control cables had been shot away. As the aircraft turned for home, he dressed the wounds of the flight engineer and took over his position for the remainder of the flight. Although badly wounded, the flight engineer managed to regain consciousness several times during the flight home and instruct the bombardier how to perform the engineer’s duties on the return flight.

When the bomber reached its base, the crew was ordered to abandon the aircraft rather than trying to land it. The pilot chose instead to land in order to speed the wounded flight engineer to a hospital. He brought in the plane safely and the flight engineer survived. The pilot was awarded an immediate Distinguished Flying Cross, and the flight engineer received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal-Flying.

The bombardier’s log book entry for the mission reads simply “Ops-Kassel, one 2000 lb, thirteen sbc,” the last two notations indicating the bombs carried on the mission: one two thousand-pound bomb and 13 small incendiary bombs. As this example shows, a little research can often reveal a fascinating story behind a terse entry for a combat operation in a log book.

Unfortunately, some decorations and medals have been reproduced and offered for sale as originals. A good reproduction of the Distinguished Flying Cross has appeared, as has the Air Crew Europe Star. In fact, all of the British Campaign Stars from World War II have been reproduced, and very closely resemble the originals.

Log books may be found that are marked as “duplicate.” This was not uncommon because the log was the official record of an airman’s flying time, an important commodity to a flier, and a duplicate was often kept in the event the original was lost. A duplicate usually does not contain the commander’s monthly endorsement, and the absence of this signature is a good sign that a log is indeed a duplicate. It is, however, an authentic contemporary document.

British and Commonwealth log books and medals can be purchased from major medal dealers, many in the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. A log book for air crew, such as a gunner, flight engineer, and so on, with combat service, can start at $200, while those of pilots are more highly sought after and hence more expensive.

Campaign stars begin at $15; the rare Air Crew Europe Star usually brings $125 or more. Log books with decorations and medals such as the DFC and DFM from the same flier generally cost in excess of $1,000 while those with a DSO or CGM are considerably more expensive.

Generally, the price for a group of campaign medals with log book from the same flier begins at $300. Those of airmen killed in action can bring a higher price. All such groups, with the personal history associated with them and the conflict they represent, comprise an interesting area of militaria collecting.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments