By Roy Morris JR.

Seemingly from birth, William Haines Lytle was bound for glory. As the last surviving male offspring of one of Cincinnati’s leading pioneer families, Lytle was the prototypical golden boy. Blessed with good looks, a winning personality, and a verbal facility that enabled him to begin reading at the age of four, he was groomed from the start to fulfill a special destiny. By the time he was 16, Lytle was one of the most popular young men in the Queen City. His adoring sister Lily was not alone in believing that he was destined one day to become president of the United States.

Politics, poetry, and the law vied for Lytle’s adult attention, but his special interest—like that of his great-grandfather, Captain William Lytle—was the military. At the age of three, he was painted in a full uniform with a dress sword hanging at his side; a year later he received his first gun. Short and slender (he was five feet, six inches tall), Lytle nevertheless had inherited his namesake’s love of fighting. The old captain had fought successively against the French, the British, and the Indians on the western frontier before settling down near Lexington, Kentucky. His son, also named William, moved to Cincinnati in 1806 and built a handsome mansion on the outskirts of the city, from which he presided over the upper reaches of Cincinnati business and cultural life. The younger Lytle was a patron of the arts, commissioning John James Audubon to paint his and his wife’s portraits and donating a princely $11,500 to newly founded Cincinnati College. World-famous songwriter Stephen Foster was a distant relative.

Lytle Joins the Army

William Haines Lytle, called Will, was born on November 2, 1826. His father, Robert Lytle, was more interested in politics than the military. Dubbed “Orator Bob,” he was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1828 and the United States House of Representatives four years later. A lifelong Democrat, Robert Lytle was a personal friend of future presidents James K. Polk and Franklin Pierce, and his son Will was dandled on the lap of President Andrew Jackson. (Young Will returned the favor by toddling about the family mansion shouting “Jackson!” at the top of his lungs—an early indication of his own political instincts.) Orator Bob’s political fortunes waned as Jackson lost popularity after his stand against the Bank of the United States, and he lost his reelection bid to Whig challenger Bellamy Storer in 1830. Jackson immediately appointed him U.S. surveyor general, a position previously held by Robert Lytle’s father.

When Will Lytle was 13, his father died of tuberculosis; his mother died two years later of the same disease. As the man of the house, Will became a father figure for his two sisters, Josephine and Lily. Both girls worshiped him, particularly Lily, the youngest of the children. With the help of his maternal grandmother, Margaret Lytle, Will kept the family together, living in the mansion and staying in Cincinnati to attend college rather than matriculating at Princeton, his mother’s choice. After graduating first in his class from Cincinnati College in 1843, Lytle studied law with his uncle, Ezekial Smith Haines, one of the city’s leading attorneys, receiving his law degree four years later.

By that time, the Mexican War was at its height, and Lytle enlisted in the army, where he quickly won election to the rank of lieutenant in Company L, 2nd Ohio Volunteers. By the time he reached Mexico, however, the war was already winding down, and Lytle was denied the opportunity to draw his sword in combat. Instead, he spent most of his time futilely politicking for a staff position with General William O. Butler of Kentucky, an old family friend who perhaps inadvertently alienated the proud young officer by receiving him “with a hauteur which I could not brook even in a Major Genl.” When he was promoted to captain a few months later, Lytle observed with some satisfaction that now he enjoyed a position “which elevates me above [Butler’s] favor or charity … he and his staff may both go to the devil.”

Lytle in Politics

Returning home to Cincinnati in July 1848, Lytle resumed his legal practice and political aspirations. After surviving a near-fatal case of cholera, he reclaimed the family legacy by winning election to the Ohio House of Representatives. “William H. Lytle—the worthy son of noble sire,” proclaimed one campaign banner. Another neatly encapsulated Lytle’s appeal: “Small in body but big in soul.” To his uncle Edward Lytle the newly elected representative promised: “My political career shall be free from all impurity and have but one guiding star [,] a sincere and holy ambition to promote the true interest of the people.” When Kentucky senator Henry Clay’s funeral cortege passed through Cincinnati in July 1852 en route to his final resting place in Lexington, Lytle was the youngest man selected to accompany the procession. Riding a white horse on a Mexican saddle covered in silver, Lytle made a striking figure. According to his sister Lily, “Everyone talked about how handsome he looked.”

Adding to his romantic image, the gray-eyed, long-haired Lytle cultivated a citywide reputation as a patron of and participant in the finer arts. He attended museum openings, high-flown operas, and gala society balls, and once took the role of Hamlet’s ghost in an amateur performance of the play. He also became a connoisseur of fine wines, some of which were locally produced in Cincinnati, and developed, in the careful words of one scholar, “the gentleman’s weakness for drinking.” He spent a number of less exalted nights playing billiards with his friends in the rough-and-tumble Irish Hill section of town. Reports of his disreputable conduct, perhaps planted by political enemies, appeared in local newspapers, and Lytle’s Uncle Edward scolded him in a letter: “I would ten thousand times sooner have heard of your death. My scorn of rowdyism and vulgar debauchery is and always has been inexpressible.” Lytle assured his uncle that the reports of his roistering were greatly exaggerated.

Part of Lytle’s discontent may have been the result of a series of romantic disappointments. He showed a certain aristocratic propensity for falling in love with his cousins, beginning with his first cousin, Lily Macalester, the daughter of his father’s sister, Eliza. Lily’s father, prominent Philadelphia businessman Charles Macalester, opposed the courtship from the start on the unimpeachable eugenic grounds that the two were close relatives in a family plagued by tuberculosis, but he also found Lytle’s public escapades unacceptable. The couple broke off their two-year engagement in 1853, and Lytle moved on to a more distant cousin, Sarah Elisabeth “Sed” Doremus, the niece of New Jersey governor (and Lytle kinsman) Daniel Haines. In early 1855, Lytle asked Sed to marry him, but she declined. Apparently expecting to be asked again, she was devastated when her punctilious suitor abruptly ended the engagement. Lytle wrote wistfully to his sister Lily, who rather liked Sed, “Love, that star with me has set forever.” Sed, for her part, vowed never to marry before Lytle did—a vow she would keep for the rest of her life.

From his mother Lytle inherited a love of poetry, and he began writing verse in his early teens. His first poem, written in 1840, was “The Soldier’s Death.” His Mexican War service inspired the poems “Popocateptl,” “Jacqueline,” and “The Volunteers.” His best-known poem, which quickly became one of the most popular drawing room pieces of the 19th century, was the lyric “Antony and Cleopatra,” which Lytle dashed off one afternoon at his home while recovering from a serious illness. Its memorable opening line, “I am dying, Egypt, dying,” became a catchphrase in both Northern and Southern homes during the decade before the Civil War. After it was published in the June 19, 1858, issue of the Cincinnati Commercial, Lytle, like the rather more talented Lord Byron before him, “awoke one morning to find himself famous.”

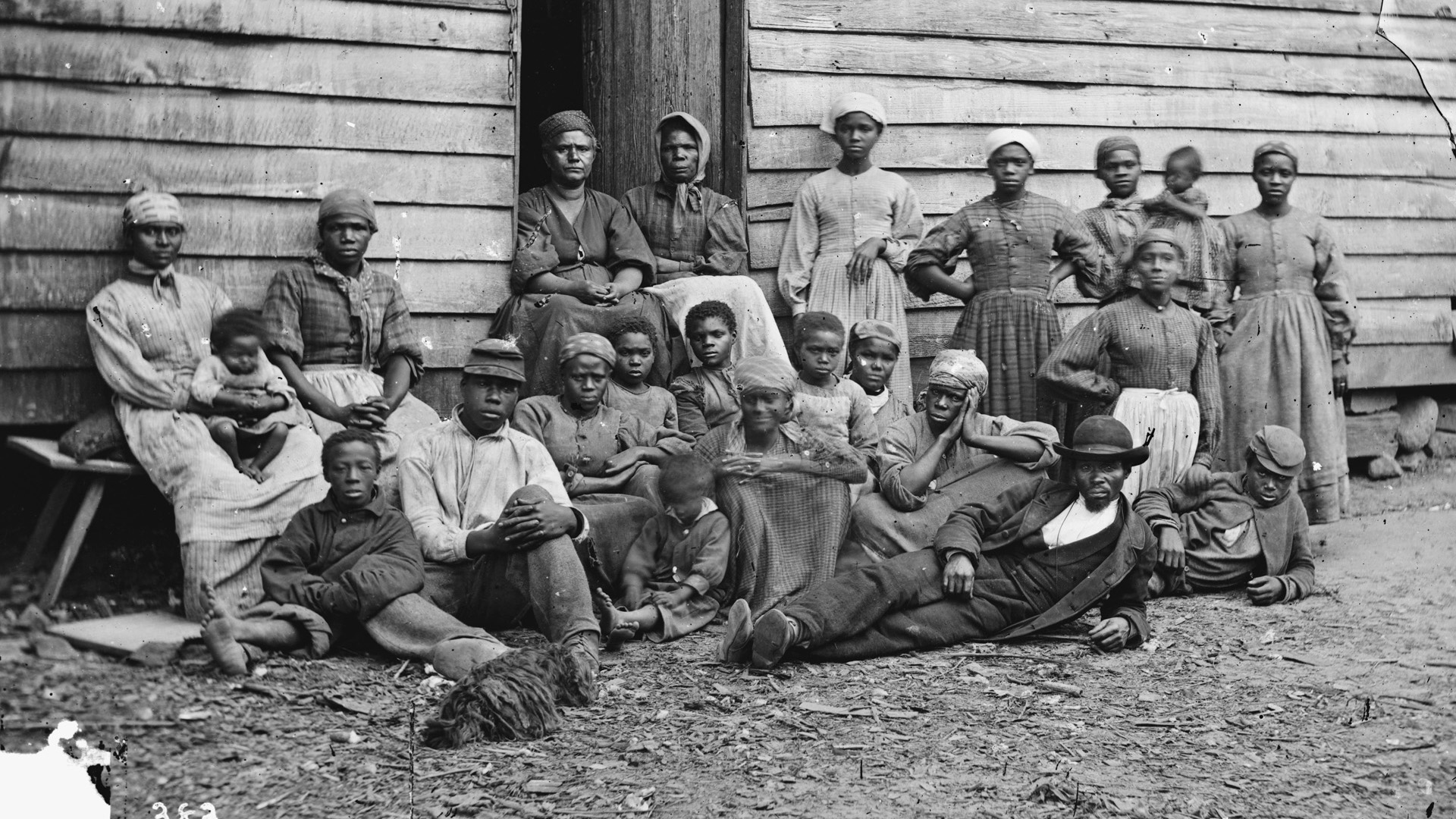

Lytle left the state legislature in 1853 to concentrate on his legal career, joining his Uncle Ezekial and his good friend Alex Todd in the law firm of Haines, Todd & Lytle. He turned down offers to run for Congress or to serve as President Pierce’s secretary to Chile. In 1857, he narrowly missed being elected lieutenant governor of Ohio, a loss probably attributable to his strong support of the recent, controversial Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court, which rejected the notion of citizenship for African Americans. “The black Republican party,” warned Lytle, would eventually drive patriotic Southerners out of the Union, since “their self respect will not permit them to remain.” The abolitionists, he advised, “should keep cool and not tear their linen.” Three years later, after failing to win the Democratic nomination for Congress, Lytle campaigned vigorously for party presidential nominee Stephen Douglas in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent the election of Abraham Lincoln and the very departure from the Union by outraged Southerners that Lytle and others long had foreseen.

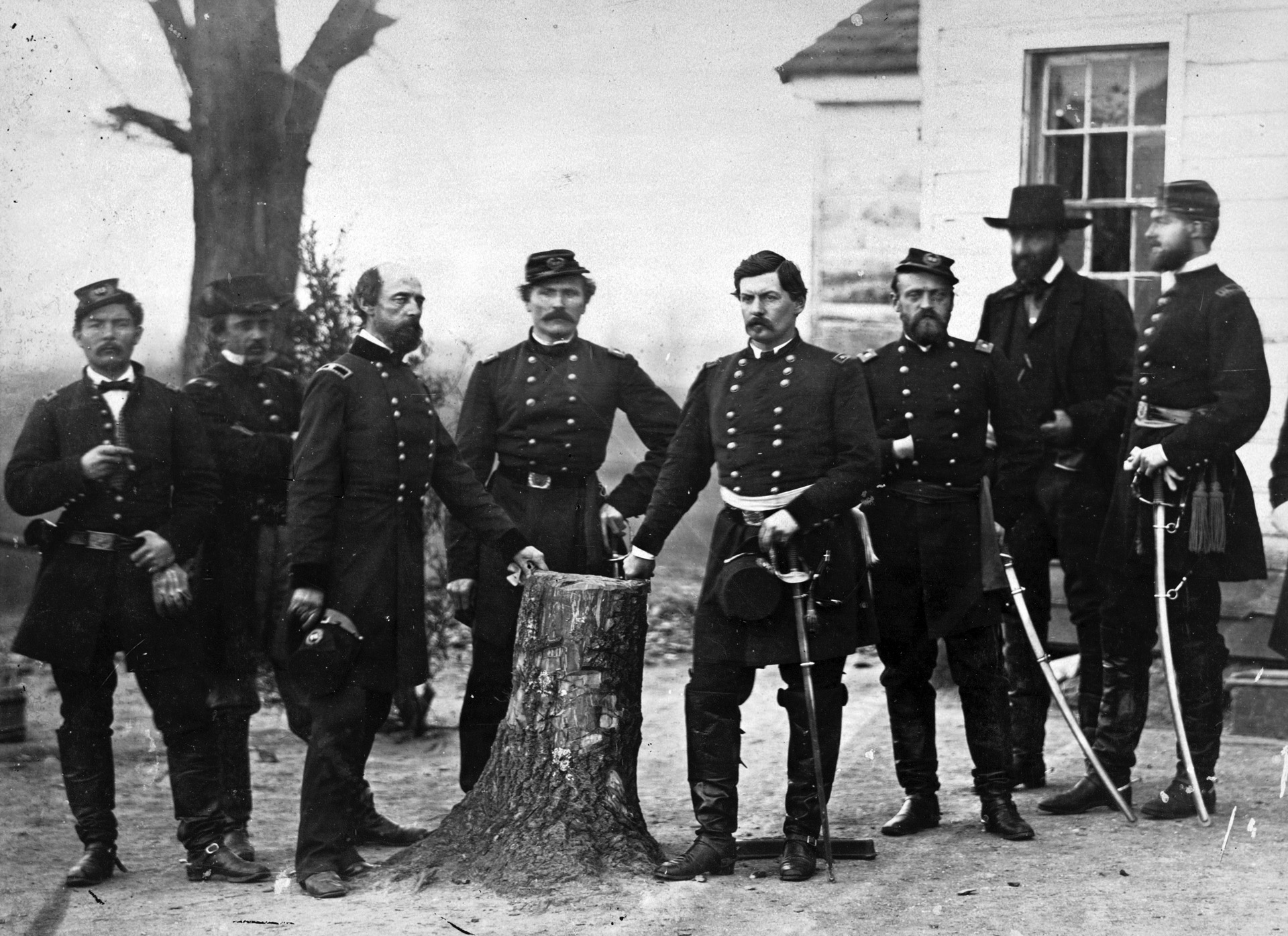

Colonel of the 10th Ohio Infantry

Lytle had remained active in military affairs, rising to the position of major general of the 1st Division, Ohio Volunteer Militia. One month after the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, he resigned his militia post to accept a commission as colonel of the 10th Ohio Infantry, a regiment recruited largely from Cincinnati’s sizable Irish community. His previous experience helped him whip the rowdy, hard-drinking regiment into shape at Camp Harrison, a training facility located seven miles outside the city. In appreciation of his untiring work and diligence, his colleagues in the Cincinnati Bar Association presented Lytle with a handsome ceremonial sword; other friends made him the gift of a spirited black charger with the Gaelic name Faugh-a-Ballaugh, or Clear the Way. In June 1861, the young colonel accepted a stand of regimental colors sewn by the patriotic women of Cincinnati and promised to return the flag “to the Queen City of the West, without spot or blemish.” He rode away to the war shouting, “Faugh-a-Ballaugh!”

From the start Lytle showed a troubling propensity for injury. On the march from Bulltown to Buckhannon, in western Virginia, he “came very near shooting off my toes,” as he told his Uncle Ezekial, when his pistol exploded in its holster and a ball grazed his boot. A few nights later his horse stumbled over a large tree in the dark and went down hard, with Lytle somehow managing to avoid being crushed, although Faugh-a-Ballaugh did fall on one of his legs and “came near rolling down a steep precipice.” During the advance to Bulltown, Confederate skirmishers fired dozens of shots at Lytle and his men, but with little effect. His sister Lily, who recently had married prominent local attorney Samuel Broadwell, suffered nervous prostration worrying about her brother and lost 20 pounds in two months. She professed herself “almost heart-broken” at her brother’s departure.

The “Most Unequal Contest”

Once at the front, Lytle and the 10th were not long in making a name for themselves. On September 10, 1861, while serving under fellow Cincinnatian Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, the regiment was ordered to attack a fortified Confederate position in the woods opposite Carnifex Ferry on the Gauley River. Crying “Follow, Tenth!” the white-gloved Lytle led his men across a ravine and up a steep hillside into the mouth of 12 enemy cannons. The “most unequal contest,” reported Lytle, resulted in both of the regiment’s color-bearers being shot down, and Lytle himself suffered a dangerous wound when a Minie bullet struck him in the calf of his left leg, scraping the bone and barely missing two major arteries. The same bullet, passing through Lytle, killed Faugh-a-Ballaugh, who ran ahead a few steps before dropping dead. The regiment, fighting alone for the better part of an hour, pressed the Confederates hard and won the nickname the “Bloody Tenth.” Lytle had proven his worth as a combat leader while also continuing his unfortunate habit of getting injured. His commander, Rosecrans, marked him down as a man who would fight.

The wound at Carnifex Ferry knocked Lytle out of action for the next four months, and he returned to Cincinnati to recuperate. In November 1861, the regiment arrived home on leave and immediately marched past Lytle’s mansion at Third and Broadway, cheering loudly and throwing their hats into the air while their colonel, still unable to ride a horse, took a seat in an open barouche alongside regimental pastor Father William O’Higgins and led the men on an impromptu parade through the city. The 10th’s now-tattered battle flag was proudly displayed in the window of Shillito’s department store.

Garrison and Patrol in Alabama

After a brief interlude as company commander of Camp Morton at Bardstown, Kentucky, Lytle rejoined the Army of the Ohio, now led by Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell. His hard fighting at Carnifex Ferry had won Lytle advancement to the brigade level as commander of the 17th Brigade, 3rd Division. The brigade included the 10th Ohio, 3rd Ohio, 15th Kentucky, and 42nd Indiana. Brig. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel, an old professor of Lytle’s at Cincinnati College, commanded the division. Despite his new position, Lytle was passed over for brigadier general, an omission his ever solicitous sister Lily attributed to rumors that he was drinking heavily. “It cannot pain you half as much to read this my brother as it pains me to write it,” she told him. “But when you know that promotions—respect & everything you are ambitious of awaits your abstaining from the vile poison it is incomprehensible to me why you have not the moral courage to abandon it forever.”

Lytle, who had responded to a similar entreaty from Lily two months earlier by promising to abide “happily” by her wishes, apparently did not feel the need to re-avow his dedication to abstinence. Future letters did not mention the matter, although Lytle complained to his brother-in-law Samuel Broadwell that he had been “treated like a dog from the jump” in the matter of promotion. Continuing the metaphor, he attributed his situation to “a lot of dogs at Cincinnati or Columbus or Washington [who] have tracked me like bloodhounds.” He threatened darkly to “settle my private accounts with the cowardly miscreants who have maligned me” once the war was over.

For the time being, Lytle was too busy with garrison and patrol duty in northern Alabama to worry about his political enemies. “My life has been one of constant activity and incessant unremitting toil,” he told his sisters. “Never in my life have I done so much hard work.” Operating out of Huntsville, Lytle’s brigade was responsible for safeguarding the Athens & Decatur Railroad and the bridges across the Elk River. It was arduous and unwelcome duty, particularly in an area of the South that recently had suffered the brutal touch of Cossack-style campaigning, thanks to the hard hand of Lytle’s fellow 3rd Division commander, Russian-born Colonel John Basil Turchin, born Ivan Turchinineff. Turchin’s 8th Brigade had sacked and plundered nearby Athens, Alabama, after Confederate snipers fired on them from upstairs windows in the town. To Lytle’s “great disgust,” he said, the sisters of a family friend had been “plundered of everything they had” by Turchin’s soldiers. It did not improve Lytle’s mood to learn that Turchin had been recommended, along with him and their divisional comrade, Colonel Joshua Sill, for promotion—or that both Turchin and Sill would be promoted ahead of him later that year.

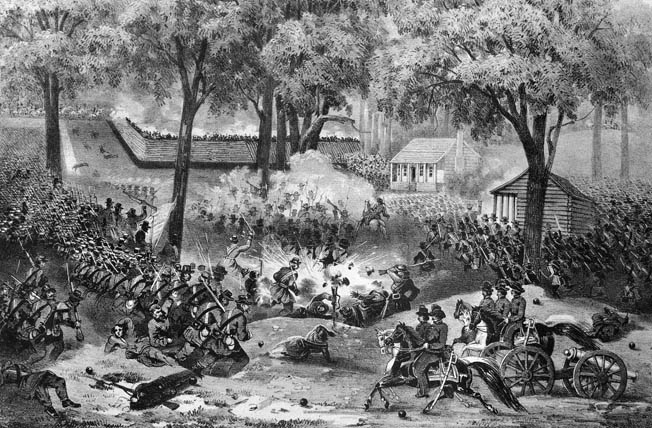

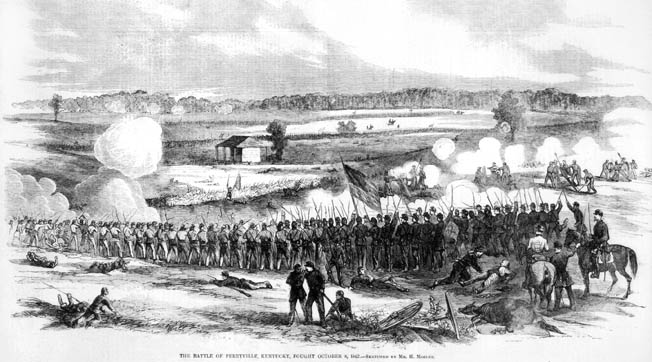

Battle of Perryville

At the end of August 1862, Lytle and the rest of the Army of the Ohio rushed northward to stave off Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s surprise invasion of Kentucky. For a time, no one knew what Bragg’s intentions were, and cities along the Ohio River from Louisville to Cincinnati fortified themselves against imminent Rebel assault. Lytle’s sisters naturally worried that their hometown would come under attack, as did their brother, but at the last minute Bragg swung away from the river and turned southeastward into rural Kentucky to link up with General Edmund Kirby Smith’s army at Bardstown. On October 8, the Union and Confederate armies blundered into each other on the outskirts of Perryville, a small hamlet nine miles southwest of Harrodsburg on the banks of the drought-stricken Chaplin River.

From the start, the Battle of Perryville was an affair—one could scarcely call it a comedy—of errors. Owing to a natural phenomenon known as “acoustic shadow,” Buell could not hear the roar of cannons three miles away, and his second in command, Maj. Gen. Charles Gilbert, blithely assured him “that his children were all quiet and by sunset he would have them all in bed, nicely tucked up.” Meanwhile, Lytle’s brigade, in Brig. Gen. Lovell Rousseau’s division on the Union left, was being roughly handled by successive waves of Confederate infantry led by Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s redoubtable division.

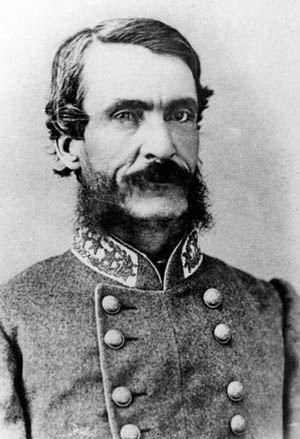

Attempting to rally his men on the heights overlooking Doctor’s Creek, a tributary of the Chaplin River, Lytle was struck behind the ear by a piece of Rebel shrapnel that exited his cheek and knocked him to the ground. Left for dead along with 265 of his 500 men, he was found sitting dazedly on a rock, still holding his sword, by Confederate Captain W.T. Blakemore, an adjutant for Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson. Blakemore asked Lytle if he needed help; Lytle responded “that those on the field needed more immediate attention.” He offered Blakemore his sword, but the captain told him suavely that “one who could command such men should never suffer such indignity.” Instead, he escorted Lytle to Johnson’s tent, where the fellow Ohioan took one look at Lytle’s blood-smeared face and vacant expression and sent him back to the brigade surgeon for emergency aid.

Lytle’s Parole

The next day, Lytle was taken to Harrodsburg and paroled. He returned to Cincinnati to await formal exchange, and on December 1 testified at a court of inquiry looking into Buell’s less than stellar handling of the army at Perryville. Falling back on his legal training, Lytle declined to testify directly about anything he had seen while in Confederate hands, quoting a provision in his parole that enjoined him “not to reveal anything that I might have discovered within the line of the enemy.”

Lytle’s testimony, or lack thereof, did not help Buell, a fellow Democrat, who was removed from command by Republican President Lincoln and replaced by Lytle’s old commander in western Virginia, William Rosecrans. Luckily for Lytle, he was too late to rejoin the army for the gruesome Battle of Stones River, fought near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on the last day of December 1862. There, Rosecrans won a narrow but decisive victory, holding Nashville for the Union and sending Bragg’s Confederates stumbling southward into winter camp around Tullahoma. Among the thousands of Union casualties during the two-day battle was recently promoted Brig. Gen. Joshua Sill, who was killed leading the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, XX Corps of the Army of the Cumberland—the new name for the main Union army in the western theater of the war. In a bit of irony that probably was not lost on Lytle, he inherited Sill’s command under Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, yet another Ohioan (from Somerset).

“Such is War”

Rejoining the army at Murfreesboro in February 1863, Lytle took advantage of the lull in fighting to pay a courtesy call on the Tennessee branch of his family. He had made the acquaintance of David Lytle the previous year while stationed near Murfreesboro, and he gladly accepted an invitation to stay with the family until his army promotion and living quarters were finalized—the weather, as he told Lily, “has been detestable and the mud is knee deep.” David Lytle died that winter, but Will continued living with the family. He apparently developed a serious affection for the widow, Sophia Dashiell Lytle, whom he described as “brilliantly educated—a fine Latin & Greek scholar & a very charming lady.” He repeatedly urged his sisters to send Sophia food, clothing, and other hard to come by items in Union-occupied Tennessee. At the same time, he reaffirmed his attachment to his cousin Sed, sending word through his sisters “that I will never forget her, and if I survive the wars hope to meet her again.” Sophia Lytle subsequently transferred her affections to Captain Carter Harrison, grandson of President William Henry Harrison and brother of future president Benjamin Harrison.

There was little time, at any rate, for romance. The hard-charging Sheridan put Lytle to work marching, picketing, and overseeing bridge repairs for the division. Lytle’s brigade consisted entirely of northwestern regiments: the 36th and 88th Illinois, 21st Michigan, and 24th Wisconsin. They were “said to be full of fight,” Lytle reported proudly, and they would soon have the opportunity to prove their reputation. That June, after months of hectoring from an increasingly exasperated War Department, Rosecrans commenced his long-awaited drive toward Chattanooga, on the Tennessee-Georgia border, whose confluence of railroads and rivers gave it a strategic importance far beyond its ramshackle appearance.

Lytle’s brigade, spearheading the advance, was in the lead when the army reached the hamlet of Cowan, Tennessee, in early July. There, wrote Lytle, one of his sharpshooters accidentally shot and killed a young boy dressed in gray who ill-advisedly ran toward them in the rain. The youth was attempting to put back a fence rail, and Lytle’s men took him for a sniper. It later transpired that the boy’s family was pro-Union, and his teary-eyed sister leaned out an upstairs window as they passed and cried: “Hurrah for the Union, but oh you have killed our dear little Freddy.” “Such is war,” Lytle sighed sympathetically.

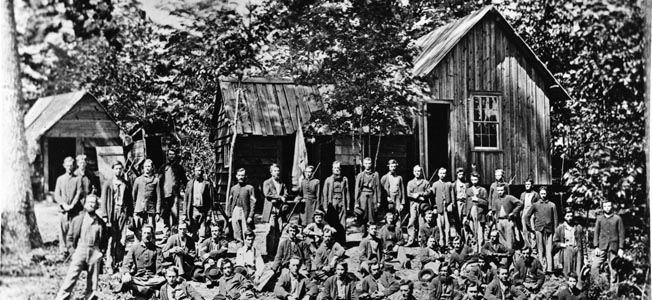

The Maltese Cross

In one of the smoothest strategic feats of the war, Rosecrans feinted Bragg out of Middle Tennessee with a series of brilliant flanking maneuvers. At Bridgeport, Alabama, 25 miles southwest of Chattanooga, the army stopped to replenish supplies before a final push toward Chattanooga. Lytle’s brigade was tasked with rebuilding a railroad bridge across the Tennessee River that the Confederates had partially burned. During a break from his bridge-building duties, Lytle was invited to a special encampment of his old 10th Ohio Regiment, at which Colonel William W. Ward presented him with a jewel-encrusted Maltese cross, a belated parting gift from the regiment.

Never at a loss for words, Lytle responded with a graceful speech thanking his old friends for remembering him and promising, in turn, to remember them for the rest of his life. “It may not be for all of us there today to listen to the chants that greet the victor, nor to hear the brazen bells ringing out the new nuptials of the states,” Lytle said. “But those who do survive can tell how their old comrades died with their harness on, in the great war for Union and liberty.” The speech was reprinted in the Cincinnati Commercial, where it received “quite a run at home,” Lytle bragged. His commanding general was less impressed. Rosecrans needled Lytle, in the presence of a number of other officers, “Lytle, was your father a better orator than you?” Lytle, understandably, was not amused.

“The River of Death”

The time for speeches quickly passed. In early September, the Army of the Cumberland occupied Chattanooga without a shot, the Confederates falling back into northwest Georgia. Rosecrans would have been well advised to remain in Chattanooga and wait for reinforcements before pursuing Bragg’s army into the heavy woods beyond. But stung by the repeated criticism of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and the implied displeasure of President Lincoln, he ignored advice to do just that and instead pushed ahead, convinced that Bragg’s army was retreating in disarray. Dividing his own army into three wings, Rosecrans stalked after Bragg, in the process dangerously extending his own lines and isolating his three corps in the mountainous gaps below Chattanooga. In the meantime, Bragg had secretly consolidated his army in the deep woods to the east of the mountain passes. He intended to destroy the Union army at his leisure, one corps at a time. Had it not been for a bungled preliminary attack at McLemore’s Cove, Bragg’s plan might well have worked. As it was, Rosecrans belatedly realized the deadly peril he was in and hastily ordered his units to concentrate in the vicinity of Crawfish Springs, a puddle-sized hamlet 12 miles south of Chattanooga.

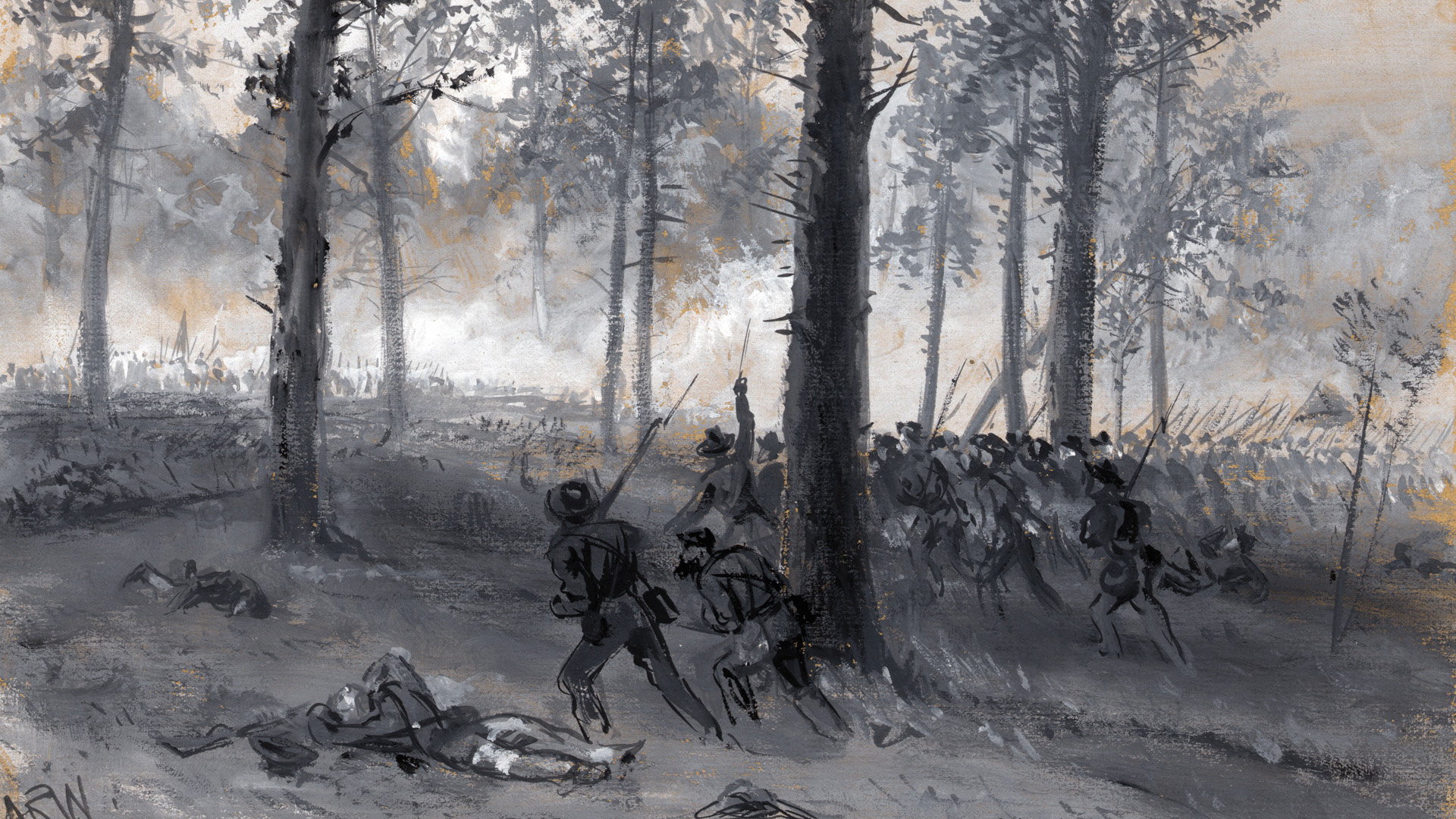

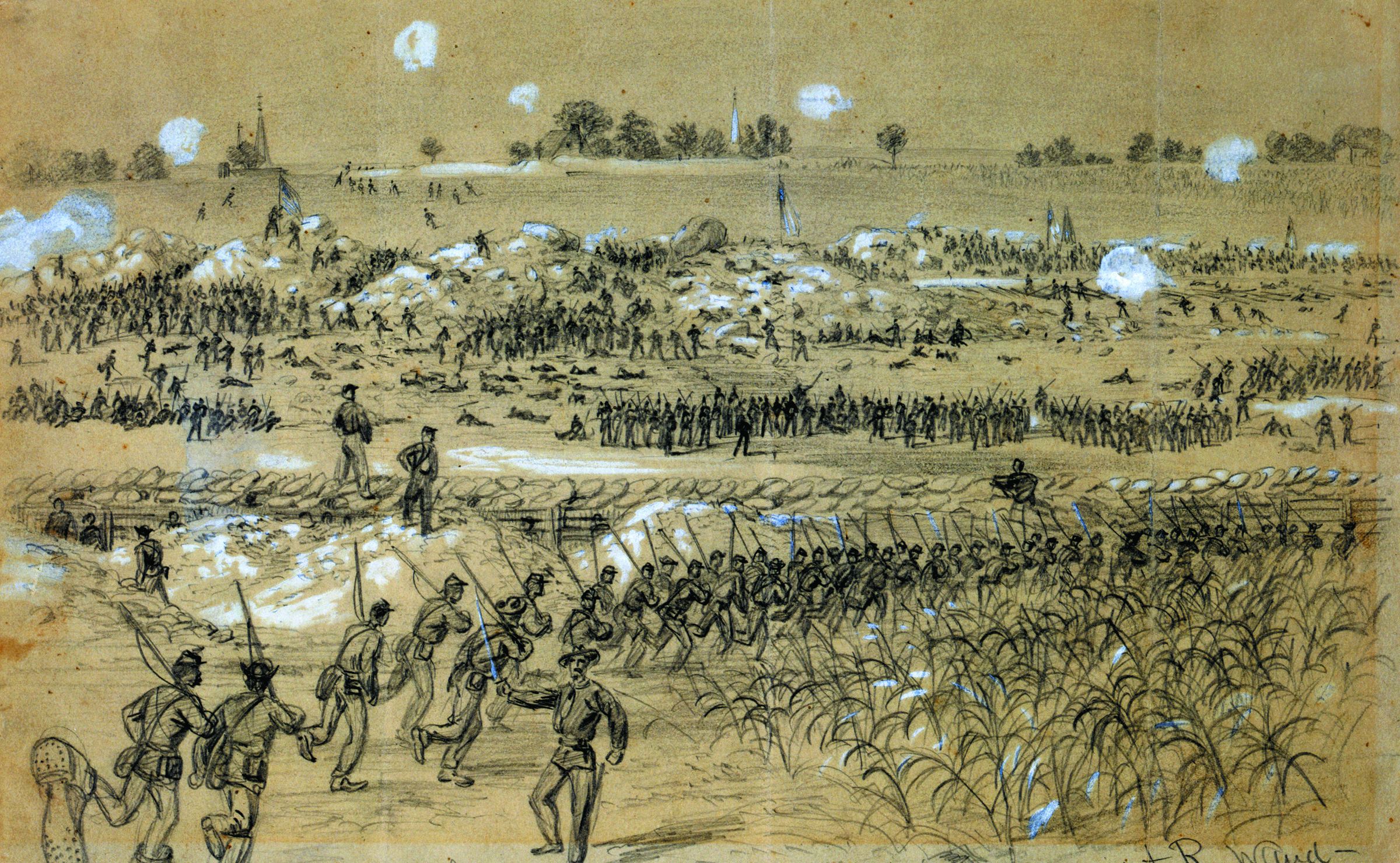

On September 19, the Battle of Chickamauga exploded. As Rosecrans had guessed, Bragg intended to turn the Union left and block the road back to Chattanooga. With unparalleled savagery, the two armies collided in the vine-covered thickets around Chickamauga Creek. (“Chickamauga” is an old Indian word romantically mistranslated as “the River of Death.” It actually means “bad water,” commemorating a long-ago smallpox epidemic.) The fighting raged until long after dark, “one solid, unbroken wave of awe-inspiring sound,” a participant recalled, “as if all the fires of earth and hell had been turned loose in one mighty effort to destroy each other.” The Union line, although forced back in places, somehow managed to hold together. The next day, each side realized, would prove decisive.

Lytle’s brigade, left behind to safeguard the army’s right at Lee and Gordon’s Mill astride the La Fayette Road below Chickamauga, missed the first day of combat altogether. Summoned hastily to reunite with its besieged comrades, the brigade pushed on to the battlefield, arriving about 2 am and bivouacking on a hillside near Rosecrans’ headquarters, the cabin of a backwoods widow named Eliza Glenn. The night was unseasonably cold, and campfires were prohibited. Lytle’s men slept on the frosty ground, their muskets beside them—those who could actually sleep with the screams of hundreds of wounded and dying men cascading around them in the dark.

Lytle was untypically gloomy. Besides the dangerous position of the army and the prospect of even more desperate fighting the next day, he was suffering from a heavy cold that made it hard for him to breathe—sleep was out of the question. Calling his aide, Cincinnati-born Lieutenant Alfred Pirtle, to his side, Lytle put his arm around him and said quietly, “My boy, do you know we are going to fight two to one today?” He explained that Bragg’s Confederates had been reinforced by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s redoubtable I Corps from the Army of Northern Virginia. Even then, Longstreet’s men were creeping stealthily through the woods less than two miles away from Lytle’s camp in preparation for one of the most startling breakthroughs of the entire war. An unread letter from Lily was stuffed into Lytle’s coat pocket. His orderly, Joseph Guthrie, the son of Cincinnati lawyer James Guthrie, urged the general to keep out of the fight the next day. “No, Guthrie, I never shrink from my duty,” said Lytle, “but if I fall I want you to carry me off the field—and take care of my poor horse.” The long night dragged on.

Lytle Hill

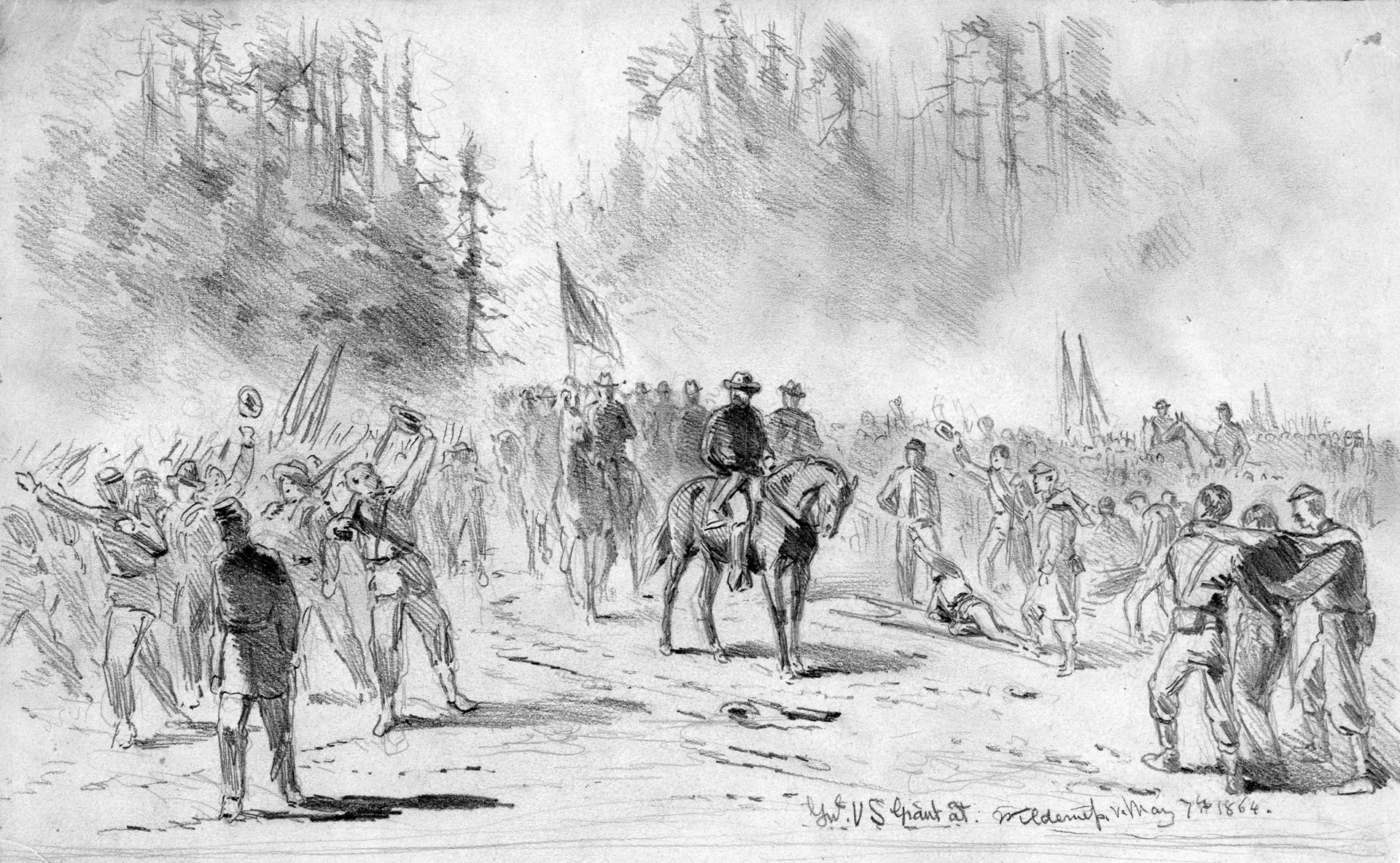

The next morning the battle resumed with a vengeance, the Confederates mounting a series of rolling attacks on the Union line from north to south. Rosecrans, frantic and exhausted, issued a burst of panicky orders to reinforce the Union left and began shifting troops in that direction. Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s division, to the immediate left of Lytle’s brigade, had just pulled out of line to obey Rosecrans’ latest directive when, more or less by coincidence, Longstreet launched an attack on the just vacated position. Screaming the Rebel yell at the top of their lungs, the first of 11,000 battle-hardened Confederates surged through the gap, instantly cutting the Union army in two and threatening to annihilate all opposition. Lytle was at Union headquarters talking to his divisional commander, Phil Sheridan, when the breakthrough occurred. Sheridan immediately ordered him to move his men into line from their sheltered position on a dirt road behind the hill below the Widow Glenn’s. Lytle obeyed at once, calling to his lead regiment, the 88th Illinois, “Forward into line!” He pulled on a pair of dark kid gloves and murmured, perhaps to himself, “If I must die, I will die as a gentleman.”

Already, as Lytle brought his troops up the slope of what would become known as Lytle Hill, the far side of the heavily forested crest was boiling with Confederates. Brig. Gen. Zacharias Deas’ Alabama brigade was in the lead, firing devastating point-blank volleys into the backs of retreating Union soldiers and stopping to reload a few hundred feet from Lytle’s hastily improvised position. Pirtle, riding back to join Lytle after carrying a message to a nearby artillery battery, saw the general exhorting his men with emphatic gestures of his saber. “Boys,” said Lytle, “if we whip them today we will all eat our Christmas dinner at home.” Distractedly, he twisted his mustache with the fingers of his left hand.

“Brave Boys, Brave Boys”

Lytle had no way of knowing it, but the Rebels coming ominously toward him were commanded by an old friend, Tennessee-born Brig. Gen. Patton Anderson. As Democrats, the two had shared a common political bond, and they had also served together in Mexico. A few months before the Civil War, they had last seen each other in Charleston, South Carolina, and Anderson recalled that when they parted, “they promised that nothing should ever interfere with their friendship, and if either should ever be in trouble the other was to assist him in every way practicable.” There was nothing Anderson could do for Lytle now; his Mississippi troops were firing as quickly as they could at anything blue, and the mounted Lytle, silhouetted against the green-brown hillside, was too easy a target to miss.

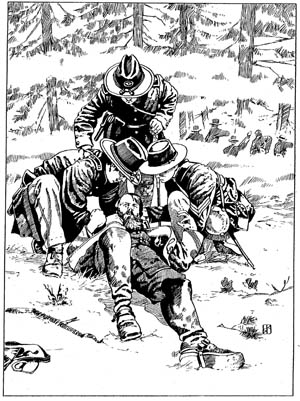

Pirtle, who had rejoined Lytle, leaned over to hear what the general was saying above the din of battle. “I bend to catch what he is saying,” Pirtle recalled years later, the battle still a present-tense memory. “He calmly says with a firm voice ‘Pirtle, I am hit.’ For an instant I cannot speak; my heart almost ceases to beat, but I say ‘Are you hit hard, General?’ ‘In the spine—if I have to leave the field you stay here and see that all goes right.’ ‘I will, General.’” A moment later, Lytle sent Pirtle dashing off to bring up a lagging regiment. Another aide, Captain Howard Green of the 24th Wisconsin, moved to his side. Lytle turned to say something to Green. At that instant, a bullet struck Lytle squarely in the face, entering at the left corner of his mouth and exiting through his right temple. He reeled in the saddle; Green caught him as he fell. A passing sergeant of the 24th Wisconsin, Thomas J. Ford, heard Lytle gasp his last words: “Brave boys, brave boys.”

Green lowered Lytle to the ground. The stricken general tried to say something else, but his mouth was full of blood. Bullets were whizzing everywhere. Colonel Thomas Harrison of the 39th Indiana Mounted Infantry rode up, dismounted, and attempted to help Green and a couple of orderlies carry Lytle away, but an exploding shell wounded one of the orderlies. Green was fumbling his hold when Lytle gave a sudden convulsive tug of Green’s knees and relaxed into death. Harrison remounted his horse and rode away; Green ran for the opposite side of the hill. Confederates swarmed onto the crest, yelling with exultation. The ever-loyal Pirtle was headed back up the other side of the hill when a riderless horse careened past him—it was Lytle’s. He turned and ran the other way, tears blinding his steps.

Final Resting Place For William Lytle

While the wave of battle swept northward from later-named Lytle Hill and the remnants of the Union army came to rest a mile away on another ravine-riddled prominence called Snodgrass Hill, a number of Confederate officers who had known Lytle before the war stopped to pay their respects to the fallen general. First to arrive was Anderson, who knelt beside his old friend and carefully removed a ring, several photographs, and a lock of hair, intending to send them through the lines to Lytle’s family. Anderson posted an honor guard around the body and ran to catch up to his brigade. Major William Owen, a friend of Lytle’s from childhood, arrived next. He was looking down at Lytle when Brig. Gen. William Preston rode up and asked, “What have you here?” “General Lytle of Cincinnati,” said Owen. “Ah! General Lytle, the son of my old friend, Bob Lytle,” said Preston, immediately dismounting to pay his respects. “I am sorry it is so.”

Confederate surgeon E.W. Thomasson, who had served with Lytle in the Mexican War, came onto the scene a few minutes later. Lytle, he said, was “as good a man as ever lived, even if he did have on Yankee clothes.” Thomasson commandeered an ambulance to take Lytle’s body to the rear. A dying Confederate captain, James Deas Nott of the 22nd Alabama—the same regiment that had killed Lytle—was asked if he minded sharing his ambulance with the slain Union general. Nott had no objection. By the time the ambulance reached a makeshift field hospital behind the lines, both men were dead. Later that night they were buried side by side in hastily dug graves.

A few days later, Lytle’s body was disinterred and returned through the lines under a flag of truce by members of his first regiment, the 10th Ohio. After a brief memorial service in camp, Lytle’s flag-draped casket was shipped back to Cincinnati by boat. On October 22, after lying in state for one day in the city courthouse, where his former fiancée Sed Doremus kept an all-night vigil beside his casket, Lytle was reburied at Spring Grove Cemetery. The largest crowd ever to attend such a local event watched as the funeral procession wound its way to the cemetery from Christ Episcopal Church. Lytle’s old orderly, Joseph Guthrie, led the general’s riderless horse, with Lytle’s boots reversed in the stirrups. Future president James A. Garfield was one of the pallbearers. The procession dispersed at Central and Freeman Avenues, and a carriage containing Lytle’s immediate family—sisters Josephine and Lily and their husbands—said a last goodbye in the early twilight. It rained on their brother’s newly turned grave—a symbolic touch the poet-general would have approved.

Originally Published March 30, 2017

What an absolutely wasteful and unnecessary war.

It was politically inevitable. By that measure it was necessary though war is wasteful.