By Glenn Barnett

The date of November 10, 1942, is still vivid in the mind of Albert Wayne Boam. That was the day that he enlisted in the Army Air Corps, hoping to become a fighter pilot. He never imagined that he would go off to war, only to become a prisoner.

Manhattan born and bred, Albert grew up on the Upper East Side in a few different apartments. “During that time apartments were reasonably priced,” he recalled. He attended Stuyvesant High School, whose alumni also included actors Jimmy Cagney and Robert Alda, father of Alan Alda.

He was activated for duty in early March 1943 and took a train from his native Manhattan to Nashville, Tennessee, and basic training.The train to Nashville made a stop in Louisville, Kentucky, where the young recruits could get a bite to eat. The most convenient place near the station was the Blue Boar Café. Albert and his mates, full of New York bravado, kidded around with their waitress until, aggravated, she told them to kiss her behind. “It was the first time I had heard a woman swear,” he said.

Arriving at Nashville, recent rains compelled the new men to hike through the red mud of Tennessee to their barracks. The red mud was an unusual sight for the young Yankees. The barracks featured coal-burning stoves that were supplied with bituminous coal, which soon caused respiratory problems among the recruits. The ensuing coughing fits became known as the “Tennessee Hack.”

While in Nashville, the men were given aptitude tests for the different positions on a bomber; Albert passed the tests for pilot, bombardier, and navigator. His dreams of becoming a fighter pilot evaporated when he was assigned to take navigator training at Selman Field outside Monroe, Louisiana, where he was instructed in meteorology and other subjects. He flew practice missions in a twin-engine plane learning to use a drift meter.

From there Albert was sent to gunnery school in Florida for six weeks and learned to shoot .45-caliber pistols and then to load and fire .50-caliber machine guns, which he had to strip and reassemble while blindfolded. He also recalled another difficult training maneuver: “One of our drills was to take a shotgun in the back of a moving bus and shoot skeet, which were flung at different angles and altitudes.”

Boam next flew in the rear seat of an AT-6 Texan aircraft for advanced training in air-to-air gunnery; the trainees fired on targets being pulled by another plane. Part of his training was to hold steady when the tow pilot made sudden maneuvers. In one contest he won third place among all gunners on the base.

In December 1943, he got his wings and the gold bars of a second lieutenant. The newly minted navigators were given a 10-day leave for Christmas and told to report to Casper Army Air Field at Casper, Wyoming, where, after the heat and humidity of Louisiana and Florida, it was freezing cold that winter. Albert was assigned to the 489th Bombardment Group (Heavy), commanded by Brig. Gen. Ezekiel W. Napier, for further training. He was teamed with a crew of a Consolidated B-24D Liberator heavy bomber. One of his crewmates was pilot Sal Mauriello, a cousin of heavyweight boxer Tami Mauriello, who, in 1946, would have a title fight with Joe Louis.

After a few weeks, all the navigators were transferred and reassigned to different crews at Wendover Army Air Field in Wendover, Utah. At the time, Wendover was the military’s largest bombing and gunnery range. Flying in B-24s, the navigators-in-training were given navigating exercises. They had to triangulate their positions on long flights that could take them as far as Montana in the north and Las Vegas in the south.

The only perk of this assignment in such a desolate place was that Wendover was located on Utah’s border with Nevada. Boam and several other men were housed in the uniquely situated State Line Hotel; one half of the hotel was in Utah and the other half was in Nevada. As Utah was a “dry” state and Nevada had more permissive laws, most of the men spent their free time on the Nevada side of the hotel.

The nearest big city was Salt Lake City. Men on leave would take a bus on an almost straight line past the Bonneville Salt Flats to get there. At that time there were no posted speed limits, and the bus raced through the desert to its destination.

By the spring of 1944, the assembly-line technique for producing airplanes was in full swing, and a flood of B-24s built at the Ford Motor Company facility in Willow Run, Michigan, rolled off the line. The newly trained crews found the planes easy to fly.

When the 489th had completed its unit formation and combat training, it received orders to depart Wendover on April 3, 1944. Albert and the newly formed squadron were ordered to Kansas City and then on to Morrison Field, the former civilian airport for West Palm Beach, Florida. The new arrivals, like soldiers everywhere, speculated about where they would be assigned. Many thought they would go to Burma and India to fight the Japanese, but they soon learned that they would be assigned to the Eighth Air Force based in Great Britain.

To reach England, most air crews flew via the northern route, which took them through Newfoundland; Albert and his squadron flew via the southern route. Their first stop was in Puerto Rico. The airmen were delighted to find that this island stop featured 10-cent frozen daiquiris. The enterprising crews filled their empty bomb bays with cheap rum and then flew on to Trinidad and Georgetown in Guyana. From there they headed to Fortaleza, Brazil.

Brazil had quantities of that most important of commodities—nylon stockings—which, due to wartime rationing of silk, were not available in the States. Albert bought several pair and shipped them to his sisters, who were delighted. That was not his most vivid memory of the country, however. “What I remember most about Brazil was the flying cockroaches.”

The next stop was Natal, the easternmost city in Brazil and the most convenient spot for the hop across the Atlantic to Africa. The flyboys made the jump to Dakar in French West Africa (now Senegal), which at the time had recently passed from Vichy to Free French control. “It was the only time that I used celestial navigation, which I had learned in advanced training,” Albert said. From there the B-24s flew on to Marrakesh, Morocco, where Albert remembered catching a ride on a donkey-powered taxi.

After Morocco, they flew directly to Great Britain. While passing Portugal, however, an unidentified plane resembling a German fighter was seen in the distance; the B-24 pilot ducked into nearby clouds to avoid confrontation. Once past Portugal, the rest of the flight was uneventful until almost the end. They were assigned to land at RAF Halesworth, located between Norwich and Ipswich in East Anglia, but so many airfields now dotted the English countryside that they were lost among all the new military air bases. They ended up landing in Wales, hundreds of miles to the southwest.

Albert remembered, “The local people were most hospitable and friendly.” Each of the officers was assigned a “batman” who, in the British military, was a soldier who was assigned as a man-servant to a commissioned officer. Albert took advantage of his batman long enough to get his boots polished before his plane flew on to RAF Halesworth, the 489th’s new home. The 56th Fighter Group was also stationed there. The 489th had four squadrons—the 844th, 845th, 846th, and 847th; Albert was assigned to the 846th Bombardment Squadron.

While at Halesworth, the squadron flew several practice missions over the North Sea. Just before their first combat mission, two of the Liberators, trying to avoid a pair of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers headed straight for them out of the clouds, collided with each other, causing both ships to crash with resulting fatalities. It was an unnerving experience for the young crews of the other planes.

When not flying a combat mission, crew members spent their spare time lounging around their field, writing letters home, playing cards, going to pubs and dances in nearby towns (the closest to RAF Halesworth were Norwich and Ipswich), going on pass to London, or—most importantly—catching up on sleep.

A navigator in another bomb group (the 455th) described life in the Eighth Air Force: “We dreaded every mission, but we knew that we had to fly the missions in order to get home. All of us flew in terror. We prayed a lot. Some of us drank a lot. Some of us smoked a lot. To escape the war, we walked or biked out on the English countryside any chance we had.

“Our crew was our family. We did just about everything together and took care of one another, no matter what. The English girls we met, we held them tight. They were the angels in our world of sudden fiery death. Some of us barely held on to our sanity. The flight surgeons gave us the right medicines to keep us functioning the same way our mechanics kept our bombers flying. One of the crew broke down under the strain, and we couldn’t help but envy him as he was pulled out of combat…

“Many years later we would learn that, statistically, there was no more dangerous place to be in World War II than in a bomber over Germany. The medals we received were not for heroism. They were for having survived the danger of collision with our own planes, of being wounded by a piece of flak shrapnel, of being blown to kingdom come by a direct hit, of going down because of a malfunctioning airplane, of being attacked by German fighters, of crashing into the sea—of injury or death in a thousand ways.”

The 489th flew its first combat mission on May 30, 1944, just a week before Operation Overlord, the Normandy invasion. At the time, crews had to survive a minimum of 25 missions before they could return home.

The wake-up call came at 4 am, with the briefing taking place after breakfast. The targets for the 489th Group’s 135 B-24s were aviation depots and the Wilde Sau fighter unit at Oldenburg in Lower Saxony, west of Bremen. As the 489th Group flew over the Dutch coast, German flak came up to meet them. It was the group’s first introduction to the deadly German antiaircraft fire.

A crew didn’t need to be shot down to be lost. On the Oldenburg mission, another crew flying its first combat mission had made the mistake of not fueling the plane properly, leaving it short of fuel for a round trip. As a result, it ran out of gas before it could make it home and had to ditch in the North Sea. Its surviving crewmen were fished out of the water by the Germans and taken prisoner.

Albert remembered another man in the squadron named Jack “Joe” Garber, who had been the U.S. national handball champion in 1938 and 1942. On the group’s second mission, Garber’s flak helmet became uncomfortable so he removed it to adjust it. At that moment a chunk of flak hit and killed him.

Albert’s plane was named Little Eva by its engineer. (Another B-24 Little Eva crashed off the coast of Australia in December 1942.) Little Eva’s second mission, on May 31, 1944, was to hit V-1 “buzz bomb” launch sites in the Pas de Calais area of France. Flying between 7,000 and 8,000 feet, the first pass over the target was at an awkward angle, and most of the planes failed to drop their bombs. The flight commander was not satisfied and ordered a second pass over target, never a good idea.

Now the Germans knew they were coming, plus their range and altitude. Flak was accurate, and Little Eva returned to base riddled with 186 holes from ground fire. The hydraulic system had been pierced, and there were no brakes. “One of the holes was directly beneath where I was sitting,” Albert recalled. “I’m still amazed that it didn’t hit me.”

One of the waist gunners was hit in the arm; he was badly wounded and would not fly in combat again. A couple of planes were shot down, and most of the planes received damage. “That is the day I started smoking,” Albert recalled.

To make matters worse, while flying back to base over the Thames River Estuary, Little Eva flew below 10,000 feet and received antiaircraft fire from the British. It was a rule that they were not to fly below 10,000 feet near London so as not to be mistaken for German bombers. Either the pilot didn’t remember or the plane was too badly shot up to hold altitude.

Then things got even worse. The lights at Halesworth went out as Little Eva approached, and the planes circled a few times before being diverted to RAF Metfield, about 18 miles south of Norwich. Since the plane landed with no brakes, the pilot performed a ground loop to bring it to a stop.

The 489th took part in several more raids prior to and after the Normandy invasion. One in particular stands out in the annals of the group’s history: June 5, 1944. On that day, Lt. Col. Leon R. “Bob” Vance was commanding the group in a diversionary raid on German coastal defenses at Wimereux, France. Vance was positioned behind the pilot and co-pilot of a B-24 carrying a ground radar set. During the initial run over the target, the lead plane’s bombs failed to jettision, so a second run was ordered. A flak burst killed the pilot of the plane in which Vance was riding and badly wounded Vance, nearly severing his right foot.

When the co-pilot took charge of the plane, Vance assisted him in bringing it under control. Returning to England, Vance, now piloting the B-24, ordered the crew to bail out over the English Channel, as it was too badly damaged to land safely. Erroneously thinking that the plane’s radio operator was still on board, Vance made a successful water landing to save the man’s life, but an explosion occurred that blew Vance free of the cockpit. He was picked up by a British air-sea rescue boat, but his foot had to be amputated.

As Vance was flown back to the United States on July 26 for further medical treatment, the C-54 Skymaster on which he and other wounded Americans were flying disappeared over the North Atlantic. Vance was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor––the only Medal of Honor awarded to a B-24 crewman for an action flown from England. In 1949, Enid Air Force Base in his hometown of Enid, Oklahoma, was renamed Vance Air Force Base in his honor.

On D-Day, Little Eva set out to bomb St. Lô, France. Flying under the clouds, Albert was stunned by the number of ships involved in the cross-Channel invasion. “It looked like you could walk from one end of the Channel to the other,” he remembered.

On this trip, the pathfinder aircraft that was to lead the way and designate the target failed to appear. The planes assigned to bomb St. Lô found visibility limited by clouds and aborted their mission.

After D-Day, the turnaround in missions was rapid; it seemed to Albert that Little Eva was flying a mission every other day. He flew two raids against Munich (July 11 and 12, 1944). Every available plane in the Eighth Air Force took part in these famous “thousand plane” raids.

Several of the missions also targeted marshaling yards where rail traffic was concentrated. At least one of his missions was against Villacoublay Air Base, eight miles southwest of Paris, where the Luftwaffe maintained a fighter base and some aircraft manufacturing facilities.

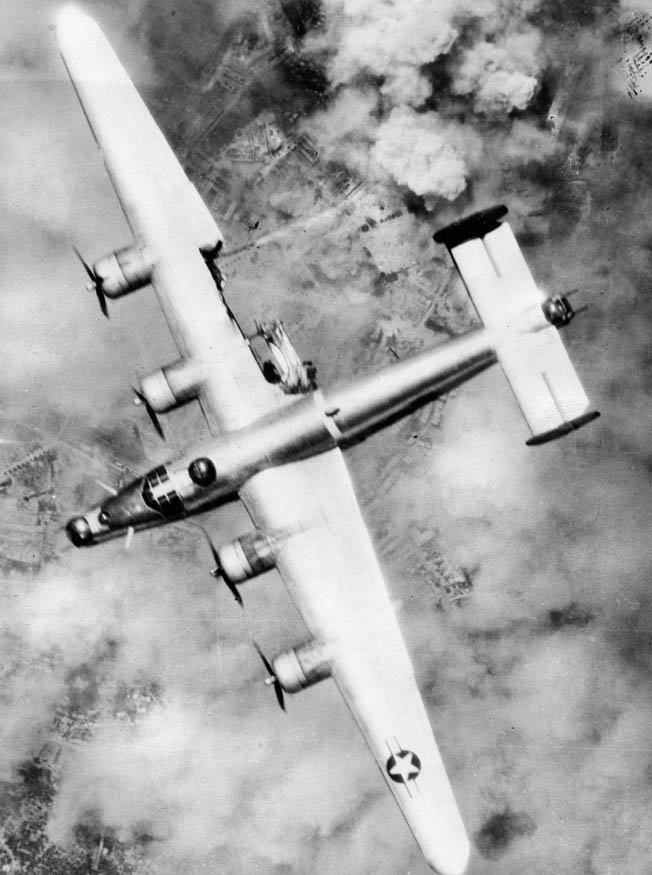

B-24s dropped over 450,000 tons of bombs on Europe during World War II.

The group’s July 31 mission was directed against the I.G. Farben chemical plants at Ludwigshafen-am-Rhein, across the river from Mannheim, Germany. Little Eva and her crew had logged 30 missions, and the July 31 mission would be their last—but not the way they had hoped.

Little Eva was the second plane in formation following the pathfinder aircraft, which led the way to verify the target.

As the squadron tagged after the pathfinder, Albert began to notice that they were off course. He radioed his pilot this information, but it was not transmitted to the lead plane. Their approach was erroneously leading them over the outskirts of Saarbrücken and in range of the city’s antiaircraft defenses. Soon flak rose into the sky and hit Little Eva’s control surfaces on the right wing. Had the flak hit a few inches to one side it would have ignited the fuel tank with disastrous results.

Little Eva peeled out of formation to the right and flew erratically, losing speed and altitude. The pilot knew that they could not hope to make it back to England. As he struggled for control of the aircraft, the pilot desperately hoped that they could reach Switzerland, where they would be safe. But Little Eva was becoming more difficult to control and had slowed almost to stall speed.

The pilot gave the order to bail out. Starting at about 8,000 feet, the crew leaped out one by one. Albert left through the nose-wheel door, chipping a tooth in the process. “I opened my parachute right away,” he said. For more than 70 years he has believed that he opened it too soon. Little Eva hurtled to the ground and crashed. William Bunton, the co-pilot, and Albert, bleeding from the mouth, landed in the same area. They huddled together trying to figure out what to do next.

They had landed near a police station at Hagenau in German-controlled Alsace-Lorraine. The local police chief and his men captured them. He swore at them, calling them “American terror gangsters.” In his anger, he took a few swings at the co-pilot, who was a much bigger man. The “gangsters” spent two nights in the local jail.

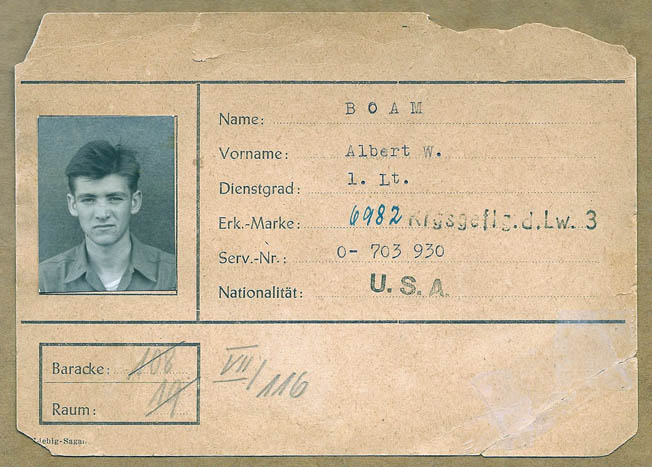

On the third day, a truck bearing the markings of the Luftwaffe arrived to pick them up. The two men were taken to the Dulag Luft (prison camp for enemy aviators) in Oberursel near Frankfurt. Opened in 1939, this was the largest transit camp in Germany for captured Allied fliers. At Dulag Luft, POWs were sorted out, interrogated, and shipped on to POW camps.

Upon arrival, Albert and his co-pilot were locked up in solitary confinement, given little to eat or drink, and slept on a wooden palette with a little pile of straw. After three days, they were taken under guard to the office of an English-speaking Luftwaffe officer. He had done his homework. “He seemed to know a lot about me, where I had trained, and my squadron number,” recalled Albert. The young navigator was asked a series of questions, the answers to some of which, he was sure, the German already knew. But Albert’s answer to all the officer’s questions was “name, rank, and serial number.”

After five days at Dulag Luft, they were shipped by rail to Sagan, Lower Silesia, and a Luftwaffe prison camp named Stalag Luft III. This was the famous prison camp that was the site of “the Great Escape.” That event and the brutal reprisals that followed occurred in March 1944—before Albert arrived.

In the camp, he was ultimately reunited with the other officers of his crew, pilot 1st Lt. Arthur P. Bertanzetti and bombardier Tom Day. They had hidden and evaded capture for several days. All the enlisted

men were sent to Stalag 17 in Austria. Their treatment would be much worse than that of the officers.

At Stalag Luft III, they learned that Americans were being shot down in such numbers that there was no room for the new arrivals in the west camp that was set aside for U.S. air crews. So Albert was placed in the north compound which housed RAF flyers, including those from Canada and Poland. Some of these men had been imprisoned there since 1939 and 1940.

“I was really impressed with their organization,” Boam said. “They had a well-stocked library, a record collection and a phonograph to play them. They organized lectures, put on plays, with men in drag playing the women’s parts. They printed their own camp newspaper and clandestinely hid a short wave radio from which they gathered and verbally disseminated the BBC news of the day. The radio was given the code name ‘tobacco’ to help hide its existence. For entertainment at night I most often played cards.”

For exercise there was an oval area around the camp inside the barbed wire, where men took their daily constitutionals (as the British called it), and touch football and softball games were organized. Albert remembered, “One day an Me-109 buzzed the compound, perhaps paying respect to his fellow airmen. One of the prisoners threw a softball at the passing plane. Fortunately for us all, he missed. On another occasion, an Me-262 German jet buzzed the compound. At first, there was awe at the plane with no propeller and the rumbling sound, but being fly boys we soon figured out what it was and what it meant”—that Nazi Germany had jet-powered planes that might tip the scales in Hitler’s favor.

For food at the camp there was a dwindling amount supplied by the Luftwaffe—often no more than insect-infested cabbage soup. “We had to drain off the bugs before

eating it,” Boam recalled. From time to time they received a baked potato and sometimes a hard piece of dark brown bread. The bulk of their diet came from Red Cross food parcels.

Each parcel contained several items. “I remember tinned corned beef, powdered milk in a can, a chocolate bar, margarine, and a pack of cigarettes,” said Albert. The growing number of Allied airmen in the camps limited their portions. The men were placed on half rations, and 15 parcels were doled out to 30 men every two weeks.

Letters from home had to be written on special forms. They were heavily censored, with many blacked-out words and phrases, and they always seemed to be delivered two months late.

Early on, the camp had devised a monetary system based on food, soap, cigarettes, and other supplies. Nonsmokers could barter their cigarettes (or “fags” as the British called them) for chocolate or other goods received from the outside. If an item became scarce, it rose in value. If it became more readily available, the value fell based on the trading that was done each day. “The system was like an informal stock exchange,” Albert said, and it worked. Though he smoked, he was more than glad to trade his cigarettes for other items.

The officers of Little Eva settled into camp life until January 1945. On the 12th, the Russians began their long-awaited and overpowering offensive all along Germany’s Eastern Front. As the fighting moved closer to Stalag Luft III, the prisoners were moved westward. After the war it was learned that Hitler wanted all the POWs to be killed in the dying days of the Third Reich. The army thought better of it, and even though the Nazi regime was crumbling it was still considered important to hold on to Allied POWs as bargaining chips in any future negotiations.

By January 27, the Russians were within 16 miles of camp. “The guards announced that the prisoners had two or three hours to gather our belongings and all the Red Cross parcels we could carry,” Boam recalled. Eleven thousand prisoners were led out into weather that was below freezing and where the snow was six inches deep; their westward march of about 45 miles took four or five days to complete. “One night I was able to sleep in a barn in a pile of other bodies for warmth,” Albert noted. “Our destination was Spremberg in Saxony. But we did not remain there long.”

The prisoners were split up and sent in different directions. On February 2, the men of the north compound, including Albert, were loaded onto boxcars and shipped to Stalag XIII-D at Nuremberg. The city looked to Albert to be about 90 percent destroyed. He recalled a scene from the movie Judgment at Nuremberg that depicted the city in that condition. The camp, which was previously occupied by Italian prisoners, was infested with lice.

Conditions deteriorated. Because of the chaos and disruption in Germany, much of it due to continuous Allied bombing and strafing, no new Red Cross parcels arrived for the prisoners for several weeks. As a result there was little to eat, and the men began to lose weight. “I lost about 25 pounds,” Albert said. Conversations were dominated by talk of food. Even women took a back seat in these barrack conversations. When a shipment of parcels finally arrived, it was greeted with great celebration. Albert remembered, “It was like V-E Day—we were all so happy to have food again.”

Soon, however, the camp was threatened once more—this time from the west as the Americans and their allies crossed the Rhine and rushed eastward. This time the weary prisoners were marched southward to Bavaria. “It was early spring, and at least the weather was pleasant,” Albert noted. The Germans were short of manpower by now, and the POWs were guarded almost informally by older men of the type drafted into the Volkssturm at the end of the war. Albert recalled, “The prisoners could have escaped if they had wanted to, but we all knew that the war was almost over and no one wanted to risk being shot before we were liberated.”

One day as they shuffled past a local farm, Albert walked up to the farmer who was watching them pass and attempted to trade some of his cigarettes for eggs. The American had picked up a little German, and the farmer understood what he wanted. During the exchange, however, the farmer informed Albert out of the blue that President Franklin Roosevelt had died. The news soon spread, and it was a shock to everyone.

The POWs’ last stop was in a camp near Moosburg, a town northeast of Munich. While the prisoners settled into their new camp, they saw a silver North American P-51 Mustang fighter fly low overhead; everyone stood and cheered. Albert recalled, “That same day, down in Moosburg, we heard small-arms fire and then—the greatest of sights—the American flag was hoisted above the village church steeple.” Their remaining guards just wandered away, and the prisoners were liberated.

Not long after that, General George S. Patton himself rode into the makeshift camp sitting on top of the rear seat of his jeep. The jeep stopped, and Patton stood on the jeep so he could be seen and delivered one of his trademark speeches to the exhausted prisoners. Albert remembered that Patton “thanked us for our service and called the Germans SOBs. A few days later we were evacuated by C-47s to Rheims in eastern France. When we arrived, the celebrations for V-E Day were already underway.”

It wasn’t long before the former POWs were moved to the northern French port of Le Havre. There they were housed at a camp called “Lucky Strike” while being processed for the trip home. While there, they were given as much food as they wanted and started to gain weight again.

When the day came for departure, Albert was sent aboard a troopship named the SS Marine Raven. Again, the former POWs got all they wanted to eat and the weight gain continued. Albert said, “My prewar weight was about 154 pounds; I got down to 125 pounds in camp. By the time I reached home, I was up to 167 pounds.”

The Marine Raven put to sea in a convoy of about 20 ships, all headed home. Most of the ships headed straight for his hometown of New York, but the Marine Raven was bound for Boston. Albert never found out why. From there he was sent to Westover Air Force Base in western Massachusetts.

Albert was then ordered to report to Fort Dix, New Jersey. There he finally got some dental work done for his chipped tooth. The dentist cemented an acrylic crown over the tooth, and as a bonus Albert met the nurse and dated her a couple of times. Also at Fort Dix, he received nine months of back pay for the time he was a POW; it totaled about $3,000. He felt rich. He was also given 60 days leave.

On the train home to New York, Albert met a young woman. “I still remember her name,” he recalled. The two hit it off well during their train ride. By the time they reached Pennsylvania Station in New York City, he had talked her into spending the night with him and they rented a nearby hotel room. “She was a beautiful Irish girl,” he recalled. “So I was a day late in getting home,” he smiled.

It was a very nice leave. Albert had money in his pocket and the will to have a good time. “Breakfast consisted of bourbon and steaks—and sometimes lunch, too.” While he was on leave, the Japanese surrendered. He was in Atlantic City, New Jersey, at the time, which probably had its biggest party ever. “I certainly drank my share,” he recalled.

Because he had been a POW, Albert was given the opportunity to go to a “rest camp” in Asheville, North Carolina, and he accepted. More parties ensued. Finally, in November 1945, he was separated from the military. He had earned eight battle ribbons and wore them proudly. Albert remained in the Air Force Reserve for 10 years.

During that time, he attended Columbia University on the G.I. Bill. He then went to work for an advertising agency in New York. Asked what life was like in the “ad game,” he replied, “Booze and broads, mostly.” He married in 1958, but it didn’t last long and there were no children.

Once, in conversation with his financial adviser, he was asked if he wanted to invest in the German company I.G. Farben—the company he was trying to bomb on the day he was shot down. He declined the offer.

Today, at age 92, Albert Boam enjoys life in a retirement community in Stone Mountain, Georgia.

Interesting account. My dad and uncle were Eighth AF B-24 vets. As a native Tennessean, this is the first I’ve ever heard that there was a classification camp at Nashville. There was an Air Transport Command B-24/C-87 training base at Smyrna.