By Mike Phifer

Ignoring the scorching summer heat, Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Wellesley climbed one of the towers on the ruined estate of Casa de Salinas 80 miles southwest of Madrid, Spain, to survey the surrounding countryside. It was July 27, 1809, and the British commander could see the two brigades of Maj. Gen. Randoll Mackenzie’s Third Division along the Alberche River screening the Anglo-Spanish forces that were taking up position near Talavera de la Reina a few miles to the west. Wellesley was not, however, looking for his own troops, but those of the French. His eyes soon fixed on the advance of thousands of French soldiers.

The French soldiers of General Pierre Lapisse’s Second Division, which led the way for Marshal Claude Perrin Victor’s I Corps, moved stealthily through the nearby woods towards Wellesley’s screening force. They quickly surprised lax British pickets and rushed toward Colonel Rufane Shaw Donkin’s Brigade who was resting in the shade of some trees. The crash of musketry caused the British troops to scramble to arms and attempt to form up. Some did not make it.

The sudden fierce French attack drove back the soldiers of Donkin’s Brigade and the 2nd Battalion of the 31st Foot of the Mackenzie’s own brigade. Wellesley scrambled out of the tower and rode away. He barely escaped capture by the French troops.

Part of the green-coated 5th Battalion of the 60th Rifle Regiment fired into the flank of Marshal Victor’s I Corps. At the same time, the 1st Battalion of the 45th Foot began firing rolling volleys into the French. The heavy fire from the British slowed the French advance.

Wellesley and the officers of the broken regiments quickly rallied their disordered troops. Under the cover of two supporting regiments and light cavalry, Donkin’s two brigades withdrew to the main British line north of Talavera. The British lost more than 440 men in the late afternoon clash.

Victor followed the withdrawing British units. When he encountered Wellesley’s main line, he ordered his artillery into action. In the gloaming, French guns began to hammer away at the British. The British artillery returned fire, but were badly outnumbered.

The artillery duel that lit up the evening unnerved the Spanish troops, allied with the British. When they spotted French cavalry, four Spanish battalions composed of green troops mistakenly fired at the French horsemen without orders. The Spanish fled to the rear apparently “frightened by the noise of their fire,” wrote Wellesley. It was bad enough that they fled their positions, but the Spanish troops then plundered the baggage of the British army.

The artillery soon quieted down for the night. Word spread through the British ranks that the French likely would attack the next morning; however, Victor had other ideas. Once the rest of his corps came up, he intended to attack Wellesley’s line in the darkness of night. In that way, the French marshal sought to obtain a quick victory over the British. But he failed to factor into the equation the resoluteness of the British rank and file and the tenacity of their intrepid commander.

The long war between France and Britain spread to the Iberian Peninsula during the War of the Fourth Coalition. After a sea invasion of Great Britain proved impractical in 1805, French Emperor Napoleon sought to defeat Great Britain economically the following year by establishing a Continental System through which he could control British trade with the European mainland. After his victory over the Austrians in the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon became determined to force the Portuguese to close their ports to the British.

When the Portuguese crown refused, he sent General Jean-Andoche Junot with 30,000 troops to forcibly close the ports. With British assistance, the Royal Court of Portugal fled to Brazil, and Junot occupied Lisbon on November 30, 1807. Believing he might acquire additional territory in Portugal, Spanish King Charles IV agreed to assist the French in conquering Portugal. But Spain soon grew unstable, owing to the corrupt rule of its Bourbon royal house. In an attempt at reform Charles was replaced by his son, Ferdinand VII, who ruled for less than two months.

Taking advantage of the situation, Napoleon occupied Spain in March 1808 and subsequently proclaimed his elder brother Joseph Bonaparte as the new king of Spain. While the transfer of power was under way, the residents of Madrid revolted on May 2 and attacked the French garrison. Spain soon became engulfed in revolution, giving the British an opening to intervene militarily in the affairs of both Portugal and Spain. Despite the unrest, Joseph was crowned King of Spain on June 6.

Wellesley, at that time a major general, landed in Portugal with 18,000 troops on August 1. Junot boldly attacked the British position at Vimeiro 30 miles north of Lisbon on August 21. Heavily outnumbered, Junot launched piecemeal attacks that the highly disciplined British infantry easily shattered with accurate musket fire.

London recalled Wellesley, who they promoted to lieutenant general for his victory at Vimeiro, and replaced him with a more senior commander. Lt. Gen. Sir Hew Whitefoord Dalrymple arrived in Portugal to succeed Wellesley as commander of the British expeditionary force, but was removed from command after he signed a truce with Junot that angered London. Next, British Lt. Gen. Sir John Moore arrived to take command of the British expeditionary force. Moore invaded Spain in November 1808 to support the rebellion, but retreated north when Napoleon arrived with a large army determined to annihilate his army.

However, Napoleon soon departed for Paris to prepare to go to war again with Austria, leaving the pursuit of Moore to Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult. Moore withdrew to the port of Corunna in northwest Spain for extraction by a British fleet. In a sanguinary clash on January 16, 1809, at Corunna while the British were preparing to board the transports, the French attacked the British position two miles south of the port. Moore fell mortally wounded while rallying one of his units. His death would see Wellesley return for a second tour of duty on the Iberian Peninsula.

Soult eventually occupied Oporto, Portugal, but did not move quickly enough on Lisbon where Portuguese forces had fortified the city. Wellesley arrived in Lisbon in late April to great fanfare by the Portuguese. He quickly drove Soult out of Oporto and sent a dispatch to Captain-General Gregorio Garcia de la Cuesta, the commander of the Spanish army of Estremadura, in which he suggested a joint operation against the French forces in Spain. Cuesta, who commanded 30,000 men, accepted the proposal. Leaving the Portuguese army to defend its homeland, Wellesley set out with his British army in late June for the Spanish frontier.

The British army consisted of 22,000 men organized into four infantry divisions and a cavalry division. Maj. Gen. John Sherbrooke led the 1st Division, Maj. Gen. Rowland Hill led the 2nd Division, Maj. Gen. Mackenzie led the 3rd Division, and Brig. Gen. Alexander Campbell led the 4th Division. The cavalry division, commanded by Lt. Gen. William Payne, consisted mostly of dragoons. Wellesley had 30 guns in five batteries. Each infantry division had an artillery battery, and one was held in reserve.

Wellesley’s British army reached Plasencia, Spain, which was 80 miles west of Talavera, on July 9. The following day he departed with an escort on a 40-mile ride to meet with Spanish commander Cuesta at Casa de Miravete near Almaraz. Arriving after dark, he reviewed Cuesta’s troops by torchlight.

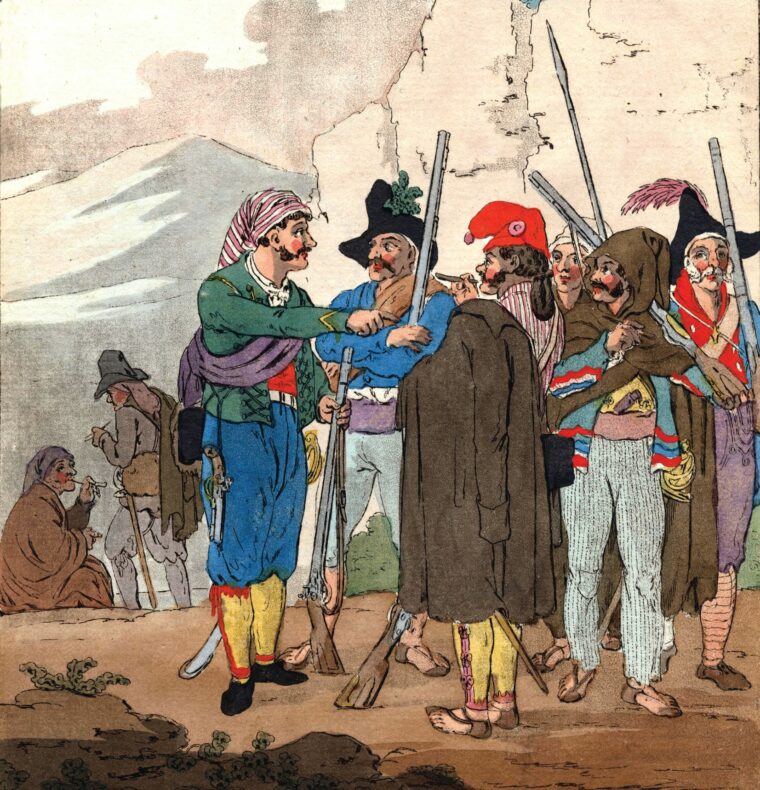

Wellesley did not like what he saw. For one thing, the Spanish officers lacked the degree of professionalism to which Wellesley was accustomed. In addition, the soldiers lacked good weapons and many did not have shoes. “[They were] little better than bold peasantry, armed partially like soldiers, but completely unacquainted with a soldier’s duty,” recalled Brig. Gen. Charles Stewart, who had accompanied Wellesley to the meeting.

The next day Wellesley had a tense four-hour meeting with the elderly Spanish general in which the two Allied commanders hashed out a plan. They decided to advance west along the Tagus River to Toledo and continue on to Madrid. Spanish guerillas had gathered good intelligence on the size and location of the French forces in Spain, and Cuesta passed along this information to Wellesley.

The intelligence indicated that General Victor had deployed the 20,0000 troops of his I Corps behind the Alberche River northeast of Talavera, and that General Horace Sebastiani’s IV Corps, which also numbered 20,000 troops occupied a position at Madridejos 100 miles southeast of Talavera. In addition, King Joseph and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan had with them 12,000 troops at Madrid. King Joseph was the nominal commander of the French forces in Spain, but Jourdan, who was his chief of staff, served as the de facto commander. These three forces could concentrate within two days at Toledo, which was 55 miles east of Talavera.

Several other French corps in northwest Spain posed a threat to the operations of the Anglo-Spanish army—either by reinforcing the forces that eventually would face the British at Talavera or by threatening Wellesley’s lines of communication to Portugal. These included Marshal Soult’s II Corps, General Edouard Mortier’s V Corps, and Michel Ney’s VI Corps.

Napoleon, who was campaigning against the Austrians, sent a message to Joseph, which his brother received on July 1. The message instructed him to combine the three French corps in northern Spain into one army under Soult. “These three corps must maneuver as a single body, pursue the English relentlessly, defeat them, and throw them into the sea,” wrote the emperor. But Napoleon assumed Wellesley was defending Lisbon, and he had no idea that Wellesley had invaded Spain.

Wellesley dispatched Sir Robert Wilson with a flank column of 1,500 troops to screen Wellesley’s army against possible attack by any of the French forces that might arrive from northern Spain. For his part, Cuesta agreed to send General Francisco Javier Venegas’s 26,000-strong Army of La Mancha to tie down Sebastiani and prevent him from joining the French army facing Wellesley; however, if Sebastiani should slip away to join Victor, then Venegas had orders to seize Madrid.

A sticking point, though, concerned the drastic supply situation facing Wellesley’s expeditionary army in Spain. The area through which the British were marching had long since been stripped bare by French and Spanish forces. Wellesley threatened to withdraw his army if Cuesta failed to furnish his troops with provisions and wagons or carts to transport them. But the Spanish initially demanded payment for supplies. Wellesley received some funds from London before he entered Spain. Frustrated with the ongoing supply problem once he had crossed the Spanish frontier, Wellesley marched his troops to Oropesa where they rendezvoused with the Spanish on July 20. The Spanish, though, did not furnish any provisions to the British.

The British and Spanish armies set off two days later on parallel routes for Talavera, and on the way Spanish cavalry skirmished with French dragoons at Gamonal. When British cavalry came up, the French dragoons, who screened the main body of the French army, withdrew east to rejoin Victor’s I Corps east of the Alberche River.

Wellesley urged Cuesta to participate in an attack the following day against Victor, who would be outnumbered by more than two to one by the Anglo-Spanish army. British troops moved into position during the night ready to pounce on the French at daylight, but to Wellesley’s dismay the Spanish army failed to show up. Victor withdrew his corps and sent word to King Joseph and Jourdan that the British were nearby.

Cuesta wanted the Anglo-Spanish army to pursue Victor on July 24, but Wellesley refused to do so until the Spanish furnished the provided the rations they had promised to give the British. By that time, the British troops had been subsisting on half rations.

But Wellesley did order Sherbrooke’s 1st Division and Mackenzie’s 3rd Division, as well as a detachment of cavalry, to cross to the east bank of the Alberche. While the British vanguard deployed, Wellesley reconnoitered the ground north of Talavera for a suitable defensive position should Jourdan reinforce Victor.

Cuesta, with whom Wellesley found it increasingly difficult to coordinate operations, eventually led his army in pursuit of Victor. “I should certainly get the better of everything,” Wellesley wrote, “if I can manage General Cuesta; but his temper and disposition are so bad, that it is impossible.”

As the Spanish army approached Torrijos, which was 25 miles beyond the Alberche, it came upon a consolidated French army under King Joseph that numbered 46,000 troops. King Joseph’s Army of the Center comprised Victor’s I Corps, Sebastiani’s IV Corps, and a Reserve of three cavalry divisions from the French garrison at Madrid. Cuesta hastily withdrew his army, which reached the British position on the east bank of the Alberche on July 26. The following day Wellesley convinced Cuesta to cross to the west bank of the river where Wellesley had marked out positions for both armies. Sherbrooke’s and Mackenzie’s divisions covered the withdrawal of the Spanish army.

Wellesley’s strong defensive position on July 27 stretched for two miles from Talavera to a 300-foot ridge known as the Medellin Hill. With its steep eastern face, the hill would furnish a place to anchor the British left flank. A lower ridge, known as the Cascajal Hill, was left unoccupied. A shallow stream, the Portina, flowed south from the Sierra de Segurilla mountains to the north, passing between the two ridges and eventually emptying into the Tagus River.

Wellesley directed Cuesta to deploy the bulk of his Spanish troops in three lines just north of Talavera, which was adjacent to the wide Tagus River. He did this partly because he knew the northern outskirts of the town consisted of buildings, stone walls, and cultivated fields that would afford ample cover for the mostly green Spanish troops. He also knew that the Spanish were incapable of maneuvering in battle. Cuesta’s troops further strengthened their position by constructing makeshift breastworks.

Wellesley ordered Brig. Gen. Henry Campbell, who commanded the light infantry brigade of the 1st Division, to deploy on the east bank of the Portina to watch for the arrival of the French army.

He placed a British battery in earthworks atop a small rise known as Pajar de Vergara to anchor his right flank. Campbell’s 4th Division deployed in two lines to the left of the battery. Sherbrooke’s 1st Division deployed in the center of the British position with some of its troops on the southern slope of the Medellin Hill. The British front line continued north with Hill’s 2nd Division squarely atop the Medellin Hill.

Wellesley placed Mackenzie’s 3rd Division and the British cavalry in a second line behind Sherbrooke to strengthen the British center. On the far left, beyond the Medellin Hill, Wellesley placed Brig. Gen. George Anson’s brigade of cavalry to screen the British left. The Allied army’s reserve consisted of a Spanish infantry division and a Spanish cavalry division commanded by Lt. Gen. Jose Maria de la Cueva, the Duke of Albuquerque.

When Victor arrived with his 1st Corps, he deployed his troops facing the British. His 1st Division, which was led by General Francois Ruffin, went into position atop Cascajal Hill. Once the infantry had secured the ridge, French troops manhandled artillery to the top of the rise and opened fire on the British. At the same time, French cavalry probed the Spanish positions to the south.

When the French guns fell silent at nightfall, Victor prepared to seize Medellin Hill in a night assault. He had observed that the British position on the high ground was not strong and sought to take advantage of the perceived weakness.

After dining in Talavera, General Hill returned to Medellin Hill where to his dismay he discovered his two brigades were not in their assigned positions. Maj. Gen. Christopher Tilson’s 1st Brigade and Brig. Gen. Richard Stewart’s 2nd Brigade had allowed their troops to encamp a half a mile from their assigned positions on the reverse side of the hill. The redcoats of Colonel Donkin’s battered brigade of the 3rd Division, after their earlier retreat, had taken up a position on the southern slope of the ridge. As for the two King’s German Legion brigades of Sherbrooke’s 1st Division, which were led by brigadiers Ernest Langwerth and Sigismund von Low, they held a position to the southeast.

Victor intended to use Ruffin’s Division to attack and seize Medellin Hill, while Lapisse’s division created a diversion against the British center. Without bothering to seek permission from King Joseph, Victor ordered his men to advance at 10 p.m. Ruffin’s men moved forward in the dark in three regimental columns with the 9th Light Infantry in the center, 24th Line Infantry on the right, and 96th Line Infantry on the left.

In the darkness the 9th Light Infantry veered south and stumbled into the sleeping troops of Low’s Brigade. Surprised and confused in the dark by the French bayonet attack, the 7th and 5th battalions of Low’s Brigade quickly gave way with heavy casualties. The 96th Line Infantry, though, had come under fire from Langwerth’s Brigade which stalled its attack. The 24th Line Infantry attack fared little better as its troops became disoriented in the darkness. Wandering in the darkness, they strayed too far north of Medellin Hill.

The 9th Light Infantry continued its advance by pushing up the hill; in so doing, it flanked Donkin’s Brigade. Meanwhile, General Hill prepared Stewart’s Brigade to aid the Germans, although he did not believe they were being seriously threatened. The general rode with another officer to the top of the hill where he could see French musket flashes.

Hill soon found himself among enemy skirmishers who tried to capture him. Although his horse was wounded, he was able to gallop back to his troops; however, the officer accompanying him was slain. When Hill reached the relative safety of his troops, he ordered the 1st Battalion of Detachment, a battalion cobbled with companies from various units, to stop the French advance.

With shouts of “Vive l’Empereur,” the French troops pressed their advance. Flashes of musketry could be seen in the darkness as the 9th Light Infantry fired on the British. The French seized “some of our men by the collar and were dragging them away prisoners,” wrote Sergeant Nichol of the 92nd Gordon Highlanders. The French captured 200 British prisoners, even though many of those captured managed to escape in the darkness.

Hill, who was still on his bloodied horse, led the 29th Foot of Stewart’s 2nd Brigade into the fray. They fired a volley at the French and then charged the enemy with their bayonets. The French, who reeled in the face of the counterattack, retreated down the hill with the redcoats in pursuit. Their powerful volleys repulsed another French column as well. In the face of such stubborn resistance by the cream of the British army, the French withdrew from the hill.

Victor’s night attack, which lasted for about an hour, achieved nothing. The French lost 300 men, while the British lost 400 men. The King’s German Legion battalions of Sherbrooke’s 1st Division incurred half of the British losses.

The French commanders had every intention of launching a full-scale attack at daylight. The French lit torches during the night not only to guide troops that were arriving on the field from their long march, but also to illuminate the work of artillerymen and engineers who toiled to construct earthworks atop Cascajal Hill for multiple batteries.

British officers had their men up before dawn in order to prepare for a fresh assault by the enemy. When the sun finally rose on July 28, French forces could be seen deploying for an assault on the British line. Victor’s I Corps was still at Cascajal Hill facing the British left and center, while Sebastiani’s IV Corps faced the British right above the Pajar de Vergara battery.

General Victor sent word to King Joseph of his plan for a major assault to which King Joseph reluctantly agreed. Victor intended to strike against Medellin Hill with the main attack entrusted to Ruffin’s 1st Division. Lapisse’s 2nd Division would make a diversionary attack against the British forces holding the southern slope of the ridge. General Jean Francois Leval’s 3rd Division of Sebastiani’s IV Corps would be responsible for pinning down the troops on the British right. As for General Eugene-Casimir Villatte’s 3rd Division, it would serve as the French reserve.

One of the batteries on Cascajal Hill fired a single round at 5 a.m. that served as a signal for a French artillery bombardment to begin. Upon that signal, 54 French cannon roared to life. The French gunners on Cascajal Hill plastered Medellin Hill with grapeshot and shell.

Throughout the Peninsular War, the British army faced a chronic shortage of artillery. The British had just 18 guns on the Medellin Hill with which to respond to the French artillery. The French gunners succeeded in silencing many of those guns.

As the French artillery fire slammed into the British positions on Medellin Hill, British officers ordered their men to lie down in efforts to save them from the hell being hurled at them. “The men were all lying in the ranks, and except at the very spot were a shot or shell fell, there was the least motion,” wrote Ensign John Aitchinson of the 3rd Foot Guards of Henry Campbell’s Brigade. After 45 minutes, the French guns fell silent.

Cannon smoke obscured the view of the British troops, but they could hear the French drums that signalled an advance. French skirmishers known as voltigeurs fanned out in front of dense infantry columns. The voltigeurs steadily forced back the British skirmishes facing them.

As the cannon smoke cleared, General Hill could see the French columns moving up the rocky slope. When the troops of the 24th Line Infantry closed to within 100 yards of the ridge line, Hill ordered his six battalions of infantry to stand up. They marched to the edge of the ridge where they fired crashing volleys at the French. The storm of British lead staggered the head of the French columns. Dazed survivors at the front of the French columns returned a ragged fire, but with little effect.

With the French formations in disorder, Hill ordered a bayonet charge. With their bayonets glittering in the sunlight, the redcoats surged down the hill. This was too much for the battered soldiers of the French 24th Line Infantry who fled across the Portina. The 96th Line Infantry attempted to assist them, but the 5th Battalion of the King’s German Legion struck their flank.

Some of the charging redcoats crossed the Portina and pushed on toward Cascajal Hill. The French mowed down a substantial number of these troops, and the surviving British fell back to their lines. French guns pounded the British line for an hour. The French lost 1,300 men, while inflicting 750 casualties on the British. Both sides gathered their dead.

The French soldiers then began to cook their breakfast, while the half-starved British foraged for whatever they could find. Under the scorching sun of the summer morning, both sides drank from the tainted waters of the Portina stream.

The French high command convened on Cascajal Hill to discuss its next course of action. Victor wanted to renew the attack on the British with the assistance of Sebastiani’s fresh troops, which were still arriving on the field. But Joseph, Jourdan, and Sebastiani all preferred to withdraw in order to cover Madrid and Toledo. The consensus was that Soult would attack the British rear when he arrived in a few days—then a messenger arrived with word that Soult had been delayed and would not arrive until early August—so Joseph agreed to renew the attack on the Allies in the hope of achieving a decisive victory.

Instead of attacking Medellin Hill head-on Joseph and Jourdan told Victor that he was to try to attack the strategic position from the northern plain that lay south of the southern slopes of the Sierra de Segurilla. Meanwhile, Sebastiani’s troops would deliver the main attack against Wellesley’s center. Because the French did not consider the Spanish troops to pose any real threat, they left them alone altogether.

In preparation for another attack against Medellin Hill, Wellesley instructed General Donkin to shift his 2nd Brigade of the 3rd Division closer to the summit of the hill. Wellesley rightfully sensed that the French would try to outflank the position from the north.

He also reinforced his left flank by deploying two cavalry brigades from his reserve along on the western end of the northern plain. These were Brig. Gen. Henry Fane’s 1st Heavy Cavalry Brigade, and Brig. Gen. George Anson led the 3rd Brigade. Anson’s brigade comprised light dragoons and hussars. Wellesley also ordered several cannon into position on the northern slope of the hill and ordered some infantry to march across the northern plain and take up positions on the lower slopes of the Sierra de Segurilla where they could help foil the anticipated assault on the British left flank.

When Wellesley saw dense clouds of dust to the east indicating that French reinforcements were arriving on the field, he sent an urgent request to Cuesta for reinforcements. The Spanish commander responded positively by dispatching Maj. Gen. Don Luis Alejandro de Bassecourt’s Reserve Division of 5,000 troops, the Duke of Albuquerque’s Cavalry, and a battery of 12-pounders.

Two Spanish heavy guns went into action west of the King’s German Legion Battery, while the four other guns buttressed the British battery at Pajar de Vergara. Albuquerque’s cavalry formed a second line behind Anson and Fane.

Eighty French cannon began pounding the British line at 2 p.m. in preparation for the third French attack of the battle. British foot soldiers hugged the ground in hopes of escaping the storm of iron. Although the main attack was scheduled to commence an hour later, Leval blundered by ordering his blue-coated infantrymen to advance half an hour early while the bombardment was still in progress. Struggling over stone fences and through olive groves, the French troops pressed forward toward the British line amidst the crashing artillery.

The soldiers of the Nassau Regiment resorted to a ruse in order to get as close to the British as possible without being fired upon. “Long live the English!” the green-uniformed soldiers shouted as they closed in on the British and the gunners of the Pajar de Vergara battery. The trick might have worked for a short time, but they revealed their identity when they shot at the British who promptly returned the fire. The British 2/24th Regiment poured heavy volleys into the right flank of the Nassauers. At the same time, the Spanish and British guns of the Pajar de Vergara battery mowed down an assault by the Nassauers who withdrew in disorder.

Redcoats from three of Campbell’s regiments pursued the retreating French, capturing six French guns which they quickly spiked. Showing great prudence, Campbell ordered his troops back into line in preparation for another French assault. Meanwhile, several German battalions of Leval’s Division assailed the Spanish position. Upon seeing their retreating comrades to the north, the Germans withdrew as well. Having suffered heavy losses, Leval attempted to rally his remaining troops.

Further to the north, the French launched an all-out assault with 15,000 troops against Sherbrooke’s division. Twelve French columns swept menacingly forward. Another dozen French columns advanced in support of the first wave. Several thousand French cavalrymen waited behind the massed infantry hoping to exploit a breakthrough if one occurred.

The French skirmishers fanning out ahead of the columns splashed across the Portina and pushed the British light troops back toward their own lines. The redcoats deployed in two ranks anxiously waited for the order to fire. Soon the French line infantry crossed the Portina as well.

British guns blazed away at the heads of the blue-coated columns. When the French infantry closed to within 50 yards of their troops, British officers ordered their men to fire. The rolling volleys of British musketry mowed down hundreds of French at a time. With the surviving French dazed by the deadly fire, the British swept the ground with a vicious bayonet charge. The surviving French infantry fled back across the Portina where they reformed behind the support columns.

Exhilarated by their success, three-quarters of Sherbrooke’s division chased the retreating French. Only Brig. Gen. Alan Cameron, who commanded the division’s 2nd Brigade, managed to keep his men on the near side of the Portina stream. Wellesley watched in dismay as one brigade of Guards and two brigades of the Kings German Legion crossed the stream and made straight for the columns of supporting French infantry.

The Guards and King’s German Legion troops on the east bank of the Portina soon found themselves overextended and facing possible annihilation. General Langwerth received a mortal wound in the confused fighting. The battered battalions undertook a fighting withdrawal, but they suffered heavy losses in the process. To his credit, Cameron ordered his men to fire on the French to cover the withdrawal of their fellow soldiers. The surviving troops of the Guards and King’s German Legion reformed behind the troops that saved them, showing their appreciation with a loud hurrah.

Fortunately for the British, General Mackenzie’s 3rd Division, which had been positioned behind the British center, moved into the position previously occupied by Campbell’s Guards. The French supporting columns surged forward against the British center. In the savage fighting that followed, Mackenzie was slain. The French attack stalled, however, and the British center remained unbroken.

Wellesley ordered the First Battalion of the 48th Foot of Hill’s 2nd Division to assist the King’s German Legion troops who had been badly mauled. The 1st Battalion of the 48th Foot rushed south from Medellin Hill and helped check the second wave of French columns assailing the British center. While urging his men forward in the blazing firefight on the west bank of the Portina stream, General Lapisse received a fatal wound. Seeing their commander slain, his soldiers broke off their attack and withdrew.

Another attack by Leval against the British center at 4 p.m. was repulsed with heavy casualties. As his troops were withdrawing, Spanish cavalrymen sabered many of those in the open before they reached the safety of their lines.

While the French attack on the British center was underway, 8,000 French infantry from the divisions of generals Ruffin and Villatte of Victor’s I Corps, supported by 1,200 French horsemen, advanced onto the northern plain between the Sierra de Segurilla and Medellin Hill. The odds in that sector were about even given that Wellesley had aggregated some 10,000 British and Spanish troops to oppose them.

British and Spanish guns raked the French columns as they advanced over the open ground. While the French 9th Light Infantry Regiment screened their exposed right flank, the troops wheeled left in an attempt to assault British positions on Medellin Hill. When the French attack on the British center ended, Wellesley had time to turn his full attention to the defense of his left flank.

He ordered his two cavalry brigades to attack the French infantry. Sending cavalry against infantry was a desperate measure that could only succeed under the best of circumstances. Wellesley ordered Anson to lead the attack and Fane to follow in support. Anson’s cavalry charged in two lines with the 23rd Light Dragoons on the right and the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion on the left. Seeing the cavalry thundering toward them, the French infantry quickly formed squares in order to repulse the attacking cavalry.

As the 23rd Light Dragoons galloped to within 150 yards of the enemy, the troopers discovered to their horror that they had come upon a deep 15-foot-wide ravine. Many of the horsemen in the first line fell into the ravine. Those that fell first suffered the worst as other horsemen following close behind them fell on them. Making matters even worse, nearby French infantry fired on them.

Most of the troopers in the second line of cavalry who saw the thrashing horses in the ravine mercifully pulled up. The survivors rallied and charged on against the French squares, but most of them were shot down or captured. The 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion fared little better. Many of the troopers in the first line tumbled with their horses in the ravine. The Hussars rallied and renewed their charge, but they did not press their attack against the French squares.

Despite the failed British cavalry attack, the French infantry did not attack Medellin Hill again. The Allied artillery fire, coupled with the news of the failed attack on the British center, compelled Ruffin and Villatte to break off their attack and return their soldiers to the safety of their own lines. The battle was over, although the suffering did not end as dry grass between the opposing lines caught fire. Many of those too badly wounded to walk burned to death in the flames.

It had been a costly day for the French who lost 7,300 men and 17 guns. The British lost 5,500 men, which amounted to a quarter of Wellesley’s army. As for the Spanish, they lost 1,200 men.

Victor wanted to continue the fight, and he therefore urged King Joseph and Jourdan to attack again. Neither had any intention of continuing the battle because they believed their army had suffered enough, and that their troops needed rest. Besides, they were concerned the Spanish, who were still fresh, might launch a flank attack. With the advent of nightfall, the French withdrew to the east side of the Alberche. Victor, who was still fuming over the reluctance of his superiors to continue fighting, did not begin withdrawing his troops until late evening.

Concerned over the safety of Madrid, Joseph left Victor’s 1 Corps on the banks of the Alberche to watch Wellesley and Cuesta. Meanwhile, the rest of the French army marched southeast towards Madrid. The French did win a small victory when Sebastiani defeated Venegas’ Army of La Mancha at Almonacid on August 11, 1809.

Wellesley received reports that Soult’s army was marching south in the hope of getting behind the British and cutting them off from Portugal. Although the Spanish wanted Wellesley to help them liberate Madrid, Wellesley needed to save his army. He therefore withdrew to Portugal in early August, leaving Madrid in French hands.

Five more years of savage fighting lay ahead before the Peninsular War ended with the French defeat in April 1814. In recognition of his victory over the French at Talavera, London bestowed upon him the title of Viscount of Wellington. The French in the Iberian Peninsula would come to dread that name.

Once again, fine article that would be vastly improved with some maps!

I feel like I should play Beethoven’s “Wellington’s Victory” while reading this article.

(Okay, that’s about Vittoria, but it’s close enough.)