By William E. Welsh

In the early weeks of the Second Boer War, General Jacobus Hercules De La Rey suggested a way to overhaul the tactics of his fellow Boers in a way that would prove devastating to his British opponents. Plunging fire from high ground had its limitations, he said during a war council held at Jacobsal, Orange Free State, at the outset of the conflict. For example, it could not stop disciplined British troops from reaching the dead spot at the base of the steep-sided rocky hills known as kopjes that were endemic to the African Highveld. A British force that reached this protected zone could rest before its final assault on Boer-held high ground.

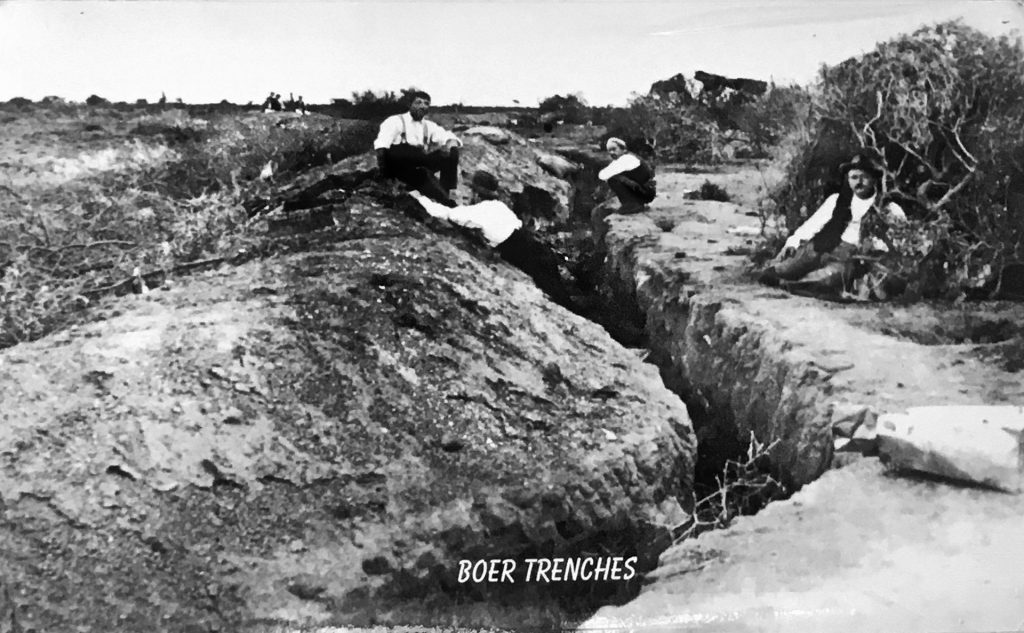

He therefore proposed a dramatic change in tactics that was designed to fully exploit the awesome firepower of the German-made Mauser rifle with which the Boers were armed. The Boers should deploy their front rank in trenches and rifle pits on the veld where they could sweep the ground up to 2,200 yards with their bolt-action, repeating rifles. De La Rey employed his new tactics in the pitched battle at Modder River on November 28, 1899. They were largely responsible for the Boer army’s decisive victory that day.

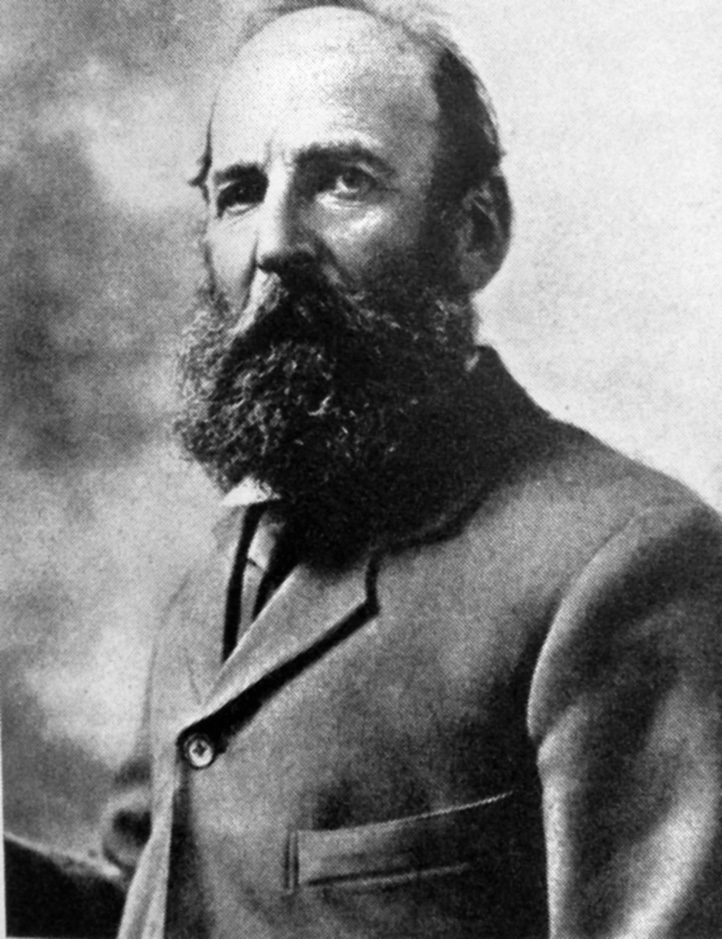

De La Rey was born on the Doornfontein Farm at Winburg in the Orange Free State on October 22, 1847. His ancestors were Spanish, French Huguenot, and, of course, Dutch. Eleven years before he was born, hundreds of Boer voortrekkers, or pioneers, migrated by wagon train from Cape Colony north beyond the Orange River in an effort to live beyond the stern grip of British colonial administration. When De La Ray was just one year old, a sharp battle over control of the land between the Orange and Vaal Rivers occurred on August 29, 1848, at Boomplaats along the Orange River. Pitted against British General Harry Smith’s 1,200 British troops were just 300 Boers led by Andries Pretorius. The Boers lost the battle, and the British eventually confiscated Doornfontein Farm.

The De La Reys resettled to Lichtenburg in the Transvaal. The family moved again in the 1870s to Kimberley in the western half of the Orange Free State when diamonds were discovered there. “Koos,” as he was called by family and friends, had little formal education. He found regular work transporting supplies for the Kimberley diamond mining operations.

Although he had no formal military training, Koos gained a wealth of experience fighting native tribes. He fought in the three-year Basuto War that began in 1865 and resulted in the absorption of most of King Moshweshwe’s lands into the Orange Free State. He also fought in the Boer clash with King Sekhukhune of the Pedi in 1876. These experiences in irregular warfare would prove invaluable during the latter stages of the Second Boer War. While serving as a veld cornet in the short-lived First Boer War of 1880-1881, he took over the direction of the Boer siege of the Potchefstroom when Piet Cronje became seriously ill.

De La Rey was elected commandant of Lichtenburg in 1883 and became a member of the Volksraad of the South African Republic (Transvaal). He was against President Paul Kruger’s war policy; instead, he was an ardent supporter of Piet Joubert, who had been the commandant-general of the republic during the First Boer War. Kruger, though, was a far shrewder politician. Kruger was so confident that a second war was imminent that he began stockpiling 1893/1895 Mausers from Germany. Of the 75,000 rifles in the South African Republic’s arsenal by the start of the war, 37,000 were lightweight Mausers that could be rapidly loaded and fired with five-bullet clips.

The Transvaal Ultimatum, which called for the British to withdraw their military forces from the border of the Orange Free State and remove from South Africa all recently arrived reinforcements, was approved in a secret session of the Volksraad in September 1899. De La Rey was one of seven members who voted against the ultimatum. In an address to the session, he pointed out the folly of going to war with Great Britain. However, he concluded his remarks by saying, “I shall do my duty as the Raad decides.”

De La Rey accepted a generalship at the outbreak of the Second Boer War on October 11, 1899. The Boers had begun mobilizing two weeks earlier. The armies of both the South African Republic and the Orange Free State were made up entirely of citizen soldiers between the ages of 16 and 60.

When the war began the Transvaal and Orange Free State fielded 23,000 and 12,000 soldiers, respectively. The troops were organized in units called commandos. The 52-year-old commandant received orders to assume command of Boer forces operating against the Cape Colony in the west. De La Ray was appointed to serve under the bull-headed General Piet Cronje as his advisor and second in command. The Boer strategy in the west was to secure the three key towns—Kimberley, Vryburg, and Mafeking—on the Western Railway north of the Orange River.

It was terrain with which Koos was intimately familiar. He would have the honor of leading Boer troops in what would be the first action of the conflict. Once this was accomplished, the Boers intended to invade Cape Colony. Meanwhile, Boer forces in the east would invade Natal and then march on the strategic port of Durban.

Like many Boers, Koos sported a thick beard. Standing six feet, one inch tall, he had a high forehead, thick eyebrows, and a hook nose. A stern religious man, he drove his troops hard in battle. Waving his leather riding whip, he was often heard in the thick of battle shouting, “God is on our side!” He succeeded primarily because of his practical nature, religious conviction, and charismatic leadership.

The war was only one day old when De La Rey led 800 Boer troops against 30 British “khakis” on an armored train heading north on the Western Railway for Mafeking. The Boers and British battled for five hours at a railway siding on October 12 until the British surrendered. A handful of British were wounded, but the Boers suffered no casualties. The train was carrying cannons, rifles, and ammunition. After securing his prisoners, De la Ray and his men offloaded the arms and ammunition. They then tore up some of the tracks and cut the telegraph.

After his success against the British armored train on November 25, De La Rey marched his force, which had been enlarged to 3,500 troops, to the confluence of the Modder and Riet Rivers, 25 miles southeast of Kimberley. The troops had six Krupp guns and three 1-pounders known as pom-poms.

The river cut deep troughs through the Highveld—in some places the river bed and its banks were 30 feet below the surface of the veld. Instead of posting his men behind the river to cover its crossings, the resourceful commander positioned his front ranks inside the deep cut of the river. This afforded the Boers excellent cover for the banks served as ready-made trench. The troops on the front line improved their position by stacking brushwood in front of their firing positions so that even their heads and shoulders were protected while firing. The rifle pits were on the south bank of the two rivers, while the artillery was spread out behind them on the north bank. Knowing that his fellow Boers were prone to flight because they lacked the discipline of professional soldiers, he deliberately placed the majority of his troops on the south side of the river. This would make it difficult for them to flee as they would have to cross to the north bank while under fire.

Throughout the following day, De La Rey supervised his troops as they converted nearby farm buildings into strongpoints, dug rifle pits, and marked out ranges for their weapons. Cronje arrived after all of the dispositions had been made. The two commanders did not like each other, but Cronje found De La Rey’s preparations to his satisfaction. Rather than stand around appearing not to be doing much, Cronje retired to a small inn near the confluence for a good night’s rest.

On November 27, Lt. Gen. Lord Paul Methuen led his 8,000 troops north from the railroad stop at Enslin toward the Boer position along the Modder. After marching 14 miles, the British bivouacked six miles south of the river. Methuen sent mounted scouts to reconnoiter the Boer position, and they reported that the Boers were deployed in force near the collapsed railroad bridge.

Methuen rode forward to see for himself. As he swept his glasses along the river, which was marked by willows and bushes, he could not see any of the enemy troops. If the Boers were deployed along the river, their numbers must be small, Methuen reasoned. The ground between the blue-tinged Magersfontein Heights in the far distance on the north side of the river and everything in between seemed devoid of human presence.

Methuen would have been better served by sticking closer to the Western Railway and trying to fight his way across the Modder at Jacobsdal. This would have allowed him to march straight past the Boers into Kimberley. His decision to assault the enemy in a strong defensive position came from his keen desire to defeat the Boers in a pitched battle.

The following day, the British advanced toward the river. Methuen estimated there were only 400 Boers contesting the position. Cronje emerged from the inn to watch the British deploy for battle. As he did so, he ordered two guns shifted from the center to the left. De La Ray was furious because the movement of the guns gave Methuen valuable information on the Boer position.

Having spotted the Boer guns, a battery of British horse artillery began shelling them from a distance of 4,000 yards. With shells crashing all around them, the Boer artillerymen decided to withdraw their guns. Shortly afterward, Methuen gave the order to advance. By that time, they were within 1,200 yards of the Modder.

The crack of hundreds of Mausers rang out as Boer riflemen in a four-mile line poured out a steady fire that pinned the British to the ground. Some of the more fortunate British soldiers were able to take cover behind anthills. The Mauser fire proved devastating. The British troops found it difficult to return fire for they could not see the enemy. This was not only because the Boer riflemen were so well camouflaged, but also because the Mausers used smokeless powder that did not betray their position like traditional black powder.

“It’s fighting against rocks,” said a frustrated British soldier. “You have nobody to shoot at, dammit!” In his extreme frustration, Methuen led a detachment of Highlanders forward through a gully, hoping to dislodge some of the Boers. During the unsuccessful effort, Methuen was shot in the thigh.

Methuen’s valiant artillerymen moved up to within 800 yards of the Modder. They pounded the enemy’s right wing so hard that the Boer riflemen withdrew across the river late in the day. This allowed some of the British infantry to get a foothold on the north bank.

Koos’ 19-year-old son, Adaan, was mortally wounded during the fighting and taken to the rear. De La Rey personally oversaw the withdrawal of the Boer guns to ensure they did not fall into British hands. The British won the battle since they forced the Boers to withdraw. However, they suffered 400 casualties while the Boers suffered only 75.

When Cronje rode over to discuss the action with De La Rey, the weary commander lashed out at his superior for failing to help control the retreating troops. Afterward, De La Rey sought out his dying son. He sat beside him as he drew in his last breaths. He wrote to his wife telling her of their loss. “Tomorrow the body will be committed to earth in Jacobsdal,” he wrote. “How hard it is for us all. But God has decided [it this way].”

Afterward, the Boers gradually fell back to Magersfontein Heights. After 10 days of fighting, both armies had been heavily reinforced. The Boers now had 7,000 men and 10 guns, and the British had upward of 15,000 men and 33 guns. The heights rose 190 feet above the surrounding land. To their front were two parallel folds of ground that stretched for more than two miles.

De La Rey envisioned a similar defense to that at the Modder River. The Boers would entrench on the plain in front of the kopjes. He ordered his infantry to dig rifle pits and trenches deep enough so that they could fire standing up. De la Ray planned to put his best troops in the front rank firing Mausers. Their precise location would be hard for the enemy to determine because of the smokeless powder. Behind them in a second row would be the less experienced troops armed with antiquated Martini-Henry rifles.

Methuen decided to try outflanking the Boers by moving to the east to get around their left flank. This was precisely what the Boers had hoped he would do because it would allow them to enfilade his left flank as he advanced diagonally across their front. Methuen tried to march across the Boer front at night on December 10, but as the sun began to rise the following day the British were still slogging forward in tight formation. The Boers in their trenches laid down a sheet of fire that inflicted 950 casualties on the British at the cost of just 300 Boers. De La Rey had succeeded in stopping cold the British offensive in the west.

Lord Frederick Roberts took over command of all British and Commonwealth forces and set out in mid-February 1900 to relieve Kimberley. Roberts won a decisive victory over Cronje at Paardeberg on February 18. Afterward, the British forces encircled Cronje’s army and forced its surrender nine days later. Four thousand Boer soldiers went into captivity. De La Rey withdrew to the outskirts of Johannesburg. He had just 1,500 men, of which 1,000 were Johannesburg policemen.

Roberts advanced rapidly into Transvaal, capturing Johannesburg on May 30 and Pretoria six days later. The nature of the war had been changing for the past several months as the British erected blockhouses to protect strategic locations and the Boers resorted to guerrilla actions meant to disrupt their operations. De La Rey set up a base of operations at Magaliesburg northwest of Johannesburg. On July 11, his veteran cavalrymen surprised the Scots Greys in their camp at Zilikat’s Neck. The swift raid, which was an embarrassment for the British, resulted in the surrender of the regiment and the capture of 189 men.

Roberts departed for England in November. He was replaced by Lord Herbert Kitchener. The new British commander in chief would use new tactics, such as large-scale sweeps, in an attempt to capture Boer raiders.

On December 2, De La Rey attacked a British wagon train east of Rustenburg in western Transvaal, inflicting 118 casualties and capturing more than 100 wagons. Not finished with the British in the area, he spent three days reconnoitering the camp of Brig. Gen. Ralph Clements’ 1,500 troops near Nooitgedacht west of Pretoria.

Clements had made his camp at a waterfall in the Magaliesberg Mountains. After receiving substantial reinforcements led by Christaan Beyers that raised his cavalry corps to 2,100 troopers, De La Rey planned an attack that called for three columns to strike at dawn on December 13. Beyers, who commanded a column, had hoped to quickly overrun the 300 pickets at the top of the mountain, but a sharp firefight unfolded. De La Rey led a column that advanced against the main camp from the south, while Commandant Christoffel Badenhorst advanced on it from the west. De La Rey and Beyers, who shared responsibility for the operation, ultimately overpowered the British, inflicting 300 casualties and taking the same number prisoner at the cost of just 78 Boer casualties.

Although some of the Boer leaders began losing heart in 1901, De La Rey and Christiaan de Wet, who oversaw guerrilla operations in the Orange Free State, urged them to continue resistance to the British. In response to Kitchener’s draconian policies, in June of that year they began plotting an invasion of Cape Colony in an effort to discredit him. Meanwhile, Kitchener continued his sweeps through the Highveld in the hope of capturing the two guerrilla leaders. Kitchener tasked Methuen with capturing De La Rey.

De La Rey captured a British supply train at Yzer Spruit on February 24, 1902. A short time later, he turned the tables on Methuen when he attacked his rear guard at Tweebosch on March 7. In the sharp firefight, Koos’ troopers inflicted 200 casualties and captured 850 British prisoners, one of whom was Methuen. In a humanitarian gesture, De La Rey released Methuen because of his poor health. It was one of the two final pitched battles of the war.

At the outset of World War I, Koos considered leading an uprising against the British for which he might receive support from the Central Powers. This was never to be, though, for he was killed when his car crashed into a police roadblock in September 15, 1914.

De La Rey was one of a handful of Boer leaders who emerged from the war with their military reputations intact. His tactical genius and fortitude in the face of heavy odds ensured his inclusion in the Pantheon of great Boer commanders.