By Robert L. Durham

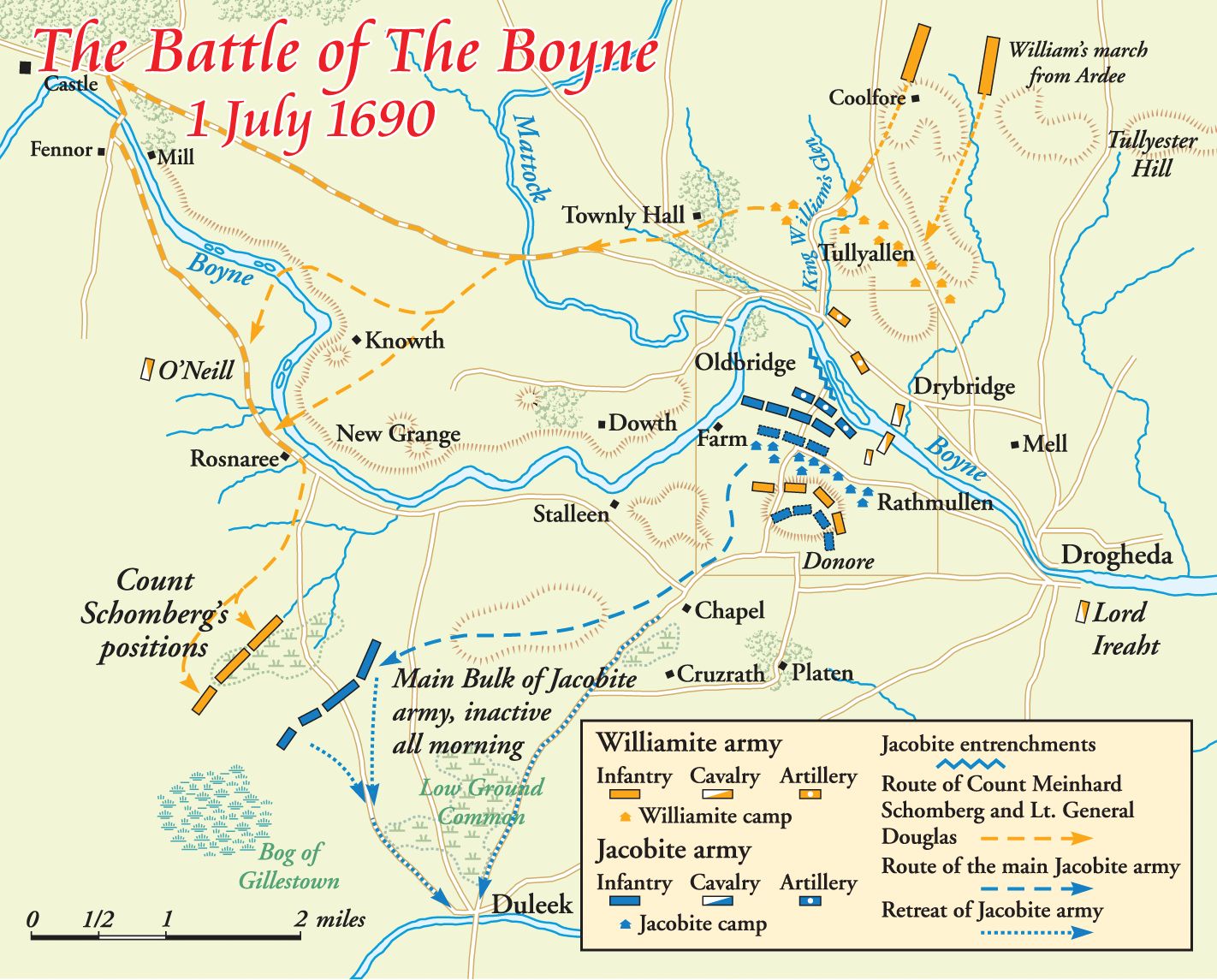

Deposed Catholic King James II had come to Ireland with hopes of regaining the throne of England, and after a year of minor successes and setbacks, the time had come for him to make a stand. An army of 36,000 had gathered in Ulster under William of Orange, William III of England, and they were marching south. James’ army camped on the Hill of Donore, on the south side of the Boyne River, about 30 miles north of Dublin. His troops, mostly raw militia with a few French regiments and artillery, were deployed along the river, occupying and fortifying the bridge at Oldbridge on the left, and the town of Drogheda on the right.

On the morning of June 30, 1690, William arrived at the north bank of the Boyne and immediately sent dragoons and cavalry west to check the bridge at Slane. Directly ahead, he sent the Dutch Guard to scout Oldbridge. As his best infantry units made their way down the open forward slope, French artillery fired on them, and they took casualties before they were recalled.

William then rode down to the river to see for himself. Convinced it could be crossed, he and his staff decided to have lunch in full view of the Jacobites. Two small cannons, hurriedly brought up to within range, fired on William and his party as they mounted to leave. The first shot exploded, killing one man and several horses. The second ricocheted off the ground and hit William in the shoulder.

Rumors of William’s death ripped through both armies and even later reached Paris, where the guns of the Bastille fired a salute, and mobs burned effigies of William and his queen. But the wound was minor, and after having it dressed, he rode through the camps to be seen by his cheering troops. When he returned to his headquarters, he called a council of war. Clear to those on both sides, the Battle of the Boyne on the morrow would definitively decide the fate of the English crown.

The sequence of events that placed these contenders for the throne of England staring at each other across an Irish river began five years earlier on February 6, 1685, when King Charles II died without an heir.

The crown devolved to his younger brother James, who became King James II. A Catholic in a largely Protestant country, James II faced a rebellion almost immediately. James Scott, an illegitimate son of Charles, declared his uncle James’s coronation invalid due to his Catholicism. On July 6, 1685, the Battle of Sedgemoor broke the rebellion, and James Scott, captured at the battle, was beheaded on Tower Hill.

From the early 1670s, the Catholic King Louis XIV of France had been entangled in wars in Western Europe with numerous, mainly Protestant, Allied armies. William, Prince of Orange, was the leader of the United Dutch Provinces, a Protestant merchant state and one of Louis’ major opponents. Stadtholder (chief magistrate) of several of the Dutch provinces, William led a major coalition including Austria-Hungary, Brandenburg, Spain, and Sweden against Louis and his expansionist policies.

James II’s eldest daughter Mary, heir to the throne, married his nephew, William of Orange, in 1677. James II opposed this union, but King Charles II had arranged the marriage because Mary, a Protestant, countered any claims of Catholic subversion. But the 1688 birth of James’s son, James Francis Edward Stuart, Prince of Wales and Duke of Berwick, removed Mary from the line of succession.

To make his claim to the throne secure, William decided to invade England. James II abandoned London, and William and his wife marched triumphantly in with their troops. Even though he was not English, the Londoners received him enthusiastically. They crowned Queen Mary II and King William III as joint rulers. With his countrymen favoring William, James lost his nerve and sailed to France, accompanied by his son, never to see England again.

In Ireland, the Catholic population favored James II, believing he would decree programs favorable to them. Col. Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnell, transformed the Irish Catholic army—promoting chiefly Irish officers, most bound to him by marriage or friendship. Having raised the core of a Jacobite army, he requested James II come to Ireland to take charge in a war against William. At the urging of Louis XIV—who was pleased to be able to distract William from campaigning against him in Europe—James II and a cadre of French officers landed at Kinsale on March 12, 1689, to take command of the Irish Catholic army.

In April James led his army, with Jacobite and French officers, north from Dublin to the port city of Derry (now Londonderry)—a center of Williamite resistance in Ulster, the mostly Protestant part of Northern Ireland. His plan was to capture Derry, secure Ulster, and sail for Scotland, the next step on his path back to the English throne.

James stood before the gates of Derry on April 18 and demanded its surrender. Just five days earlier John Graham, Viscount Dundee, had raised the Scottish Royal Standard on Dundee Law (a hill overlooking the city of Dundee, Scotland) in support of his king, country and the Jacobite cause. For a moment, the way forward seemed clear, the future bright.

But the Williamites inside the walled city of Derry refused, and after unsuccessful attempts to take it, the Jacobites decided to starve them out.

They ran a boom across the River Foyle to prevent Protestant ships from supplying the city and the siege of Derry, the first real military action of the Williamite War, had begun.

The siege lasted 105 days (April 18-August 1) until Major-General Percy Kirke with the HMS Dartmouth and three merchant ships broke through the blockade on July 28.

During that time, William officially declared war on France on May 7 and in July named Friedrich Hermann, Duke of Schomberg, as the commander of an expeditionary force to drive James II out of Ireland.

July was a disastrous month for the Jacobite cause. The loss at Derry came a day after “Bonnie Dundee”was killed at the Battle of Killiecrankie on July 27th and the movement in Scotland faded. On the final day of the month, 1,500 men were killed in a losing cause at the Battle of Newtownbutler near Enniskillen, in western Ulster.

Less than two weeks later, on August 13, 1689, Schomberg landed at Belfast with a Williamite force of 20,000. The news of Schomberg’s arrival prompted James to call for militia from across the land and to prepare to defend Dublin.

A veteran of many European wars, Schomberg, 75, wasted little time in attacking the Jacobite stronghold of Carrickfergus on August 20. The city fell eight days later. It was his hope to take Dublin before winter set in.

As they marched south, Schomberg found that on their retreat to Dublin, the Jacobites had taken crops and livestock and burned what they couldn’t use.

At Dundalk, about 50 miles north of Dublin, the Williamites set up camp. With a force made up of green troops that were outnumbered by the Jacobites, Schomberg declined to engage, staying within his entrenchments. The Jacobites, who came north to taunt them into fighting, took the inactivity as a sign of weakness.

But it may have been more than just Schomberg’s reluctance. Before moving to winter quarters in Ulster, nearly 6,000 Williamites died from lack of supplies and medicine as well as from exposure.

In April 1690, Louis XIV sent 6,000 French regulars and some artillery in exchange for 5,000 Irish infantrymen.

Not satisfied with Schomberg’s lack of progress, William decided to come to Ireland himself, landing at Belfast on June 14, 1690. In addition to English, Scottish, and Protestant Irish Enniskillen troops, his army consisted of a great many Dutch, Danish mercenaries, and French Huguenots. They were armed with the latest flintlock rifles, with socket bayonets, carbines, and pistols.

James’s French-Irish, on the other hand, were armed with inferior matchlocks and pikes. Many of the Irish carried half-pikes, with scythe blades bolted parallel to the ends, probably more deadly than regular pikes. Some infantry carried farm implements, and a few were unarmed. The Irish and French infantry fought in “pike and shotte” formations of an earlier time. Poorly trained and armed, the Irish infantry mainly consisted of peasants. The landed gentry that made up the cavalry, on the other hand, proved to be first-rate.

Antonin Nompar de Lauzun, an advisor to James II and commander of the French troops, counseled him to use the Boyne River against William as a natural barrier.

After William’s picnic stunt—when all was nearly over before it began—his council of war decided to strike on James’ far left, at the Slane bridge. From there, they thought they could cut off the Jacobite line of retreat.

The French-Irish forces numbered approximately 24,000 men. The Williamite Allied army outnumbered the Jacobites significantly, with nearly 36,000 soldiers. Though James’ advisors counseled a retreat, he decided to make a token show before withdrawing. The longer he could delay William in Ireland, the weaker he felt William’s hold on the English throne would be.

On July 1, a little before 5 a.m., nearly 7,000 troops under the Duke of Schomberg’s son, 49-year-old Meinhard, Count Schomberg, marched west to outflank the Jacobite left. A deep fog covered their movement, and upon discovering the bridge at Slane destroyed, they decided to ford the river at Rosnaree, closer to the main Allied position.

James had stationed Sir Neill O’Neill’s Irish dragoons, among the best of the Jacobite horse, to protect the ford. O’Neill had his men dismount, with every 11th man as a horse holder, and led his mere 480 troopers down from the heights to dispute the crossing. Count Schomberg ordered his strongest regiment, the Dutch Guard Dragoons, to charge into the water. The Count “plunged into the river, sword in hand, at the head of the dragoons,” reported Sir Felix, his aide.

O’Neill’s Irish troops opened fire with their carbines, disordering the Dutch dragoons, forcing them to withdraw. Schomberg, unable to force a crossing, ordered his men to dismount and exchange fire with O’Neill. Things settled down to a halfhearted skirmish, which seemed to be in O’Neill’s favor because it would allow time for reinforcements to arrive.

Count Schomberg regained the momentum when he brought his artillery into action and a round shot shattered O’Neill’s thigh, mortally wounding him. As he was carried from the field, his dragoons became disheartened, climbed on their horses, and yielded the ford to the Williamites, illustrating a weakness of the Irish in James’ army—loyal to their clan chief, not their king, meant they would only fight so long as their chief commanded them. Though outnumbered, O’Neill’s dragoons had held the Count in check for more than an hour. Now the Williamite horse crossed the river and formed up on the other side to secure their position.

Meinhard Schomberg sent a report to William via Sir Felix, who became rattled. The shaky account of the battle led William to conclude that James had sent much of his army to reinforce O’Neill. William ordered Lt. Gen. James Douglas to take 12,000 men, leaving only a third of his army, to aid Schomberg.

With his left flank broken, James concluded the time had come to pull out. He ordered his baggage train to begin the withdrawal southward toward the bridge at Duleek. Before beginning his retreat, he ordered a large contingent of infantry and cavalry, along with all his artillery, to Rosnaree, to protect that flank. There were now only about 7,000 men left to confront William III near Oldbridge.

Neither of the two kings realized they had no reason to send their reinforcements to that flank. A deep ravine, with a small ditch at the bottom, protected it. Hedgerows capped the tops of the ravine and this bocage presented a formidable obstacle to anyone attempting to cross. The two relief columns faced each other across this ravine, exchanging sporadic small arms and artillery fire, a situation neither leader was aware of.

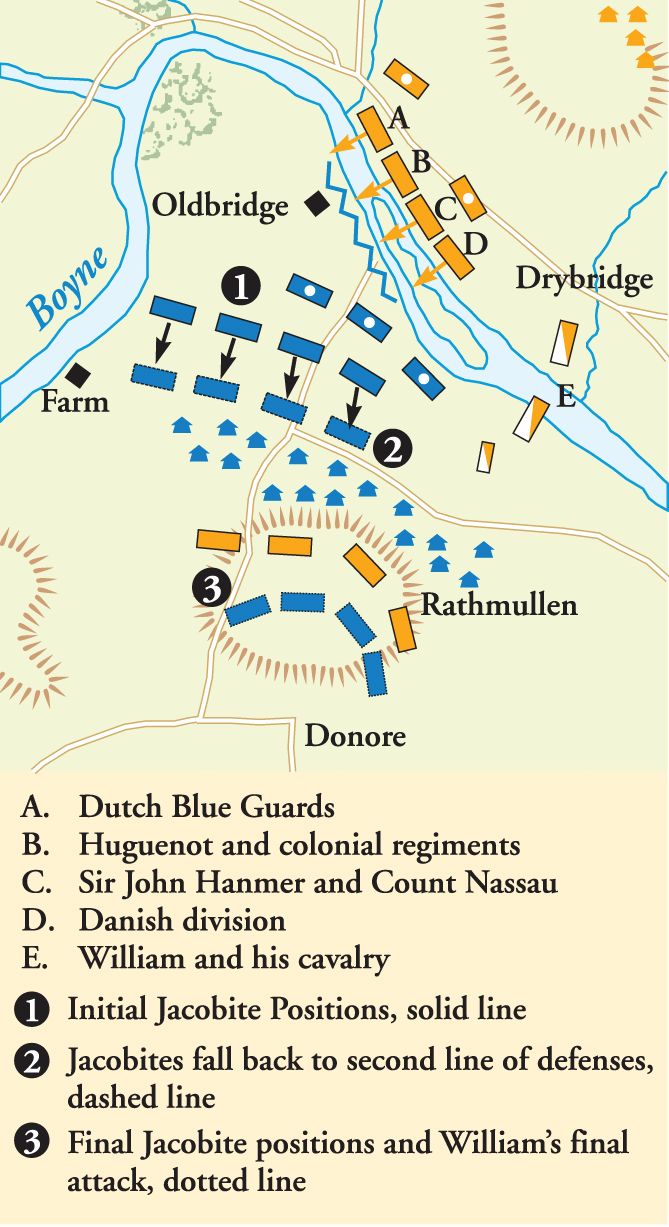

After James sent his left toward Rosnaree, he shifted his main body to the left to cover a possible crossing of the Boyne at Oldbridge, which he considered his most vulnerable spot. He ordered Tyrconnell to watch the enemy across from Oldbridge as the Williamite artillery had started a barrage of the Jacobite positions there. After an hour, the Dutch Foot Guards (or Blue Guards), led by their grenadier companies, attacked. An Irish infantry battalion, in an entrenched position under the Earl of Clanricarde, disputed their crossing. Williamite artillery softened them up before the infantry attack.

“The English artillery played furiously upon the Irish trench, beat it down in several places and killed some men in it,”remembered a member of the Blue Guards.

The Guards plunged into the river, under the fire of the Jacobites. “The enemy did not fire until our men were towards the middle of the river, and then a whole peal of shot came from the hedges, breastworks, houses and all about,” the Blue Guard continued. “Despite the fire, which sounded severe, only two men were hit.”

The three Guards battalions spread out to take Clanricarde’s battalion on both flanks. Slowly, the Guards forced them back, sometimes at bayonet point. The Irish, with their matchlock muskets, stood no chance against the Williamite flintlocks and socket bayonets. The Guards had a rate of fire three times that of the Irish. While the Jacobite army had two musketeers to every pikeman, socket bayonets made each Williamite soldier a pikeman and musketeer.

East of Oldbridge, three battalions of Jacobite foot deployed to dispute other fords at Grove and Yellow Islands. James ordered two of those battalions, both Irish Guards, to counterattack the Dutch Guards, leaving only one battalion to cover the two islands. During the attack, Major Thomas Arthur, the commander of the 1st Irish Guards, “ran the [enemy] officer through the body that commanded the Battalion he marched up to, before sustaining a mortal wound.”

Initially, the opposing Guards battalions engaged in a hand-to-hand battle but both sides eventually fell back to within musket range, with Clanricarde’s battalion falling in on the left of the Irish Guards. The Irish stood no chance against the disciplined volley fire of the Dutch Guard. With the Dutch slowly pushing them back, the Irish fired as they retreated, refusing to give in completely. It took half an hour of heavy combat, but the Dutch Guards cleared Oldbridge and secured their position.

Jean-François de Morsier, a Swiss Protestant serving with the Blue Guards described the desperate fighting that took place. “We fell on them, as much with musket fire as with bayonets, and drove them off. Our French battalions and others followed us close while the King had a battery of cannons fire on the enemy army.”

As the Guards battalions engaged at Oldbridge, the leading regiment of the Williamite Huguenot brigade crossed the river at the Grove Island ford. By this time, the tide was in and the Boyne was much harder to cross. A Jacobite counterattack faltered, and the men retreated to the top of the ridgeline south of the Boyne, where their officers struggled to get them moving again.

By 11:30 a.m., the Jacobite situation was quickly deteriorating. Clanricarde had been pushed from the Oldbridge crossing by the Dutch Guards and a single regiment of infantry under the Earl of Antrim held the south bank of the Boyne. More and more Williamite troops moved into the water to cross the river. James sent his two best regiments of cavalry against the Dutch Guards, now east of Oldbidge and reforming. The Irish Life Guards and Tyrconnell’s regiment galloped down the hill toward the Dutch, who opened fire as they approached. The close-range volley took down many horses and troopers. Disordered, the Jacobite cavalry retreated to the top of the ridge to regroup.

Now at almost noon, the Duke of Schomberg began to cross the river at the head of three Huguenot infantry regiments, who were wallowing in the waist-deep water. Holding their muskets and ammunition over their heads, they slowly made their way across. A brigade of Northern Irish Protestants, unable to cross behind the Huguenots, moved upstream to cross at Oldbridge. Antrim’s regiment fired a few volleys, but it had little effect on the oncoming Allied infantry. William’s Anglo-Dutch and Danish brigades extended beyond Antrim’s right, and they retreated.

The Duke of Schomberg halted on the southern side of the river, allowing time for Lt. Gen. James Douglas’s five battalions to join Schomberg’s formation. This attacking force numbered about 11,000 men. But more Jacobite troops arrived to increase the number of men against Schomberg.

On the right flank of the Williamite advance, where Count Meinhard Schomberg commanded, the stalemate continued. Meinhard ordered his dragoons to dismount and attack the Jacobite troops. He soon found the boggy ditch at the bottom of the ravine dividing the two sides would be impossible to charge across. Meinhard shifted to the right, looking for a way around the ravine. This posed a danger to James’ flank and rear, forcing the Jacobites to shift to their left.

Following the failed charge against the Duke of Schomberg’s men at Oldbridge, the Irish Life Guards and Tyrconnell’s regiment, reinforced by another cavalry regiment, rallied to charge downhill towards the English, Huguenot, and Danish regiments struggling to climb the southern ridge. They crashed into the lead regiments of Sir John Hanmer’s English infantry and Huguenots under the command of Pierre Massue de Ruvigny, sieur de la Caillemotte.

Approximately 40 riders broke through Hanmer’s regiment as the infantry threw themselves aside to escape the flashing sabers, and the cavalry only killed three. A shot mortally wounded Caillemotte in the chest. As his men carried him off the field, he attempted to rally his soldiers, yelling to them, “To glory, boys! to glory.”

As the Irish cavalry retreated again to regroup, Schomberg tried to rally the Huguenots. He pointed across the river to the Jacobite cavalry and shouted, “Let’s go men, there are your persecutors.” As he and his aides crossed the river, they soon found themselves surrounded by about 40 Irish troopers.

“The Duke of Schomberg who was recognized from his blue ribbon (the Order of the Garter) received two saber wounds on the head at the same time that he was shot in the neck by a carbine wound,” de Morsier wrote. “The shot threw the duke from his horse.”

The Reverend George Walker, who had been mayor of Londonderry during the siege, had attached himself to Caillemotte’s regiment. Now, as he moved to aid the fallen Schomberg, Walker was fatally shot in the stomach by a Jacobite horseman. When he later heard of Walker’s death, William exclaimed, “The fool! What business had he there?”

The Jacobite horse swept into Colonel St. John’s infantry as they changed from column into line. They cut many of the hapless soldiers down before reining in and returning to their initial position to reform. Some of the troopers, unable to halt their mounts, continued through the Williamites, who encircled and killed them. The cavalry reformed for another charge, this time against the Dutch Guards.

William stood watching the Irish cavalry as they bore down on his favorite unit. “The musketry covered us in such a dense pall of smoke that the King, on the ridge, could not see us and said ‘My regiment is entirely beaten!’” related de Morsier, “And an instant later when the smoke cleared he exclaimed ‘Thank God, I see them again!’” George Clarke, Secretary of State for War, stated the king “said he had seen his guards do that which he had never seen foot do in his life.” Again, the Guards’ disciplined volley fire stopped the Irish cold. A few of the horsemen closed to pistol shot range but then the Jacobite cavalry retreated.

With most of the Irish infantry retreating, and their cavalry occupied with their engagement with the Huguenot brigade, few Irish defended the Yellow Island ford. Danish troops under Ferdinand Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg-Neuenstadt, crossed almost unopposed by Irish troops. The Boyne itself, with deep water and unstable bottom, contested the crossing though, and the Danish foot soldiers feared drowning. Led by their grenadiers and King Christian’s Foot Guards, they eventually crossed the river, holding their muskets and ammunition above their heads. They formed a shaky bridgehead on the southern bank of the river.

Tyrconnell sent two fresh regiments of dragoons, under Walter, Lord Dongan and Charles O’Brien, Viscount Clare, against the Danes. The dragoons did not dismount for their attack but charged on horseback. A Danish volley drove off O’Brien but Dongan attacked a regiment of Danish cavalry and dispersed them. The Danes fled back across the Boyne. Unfortunately, as Dongan’s troopers moved back to the top of the hill to rally for another charge, a Danish musket ball struck and killed Dongan.

As O’Niell’s men had done at Rosnaree, both Dongan’s Irish regiments lost their will with his death and—despite the fact they had successfully pinned the Danish infantry against the riverbank—fled toward Duleek.

With the attack in the center at a standstill, William decided to move to his left and cross at Mill Ford and come in on the Jacobite right flank. He ordered his cavalry across first and Lt. Gen. Baron Ginkel’s brigade led the way, brushing aside an Irish picket post. Three more cavalry regiments and three regiments of dragoons followed with no problem. But the horses had churned up the mud in the riverbed so much, it became impossible for the infantry to cross. William ordered them to seek out another crossing upstream, and then set out to cross the river himself.

The king’s horse soon foundered and he dismounted to lead him across. Halfway, William suffered a dangerous asthma attack and might have drowned but for an Enniskillen trooper named McKinlay, who dragged William and his horse to safety. William’s crossing of the Boyne and the turning of the Jacobite right flank spelled the end of the battle for the Jacobite army—they retreated toward the bridge over the Nanny River at Duleek. An Irish chronicler described the English crossing at Mill Ford as the place where “the one hope of Mother Ireland died.” Led by de Lauzun’s Frenchmen, the French-Irish marched off to Duleek, in the rear of the Jacobite army. The bridge at Duleek, over the Nanny River, created a bottleneck, but the Jacobites’ communications with Dublin depended on holding it.

William’s cavalry used their carbines to shoot at the French and Irish column. The Jacobites, fearing they were caught in an enemy pincer movement, began to unravel.

Before reaching Duleek, the road is controlled by Donore graveyard. A walled area on a steep hill, the graveyard formed a natural ambush position where a Jacobite rearguard could hopefully delay the Williamite pursuit long enough for the Irish and French to escape. Dismounted cavalry and dragoons established a defensive line behind the graveyard walls.

The Allied cavalry under Ginkel and William led the pursuit. When they came close to the graveyard, they rode into a heavy fire from behind the wall, and soon the two forces intermingled in a savage melée. Many times, in the smoke and confusion of the battle, one of the two sides mistook a unit of their own side for the enemy. The Protestant Irish Enniskillen cavalry, serving with the Williamites, charged against the Danish cavalry. With the Danes uniformed in white, the Protestant Irish mistook them for a Jacobite regiment since most of the Allies wore red. William himself barely escaped death when an Enniskillen trooper aimed a pistol at him, being stopped just in time.

Ginkel tried to outflank the right of the Jacobite cavalry, but an Irish cavalry squadron forced them back. As the horsemen struggled in a fierce clash, a unit of English dragoons, who had taken position behind some hedgerows, fired into the crowded mass. The more men William threw into the confused fighting, the more muddled the fighting became. William’s force that had crossed the Boyne at Mill Ford lost approximately 150 men before they could disengage and bypass the graveyard.

The Allied pursuit continued, chasing the French-Irish and trying to engage the Jacobite main force before they reached Duleek. The Irish made a last ditch stand at a walled field near Platin Hall. A narrow sunken lane, the only entrance to the hall, ran along its western flank. In the lead, Enniskillen horse commander Col. William Wolseley gave the order to wheel to the left. This mistaken order caused the Protestant Irish to offer their rear to the waiting Jacobite Catholic Irish. Wolseley quickly attempted to reverse the order. He “cried aloud to them to wheel to the right on which some wheeling to the left and some to the right, they ran into great disorder and confusion,” as described by an eyewitness, John Richardson. The waiting Jacobite horse, under Lt. Gen. Richard Hamilton, charged into Wolseley’s cavalry, and they “routed and killed about fifty of them on the spot.”

Hamilton outplayed his success by pursuing Wolseley until he ran into the main body of the Allied horse under William. The Irish Catholics, severely outnumbered, were crushed, and Hamilton was captured. Taken before the king, William asked him if he thought the French-Irish would stand again before Duleek. “Upon my Honour, I believe they will,” Hamilton replied. “Your Honour? Upon your Honour?” William said mockingly, and ordered Hamilton led away.

As the French-Irish army retreated toward Duleek, many left the ranks, in a panic to reach the bridge before the Allied cavalry overtook them. The officers gathered around James, but they found nothing but confusion—he had no orders to give except to get to Duleek as fast as possible. At this time, the Jacobites believed Tyrconnell to be holding out at Oldbridge. When they received word that he had been defeated and retreating, De Lauzun feared for James’ life. He ordered two regiments, cavalry, and dragoons, to escort James from the field.

This reduced the Jacobite horse to just two regiments of cavalry and two regiments of dragoons. With their depleted horse, it would be impossible to stop the Williamite horse, which greatly outnumbered them. This left the French-Irish with their only choice—make for the Magdalene Bridge over the River Nanny with all possible speed.

The road was a scene of mass disorder as the Jacobite soldiers, some mounted and some dismounted, tried to outdistance the Williamite horse. Many had thrown away their muskets, and some even their coats and shoes, to give them more speed in their flight. To make matters even worse, some of the retreating men broke open barrels of whiskey and became raucously drunk. The retreating French artillery found itself overrun by a routed unit of Irish dragoons. An Irish dragoon commander, Charles O’Brien, rallied a few dozen men and they escorted the French guns all the way to Limerick.

The French commander de Lauzun kept his men together and they reached Duleek without a fight—until friendly cavalry, fleeing from Platin Hall, rode into the French “in Duleek Lane, enclosed with high banks, marching ten in rank.” The Irish horse “broke the whole line of foot, riding over all our battalions,” said John Stevens, a French brigade officer. “The horse came on so unexpected and at such speed, some firing their pistols, that we had no time to receive them, but all … took to their heels, no officer being able to stop the men after they were broken.”

Having been bloodied twice, at Donore and Platin Hall, William’s force lacked the strength to continue an organized pursuit. Count Schomberg on the extreme Allied right, was also unable to mount an attack on the routed Jacobites. The Williamites at Oldbridge, after three hours of furious combat, reorganized and the reserve infantry crossed the Boyne. Consequently, the Allies were no longer able to mount a pursuit. The fleeing Jacobites did not know this and struggled to pass through the bottleneck at Magdalene Bridge.

The old stone arch bridge was only wide enough for six men abreast and the shoreline, steep and swampy on both sides of it, made fording impossible. The still organized cavalry stood in a position to hold off any pursuing troops and de Lauzun managed to consolidate the men to cross through the choke point. By about 5 p.m., the last of the Jacobite army had shuffled across.

The French brigade took up the rearguard position south of the bridge and Schomberg pressed them so hard they had to stop and deploy to secure the road. They slowly engaged in a fighting withdrawal for approximately three miles until they reached another river, the Naul. Tyrconnell gathered several infantry battalions and some cavalry on the south bank of the river to support the French as they crossed. The two sides faced each other until around 10 p.m., when William sent word to Schomberg to call off the pursuit.

Rumors had been reaching Dublin about the defeat, mainly fueled by the arrival of stragglers from the Jacobite cavalry. When James and his escort reached Dublin Castle, the Dubliners knew the rumors to be true. James felt, unjustifiably, that his defeat came about because of his Irish troops. “When it came to a trial they hastily fled the field, … nor could they be prevailed upon to rally,” he ranted.

Early the next morning, James left Dublin, heading toward Duncannon Fort where he boarded a French frigate to Kinsale. From there, he took a ship to France and went into exile, never to return to Ireland or England. This secured the English throne for Mary II and William III.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments