By Christopher Miskimon

A rocky, jumbled mass of boulders known as Mount Harriet just west of the city of Stanley in the Falkland Islands had no claim to fame before the night of June 11-12, 1982, but it achieved renown after a harrowing engagement that occurred between British and Argentine forces that night.

After nightfall, British Royal Marines crept cautiously uphill against defending Argentine soldiers. When Corporal Steven Newland learned his platoon was pinned down by a sniper farther up the hill, he decided to do something about it. Newland and a mate, Chris Shepherd, crawled forward to flank the sniper. As they moved, incoming fire spattered on the rocks around them. Newland had good cover so he kept going. Shepherd had no such protection and was forced to lie prone.

Crawling through the rocks, Newland found the sniper, but the Argentine was not alone. A whole squad was lying in wait, 10 men with rifles and a machine gun. One of them would shoot occasionally. Newland thought the enemy squad was hoping the British would try to rush the sniper only to be cut down by the machine gun and supporting riflemen. He resolved to do something but realized then Shepherd was not there; he was alone. Nevertheless, Newland took action.

The young corporal put a fresh magazine in his rifle, turned the safety off, and drew two grenades from their pouches. He hurled the grenades at the enemy machine-gun position. One landed right on the machine gun and the other among the enemy soldiers. Newland ducked behind a rock and waited until he heard two explosions. “As soon as they’d gone off I went in and anything that moved got three rounds.… I don’t know how many I shot but they got a whole mag,” he wrote. He reloaded and was about to see if anyone was still alive when a squad mate called on the radio and told him they were going to fire two 66mm rockets into the position. Newland quickly took cover.

The rockets slammed into the enemy location, and Newland collected any prisoners to prevent them from escaping. He took a different path back and saw an Argentine he had shot earlier. The man had fallen but apparently was only wounded. As Newland came close, the enemy soldier fired a burst, striking the corporal in both legs. He felt the bullets hitting his legs and went into a rage. Before the soldier could finish him, Newland had shot the man 15 times in the head.

The final battles of the Falklands War were often confused, swirling melees of desperate close combat. The British force, trying to liberate the islands from an Argentine seizure, did not have a particular advantage in numbers or firepower. What made the difference was the level of training, élan, and discipline that has hallmarked the British soldier throughout the 20th century. This was the factor that brought British armor to success in the South Atlantic.

The argument between Argentina and Great Britain for possession of the islands came to a head in 1982. Argentina, under new rule after a coup d’état, perceived a number of British actions as signals that their desire to keep the islands was fading. The Home Office decided the Falkland Islanders were no longer guaranteed automatic British citizenship under the 1981 Nationality Act. The government was also withdrawing the artic protection vessel Endurance from the area without replacement. Also, the United Kingdom announced it was considering scrapping or selling much of its surface fleet. Together, these occurrences seemed to indicate the United Kingdom was withdrawing from the region and with a reduced fleet, would be unable to defend the Falklands anyway. An Argentine task force sailed to take the Falklands on March 28, 1982, quickly seizing control. Great Britain decided to retake the islands and responded with a fleet and amphibious force. By May 21, British troops were ashore and fighting their way toward Stanley, the Falklands’ largest settlement.

On June 10, British troops were in place to assault the Argentine defenses surrounding Port Stanley. The defenders placed a mix of marines and army troops on various hills west of the town. They were supported by artillery and equipped with heavy machine guns and antiaircraft weapons. A smaller number of troops were deployed around the peninsula Stanley occupied to guard against amphibious and special forces attacks.

The British arrayed their forces on a line of hills west of the Argentine positions, effectively trapping them around Stanley. From a prisoner, the British obtained a map outlining the Argentine defenses. Thirty 105mm guns of the Royal Artillery were painstakingly moved within range and 500 rounds per gun stockpiled. On the night of June 10, British 3 Commando Brigade, composed of the 40,42, and 45 Royal Marine Commandos and reinforced by 2 and 3 Parachute Regiments, would attack from the west. On the following night, 5 Infantry Brigade, made up of the 2 Scots Guards, 1 Welsh Guards, and 1st Battalion, 7th Gurkha Rifles would attack toward Stanley from the southwest, a more obvious route for attack given the terrain.

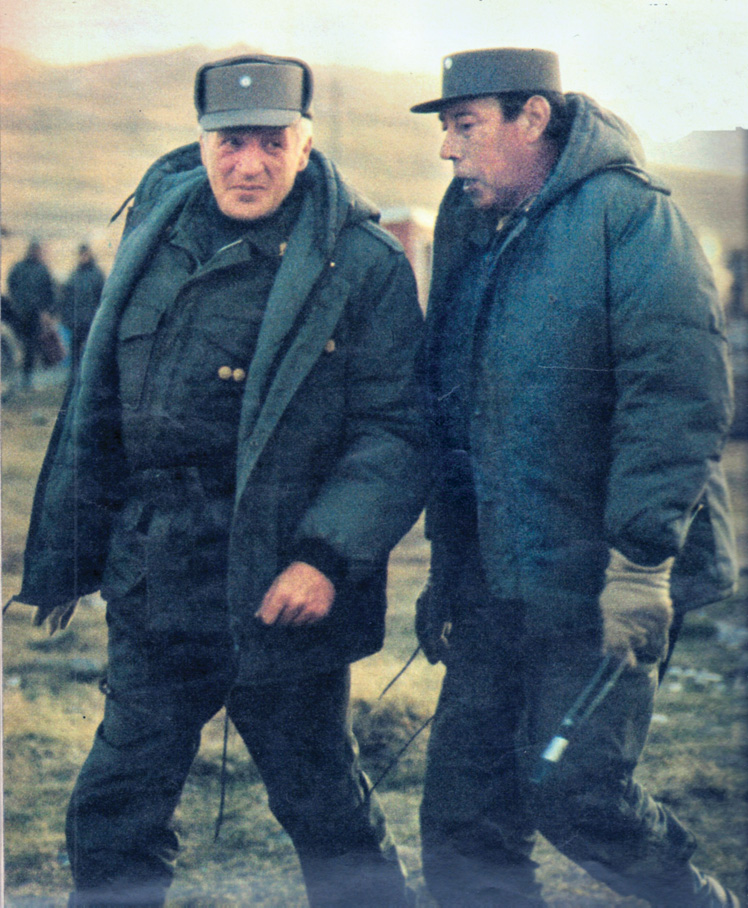

The Argentine commander, Brig. Gen. Mario B. Menendez, expected the British to come from the southwestern route. The Argentine high command wanted him to attack, but given that the army was made up largely of conscripts Menendez wisely chose to stay on the defensive. There were about 9,000 Argentine troops around Stanley. Of these, 5,000 were actual combat troops. Menendez placed the 3rd, 6th, and 25th Regiments along the coast. Inland, the 5th Marines were dug in on Sapper Hill, Mount Wilson, and Mount Tumbledown. The 4th Regiment was centered on Mount Harriet and Two Sisters. These points of high ground covered the approaches from the southwest. Guarding the west and northwest lines was the 7th Regiment on Wireless Ridge and Mount Longdon. These troops were exposed to the cold and wet, while the support troops in Stanley lived more comfortably. Their logistical system functioned poorly; many rear-echelon troops made money selling rations and comfort items to the infantry when the transportation network failed to deliver them.

While both sides prepared for the coming fight, the British kept up a constant harassment of the Argentine positions. Royal Navy warships joined the Royal Artillery in nighttime bombardments throughout their enemy’s positions, causing few casualties but taking a psychological toll. Each night British patrols crept among Argentine units, collecting intelligence and ambushing any Argentine soldiers who dared move in the darkness. Still, morale held and the conscripts remained in their positions.

The British artillery and aircraft kept up a steady pounding. Ships offshore continued nightly firing, but the Argentines considered naval gunfire less effective than field artillery.

Argentine troops on Mount Harriet watched British helicopters deliver howitzers to their firing points. Once in place, the guns began daytime firing, something the defenders previously had not faced.

In the air, Harrier jets conducted air strikes that terrified the Argentine conscripts. They were hastily issued newly acquired Soviet SAM-7 shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles to counter the threat. The troops immediately put these new weapons to use but had little success since there was no time to train them. An Argentine officer on the Two Sisters hill recalled watching two Harriers attack on June 5. Both escaped because the SAM-7 operators had not sighted properly. Four days later a corporal fired on another Harrier, but the missile landed next to one of their own fighting positions. The officer noted the sergeant in charge of the SAMs seemed under “psychological difficulty,” so he took charge of the section himself. While he hoped the Harriers would make another attack, the officer noticed that his troops seemed shaky. “I hope there will not be great failings when we really have to fight,” he wrote.

In the days before the Battle of Stanley, 17 Argentine soldiers were killed by artillery and air attacks. Many wounded were sent for treatment aboard converted hospital ships berthed in Stanley Harbor. A sailor aboard one of them recalled most of the wounds were caused by artillery fire. The number of wounded failed to dent Argentine morale, which was still good. Though there was deprivation for the troops in the hills, they felt ready for the British onslaught. The Argentines were dug in behind minefields, and they were prepared to use artillery and machine guns in the open terrain in front of their positions. Menendez issued a statement urging his troops to destroy the British, avenge the sacrifice of their fallen, and beat the enemy so they “will never again have the impertinence to invade our land.” To the west, the British arranged to make Menendez’s words ring hollow.

On June 11, the British attacks began. The first was an attempt to kill Menendez. It was believed he held a conference in Stanley’s town hall each morning. That day a Wessex helicopter three miles north of the building fired two AS-12 missiles in the hopes of decapitating the enemy leadership. The first missile malfunctioned; the second sailed past the target and struck the nearby police station. Luckily there were no casualties; a message warning the locals to stay away did not reach them. After nightfall the first phase of the ground assault began. Mount Longdon would be attacked first by 3 Parachute, a short time later 45 Commando would strike Two Sisters, and 42 Commando would take Mount Harriet.

Mount Longdon is a mile-long, east-west hill with steep slopes averaging 300 feet above the surrounding ground. The area was occupied by the Argentine 7th Regiment, which held most of the line on the northern side stretching back toward Stanley. Company B sat atop Mount Longdon along with a platoon of attached engineers. A number of .50-caliber machine guns completed the defense. The Argentine position formed the northwestern corner of the entire Stanley defense, with two platoons oriented north and one west, engineers in reserve.

The British plan called for one company of 3 Parachute to seize a hill 500 yards north of Mount Longdon and use it as a base of fire while a second company attacked from the west and rolled up the enemy by moving eastward. To do this they had to cross five miles of open ground against defenses they were only partly able to discern. Nevertheless, by 9:15 pm the two attacking companies were at their starting point, a stream a half mile from the foot of the hill. There would be no artillery preparation; they would close the distance in silence. Luckily, Argentine radar capable of detecting troops on the ground was not operating. An officer ordered it turned off that night, concerned its emissions would draw artillery fire. British attacks were expected to happen in daylight or just before dawn.

Company A moved to occupy the hill while Company B attacked Mount Longdon itself. They got halfway to their objectives before an unlucky British soldier stepped on a land mine. The explosion brought heavy fire as the British rushed to close the remaining distance. Company A found its hilltop objective well covered by enemy machine guns and mortars, and it was driven off. Company B quickly became pinned down in several gulleys on the west slope of the hill. For several hours the fight raged as the parachute troops slowly moved forward in tiny rushes and bursts of fire. The Argentines handled their machine guns well, taking a fearful toll on the British. Argentine mortars fired constantly until British artillery bombarded the eastern end of the hill, silencing them permanently. At one point the parachute troops fell back and directed the artillery to walk their fire back to the west, softening the enemy positions for another assault.

Color Sergeant Brian Faulkner, a medic, hurried forward with extra weapons and ammunition before returning to his medical duties. When a man became wounded, his mates gave first aid and stuck his rifle into the dirt to mark him for the medics. Faulkner helped a corporal who had lost one leg and part of another. Even in the dark he could see the paratrooper’s paleness from blood loss. Despite his injuries, the man was focused on his mission. “Get the map … it marks all the positions.”

Lance Corporal Dominic Gray was hit in the head while evacuating wounded. He simply wrapped a dressing on the wound and continued, taking more injured men away to treatment. Only when the battle ended did the young man agree to evacuation. Another British soldier, pinned and unable to move, lay down next to a dead Argentine and made tea.

With Argentine machine-gun fire pinning many of the paratroopers down, Sergeant Ian Mckay saw his platoon commander killed and decided to do something. He called to his soldiers to follow and moved up the hill. All three men who went with him were hit, leaving him alone. McKay went on anyway and silenced several enemy machine-gun nests with a few grenades. In the process, he was killed by enemy fire. His bravery allowed the attack to continue at the cost of his life. McKay would be awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, the only one given for the fighting near Stanley.

Warrant Officer John Weeks moved ahead with Company B, clearing positions with the lead elements. He went into a bunker someone else had already cleared. Inside was a body covered by a blanket. Weeks found it odd. Who would cover a body with a blanket in the middle of a fight? He gave his submachine gun to a corporal and told him to stand watch. When Weeks pulled the blanket away, the Argentine underneath tried to throw a phosphorous grenade. The corporal shot him.

The rest of the night was a blur for the warrant officer. He stripped bodies of ammunition to provide for troops still fighting. He also watched Captain William McCracken fire a 66mm rocket at a particularly stubborn enemy defensive position and also direct artillery fire as close as 25 meters away.

McCracken was a forward observer attached to Company B. He and his signaller crept forward with the infantry calling in barrages, helping the advance. Argentine troops fired on them as they radioed for artillery fire. The artillery silenced a machine gun and several snipers.

Unable to occupy the hill to the north, Company A joined in the attack on Mount Longdon around dawn. The stiff resistance slackened, and the Argentine defense simply collapsed. The British quickly occupied the entire hill and dug in. Throughout the morning, Argentine artillery pounded the parachute troops, but they stubbornly held on. The fighting for Mount Longdon was the heaviest combat of the battle for Stanley. The parachute troops suffered 19 dead and 35 wounded in 10 hours of fighting. Precise Argentine casualties are not known, but at least 29 were killed and 50 captured. Although it was the worst of the fighting, other battles raged that night on nearby hills.

Two Sisters was the second objective of the British assault. Two miles long with twin peaks that give the feature its name, the west peak was 700 feet above the surrounding ground, the east peak a little lower. Each was defended by a company of Argentine soldiers. The west hill had 170 men dug in with mortars and machine guns. The east feature had perhaps 120 troops. Overall, it was an impressive defensive position a mile southwest of Mount Longdon.

British 45 Commando was assigned the mission of taking the hills. The plan was for X Company to take the western hill, emplace heavy weapons, and then support two more companies as they attacked from the north. Those companies would seize the saddle (the low point between the two hills), turn east, and take the eastern hilltop. As it happened, X Company was two hours late getting into position, badly overloaded with extra weapons and ammunition. This meant the two attacks had to go in together rather than one supporting the other.

Captain Ian Gardiner commanded the 150 men of X Company. He spent hours getting his marines reorganized for the attack after they were scattered during the night movement. Their heavy MILAN wire-guided missiles and ammunition made the rough terrain even harder to cross. Much to his relief, his colonel understood the predicament and calmly told him to carry on. Gardiner ordered his troop commanders (a troop is the Royal Marines’ platoon equivalent) to finish their preparations. When everyone was ready, they would go together. Ten minutes later the entire company was ready to move.

The soldiers stepped off with 1 Troop in the lead, 3 Troop following, and 2 Troop in reserve. Unlike Mount Longdon, the going was somewhat better. The leading troop made it halfway up the hill before encountering resistance. Two well-sighted enemy machine guns opened fire. Whenever the marines tried to move up a gully the machine guns chattered or an Argentine soldier fired on them. The rest of the company could not move without taking heavy fire, so Gardiner pulled 1 Troop back a short distance and called for fire support. Unfortunately, since the advance had begun late, the artillery was now busy elsewhere. Supporting mortars ceased fire after eight rounds; their baseplates had disappeared into the soft ground. Gardiner ordered his men to use the MILAN missiles, which proved effective.

Even without support, the attack had to continue, so 2 Troop advanced. To Gardiner, it seemed they were moving through the rubble of a town. Rocks and boulders were strewn everywhere. They made it to the top only to have Argentine artillery pelt them. This wounded one man, X Company’s only casualty of the night. Two Argentine machine guns were quickly knocked out, leaving the marines in control of the hill. The company dug in, awaiting daylight. A few snipers remained, but the British decided to wait for dawn before eradicating them.

On the eastern hill, Y and Z Companies were making their attacks. Second Lieutenant Augusto La Madrid of Argentine B Company, 6th Regiment was on this hill. He watched the fighting at Mount Longdon through binoculars. As he did, a British heavy weapon began firing at Longdon from 400 meters away. La Madrid moved one of his machine guns from its primary position and directed its crew to fire on the enemy.

After this, the British attacked his position on Two Sisters. The Royal Marines flanked the Argentines; La Madrid had no idea what was happening until they were behind him. A .50-caliber machine gun exchanged fire with the marines for a long time. Afterward, La Madrid heard someone shouting orders in English. Orders came to fall back to a position behind Two Sisters. The British marines took the hill tops but advanced no farther, content with shooting at the Argentines. La Madrid received another order to fall back to Mount Tumbledown because the Argentine artillery back in Stanley was about to bombard Two Sisters. This left the British in possession of the entire position.

The battle for Two Sisters was quicker and less bloody than that for Mount Longdon. The Royal Marines lost four dead and 10 wounded. Their opponents lost 420 killed and another 54 taken prisoner with an unknown number of wounded. The Argentine commanding Two Sisters was cashiered after the conflict for his poor handling of the battle. For the British, there was one more action left this night.

More than 300 Argentine soldiers were positioned on Mount Harriet, a mile-long ridge situated one mile south of Two Sisters.

British 42 Commando had spent many days dug in on nearby Mount Kent, and its leaders had used the time wisely, concocting a daring plan to bypass the western defenses. Instead of a frontal assault, two companies would infiltrate through an Argentine minefield, move south of the hill, and flank the Argentines from the south-southeast.

The initial part of the plan went well. A force of 250 marines marched four miles through the darkness, avoided the mines, and reached the starting point for the attack without being discovered. Moving silently, Company K, the leading British force, reached the Argentine reserve force positions before it was detected. A single shot in the darkness set off the battle. For more than an hour the marines fought the conscripts of a reserve infantry platoon and a mortar platoon. In the process, the marines lost about a half dozen men.

Meanwhile, the second British unit, Company L, attacked from the south as Company K wheeled left and attacked the Argentine positions from the rear. Soon the Argentines manning the trenches of Headquarters Defense Platoon, Argentine 3rd Brigade were overrun. The battle, which had lasted about four hours, left the Argentine defenses in a shambles. The Argentines surrendered.

At the same time, Corporal Newland of Company K was making his own attack. Wounded in both legs, he sat down and tried to use his field dressing to stop the bleeding. Realizing no one knew where he was, Newland started walking down the hill. He eventually ran into L Company and was challenged by a sentry. He identified himself and was brought in. Newland waited in the cold and rain for six hours before a helicopter took him to the hospital ship Uganda.

As on the other hills, the battle was winding down by dawn. A lone Argentine sniper held out a while, wounding several men. He was finally killed when the British fired a missile into his position. A few Argentines managed to slip away, but about 250 were taken prisoner and 10 were killed. The British lost one man and suffered 10 others injured. All the British troops were warned to be ready to advance again, but this was wishful thinking and no order ever came. The first phase of the Battle of Stanley was over.

The night of June 11-12 was difficult for the British infantry and disastrous for the Argentines. The entire outer belt of the Stanley defenses was in British hands. Of the 850 Argentine troops previously manning those defenses, 50 were dead and 420 captured. The remainder retreated toward Stanley. British losses amounted to half that many dead and 65 wounded.

Back in Stanley, three civilians died when their shelter was hit by an errant shell from a British warship. An RAF bombing raid on Stanley Airfield caused little damage and no casualties. That night a group of Argentine troops using a makeshift launch ramp fired an Exocet missile at the frigate Glamorgan, striking the ship’s stern and killing 13 sailors. It was the last chance they would get to fire at a British warship.

Rather than immediately continue the attack, the British decided to pause for a day and resume the offensive on the night of Sunday, June 13. The artillery was down to just a few rounds, and it would take a day to restock to a bare minimum of 300 rounds per gun. During the day Argentine Skyhawk aircraft made several ineffective attacks. The final Argentine air attack of the war was by a pair of bombers. They dropped their loads around Mount Kent but did no damage. One bomber was shot down by a missile from the destroyer Exeter.

After nightfall the final moves of the Falklands War took place. The British objectives were three hills: Wireless Ridge, Mount Tumbledown, and Mount William. The soldiers of 5 Infantry Brigade went into action. Tumbledown would be attacked first by 2 Scots Guards. Afterward, 1/7 Gurkhas would seize Mount William. Simultaneously with the Tumbledown attack, 2 Parachute would take Wireless Ridge. Tumbledown and Mount William were protected by the Argentine 5th Marine Battalion. Wireless Ridge was defended by 500 troops of the 12th Regiment, which fought at Mount Longdon. These hills were vital to the defense of Stanley, and without them it would be difficult to defend Argentina’s last bastion in the Falkland Islands.

Yet another rock-strewn ridge, Tumbledown was the first objective. The ridge is narrow, 11/2- miles long, with peaks 750 feet high. It was a key point in the defense as it overlooked open ground. Mount William was almost a feature of Tumbledown, just south of the ridge’s eastern end. The 5th Marines’ Company N sat on Tumbledown and Mount William. Company M sat on Sapper Hill about halfway back to Stanley, while Company O formed the battalion reserve. It was moved to a new position southwest of Mount William in expectation of a British attack from that direction. Battalion Commander Carlos Robacio and Lt. Cmdr. Antonio Pernias, his operations officer, also reinforced Company N and moved their heavy mortars, believing the British had located them. The tactic worked because the British artillery struck empty positions.

The British planned to launch a diversionary attack from the southwest, just where the Argentines had placed Company O. This would be carried out by 30 Scots Guardsmen assembled from excess personnel. The ad-hoc group was supported by engineers to clear mines and four light tanks from 4 Troop of the Blues and Royals. While this diversion held the enemy’s attention, Company G Scots Guards would quietly infiltrate the west end of Tumbledown.

The diversion captured Argentine attention as a brisk firefight developed. Heavy artillery and machine-gun fire fell upon the platoon. Some fighting was close enough for grenades to be thrown. One of the British tanks, avoiding a crater on the trail, struck a mine and had to be abandoned. The rest of the troop lined up on the trail unable to move for fear of more mines. Only one tank could bring its weapons to bear effectively. The platoon commander, Lieutenant Mark Coreth, lost his tank to the mine. He braved artillery fire and led one tank and then another to the front firing position by mounting a tank’s hull and directing it forward. The tanks kept firing until the entire force pulled back, believing its mission complete. Mortar and artillery fire landed nearby, and two men were wounded when they struck another mine. Although the attack did not draw any Argentine reserves, Pernias was convinced this was the British main effort.

On the west end of Tumbledown, G Company’s silent assault paid off. It occupied one-third of the ridge without enemy notice. The next unit, designated Left Flank Company, passed through G Company to take the next third of the ridge. For 30 minutes they advanced unopposed, but when the British neared the halfway point of the ridge heavy fire crashed down upon them. They were pinned down for almost three hours.

The Left Flank commander, Major John Kiszley, recalled having to lie next to his signaller due to the worsening cold. The young man asked the officer what people would think if they were killed and found lying together like that. It made Kiszley wonder how many of his men would succumb to the cold if they stayed where they were. He ordered one of his platoons to collect rocket launchers and machine guns and move up on the left flank. They unleashed a heavy barrage, and Kiszley led his other two platoons in an attack. They reached the top of the ridge only to find it was a false crest because another peak lay beyond it. With artillery support they advanced 800 yards.

On the Argentine side, Sub-Lieutenant Carlos Vasquez’s platoon was facing the British at the center of the ridge. He ran to help a wounded soldier, leaving his rifle behind. As he administered aid, a British submachine gun started firing outside the foxhole. Drawing his pistol and a grenade, Vasquez ran back to his position. Nearby British soldiers fired at him, and he fired back, but no one was hit. A star shell went off overhead, so he pretended to be hit and fell down. The British stepped over him and moved on. After they passed, he ran to the command post. British soldiers seemed to be everywhere, so he ducked into his hole and called for mortars on his own position, hoping to hurt the enemy more than his own troops. The fire pushed the British back. Vasquez was authorized to withdraw but elected to stay and fight.

Another attack came, this time with British machine guns on high ground above the Argentines. Vasquez yelled orders along his line but was forced to stop when this attracted enemy fire. He again called in fire on his own position, but this time the British stayed and started firing again after it lifted. Vasquez saw British troops taking his platoon’s foxholes one by one, attacking from numerous directions and overwhelming the Argentines. This went on until about 7 am when only two foxholes were left. He watched four British soldiers throw a phosphorous grenade into one. A man was wounded and the other shot down as he ran out. The lieutenant called for help on his radio but was told nothing was available. He looked up and saw British soldiers only seven feet away, pointing their weapons. “That was the end for me,” he said.

When he reached the final crest, Kiszley saw the lights of Stanley in the distance. He had a bullet lodged in his compass, which saved his life. A private nearby had taken a bullet in the chest, but it was stopped by one of his magazines. Only six men were with Kiszley at their last objective. Suddenly, a burst of machine-gun fire wounded three of them. Kiszley started giving first aid and told a soldier named Mackenzie to stand guard. The young guardsman told the officer he was out of ammunition and had been since the last hilltop. Kiszley asked the man why he had come. The young man replied, “You asked me to, sir.” The major gave the private his rifle and said, “You brave bastard!” MacKenzie gave a big grin and stood sentry.

Major Simon Price’s Right Flank Company took over at that point. The Right Flank Company used the same methods as Left Flank Company. One platoon would flank to provide fire support while the others used rockets and grenades to destroy fighting positions. Platoon Commander Lieutenant Robert Lawrence led his men forward, firing as they went. An enemy machine gun fired back, and the platoon was pinned down. Lawrence crawled forward with a phosphorous grenade, his men covering him. He got close enough to throw the grenade, but the pin wouldn’t come out. Frustrated, he crawled back, and a corporal held the grenade while he pulled the pin out by brute force. Crawling back to the machine-gun nest, he hid behind a rock with bullets ricocheting off it and threw his grenade. After it exploded he screamed to his men to advance, and every man did. Afterward, they bounded against snipers almost as if they were on a range back in Wales. One man would fire; another would jump up and run a short distance, take cover, and start firing while the next man moved up. As Right Flank Company finished its fight on Tumbledown, Lawrence was hit in the head and evacuated for treatment. He lost the use of his left arm and part of his left leg. His bravery earned him a Military Cross.

It took 11 hours to capture Tumbledown, long enough to upset the British timetable and delay the Gurkha advance against Mount William. The Scots Guards had suffered seven killed and 40 wounded while the Argentines lost around 30 killed, an unknown number of wounded, and 14 captured.

The last major obstacle was Wireless Ridge, a mile north of Tumbledown. The feature is actually two parallel east-west ridges, the southern ridge taller at 300 feet. Three platoons of Argentines held the north ridge, while the southern ridge was occupied by a few support troops along with some mortars. They would face attack by 2 Parachute, supported by four light tanks as well as field artillery and naval gunfire.

A subsidiary attack by the SAS against Stanley Harbor was spotted by a searchlight and fired on. The assault was forced to withdraw with three wounded. Much like the diversion at Tumbledown, this event made many Argentines think they had repulsed a major attack. The actual ground attack had extensive fire support; 6,600 artillery and naval shells were fired. The four tanks used cannons and machine guns until they ran out of ammunition. The mortars of 3 Parachute were attached to 2 Parachute’s mortars to increase its firepower to 16 tubes. A machine-gun platoon supporting the attack fired more than 40,000 rounds. Three of its machine guns were almost burned out by the volume of fire.The bombardment began at 12:15 am, as Companies A and B left their start lines. A half hour later Company D set off from a line farther west. As they advanced, Argentine mortar fire fell, causing an unfortunate para to take cover in what turned out to be a latrine pit. Still, the British pushed forward and started clearing trenches as Argentine 155mm rounds burst in the air overhead. Several soldiers fell into icy ponds that dotted the area and had to be rescued. Meanwhile, the tankers used their night vision equipment to pinpoint enemy positions.

In the hazy light of the star shells, Argentine soldiers were seen fleeing the ridges. A few were hit and fell, but most ran toward Stanley. Quickly the tanks and heavy weapons of the infantry set up on the northern ridgeline and fired over the heads of the advancing paras as they took the southern feature. Soon, the entire terrain feature was in British hands, although the Argentines responded with considerable artillery and small arms fire. More strange occurrences pointed to the vagaries of luck under fire. One British officer was hit by a bullet that sailed between two grenades on his belt and lodged in a rifle magazine. A private heard Argentines shouting as they prepared a counterattack. He heard one yell, “Grenado!” Deciding that was a good idea, he threw one of his own toward the voices in the dark, which were silent afterward.

The counterattacks the Argentines made during the Wireless Ridge fighting were the most energetic of the war. An ad-hoc force of 70 armored car crewmen was beaten back by the parachute troops, resulting in six enemy soldiers killed. A company of Argentine infantry also made an attempt. Their commander, Major Guillermo Berazay, watched the British attack unfold. He was ordered to a start point where some armored car crews would guide him in. When they arrived, no crewmen were there. He reported this and was told to move up the hill. Berazay went forward to place his machine guns, but British troops opened fire. He ordered his infantry up. They advanced into machine-gun and rocket fire, which stopped them cold. Many Argentine troops panicked and fled. The 20 men remaining got up and advanced again, making it to a hilltop. After they were fired on by machine guns, grenades began falling. One Argentine was wounded by a fragmentation grenade only to have a phosphorous grenade set his clothes on fire. The counterattack was soon over, a brave effort but insufficient to turn the tide. Wireless Ridge was lost, along with 14 British casualties (11 wounded and three dead), 100 Argentines killed, and dozens captured.

With the capture of Wireless Ridge, the Battle of Stanley was effectively over. The Gurkhas moved on Mount William but found it abandoned; Sapper Hill was taken without a shot fired. Retreating Argentines were struck with artillery as they fled to Stanley. A Spanish-speaking British captain went on the radio offering a cease-fire to discuss surrender. Within a few hours, it was over. Argentine soldiers lay down their arms and awaited repatriation. Jubilant British troops and Falkland civilians broke out bottles and celebrated the victory.

The war had been a close-run thing. The British suffered from logistical shortcomings at the end of a long supply line. The Argentine Army was a good force compared to many other armies. It simply was not up to fighting the British military, a professional force with better training and discipline. The two forces were similarly equipped, with the Argentines holding advantages in a few key areas. However, superior British morale held and eventually broke their opponents’ will to fight.

For the Argentines, the war was a shameful defeat. Much of the military leadership was removed. Officers over the rank of major were lucky not to be court-martialed. The nation’s leaders had miscalculated and paid a dreadful price. Within days, President Leopoldo Gattieri was removed from office. The victory bolstered national pride in the United Kingdom. The British Lion could still bite.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments