By Robert L. Durham

The French cavalry thundered ahead, straight for the British open square. The red-coated infantry made ready for them, the front-rank knelt with muskets planted in the ground and their fixed bayonets pointed outward. The rear-ranks fired by platoon, as fast as they could reload. Horses screamed, spilling their riders in heaps on the rain-soaked ground. Horsemen that were shot from their horses cried out in their pain, desperately clinging to life, despite their injuries.

Unable to close with the British infantry, the French horsemen wheeled about, firing their pistols in a valiant attempt to break the British line. Having suffered a bloody repulse, the French cavalry reformed in the rear. While the cavalry regrouped, the artillery crews manning the cannon mounted in the Redoute d’Eu on the French right flank shelled the British line. The English soldiers stood firm, and as casualties mounted, men in the rear rank stepped forward to replace those who had fallen in the front line.

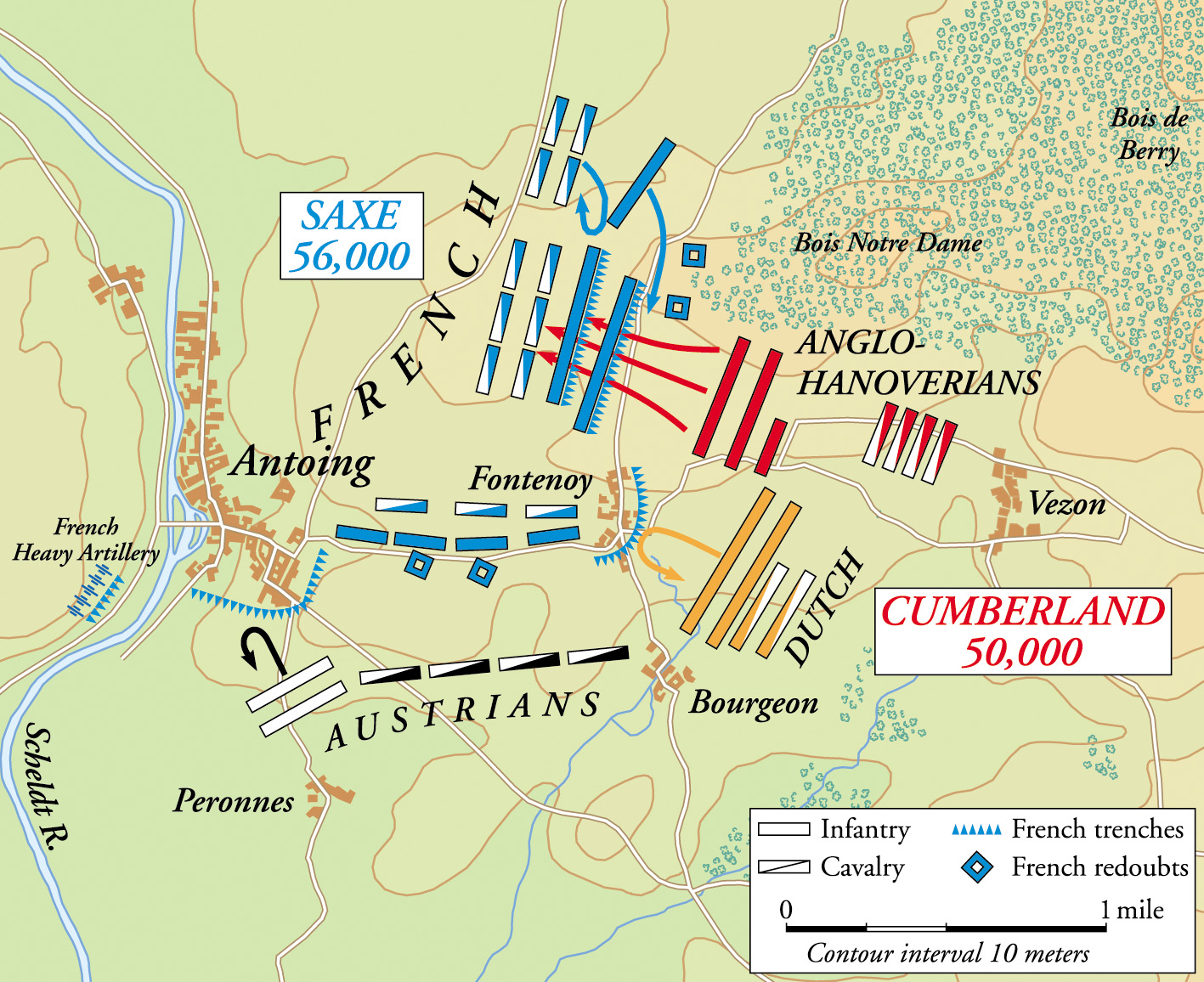

At the start of the Battle of Fontenoy on May 11, 1745, a French army led by Marshal Maurice de Saxe, the Comte de Saxe, suffered an initial repulse at the hands of Prince William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland’s British-Dutch-Austrian army. After that, Saxe decided to remain on the defensive, and Cumberland took the initiative. It was anyone’s guess whether he would have better luck on the attack than had his opponent.

The War of the Austrian Succession began in 1740 upon the death of Emperor Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, and the last male heir to the throne of Habsburg. The Habsburgs were the traditional rulers of the Holy Roman Empire. The seeds of the war were sown in 1713, when the Treaty of Utrecht brought an end to the War of the Spanish Succession. The Pragmatic Sanction, one of the many edicts in the treaty, stated the imperial throne of the Holy Roman Empire, in Vienna, should pass directly to the eldest son or, in the absence of a son, to Charles’ eldest daughter. When he died in 1740, Maria Theresa, his oldest daughter, became heir to the Habsburg Monarchy and the Holy Roman Empire.

Despite the edict, Prince-elector Charles Albert of Bavaria challenged her right to inherit. Charles had the support of France, Prussia, and Saxony. The “Pragmatic Allies” backed Maria Theresa. These included Austria, Britain, Hanover, and the Dutch Republic. As the conflict widened, Spain, Sardinia, Saxony, Sweden, and Russia were drawn in. The pretext for the war was Maria Theresa’s right to inherit from her father, but, in reality, France, Prussia, and Bavaria entered the war because they saw an opportunity to challenge Habsburg power. The two sides would fight battles and sieges in three theaters, which were Central Europe, Austrian Netherlands, and Italy, as well as on the High Seas.

The Pragmatic Army, which included Austrian, British, and Hanoverian forces, defeated the French on June 27, 1743, at Dettingen, in the Electorate of Mainz within the Holy Roman Empire. King George II of Britain led the Pragmatic Army, which marked the last time a British monarch participated in a battle.

The following year Austria and Central Germany became the principal theater of war. Saxe, who was newly promoted to marshal, was the illegitimate son of King Augustus II the Strong of Poland-Lithuania and the Elector of Saxony, and he defended Flanders with 30,000 men against an Allied army twice that size.

Forty-nine-year-old Saxe had compiled an impressive military record. He had served in various armies since his early teens, when he served under the Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Malplaquet fought in 1709 during the War of the Spanish Succession. Afterwards, he served under Prince Eugene of Savoy against Ottoman forces holding Belgrade in 1717 during the Austro-Turkish War.

At the time of the Battle of Fontenoy—a town situated five miles south of Tournai in the Austrian Netherlands—Saxe was seriously ill with dropsy and therefore had to travel by carriage. The marshal, because he was so unwell that morning, could not bear the weight of the steel cuirass he usually wore in battle; instead, he wore a quilted taffeta version. He sucked a musket ball to mollify the thirst caused by his illness.

Field Marshal George Wade, the Allied commander, prepared a plan of campaign that included capturing the important French fortress of Lille. If the Allies could capture Lille, they would substantially compromise the French position in Flanders. In addition, possession of Lille would give the Allies a strong base for a drive on Paris. But Saxe harried Wade incessantly, keeping him off balance. At one point, a French raiding party overran the Allied headquarters. Wade was under such heavy pressure that he relinquished the initiative and withdrew into winter quarters at Antwerp.

Prince William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, assumed command of the Allied army. The 24 year-old duke, who was King George II’s second son, had served with honor at Dettingen, and his peers thought well of him. Britain’s allies confirmed him as Captain-General of His Majesty’s Forces serving in Europe and commander-in-chief of the Pragmatic Army.

From his headquarters in Lille, Saxe began planning for the 1745 campaign, which he intended to begin earlier than usual. This meant the Pragmatic Army would have to respond to French movements rather than execute its own strategy. Cumberland decided to advance to Mons, where the latest information placed Saxe’s army. Mons was one of a string of fortresses that the Allies had established as a buffer between France and the Austrian Netherlands. The duke did not expect Mons to hold out long against the French. What is more, Cumberland did not want to hand the French an easy victory by remaining inactive, so he marched to Mons.

Unknown to Cumberland, Saxe actually intended to strike the fortress of Tournai, which was situated 30 miles northwest of Mons. The French commander detached 22,000 troops from his main army to besiege Tournai, which was held by 9,000 Dutch troops.

Saxe then led his main army, which numbered 50,000 men and 100 guns, on a march to occupy Fontenoy and Antoing, which were five miles southeast of Tournai. In so doing, he blocked the Pragmatic Army’s route to Tournai.

Cumberland was not overly concerned with the possible loss of Tournai, although his Dutch allies were deeply concerned over the matter, because if Tournai fell to the French, Saxe would have an open path into the heart of the Netherlands.

Saxe put his troops to work fortifying the towns of Fontenoy and Antoing. The attackers would have to fight their way through a rock-filled ditch to engage a first line of entrenched musketeers. Behind the trench was another line of musketeers, stationed atop a rampart behind a high wall. Three redoubts strengthened the fortified line between the villages.

The French marshal also established two more redoubts, known as the Redoute de Chambonas and Redoute d’Eu, east of Fontenoy on the edge of the Bois de Barri. The Bois de Barri was an expansive, maintained wood that had no undergrowth. The two redoubts were positioned such that the troops manning them would be able to attack Allied troops if they tried to pass between the town of Fontenoy and the Bois de Barri. However, the French marshal purposely did not fortify the area between Fontenoy and the Bois de Barri because he believed the marshy ravine that ran through the sector made it impassable. But he did deploy the Gardes Francaises brigade in that location as a precaution. In addition, he stationed the two battalions of the Arquebusiers de Grassin Brigade in the woods to fire into the flank of any force trying to assault the Redoute d’Eu, which was the westernmost of the two redoubts.

The Pragmatic Army, which had 50,000 troops and 93 guns, arrived in front of Fontenoy on the evening of May 10, 1745, having marched all day on muddy roads. Cumberland was in the saddle before dawn the following morning to reconnoiter the French positions. A thick mist hung low over the fields, which made it difficult for him to ascertain with great accuracy the strength of the enemy positions. Nevertheless, he decided that the Redoute d’Eu was a primary objective and had to be taken for his attack to succeed. With this in mind, Cumberland sent orders to Brig. Gen. Richard Ingoldsby instructing him to clear any French troops from the Bois de Barri and capture the Redoute d’Eu. Cumberland intended Ingoldsby’s attack would be the first British assault of the morning.

Ingoldsby had a brigade of 2,000 men in five regiments. One of the five regiments was Colonel Robert Munro’s 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot, also known as the Black Watch. Cumberland instructed Ingoldsby to march directly against Redoubt d’Eu and seize its guns. They were to turn the guns on the French, but if that was not possible, then they were to spike them. A detail of British artillerymen accompanied the attack for this purpose.

Ingoldsby began his advance at 6:00 a.m. The Grassins in the Bois de Barri raked Ingoldsby’s right flank with fire as it advanced. Munro suggested to Ingoldsby that he send his light troops to clear the woods, but Ingoldsby ignored his advice. Instead of advancing immediately, Ingoldsby requested that artillery be brought forward to support his attack.

In so doing, Ingoldsby wasted considerable time waiting for artillerymen to bring forward three 6-pounders. At the time, civilian contractors drove the cannon to the battlefield, dropped them off where ordered, and then took their horses to the rear to wait out the battle. When Cumberland sent the guns to Ingoldsby, the gunners had to painstakingly manhandle them into place.

Cumberland, who became deeply frustrated with Ingoldsby for the time-consuming delay, rode forward to issue orders to the artillerymen. He instructed them to fire canister into the Bois de Barri to drive off any French troops on the edge of the wood. Believing that Ingoldsby would advance since he now had artillery support, the duke rode off to attend to matters on other parts of the battlefield.

With Munro’s Royal Highlanders in front, Ingoldsby’s troops advanced along a sunken road, but the advance soon ground to a halt when the Grassins poured a heavy fire into the troops at the front of Ingoldsby’s column. The Grassins were skilled sharpshooters. Men in the back of the formation passed loaded muskets to those in the front. With the front of his column taking considerable casualties, Ingoldsby again halted his advance. When he learned of the delay, Cumberland returned to Ingoldsby’s location to assess the situation himself. He admonished Ingoldsby to no avail. Ingoldsby, who greatly overestimated the number of French troops in the Bois de Barri, spent the remainder of the battle sheltering his troops in the sunken lane.

Cumberland then ordered Lt. Gen. James Campbell to take his 15 squadrons of cavalry forward in an attempt to prompt Ingoldsby into advancing. Unsuccessful in this endeavor, Campbell led his men forward past the Bois de Barri. The guns of Redoute d’Eu shelled the British and Hanoverian horsemen. A cannon ball struck Campbell in the thigh, nearly shearing off his leg and mortally wounding the general. At that point, command of the leading horsemen devolved to Maj. Gen. John Lindsey, the Earl of Crawford. Crawford withdrew his cavaliers out of the French cannon fire, and they reformed behind the British infantry.

Cumberland did not interfere with Crawford’s decision; staying where they were would have done little good, for the cavalry would only have interfered with the British infantry, which was deploying into line of battle. What is more, the cavalry would have been exposed to the enemy artillery fire. The constrained nature of the terrain on the Allied right flank allowed no room for cavalry and infantry to function in concert with each other.

At that point in time, King Louis XV was crossing the Scheldt River at Calonne with the Dauphin Louis and Marc-Rene de Voyer, the Comte d’Argenson and the French minister of war, in order to take up a position on the center-right of the French army to observe its progress. Two squadrons of Gardes de Cheval stood nearby as close escort to the king. Although deferential to the king, Saxe did not appreciate the distraction the monarch’s presence on the battlefield caused. The marshal instructed his aides to make sure that an easily accessible route back across the Scheldt remain open, with the guard of Royal Grenadiers in place for protection in case circumstances required that the king and his royal party needed to leave the battlefield in a hurry.

Saxe worried Cumberland might turn his left flank. Because of this, he issued orders to his artillery crews that once the morning mist had cleared, they were to shell the Pragmatic Army. When the French gunners went into action, the Allied gunners responded. The consequence of the bombardment and counter-bombardment was largely ineffective.

When the artillery fire had died down, Lt. Gen. John Ligonier advanced his infantry lines. Saxe personally directed the artillery fire. In addition to artillery firing from fixed guns, smaller French guns went into action in front of the infantry.

The Anglo-Hanoverian troops stood up to the artillery fire quite admirably. They closed their ranks whenever the French firing opened a gap in their lines. Once they had completed their move, a second line advanced. Cumberland ordered seven light guns muscled forward to drive away the French gunners.

Louis, the Duc de Gramont, the commander of the Gardes Francaises, was mounted on a white horse. He made an easily identifiable target for British gunners, who fired round shot at his position. The cannon ball shattered his thigh, inflicting a mortal wound. As he was carried to the rear, Saxe ordered Louis Antoine de Gontaut, the Duc de Biron, to replace him. Saxe also withdrew the Gardes Francaises and the Gardes Suisses to a safer position so they would not suffer needless casualties from Allied artillery fire.

At that point, Cumberland went yet again to speak to Ingoldsby, but by that time he had abandoned the idea of having his subordinate silence the guns in the Redoute d’Eu. It may have become apparent to Cumberland that the strength of the infantry reserves posted on the French left flank meant that Ingoldsby did not have enough strength to capture the redoubt. Thus, Cumberland was forced to abandon a key part of his battle plan.

Cumberland dispatched a messenger with orders to Prince Karl August Friedrich of Waldeck-Pyrmont instructing him to commit the Dutch infantry against the entrenched French forces between Antoing and Fontenoy. Four cannon shots signaled the start of the attack. At the signal, two Dutch cavalry columns moved forward and took up positions to support the attack.

Next, long lines of blue-clad Dutch soldiers advanced with bayonets fixed towards the French right wing. French infantry from the safety of redoubts and trenches fired on the Dutch infantry, and French shells blew gaping holes in the Dutch formations.

The eight battalions of the Waldeck Infantry Regiment drifted towards the right during the advance. This opened a large gap in the Dutch line. As the advance continued, the Dutch battalions veered towards the village of Fontenoy. Waldeck brought forward three dragoon squadrons to restore the proper direction of attack of the Dutch line. Sending their horses to the rear with the horse holders, they went in with the infantry.

Despite the mist that partly concealed their advance, the Dutch infantry stood no chance against the French artillery. French musket fire felled the majority of the officers and men in the front ranks. The Dutch foot soldiers leaned their bodies forward as they advanced into the whirlwind of enemy musket and artillery fire. Although they made a valiant effort, the Dutch could not make any appreciable headway. They eventually fell back to reform their torn and tattered ranks.

The Prince of Waldeck-Pyrmont brought forward the second Dutch column, but it was hit by the same 16 guns arrayed in the three redoubts that the first column had experienced. The attack of the second column also broke under the French fire. It was obvious they had no chance to reach and breach the French position. One of the Dutch cavalry squadrons retreated entirely from the field, galloping completely out of the fight. The Dutch infantry and cavalry squadrons were still in range of the French artillery, which fired on them with no retaliation. The feeble Dutch attack had lasted no more than an hour.

At 11:00 a.m. Cumberland sent the Hanoverian Borschlanger Regiment into the Bois de Barri with orders to capture Redoute d’Eu at any cost. This met with the same result Ingoldsby had experienced. Simply put, artillery positioned in the Redoute d’Eu shattered the attack.

The duke then transferred two regiments, one of which was the Black Watch, from Ingoldsby’s command to the left to reinforce a renewed Dutch attack. Field Marshal Christian Moritz Konigsegg-Rothenfels, commander of the Austrian troops in the Allied army, requested that a British four-gun battery of howitzers be brought forward to support the attack. The Borschlanger Regiment marched north to support the assault. Cumberland entrusted Colonel Scipio Duroure with leading the troops that would participate in the assault. Duroure led the assembled troops forward to attack the French, who were entrenched in the town.

At that critical moment, a French musket ball wounded Ingoldsby. The command of his diminished brigade fell to Hanoverian Maj. Gen. Ludwig von Zastrow, whose men carried Ingoldsby to safety.

Munro’s highlanders advanced along a sunken road and attacked the French, catching them by surprise. “They rushed upon us with more violence than ever sea did when driven by a tempest,” recalled a French eyewitness. Munro instructed the men of the Black Watch to lie prone upon receiving the French volleys, and then rise to fire their own volleys. Munro, though, did not go to ground. He remained standing because of his stoutness. He feared his men would have to help him to his feet if he were to lie down, which would be an undignified sight.

The Scotsmen of the Black Watch carried their broadswords into battle, and they used them in hand-to-hand fighting with the French Dauphin Regiment. It was an uneven fight, for the Scotsmen had a considerable advantage with their broadswords. They drove back the French infantry with which they were engaged and then overran a French battery. The French gunners who were unable to escape were cut down next to their guns.

Saxe then ordered the du Roi Regiment forward to reinforce the troops defending Fontenoy. The arrival of the reinforcements enabled the defenders to rally and repulse Duroure’s assault. After that repulse, Waldeck-Pyrmont attacked the village with his Dutch infantry, but the French repulsed that assault, as well.

Despite their bravery, Munro’s highlanders had to withdraw because Waldeck-Pyrmont’s second attack met a hail of round shot and canister. Duroure’s men suffered severe casualties in their attack on the village of Fontenoy. Of Duroure’s officers, only Captain Charles Rainsford of the 12th Foot remained standing. He extricated the soldiers from the cottages and gardens of Fontenoy to retreat as best as they could. Despite Cumberland’s best efforts, Saxe’s right flank and center held their original positions.

Next came the turn of the vaunted British infantry to try to break the French left center. They formed themselves into two lines totaling 16,000 men. Cumberland accompanied them on horseback with his staff as they began their advance.

Taking posts of honor on the right in the first line were the 1st Foot Guards (Grenadier Guards), 3rd Foot Guards (Scots Guards), and the 2nd Foot Guards (Coldstream Guards). Next in seniority came the Royal Brigade and Onslow’s Brigade. Deploying behind them in the second line were Howard’s Brigade, Sowle’s Brigade, and the remainder of the Hanoverian Brigade.

Cumberland intended to thrust his Anglo-Hanoverian infantry through the left center of the French line, and then wheel left to roll up their position. The attack occurred simultaneously with Duroure’s second attack on Fontenoy in order to put the maximum pressure possible on the French army.

The British formation moved 800 yards up the wet slope, advancing through the marshy ravine that Saxe had believed to be impassable. They marched with their drums beating and colors flying. French artillery shelled them from both sides. The gaps in the ranks caused by the artillery were bravely closed with the soldiers dressing to the right.

Suddenly, the French Guard and Swiss Guard brigades and three regiments rose up from a sunken road 70 yards in front of the Allied troops. They fired a heavy volley into the surprised British infantry, but it was largely ineffective because the French soldiers aimed too high. Those men in the front of the Anglo-Hanoverians that fell were swiftly replaced by the rear-rank men. The British in the front returned the volley, firing by platoon rather than by rank. Men in the rear rank loaded muskets and passed them forward to the front rank. The rolling fire of the British impressed the French.

After firing, the British infantry advanced through the smoke from their muskets, getting steadily closer to the French with each volley until they were at point-blank range. The British volley fire mauled the French and Swiss Guard brigades. Both formations broke under the weight of the attack. The ground where they had stood was littered with 400 dead and dying Frenchmen.

“The French Foot Guards ran away at the first fire, as [they had] at Dettingen,” wrote Major Richard Davenport of the British Horse Guards, referring to the battle two years earlier when King George II had decisively defeated a French army in Bavaria.

Saxe then committed his last infantry reserves in a desperate bid bring Cumberland’s seemingly unstoppable advance to a halt. “They advanced as if performing a part of their exercise, the sergeant majors leveling the soldiers’ muskets to make their discharge surer,” wrote a French participant.

The Irish Brigade, serving with the French, was commanded by Charles O’Brien, the Comte de Thomond, moved forward to strengthen the French line. But since they had no support, they were compelled to fall back. Much of the French infantry were routed into a panicked flight. “There was one dreadful hour in which we expected nothing less than a renewal of the affair at Dettingen,” wrote the D’Argenson.

The fire from the Redoute d’Eu and the Grassin light infantry in the Bois de Barri caused some confusion in the ranks of the British battalions. However, order was quickly restored, and they fixed bayonets and moved forward, urged on by Cumberland. The effect of the French artillery fire gradually lessened as the ammunition supplies were reduced. With this diminished impediment, the vital left-center of Saxe’s position was carried. The staunch British infantry seemed to have pulled victory from what previously seemed to be near-certain defeat.

Saxe’s best infantry regiments had collapsed. It seemed that the French were on the verge of a disaster. The marshal hurried from the field to the king, who remained calm. Noailles urged the king to withdraw, with the Dauphin, to safety across the Scheldt. “I am going to stay where I am,” said Louis. Saxe offered some reassurance by pointing out that he had reserves stationed nearby.

The compact column of Allied infantry moved relentlessly forward, inclining slightly to the left away from the harassing fire from the Grassins in the Bois de Barri. The British soldiers calmly continued firing volleys as they advanced. The Aubeterre Regiment, which stepped forward to try to stop their advance, was shattered by the volley fire.

Saxe then ordered the Roi Regiment against the flank of the British column, but they also were repulsed with heavy losses by the 2nd Foot Guards. The Hainault, Royal, and de Vaisseaux Regiments shifted from behind Fontenoy to try to close the gap and restore the French line. The rolling volleys of the British infantry, though, thwarted their effort, inflicting heavy losses on the French infantry.

At that crucial moment, Saxe ordered a cavalry charge. The British infantry, upon hearing the thunder of hooves, refused their flanks and brought forward the 3-pounder cannon that had been dragged forward by the grenadier companies.

The French cavalry attack lacked the power that Saxe had expected. This was because Louis-Charles Le Tellier, the Comte of Estrees, who commanded the Brigade de Royal-Cravates, did not bring forward his entire cavalry force. He ordered just four regiments, numbering about 2,500 men, to make the assault. The men and horses advanced at a measured pace toward the British infantry. The cavaliers kept from charging in order that they would not tire too quickly. “It was like charging two flaming fortresses rather than a column of infantry,” recalled one French officer.

The British cannoneers fired off their last load of double-shotted canister, which left knots of struggling, shrieking horses before them, then ran for shelter into the infantry column. The front-rank men knelt on one knee, the butts of their muskets planted in the ground with bayonets pointed outward. The second and third ranks were prepared to deliver their death-dealing volleys. When the French cavalry was 50 yards away, the British line opened fire. The French cavaliers, unable to close with the British and use their swords, wheeled in front of them, firing carbines and pistols. Two more French cavalry regiments came to their aid, but to no avail. Those cavaliers who survived retreated.

A few of the cavaliers managed to force their horses into the ranks of the 2nd Foot Guards, but all were swiftly shot or bayoneted. The Royal Roussillon Regiment tried once again. The ground was littered with dead and wounded horses and men, so they came on at a walking pace, only to be driven back as all those before them. Although driven off, the cavalry had achieved its objective, which was to stop the British advance.

As the British lines advanced again, they found there was not enough space between the town of Fontenoy and the Bois de Barri to keep their formation. All that stood between them and victory seemed to be two lines of French cavalry. As the British pushed on, the space of the gap and the threat from the remaining French cannon caused the men to instinctively move away from the flanks, causing the lines to contract. The battalions deepened their formations. Eventually, they formed three sides of a giant square, leaving the rear open. Maj. Gen. Ludwig von Zastrow’s Hanoverians served as a ready reserve inside the square. The further they advanced, though, the more the Anglo-Hanoverians exposed themselves to being taken in the flank.

Saxe decided at 12:30 p.m. the time was right to counterattack. He ordered the three infantry regiments that had rallied to attack the west side of the Allied square while two others assailed the north side of the square. The French regiments outnumbered the British regiments, which had been under a concentrated cannonade for hours.

However, Saxe’s plan was nearly undone when Joseph de Randon, the Comte d’Apcher, launched an attack without orders. D’Apcher sent two regiments of cavalry against the west side and northwest corner of the Allied square. Some of the cavalry recoiled at volleys from the British line, but four squadrons of the Noailles cavalry cut their way through the ranks of the 3rd Foot Guards before running headlong into the Hanoverian reserves. Just 14 cavaliers from the lead squadron escaped with their lives.

Estree ordered a brigade of cavalry forward to cover the retreat of d’Apcher, and the confusion prevented the advance of the Irishmen. Cumberland, seeing the hesitation in the French ranks, directed the Earl of Albemarle to order the 2nd Guards to advance towards the nearest enemy and give a close-range volley. Cumberland then changed the angle of the British attack to veer away from the Bois de Barri toward the northern end of Fontenoy.

King Louis ordered Louis-Philippe d’Orleans, the Comte de Montesson, to advance the Maison du Roi and Carabineers of the French cavalry to form a support for the unnerved cavaliers. But they attacked without orders. Charging toward the British line, they saw a repeat of the other French cavalry charges when the British infantry opened on them, emptying saddles and felling horses.

The French army was barely hanging on when Saxe received a report that the artillery in Fontenoy was out of round-shot and canister. They were firing blank cartridges. Saxe, who was convinced that the British superiority was exhausted, decided to assemble as much fresh artillery as possible against the British-Hanoverians and attack with fresh troops.

The Irishmen had seen little action, and others were comparatively undamaged. They had 13 battalions to pit against the exhausted British. Moreover, two brigades of reinforcements were already on the way from Sainte-Trinite. They would place another seven battalions at his disposal. Lowendahl would also bring two fresh cavalry brigades, one of them the cuirassiers. Saxe’s left flank, anchored on Fontenoy, stood firm.

Even so, a sense of gloom hung over the French senior commanders at 1:00 p.m. Saxe was the only one that remained optimistic about a French victory. Noailles advised King Louis and the dauphin to retreat across the Scheldt River for safety, but the king refused to consider such a move. He would not betray the trust of Saxe. The local attacks Saxe had ordered had been driven off, but they had succeeded in halting the seemingly relentless advance of the British column.

Saxe rallied the Normandie and Vaisseaux regiments and sent them back into action buttressed by the remaining soldiers of the Gardes Francaises and Gardes Suisses. He ordered the Irish troops, one of his last available reserves, to strike the Allied column. The Irishmen advanced to the sounds of the fife and drum. British musketry tore through their ranks, but they carried their attack forward and clashed in a sharp melee with the British infantry. The British succeeded for a time in checking the Irish attack, but the balance of the melee tipped in favor of the French when the Normandie Regiment charged some of the British cannon, thereby relieving the pressure on their comrades. Together, the Frenchmen and Irishmen drove back the British.

At that point, Cumberland accepted that his army had been fought to a standstill by the French. He therefore focused on disengaging his troops, which was always a difficult task. When the British and Hanoverians began their retreat, Saxe ordered his cavalry forward again. The French horsemen, though, mistakenly attacked the Irishmen on their side, mistaking their red coats for those of the British infantry. The cavalry, to their credit, realized their mistake and charged the British.

British line troops formed squares, but the weight of the French cavalry attack succeeded in breaking the formations. With their squares collapsing, battalions of British infantry fought their way eastward. At that point, the bottleneck between Fontenoy and the Bois de Barri became an impediment for the counterattacking French, as it had been for the attacking British. Saxe tried to funnel as many as 30 infantry battalions through the narrow gap in pursuit of the fleeing British.

The Earl of Crawford brought up his cavalry brigades to cover Cumberland’s retreat. Since there was no way to avoid the French artillery fire, Crawford flung his men into the French infantry ranks, slowing their advance but with a great loss of cavaliers and horses. Saxe, seeing that nothing more could be done, called off any pursuit. The two armies slowly disengaged. The battle drew to a close at 2:00 p.m. The French marshal then rode off to inform his king that the French forces had been victorious.

After meeting with the king, Saxe ordered his cavalry to secure the artillery and munition wagons abandoned by the retreating Allies. He also arranged for the gathering of the dead and wounded of both sides.

French pressure increased on the Dutch garrison at Tournai after the Pragmatic Army’s defeat at Fontenoy. As a result, the Dutch garrison in the strategic fortress retreated into the citadel on May 22. Thus, they surrendered the town to the French. The French besieged the citadel on June 1, and it capitulated 18 days later. The terms of surrender stipulated they would not bear arms against France and her allies on the continent until January 1, 1747.

Just as the Dutch had feared, Saxe then marched into the Austrian Netherlands. He captured Bruges without firing a shot. Over the course of the next few weeks, four more major towns yielded to the French.

By the end of 1745, the French occupied most of the Austrian Netherlands, threatening the British links with Europe. Through his brilliant operations in the Austrian Netherlands, Saxe had cemented his reputation as one of the great captains of the 18th century and restored French supremacy in Western Europe.

But the British Navy’s blockade had a crippling effect on France, and it forced the French to the peace table. In the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748, King Louis XV agreed to withdraw from the Austrian Netherlands and return the Dutch barrier forts. The people of France were both shocked and disappointed with the king’s decision.

As for the central matter of the Austrian succession, all parties agreed to accept the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713. This confirmed Maria Theresa as her father’s heir. But Austria did not come out a clear winner because it lost key territory. The British compelled the Austrian queen to cede the wealthy province of Silesia to Prussia. Maria Theresa was determined to try to take back Silesia. In the final analysis, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle established only a brief peace, for the Seven Years’ War erupted the following decade.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments