By David A. Norris

In the shadow of Cedar Mountain on the southern outskirts of Culpeper, Virginia, Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson deployed the troops at the head of his column of march against a reinforced Union corps on August 9, 1862. Jackson’s left wing anchored in the woods west of the Culpeper Road suddenly came under heavy attack. “Crash succeeded crash; the mighty thump of the shells against the forest trees was not heard for the din of the musketry,” recalled Lieutenant John M. Gould, a regimental adjutant with the 10th Maine Infantry. “Rising higher and more terrible than all was the hurrah of the boys of our own brigade as they pushed back their foe.”

A Confederate battalion on the left flank dissolved before the oncoming wave of shiny Union bayonets and swirling powder smoke. Assailed on both its front and its suddenly unprotected flank, the adjacent Confederate regiment crumbled, exposing the next unit in the Confederate battle line. Caught by surprise, Confederate regiments fell like dominoes one after another, and the Battle of Cedar Mountain was shaping up to be the greatest disaster of Jackson’s impressive career as a Confederate general.

On June 26, 1862, Maj. Gen. John Pope took command of the 50,000 troops of the Union’s newly constituted Army of Virginia, which was tasked with defending Northern Virginia while Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac battled General Robert E. Lee’s Confederates east of Richmond.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Pope graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1842. Appointed a brigadier general of volunteers on June 14, 1861, he succeeded in opening the upper Mississippi River nearly to Memphis, Tennessee, by capturing the Confederate strongpoint of Island Number Ten in early spring 1862.

Puffed by his successful campaigns west of the Appalachian Mountains, Pope arrived in the East and issued proclamations that sounded both harsh and pompous. Pope’s General Order No. 5, issued on July 18, 1862, directed his troops to “subsist upon the country” in Union-occupied territory in Northern Virginia at the expense of disloyal secessionists. In a subsequent general order he vowed to exile all residents who refused to sign an oath of loyalty.

Pope went on to anger his own men nearly as much as he did the Confederate sympathizers. He introduced himself in a message with the phrase, “I come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies,” which hardly endeared him to the eastern troops.

Pope’s army was fashioned from three small Federal armies operating in the Shenandoah Valley and Northern Virginia. In the Union Army of Virginia, Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel commanded the I Corps, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks led the II Corps, and Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell commanded the III Corps. From his position north of Richmond, Pope had orders to monitor the Shenandoah Valley and shield Washington, D.C., from offensive moves by Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

McClellan had attempted to advance up the Virginia Peninsula in spring 1862 as a way to reach Richmond quickly and avoid Confederate defenses in Northern Virginia. His army had advanced close enough to Richmond to hear the capitol’s church bells. When General Joseph E. Johnston, the commander of the Confederate forces defending Richmond, was severely wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, Confederate President Jefferson C. Davis selected General Robert E. Lee as Johnston’s replacement. When Lee assumed command, the tide of battle shifted in favor of the Confederates.

Under its new commander, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia struck McClellan’s army in one attack after another during the Seven Days Battles. Not every attack was successful, but in the face of the aggressive shift in the Confederate strategy, McClellan fell back repeatedly. As he fell back in the face of persistent Confederate attacks, McClellan shifted his base from White House Landing on the Pamunkey River, a tributary of the York River, to Harrison’s Landing on the James River. After the Union victory at Malvern Hill on July 1, which ended the Seven Days Battles, McClellan withdrew his forces to Harrison’s Landing, where they bivouacked under the protective firepower of Union gunboats. Lee retained the bulk of his army in position to defend the Confederate capital until such time as McClellan departed the Virginia Peninsula.

Originally, the Union’s War Department intended Pope to join McClellan’s drive against Richmond. With McClellan defeated, the plans were reversed. It was now McClellan who was to move by land and water to join Pope in Northern Virginia. When combined, the Union armies would have 130,000 troops against 80,000 Confederates.

McClellan lingered along the James long enough that Lee turned his attention northward toward Pope. Lee focused his attention on the need to protect Gordonsville against Pope, who was advancing cautiously towards that strategically important town. Gordonsville, where the Virginia Central and Orange & Alexandria railroads met, was a vital rail junction through which passed food and supplies from Shenandoah Valley to the Army of Northern Virginia.

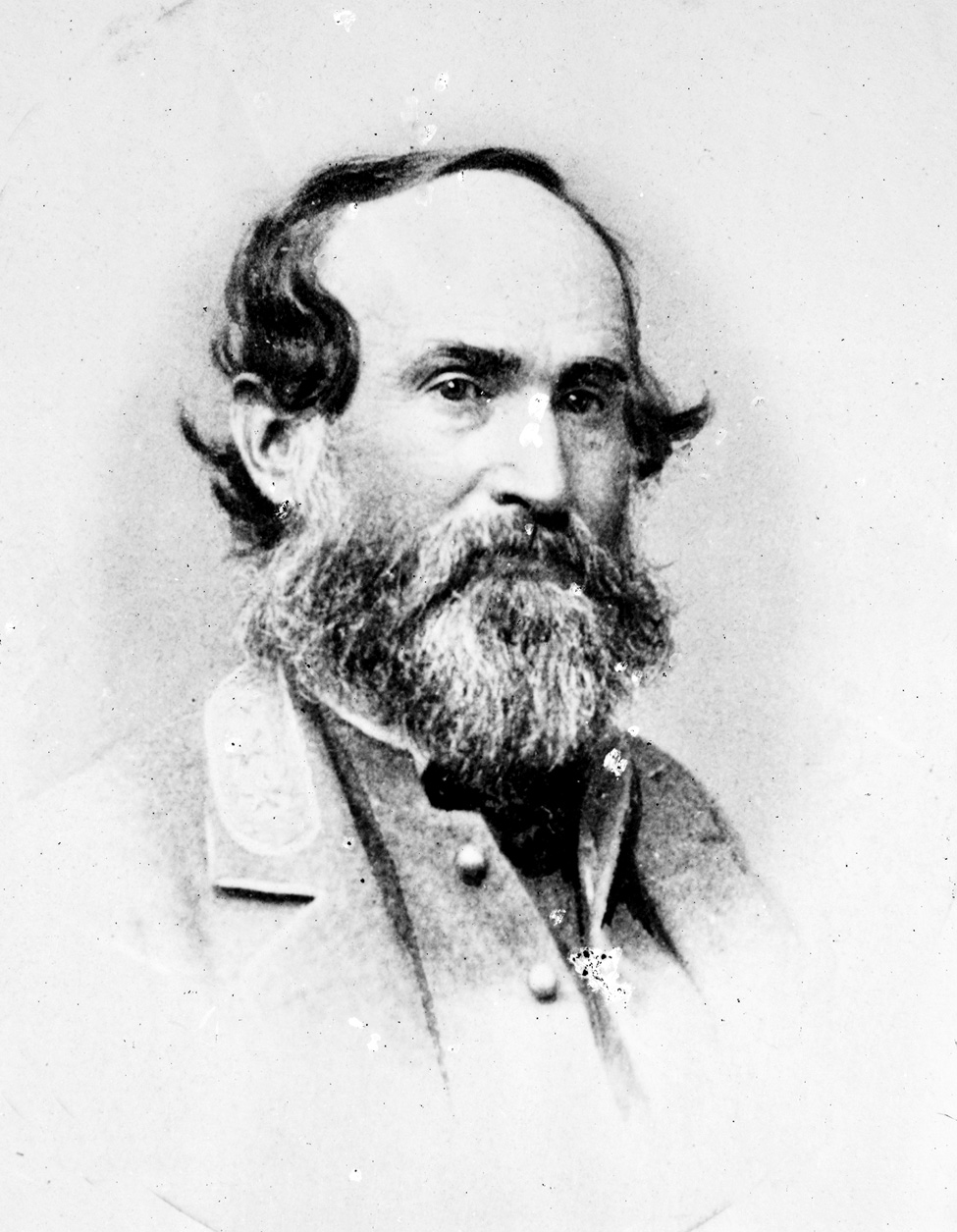

Lee dispatched Jackson with just two divisions to protect Gordonsville, where he was to observe Pope’s movements. Old Jack arrived at his objective on July 19. Jackson’s force initially consisted of just his old division, which was led by Brig. Gen. Charles Winder, and the division of Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. Winder commanded four brigades, and Ewell led three.

Lee heavily reinforced Jackson by ordering Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill’s large division to join him at Gordonsville. Hill set out from Richmond on July 27. The addition of Hill’s 10,000 troops gave Jackson nearly 17,000 men. It also gave him enough troops to engage Pope.

Pope issued orders on August 6 for his 28,000 troops to converge on Culpeper Courthouse, which was 30 miles northeast of Gordonsville on the Orange & Alexandria line. When Jackson learned of Pope’s advance, he set his troops in motion toward Culpeper.

Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, whom President Abraham Lincoln had appointed to serve as general-in-chief of all Union armies, instructed Pope not to seek battle until reinforced by McClellan. Halleck also warned Pope not to allow Lee’s army to get between his army and McClellan’s forces once the latter reached Northern Virginia. To keep a watchful eye along the line of the Rapidan River, Pope dispatched Brig. Gen. George D. Bayard’s cavalry brigade. They passed through Culpeper and set up a picket line along the river.

The cruel August sun blazed across the sky, radiating its heat upon the Union foot soldiers as they trudged toward Culpeper. Men fell from the ranks from exhaustion and sunstroke. “Clouds of dust hung over us, there was not a breath of air, and the road was like a furnace,” recalled Brig. Gen. George H. Gordon. (Gordon commanded one of two brigades in Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ First Division of Banks’ II Corps.)

In the 28th New York, as many as 10 men and two officers died on any given day. As the bluecoats marched by orchards, hunger and thirst drove men to pluck and devour tart, unripe green apples, which knocked more men out of the ranks with intestinal disorders. “If we were not conforming to Pope’s order to live on the country, we were doing the next best thing—we were dying on it,” wrote Gordon.

Pope was in force at Culpeper Court House on August 8, but under pressure from Jackson’s advance, Bayard fell back from the Rapidan toward Culpeper. Pope summoned Banks to join him, as well as Sigel, and sent Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford’s brigade of Williams’ division ahead to meet Bayard. Brig. Gen. James Ricketts’ division, which belonged to McDowell’s III Corps, marched three miles from the courthouse and halted along the Culpeper Road.

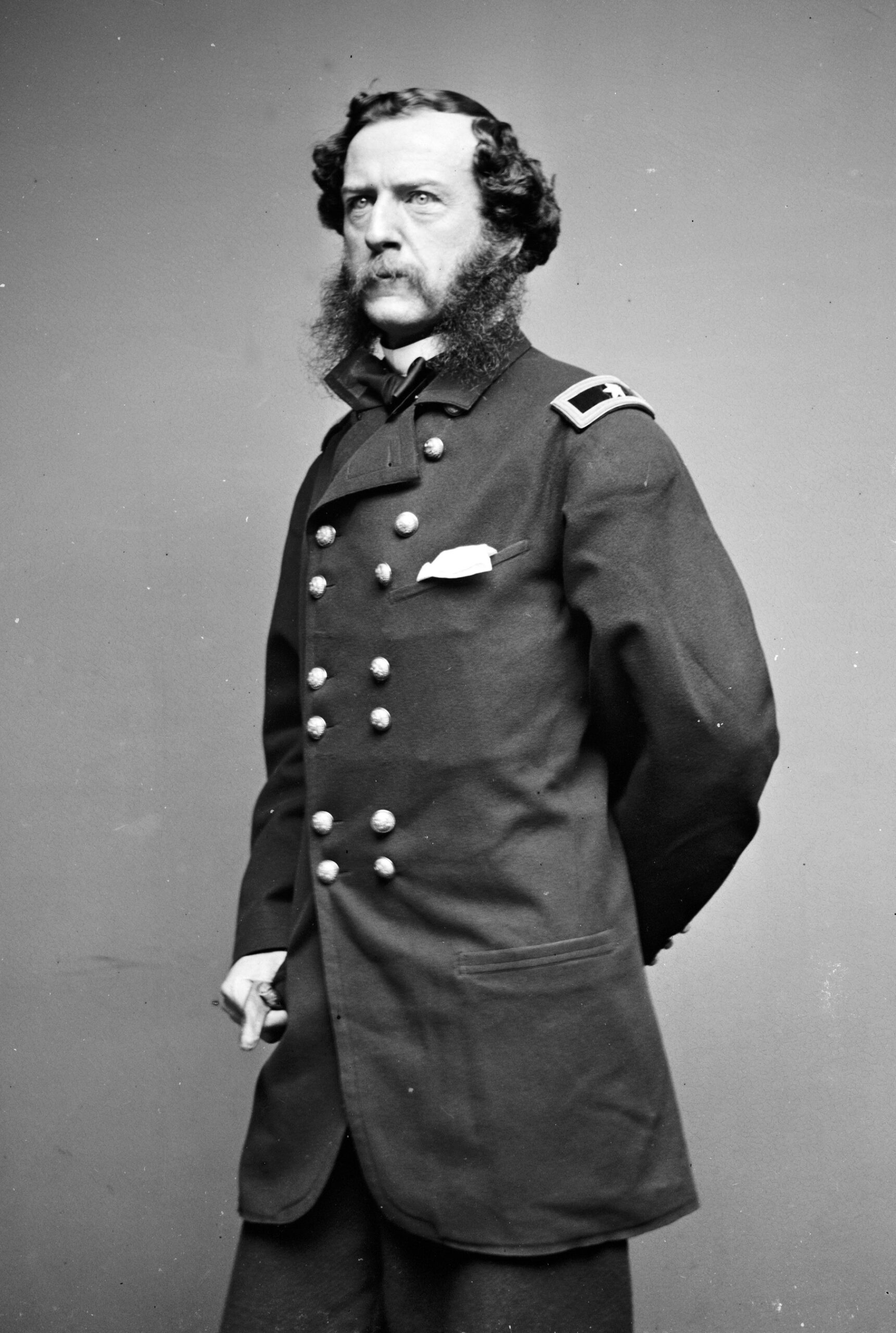

Crawford had been in the war since the beginning. He was an army surgeon stationed at Fort Sumter during the bombardment of April 12, 1861, that triggered the war. Quickly transferring to the infantry, Crawford attained a field command by mid-1862, but had not seen any action since Fort Sumter.

With four infantry regiments, six 3-inch Ordnance Rifles, and four 10-pounder Parrott Rifles, Crawford joined Bayard at 4:00 p.m. Bayard had fallen back several miles and halted between the south and north forks of Cedar Run. Crawford inspected the front and spotted some enemy pickets and cavalry, so he brought up his artillery and posted his own pickets and cavalry to keep an eye on the Confederates.

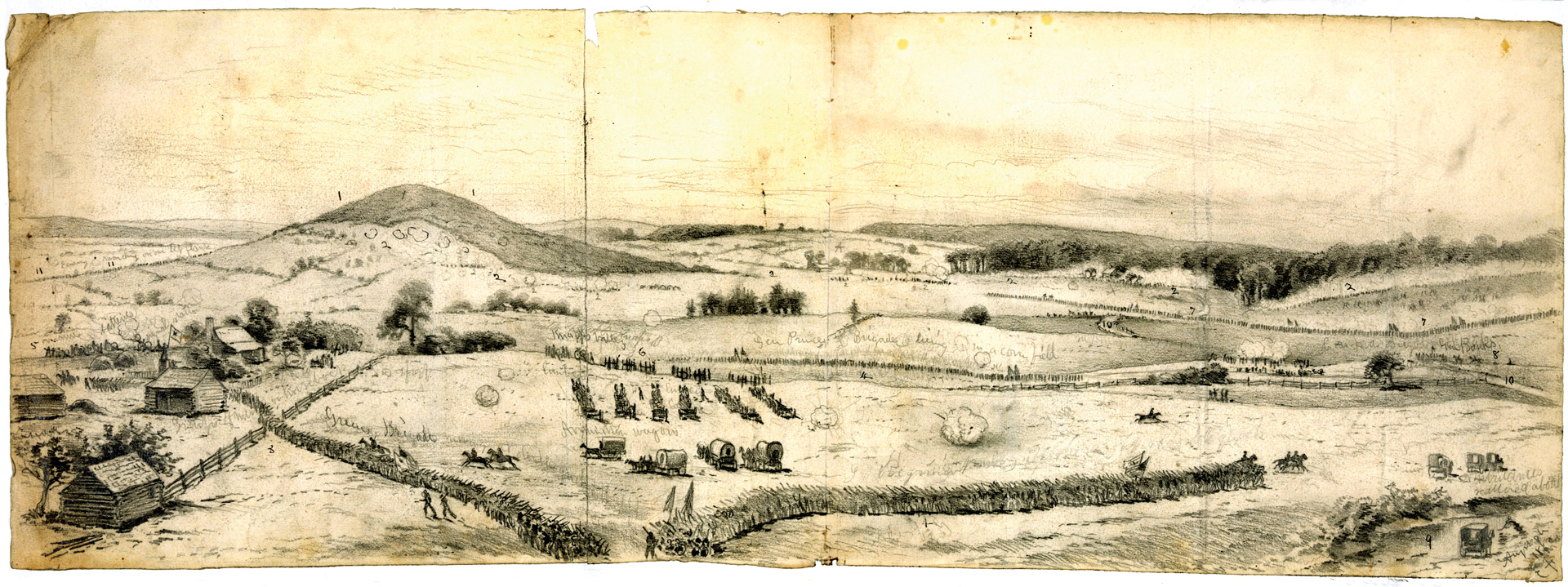

One mile to the southeast of their camp loomed Cedar Mountain. An isolated, rocky ridge more than one mile long, Cedar Mountain rose high above the surrounding undulating terrain. A planter named Daniel Slaughter lived on the land. Early accounts referred to the battle by various names. In addition the Cedar Mountain, it was also called Slaughter’s Mountain and Cedar Run Mountain.

Jackson intended a quick advance to confront Pope, but his secretive nature kept his generals from knowing his plans, which cost him most of a day’s progress. On August 8, Ewell was to march first, followed by Hill. But Jackson changed his mind. To better protect the wagon train, he decided to send Ewell down a different road. But he failed to notify Hill of the change.

The next morning, a column of troops marched past Hill, who waited under the impression that they were Ewell’s men. Hill found out the men belonged to Winder’s command and not to Ewell’s command, but he stayed in place rather than push through the column and scramble Winder’s order of march. In the belief that his orders were being deliberately disobeyed, Jackson confronted Hill. More arguing and delays followed, and Hill claimed Jackson sent orders for him to backtrack to Orange Courthouse. The Culpeper Road was so jammed with troops, horses, wagons, and artillery that Ewell and Winder made only a few miles that day and bivouacked far from Culpeper.

On the morning of August 9, Banks’ remaining 7,000 men were about three miles north of Crawford and Bayard, further back along the Culpeper Road. Pope sent orders at 9:45 a.m. for Banks to join Crawford.

Pope’s orders stoked considerable controversy for years afterward. The orders arrived by one of Pope’s aides, Colonel Louis H. Marshall, who was a Union loyalist nephew of Robert E. Lee. At Banks’ insistence, an officer wrote down the verbal order delivered by Marshall: “General Banks to move to the front immediately, assume command of all forces in the front, deploy his skirmishers if the enemy approaches, and attack him immediately as he approaches, and be reinforced from here.” Banks rode to check with Pope in person to confirm his orders, and Pope told him that a staff officer, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Stone Roberts, who was familiar with the area, “would designate the ground you are to hold.”

With Roberts, Banks rode over the countryside that was destined to become a battlefield later that day. Roberts told him that Crawford’s position along Cedar Run was the best place to place his troops. But Roberts went beyond just designating the ground for Banks to deploy; he told the II Corps commander that “there must be no backing out this day.” Banks found the remark insulting.

That same morning, Jackson left his wagon train under guard at the Rapidan and pushed his three divisions across the river. Ewell’s division led, followed by Winder and Hill.

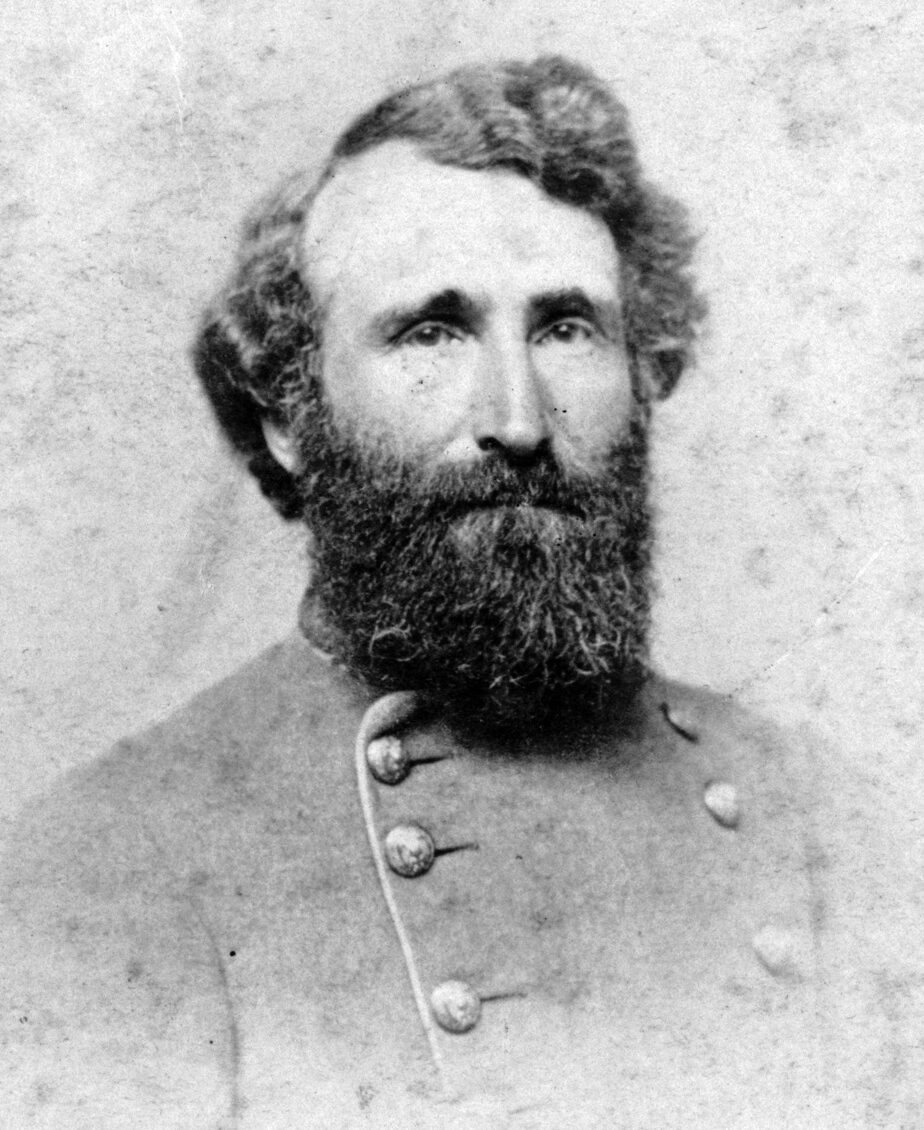

Ahead of the Confederate column, troopers belonging to Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson’s brigade of Virginia cavalry spotted the Union horsemen. Brig. Gen. Jubal Early’s foot soldiers from Ewell’s division moved to the front. They halted along Culpeper Road where a gate opened onto a dirt road that led to the Crittenden farm. Confederate guns unlimbered and fired, spurring a substantial return fire from the Union batteries.

One mile west of Cedar Mountain, Ewell and Early halted at a farm owned by a family named Petty. Jackson arrived to find Ewell playing with the family’s children on the porch. Scant information came back from cavalry patrols, for Robertson was not nearly as effective a cavalry commander as Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. So Old Jack had only a vague idea of the enemy’s positions, and he apparently believed all of the enemy troops were south of the Culpeper Road.

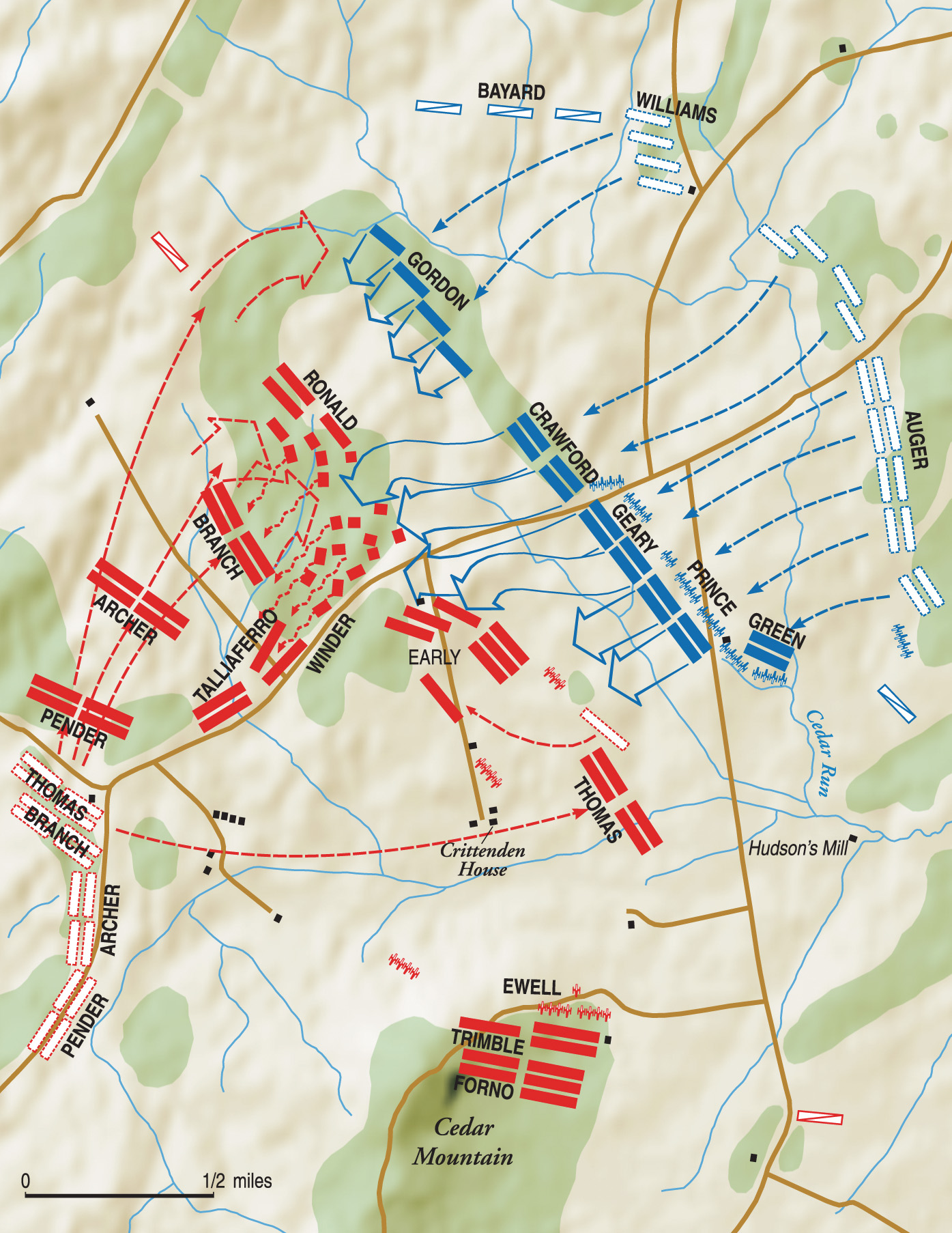

Three-fourths of a mile ahead of the Confederate column, there was a Y-shaped fork where the road to Madison Courthouse departed northwest from the Culpeper Road, which bent to the northeast. Jackson planned an attack. Detached from Ewell, Brig. Gen. Jubal Early would attack along the road, with Winder’s division following behind and to his left. Ewell was to take the rest of his division and sweep far to the right, across Cedar Mountain, and fall upon the Union left. Hill would remain in reserve.

Winder and Early moved ahead as far as the Crittenden Gate. Winder’s men moved into wooded terrain left of the Culpeper Road. As for Early, he led his troops to a position to the right of the Culpeper Road, where there was a wide expanse of open ground on the west side of the mountain. The open vista allowed the Confederates to see Union troops in the distance.

Ewell was fortunate in his position. Cedar Mountain afforded “Old Bald Head” a commanding position for his artillery, which unlimbered high above the enemy guns and troops. What is more, the wooded mountainside offered fine cover for his infantry. The combination of artillery and musket fire could sweep downward into the open terrain northwest of the mountain, where the Union troops were in plain sight. Early, south of the Culpeper Road, was somewhat exposed, but at least he would have a clear view of any approach by the enemy.

But west of the road, the land was largely wooded except for a couple of open fields. At the edge of the fields, the brush quickly transitioned into dense woods. Winder’s regiments would have little warning should Yankee troops burst out of the tree cover and fall upon them.

One mile northeast of Winder and Early, and a mile and a half north of Cedar Mountain, Banks’ two infantry divisions waited on the far side of Cedar Run. Williams’ division was on the right, with Crawford’s brigade ahead and to the right of Brig. Gen. George H. Gordon.

Brig. Gen. Christopher C. Augur’s division held the Union left, with the brigade of Brig. Gen. John Geary brushing against the Culpeper Road next to Williams’ left, and Brig. Gen. Henry Price to the left of Geary. Brig. Gen. George Greene’s brigade, with only two regiments on hand, formed the small reserve.

Among Crawford’s troops, Lieutenant Gould of the 10th Maine saw some horsemen in the distance. “We could not believe they were Confederates,” wrote Gould. “One man especially said they looked ‘too natural’ for that,’ but by and by a puff of smoke and the dull report of a gun convinced the doubters. They were shelling some cavalry, and perhaps it is needless to add that the cavalry were not there by the time that the piece was loaded again.”

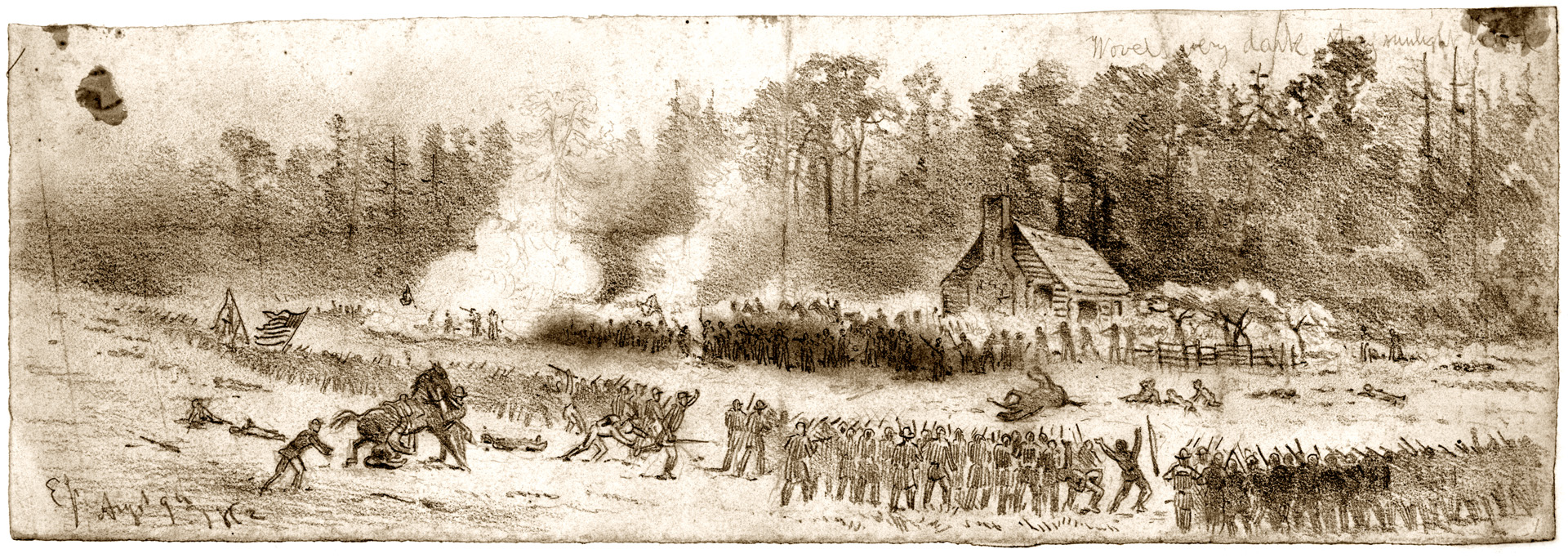

Cannon of both armies opened heavy fire at 2:00 p.m. Shot and shell hurtled over the sun-baked cornfields and meadows. Soldiers on both sides clad in wool uniforms sweated profusely as the temperature hit 98 degrees that afternoon.

Winder arrived with his staff. Taking note of the Federal batteries in the distance to his right front, the general ordered his divisional artillery chief, Captain R. Snowden Andrews, to open up on the Federal artillery with his rifled guns.

Three Confederate guns, two from Captain William T. Poague’s Rockbridge Artillery and one from Captain Joseph H. Carpenter’s Alleghany Battery, replied to the enemy guns from the corner of a field near the Crittenden Gate. All three guns were 10-pounder Parrotts and could easily reach the Federal guns just 700 yards away. Winder joined them, cast off his jacket in the heat, and peered toward the enemy through his field glass to observe effects of his fire.

Union shells soon burst amid the Confederate guns. Carpenter fell with a wound to his head that would later prove fatal. Winder was struck by a shell at 5:00 p.m. that passed between his left arm and side, badly damaging the left side of his chest. He was borne to the rear, where he died at sundown.

Two other officers were wounded by shellfire, and a third was hurled back about 10 feet but escaped serious injury. Oddly enough, despite the fearful toll among the officers, none of the enlisted men handling the three guns were hurt.

About the time Winder was mortally wounded, the nearest Union reinforcements, which were Ricketts’ troops, were several miles to the rear. Banks still believed that he outnumbered the enemy and that a bold push would sweep the Confederates from the field. He construed his written version of Pope’s orders as calling for a quick attack without a delay to await the rest of the army. Roberts’ cutting remark that “there must be no turning back” still stung him. For that reason, even though additional support was still some miles away, Banks ordered an all-out press against the Confederate lines.

Augur’s two brigades under Geary and Prince charged toward Jackson’s right. Their path to the Confederates’ waiting muskets and guns was across an open field, exposing them to “a most deadly fire of grape and canister,” wrote a soldier of the Union Army’s 2nd Maryland Infantry of Prince’s brigade. “Our men reeled and staggered. Whole ranks appeared to be swept down. Our major fell dead. The slaughter was terrible.”

The Confederate brigades of Colonel Alexander G. Taliaferro and Early, arrayed in front of the lane running to the Crittenden House and to the right of Jackson’s location near the Crittenden Gate, received Augur’s attack. Adding to the guns at the gate, more artillery pieces from several batteries had been brought up to support Taliaferro and Early. Prince aimed for Early, while Geary’s advance pressed toward Taliaferro’s men and the guns at the Crittenden Gate.

In Geary’s brigade, Private Henry C. Jacobs of the 5th Ohio charged until the stock of his gun was shattered in his hands by a Confederate shot. In another of Geary’s regiments, George Williams of the 29th Ohio also had his musket shot out of his hands. He picked up another, only to have his replacement musket knocked out of his hands by another enemy bullet. Williams survived the battle to carry off the third musket he fired that day.

Early and Taliaferro, and their protective artillery, fell back 300 yards. Despite giving up some ground, they held their ranks together.

Williams’ division waited after Augur’s attack. They advanced at 6:00 p.m., with Crawford’s brigade in the lead. One of their four regiments, the 10th Maine, had been detached to support the Union center. Gordon’s brigade was held back for the moment, but it eventually would follow in support.

Ahead of Crawford’s three attacking regiments was a wheat-stubble field, 300 yards in width. The field’s eastern edge was the Culpeper Road, beyond which was open country, but the other three sides were bounded by woods. Just beyond the southern edge of the field waited Lt. Col. Thomas S. Garnett’s Virginian brigade.

Garnett’s line was bent at a right angle, with its front facing into the wheat-stubble field and its left turned to face a bit of the Culpeper Road. Garnett’s left and rear were covered by woodland and protected by the guns near the Crittenden Gate.

Crawford asked for a battery to help soften up the Confederates facing him across the field. Before the guns could arrive, a courier from Williams ordered the brigade to advance. Williams did add one of Gordon’s regiments, the 3rd Wisconsin, to support it on its left.

Color Sergeant James Hewison of the 5th Connecticut offered his revolver to his commander, Colonel George D. Chapman. Chapman turned down the offer, telling the sergeant that his life was just as valuable to himself as was his own to him. The colonel led his men into the battle armed only with his dress sword.

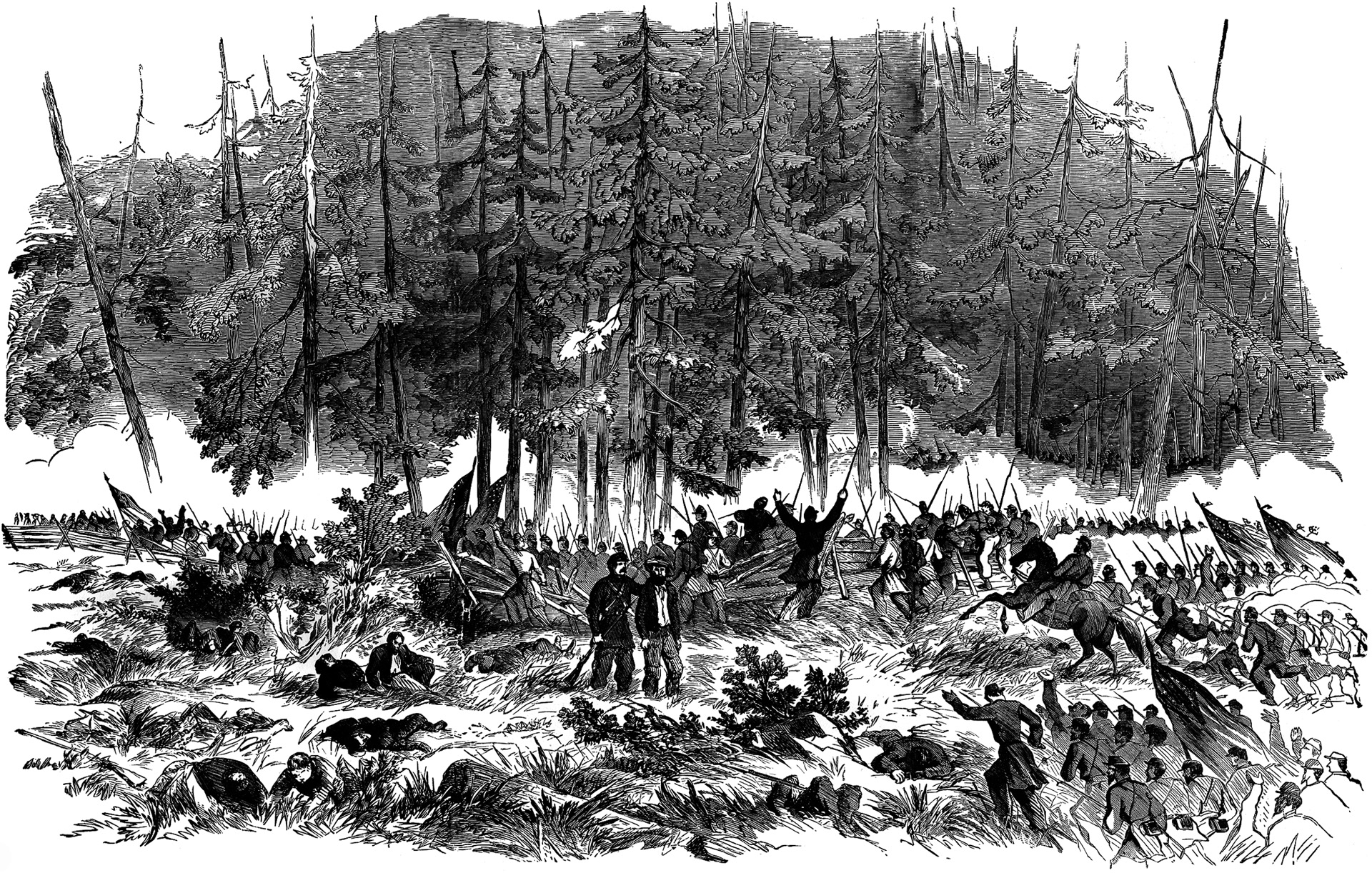

After fixing bayonets, the bluecoats waited by the rail fence marking the boundary of their side of the field. When the order came to charge, they climbed over or pulled down pieces of the fence and “with one loud cheer charged across the open space in the face of a fatal and murderous fire from the masses of the enemy’s infantry, who lay concealed in the bushes and woods,” Crawford wrote.

The Union troops had advanced 50 feet beyond the fence into the field. “The Confederates were shooting into the open and had a fair mark while they themselves were entirely concealed by the tree trunks and foliage of the forest and the fire of our men was, therefore, to a large extent lost, as it was without aim at any seen enemy, but only generally into the edge of the woods,” states the regimental history of the 5th Connecticut Volunteers. The bluecoats closed their thinning ranks and kept advancing toward the enemy.

Many of the bullets aimed at the regimental flags found their marks in the color bearers. Sergeant Hewison, carrying the state colors of his regiment, fell among others of his regiment, but amid the chaos none of his comrades noticed him. One officer of the 5th Connecticut later wrote that seven men fell bearing their national colors.

If the woods concealed the Confederates, the dark depths of brush and leaves also concealed some of Crawford’s men, who had moved into the trees west of the open field. They rushed from the shadowy woods and smashed into the Virginian left flank.

Garnett, who rode to his left when he heard the rising tempo of firing, arrived to see the enemy’s rapid advance. “The enemy in heavy force rapidly advancing, not more than 50 yards from our front, bearing down on us also from the left, delivering as they came a most galling fire,” wrote Garnett. “Unable to withstand this fire from front and flank the First Virginia Battalion gave way in confusion, and rendered abortive every effort of its corps of gallant officers to reform it.”

As the First Virginia Battalion dissolved, Garnett rode to the next regiment in his line, the 42nd Virginia. Garnett ordered the regiment’s commander, Major Henry Lane, to turn his regiment to face its left and block the enemy attack. Moments later, Lane was shot and mortally wounded. By that time, enemy troops were in the rear of the 42nd Virginia and Garnett’s other regiments, where they produced much disorder in their ranks as they fired into them.

Garnett’s 48th Virginia was in a line bent at a right angle, so half faced the open field charged by Crawford and half faced the Culpeper Road. To its right was Garnett’s last regiment, the 21st Virginia, commanded by Lt. Col. Richard H. Cunningham.

Captain William A. Whitcher of the 21st Virginia saw his men in high spirits, as they had just repulsed an advance of a Union regiment, which had burst out of a cornfield, in his words, “to our left oblique.”

“Suddenly and without any warning whatever, a murderous fire was poured upon us from the rear, at least a brigade of the enemy having passed through the woods and reached within twenty or thirty paces of us,” wrote Whitcher.

Cunningham shouted orders to his men. Whitcher could not hear Cunningham’s voice over the roar of battle, but saw his commander gesturing toward a fence to their right. Cunningham was then struck down with a mortal wound. In quick succession the adjutant was captured and three members of the color guard were shot down as the regiment was pushed back. Whitcher, the next-in-command, took control of the regiment. He rallied some of the men 150 paces back from the road.

The Stonewall Brigade, which was led by Colonel Charles A. Ronald, was some distance to the left and rear of Garnett. The veterans of the Stonewall Brigade were also surprised and driven back by the sudden onslaught of the enemy.

Taliaferro’s brigade, to Garnett’s right, had been under cannon fire for some time before Geary’s infantry advanced to within musket shot. While clashing with the Union infantry in their front, the collapse of Garnett’s brigade left Taliaferro’s regiments open to attack from their left and rear by Crawford. Under pressure from three directions, Taliaferro’s brigade fell back deeper into the woods.

Small groups of Taliaferro’s men held together against the Union advance. Lieutenant Henry M. Dutton of the 5th Connecticut, son of a former state governor, died as his regiment fought in the woods. After the battle, a Union burial party later found “the body of Sergeant Alex. S. Avery, of Company G [with] his hands still clasping a gun with bloody bayonet, while around him lay the bodies of five dead Confederates, all slain by bayonet wounds,” according to the regimental history of the 5th Connecticut.

To Taliaferro’s right, the Union tide rushed into the left-flank regiments of Early’s brigade, which also buckled under the same pressure as the other two surprised Confederate brigades.

Fearing that the guns with Taliaferro would fall to the enemy, Jackson sent them to a safe location. While emboldening the bluecoats, the withdrawal of their guns loomed as an omen of disaster to the Confederate foot soldiers. Jackson decided on a spectacular gesture to rally his men. For the first time during the war, he reached to draw his sword. Unfortunately, it had been so long since he last took out his sword, the blade was rusted fast inside the scabbard. Unable to tug the blade free, Jackson detached the scabbard from his sword belt. He flourished the scabbard and sword overhead.

“Rally, brave men, and press forward!” he shouted. “Your general will lead you! Jackson will lead you! Follow me!” Although Taliaferro stopped Jackson from leading a charge, scores of men found new hope as the general flourished his scabbard high above his head, and a growing core of soldiers rallied to hold their position.

By this time, the lead elements of Hill’s division, which had seven brigades rather than the usual four, were streaming into the front lines. Crawford’s regiments were stalled in the woods. “The support I looked for didn’t arrive,” he wrote. The Union attack, successful as it had been so far, came with a heavy cost. Many of the bluecoats were already left behind, fallen in the field or further along during their surge into the woods.

As the 5th Connecticut plunged deeper into the woods, Lt. Col. Henry B. Stone shrugged off a minor wound. Another shot struck him in the thigh. His men thought that he was fatally wounded and left him propped against a tree. Stone lived long enough to be taken prisoner, but would die in captivity.

Crawford’s advance was nearing its crest, as the bluecoats swung toward their left toward the open ground along the Culpeper Road. A Confederate flag bearer was shot down, and several Union soldiers sprinted toward the fallen banner. Captain William W. Bush of the 28th New York was seen picking up the captured flag.

When the dwindling Federal force pushed deeper into the tree cover beyond the stubble field, the Stonewall Brigade fell back until they met Hill’s troops marching to the front. After the arrival of reinforcements, the brigade reformed and joined with Winder’s old regiments and Hill’s corps to continue the battle. The brigades of Garnett, Taliaferro, and Early reformed to retake their lost ground. With thousands of fresh troops added to the array against them, the Union soldiers began falling back with appalling losses.

Every one of the field officers in the 5th Connecticut, the 28th New York, and the 46th Pennsylvania were dead, wounded, or fell into enemy hands. Over half of the line officers in those three regiments were either hit or captured. Captain Bush, who minutes before had achieved the goal of capturing an enemy flag, was among the prisoners.

Sergeant Hewison recovered a bit from the shock of his bullet wound. He came to amid dead or badly wounded men, but still in possession of his flag. He tore the colors from the staff and wrapped the bright cloth around his body under his jacket, and crawled away on his hands and knees. When fellow Federals found him and bore him away safely to seek medical attention, he still had the salvaged flag with him.

Colonel Chapman was briefly taken prisoner and freed. As his regiment fell back to the edge of the woods before the blood-spattered field they’d crossed at such great cost, the colonel was captured once again. Among some of his men nearby arose the cry, “Let’s recapture him, there’s but few Rebs around him.” Nearly two dozen men rushed to save Chapman, but the valiant group was overwhelmed by the sudden appearance of more Confederates. The colonel stayed in enemy hands until he was exchanged a few months later.

When the 10th Maine came under fire from different directions by multiple Confederate regiments, Gould noted the variety of noises made by the enemy bullets. From some Confederate muskets came “the fierce zip of the swift Minie bullet,” he recalled. Even more common than the sound of the Minie bullet was “the singing of slow, round balls and buck shot fired from a smooth bore, which does not cut or tear the air as the creased ball does,” he wrote. “Each bullet, according to its kind, size, rate of speed, and nearness to the ear made a different sound. They seemed to be going past in sheets, all around and above us.”

Brig. Gen. Lawrence O’Brien Branch, who led the vanguard of Hill’s division, halted for some moments near the front. He was followed closely by Brig. Gen. James Archer’s Tennessee brigade, which would go into line on his left. Branch had served three terms as an antebellum congressman from North Carolina.

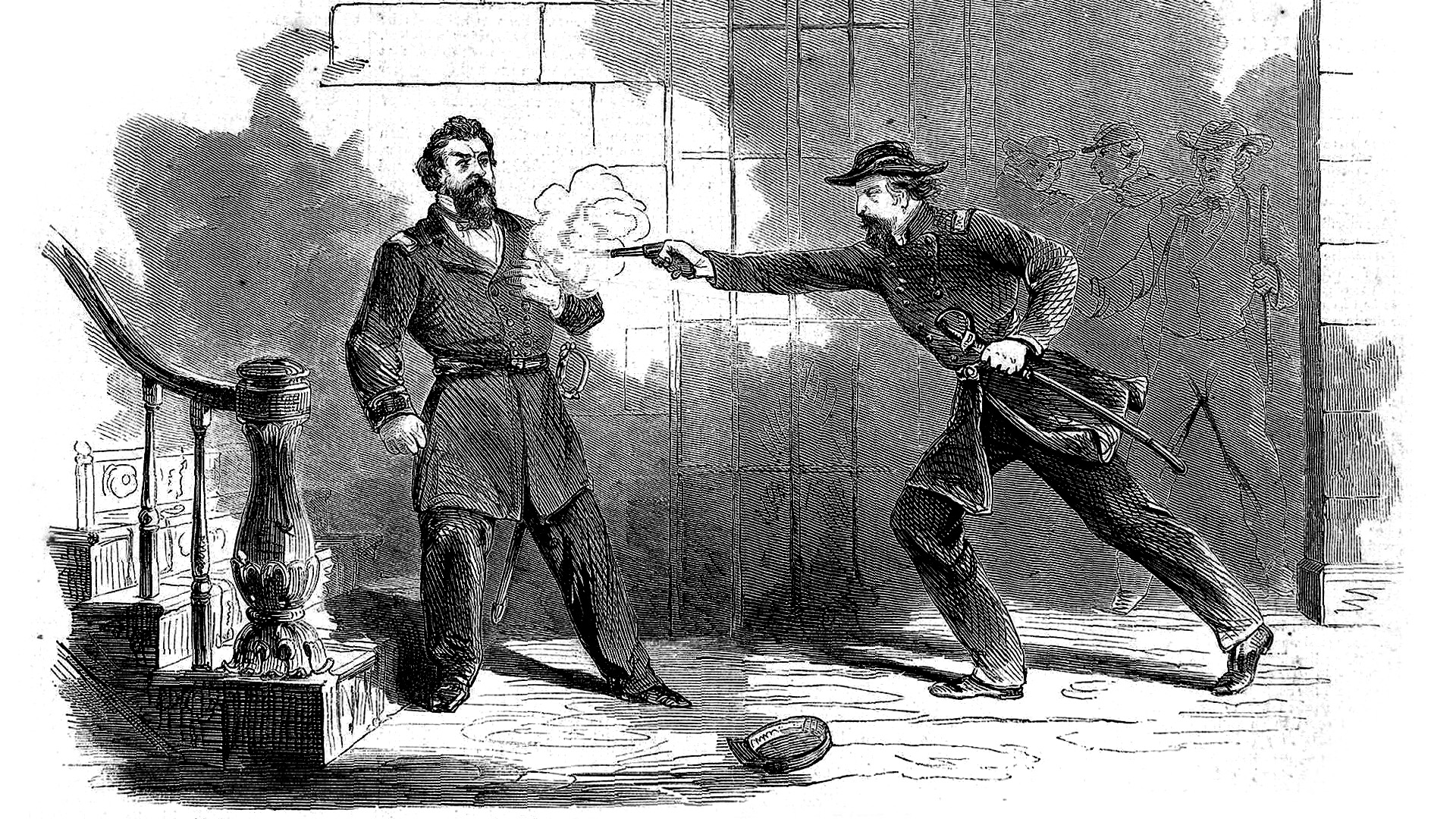

Confederate troops pressed forward into the chaos engulfing Banks’ crumbling army, surrounding and capturing isolated Federal units. Both Augur and Geary were wounded. Corporal John M. Booker of the 23rd Virginia grabbed the bridle of a Union officer, thereby making a prisoner of Prince. The high-ranking prisoner was taken to Powell Hill. “General, the fortunes of war have thrown me in your hands,” Prince said. Bullets hissed and buzzed through the air around them. “Damn the fortunes of war, General!” Hill snapped. “Get to the rear! You are in danger here!” Prince would remain a prisoner of the Confederacy for four months.

Calling up Greene’s small reserve force made little difference in the overwhelming odds facing the Union troops. Banks gave in and withdrew his infantry at 6:30 p.m., which fell back in good order. To buy some time, Bayard ordered a desperate charge by Major Richard I. Falls and the 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry. Falls had just 175 men on hand, but they plunged in among the Confederates, causing for a brief time considerable chaos before they were forced to fall back. 30 of Falls’ men were killed or wounded. Falls’ horse was shot from under him, and so many of the regiment’s horses were shot down that fewer than 75 men were able to ride back.

The 10th Maine exchanged volleys with the advancing enemy. “The sun had set and the smoke had settled like a thin mist over the entire field of battle,” wrote Gould. “We could see, too, the blaze of the enemy’s muskets instead of the puff of smoke which one observes in broad daylight. Over these dark and smoky woods was the bright sunlight dazzling our eyes and adding another drop to our bucket of disadvantages.”

The last light of day faded as Banks retreated, with victorious Confederate troops following at his heels. “The landscape itself was “as romantic as hell, [with] a full moon which disclosed the dark shadows of the woods and threw a dreamy light over the landscape,” Gordon overhead a staff officer remark.

Some of Crawford’s men thought they were safely away and halted to build campfires in the moist, cool grass of a clover field, according to newspaper reports. Confederate gunners were still in range, though. Firing at the distant, twinkling campfires, the Confederate artillerists broke up the idyllic evening respite and drove the exhausted Yankees further along into the night.

Confederate cavalry surprised Pope and his generals as they tried to manage the retreat. Gordon remembered the enemy riders bursting from the woods 30 yards from them.

The bullets hissed through the bushes, sparkled in the darkness as they struck the flinty road, or singing through treetops, covered Pope and his officers with leaves and twigs,” Gordon wrote. Banks “was struck by the forefoot of an orderly’s horse as the animal reared from fright [and suffered] a severe confusion.” Mounting quickly, the generals and their staff officers galloped toward Culpeper.

Adding to the combined dangers of enemy troops and the darkening night, a Union battery half a mile to the rear opened fire. “Plump in our midst came the friendly shells,” continued Gordon, who escaped injury when a shell exploded “so nearly under my horse that I have never been able to tell whether it was to the right or the left of a plumb-line through his belly.” Officers shouted for someone to put a stop to the friendly fire, and an aide rode to the battery and halted its fire before they killed one or more of their own generals.

Confederate pursuit did not continue for long. Too late to affect the battle, Ricketts and Sigel had moved forward in support of Banks. Once Jackson learned of the arrival of Union reinforcements, the risky prospect of continuing the battle in the dark did not appeal to him, and he ended the active pursuit of the Yankees.

Cedar Mountain was one of the rare battles when Confederate troops outnumbered their enemies; on this occasion, by slightly more than two to one. Banks’ 8,000-man corps lost 2,253 men, including 314 dead, 1,445 wounded, and 594 missing and captured. Crawford’s brigade alone suffered 867 casualties, which was more than one-third of the day’s total. As for Jackson’s wing of Lee’s army, it suffered 1,338 killed, wounded, or missing.

The Confederates lingered on their hard-won battleground for three days, after which they withdrew to Gordonsville. If the clash won no direct benefits for Jackson, it certainly dampened Pope’s prospects for a successful campaign.

Halleck ordered Pope to halt his advance on Gordonsville. Pope’s Army of Virginia stayed inactive for many days, which allowed Lee ample time to gather his army and bring it north. In this way, Cedar Mountain set the stage for the Confederate victory at Second Manassas on August 29-30. That decisive victory paved the way for the Confederate invasion of Maryland and the war’s single bloodiest day, which occurred on September 17 on the bank of Antietam Creek, when Lee once again battled Maj. Gen. George McClellan at the head of the Army of the Potomac.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments