By Al Hemingway

Pfc. Clayton Jay of Lamesa, Texas, was watching the sunrise from the attack transport Zeilin in the early morning hours of November 19, 1943. The weather had been ideal for the Marines since they left New Zealand days earlier. However, Jay knew this would be the last peaceful moments that he and his fellow Leathernecks would experience aboard ship. Tomorrow his unit, Company F, 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, 2nd Marine Division, would attack the tiny island atoll of Tarawa, which its Japanese defenders had turned into a defensive bastion. The operation had been dubbed “Galvanic” by the high command.

With the seizure of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, was already eyeing the next objective in his island-hopping campaign to defeat the Japanese—the Gilbert Islands. “With the paucity of carriers—and the urgency to get started on our return march to the westward—it was essential we seize Tarawa,” said Nimitz, “first, so that we could use it as an unsinkable carrier in our operation against the Marshalls, and second, to eliminate Tarawa as a threat to our important line of communications between our West Coast and Australia and New Zealand.”

The naval force used to assault Tarawa, the Fifth Fleet, was enormous, consisting of six attack carriers, five light carriers, seven escort carriers, 12 battleships, 15 cruisers, 65 destroyers, 33 transports, 29 LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks), and another 28 support ships. Also, there were 35,000 soldiers and Marines, over a hundred thousand tons of cargo, and 6,000 vehicles.

In command of this vast armada was Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, known as “Sprew” to his Naval Academy peers. He selected Rear Adm. Harry W. “Handsome Harry” Hill to command Task Force 53 for the assault on Tarawa. They immediately flew to New Zealand and conferred with the Marines. Spruance’s orders were simple: Prepare for an assault on Tarawa.

Intelligence had disclosed a new Japanese airstrip on Betio Island, the main island in the atoll, guarded by units of the Japanese Special Landing Forces, erroneously referred to as “Japanese Marines.” In all, 5,000 enemy troops defended the diminutive island. They consisted of elements of the 3rd Special Base Force, 7th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force, the 111th Pioneers, and the 4th Construction Unit.

Rear Adm. Tomanari Saichiro, who had a reputation for being an excellent engineer, was in charge of constructing fortifications for Betio. The Japanese strategy was to delay the Marines at the beachhead until they could be annihilated before they reached inland.

Betio was approximately three miles in length and about 800 yards at its widest point. The island had no vegetation to speak of and was flat with no elevation higher than 10 feet above sea level. Saichiro had his workers construct a log and coral barrier, or “seawall,” surrounding almost all of Betio. The island also boasted 500 pillboxes, tank traps, 8-inch guns, howitzers and artillery, heavy machine guns, light machine guns, and “knee” mortars. This impressive array of firepower spurred one Japanese officer to remark: “A million Americans couldn’t take Tarawa in 100 years.”

Historian Samuel Eliot Morison commented on the island’s defenses, “No military historian who viewed Betio’s defenses could recall an instance of a small island having been so well prepared for an attack. Corregidor was an open town by comparison.”

The irascible Lt. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith was put in command of V Amphibious Corps. For the arduous task of seizing Betio, he selected the 2nd Marine Division under Maj. Gen. Julian C. Smith. Spruance also directed the U.S. Army’s 165th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) of the 27th Division to capture Makin Island, also in the Gilberts, at the same time the Marines were capturing Tarawa.

For the invasion of Tarawa, Lt. Col. David M. Shoup, 2nd Marine Division Operations officer, devised a plan that included a preliminary bombardment, capturing nearby Bairiki Island and utilizing it for artillery support, and a feint landing to fool the Japanese.

“Howlin’ Mad” Smith met with all the top officers for Operation Galvanic and briefed them on the plan. However, Smith and his staff were in for an unpleasant surprise. First, Nimitz restricted the naval bombardment to a mere three hours prior to the Leathernecks hitting the beach. Second, the Bairiki invasion was cancelled. Nimitz feared an enemy naval attack and wanted to keep his forces concentrated. Also, to the utter dismay of Julian Smith, “Howlin’ Mad” Smith selected the 6th Marines as his corps reserve. The usually unflappable commander was shocked. His division would be attempting a frontal assault on the heavily defended beachhead with very little naval gunfire support. In addition, without his 6th Marines, he had a mere two-to-one advantage in troop strength. This was in direct opposition to the amphibious doctrine the Marines had honed prior to World War II.

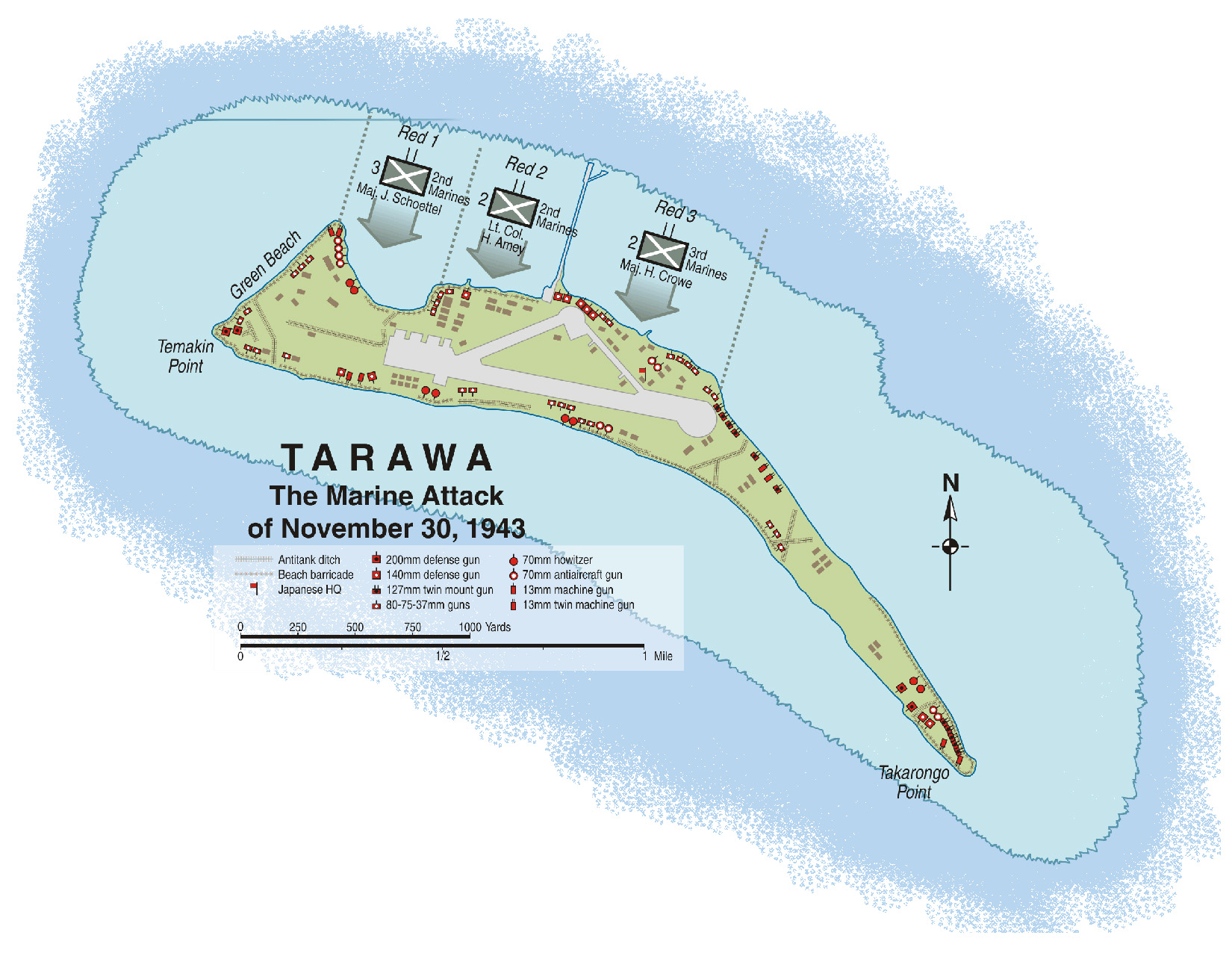

Shoup hastily altered his plans. Since the enemy had fortified themselves on the southern and western portions of the island, he opted to have the 2nd Division land on the northern coast. Each landing area was 600 yards long. In the end, he selected the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, commanded by Major John F. Schoettel, to land on Red Beach 1; next on Red Beach 2 would be the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, led by Lt. Col. Herbert R. Amey, Jr.; and, lastly, on Red Beach 3, Major Henry P. Crowe’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines would disembark. The remainder of the 8th Marines would be held back as division reserve, while the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines were regimental reserve.

As D-day drew near, a meeting was held to discuss the last-minute details of Operation Galvanic. One U.S. naval officer remarked about the still-touchy subject of naval gunfire support: “We do not intend to neutralize the island, we do not intend to destroy it, gentlemen, we will obliterate it.”

However, the quick-tempered “Howlin’ Mad” was swift to reply. “Even though you naval officers do come in to about 1,000 yards, I remind you that you have a little armor,” he snapped. “I want you to know the Marines are crossing the beach with bayonets, and the only armor they’ll have is a khaki shirt!”

As the enormous fleet steamed its way toward Tarawa, Colonel William Marshall, the commanding officer of the 2nd Marines, fell ill. Julian Smith turned to the one qualified person he knew could take charge on such short notice: David Shoup. With a promotion to full colonel, he quickly took command.

In the early morning hours of November 20, 1943, the Marines of the 2nd Division began their slow descent from the nets to their awaiting transports. Aboard Zeilin, the Leathernecks inched their way down the cargo net to the sound of the Marine Corps Hymn. Pfc. Clayton Jay got in his amphibious tractor, LVT-44, and watched as the ships commenced their barrage of Betio. “It was a beautiful sight,” he wrote later. “As the big guns fired, flames would shoot out 20 feet. I wish some artist could have captured that sight.”

Joining in the massive bombardment were the battleships Maryland, Idaho, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, New Mexico, Mississippi, and Colorado. The Japanese 8-inch “Singapore guns” hit close to the fleet. For the next three hours, naval gunfire, together with the carrier planes of Task Force 50 from Essex and Bunker Hill, kept up a sustained pounding of Betio’s defenses. A lieutenant commander aboard the cruiser Baltimore later said: “One could see coconut palms shooting up into the air, the trunks being separated from the foliage and the tops coming down like shuttlecocks.”

At approximately 8:55 am, Admiral Hill called for an end to the bombardment. Julian Smith and his chief of staff, the legendary former Raider Colonel Merritt A. “Red Mike” Edson of Guadalcanal fame, protested vehemently. The assault craft were still 4,000 yards from the beach. Hill insisted, thinking the heavy smoke from the guns obscured the island, making it unsafe for overhead fire support for the assaulting Marines.

A sailor on the destroyer Ringgold watched the awesome barrage and exclaimed: “The whole island was ablaze. You couldn’t see anything but fire and smoke. Every once in a while a great pillar of flame shot skyward as though a volcano had erupted. A sailor standing next to me gave me a sickly grin. ‘Mate, they need foremen in there—not Marines.’ And I thought, ‘It’s going to be a cinch for our guys—they’ll find nothing but splintered palm trees and dead Japs.’”

Unfortunately, both men were wrong. The Japanese on Betio were dug in deep—and waiting for the Marines to come ashore. As overpowering and devastating as the naval gunfire had been, it had not softened Saichiro’s fortifications. In addition, Hill’s order to halt the bombardment while the assault craft were 4,000 yards from the beachhead had given the enemy enough time to transfer troops quickly, shoring up the northern beaches where the 2nd Division was preparing to land. Some of the enemy emerged from their bunkers incoherent, with blood streaming from their ears, noses, and eyes. However, they were still full of fight. Some manned their weapons wearing nothing but their sennimbari, the “belt of a thousand stitches,” sent to them by women back home. Supposedly, the belt had magical powers to ward off bullets. The Japanese defenders would need more than a cloth belt to escape the tremendous U.S. firepower poised offshore.

As the LVTs, dubbed Alligators, and other landing vessels neared shore, the steady crack of small arms and automatic weapons fire began to increase in intensity. An area dubbed “The Pocket” by the Marines was most grueling. Between Red Beach 1 and Red Beach 2, the Japanese had concentrated a good number of their automatic weapons and artillery. The thinly skinned LVTs in the first waves could not withstand the punishing fire. Many of the coxswains, trying to maneuver the small Alligators, were killed or wounded instantly.

Leathernecks from the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines hitting Red Beach 1, in an area called the “Bird’s Beak,” were caught in a murderous crossfire. Many of the infantrymen had to wade ashore when their assault craft became stranded on a coral reef, which impeded progress toward the beaches. Company L suffered a staggering 35 percent casualties before even stepping on land.

Captain William E. Tatom, commanding officer of Company I, peered over the bulkhead of his LVT trying to get his bearing and find his platoons to organize them on the beach. Suddenly the Marine officer was thrown backward, landing with a thud on the troop deck. He had been shot through the head. In a matter of minutes, 17 of the battalion’s 37 officers had been killed.

Corporal Norman S. Moise of Company A, 2nd Amtrac Battalion was thrown on the deck of his craft when a Japanese shell struck the vehicle. “I do not know how long I was there before another Marine came on board,” he wrote years later. “He was bare to the waist…. His left shoulder blade was missing. His heart was exposed, and I watched it pump. He asked if I had a drink, I looked around. There was nothing in the cargo compartment. I did, however, see a can of fruit juice and a canteen in the driver’s compartment. I reached the canteen and pushed it to him. He drank from it and thanked me.”

The Marines attempting to land on Red Beach 2 were also being pounded unmercifully by the hidden defenders. Especially dangerous was the re-entrant between Red 1 and Red 2. Company E had five officers killed almost immediately. Survivors of Company G managed to hunker down at the seawall in the center. Scrambling to get to the seawall for some protection from the enemy’s guns, Company F lost 50 percent of its manpower.

Staff Sgt. William Bordelon of San Antonio, Texas, had survived the murderous trek across Tarawa’s unforgiving reef. Once ashore, the combat engineer from Company C, 1st Battalion, 18th Marines quickly destroyed two enemy bunkers. Although hit in the arm, the tough NCO returned for another load of TNT and neutralized a third pillbox. Taking cover, he leaped into the water to pull wounded Marines to the relative safety of the seawall. Once more, the hard-nosed Texan commandeered another satchel charge of explosives and destroyed a fourth bunker. Although wounded again, Bordelon was scaling the seawall for a fifth time when he was gunned down by a Nambu machine gun. For his exemplary bravery on D-day, he would be awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously.

“Our tractor was about 25 yards or so from the beach when the corporal sitting next to me was struck by enemy fire,” recalled Pfc. Jay. “He slumped over on me with half his head gone.”

Jay’s Alligator churned its way slowly forward until it rested upon the seawall. Without warning, a Japanese shell found its mark. The scene was described as a “slaughterhouse,” as everyone who was alive tried to crawl from the metal death trap. A young private was hit in the mouth, blood gushing from his wound, as he tried to emerge to find safety.

“The rest of us dove out the back of the tractor, running around the side of it to the seawall,” continues Jay. “I had a chance to look around. I hope I never see that sight again. Bodies of Marines were floating in the ocean and on the beach. I realized how lucky I was. As I looked behind me I could see Marines wading in, rifles above their heads, being cut down by the Japs’ small arms fire. It was awful. Blood from the dead actually turned the water a bright crimson red.”

Suddenly, Jay felt a sharp pain in his right leg as shrapnel from an exploding shell hit him. Despite the pain, the Texan, his squad leader, and other Marines tossed hand grenades and blocks of TNT to neutralize a Japanese gun emplacement. Advancing about 25 yards, Jay found shelter in a foxhole with two dead Japanese soldiers. Looking around, he was startled to see one of the enemy infantrymen moving. Apparently the shelling had just knocked him unconscious. Without hesitation, Jay wheeled around and shot him.

Leaping from the hole, Jay kept advancing inland to link up with the remainder of his company. As he ran forward, a burst of automatic weapons fire hit his squad leader, spinning him around, almost ripping him in half. “He was a great guy,” Jay later remembered. “He was a veteran of the Guadalcanal campaign. Always had a smile for you.” Angered because of the death of his squad leader, he crawled toward the machine-gun nest and emptied his M-1 Garand into the enemy defenders.

On Red Beach 3, the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines were having a tough time as well. The battalion commander, Major Henry Crowe, was a “tower of strength” on Betio. When his boat slammed into the reef, he hollered for all hands to get out and head for the beach. Wading through several hundred yards of knee-deep water, Crowe kept pushing his men. “Look,” he yelled, “the sons of bitches can’t hit me. Why do you think they can hit you? Get moving.”

Crowe’s Marines had landed in front of the island’s more formidable defenses. Fortunately the Leathernecks had continuous fire support from the destroyers Ringgold and Dashiell. As the destroyers lobbed their 5-inch shells at the enemy, the infantrymen on Red 3 were able to gain a small foothold.

Watching the entire scene from his Vought OS2U Kingfisher floatplane, Lt. Cmdr. Robert McPherson later remembered: “The water never seemed clear of tiny men, their rifles held over their heads, slowly wading beachward. I wanted to cry.”

As the main assault battalions were clawing their way onto Betio, Lieutenant William Hawkins and his 34-man Scout-Sniper platoon stormed a 750-foot pier between Red 2 and 3, accompanied by combat engineers. Their LVT immediately came under horrific fire from the Japanese. The machine gunner poured .50-caliber fire as the tractor attempted to maneuver itself closer to the pier. When the gunner was torn apart by enemy fire, Hawkins himself jumped on the weapon, raking the Japanese fortifications. He eliminated six machine-gun emplacements in spite of the bullets cracking all around him.

Within six minutes, Hawkins and nine other Marines had destroyed the pier. In the process, they had also killed 25 Japanese. However, as soon as the assaulting Marines departed, other enemy troops moved in to retake the positions.

When Colonel Shoup’s craft ran aground on the reef, he and Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson, a former Marine Raider, quickly jumped on another available LVT. On the third try, the LVT finally made it to shore before it was badly damaged by enemy shelling. In the interim, Shoup was peppered with shrapnel in his leg. He managed to hobble from the tractor and find shelter near the seawall. From this point, the indomitable officer established his headquarters. Amid the deafening roar of Japanese fire and the stench of dead Marines floating in the ocean, Shoup tried desperately to gain communications with the other units and the ships offshore, especially Maryland, where Julian Smith was watching and listening to the battle.

Sherman tanks were also attempting to gain access to the island to give the beleaguered Leathernecks much-needed fire support. As the clanking vehicles tried to push inland, their guides were cut down by murderous fire.

The combat engineers created openings with satchel charges, but the bodies of dead Marines blocking the entrance forced the tank commanders to try an alternate route. At the end of the first day of combat, only two of the 14 tanks to successfully get ashore were still operational.

By late morning, the 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines and the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines were making their way to the beachhead. As their landing craft neared the reef, an ear-shattering explosion was heard. A Japanese 5-inch coastal gun had zeroed in on the six waves of Marines, and in one blinding flash two boats were gone. Coxswains, frightened by the sickening sight, ordered the Marines off. As the ramps lowered, infantrymen, weighted down by heavy equipment, disappeared from sight, drowning quickly. Survivors managed to swim ashore. Boats eventually rescued others. An estimated three-quarters of the machine-gun platoon of Company I was lost. It was a devastating blow. “They were pulverized before they got ashore,” remarked Pfc. Rick Spooner. “Those poor guys were dropping in bunches.”

By late afternoon, “Howlin’ Mad” turned the 6th Marines over to Julian Smith’s control. However, Smith had no idea where to land them without getting the battalion “chewed up.” He was in a precarious position.

D-day did have one major bright spot. Major Michael P. Ryan, commanding the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, had breached the Japanese defenses and penetrated 500 yards aided by a pair of M4-A2 Sherman tanks. However, his gain was short-lived. Ryan pulled back before nightfall to consolidate his lines.

As night crept over Betio, the Marines had a shaky foothold on the tiny island. The 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines were situated on two small beaches in the center. To the east, remnants of the 8th Marines held a perimeter on Red Beach 2 about 700 yards long and 300 yards deep. About 800 yards to the west, the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines had seized the island’s northwest corner on Red Beach 1 and Green Beach. Shoup later confessed in a message to Julian Smith, “The situation does not look good ashore.”

Throughout the long, black night the Leathernecks kept a watchful eye for an expected Japanese Banzai attack, an all-out suicide charge. However, to their relief, none came.

As dawn broke on D+1, Betio, in the words of one Marine officer, “looked like a charnel house.” The odor of decaying bodies filled the tropical air. Of the 5,000 Marines who had landed on Betio that day, nearly 1,500 were dead or wounded.

The Leathernecks of the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines who had been circling off shore for the past 18 hours, were finally given the word to land. Unfortunately, the tides did not allow adequate water for the craft to cross the reef. The Marines were exposed to terrible enfilading enemy fire. It was a disaster.

Shoup immediately called for naval gunfire. The 75mm howitzers of the 10th Marines opened up to give the infantrymen support. Famed combat correspondent Robert Sherrod later wrote: “One boat blows up, then another. The survivors start swimming for shore, but machine gun bullets dot the water all around them. This is worse, far worse than it was yesterday.”

Pfc. James Collins later said: “All around me men were screaming and moaning. I never prayed so hard in all my life. Only three men out of 24 in my boat ever got ashore that I know of.”

Without hesitation, Shoup ordered all units on Red Beach 2 to begin their assault on the Japanese defenses in their sector in hopes of taking some of the pressure off the besieged Marines trying to scramble ashore.

Lieutenant Hawkins and what was left of his Scout-Sniper platoon swung into action. He and his men made numerous assaults into “The Pocket” on Red Beach 2. As combat engineers destroyed Japanese pillboxes, Hawkins raked the area with his .45-caliber grease gun. When he was hit in the shoulder, he was urged to evacuate. He steadfastly refused even though he had been wounded the previous day while taking the pier. He personally took out three additional pillboxes before being killed by a shell fragment. He would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary bravery.

On the western portion of Betio, Major Ryan’s Marines were able to mount a concentrated attack against the enemy’s fortifications in their zone. He was able to communicate with two destroyers which immediately pounded Japanese pillboxes so the Leathernecks could make their advance. Although hampered by poor communications, Ryan’s men had seized all of Green Beach. By using one operable radio and a relay team of runners to inform Shoup of his movements, the resolute officer was ready to push ahead.

By midafternoon on D+1, the mood on Tarawa was improving. Marines were beginning to push slowly inland and taking ground from the enemy. The guns of the 10th Marines and flamethrowers of the 18th Marines were adding more punch to the Marine arsenal during a battle that had been fought by predominately small arms fire to this point.

With the introduction of the 6th Marines into the fray, the tide definitely turned. Colonel Shoup was confident enough by late afternoon to relay a message to Julian Smith. He wrote: “Casualties: many. Percentage dead: unknown. Combat efficiency: We are winning.”

Pfc. Clayton Jay had survived the first night on Tarawa. He had been ordered off the island after an officer had witnessed him limping. He had his wound bandaged by a corpsman, but once “out of the officer’s sight,” he moved back into the line. However, his leg stiffened up and he could no longer walk. The stubborn Texan was evacuated from Betio to a hospital ship offshore. He would spend the next two months in the hospital recuperating from his wound, but he had survived 36 hours in the living hell of Tarawa.

By late afternoon, Lt. Col. Ray Murray’s 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines landed on Bairiki. The only opposition was one lone machine-gun emplacement. An airstrike by Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters off the carriers struck a drum full of gasoline that was in the Japanese pillbox. Within minutes, the fortification and its inhabitants were ablaze. With the immediate threat eliminated, Lt. Col. George Shell’s 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines came ashore. By morning, they were setting up their guns to give support to the Leathernecks on neighboring Betio.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines landed relatively unscathed with the exception of one LVT that hit a mine. Major William K. Jones, battalion commander, quickly hooked up with Ryan’s tired men and assumed a defensive posture for the evening.

“Red Mike” Edson also slipped ashore that night to take over command from the exhausted Shoup. The feisty Marine officer had certainly done a magnificent job in the face of such horror. He had commanded eight battalions to victory on Tarawa, and for this he would receive the Medal of Honor.

On November 22, D+2, Company C, 1st Battalion, 6th Marines stepped off to continue the attack. With support from three light tanks and one medium tank named “China Gal,” the Leathernecks moved down a corridor as wide as a football field, bristling with pillboxes and bunkers.

Jones’s men moved quickly and by late morning had made contact with the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines. “These infantrymen were terrific,” recalled Lieutenant Edward Bale, commanding China Gal. “I never saw such guts. We ranged across the whole end of the island and down the south side and they never flinched but took us straight to the targets.”

On Red 2, the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, using satchel charges and Bangalore torpedoes, eliminated Japanese strongpoints. Other defenses were more difficult to neutralize. The 37mm guns of the light tanks were useless, but the heavier 75s managed much better.

By late in the day, a small enemy raiding party attempted to breach the Marine lines but was discovered. Excited to see their adversaries finally exposed, Marine riflemen wasted no time in killing every attacker.

Elsewhere, Crowe’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines and elements of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines were also locked in combat. Company F was engaged atop an immense steel, bombproof pillbox. The Leathernecks utilized every weapon they could muster, but still the determined enemy would not surrender. Suddenly a 60mm mortar shell ignited an ammunition dump. Without hesitation, a medium tank was able to close in and belched several 75mm rounds into the steel pillbox, putting it out of action.

Historian Michael B. Graham, in his book Mantle of Heroism, wrote: “The mammoth, sand-covered dome, so formidable for these past three days, was now isolated. The nearby supporting positions all had been knocked out. The trenches were nearly empty of live enemy riflemen; the bunkers were torn from their foundations by naval gunfire; the pillboxes were burned, blasted, cracked open, and buried by sand.”

With that, Major William Chamberlain, executive officer for 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, led the charge. Right behind them were 1st Lt. Alexander “Sandy” Bonneyman and Sergeant Alfred E. “Pappy” Coleman of the 18th Marines, tossing fused charges. Other combat engineers poured diesel fuel down the ventilation shafts.

Without warning, the occupants poured from the pillbox like a pack of angry hornets. As the enemy soldiers raced to the top of the position, Bonneyman began picking them off to give the engineers time to finish their task. As he was putting another clip into his M-1, he was cut down by enemy fire. Marines from companies F and G moved into the firefight and began killing the remainder of the enemy. Bonneyman would receive the Medal of Honor posthumously.

As night fell, the Marines tried to consolidate their lines and kept a constant vigil for the nocturnal raids of the Japanese. At about 1930 hours, an enemy probing action took place.

Suddenly the inky blackness was shattered by the all-too-familiar cry of “Banzai,” and 50 Japanese stormed the lines between companies A and B of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines. The sky was bathed in an eerie light from the flares as the Leathernecks opened up on the charging enemy. Lieutenant Norman K. “Hard Tom” Thomas, commanding Company B, called the command post (CP) and radioed Major Jones for help. To his dismay, he was informed to hold at all costs or the “entire battalion would be lost.” There was no help for him.

Thomas’s Marines managed to beat back the attackers. However, the determined enemy hit their lines again several hours later. The fighting was intense. One Japanese soldier, well over six feet in height, sprinted toward Thomas. In the ensuing scuffle, the Marine officer finally wrestled the attacker to the ground, drew his .45-caliber pistol, and “finished him off.”

As the enemy broke off the attack, the destroyers Sigsby and Schroeder kept firing. The pack howitzers of the 1st Battalion, 10th Marines expended 1,300 rounds. When it was over, the Marines had sustained 45 dead and 128 wounded. The Japanese lost 325 killed.

Major Jones, surveying the perimeter at first light, saw dead bodies, Marines and Japanese, entwined, “stacked four and five deep.” The weary Thomas later commented on the heroism of his Marines: “Every damn one of them is a champion.”

The fourth day on Betio saw Lt. Col. Kenneth F. McLeod’s 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines arrive on the island to assist the fatigued infantrymen. With the help of the combat engineers and armored support, the Leathernecks moved swiftly to crush the remaining Japanese. By the afternoon, McLeod’s battalion had pushed its way to the eastern end of Betio.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines and the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines were also pressing forward. By now many of the stunned defenders were killing themselves to avoid surrender. Engineers and tanks were taking pillboxes and bunkers in quick order. By late that afternoon, the major fighting on Betio was over. All that remained was the obligatory mopping up to eradicate the last pockets of Japanese defenders.

Admiral Harry Hill, accompanied by his staff, toured the island and marveled at the seemingly impregnable fortifications the Marines had encountered. They concluded that the Navy would have to reevaluate its preliminary bombardment strategy for future island campaigns.

A somber “Howlin’ Mad” Smith also visited the island, which was now being called “the Tarawa killing ground” by war correspondents. He was visibly shaken when it was reported to him that the casualties could reach as high as 3,000. On completion of the Marshall Islands campaigns, he said: “[The] recommendations made and acted upon as a result of the Gilberts offensive proved sound.” Still, the sight of so many dead Marines, their lifeless bodies washing ashore or floating out to sea, would be permanently etched in his mind.

At midday on November 24, Pfc. James L. Williams bugled “Colors” as the Stars and Stripes were hoisted for the first time on Betio. All eyes were turned toward the flag as it slowly inched its way to the top of the flagpole. Tarawa was declared officially secured.

The cost to take tiny Betio was staggering. The Marines lost 3,407 killed, wounded, and missing. The Japanese fared much worse, losing nearly 5,000 of their troops. Only 17 Japanese survived the brutal fighting. All of this occurred in a mere 76 hours.

Despite all the negative reporting on the battle because of the high casualties, Admiral Nimitz declared: “The capture of Tarawa knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific.”

Although a costly victory, Tarawa would prove to be beneficial. Soon, the Allied forces would isolate Rabaul and Truk so the invasion of the Marshall Islands, another step on the road to the capture of Japan itself, could take place.

In its editorial, TIME magazine had this to say to honor those who participated in the assault: “Last week some 5000 Marines, most of them now dead or wounded, gave the nation a name to stand beside those of Concord Bridge, the Bon Homme Richard, the Alamo, Little Big Horn, and Belleau Wood. The name was Tarawa.” n

Al Hemingway is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War. He is the author of Our War Was Different, published by Naval Institute Press, and writes often on military history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments