By Mike Phifer

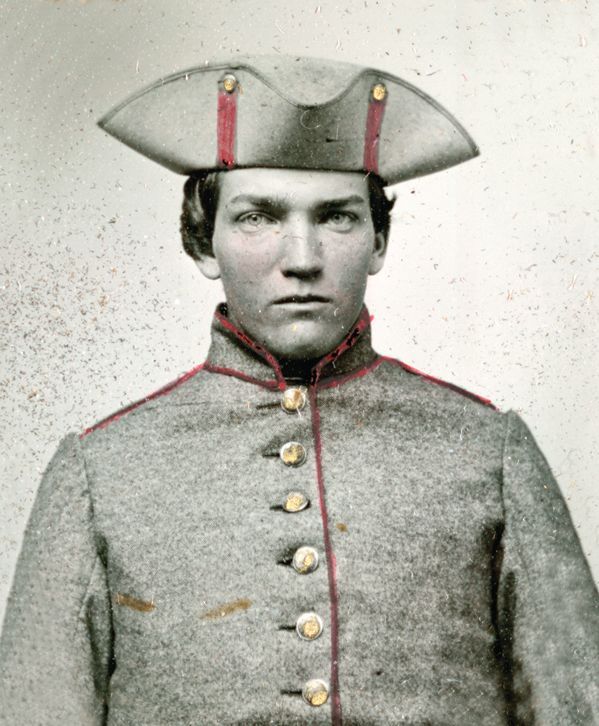

At midnight on November 13, 1863, two companies of the Palmetto (South Carolina) Sharpshooters Regiment led by Captain Alfred Foster slipped down to the south bank of the Tennessee River at Huff’s Ferry. Behind a river bend they were concealed from the Yankees positioned a few miles upstream on the north side opposite Loudon, Tennessee. Across the river, though, were enemy pickets. It fell to Foster’s men to capture them by surprise. The Rebels quietly shoved their boats into the cold water and climbed into them. Paddling across the river, Foster’s men secured the north shore but could find no enemy pickets. The rest of the sharpshooter regiment soon came across the river and secured a bridgehead.

While artillery was positioned to secure the south side of the crossing site, engineers toiled in the darkness stringing a pontoon bridge across the river. The task was made more difficult due to the strong current and insufficient anchorage, which bent the bridge. By dawn on November 14 the pontoon bridge was complete, and the Confederate troops marched across it.

The men belonged to Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s 15,000-man command whose objective was to drive the Yankees out of East Tennessee. The Federals would soon be aware of Longstreet’s presence because the pickets that Foster’s men had missed raced back with word that the Rebels were coming. A grueling campaign lay ahead for both sides as they battled not only each other but hunger and the weather in the third year of the war.

One of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s goals since the beginning of the American Civil War was the liberation of the mountainous region of Eastern Tennessee, which contained a large number of Union loyalists. From a military standpoint, the region was significant because it was a major railroad corridor for the Confederacy that linked Virginia and Tennessee. If the Union could sever the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad, which ran from Bristol, Virginia, to Knoxville, Tennessee, it would deny the Confederates the most direct railroad route between the two states.

Following his disastrous stint as commander of the Army of the Potomac during the Fredericksburg campaign, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was given command in March 1863 of the Department of the Ohio and the army of the same name. His initial orders were to invade East Tennessee to protect the left flank of Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland as it advanced toward Chattanooga.

Various events delayed Burnside’s advance. The first was Confederate Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan’s six-week cavalry raid that began on June 11 in which more than 2,000 Confederate cavalry rode through southern Indiana and Ohio. The second event was the detachment of the Union IX Corps to reinforce Union forces participating in the drive on Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Henry Halleck, the general in chief of the U.S. Army, knew all too well Burnside’s lack of aggressiveness and procrastinating nature, as exhibited by his tardy advance at Antietam in September 1862. Growing increasingly impatient with Burnside, Halleck ordered the commander of the Department of the Ohio to begin his march in early August against Knoxville, even though the IX Corps had not yet been returned to his command.

Halleck fired off a similar message to Rosecrans to resume his march on Chattanooga, which had ground to a halt in early July. Minus the IX Corps, Burnside’s Army of the Ohio comprised Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox’s XXIII Corps as well as cavalry and mounted infantry.

Burnside’s command marched south beginning on August 20 from different points in Kentucky. Within Cox’s 200-wagon supply train were 5,000 rifles that the Union army intended to distrib- ute to Union loyalists in East Tennessee. While the majority of Burnside’s troops headed for Knoxville, Burnside sent a detachment under Colonel John DeCourcy to secure Cumberland Gap.

Reduced to half rations, the bluecoats struggled along terrible roads. At various times, the Yankees had to manhandle their wagons and artillery up steep hills when their mules and horses had collapsed from exhaustion.

Burnside’s columns met little resistance from the enemy as they made their way into East Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Simon Buckner, who commanded the Confederate forces in that theater before Longstreet’s arrival, had received orders from Bragg to gather his 8,000 troops in the region and join Bragg’s army assembling along Chickamauga Creek in north Georgia. The first clash occurred at Loudon, Tennessee, when Burnside’s army bumped into Confederate cavalry. The Federals drove off the Rebel horsemen and then proceeded to burn the railroad bridge that spanned the Tennessee River. This bridge was part of the rail line that ran from southwestern Virginia through East Tennessee toward Georgia and Chattanooga.

Burnside reached Knoxville on the Holston River on September 3. (The Holston River joins the French Broad River at Knoxville to form the Tennessee River.) He promptly set up his head- quarters as the first step in securing East Tennessee for the Union.

To aid DeCourcy in taking Cumberland Gap, which was held by about 2,300 Confederate troops, Burnside dispatched a cavalry brigade to assist him. Confederate Brig. Gen. John W. Frazer, an ineffectual commander entrusted with holding the gap, was sufficiently intimidated by the Federals to surrender his entire force on September 9.

With only a small Confederate force under Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones on the Virginia-Tennessee border, Burnside assumed that he had fulfilled his objective of conquering East Tennessee. Plagued with intestinal trouble, Burnside asked Lincoln to be relieved of command. Lincoln informed him that his services were still required.

Burnside returned to Knoxville with orders from Halleck to vanquish Jones and link up with Rosecrans, even if the latter objective was only achieved with his cavalry. Burnside shifted his forces northeast to deal with the growing Confederate menace near the Virginia border.

Jones divided his command. He sent Brig. Gen. John Williams’ cavalry brigade, which was composed of the 1st Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry and 4th Kentucky Cavalry, south along the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad with orders to disrupt Union communications and capture Bull’s Gap. He also sent Maj. Gen. Robert Ransom’s brigade to retake Cumberland Gap.

Williams advanced no farther than Blue Springs, which lay midway between Bristol and Knoxville, while Ransom wound up withdrawing to Virginia. By that time, Brig. Gen. Robert B. Potter’s IX Corps had rejoined the Army of the Ohio. In addition, Burnside also received Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox’s division, an infantry brigade from the XXIII Corps, and some cavalry units.

On October 10 Burnside defeated Williams’ cavalry brigade at Blue Springs. The Rebels retreated toward Virginia. As for Burnside, he returned to Knoxville but left a strong detachment to keep an eye on this sector.

In reaction to Williams’ repulse, Bragg dispatched two cavalry brigades and Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson’s division, which was composed of three brigades, to threaten Burnside and secure the area south of Knoxville. The Confederates overwhelmed Colonel Frank Wolford’s Federal cavalry brigade in a brief clash on October 20 at Philadelphia, Tennessee. The Confederates, which sought to secure control of the key railroad stop on the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad, captured most of Wolford’s Kentucky cavalry. The Yankees who escaped withdrew six miles north to Loudoun. It was the first defeat of Union forces in the unfolding East Tennessee campaign. Burnside, who was concerned over the strong Rebel presence south of the Tennessee River, evacuated Loudon on October 28. He left a brigade from Brig. Gen. Julius White’s division on the north side of the river near the town. It was about this time that Burnside again reminded Lincoln of his diminishing health and desire to be relieved once the East Tennessee crisis was over. Again he was not allowed to leave his command.

On October 18 Washington gave Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant command of the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi. The key promotion gave Grant control of the Armies of the Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee. From that point on, Grant would control Burnside’s movements. Grant immediately urged Burnside to secure his position by stockpiling ammunition in case the Confederates managed to cut his supply line to Kentucky. It was sound advice. Burnside’s troops would need cartridges they could get their hands on as Longstreet’s Confederates would soon be headed their way.

Following the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg in July 1863, Longstreet was sent to the Western theater two months later. The arrival of his corps tipped the scales in favor of the Confederates at the Battle of Chickamauga, and it was one of Longstreet’s finest hours as he delivered a sledgehammer attack on September 20 that smashed Rosecrans’s army. The brilliant assault with his crack troops in forested terrain earned him a new nickname, “Bull of the Woods.”

But Longstreet, like other proud Confederate generals, clashed repeatedly with the irasci- ble commander of the Army of Tennessee. Following Chickamauga, Bragg’s army had become more dysfunctional than ever before. A dozen of his senior commanders, including Longstreet, signed a petition in early October asking Confederate President Jefferson Davis to remove Bragg from command of the army. The charges were severe enough to compel Davis to travel to the front to assess the situation in person. Despite the best efforts of Bragg’s detractors, the surly army commander remained. Like a cornered animal, he sought revenge against his critics using a number of methods, such as transfers and suspensions, to rid himself of them. Bragg informed Davis on October 31 that he planned to send Longstreet into East Tennessee to secure the area.

Bragg informed Longstreet of his plans on November 3. Longstreet, who had heard rumors of Bragg’s plan, argued that the Army of Tennessee should abandon Missionary Ridge and fall back behind Chickamauga Creek in north Georgia. Longstreet suggested that Bragg might send a large force of Confederates to strike Burnside. Once that objective was accomplished, the detached force could either return to north Georgia before the Federals could respond or it could push into Middle Tennessee and strike Grant’s supply bases.

Bragg dismissed Longstreet’s suggestions. On November 4 Bragg ordered Longstreet to advance into East Tennessee and either destroy Burnside or at the very least drive him out of the region. Bragg gave Longstreet 10,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 35 guns to carry out his objective.

Upon receiving his orders to drive Burnside out of East Tennessee, Longstreet prepared his troops to entrain to Sweetwater, which was located 40 miles south of Knoxville. From there they would march against Knoxville. Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ division began arriving at Sweet- water on November 6, but Maj. Gen. John Hood’s division, which was led by Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins following the life-threatening wound Hood received at Chickamauga, found themselves delayed due to the aging locomotives the Confederates were using. Colonel Porter Alexander’s artillerymen did not set out for Sweetwater by rail until November 10. The following day, the Confederates detrained at Sweetwater.

Longstreet was immediately confronted by a supply problem. Stevenson, who was marching back to rejoin Bragg’s army, informed Longstreet that he had no rations for him. Longstreet had no choice but to wait for a supply wagon train from Bragg. Although Longstreet received some wagons, he never received as many as his troops needed during the campaign.

At dawn on November 13, Longstreet began his advance from Sweetwater toward Loudon. In the meantime, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry was sent to seize the heights on the south side of the Holston River opposite Knoxville. By dawn on November 14 Longstreet’s men began moving across the pontoon bridge just completed across the Tennessee River at Huff’s Ferry.

White was informed that Federal pickets had spotted the Rebels crossing the river, and he passed the information to Burnside. By that time, Burnside had received a telegram from Grant informing him that the Federal army at Chattanooga would soon make an assault against Bragg in hope of forcing Longstreet to return; however, that attack was postponed. Grant also sent two officers to visit Burniside at his headquarters on November 13. The visitors were Colonel James Wilson of Grant’s staff and Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana. After a long meeting with the two men, Burnside resolved to engage Longstreet in order to lure him back to Knoxville. The goal of the attack would be to stretch the Confederate commander’s supply line and prevent him from returning to Chattanooga.

Leaving his chief engineer, Captain Orlando Poe, to look after Knoxville’s defenses, Burnside set out for Lenoir’s Station on November 14. Dana and Wilson accompanied Burnside. After arriving at Lenoir’s Station, Burnside ordered Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero to march his division to Huff’s Ferry, which was situated eight miles to the southwest. Ferrero was joined along the way by Colonel Marshal Chapin’s brigade. During their march, the Federals skirmished with Rebel forces near their bridgehead and secured a nearby bluff.

Federal forces withdrew the following morning toward Lenoir’s Station just as Longstreet began his advance. It was almost dark when Jenkins had troops in position southeast of Lenoir’s Station. McLaws’ division arrived soon afterward and bivouacked for the night a few miles to the rear. The Federals prepared to retreat out of Lenoir’s Station. Much of the artillery was sent off during the night on the muddy Lenoir Road. The Yankees spent a good part of the night destroying wagons and supplies they could not take with them. Just before sunrise on November 16, tired and cold Federals slogged out of Lenoir’s Station.

McLaws’ division advanced along Kingston Road toward Campbell’s Station in the hope of cutting off Burnside’s retreat, but the Federals beat the Confederates to the hamlet. The crossroads would become the scene of a sharp clash that day.

The 6th Indiana Cavalry and Colonel John Hartranft’s division of the Union IX Corps held the key junction. The Federal horse soldiers spurred their mounts west along Kingston Road to engage the Confederates. Hartranft’s division took up positions on both sides of the Kingston Road just west of the intersection to buy time for the main column of retreating Federals. In less than an hour the Indiana cavalry made contact with Rebel cavalry riding ahead of McLaws’ troops. Rebel infantry and artillery were soon brought up to help the cavalry drive back the Federals.

In the interim, fighting erupted along Little Turkey Creek about two miles away. Colonel William Humphrey’s brigade of Ferrero’s division faced Jenkins’ brigade of South Carolinians, commanded by Colonel John Bratton. Positioned on the west side of the creek, the outnumbered 17th Michigan put up a fierce holding action as long they could. With their flanks threatened, the bluecoats gave way and splashed across the creek.

The 17th Michigan formed up with the two other regiments of the brigade. With Bratton attempting to flank him, Humphrey’s ordered his men to fall back in echelon under fire. After driving back another attempt by Bratton to flank him, Humphrey took up position near the road junction where he was reinforced by Colonel David Morrison’s brigade. The crack of musket fire filled the air as the two sides made contact. By this time the Federal supply train was past the road intersection. Bratton’s brigade and Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson’s brigade moved against Humphrey and Morrison in an effort to flank them. Both Federal brigades skillfully withdrew at the double quick and joined Hartranft’s men, who were already falling back.

The bluecoats took up a new battle line at Turkey Creek near Campbell’s Station where Burnside had earlier ordered Union batteries to take up position on a bluff. The Federal guns, supported by some of their infantry, broke up an attack by Jenkins around noon. While Rebels guns traded fire with the Yankee batteries, McLaws arrived on the scene and formed his brigades into a battle line stretching to the north from Kingston Road. Longstreet ordered him to threaten Burnside’s right flank. McLaws believed that Jenkins would do the same on the Federal’s left flank. Poor communication led each division commander to believe the other was to launch the main assault.

At 3 PM Jenkins ordered Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s brigade of Alabamians, supported by Anderson’s brigade of Georgians, to flank the Federal left using the cover of trees and rough terrain. The Federals spotted the Rebel movement and withdrew to a new position on some high ground east of the creek. Longstreet pursued the Federals. Both sides deployed their artillery. The artillery batteries traded fire until darkness put an end to the Battle of Campbell’s Station.

After nightfall, the bluecoats resumed their retreat toward Knoxville. While Longstreet pushed toward Campbell’s Station, Wheeler’s horse soldiers secured Maryville on November 13. Wheeler then advanced to the high ground south of Knoxville, forcing back Brig. Gen. William Sanders’ Federal horse soldiers. Federal infantry, however, counterattacked and reclaimed the heights.

The Federals tramped into Knoxville on the morning of November 15. Poe told the Federal brigade commanders where to position their men on the city’s defensive perimeter. The newly arrived bluecoats soon were busy entrenching. They also set to work enlarging an existing Confederate strongpoint known as Fort Loudon. Everyone pitched in. Federal soldiers worked alongside Union loyalists and African Americans to improve Knoxville’s fortifications.

To buy time for the completion of the fortifications, Burnside ordered Sanders to deploy his mounted troops in an effort to slow Longstreet’s advance on the Kingston Road west of the city. Sanders’ screening force collided with the Rebels at mid-morning. The Confederates gradually pushed him back. Sanders’ troops made a stand in the late afternoon on a hill north of the road. To strengthen his hold on this key hill, Sanders had his men build breastworks using fence rails.

Burnside asked Sanders that night whether he could continue to hold his position so that the troops could have more time to finish the defensive works. Sanders assured Burnside that his troops would do everything within their power to keep the Rebels at bay.

Longstreet began deploying his troops around Knoxville on November 18. McLaws held the Confederate line from the Holston River north across the Kingston Road, and Jenkins extended the Rebel line to the Tazewell Road north of the city. At the same time, skirmishers from Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade probed Sanders’ position.

The 8th Michigan Cavalry held Sander’s left flank, the 112th Illinois Mounted Infantry was in the center, and the 45th Ohio Cavalry was on his right. These dismounted horse soldiers held their position until mid-afternoon, which was several hours longer than Sanders had promised Burnside.

The fighting heated up when a section of Confederate artillery began shelling the Yankee breastworks, which sent fence rails flying through the air. The 2nd and 3rd South Carolina Regiments charged and carried the Federal position. Sanders was among the Federal casualties. He died the following day.

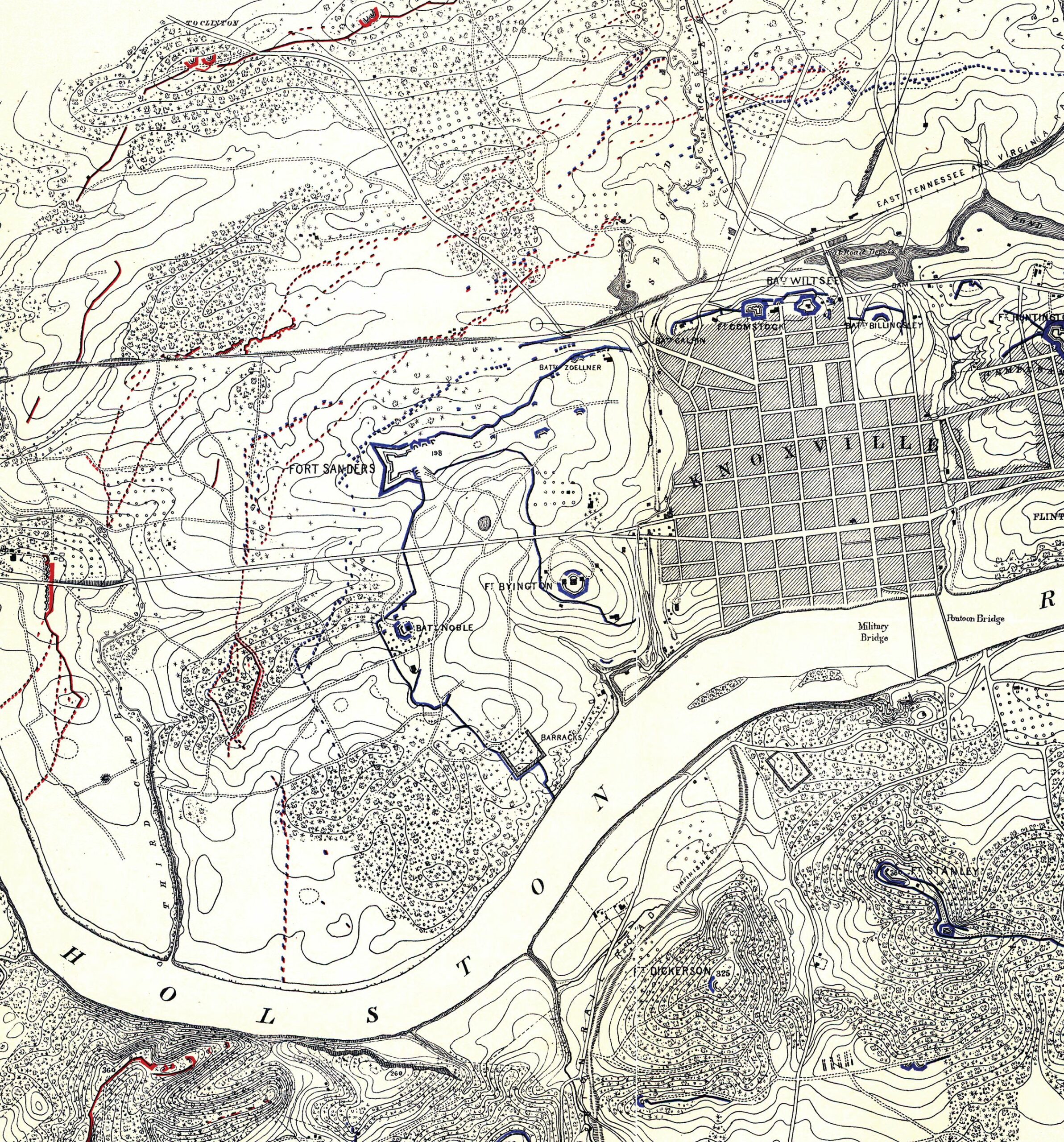

Under Poe’s watchful eye, the Federals constructed their defenses to the west, east, and north of the town. Burnside’s Federals were covered to the south by the Holston River. When the work was completed, the Federal defenses included 13 strongpoints around the city. The Federals gave Fort Loudon, which anchored the northwest corner of the city’s defenses, a new name. In honor of the fallen cavalry commander, they renamed it Fort Sanders.

The enlarged fort, which was 95 yards long on the west side and 120 yards long on the north and south sides, consisted of two bastions. The side that faced the interior of the Federal lines was left open. The outside perimeter of the fort was protected by a wide ditch. Atop the tall parapets, the Yankees had placed cotton bales with green hides draped over them to prevent them from catching fire from cannon and musket fire.

The northwest bastion of Fort Sanders was a prominent salient in the main line and thought to be the most vulnerable spot in the Union defenses. To strengthen it, the Federals strung telegraph wire between tree stumps. They also constructed abatis—branches of trees laid in a row with their sharpened points directed outward toward the attacking force.

Poe had ordered those working on the defenses to dam parts of First Creek and Second Creek to create water obstacles to thwart the attackers. The soldiers and civilians working on the fort also prepared secondary positions inside the fort to which the soldiers could withdraw if the perimeter was breached. The Federals also fortified the hills on the south bank of the Holston River opposite the city to deny that key terrain to the Confederates. To protect the vital pontoon bridge that stretched across the river, Poe ordered the troops to build two booms that were placed across the river to prevent the Confederates from floating debris downstream in an effort to destroy the bridge.

The Confederates also were busy fortifying their positions. Using mostly captured shovels and picks taken at Lenoir’s Station, Longstreet’s troops dug earthworks and batteries on the west and north side of the Federal lines. On November 19 Wheeler’s cavalry deployed in a line opposite the Federal works east of the Tazewell Road. Because they had so much ground to cover, the dismounted troopers were spread thin.

Following the arrival in East Tennessee of the Federal IX Corps, Burnside had approximately 30,000 troops in the region. But when Longstreet arrived at Knoxville, the Union commander had only 12,000 defending the city. Although Longstreet’s troops besieged his army on three sides, Burnside was not cut off because the area south of the river was open to him. He regularly sent out foraging parties to gather whatever they could find to help feed his troops. Union loyalists also sent food downriver to the city to supplement the Federal supplies. Nevertheless, Burnside was forced to put his men on half rations and sometimes even on quarter rations.

The Confederates were in even worse shape than the Federals regarding rations and supplies. The railway that carried their supplies ended at Loudon where the bridge was down. From that point, wagon teams had to haul their supplies over muddy roads to Knoxville.

Federal skirmishers posted in rifle pits outside their main works delivered a steady and accurate fire at the Rebels. The Yankees occasionally launched sorties in an effort to push back the Confederates. A Federal sortie on November 24 resulted in 83 casualties when the Yankees tried to drive away Rebel sharpshooters. The Federals captured an enemy trench, but they were driven back to their lines by a determined Rebel counterattack.

The same day, most of Wheeler’s command arrived outside Kingston, located southwest of Knoxville.

Concerned over the Yankee presence, which threatened his supply line, Longstreet ordered Wheeler to leave behind a brigade to hold its position at Knoxville and take the majority of his command south in an attempt to capture Kingston. A Yankee brigade and regiment of mounted infantry held Kingston. After some desultory skirmishing, Wheeler decided that the Federal position was too strong to carry, so he decided not to attack. The disgruntled Confederate cavalry returned to Knoxville. When he got back to Knoxville, Wheeler received orders to rejoin Bragg to take command of Bragg’s cavalry. Command of Wheeler’s cavalry at Knoxville devolved to Maj. Gen. William Martin.

Longstreet pondered the best way to capture Knoxville. He suggested that McLaws attack Fort Sanders with his three brigades under cover of night on November 22. After discussing the matters with his subordinates, McLaws informed his superior that his brigade commanders could not effectively direct the advance of their men in a night operation. Based on that reasoning, Longstreet cancelled the night attack.

After reconnoitering the south side of the river where the 10th Georgia had recently captured bluffs opposite McLaws’ line, a Confederate staff officer suggested a battery could be positioned at that location to shell Fort Sanders. This would allow the Rebels to bombard the fort from three directions. Longstreet agreed. Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s artillery chief, ordered Captain William Parker’s Virginia battery to cross the river on a makeshift ferry. Two Confederate brigades, Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s brigade and Brig. Gen. Jerome Robertson’s brigade, were to support the battery. Working through the night of November 24-25, the Confederates cut a road up the steep bluff, and then hauled the guns into position for a major assault scheduled for the following day. But Longstreet postponed the attack when he learned that Bragg was sending reinforcements under Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson. He planned to wait for Johnson’s troops before launching the attack.

On November 25, elements of Law’s and Robertson’s brigades fought a brisk engagement with Colonel Daniel Cameron’s brigade at Armstrong Hill. The Federals repulsed the Rebel attack. The bluecoats then began to extend their works south of the river.

That night Brig. Gen. Danville Leadbetter, who was the chief engineer of the Army of Tennessee, arrived and the next day conducted a reconnaissance of the Yankee works with Longstreet. Leadbetter favored an attack from the Confederate left against Mabry’s Hill, which anchored the northeast corner of the Federal lines. Much to Alexander’s chagrin, Longstreet agreed with the engineer and ordered him to move most of Parker’s battery back across the river to support the attack scheduled for November 28.

A second reconnaissance on November 27 by Longstreet and other high-ranking officers revealed the futility in attacking Mabry’s Hill. Attackers would have to cross a fair piece of open ground while under fire and be seriously hampered by a creek and ponds in their way. By that time, Johnson had arrived with two fresh brigades totaling 2,600 men.

After returning from his reconnaissance of the Federal defenses, Longstreet decided that he would send his troops against the northwest bastion on the morning of November 28. McLaws was tasked with leading the assault.

Brutally cold weather set in. McLaws requested that the attack be delayed until November 29. On the evening of November 28, Longstreet heard rumors circulating throughout his army that the Federals had driven Bragg from Missionary Ridge.

McLaws took that opportunity to suggest that Longstreet postpone the attack indefinitely until the rumors could be confirmed. Longstreet vehemently disagreed. “There is neither safety nor honor in any other course than the one I have chosen and ordered,” said Longstreet. Come what may, the Confederates would attack the following morning at daybreak.

The deep ditch surrounding the bastion greatly concerned Jenkins. After failing to find Longstreet, Jenkins told McLaws that the first troops to reach the ditch should fill it with fascines so that those following them could cross the ditch more easily. McLaws dismissed his concerns. If the ditch was deep, he said, the troops would just have to trust their luck that they would be able to get over or around it.

Jenkins then approached Alexander with a proposal that the infantry build ladders to bridge the ditch. Alexander thought it was a good idea. They approached Longstreet, but he did not believe it was necessary. If the men showed enough determination, they would make it across the ditch, he said.

Around 10 PM on November 28 Confederate skirmishers advanced with orders to drive back the Federal skirmishers outside the fort. The graybacks overran the Yankee pickets. This would enable the Rebel skirmishers to furnish covering fire for the planned massed infantry attack.

On the morning of November 29, McLaws’ troops prepared to attack in two columns. The left column consisted of Brig. Gen. William Wofford’s brigade, which was commanded by Colonel Solon Ruff since Wofford had fallen ill. The right column was made up of regiments from Brig. Gen. Benjamin Humphreys’ and Brig. Gen. Goode Bryan’s brigades. Johnson’s two brigades formed the reserve. Anderson’s brigade of Jenkins’ division was to attack the Federal line east of Fort Sanders, while two of Jenkins’ brigades served as a reserve. This force numbered approximately 6,000 men.

Lieutenant Samuel Benjamin commanded four 20-pounder Parrots from his Company E of the 2nd U.S. Artillery, six 12-pounder Napoleons from the Rhode Island Light Artillery, and two 3-inch Ordnance Rifles from the 2nd New York Light Artillery. The supporting garrison, which was drawn from IX Corps, consisted of approximately 400 troops from four regiments.

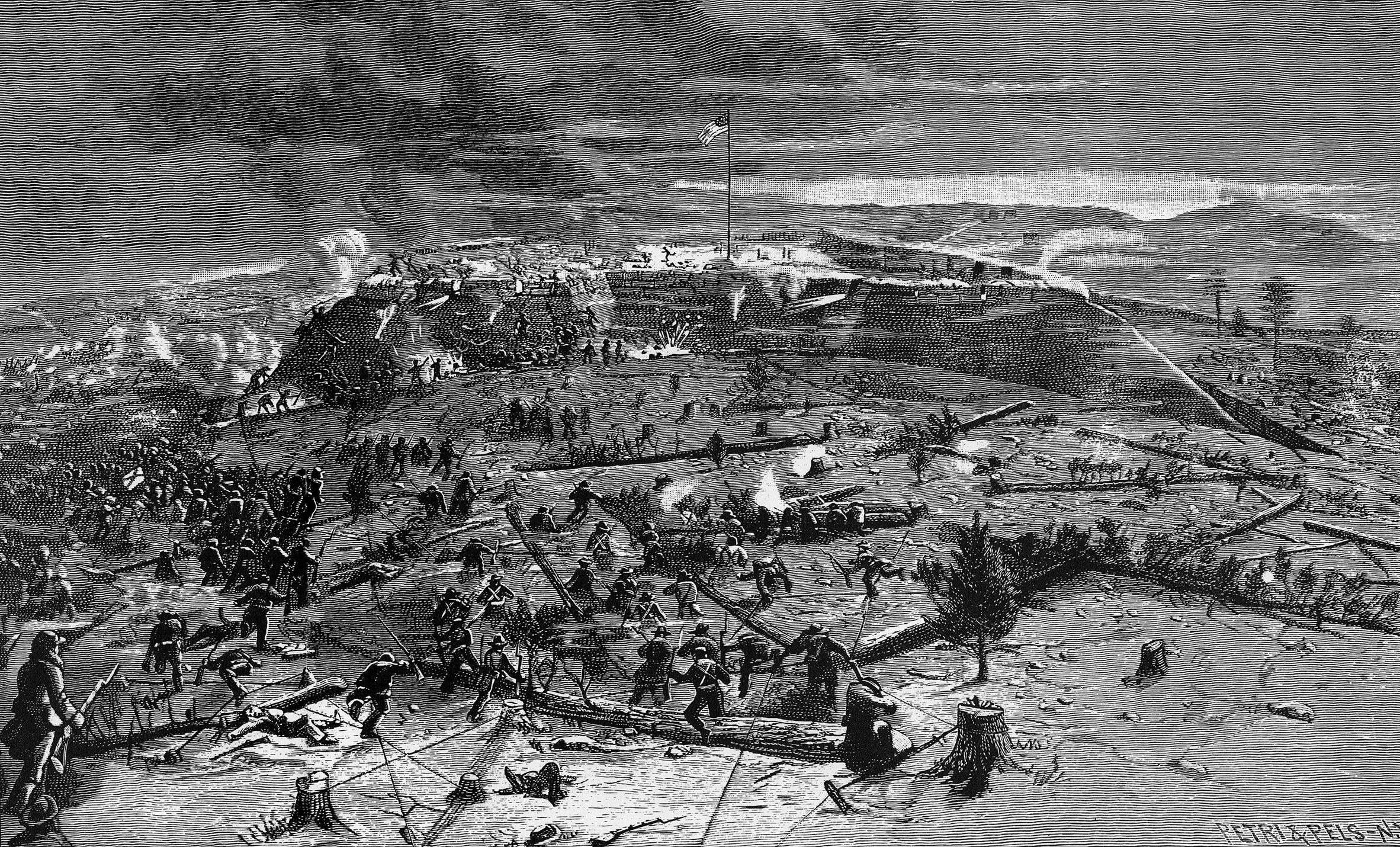

At dawn the Rebel guns opened up, signaling that the attack was about to begin. More Confederate guns soon began shelling Federal strongpoints around Knoxville, including Fort Sanders. After about 20 minutes the guns mostly fell silent. Then, McLaws’ infantry began advancing toward Fort Sanders.

At Fort Sanders, Benjamin had only one gun that he could bring to bear on the Rebel columns. He loaded it with triple canister, but the gunners did not have time to get off many rounds. As they narrowed the distance to the forward lines, the attacking Confederates began falling over the telegraph wire. The Federals poured musket fire into their ranks as the hapless Confederates negotiated the obstacles.

Pushing past the telegraph wire and through the abatis, the two Rebels columns were clos- ing in on the northwest bastion when they encountered the deep ditch. The advance briefly stopped as troops began to crowd in front of the ditch. With no choice but to go forward, the Rebels jumped into the ditch. Men struggled to claw and scratch their way up the slippery far side of the ditch and the looming parapet, with most sliding back down again. A handful climbed up on their comrades’ shoulders only to be shot down when they reached the top of the parapet. Others tried to crawl through the narrow gun embrasures but were killed by musket or canister rounds.

As the Rebels struggled to get into the fort, they managed to briefly plant three flags on the parapets. The bluecoats redoubled their efforts to repulse the attackers. Private Joseph Manning of the 29th Massachusetts Infantry remembered being “in a fever of excitement” loading and firing as fast as he could. Picking up artillery shells and cutting their fuses to five seconds, Benjamin lit them and tossed them down into the mass of Rebels struggling in the ditches.

Confederate casualties were quickly mounting not only from the defenders of Fort Sanders, but also from flanking fire from the Federal lines to the east. With no chance of taking the bastion, many Rebels began to fall back. This proved as dangerous as they had to endure fire as they withdrew across open ground. Others remained in the ditch. The attack was over in 20 minutes.

“I saw some of the men straggling back, and heard that the men could not pass the ditch for the want of ladders or other means,” wrote Longstreet. “Almost at the same moment I saw that the men were beginning to retire in considerable numbers, and very soon the column broke up entirely and fell back in confusion.” Longstreet called off the attack.

Rebels approximately 800 men, one quarter of which were taken prisoner. In contrast, the Federals suffered approximately 100 casualties. Not long after the repulse Longstreet received word that Bragg had been severely defeated at Chattanooga. Davis advised Longstreet to wrap up the siege and rejoin Bragg. Shortly afterward, Longstreet gave the order to retreat. He countermanded the order, though, when he learned that Bragg had retreated to Dalton, Georgia. Bragg offered him the choice of joining him at Dalton or returning to Virginia. Longstreet chose neither option. After consulting with his division com- manders, the Bull of the Woods decided to continue the siege in an effort to tie up Federal forces that might be used against Bragg.

Under pressure from Washington to rescue Burnside, Grant dispatched Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to relieve Knoxville. But Longstreet eventually decided to return to Virginia. On the night of December 4-5, he ordered his men to break camp but leave their campfires still burning to deceive the Federals in Knoxville. In a cold rain, Longstreet’s battered command marched away from Knoxville. The siege of Knoxville was over. In total, the Knoxville campaign had cost the Confederates 1,300 casualties, and the Federals approximately 700 casualties.

After a gruelling march through rough terrain, Sherman arrived at Knoxville on December 6. Given the supply challenges that Burnside faced, he was surprised that his men were not on the verge of starvation. Except for Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger’s corps, Sherman’s command countermarched to Chattanooga.

With Granger’s men holding Knoxville, Burnside sent his cavalry after Longstreet on December 5 and then sent the IX and XXIII Corps to join the pursuit two days later. Perhaps the Federals believed that Longstreet’s men were whipped, but they would learn otherwise.

On December 14 Longstreet defeated the Federal cavalry under Brig. Gen. James Shackelford at Bean’s Station. The Confederates pursued the retreating Federal horse soldiers. On December 16 the Confederates found them in a strong defensive position at Blain’s Cross Roads about 15 miles northeast of Knoxville. At that point, Longstreet resumed his retreat east. His command bivouacked for the winter in East Tennessee before returning to Virginia.

Burnside left Knoxville on December 12 after he was relieved of command. In late January 1864, Burnside and his men received a resolution from the U.S. Congress thanking them for their efforts at Knoxville. Like many of the bluecoats marching east, Captain Henry Burrage of the 36th Massachusetts took pride in the IX Corps’ role at Fort Sanders, remembering it “was Fredericksburg reversed.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments