By Barry Porter

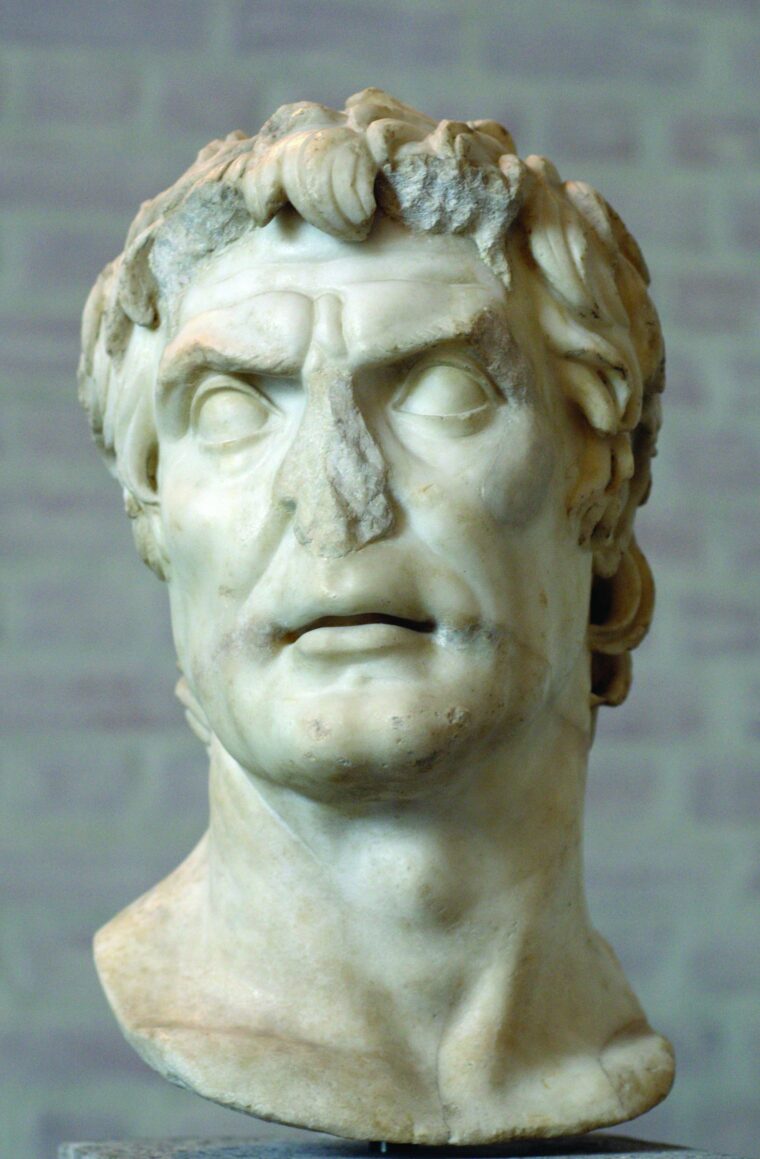

By the winter of 82 bc, the Roman civil war had been raging off and on for six years. The aristocrats of society, known as the Optimates, were pitted against the Populares, or common men, who were demanding more rights and power for their growing numbers. Under the brilliant but brutal leadership of General Lucius Cornelius Sulla, an Optimate, the question of who would control Rome soon would be decided. Sulla had enjoyed the upper hand for months, but now he had been forced to divide his forces and race for Rome, desperately hoping to head off an army that was larger than his own. Sulla’s haste looked like the beginning of the end for him and his cause.

General Gaius Marius’ Private Proletariat Army

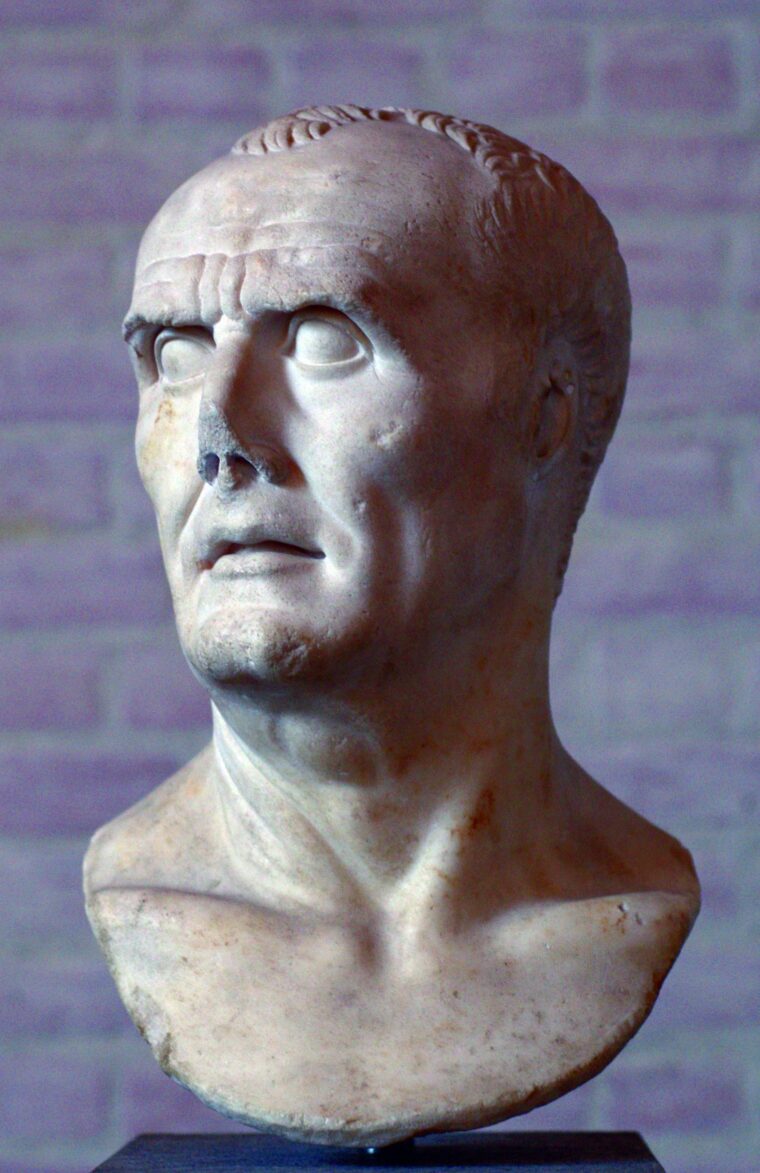

Sulla’s hurried gambit had its roots in the personal rivalry between him and his former commander and friend, General Gaius Marius. Marius was a so-called new man, a plebeian who had worked his way up the political ranks through hard labor and sharp ingenuity rather than through the family connections that took many aristocrats to the top. He spent a busy career building a power base for common men without lands or titles. In 107 bc, he bucked tradition and acceptable behavior by running for consul, the top spot in the Roman political hierarchy, against the son of an aristocrat and former consul, Quintus Metellus. Marius shocked the Optimates by winning. He further angered them by removing Metellus as general in a campaign against the Numidian ruler Jugurtha in northern Africa and placing himself in command of the Roman armies there. He poured more salt into the Optimates’ wounds by doing away with the minimal requirements necessary for a man to become a soldier. In this way, Marius managed to build a large proletariat army that owed its standing—and loyalty—to Marius personally, not to Rome.

Marius’s dream of capturing Jugurtha and using the triumph to blunt the anger of the Optimates was sorely disappointed. Instead of bagging the rebellious Numidian himself, Marius saw one of his junior lieutenants, the Optimate officer Lucius Sulla, capture Jugurtha through trickery. And though Marius ultimately received credit for ending the war, all of Rome knew who had truly brought the wily enemy to his knees—an aristocrat who was now the newfound favorite of other aristocrats.

Sulla continued his successful rise under a new commander in Germany, battling and besting the barbarians who had invaded southern France and northern Italy. As for Marius, he also proved victorious against the Germans and in the equally important struggle for the hearts and minds of the Roman people. Although Roman law prevented a man from holding the consulship for two years in succession, by 100 bc, Marius had garnered an unprecedented six consulships.

Marius in Exile

That same year, Marius’s—and Rome’s—problems really began. A tribune of the plebeians, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, sponsored a bill in the Senate that provided for land to be allotted to Latins and Italians who had been soldiers in the African campaign, along with full Roman citizenship for many of them. Unfortunately, some of his fellow plebeians objected to the bill (which might have cut into their own power) and threw the tribune’s comitia into chaos. As elections drew near, Saturninus became so concerned that his colleague Marius was going to lose the consulship that he hired a group of thugs to attack the rival candidate. Full-blown riots broke out. At the direction of the Senate, Marius led armed soldiers into the forum and forced his own political allies to surrender. Since they were fellow Populares, Marius tried to protect Saturninus and his associates by placing them in the Senate quarters for safekeeping. He did not foresee that an angry mob would quickly storm the building and kill everyone inside. There was nothing he could do to stop it.

The deaths stained Marius’s reputation with both the Populares and the Optimates. As Optimate senators gleefully struck down Saturninus’s legislation, Marius had to deal with angry plebeians who blamed him for his allies’ murders. Marius found it prudent to get out of Rome for a few years. He hurried to Pontus, in Asia Minor, where he hammered out a deal with a potential enemy of Rome, Mithridates VI. He took a hard line with the Pontus leader, forcing Mithridates to agree not to invade neighboring lands, and he was rewarded with a rise in his reputation and a safe return to Rome in 96 bc. For the time being, at least, he had been rehabilitated.

A Contest of Victories in the Social War

Sulla, meanwhile, had also risen in reputation during Marius’s years in exile, and it did not sit well with the Populare leader. The rivalry between the two men came to a head when Sulla was accused of extortion by a politically motivated friend of Marius at the same time that Marius was publicly leading efforts to tear down a new statue that depicted Sulla accepting Jugurtha’s surrender. Civil war might have broken out then and there, but a new conflict suddenly intruded: the Social War between the Romans and the indigenous Italians, who were sick of being treated as second-class citizens in their own country.

Marius once again proved himself a capable general by turning back the tide of Italians at Fucine Lake and Asculum after several other generals had failed to do so. However, he was still widely disliked by the Optimates in the Senate, and he never received any official promotion for his most recent victories. To make matters worse, Sulla proved just as successful in the Social War, capturing the rebel stronghold at Pompeii, and was voted in as consul in 88 BC and given a command against an enemy that Marius thought he had tamed already—Mithridates VI, who was busy rampaging through Asia Minor and killing any Romans who stood in his way.

Gaius Marius: Enemy of the State

With the Social War won (although the Romans won militarily, the war ended ironically with the passing of the Lex Julia, which gave the Italians the enfranchisement they had been fighting for all along), Sulla prepared to leave Rome. A political partisan of Marius’s introduced a series of new bills in the tribune’s comitia that renewed the rivalry between the two classes and their champions. The tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus proposed legislation that would distribute the newly enfranchised Italians evenly among the 35 voting tribes in the tribune’s comitia, thus favoring the Populares at the expense of the Optimates. He also proposed that all senators who owed a minimum amount of money be removed from office and that the field command against Mithridates be transferred from Sulla to Marius. This last suggestion of course enraged Sulla, and he tried to check the advance of the bill through the comitia. Sulpicius fought back and tensions quickly escalated until riots began again and Sulla found himself running for his life.

Sulla met up with his army, which was busy preparing to march to Asia Minor, and convinced them to march with him back to Rome instead. Now it was Marius’s and Sulpicius’s turn to run for their lives. Sulla captured Rome within the space of a few hours and had no difficulty in having Marius and his associates declared public enemies of the state. Sulpicius was hunted down and killed, but Marius managed to escape to North Africa, where many veterans from his previous African campaign still lived. Meanwhile, Sulla dismantled Sulpicius’s legacy by making all of his bills null and void. Sulla then went to work undermining the power of the plebeians. First, he forced the newly enfranchised Italians to be distributed among eight tribes rather than the entire 35. Then he decreed that only matters receiving the prior approval of the Senate could be brought before the comitia, and that such business would not be brought before the tribune’s comitia but before the comitia centuriata, which was comprised of both plebeians and aristocrats and usually favored the Optimates. Since tribunes, who tended to be Populares, were prevented by law from presenting bills before the comitia centuriata, their power to influence Roman policy was severely blunted.

Sulla prepared to take his army to Asia Minor to deal with Mithridates. Before he left, he made one of the newly elected consuls, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, a Populare (and the father-in-law of a rising young tribune named Gaius Julius Caesar), promise that he would not meddle with the changes Sulla had made while he was away. Cinna agreed—at least long enough to get Sulla out of Rome. Once Sulla was gone, however, Cinna reintroduced Sulpicius’s legislation to distribute the new Italian citizens among the 35 tribes of the tribune’s comitia. Once more, turmoil rolled through the Forum. In short order, Cinna was declared a public enemy and his fellow consul, Gnaeus Octavius, restored the distribution of new Italian citizens to the way Sulla wanted it.

Bloodbath in Rome

But Cinna’s removal from Rome did not end the political turmoil. Cinna, like Sulla, raised an army within Latium and Campania, where he found support among plebeians and Italians. At the same time, Marius landed in Italy with his North African army and conquered Ostia, Rome’s port. The two men joined forces and together marched on Rome.

This time there was a bloodbath. Marius, driven by spite at his ill treatment, cut off the head of the rival consul Octavius and exhibited it in the Forum alongside the heads of other Optimates killed by his order. For five days the slaughter continued, until Cinna became so sickened by the excesses that he turned his own men against Marius’s murderers. Apparently Marius had slaked his thirst for physical vengeance, at least for the time being, and he joined with Cinna to institute their political revenge, exiling Sulla, repealing his laws, and officially restoring Marius as the commander of the eastern armies against Mithridates. They then manufactured their election as joint consuls in the year 86 bc. This was Marius’s seventh consulship, but he did not have long to enjoy it. Within days he fell ill and died.

Mutiny Among Cinna’s Ranks

As the remaining consul, Cinna took sole control of the city. With the government now under his thumb, he spent the next three years restoring order and ensuring peace within the walls of Rome. He cancelled three-fourths of all outstanding debts, which favored his fellow plebeians, and instituted regulations over future loans of money. He also distributed the new Italian citizens among the 35 tribes of the tribune’s comitia, which he hoped would bring an end to that lingering fight. The Senate cooperated with him, not because they favored Cinna’s legislation, but because they really had no choice if they wanted to maintain the peace—and keep their heads.

Despite progress on the home front, everyone in Italy was well aware that Sulla still commanded an army and that he was not at all happy with the sudden reversal of his fortunes. Cinna, more than anyone, understood the danger that awaited him beyond the walls of the Eternal City; while the Senate attempted to negotiate with Sulla, Cinna prepared for war. In 84 bc, he left his co-consul, Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, in charge of Rome and shipped out with his troops to cross the sea to Illyria to put down a simmering revolt.

Cinna also wanted to give his army some much-needed experience by fighting the Illyrians in preparation for the larger battle he envisioned with Sulla, who was camped uncomfortably nearby in Greece. It was a good idea—the more experience Cinna’s soldiers gained, the better able they would be to meet the challenge of defeating Sulla’s veterans. Cinna, however, did not count on bad weather and nervous troops. As his army crossed the Adriatic, some of the unstable transports encountered rough waves and sank. Their heavily armored passengers drowned within sight of land. The loss was devastating to the troops’ morale, but Cinna insisted that they continue onward. The soldiers resisted, and in the end they mutinied, stoning Cinna to death and bringing his campaign against Sulla to an abrupt end.

Disaster for the Populares

Back in Rome, word reached Carbo of Cinna’s disaster. Unfortunately for the Populares, Carbo did not command the same degree of loyalty that Marius and Cinna had enjoyed, nor did he possess their flair for generalship. In fact, he was widely considered outright incompetent, and he was not reelected consul the following year. As the year 83 bc dawned, Sulla landed at Brundisium in southern Italy with 40,000 troops, while two new, inexperienced consuls with equally inexperienced armies at their command marched south to meet him.

Sulla’s arrival in Italy inspired other exiled Optimates to join him. A bitter enemy of Marius, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, governor of Africa, led his forces into Italy to stand by Sulla. Other experienced generals, including Gnaeus Pompeius, nicknamed Pompey, arrived with three legions. Meanwhile, Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the richest men in Rome, also added his experience, wealth, and army from Spain to Sulla’s cause. Sulla’s ranks swelled to 50,000 men, soldiers who were loyal only to him, battle-seasoned veterans from the campaign against Mithridates who were willing to fight to the last man for control of Rome. (Crassus, who a decade later would put down the slave revolt led by rebel leader Spartacus, had accumulated much of his fortune by buying up burning buildings and having his 500-man private fire department put out the flames before his new property was destroyed.)

Sulla’s force made it as far as Campania in central Italy without opposition. Once they met the opposing forces, they were scarcely challenged. The army led by one consul, Gaius Norbanus, was defeated badly at Mount Tifata, near Capua, and the other consul, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiagenus, led an army so frightened by the ferocity of Sulla’s soldiers and their own unproven abilities that they abruptly changed sides. Asiagenus, suddenly finding himself without any men to command, surrendered without a fight. Sulla allowed him to return to Rome, perhaps to communicate terms to the Senate for Rome’s surrender, but Asiagenus immediately began to build a new army for a new campaign. Unfortunately for him, his new soldiers were just as raw as his previous troops, and when they met Sulla’s forces on the battlefield they, too, abandoned Asiagenus to stand behind Sulla.

Challenging the Siege

The year came to a close, and a bitter winter interrupted the fighting, while widespread panic gripped the citizens of Rome. The elections of 82 bc reflected the politicians’ desperation. Carbo was elected as consul for the third time and Gaius Marius the Younger, the 26-year-old son of Sulla’s old rival, became co-consul. Together they recruited troops from the Samnites in southern Italy, who had fought an unsuccessful war of their own against Sulla in the previous decade, and among the veterans who had fought loyally for Marius the Elder at the height of his popularity. As their forces began to grow and improve in quality, the Populare leaders turned their brutal attention to Rome’s government. Many of the senators who had recently come out in support of Sulla were slaughtered in the streets. It was manifestly unsafe to take sides—one way or the other—in the political turmoil.

When winter passed, the fighting in Italy began anew. Carbo took his forces north to confront Pompey’s legions, while Marius went south to stop Sulla’s advance. Carbo’s troops were no match for Pompey’s veterans. Carbo was quickly defeated and forced to retreat to Etruria, while Pompey’s and Metellus’s African soldiers secured northern Italy for Sulla.

Marius the Younger did not have any better luck in holding Rome with his Samnite forces. When he met Sulla’s army at Sacriportus a long, vicious battle ensued. If Marius had hoped his soldiers, many of them loyal to his dead father, would not switch sides to his father’s bitter enemy, he was sorely mistaken. Most of his troops did desert him, and Marius and his few remaining allies were forced to retreat to the walled town of Praeneste, 23 miles southeast of Rome. Sulla followed and laid siege to the town. As the attack continued, Sulla left his trusted lieutenant Ofella Lucretius in charge while he took the bulk of his army and hurried on to Rome.

Assembling at the Colline Gate

When Sulla entered the Eternal City, he discovered to his fury that many of his friends and supporters had been butchered by the urban praetor Lucius Junius Brutus Damasippus, upon the orders of Marius the Younger. Even senior senators had not been spared the sword. The massacre strengthened Sulla’s resolve; he immediately marched his soldiers out of Rome again and hurried north to confront Carbo at Etruria.

Carbo put up a heroic fight, but with no relief in sight, he suddenly lost his nerve and fled through the front lines to Libya. With Carbo gone and Marius the Younger under siege, the veteran soldiers of the elder Marius either surrendered to Sulla’s forces or ran for safety. The Samnites and Lucanians, however, proud Italians who long had fought for citizenship against the Optimates, picked up a few of those veterans and marched together in a combined force of 70,000 toward Praeneste, determined to rescue Marius the Younger from the ongoing siege. Sulla quickly brought his legions into battle to join his allies already besieging the city. Samnite leader Pontius Telesinus issued orders for his men to slam into the Sullan legions. Telesinus’s army outnumbered Sulla’s by several thousand, but despite their desperate efforts, they could not break through the enemy’s lines. Sulla’s men struck back hard, but they, too, found that they could not break the other side.

Confronted with a series of indecisive battles and hearing that Pompey’s forces were advancing against his rear, Telesinus decided upon a new strategy to draw Sulla’s armies away from Praeneste. By night, his Samnite and Lucanian forces made a surprise dash for Rome, which Sulla in his haste had left undefended. Sulla, realizing immediately what was happening, divided his forces, sending his cavalry ahead to hinder the enemy while he led his army forward at all possible speed.

As night fell, Telesinus camped a little more than a mile away from the Servian Wall at Rome’s northeast entrance, the Colline Gate. When dawn came, several thousand men from within the city, either supporters of Sulla or loyal patriots who could not stand by and see Rome invaded by non-Roman Italians, rode out and attacked Telesinus’s army. They were soon overwhelmed, and the cries of panicked men and women echoed through the city streets as everyone prepared for a massive invasion. At the nadir of Roman hopes, Lucius Cornelius Balbus, in charge of Sulla’s 700 horsemen, arrived outside the wall. Once his horses were refreshed, he led his cavalry in an attack on the Italians.

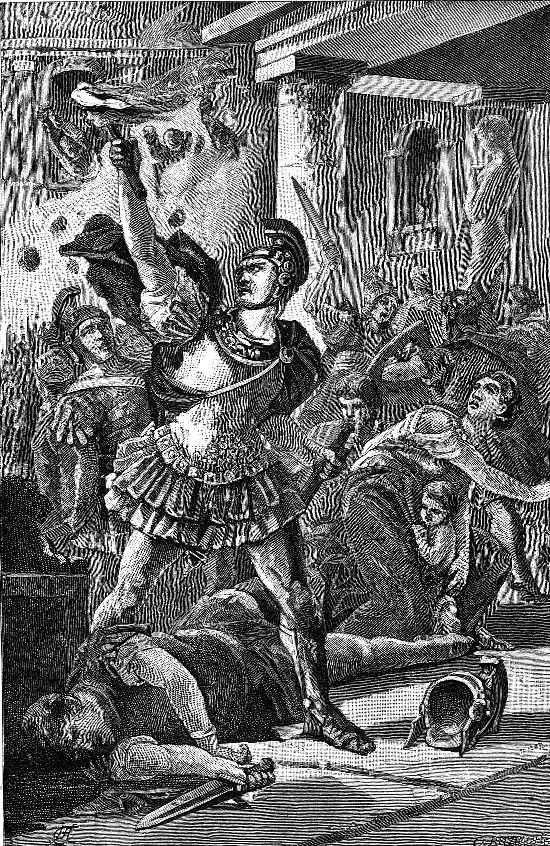

While his horsemen harassed the enemy, Sulla arrived on the scene, making camp outside the Colline Gate at noon. He allowed his men to eat a quick meal, then formed them into battle lines. By late afternoon, they were ready. At least two of Sulla’s lieutenants implored him to let his men rest after their fight at Praeneste and their long march to Rome, but Sulla was adamant. In the enemy camp, Telesinus also readied his men for battle, going from rank to rank and proclaiming boldly that the “final day is at hand for the Romans.” Then, amid the clamor of soldiers unsheathing their weapons and the thunder of horses bearing down on the city, Sulla’s trumpeters sounded the charge.

The Battle of Colline Gate

The clash was ferocious. Sulla led the left wing while Crassus controlled the right. As the battle progressed, the left wing began to fold. Sulla rode up on his white horse to rally his troops. He was immediately recognized by the enemy, who showered him with spears. Sulla did not see the attack coming, but his groom managed to lash Sulla’s horse, sending the animal bursting forward. The spears grazed the horse’s tail and landed harmlessly in the earth. Sulla, realizing his close call, kept on the move, entreating his warriors to do whatever they could to keep his lines strong. It was too late. His left wing broke under the enemy onslaught. Many of Sulla’s men ran for the Roman walls and the gate, seeking protection behind the barrier, but the old men guarding the gate dropped the portcullis on the bolters’ backs, killing several unwary senators as well as soldiers. The fighting continued on into the night, and Sulla was forced to retreat to his camp.

Sulla and many of his supporters feared that all was lost. Refugees from the fighting fled back to Praeneste and tried to convince the lieutenant in charge there, Ofella Lucretius, to end his siege and retreat to safety. For long hours, many Romans—including Sulla—thought the city had fallen to the Samnites and Lucanians. But gradually messengers showed up at Sulla’s camp asking for food and describing what had happened during the long night of fighting. Although Sulla’s left wing had collapsed, the right wing under Crassus had held firm. Telesinus had been killed in the battle, and his Roman allies had fled. Crassus’s troops killed the majority of the enemy until the Italians fell back and fled to the city of Antemnae. Crassus followed and now was encamped outside the city, awaiting Sulla’s arrival.

Sulla, understandably ecstatic, led his troops to Antemnae. There, through negotiation with the inhabitants of the city, 6,000 enemy troops were taken into custody. They were all that was left of the great army led by Telesinus. By the next day, many of the Roman generals who had fought beside Telesinus were rounded up and beheaded. Sulla ordered their heads placed on pikes alongside that of the unfortunate Telesinus and sent to Praeneste, where they were paraded around the city walls for all the inhabitants—and Marius the Younger—to see. The message was clear: Carbo and Telesinus had been defeated. Only Marius and a few Roman soldiers and senators remained to oppose Sulla’s might.

Taking Praeneste

The inhabitants surrendered Praeneste to Lucretius. Marius tried to hide from the Romans in an underground tunnel, but before long he realized that escape was impossible and he committed suicide, ordering one of his slaves to kill him with his own sword. Lucretius cut off the younger Marius’s head and sent it to Sulla, who placed the grisly trophy in the Forum for all of Rome to see. The senators who had fought beside Marius were taken prisoner and executed. The other inhabitants of Praeneste were disarmed and marched out of the gates and onto the open plain beyond. Lucretius selected a few who had helped him take the city and removed them from the group. The rest were divided up into three sections—Romans, Samnites, and Praenestians. By Lucretius’s command, the Romans were pardoned, although he still believed that they deserved death. All the male Samnites and Praenestians were killed; their women and children were left unharmed. After the mass executions, Lucretius ordered the town plundered, a task his soldiers carried out eagerly and effectively.

When Sulla returned to Rome, he brought with him 6,000 prisoners from Antemnae. The battle at the Colline Gate had cost him dearly. Of the astonishing 50,000 men who had died there, many had been his friends and colleagues. In a cold fury, Sulla stood before the Senate—what was left of the Senate—at the temple of Bellona and began to speak in a low voice. While he spoke, the 6,000 prisoners confined nearby were cut to pieces by his soldiers. The screams and shrieks of the victims shattered the air. Sulla continued speaking without varying his tone, dismissing the cacophony as a little matter of housekeeping. He knew exactly what was happening. He wanted the Senate to know that he knew, and that it did not bother him a bit. When he finished, the last cries of the slaughtered were a mere echo.

The Proscriptions of Sulla

The killing would not end there. Sulla’s reign, much like his enemy Marius’s, was bloody and vicious. Lists of “proscriptions” were posted throughout the city. On the lists were the names of Sulla’s old political enemies as well as many Romans whose only crimes were to be too wealthy or to own too much land. The men on the lists lost both their fortunes and their lives, while their widows were expressly forbidden to remarry. Sulla, as the unchallenged leader of the Optimates, allowed free elections to be held and set up new rules that expanded the Senate from 300 to 600 members and prescribed a 10-year interval between consulships to ensure a stable government. But his ceaseless revenge against those who had opposed him far overshadowed any triumph of governance he might have enjoyed in his final days. Even worse, he had provided a working blueprint for ensuing dictatorial generals to force theirs ideals upon a frightened government.

When Sulla retired to his farm in 79 bc, he had already plowed a path—however unwittingly—for another such general, Gaius Julius Caesar, to complete the destruction of the Roman republic. Rome had not seen the last of its civil wars—far from it. The next few decades would feature incessant infighting among the social and political elite of Rome. The bloodbath at the Colline Gate, terrible though it was, would prove to be a mere shadow of things to come.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments