By William F. Floyd, Jr.

Everyone in Washington, D.C., knew the reason Maj. Gen. Ulysses Grant was in town. He had a hard time moving around without people applauding him everywhere he went. Elihu Washburne, a U.S. representative from Illinois, had proposed a bill reviving the rank of lieutenant general, and all of Washington knew who was in line for this promotion.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law on February 26, 1864. Lincoln immediately sent the nomination to the Senate, where it was confirmed the next day. The formal promotion took place on March 9 at a meeting of the cabinet at the White House. Grant later told his wife, Julia, that his only regret at accepting the promotion was that it bound him to Washington. Grant left Washington to retrieve his family, which was still in Nashville, Tennessee, arriving back in Washington on March 23. Grant did not want to have his headquarters in Washington, so after getting Julia established in a house in Georgetown, he set up his command 50 miles away in Culpeper, Virginia, at the headquarters of Maj. Gen. George Meade and the Army of the Potomac.

This placed Meade in a position such as Grant had with Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck while in the West, which was that of being second in command. Meade knew the reason Grant was now with the Army of the Potomac but chose not to make it a point of contention while maintaining nominal command of his army. Meade even offered to give up his command to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman if that was Grant’s wish, but Grant chose to keep Sherman in the western theater.

At that point, Grant prepared his plans for destroying Lee’s army. The presidential election of 1864 made the success of the spring campaign politically important to Lincoln. If the Confederates could deny the Union a decisive victory before the election, there was a possibility a democrat might defeat Lincoln. Lincoln had so much confidence in Grant that he did not interfere with his plans and did not even ask to know them. After more than three years, Lincoln had finally found the right man. His strategy was simply to kill more Southern soldiers than Northerners being killed. To make this plan work, Grant had to keep all his armies moving and to keep the fighting going in all theaters of the war.

Grant’s strategy in the eastern theater was based on a three-pronged attack. Meade’s Army of the Potomac, along with Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s independent IX Corps, was to sweep around Lee’s fortified line and engage him in battle. A second force under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler was to advance up the James River and strike Richmond in an attempt to sever Lee’s supply lines and threaten the Confederate capital. A third force under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel was to march up the Shenandoah Valley, disrupting Lee’s strategic left flank with the goal of further hindering his supplies and communications.

In addition to operations in Virginia, there were two other Union armies operating farther south. Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks would attempt to capture Mobile, Alabama, the last remaining Gulf Coast port in Southern hands. In the meantime, Sherman in northern Georgia would move toward Atlanta to break up General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee and nullify the Peach State as a source of supplies and industry for the Confederacy. Grant also tapped Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to lead the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Over the past five months, there had been nothing but skirmishes in Virginia, but now with winter over that was all about to change. “Wherever Lee goes, there, you will go also,” Grant told Meade.

After the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg in July 1863, Lee faced a daunting challenge rebuilding the Army of Northern Virginia. At the three-day battle, the Army of Northern Virginia lost 15 of its 45 brigade and division commanders. Many of the remaining officers were simply not up to the task of command. Because of Lee’s decentralized style of command, he had to be careful in choosing new officers who would be capable of operating on their own if necessary. Many of the mid-level and senior officers were volunteers who had risen through the ranks as a result of their political connections or the simple fact that they had survived. Lee had to balance these men with formally trained officers.

After completing the reorganization, Lee met at Clark’s Mountain in Culpeper County, Virginia, with his corps and division commanders to plan the upcoming campaign. From this 600-foot summit, the Confederates had a view of the entire Army of the Potomac. Lee was aided in no small degree by the inactivity of the Federal army, though this lack of activity could not be expected to last forever. Earlier in the year Lee had submitted various options for the 1864 spring campaign to Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The plans centered on the role of the Army of Northern Virginia’s I Corps commander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who had left Virginia on September 9, 1863, with 12,000 men to travel by rail to Georgia and reinforce General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. After the Battle of Chickamauga, Longstreet’s force moved into East Tennessee to offset Union advances in that region.

One option called for Longstreet to march to Kentucky, cut Grant’s communications, and assist Johnston. To carry out this mission, Longstreet would need horses and mules to move his infantry. Davis rejected this idea. Another option was for Longstreet to return to the Army of Northern Virginia. This might give Lee enough troops to drive Meade’s army back to Washington. Davis favored the latter plan. Thus, in early April Longstreet moved to rejoin Lee. This gave the Army of Northern Virginia the same basic three-corps structure it had at Gettysburg in which Longstreet commanded the I Corps, Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell commanded the II Corps, and Lt. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill commanded the III Corps. Lee’s cavalry chief, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, remained in charge of Lee’s cavalry.

On May 4, Lee sent a telegram to Richmond that stated, “Enemy has struck his tents. Infantry, artillery, and cavalry are moving toward the Germanna and Ely’s Fords.” The crossing points Lee was referring to were on the Rapidan River. In the upcoming campaign, Lee’s 64,000 Confederates in the Army of Northern Virginia would face 120,000 men in the Army of the Potomac. The campaign, which became known as the Overland Campaign, would produce some of the heaviest fighting of the war.

When Grant met with Lincoln in February, he laid out his plan for defeating the Confederacy. It would be different from anything previously attempted. For three years, the Union Army had been unable to mount concerted offensives against the Confederacy. When these offensives failed, it became standard operating procedure for Union generals to fall back and wait for the next campaigning season. These pauses essentially enabled the Confederates to shift their forces without interference. By striking all of the Confederate armies in the field at once, Grant hoped to grind the Confederacy to a nub.

On the Confederate side, in the spring of1864 would prove to be one in which Lee adopted a new form of strategy to go up against Grant. He changed from his aggressive style to one of a defensive nature in the hope of forcing Grant into a war of attrition, similar to what Grant had in mind. Confederate Brig. Gen. Evander Law expressed awe for the accomplishments of his commander: “General Lee held so completely the admiration and confidence of his men that his conduct of a campaign was rarely criticized.” Weakened by illness, the loss or injury of some of his principal lieutenants, and facing a much larger enemy, Lee would adapt brilliantly. He felt that he understood how Grant operated, which he related to Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon. “He discussed the dominant characteristics of his great antagonist,” related Gordon, noting “his indomitable will and untiring persistency; his direct method of waging war by delivering constant and heavy blows upon the enemy’s front rather than by seeking advantage through strategic maneuver.”

As Grant began his first move, he was aware that Longstreet’s I Corps was some distance beyond the II and III Corps of Ewell and Hill, respectively, and he hoped to bring on a battle before Longstreet arrived. Lee already had decided not to contest the enemy’s crossing of the Rapidan River. He wanted to wait and catch the Army of the Potomac when it entered the Wilderness, where numbers would count for very little. Grant would have to march through the Wilderness in order to travel south from the fords used to cross the Rapidan.

Lee ordered Ewell and Hill to enter the Wilderness and strike the Federals as they marched. On May 5, the two Confederate corps marching from the west ran into three Union corps headed south from the Rapidan. On this first day of fighting in the Wilderness, the Federals managed to get more than 70,000 men into the fight, while the Rebels had fewer than 40,000 men. But the preponderance of Union troops was not an advantage in these dense, smoke-filled woods where soldiers rarely saw the enemy clearly. When the underbrush caught fire, it threatened wounded soldiers with being burned to death. By the end of the day, the Federals had gained a position to attack Lee’s right.

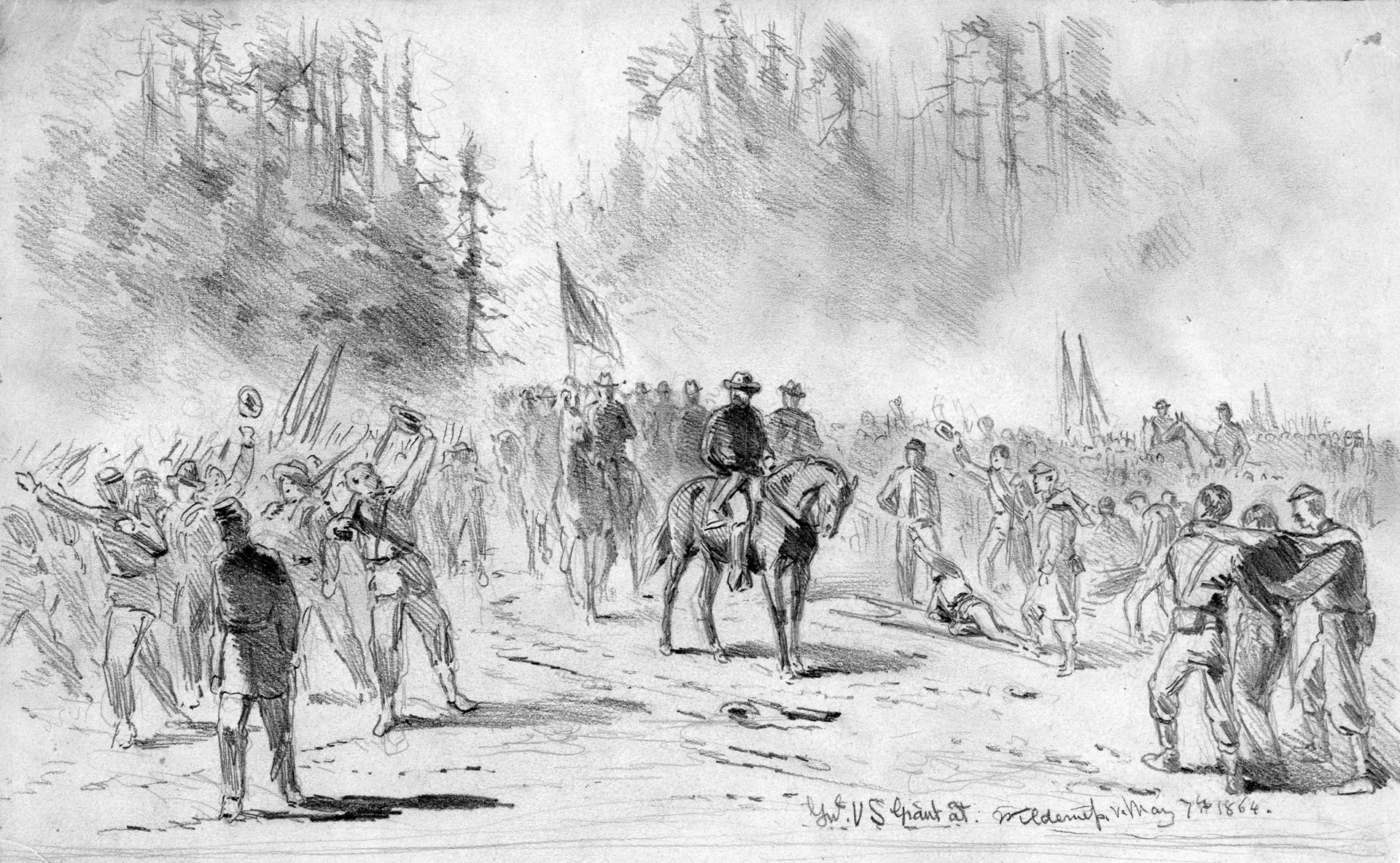

Grant ordered his generals to counterattack at dawn on May 6. Lee also had plans for an early morning attack in this same area. The Yankees attacked first and drove the Rebels back almost a mile through the woods to a location where Lee had his field headquarters. Lee tried to lead a counterattack, but his troops forced him back as Longstreet’s men arrived and stopped the Union advance. Using their knowledge of the area, the Confederates attacked again shortly before noon, driving back the surprised Northern regiments. But the Confederates suffered a major loss to their high command with the wounding of Longstreet, who would be out of action for five months. At the end of the two-day battle, the Federals had suffered 17,500 casualties and the Confederates had suffered 10,500. Under similar conditions, previous Union commanders would have withdrawn behind the nearest river, but not Grant. He ordered Meade to move south. During the night of May 7-8, the Federals marched toward the nondescript village of Spotsylvania in an attempt to get between Lee and Richmond.

Unfortunately for Grant, Lee anticipated the move and won the race to the Spotsylvania crossroads. The Confederates’ race to the crossroads was helped out by roads through the woods, which Lee had ordered to be improved earlier. Lee selected Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, who was temporarily replacing Longstreet as head of I Corps, to lead the march to Spotsylvania. Anderson put his troops on the road but found no good place to stop because of the burning woods and narrow byways. His command traveled all night without stopping. The Federal advance on the Brock Road was slowed in the face of scattered but determined resistance from Confederate cavalry. The day after the Battle of the Wilderness, Rhode Islander Elisha Hunt Rhodes no longer had any qualms about Grant: “If we were under any other general except Grant, I should expect a retreat, but Grant is not that kind of a soldier, and we feel we can trust him.”

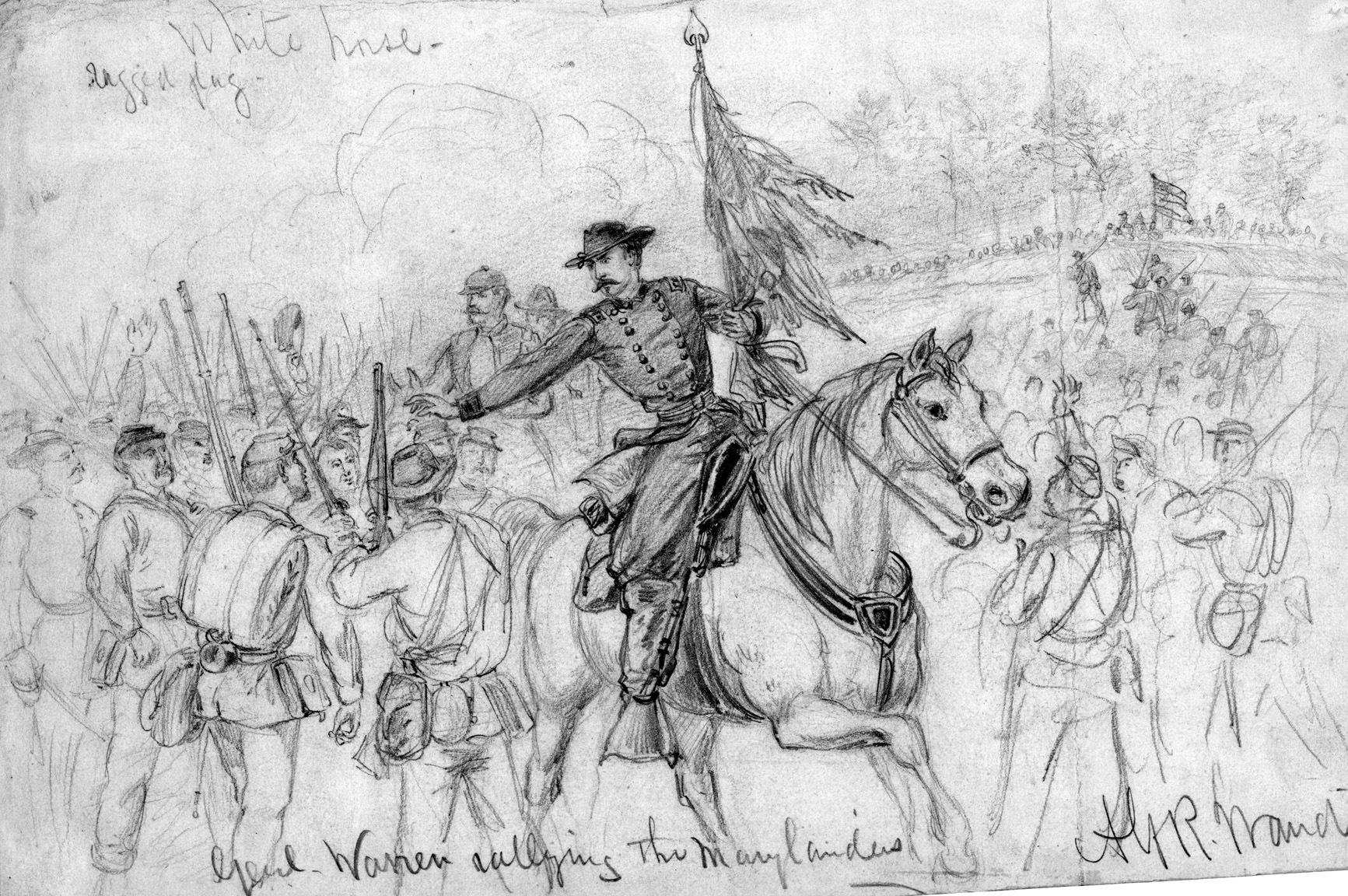

The action around Spotsylvania rapidly accelerated on the morning of May 8. Sheridan’s troopers began advancing toward Spotsylvania before dawn, forcing Stuart’s two divisions to retreat along the Brock and Fredericksburg Roads. Appeals from Stuart for help went to Anderson. Anderson quickly sent two infantry brigades and an artillery brigade to stabilize the Brock Road. Anderson also occupied the town and turned his attention to Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren’s advancing V Corps. The Confederates dug in atop Laurel Hill and waited for Ewell’s II Corps.

Warren knew he had to knock the Rebels off the hill to take the crossroads. The Federals advanced toward the hill in the mistaken belief they faced only cavalry. A heavy ripple of musket fire showed that there was much more than cavalry on Laurel Hill. The Federal troops had advanced to a point approximately 50 yards from the Confederate works when Brig. Gen. John Robinson and Colonel Andrew Denison of the Union V Corps were shot from their horses. Seeing the officers shot, many of the enlisted men began to waver. Warren tried to rally the retreating Federals by grabbing a regimental flag and using it as a rallying point. Despite his best efforts, this was the end of the advance.

On May 9, all three of Lee’s corps arrived in the Spotsylvania area and started to construct extensive field works. At Union headquarters, Meade and Sheridan got into a heated argument with Meade accusing Sheridan of incompetence. Sheridan claimed that he could whip Stuart. Meade went to Grant with this claim and Grant told him to go ahead and make good on it.

Neither army rested during the night of May 8-9. Rebel infantry dug trenches with bayonets, plates, and cups and stacked timber and fence rails, packing dirt between them. Grant also had his troops working to reinforce their own lines. The opposing forces in some places were just a few hundred yards apart. Soldiers on both sides braced themselves for the hard fighting that lay ahead.

Meade’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, had a grim assessment of the Confederate fortifications. Reconaissance was difficult, and Humphreys determined that the Confederate field works were stitched so tightly together there was “scarcely any measure by which to gauge the increased strength thereby gained.”

On the morning of May 9, Maj. Gen. Jubal Early, who commanded a division in Ewell’s II Corps, deployed his troops in a line that stretched from the Fredericksburg Road to the east of Spotsylvania Court House. Union VI Corps commander Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick was supervising the placement of artillery batteries when he was killed by a Confederate sniper. Grant bemoaned the loss to the Army of the Potomac. It was, in his words, “greater than the loss of a whole division of troops.” Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, who commanded the First Division of VI Corps, replaced Sedgwick as VI Corps commander.

The two opposing armies slowly consolidated their positions. The length of the lines was now approaching seven miles. At first Grant was unwilling to send troops against the strong Confederate defenses. But when he began receiving reports indicating Lee was increasing his troop strength on his right, Grant ordered Union II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock to flank the Confederate left. Hancock’s men moved out at 3 pm on May 9, but they almost immediately ran into trouble. The major problem was the difficult terrain, which was uneven and dense. Hancock aborted the operation at 8 pm. The movement, however, was not a complete waste as it caused Lee to shift several units to Block House Road to shore up its defenses. This left only one division to watch Burnside, bringing to an end to the troop movements of May 9.

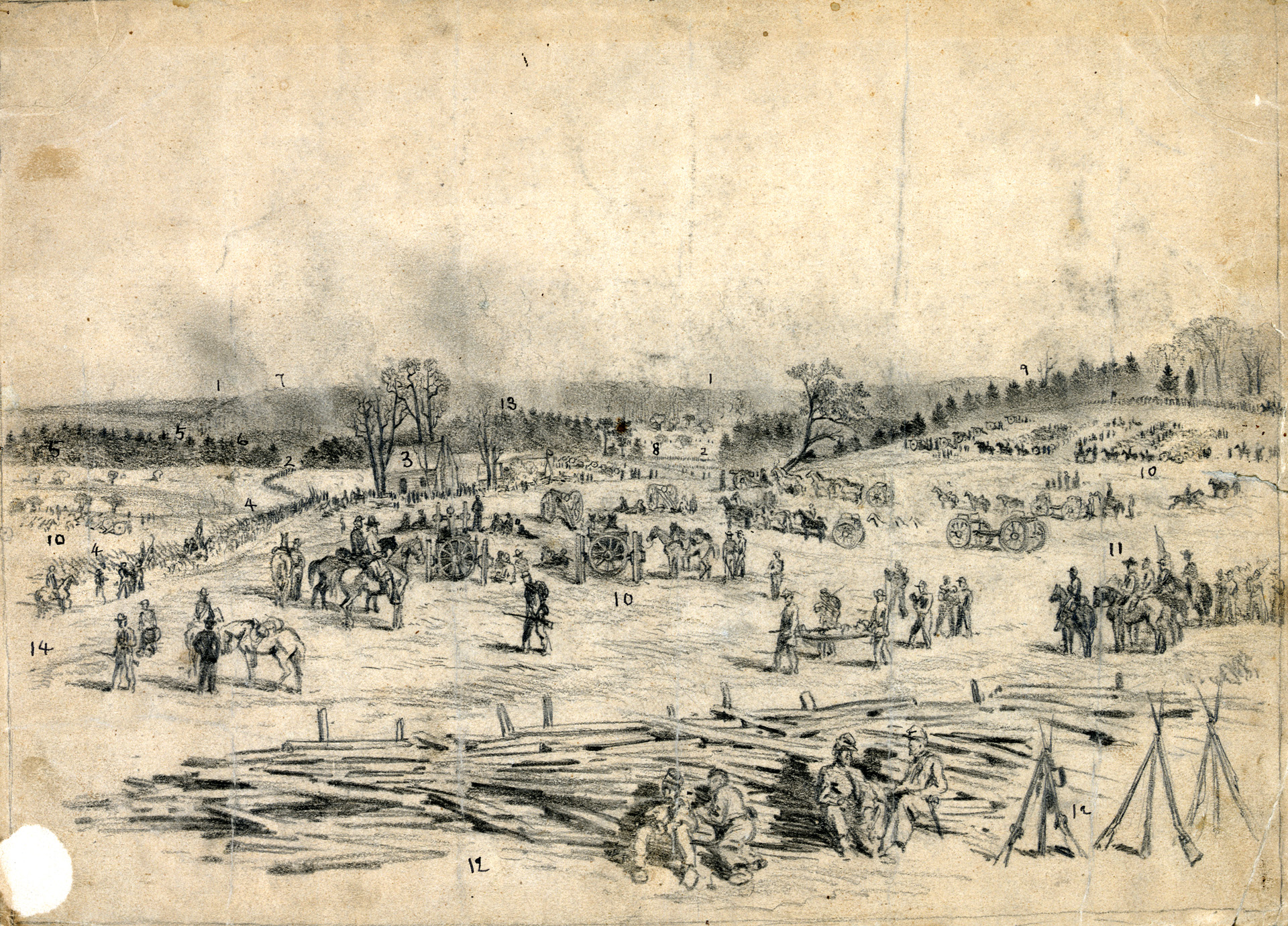

The plan for May 10 was complex and required coordination beyond anything that the Federals had achieved thus far in the campaign. Hancock was to resume his previous day’s turning maneuver across the Po River at the Block House Bridge and attack the western end of Anderson’s fortified line. As Anderson’s line fell apart, Warren’s V Corps and Wright’s VI Corps were to charge Laurel Hill. In the meantime, Burnside was to renew his movement down the Fredericksburg Road into Spotsylvania.

Lee’s plan also involved Hancock. Brig. Gen. William Mahone had succeeded to command of Anderson’s division of the Confederate III Corps following Anderson’s transfer to lead the Confederate I Corps. Mahone had ordered his men to build strong defensive positions on the Po’s eastern bank. With Mahone pinning Hancock in place, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth was to lead his division across the Po River a few miles to the south and fall on Hancock’s lower flank.

The night of May 9-10 was tense for Hancock. His engineers toiled to build a bridge across the Po. At daybreak, Rebel guns began firing from across the river. The Confederate artillery fire was a little too close for comfort for Hancock’s soldiers positioned on the finger formed by the Po. After surveying the situation, Hancock decided that it would not be a good idea to storm the bridge.

The most significant attack of May 10 came about in the late afternoon as Warren reported that he thought a direct frontal attack could be successful. Grant agreed, and by 4 pm Warren’s divisions were moving toward Anderson’s line with Wright on his left and Hancock on his right. As the Union attackers came forward, Southern batteries raked the Union lines. Wright was shocked by the initial attack. He formed a special force to attack the so-called Mule Shoe salient. Colonel Emory Upton was given the responsibility for leading 12 regiments in an assault on the Confederate position.

The New York native’s attack began with a bombardment by heavy Union guns. Upton’s men got within the Confederate entrenchments and were able to capture approximately 1,000 Rebel prisoners. But supporting attacks by Hancock and Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott were unsuccessful. For this reason, Upton withdrew his troops.

On Wednesday, May 11, Grant had breakfast with Washburne, who had accompanied the army since crossing the Rapidan. Washburne was returning to Washington that day, and he asked Grant if he could give him a statement for Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Rather than send a message to the president, Grant said he would send a letter to Army Chief of Staff Halleck. “I generally communicate through him, giving the general situation, and you can take it with you,” said Grant.

“We have now ended the sixth day of very heavy fighting,” Grant wrote to Halleck. “The result to this time is much to our favor. But our losses have been heavy, as well as those of the enemy.” He ended the message with a phrase that would become famous. “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Grant’s message was soon seen in newspapers across the North.

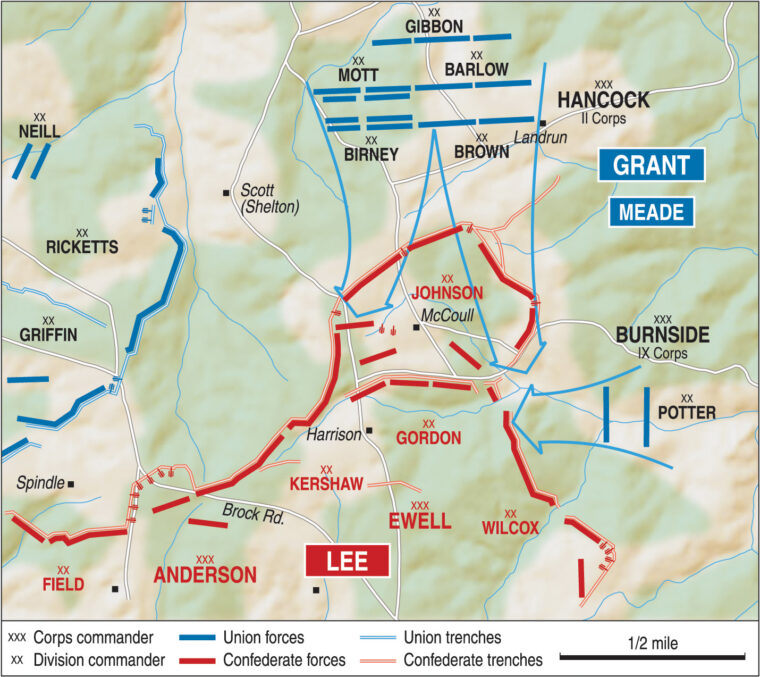

Grant spent the rest of his time on May 11 inspecting his lines and planning the next day’s attack. Grant concluded that the Brown House, north of the Mule Shoe salient, would make an excellent point from which to assemble a massive attack on the salient, which still protruded from the Confederate front around the McCoull and Harrison Houses.

Union staff officers rode in a heavy rain to reconnoiter the ground over which the attack would be launched. Not only did the rain continue throughout the night, but a dense fog formed. Still, Grant was determined to make an attack the next morning. The salient, packed with enemy soldiers, seemed like the spot to hit and snare a lot of Rebels. Defensive lines were improved, supplies were topped off, and the men rested.

Grant issued orders for his offensive plan at 3 pm that day. He decided that Hancock’s II Corps would deliver the main blow at the apex of the salient. This would mean a night march to just north of the salient to the left of Warren’s position. Wright and Warren were to keep close contact with the Confederates, and Hancock would begin a two-division attack in conjunction with Burnside’s IX Corps. Staff officers from Grant’s headquarters were to be sent to assist both Burnside and Hancock and to prod Burnside if necessary.

Lee spent May 11 adjusting his lines, resting his men, and trying to discern Grant’s next move. Meanwhile, cavalry from both sides clashed at Yellow Tavern on the Brock Road just a few miles north of Richmond. Heavily outnumbered, Stuart formed his two brigades to confront Sheridan’s powerful cavalry. Intent on destroying Stuart, Sheridan attacked with four brigades. The Confederates stubbornly resisted in hand-to-hand fighting at crucial points. At 4 pm, Brig. Gen. George Custer’s brigade joined the fight.

At that point, Stuart rode forward to encourage his men. In the mounted melee, Stuart received a severe chest wound, and he died the following day. The death of Stuart was a huge loss for the Confederacy and a personal tragedy for Lee. The fighting continued for another hour before Sheridan withdrew.

Grant had instructed Meade to begin the attack at 4:35 am on May 12 when the early daylight would make the advance possible. Grant had decided to use a large force to attack what appeared to be a vulnerable section of the Confederate line on the northern portion of the salient where Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s division of Ewell’s II Corps was located. Lee had withdrawn his artillery based on information that Grant was planning to withdraw toward Fredericksburg.

Confederate soldiers in the Mule Shoe heard a heavy rumble coming from the direction of the Union lines. The heavy rumble meant either that the Federals were moving around Lee’s flank once again to fight somewhere else or that they were positioning forces for a major assault. Brig. Gen. George “Maryland” Steuart believed the Federals were massing for another assault similar to the one at dusk on May 10. He sent a request to Johnson asking for the return of his artillery support, which had been withdrawn from the front lines for fear it would be captured. The request went up the chain of command. Ewell agreed to the request, and Confederate artillerymen began bringing 22 guns back to the Mule Shoe just before dawn.

The Union advance encountered Confederate pickets but soon ran them off. Hancock and Wright launched the massive frontal assault right into the salient. Once the parapets were in sight, the advance turned into a disorderly rush forward in hopes of catching the defenders unaware. Obstructions 100 yards from the main line were hastily thrown aside, but by now the enemy was growing aware and began firing. The Rebel artillery was manhandled into position. The cannoneers opened up on the attacking Yankees. The Confederate artillerymen were able to fire only a single volley before being surrounded by Yankees.

The fighting became so intense that the area became known as the Bloody Angle. The scene was one of absolute chaos with soldiers fighting hand to hand with bayonets and clubbed muskets. Nearly all of the Confederates in the salient were captured, including Steuart and Johnson. In the course of the melee, Lee offered to lead a counterattack, but he was prevented from doing so by his men, who shouted, “Lee to the rear!”

The Confederate counterattack fell to Gordon. Aided by Early, Gordon succeeded in driving back Hancock’s forces. By 6:30 am, though, Union Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Neill’s division of Wright’s VI Corps advanced on the Confederate left. Even though Gordon’s attack had been successful, the Yankees had not been driven out of the rim of the original Mule Shoe. The fighting at the Bloody Angle continued throughout the day and into the night with casualties piling up on both sides. Union Generals Wright and Warren both advanced into the Confederate line but had to fall back with heavy losses. Both sides reinforced their positions.

The Rebels had surrendered in droves during the attack. Two brigades in Johnson’s Division, those of Colonel William Witcher and Steuart, were gone in minutes. Both Steuart and Johnson were taken prisoner. More than a dozen cannons were taken, and a half mile of the Mule Shoe was cleared. Half a dozen Confederate brigades were driven back. Hancock was ecstatic when he sent word to Meade.

Union guards marched the approximately 2,000 Rebel prisoners to the rear. They took Johnson directly to Meade and Grant. Meade knew Johnson from West Point, and Grant remembered him from the Mexican War. After a pleasant conversation, Johnson was led away to be exchanged for a Union prisoner. Steuart’s experience was different. He was first mistaken for Jeb Stuart, and then he was forced to walk to the rear after refusing to shake hands with Hancock.

Lee tightened his line. Realizing at last that the Mule Shoe was too exposed, he ordered a new line dug across the base of the salient. Lee’s doubts about his ability to maintain the salient were not shared by his men, who felt increasingly confident as the day wore on. Ironically, it was Grant’s corps commanders who became overly cautious. They feared a Rebel counterattack. Grant reluctantly felt that there was no point in trying to mount another assault or to make plans for a renewed attack the next day. Although the day had begun with great promise, it ended with a whimper when Grant’s commanders were unwilling or unable to attempt another assault.

The sun rose on May 13 to an eerie silence. Colonel Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin quietly approached the Bloody Angle and observed the carnage. Bodies were crammed together, some stacked on one another. One Rebel lay sprawled against an embankment, his head gone and the flesh burned from his neck and shoulders by a mortar shell. Adjutant Charles Brewster of the 10th Massachusetts said he saw one man “completely trodden in the mud so as to look like part of it and yet he was breathing and gasping.” A section of Union artillery faced the Bloody Angle no more than 100 yards away. Its horses were still hitched, dead in the mud, and the drivers in their saddles were also dead. The gunners, also dead, were propped up on ammunition boxes. They looked so natural that an officer touched them to persuade himself that they were not alive.

At 5:30 am on May 13, Wright informed Grant that he had occupied the Bloody Angle, but no Confederates were found, at least any that were capable of fighting. Grant had to determine where Lee had gone. If Lee was falling back on Richmond, Grant would want to pursue without delay. Hancock’s skirmishers had advanced past the McCoull House before they encountered Lee’s first pickets. Grant concluded by 6 am that Anderson was still in possession of Laurel Hill and that Early’s corps still stretched across the Fredericksburg Road. The change was that Ewell had pulled back from the salient and apparently deployed in a new line a short distance away.

By 10:30 am, Hancock was satisfied that Ewell had assumed a relatively straight line from Anderson’s right to Early’s left and was in an exceptionally strong position. The casualties of May 12 rivaled those of either day in the Wilderness. The total killed, wounded, or captured on that day for both armies was approximately 17,000. Grant had little to show for his efforts. At the end of eight days of extremely brutal combat, the two armies stood in much the same relative positions as when they had started.

Grant’s performance in commanding his army from May 7 to May 12 brought mixed reviews. He repeatedly tried to establish a relationship with an army whose style of fighting was nowhere near as aggressive as his own. To add to Grant’s problems, he confronted for the first time an adversary whose aggressiveness matched or perhaps exceeded his own. To Grant’s credit throughout this difficult period, he stayed true to his objective of destroying Lee’s army.

While his men worked in burial parties or slept, Grant began plotting his next move. Instead of a general attack, Grant decided to load up on the left of his line with all four corps in an attempt to overwhelm Lee’s right flank. Wright and Warren were set in motion to move below Burnside and attack across the Ni River at 4 am on May 14. The troops were to begin their movement at 8 pm on May 13. Almost immediately, everything started to go wrong. Warren’s corps did not get started until around 10 pm. Almost immediately it ran into rivers of mud and began to bog down. The line became strung out, and the attack was aborted. The only significant action was a confused battle for Myers Hill. Meade was at the hill when the Rebel force attacked, driving the angry general and his troops from their position. There were numerous troop movements on both sides during this period.

The next clash occurred on May 18 when Wright and Hancock attacked Ewell but were stopped by the abatis at the Confederate trench line. On May 19, Ewell’s II Corps attacked the Union left at Harris Farm. Ewell eventually retreated. Over the next few days, there was movement south by both armies, bringing the fighting around Spotsylvania to a close. The second battle of the 1864 campaign took much longer than the fighting in the Wilderness, partly due to the bad weather, but was at times it was equally brutal.

Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter, one of Grant’s aides, never saw anything to equal the fighting on May 12. “Rank after rank was riddled by shot and shell and bayonet thrusts, and finally sank, a mass of torn and mutilated corpses; then fresh troops rushed madly forward to replace the dead and so the murderous work went on,” wrote Porter. “Guns were run up close to the parapet, and double charges of canister played their part in the bloody work. The fence rails and logs in the breastworks were shattered into splinters, and trees over a foot and a half in diameter were cut completely in two by the incessant musketry fire. We had not only shot down an army, but also a forest.”

As Grant moved south and east, he was thwarted by the Confederate army at the North Anna River, Totopotomoy Creek, and Bethesda Church. By the end of May, Grant had reached a crossroads northeast of Richmond called Cold Harbor. It was here that 59,000 entrenched Rebels faced 108,000 Federals along a front that stretched for seven miles. Once again Lee had anticipated Grant’s moves, and the Confederates had established an extremely strong position.

“The rebels are making a desperate fight and I presume will continue to do so as long as they can get a respectable number to stand,” Grant wrote to his wife after the fighting on June 1. On June 3, the Army of the Potomac launched a massive assault that failed miserably. Grant lost approximately 7,000 men in 10 minutes.

Although the battles of the Overland Campaign were considered inconclusive, Cold Harbor was a victory for Lee. The Federals suffered 7,000 casualties while the Confederates had less than 1,500. Grant later admitted that he should never have ordered the attack. The fighting on June 3 nearly destroyed three Union corps and brought to an end a month of incessant campaigning. Over the course of the Overland Campaign the Army of the Potomac had suffered 50,000 casualties, which was equivalent to 41 percent of its total force, and the Army of Northern Virginia had suffered 32,000 casualties, totaling 50 percent of its entire force.

The losses for the South were much more consequential because their casualties could not be as easily replaced as those of the North. The losses for the Union, however, did have an effect in that they diminished the morale needed to finish the war. Grant flanked Lee one more time as he began his move toward the railroad hub of Petersburg, where a 10-month Union siege of the city began. During the siege the Army of Northern Virginia was bled to exhaustion. In the end, Grant’s resources, manpower, and inexorable strategy overcame Lee’s brilliant defense.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House saw some of the most brutal and desperate fighting of the war. Grant’s strategy for the campaign was to hold Lee if he could not defeat him. This would allow Sherman to subdue Georgia and march north through the Carolinas to link up with the Army of the Potomac.

Grant had failed in the seven-week Overland Campaign to either destroy the Army of Northern Virginia or capture the Confederate capital at Richmond. Grant’s casualties averaged 2,000 men a day over the course of the campaign from May 4, 1864, to June 24, 1864. But Grant differed from previous Federal commanders in one important aspect. He would not back off.

Beginning with the Overland Campaign, the Army of the Potomac would never retreat again. This policy would set the stage for the final phase of the war. When Grant crossed the Rapidan River on May 4, the war would change for both Grant and Lee. Each was up against an opponent who was equally determined to win the war. In the end, Grant won by bringing to bear the North’s overwhelming advantage in manpower and economic strength.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments