By Glenn Barnett

In 1939 the one thing that Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin could agree on was the partition of Poland. Czarist Russia and Prussia had done so three times in the 18th century, and the protocol and mechanics were well known. The Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact negotiated by the foreign ministers of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, and named for them, was a standard nonaggression pact that contained a secret agreement—the amicable division of the country that lay between them. But the Nazis and Soviets would add their own ruthless twist to the partition: genocide.

Because of previous partitions, Poland had been a part of Russia at the turn of the century. When the Communists bludgeoned their way to power in Russia in 1917, Wladyslaw Anders joined with other Polish soldiers to support a new Polish state. He fought against the Red Army in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1920 and participated in the decisive Battle of Warsaw, which assured Polish independence.

On September 1, 1939, the German Army created an “incident” and invaded Poland. On the 17th the Russians attacked from the east. The two armies advanced to prearranged positions, and Poland ceased to exist for the duration of the war.

Wladyslaw Anders, now a general, fought against the invaders as long as he could. He commanded a cavalry unit against the Germans. When the Russians attacked he shifted his army to face the new threat and kept fighting until he was captured.

Anders began his career as an officer in the czarist army in World War I with command of an all-Polish Corps.

In 1939, when he was trapped between his country’s enemies, he surrendered to the Soviets. The next year and a half of his life was spent in prison because he refused to sign a document expressing his willingness to join the Red Army. For that he was kept in an unheated, windowless cell during the bitter winter of 1939-1940. Temperatures outside dropped to -22 degrees Fahrenheit, causing Anders to suffer from frostbite. In the spring, still refusing to sign, he was transferred to another prison, where he was kept in solitary confinement with a bright light shining on him day and night. He was incessantly interrogated and often denied food. For a time he was held in the notorious Lubyanka prison in Moscow.

Stanislaw (Stan) Cybulski was 13 in 1939. He lived in the village of Medyka on the banks of the San River, just inside the Soviet zone of occupation. Before the war Stalin had uprooted potentially rebellious people in the Soviet Empire and sent them to Siberian labor camps. The people of eastern Poland were to be next. Any man considered to be a leader was shipped out first. In February 1940, 220,000 men, women, and children were deported. Stan’s father was sent to a labor camp near Murmansk on the White Sea. Stan, along with his mother and two sisters, was sent to a labor camp in Siberia. The brutally cold and crowded train trip lasted three weeks. Initially they were housed in a drafty hut with more than 200 other people. There were only three small wood-burning stoves in each hut. Spanish inscriptions on the wall told of the former occupants, prisoners from the Spanish Civil War.

In April 1940, 320,000 more Poles were shipped by rail to Kazakhstan. In June and July, 240,000 more were removed from Poland. These were mostly civilians, and their fate was to work on collective farms and in mines and factories. Polish sources estimate that during the war 1,700,000 Poles were uprooted from their homes by the Soviets and that one million of those died or were unaccounted for while in Soviet custody. One of them was Stan Cybulski’s older sister.

The military was dealt with separately. Estimates of the number of Polish military personnel who fell into Russian hands range from 200,000 to 300,000 men. The officers were separated from enlisted men and kept in separate camps.

Stan Cybulski, too young to work (the minimum age for workers was 15), was sent to school with other Poles and Russian youth from a local farm. Instruction was in Russian.

It was not so easy for his mother. The local industry was lumber. Trees were felled and dragged to a makeshift steam-operated sawmill. Mrs. Cybulski and other women were made to hand-saw timber and haul water for the steam engine. After school Stan would help his mother with the chores. Sometimes he would search the nearby woods for mushrooms and berries to supplement his family’s meager diet of bread, potatoes, and cabbage. Their only meat came if a workhorse died.

The prisoners were allowed to build new huts for themselves according to Soviet specifications. The new accommodations slept 10 or 11 people from three families in one room. Each room had its own stove.

The surprise German invasion of the USSR on June 22, 1941, changed everything. Desperate for manpower and allies, the Soviet government recognized the London-based Polish government in exile. They then forged an agreement for Polish prisoners in the USSR to form a military unit with a Polish commander but subordinate to the Red Army. The Polish government chose General Anders to lead their new unit.

On August 4, Anders was brought directly from his prison cell for a meeting with NKVD chief Lavrenti Beria and told of his new assignment. He was then given a comfortable apartment in Moscow.

The Soviets freed the Poles from their gulags and labor camps and encouraged the formation of a Polish Army from these tired and hungry men. Funding for the new army in the USSR was paid for by means of “credits” or loans extended by the Soviets, to be reimbursed by the Polish government and Great Britain.

Among those released was Stan Cybulski’s family. Miraculously, his father had located them from his distant camp on the White Sea and made the long train ride to be reunited with them. From there they joined a mass Polish exodus to the south, where the army was forming up. It was not easy. Soviet authorities did little to facilitate the move. Every Pole was on his or her own. Many had to work or beg to afford passage on trains headed south. Some died of exposure or hunger along the way. The Soviet Union was a vast land, and no one was quite sure where the new Polish Army was. Stan Cybulski’s father worked for a few weeks on a road construction gang in Kyrgyzstan to purchase railroad tickets for the next leg of his family’s journey.

Not all Poles were released, however. Thousands were retained to work in factories and mines and on collective farms, or conscripted directly into the Red Army. But for those who did manage to join Anders, salvation was at hand.

Anders was given extensive leeway by the Soviet government in the formation of the new army. His reputation and fluent Russian opened doors for him. He was even allowed to meet with Soviet leader Josef Stalin. He insisted that the families of soldiers be allowed to join them so that the men would not have to worry about them. Stalin agreed.

The initial understanding was that Anders was to enlist a force of 10,000 men to be armed by the Soviets and sent into battle by October 1, 1941. The six-week window for enlisting, arming, and training was clearly unrealistic; Anders did not think his men would be ready for battle until June 1942. Anders was right––the men who were being recruited came straight from the wretched labor camps. They were malnourished and diseased and clearly not ready to fight.

Supply problems, too, were rampant. By November, Anders had recruited 44,000 soldiers but had only 160 rifles. More than 40 percent of the men had no shoes. Food was scarce throughout the entire country, and the Soviets were reluctant to feed 44,000 men and their families, who were not fighting. Stalin argued that they were to be fed from rations sent by Great Britain through Iran, but these were slow in coming. Soviet authorities then ordered Anders to reduce his army to 30,000 men and send the rest to labor camps. Anders refused. The Soviets retaliated by providing rations for only 30,000 men. Anders divided what he received among all of his soldiers and civilians.

By February 1942, Anders’s men had received British-style uniforms and small arms. Food shipments also improved. At least one of his divisions was ready for battle and the Soviets insisted that they be sent to the front at once. But the division had no heavy weapons. The Soviets informed Anders that these would be provided at the front, but the Polish general insisted that his men needed training in using these weapons before going into battle.

In March, Anders met with Stalin again. He now had two divisions armed and trained, but recruits kept coming in and his total manpower was at 70,000, not including families. Because of nationwide food shortages, Stalin was not willing to feed more than 44,000. The rest were to be sent to Iran where they could be fed and trained. The goal was for them to return to Russia to join the fight. In April 1942, 30,000 soldiers and 12,000 civilians left the Soviet Union for Iran. Some traveled overland by truck, but most were shipped across the Caspian Sea in overcrowded boats. Stan Cybulski and his family were among them.

Up to 40 percent of the evacuees to Iran were infested with lice and other vermin. When the refugees came ashore in northern Iran, their clothes were taken from them and burned. They were deloused and given new clothes. Most were also diseased with typhus and ailments associated with malnutrition. The weakened evacuees had to be careful what they ate; too much rich food all at once would kill them. Their new diet contained a great deal of rice, which was easier to digest than meat.

As the soldiers of the former Polish Army began to swell the ranks of this new army, the junior officers were unaccounted for. No one had seen them since Soviet authorities separated them from the enlisted men. The Soviets kept making excuses for their absence.

While the first evacuation to Iran was taking place in April 1942, the Germans announced that they had found a mass grave of Polish officers and civilians in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk. The death toll there and in three other camps would eventually be calculated at 14,000 officers and more than 7,000 civilians. The massacre, according to the Germans, was committed by the Soviets. Stalin’s government denied everything. Yet only 12 days after the German announcement, the Soviets broke off relations with the Polish government in London, which had demanded a full investigation of the incident at Katyn.

Anders and his men knew instinctively that the report of the massacre was true. They had not seen these officers since they were separated from their men late in 1939. Most of Anders’s men, like him, had suffered in Soviet prisons and labor camps. They knew quite well that Stalin was capable of such a thing. Anders was all the more anxious to get his men out of Russia. The Russians, fearing an armed enemy loyal to the Polish government in London within their borders, were happy to see them go.

Before the Katyn massacre was revealed, the Red Army did not want any more Polish fighters to leave the country for Iran. After that event, and the break in relations with the London Poles, they supported the departure. Soviet authorities did not like the idea of a disaffected armed force, loyal to the exiled Polish government within their borders.

In July, the second evacuation took place. This time, 70,000 Poles—including 25,000 civilians and General Anders—made the long trip to Iran. In all, the official total of evacuees reached 115,000.

When Anders was negotiating with the Russians to send his men out of the country, the Soviets insisted that Jewish soldiers not be included in the evacuation. He ignored their demands. As many as 4,000 Jewish soldiers and 3,000 Jewish civilians were included in the evacuation to Iran.

The Poles who remained in the Soviet Union would either be conscripted into the Red Army or continue to labor in fields and factories for the duration of the war. For many of them it was a death sentence.

Anders and his fledgling army made their way to Iraq for further training. There they were joined by the Independent Carpathian Brigade, which had formed in Britain in 1940 from Polish exiles who had escaped to the West. They had fought in North Africa and distinguished themselves at Tobruk. They now became a part of Anders’s army.

The civilians who had been brought out of Russia were sent to refugee camps in India and Africa. Stan Cybulski’s family and 4,000 others ended up at Camp Masindi in Uganda. There they built a redbrick church that is still used by Ugandan Catholics today. Stan returned to school where instruction was now in Polish while English, French, and Latin were offered as second languages.

General Anders continued to train and equip his army—only this time, instead of the Russians, he was dealing with the British. Polish exiles had already proven their worth to the British. Before the war Polish scientists had broken the German “Enigma” code and provided that knowledge to the British. Much has been said about the importance of the compromised Enigma code to the Allied war effort.

The Polish Podhalanska Brigade fought with the British at German-occupied Narvik in Norway. Polish pilots swelled the ranks of the RAF during the Battle of Britain, and Polish crews manned up to 27 ships and submarines for the Royal Navy.

Anders wanted to dramatically increase Polish participation in the war effort. He proposed creating a Polish Army of two corps. The British countered by insisting that the Poles form a single corps of two divisions, and so the Polish II Corps was born.

From Iraq the Poles made their way to Palestine. While in Palestine, the Polish Army experienced a number of defections; more than half of the Jewish soldiers deserted to be a part of the Zionist experiment. Their military training would be of great service when Israel fought for its independence. One of the Jewish soldiers, Menachem Begin, refused to desert but requested discharge papers from the Polish Army. When he was honorably discharged, Begin remained in Palestine, where he would become a leader in the nascent Jewish state. Many other Jews fought and some died with II Corps. General Anders and his officers knew of these defections but allowed the Jews to make their own choices.

While the Polish Army was going through its long ordeal, the war in the west shifted from North Africa to Sicily and then to Italy. From Palestine Anders’s II Corps was trucked to Egypt, where it was maintained in a huge camp at Quassassin near Suez.

In early December 1943, after talks between Anders and Allied commanders, it was decided that II Corps would be sent to southern Italy under British command to reinforce the Allied forces. Because of the limited space available on a small number of transports, the move took place between December 1943 and May 1944. Things had changed since their last voyage across the Caspian Sea in 1942. Before, they were desperate refugees; now they were a confident army.

Stan Cybulski turned 17 in December 1943 and in May 1944 he left Uganda for Quassassin in Egypt, where he enlisted with the Polish forces in the Middle East and began his basic training.

In Italy the Polish II Corps now numbered 52,000 men in two divisions (the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division with the old Carpathian Brigade at its core, and the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division, consisting of men who had come out of Russia with Anders). There was also an armored brigade, a reconnaissance regiment, an artillery regiment, and a tank division. The II Corps was equipped with 189 tanks, 245 armored cars, 500 mortars, 250 antitank guns, 230 field guns, 132 anti-aircraft guns, and some 3,000 machine guns.

If there was a weakness in the Polish Army, it was that it was cut off from its source of new recruits and reinforcements; no new recruits could get out of Poland or the Soviet Union. Anders’s solution was unorthodox. He let it be known that he would recruit from German POWs. At this point in the war, the Wehrmacht forcibly conscripted men from Poland and elsewhere in their conquered empire. In the Italian campaign the Germans relied on these conscripts to fill their depleted ranks. Anders received permission to interview Poles in German uniform who had been taken prisoner. He would enlist those willing to fight.

The II Polish Corps arrived in Italy in the midst of a stalemate. The Allies had secured southern Italy by the end of 1943 and the Italians had not only surrendered but gone over to the Allied side. The Germans, however, had no intention of surrender. Despite their recent crushing defeat at the Battle of Kursk, they dispatched significant forces to occupy Italy.

The Germans quickly disarmed their former Italian allies and moved forces to the south. At the same time, the Allies, victorious in Sicily, invaded Italy at several places in the foot of the Italian boot. The outnumbered Germans retreated slowly while buying time to fortify a major defense line that made maximum use of the natural terrain— mountains, rivers, and narrow valleys. Called the Gustav Line, it stretched across the entire peninsula. Concrete pillboxes and steel-topped machine-gun nests provided interlocking fire on the approaches to the heights where the Germans had dug in. Naples had to be given up, but Rome was to be protected at all costs.

Meanwhile, the Allies advanced up both coasts of Italy. The U.S. Fifth Army under Mark Clark operated out of Naples and marched along the west coast while the British Eighth Army under General Oliver Leese advanced along the Adriatic coast until it reached the German line anchored on the mountaintop Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino. At that point, the Allied advance stalled completely. The mountain chain around the monastery dominated the Liri Valley, through which ran one of only two roads connecting Rome with southern Italy (Route 6). The other road, which ran along the coast, was the famous Appian Way of antiquity (Route 7). It, too, was dominated by German-controlled heights.

The monastery atop Monte Cassino was one of the most famous in Christendom. It had been established by Saint Benedict in the sixth century and over time had become a repository of valuable art works and a world-renowned library. The mount that it crowned was to become the key to the German defense line.

With the help of the Germans, the movable art and books of the monastery were transported to the Vatican for safekeeping. In all, 120 truckloads of the priceless treasures were secured without loss. It was a wise decision, as the German propaganda machine boasted of their efforts to save the collection from harm’s way. German commanders vowed not to garrison the monastery or the grounds surrounding it within 330 yards. By all accounts they kept their promise.

The Italian winter of 1943-1944 was brutal. Cold rains turned unimproved and unpaved roads to mud while overcast skies neutralized Allied air superiority. The weather and terrain combined to favor the defender.

Between January and May 1944, while the Polish II Corps was arriving in Italy, three major attacks were launched against the mountainous Gustav Line, where a major stalemate had developed. On January 20 the Americans, led by the 36th “Texas” Division, advanced into the Liri Valley while farther east elements of the Free French fought their way into the foothills. The U.S. 34th Division almost overran Monte Calvario (Point 593), a height that dominated the key position at Monte Cassino. These assaults were designed to pull German troops out of Rome to defend against them, while two days later a bold amphibious landing by VI Corps was made at Anzio 60 miles behind the Gustav Line in an effort to cause the Germans to abandon the defenses and flee northward. Counterattacks, however, threw them back with great loss.

The British and American troops put ashore at Anzio were to rush inland, threaten the Germans from behind, and break up their defenses. But Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, the VI Corps commander, fearing a counterattack, decided to dig in to protect his beachead. The pause gave the Germans enough time to counterattack and contain the Allied pocket. Hitler himself ordered the beachhead to be eliminated. In all likelihood the Americans at Anzio would have been thrown into the sea if not for the accurate and deadly support of dozens of offshore naval guns. Long-range German guns dueled with the close-in destroyers and transports. Still, the result was a deadly German ring around Anzio that tied up Allied resources and men.

More landings behind enemy lines might have been successful, but all the available landing craft were now required to be sent to Great Britain to support the upcoming invasion of northern France. The attacks against the Gustav Line also failed.

The frustration of the Americans soon took a horrific turn.

Convinced that the Germans were using the monastery of Monte Cassino for artillery spotting or for the actual mounting of guns, they resolved to destroy it. On February 15, 1944, 200 Allied bombers dropped 576 tons of bombs on the sacred monastery, reducing it to rubble. Yet the outer walls and cellars of the ruin were untouched. There was no evidence that the Germans had violated their word about using the monastery, but they commandeered it after the bombing and used the twisted ruins to rain death on the Allies below. After the war General Clark would write that the bombing of Monte Cassino was “a tactical military error of the first magnitude.”

On the evening of the monastery bombing, the New Zealand Corps joined in the second attack, supported by troops of the 8th Indian Division. The Indian units included the justly famous Gurkha Rifles. Their assignment was to attack the Monte Calvario position that the 34th couldn’t hold. At first all went well, but, as with the first attack, the result was heavy casualties and little to show for it. The Indian Division lost 600 men.

The next attack, in March, was preceded by an eight-hour barrage from 890 guns that consumed 200,000 shells. It had little effect on German positions but created piles of rubble that impeded the progress of the New Zealanders and Indians, who were having another go at it. The offensive lasted for eight days, but in the end only slight progress was made against the German positions. By now the New Zealanders were totally spent.

In mid-March, Anders was visited by General Leese, his nominal boss as head of the British Eighth Army. Leese told the Polish commander that a new offensive was planned and asked if the Polish II Corps was prepared to take part in it. Leese envisioned an offensive along a 20-mile front with the intention of breaking through to the trapped men at Anzio and opening the road to Rome. He wanted the Poles to attack the most difficult position of all, the monastery of Monte Cassino. He gave Anders 10 minutes to think it over.

After a brief discussion with his chief of staff, General Kazimierz Wisniowski, Anders accepted the assignment. He knew that the unit that assaulted Cassino would

suffer the highest casualty rate, but he reasoned that Cassino was the key to the line and would win the most glory and publicity for the unit that could take it. He might suffer casualties equally high against another objective but without the recognition. He also wanted to counter recent Soviet propaganda that the Poles were afraid to fight. Finally, he hoped that news of a Polish victory would spark an uprising in his homeland. For all these reasons, Anders accepted the most dangerous target in the Allied attack.

Military planners chose May as the time for the next offensive. By that time the skies would be clear for aerial operations and the mudmaking rains ended. On April 17, nearly 52,000 Polish soldiers moved up to the line to relieve the exhausted New Zealanders. The movement was done quietly and at night or behind smoke screens because German positions were, in some places, very near and within range of even small artillery. Jeeps were the only vehicles that could navigate the ruined roads, so they carried supplies most of the way. The last part of the supply run up the steep slopes of the foothills was undertaken by 1,200 mules. The mules were last worked by the Indians but had been trained to obey commands in Italian. Observers who watched the Poles now trying to work the mules were amused.

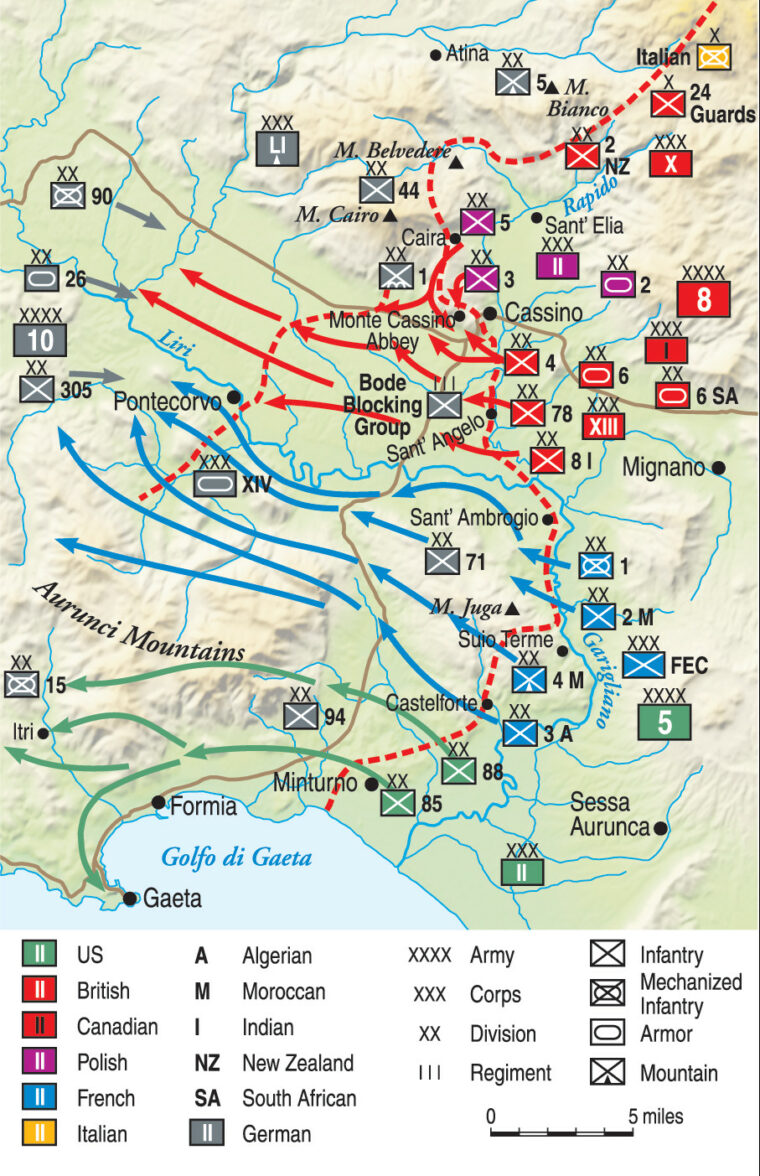

There were to be four large Allied assaults. On the left would be the U.S. Army’s II Corps. Next to them were the men of the French Expeditionary Corps. To their right would be the British XIII Corps and the Polish II Corps. Twenty-one Allied divisions supported by 11 specialized brigades faced a determined force of 14 German divisions and three brigades, though these were not up to full strength.

The Poles faced an enemy reduced and exhausted by continual fighting and the transfer of some of its brigades to northern France. To even the playing field, the Germans used propaganda to play upon the Polish soldiers. Radio Wanda, broadcasting a program from Rome in Polish, aimed to keep the II Corps informed of Soviet moves to gobble up Poland after the war and the British acquiescence to Stalin’s demands. The announcer urged the Poles to desert and join Germany in fighting the Soviets. Few did. It was becoming clear to the men of II Corps that they might never see their homeland again. While fighting for the freedom of the Italians, they were losing theirs.

On May 11 at 11 pm, after weeks of an Allied misinformation plan aimed at convincing the Germans that the next attack would be an amphibious landing north of Rome, 1,600 guns opened up on German positions along an 18-mile front. The Germans were taken completely by surprise.

On the Polish left, four divisions of French soldiers, led by the Moroccan 8th Rifle Regiment, stormed forward and took several hilltop positions south of the Liri Valley by sunrise.

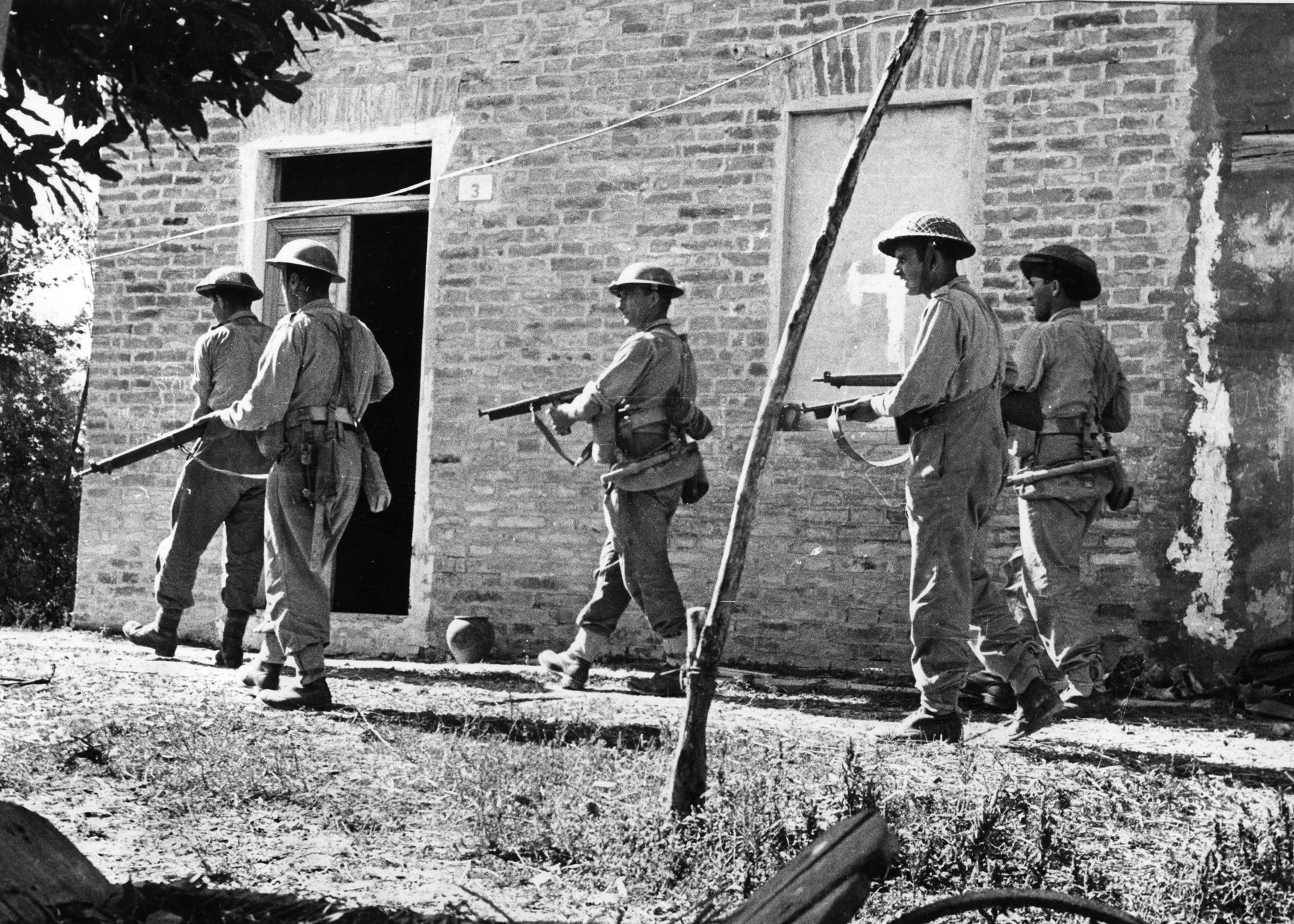

The Poles pushed off for their attack on May 12 at 1 am. Their assignment was to take several hilltops northeast of Monte Cassino and then approach the ruined monastery from behind. The 1st and 2nd Carpathian Brigades were tasked with taking Monte Calvario––a mountain that had already cost the Americans and Indians so much blood. The 13th and 15th Infantry Battalions of the 5th Kresowa Division were to take a height (Point 517) known as Phantom Ridge, or Widmo, by the Poles.

Poppies were noticeably in full bloom on the tortured hillsides and became the symbol of the Polish battle. Even today poppies often adorn the graves of Poles who fell in the battle for Monte Cassino, and a popular Polish song commemorates the event:

The red poppies on Monte Cassino

Drank Polish blood instead of dew…

The Carpathians rushed up the steep slope as closely as they could behind the rolling Allied artillery barrage. They knew that the Germans hid in shellproof bunkers on the reverse slope of the hill. When the barrage was over, they would climb over the ridge and man their machine guns and mortars. If the Poles could not beat the Germans to their posts, they would be easy targets. The Carpathians won the footrace and reached the summit of Monte Calvario before the Germans could man their firing positions. During the day the Germans would counterattack four times without success.

Unfortunately, the Kresowa Division was not as quick in its assault of Phantom Ridge. The Germans reached their firing positions first and rained down artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire on the advancing 13th and 15th Battalions, almost wiping out two companies of the 13th. Supporting tanks got hung up on rocks, hit mines, or were knocked out by German guns. To complicate matters, communications broke down, preventing commanders from coordinating the offensive. That evening the Germans successfully counterattacked and threw the Poles off the mountaintops that they had fought and died for all day; the Polish 5th Division sustained 20 percent casualties. It was II Corps’ baptism of fire.

Anders did not despair. He ordered rear-echelon troops turned into riflemen to fill out the depleted ranks. Cooks, clerks, drivers, anti-aircraft gunners, engineers, and others picked up rifles and machine guns and made their way to the front. Meanwhile, Anders and his staff analyzed their mistakes. They had not scouted beforehand on orders from General Leese, who did not want the enemy to know that fresh Polish troops had arrived at the front. Communications were also a problem between the Poles and the Indian forces on their flank; neither side could understand the way the other spoke English.

A new offensive––the Fourth Battle of Cassino––was originally set for May 15, but Leese postponed it until the 17th. He gave the mission to Lt. Gen. Sidney Kirkman’s British XIII Corps (consisting of the British 4th Division, the British 78th Division, the 8th Indian Division, and the British 6th Armored Division) and Anders’s II Polish Corps. Kirkman was aware of the reckless abandon with which the Poles had attacked on May 11 and told Leese, “Please don’t let Anders attack until we are ready for him or there won’t be any Poles left.”

In preparation, to determine the position of hidden enemy strongpoints, Anders ordered patrols to scout the objective. Roads were cleared to allow tanks to reach the front, artillery concentrations were plotted, and radio gear was reissued.

On the 16th, a patrol of the Polish 5th Kresowa Division discovered that the German defenses on Phantom Ridge were very weak. The Polish brigade commander ordered an immediate but unsupported attack, which nevertheless carried the ridge.

The next day attacks all along the line commenced with the Poles seizing their next objective, Colle San’t Angelo, and holding it all day against German counterattacks. The 3rd Carpathian Division also seized its objective, Monte Calvario, having taken heavy losses in the process. The Poles were exhausted, and casualties were so high that they lost the ability to continue the offensive.

But they had outflanked the enemy positions at Monte Cassino. To prevent it from being cut off, the German defenders were ordered to retreat. Their withdrawal began on the 17th and continued the next day. When the Allies realized that the enemy was fleeing the outposts it had held for the past five months, a race developed between the British and the Poles to reach the shattered monastery. The first to arrive was a patrol of the 12th Podolski Lancers, who raised the Polish flag above the ruins. Anders, a consummate diplomat, ordered that the British flag be raised as well.

II Corps paid dearly for its victory. In that single week of fighting it suffered 4,199 casualties, including 923 dead. The infantry battalions lost 50 percent of their officers and 30 percent of their men. It was a sacrifice that proved that the Poles could and would fight.

There was no time to rest or celebrate. The Germans were on the run, and Allied leaders wanted to keep it that way. The II Corps’ next objective was the town of Piedmonte, a German strongpoint fortified with concrete bunkers, antitank guns, and machine-gun nests. The town anchored the next German defensive line known as the Senger Line.

The initial attack on Piedmont commenced on May 20. Tanks raced toward the fortified town only to be repelled by hidden guns. It would take four attacks and five days to push the enemy out of town.

Meanwhile, other Polish forces stormed the nearby heights including Monte Cairo, the highest peak in the Senger Line. Its capture broke the German defensive positions and opened the road to Rome; others would have the honor of taking the Italian capital. For II Corps it was time to rest and refit. There was little resting, however. After only two weeks in the rear, the Poles were transferred to the Adriatic side of Italy.

In their new sector, Anders took command of three British regiments and some battalions of the Italian Liberation Corps. The victory at Monte Cassino and the Polish general’s stature had convinced the British that he and his officers were capable of commanding British troops in battle.

In a month of combat, the augmented II Corps would advance 75 miles and capture the important port of Ancona. They took 3,000 prisoners during the fighting but suffered 2,424 casualties. Yet more battles lay ahead.

The Germans had fortified the Gothic Line in northern Italy––a line that needed to be erased. II Corps was thrown into the fight, which lasted from mid-June to September 1944. During that time they marched 150 miles, fought eight major battles, and liberated 3,400 square miles of Italian territory.

But there was a growing sadness among the troops. As the Russians began “liberating” Polish territory, it became clear that they had no intention of allowing a free Poland to exist in the postwar world. For most of the men of II Corps, there would be no going home after the war.

The autumn rains and cold weather did not stop the Allied offensive. After a three-week break, II Corps was back in action. Between mid-October and mid-December, they fought their way to the banks of the Senio River, where fighting stopped for the winter.

In February 1945 Stan Cybulski was shipped to Italy, where he would enter officer candidate school. The war would be over before he could join in the fighting.

The offensive resumed on April 9 all along the front. The goal of the Polish forces was the ancient city of Bologna but, for the Poles, the battle began with a bad omen. American bombers misjudged their targets and killed 38 Polish officers and men while wounding 188 more. Anders personally visited the front, where the demoralizing effect of the accidental bombing on his troops was palpable. Despite the tragedy, the advance over the Senio River continued.

By April 21 the Polish flag was raised over Bologna. Within a week the German command in Italy surrendered unconditionally and Germany surrendered soon after. The war was finally over, but Polish soldiers, whose homeland was now occupied by the Soviets, did not share in the general joy of the Allied victory. Although the Allied armies in Italy packed up and went home, the men of II Corps had no place to go. Stalin refused to allow them to return to Poland, and in any event, after their experience in Soviet labor camps, Anders and his men wanted no part of living under Soviet domination.

For Stan Cybulski and the other men from eastern Poland, their homes and towns were now a part of the Soviet Union. Western Poland was ruled by a puppet government answerable only to the Soviets. Returning was out of the question.

The British urged their allies to take the Poles as refugees. The United States refused. Other countries took token numbers. While the British wanted to scatter the Polish soldiers and their families throughout the world, Anders was adamant. He insisted on keeping his army together, and so they were housed in camps around Italy until the British could decide what to do with them. Some of his men felt they should use their weapons to march on Poland and free their homeland. This possibility frightened all the Allies.

After a year on Italian soil, the Italian government felt that the continued presence of a heavily armed force of Polish soldiers within its borders was intolerable. Italian communists were especially uneasy about the vehemently anti-Soviet Poles. Meanwhile, the cost to the British government to continue feeding and housing them was also telling.

In June 1946, II Corps, minus its weapons, began moving to Great Britain; the process would not be complete until the end of October. For Stan Cybulski, Britain would be his home for the next 10 years before moving to the United States. All the while, the British increased their efforts to scatter the Poles throughout the world.

II Corps had proven itself in combat but had not shared in the Allied victory. They themselves, like so many other victims of the war, became displaced refugees. For this victor there were no spoils.

Soon after the battle at Monte Cassino, a cemetery was dedicated to the fallen Polish soldiers who gave their lives to capture the monastery. More than a thousand Polish soldiers are buried there, including General Anders, who died in 1970. At the entrance, an inscription in Polish dedicates the memorial. It reads:

We Polish soldiers

For our freedom and yours

Have given our souls to God

Our bodies to the soil of Italy

And our hearts to Poland

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments