By Mark S. Longo

Their name has been synonymous with murder for almost a thousand years, but few people know the full truth about the enigmatic organization known as the Assassins. Long considered a cult of wanton, drug-crazed killers, the Assassins in reality were far more than a fringe group of political murderers. Devout Muslims who controlled a large domain in the Middle East, their daggers struck down Christians and Muslims alike with equal ferocity. Although their empire was destroyed in the 13th century, the controversial legacy of the Assassins remains alive and well in the modern world.

The Nizari Ismailis, otherwise known as the Assassins, were a splinter sect of Shiite Muslims. Their name derived from their adherence to the teachings of two radical Shiite leaders: an 8th-century Imam named Ismail and a 12th-century Imam named Nizar. The Nizari Ismailis were founded in 1090 ad by the legendary Hasan-i-Sabah. Like the organization he founded, Hasan was a deeply controversial figure, portrayed as both a devout religious scholar and the father of modern terrorism. Under his leadership, the Assassins grew into an influential religious and political power. In the process, they unleashed a wave of murder that terrorized the Middle East for centuries.

Hasan-i-Sabah: Leader of Assassins

Hasan-i-Sabah was born to a devout Shiite family in Persia (modern-day Iran). In the early years of his life, Hasan traveled widely through the Middle East and studied under various Islamic scholars. Along the way, he managed to earn the enmity of a wealthy and powerful Turkish vizier named Nizam al-Mulk. Exactly how this happened remains a mystery. Some scholars say Nizam and Hasan were friends until Hasan betrayed him. Others say that Hasan was a political dissident who conspired against Nizam and the ruling Seljuk Turks. In either case, Hasan was forced to flee to Egypt to escape the vizier’s wrath. He stayed on the run for years, preaching his devout Shiite beliefs to converts in wild regions where Nizam could not reach him.

It was during this period that Hazan came across the mountain fortress of Alamut in northern Persia—the perfect place to base his Nizari Ismaili movement. The fortress was isolated and virtually impregnable to outside forces. Unfortunately, it was already occupied by a Seljuk official. According to Assassin lore, Hasan spent two years infiltrating his followers into Alamut. When the time was right, he smuggled himself inside and offered to purchase the castle from its owner. Realizing that he was outnumbered and had little choice, the Seljuk official took the offer and departed. This marked the beginning of the Assassins as a separate and independent entity.

Once he had taken control of Alamut, Hasan wasted no time in expanding the Assassins’ influence throughout the region. He sent his followers out to convert the surrounding tribes to the Nizari brand of Islam. What could not be taken through conversion was taken by force, and Assassin garrisons were established throughout Persia. The remarkable growth of the sect drew the attention of the ruling Seljuk Turks, who quickly moved to destroy the upstart Assassins. They besieged Alamut in 1092, but were driven off in a bitter battle. Hasan followed his military victory with his first foray into the Assassins’ future hallmark—political murder. He dispatched several of his trained killers (known as fidais, meaning faithful) to the court of his old enemy, Nizam-al-Mulk. Using disguises, they managed to get close enough to plunge their ceremonial daggers into the vizier. The Assassins’ trademark style of murder was born. In later years, some historians would question the role of the Assassins in the death of Nizam-al-Mulk, attributing his murder to political rivals within the Seljuk court. However, even if the murder was committed by Nizam’s rivals, the belief that it was committed by the Assassins showed how far their power—and the fear they inspired—already had spread.

The killing of Nizam and the military victory at Alamut established the Assassins as a force to be reckoned with in the region. Through a combination of military conflict, religious conversion, and political murder, Hasan continued to expand his influence throughout Persia. As the Assassins grew, they encroached ever deeper into Seljuk territory. This led, in turn, to an ongoing state of war between the Ismailis and the Seljuks. The Assassins took control of several fortresses and towns, only to be driven out by the Turks a few years later.

Weathering the War with the Sejuk

The fortress of Shahdiz in the modern Iranian province of Esfahan was a good example of the back-and-forth struggle between the Assassins and the Seljuks. After successfully converting many of the surrounding towns, the Assassins seized the fortress in 1100. It remained under their control for seven years, during which time the Ismaili converts in the region suffered under a withering barrage of Seljuk attacks. In 1107, Seljuk Sultan Muhammed Tapar launched a concerted effort against Ismaili strongholds in his territory. The sultan personally led a massive force against Shahdiz and slaughtered the entire garrison. The local leader of the Assassins was skinned alive and his head preserved as a grisly trophy of the sultan’s victory.

In that same year, the Seljuks made another concerted effort to destroy the heart of Assassin power at Alamut. This time they sent an army bent on vengeance, led by the son of the murdered vizier Nizam-al-Mulk. Another epic siege unfolded, during which many Ismailis in the surrounding area were killed. The Assassins once again managed to break the siege, but the sultan refused to quit. He sent a third army to Alamut in 1109. This time the siege would last eight years and devastate the entire region around the fortress. However, just when things looked worst for Hasan and his followers, fortune turned in their favor. Sultan Muhammed Tapar died, and his army was recalled. Once again, the Assassins had survived against overwhelming odds.

The Devout Fidais

The fact that the Assassins managed to hold their own for so many years against the Seljuk Turks was a testament to their unwavering belief in the righteousness of their cause. Like modern extremist groups, the Assassins had little in the way of a formal military arm. Instead, they relied upon zealous radicals who believed that death in battle led to paradise in the afterlife. The noted traveler Marco Polo described the selection and training of the Assassin fidais in his book, The Travels of Marco Polo: “At his court, likewise, this chief entertained a number of youths, from the age of twelve to twenty years, selected from the inhabitants of the surrounding mountains, who showed a disposition for martial exercises, and appeared to possess the quality of daring courage. When the Sheikh desired the death of some great lord, he would first try an experiment to find out which of his Assassins were the best. He would send some off on a mission in the neighborhood at no great distance with orders to kill such and such a man. They went without demur and did the bidding of their lord. Then, when they had killed the man, they returned to court—those of them that escaped, for some were caught and put to death and the Sheikh knew very well which of them had displayed the greatest zeal, because after each he had sent others of his men as spies to report which was the most daring and the best hand at murdering.”

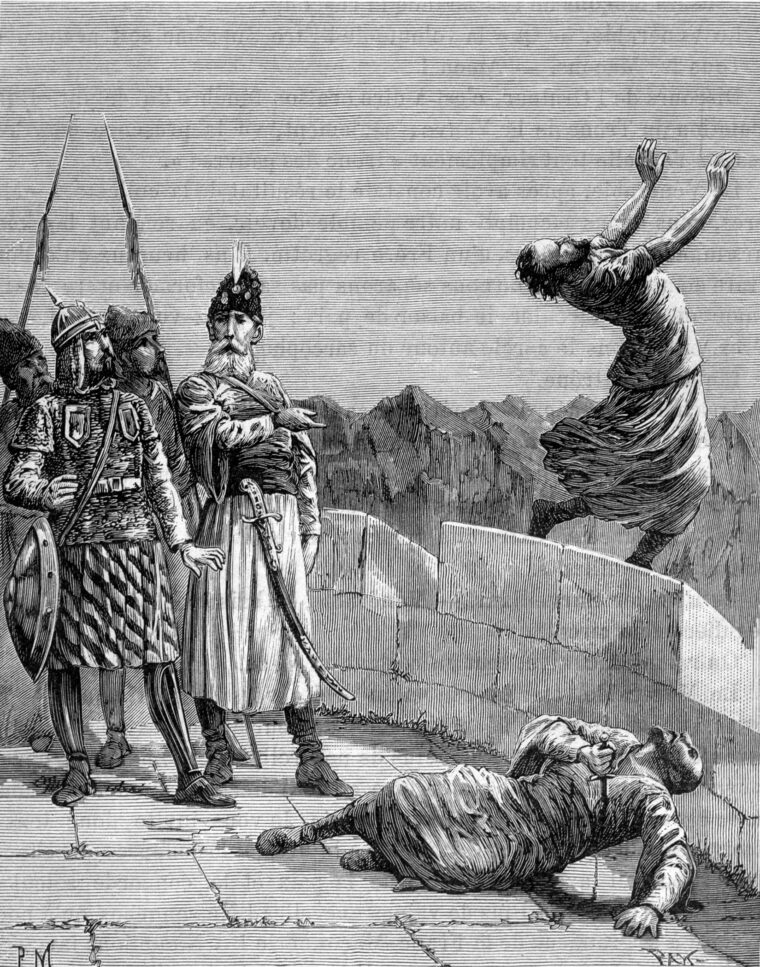

Polo’s account, while colored by centuries of anti-Ismaili prejudice, is a fascinating depiction of these shadowy historical figures. In many ways, Assassin fidais were similar to modern-day suicide bombers. They carried out their missions with no regard to escape or personal safety. However, instead of using an indiscriminate explosive device, the fidais were quite precise in their executions. Armed with only a dagger, they relied on stealth and disguise to get close to their enemies. Patience was a highly regarded virtue among the fidais. Only when the right moment availed itself would they attack, striking down political and military leaders with deadly proficiency.

War and Peace with the Seljuk Empire

The death of Sultan Muhammed Tapar threw the Seljuk Empire into chaos and ushered in a period of uneasy peace with the Assassins. Hasan used this time to rebuild his shattered forces and consolidate his power. A latter-day biographer described Hasan as “perspicacious, capable, learned in geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, magic, and other things.” Ascetic and abstemious, Hasan banned the drinking of wine in his kingdom, and even executed one of his own sons for violating the ban. A second son was put to death for allegedly plotting the murder of a local missionary. The Assassins also expanded their influence into Syria and other nearby countries. With the Seljuk Empire embroiled in civil war, the Assassins took advantage of the respite to establish themselves as a stable political force in the region. They rebuilt their fortresses, opened trade relations with nearby powers, and even levied taxes on the territories under their control. After two decades of relative calm, Hasan attempted to heal the wounds between the Assassins and the Seljuks, but his efforts fell on deaf ears.

Hasan-i-Sabah, the father of the Assassins, died peacefully at Alamut in 1124. He was followed by a succession of leaders as the Assassins continued to expand throughout the Middle East. Outside of Alamut, the greatest center of Ismaili power was in Syria. It was there that the Assassins encountered the crusading armies of the Christian West. The relationship between the Crusaders and the Syrian Assassins was the foundation for many of the popular myths about the sect. The sect’s early years in Syria did not go well. Caught between the rampaging Crusaders and the vengeful Seljuk Turks, the Syrian Ismailis paid a high price in both gold and blood. In their early engagements, the Crusaders conquered several Assassin strongholds and captured a high-ranking Assassin leader. They even forced the sect to pay an annual tribute. At the same time, the Seljuks began another crackdown on the sect. Thousands of Ismailis were either driven from Syria or put to the sword.

Cooperation with Crusaders

Despite these hardships, the Assassins still managed to establish a sizable presence in Syria. By the middle of the 12th century, they had taken control of a number of fortresses and created a loyal base of converts. It was also around this time that the relationship began to change between the Syrian Assassins and the Crusaders. The two groups of violent religious extremists should have been mortal enemies. Indeed, they continued to war on each other sporadically throughout the 12th and 13th centuries. Yet by the mid 12th century, there also appeared a distinct spirit of cooperation between the two groups. The main cause of this newfound friendship was the rise of Imad ed-din Zengi. Zengi controlled the Seljuk sultanate in Syria, but eventually became so powerful that he spawned his own dynasty, known as the Zengids. Zengi was a bitter foe of both the Crusaders and the Assassins, and his son Nur ad-Din would lead the Zengid dynasty to great victories against both groups. The threat posed by the Zengids led the Syrian Assassins and the Crusaders to join forces against their common enemy. One of the most famous examples of this came in 1149, when the Assassins combined with Raymond of Antioch against Nur ad-Din. This unprecedented collaboration was a failure, and both Raymond and the Assassin leader were slain.

The bizarre relationship between the Crusaders and the Assassins is perhaps best exemplified by the alternating friendship and animosity between the Syrian Assassins and the Knights Templar. Both the Knights Templar and the Assassins were legendary for their religious devotion, proclivity for violence and extreme secrecy. Although diametrically opposed in belief, the two groups were actually very similar in practice. Both adhered to a severe form of religious asceticism, both had a hierarchical command structure, and both believed that death in battle led to rewards in the afterlife.

The many similarities spawned a number of wild theories about the exact nature of the relationship between the two groups. Some historians have even suggested the Templar Rule was derived from the Assassins, and that their exposure to the sect was the reason behind the later charges of heresy against the Templars. However, not all was peaceful between the Templars and the Assassins. Three years after joining forces with Raymond of Antioch, the Assassins turned on their former allies. Assassin fidais murdered Count Raymond III of Tripoli, a prominent leader of the Crusaders. This prompted a swift, violent reprisal by the Templars. They defeated a local Assassin garrison and imposed a steep annual tribute on the sect. The notion that the devout Templars would accept tribute from infidel murderers was scandalous and would later be used to impugn them at their trials for heresy.

The Assassins Under Rashid al-Din Sinan

The Syrian branch of the sect underwent a massive transformation when Rashid al-Din Sinan became its leader in 1162. By the time of Sinan’s ascension to power, the Syrian Assassins were operating as a virtually independent entity. They received occasional instructions from Alamut, but all the essential leadership functions were carried out in Syria. Sinan is widely believed to have been the inspiration for the infamous Old Man of the Mountains depicted in The Travels of Marco Polo. He presided over the sect during an extremely dangerous period for the Ismailis. Their annual tribute to the Templars kept them safe from Crusader attack, but Nur ad-Din continued his assaults on the group. At the same time, another threat was emerging in the form of the legendary Saladin. Both Saladin and Nur ad-Din were Sunnis, and they saw the austere Shiite beliefs of the Assassins as heresy. As such, both leaders thought little of slaughtering Ismailis wherever they found them. The Assassins were caught between three hostile enemies.

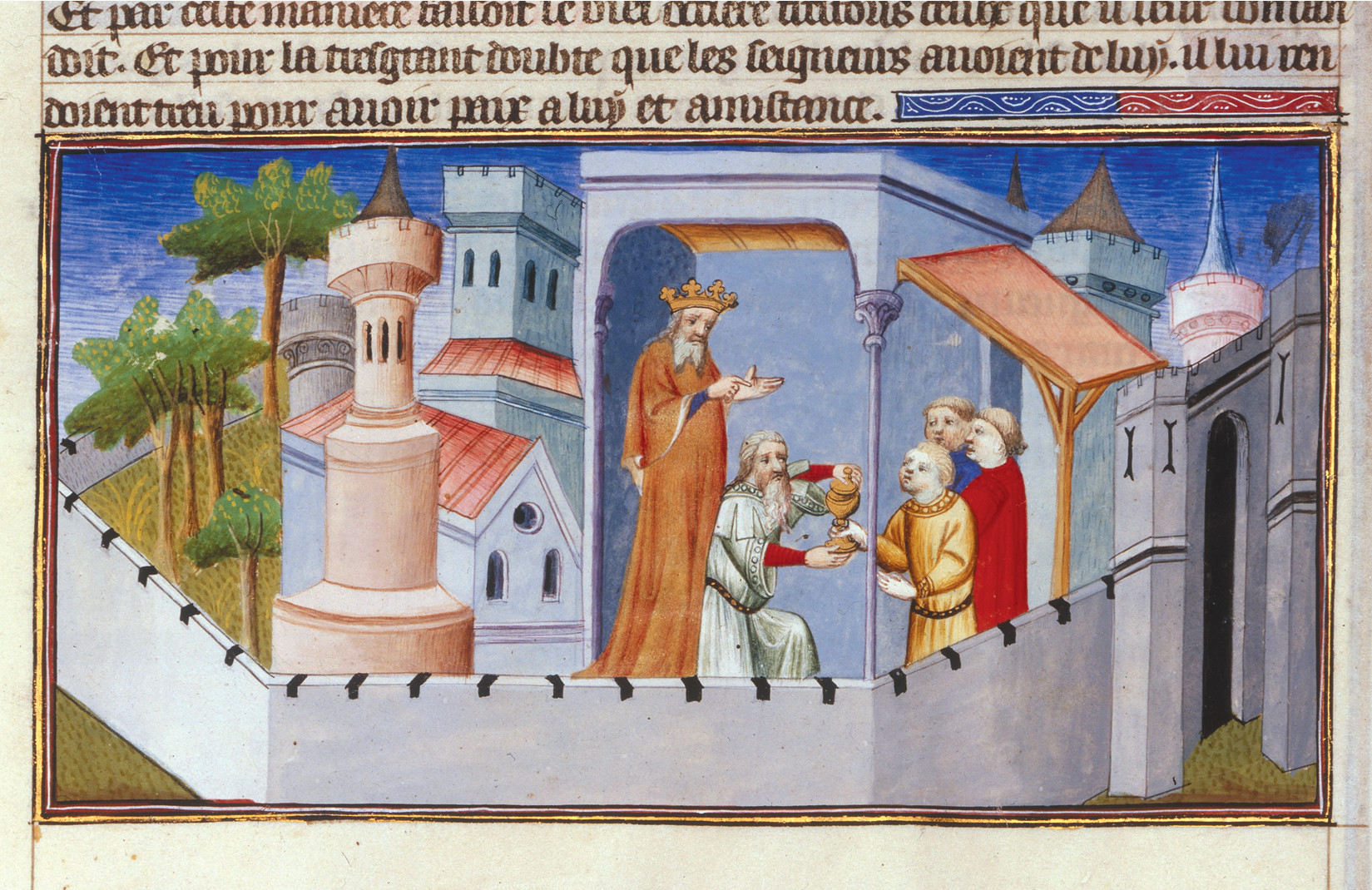

In 1173, Sinan, alarmed by the growing power of Saladin, took steps to reinforce his tentative peace with the Crusaders. What happened next has been the subject of debate for over 800 years. Some sources, including the renowned William of Tyre, believed that Sinan sent emissaries to King Amalric I of Jerusalem to propose an alliance. Sinan even offered to convert to Christianity as a sign of their newfound cooperation. A key condition of this alliance was the end of the Assassins’ tribute payments to the Templars. Amalric accepted these terms, but the furious Templars slaughtered the Assassin envoys on their way back from Jerusalem. Other sources claimed that Sinan never sent the envoys, or else that their intent was misconstrued by William of Tyre. They also claimed that a devout Shiite like Sinan would never offer to convert to Christianity. In any event, thanks to the brutality of the Templars, no formal alliance was ever enacted between the Assassins and the Crusaders.

Attempts on Saladin’s Life

Nur ad-Din and Amalric died in 1174, leaving Saladin as the primary threat to the Assassins. Sinan sent a number of fidais to murder the Muslim leader. These fidais succeeded in injuring Saladin in 1176, but his armor saved him from a mortal wound. The fact that Saladin was wearing armor under his robes shows the effectiveness of Sinan’s terror campaign. The ability of Assassin fidais to penetrate even the most elaborate security measures was well known throughout the Middle East. It soon became standard practice for leaders opposed to the Assassins to wear armor at all times, even in private. One tale claims that Saladin became so paranoid about the Assassins that he traveled inside a large wooden box. He also reportedly slept in a high wooden tower and refused to let anyone approach him whom he did not personally know. Such precautions, if true, were clear examples of the perceived power and threat of the Assassins.

After the attempts on his life, Saladin decided to rid himself of Sinan and his followers. He led a large force into Syria in 1176 and besieged the main Ismaili fortress at Masyaf. However, once again the Assassins were miraculously saved from certain destruction. After a short siege, Saladin mysteriously abandoned his assault and left Syria. Assassin lore is filled with reasons for his abrupt departure. One story says that Sinan dispatched a fidai to Saladin’s tent. The fidai plunged a dagger into Saladin’s bed, along with a threatening note. When Saladin awoke in the morning, he was so terrified that he ordered his army to withdraw. Another story says that Sinan sent a messenger to Saladin’s court. When the messenger arrived, he asked Saladin’s two most loyal bodyguards if they would kill their master for Sinan. The bodyguards nodded yes and drew their swords. Terrified by Sinan’s influence, Saladin ordered his armies to abandon the siege of Masyaf.

The true reasons for Saladin’s actions may never be known, but the impact of his experience in Syria was readily apparent in his later policies. After the siege of Masyaf, his forces coexisted in relative peace with the Assassins. Sinan ceased his attempts to murder the Arab leader, and Saladin never again attacked an Ismaili stronghold. This truce freed both groups to resume their attacks on the Christian kingdoms. Saladin’s battles with the Crusaders and his rivalry with Richard the Lionheart have been well documented. However, the Assassins’ role in these conflicts is not as well known.

Death of Conrad de Montferrat

Sinan struck his greatest blow against the Crusaders in April 1192, when two Syrian fidais disguised as monks murdered the king of Jerusalem, Conrad de Montferrat, in Tyre. The killing of Montferrat was the most infamous of all Assassin political murders. It was recounted by Western troubadours and bards for centuries and helped shape the modern image of the Ismailis as cold-blooded killers. Yet, as with many of the sect’s murders, the role of the Assassins in Montferrat’s death remains questionable. Conrad de Montferrat and Richard the Lionheart were political rivals, and some sources claimed that it was Richard’s henchmen, not the Assassins, who actually carried out the deed and blamed it on the sect. Others claimed the Assassins were acting on behalf of Richard the Lionheart or even Saladin himself, giving credence to later rumors that the Assassins were killers for hire. The Moorish traveler Ibn Battuta passed along the rumor, writing, “When the Sultan wishes to send one of them to kill an enemy, he pays them the price of his blood. If the murderer escapes after performing his task, the money is his; if he is caught, his children get it. They use poisoned knives to strike down their appointed victims. Sometimes their plots fail, and they themselves are killed.”

War with the Mongol Horde

Sinan died a few months after the murder of Montferrat, bringing to an end a remarkable period in Assassin history. After his death, the Syrian Assassins lost much of the independence they had gained under his dynamic leadership. Saladin died in the following year, ending the brief period of truce with the Ismailis. His death plunged the region into chaos as various factions struggled to seize control of his vast empire. The Assassins were once again forced to navigate stormy political and religious seas in order to survive. Their extreme Shiite beliefs continued to alienate them from the orthodox Sunni Muslims who dominated the region.

After a series of disastrous military encounters, including several raids on Alamut itself, a new Assassin grand master named Hasan III emerged. In 1210, Hasan III decided to end the political isolation of the sect by renouncing his Shiite beliefs and embracing Sunnism. During his tenure, the library at Alamut became a renowned center of learning for Sunni scholars. The Assassins even allied themselves with various Sunni governments and fought alongside them in military engagements. Their long history as pariahs in the eyes of the Sunni establishment had finally come to an end, but the reprieve was short-lived. In 1219, a new threat emerged that would soon eclipse all others—the Mongols had invaded the Middle East.

Hasan III, realizing the danger posed by the Mongols, sent emissaries to treat with Genghis Khan. This resulted in a period of truce between the Mongols and the Assassins. However, Hasan died in 1221, and with him ended the Assassins’ acceptance of Sunni beliefs. His son Mohammed III returned the sect to its Shiite roots. This shift could not have happened at a worse time. The Assassins became isolated from their former Sunni allies just as the Mongols descended upon the region. The Khwarazmian Empire in modern Uzbekistan was the first to fall to the Mongol hordes. As the Mongols conquered more territory in the Middle East, conflict with the Assassins became inevitable.

Over the next 25 years, the Great Khan and his descendants swept through modern-day Iran. The Assassins became so desperate that they put aside old animosities in an effort to forge an alliance against the Mongols. They even sent ambassadors to Europe in the vain hope that the Christian monarchs would join them against the pagan invaders. However, the European leaders, many of whom believed that the Mongol Khan was the mythical Christian king Prester John, were already attempting to forge an alliance of their own with the Mongols. Without outside assistance, the Assassins had little chance of surviving the onslaught of the Golden Horde.

The final act in the history of the Assassins begins in 1252 with the rise to power of Mangu Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan. One of Mangu’s first official acts was to charge his brother Huelgu with destroying the Assassins once and for all. The reasons for Mangu’s hostility against the Assassins are not entirely clear. One story claims that a Muslim official complained to the Great Khan about having to wear armor under his robes to protect against Assassin attacks. Ismaili lore claims that it was Mangu who did the complaining, responding to multiple Assassin attempts on his life. However, if these attempts on the life of Mangu Khan took place, they only succeeded in provoking his rage. One by one, the Assassins’ strongholds fell to the Mongols. In 1256, Huelgu’s soldiers razed Alamut to the ground. Even its prized library was burned, destroying much of the recorded history of the Assassins. The last grand master of the sect, Mohammed III’s son Khurshah, was taken to the Great Khan’s court in chains and beaten to death.

Scattered Survivors

The Syrian branch of the Assassins survived the initial Mongol onslaught. In 1260, they allied with the Mamelukes and helped to drive the Mongols out of Syria. However, without the power and influence of Alamut, the isolated Assassins had little chance of survival. Their Mameluke allies soon turned on them and conquered the last remaining Ismaili strongholds in Syria, ending the main period of Assassin history.

Although they had been destroyed as a functioning power in the Middle East, scattered groups of Ismailis still survived. Some groups remained under Mameluke control, where they degenerated into killers-for-hire for the Mameluke sultans. Others blended into the broader Islamic community while still maintaining their Ismaili heritage. The descendants of these groups have survived into the modern day. The leader of the modern Nizari Ismailis, the Aga Khan, is a direct descendant of Khurshah, the last Assassin grand master.

Precursors to Modern Terrorism?

The reemergence of Islamic extremism has once again brought the Assassins into the spotlight. They have been widely denounced in the media as the first Islamic terrorists and the spiritual forebears of such modern terrorist groups as Al-Qaeda. While much of this is political rhetoric, there are some similarities between the Assassins and today’s Islamic extremist groups. Like modern terrorists, the Assassins sought to instill fear and uncertainty in their enemies. They made frequent use of suicide attacks and believed that their actions would earn them rewards in the afterlife. They also employed sleeper agents who would penetrate enemy groups and wait for months or even years before striking their target. In addition, they were not afraid to shed the blood of fellow Muslims in order to advance their cause.

There are, however, significant differences between the Ismailis and modern extremists. Unlike the terrorists of today, the Assassins limited their targets to military and political leaders. There are no records of their engaging in the indiscriminate killing of civilians. Also, while the Assassins used terror tactics, the method in which they employed them was far different. While modern extremists seek to terrorize civilian populations, the Assassins sought to terrorize their leaders. They believed that one well-placed dagger could succeed where an entire army could not. In today’s world, with the threat of biological and nuclear terrorist attacks looming over entire civilian populations, the targeted killings of the Assassins seem almost quaint by comparison.

Is “radical” not a modern term for military orders of their time? Calling men such, who were subject to the instability of their region, is interesting.