By Don Hollway

When John Sassamon’s murdered body floated up under the ice of Assawompsett Pond, Plymouth Colony, in January 1675, few Puritan homesteaders could have foretold it would lead to the bloodiest war, per capita, in American history. Sassamon, a full-blooded Massachusett Indian, had been Christian, Harvard educated, and sympathetic to the colonists. He had informed Plymouth’s Governor Josiah Winslow that the chief of the Wampanoag tribe, Metacomet (known to the English as King Philip) planned an uprising. When an autopsy revealed Sassamon’s neck had been broken and another Indian testified to seeing three of Philip’s men kill him, the English tried and executed them. The Wampanoags, whose charity had enabled the Pilgrims to survive their first winter in America, declared war on their descendants.

At Sakonnet, on the southeastern shore of Narragansett Bay, former constable, juryman, and magistrate Benjamin Church was busy carving a farm out of the wilderness. “I was the first Englishman that built upon that neck, which was full of Indians,” Church recalled of his experience clearing and plowing, raising a house and fences, and putting in horses and cattle. These efforts required the “uttermost caution to be used to keep myself free from offending my Indian neighbors,” he wrote.

Born in Plymouth in 1639, Church was of that first generation of Americans who grew up alongside Indian tribes. “He … gained a good acquaintance with the natives,” wrote his son Thomas, who transcribed his father’s memoirs. Church earned their trust and was held in great esteem by them.

This was despite the fact that Church’s father had been a sergeant in the 1630s Pequot War, when the Puritans slaughtered almost the entire tribe and sold the survivors into slavery, horrifying even their own Indian allies. Church’s knowledge of Indian ways would make him their most terrible enemy.

Fifty years of European diseases had culled New England’s native population to approximately 20,000. The population of the United Colonies of New England (Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven) outnumbered them three to one, but Indian warriors outnumbered Puritan soldiers. By uniting the tribes, Philip might conquer the Puritans. He sent a number of envoys from his village at Mount Hope to that of Church’s neighbor, Awashonks, queen of the Sakonnet tribe. If she did not join his rebellion, they said, Wampanoag warriors would kill English cattle and burn their cabins. That, she told Church, “would provoke the English to fall upon her, whom they would no doubt suppose the author of the mischief,” he wrote.

Awashonks invited Church to meet the Wampanoags. He recalled “their faces painted and their hair trimmed up in comb-fashion, with their powder horns and shot-bags at their backs, which, among that nation, is the posture and figure of preparedness for war.” Church advised her in front of them to “knock those six Mount-hopes on the head and shelter herself under the protection of the English,” according to his son. Furthermore, he called the Wampanoags to their faces “bloody wretches … yet, if nothing but war would satisfy them, he believed he should be a sharp thorn in their sides.”

As a Puritan, Church might be guilty of the sin of pride, but he can be remembered for living up to his word. Seeking to thwart Philip’s recruitment campaign, he rode to Pocasset to meet another Indian queen, Weetamoo, widow of Philip’s brother. No friend of the English (she would be the villainess of colonist Mary Rowlandson’s famous story of captivity during the war), Weetamoo advised Church that her Pocasset warriors had already joined the hostiles. In late June 1675, a scuffle resulting in the murder of a Wampanoag incited Philip’s braves to attack Swansea, Massachusetts, killing nine colonists. The war was on.

In Europe the 17th century was an age of massive armies and months long sieges of walled cities; cuirassiers, pikes, and matchlock muskets were still in use. In this manner Plymouth and Massachusetts sent an army of 350 to relieve Swansea, thrust down the Mount Hope peninsula, bring the hostiles to battle, and end the war, all in a matter of a few days. Set-piece battles, however, were not the Indian style of warfare. The woodland tribes preferred stealth, raids, and ambushes.

“I was spirited for that work,” wrote Church. He and a small band of frontiersmen and friendly Indians ranged ahead of the colonial expedition, which was so slow on the march that Church recalled he and the rangers paused to kill a deer, “flayed, roasted, and ate most of him before the army came up with them.” Bottled inside the fort at Swansea, the English suffered sentries shot off the walls by Indian snipers in the surrounding woods. Two men sent out to a well were found later with their fingers and feet cut off and their heads skinned. When the army sallied out in force it ran into a fusillade, Indians firing from cover. Several men were wounded, one mortally, and the English withdrew into the fort. “The Lord have mercy on us if such a handful of Indians shall thus dare such an army!” wrote Church.

that inspired future generations of U.S. Army rangers.

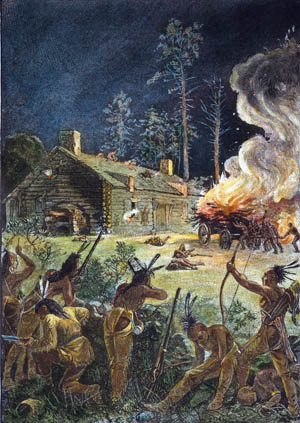

With hostiles rampaging up and down the bay, burning houses and barns, slaughtering cattle, and killing every settler they could catch, the colonial expedition finally ventured out to sweep the peninsula clear. They found only abandoned villages with English heads stuck on poles. “We shall never be able to obtain our end in this way, for they fly before us, from one swamp to another,” wrote Captain James Cudworth.

Philip had no need to hold ground in the European fashion. “Some, and not a few, pleased themselves with the fancy of a great conquest,” Church recalled of the army halting to build another fort. His son wrote that he “looked upon it, and talk of it, with contempt and urged hard the pursuing of the enemy … to kill Philip, which would, in his opinion, be more probable to keep possession of the neck than to tarry to build a fort.”

Leaving the army to it, in early July Church took three dozen rangers back to Pocasset. They soon came across a fresh native trail. He and 20 men chased two hostiles inland only to run into an immense volley of musketry. “The hill seemed to move, being covered with Indians, with their bright guns glittering in the sun and running in a circumference with a design to surround [the English],” wrote Church. Caught with their backs to the bay, for six hours he and his rangers stood off Indian attacks. Near dusk, running low on ammunition, they waved down Captain Roger Goulding’s sloop on the water. He sent a canoe to take them off two at a time and “got all safe aboard after six hours’ engagement with 300 Indians, whose number we were told afterwards by some of themselves,” wrote Church,

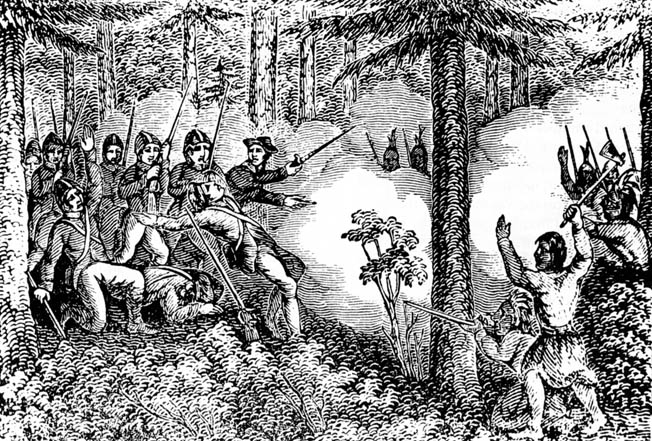

Guided by Alderman, a deserter from Weetamoo’s camp, the English returned in force, and on July 19 pursued her and Philip into the Pocasset swamp, seven miles of cedar bog and brambles. “How dangerous it is to fight in such dismal Woods,” wrote Boston clergyman William Hubbard, who likened the experience to “fighting with a wild Beast in his Den.”

In that tangle European formations and tactics were worse than useless. “The Indians always took care in their marches and fights not to come too thick together,” wrote Church. “But the English always kept in a heap together … it was as easy to hit them as to hit a house.”

“The captain of the Forlorn [advance guard] was shot down dead; three more were then killed or died that night, and five or six more hideously wounded,” recalled Cudworth. “Philip’s place of residence was about half a mile off; which we could make no discovery of, because the day was spent, and we having dead men and wounded men to draw off.” The English were “commanded back by their chieftain after they were come within hearing of the cries of [the enemy’s] women and children, and so ended that exploit,” wrote Church.

Philip escaped north to join the Nipmuc tribe. Weetamoo went south to the Narragansetts. “And now another fort was built at Pocasset,” Church wrote, “and the remainder of the summer was improved in providing for the forts and forces there maintained, while our enemies were fled some hundreds of miles into the country, near as far as Albany.”

From beyond English reach, Philip solidified his alliances. His brother-in-law Tispaquin burned Middleboro, and his war chief Totoson burned some 30 homes at Old Dartmouth. The Nipmucs besieged Brookfield for three days, causing such destruction that the town would be abandoned for 20 years.

Not all tribes sided with Philip, though. On August 1, a combined force of more than 250 Mohegans and English caught him in Nipsachuck Swamp, killing a third of his force, including four war chiefs. Philip escaped, but plainly it took an Indian to catch an Indian.

To settle with the Narragansetts, the United Colonies assembled a 1,000-man army, the largest in their history, under Governor Edward Winslow. Offered command of a company, Church declined. He preferred small unit tactics, such as sweeping ahead for prisoners. “Being brisk blades,” he recalled of his rangers, “they readily complied.” When the army arrived, Church delivered 18 captives; one, facing the noose, agreed to lead the English to the native camp, in the Great Swamp north of Worden’s Pond.

The swamp normally served as an expansive moat, but this was the depths of the so-called Little Ice Age. That bitterly cold December it was frozen solid. Through a rising blizzard the English marched over the ice and to their astonishment found the Narragansetts behind a stockade built in the European manner, enclosing some four to five acres and 500 wigwams.

Winslow’s assault was not well executed. “The best and forwardest of his army that hazarded their lives to enter the fort were shot in their backs and killed by them that lay behind,” wrote Church. They gained entry, but the battle was still raging inside when Church and 30 men pursued escaping natives across the swamp, only to dodge an incoming relief force twice their number. As the hostiles were about to retake the fort, the rangers “gave them such a round volley and unexpected clap on their backs,” Church remembered, “that they who escaped with their lives were so surprised that they scampered.”

Inside, the fort was full of blowing snow and powder smoke, flashing tomahawks and flying musket balls. Church was shot three times, “one in his thigh,” wrote his son, “which was near half of it cut off as [the bullet] glanced on the joint of the hip bone.” Unable to dislodge the defenders, Winslow gave orders to burn the fort with everything and everyone in it. Church pleaded that it was full of “baskets and tubs of grain and other provisions sufficient to supply the whole army … and every wounded man might have a good warm house to lodge in.”

Winslow would not hear of it. “And burning up all the houses and provisions in the fort,” Church recalled, “the army returned the same night in the storm and cold.” The colonists lost 70 killed, including seven company commanders, and 150 wounded, the Narragansetts, up to 150 warriors, but as many as 1,000 women and children. The survivors, who were mostly able-bodied braves, were driven firmly into the arms of Philip.

While Church recuperated at home, the hostiles ravaged the frontier in the spring of 1676. Philip assaulted Sudbury, with 500 warriors, chased a relief column onto a hilltop, set it afire, and killed 72. In early May Tispaquin sacked Bridgewater. Farther south, 1,500 Narragansetts laid waste to Rehoboth and Providence. Eventually, the rebel tribes would number approximately 8,000 warriors; of 94 New England towns, 52 would be attacked, 25 sacked, and 17 burned to the ground. “God give greater wisdom to our Rulers or put in into the King’s heart to rule and relieve us, these colonies will soon be ruined,” wrote Boston merchant Richard Wharton.

Reconsidering Church’s tactics of using Indians to fight Indians, Puritan leaders recalled him to service. He agreed on the condition that, as he put it, he would “not lie in any town or garrison with them, but would lie in the woods as the enemy did.”

“God pleased to show us the vanity of our military skills, in managing our arms, in the European mode,” wrote Puritan missionary John Eliot. “Now we are pleased to learn the skulking way of war.”

Church heard that his old neighbor Queen Awashonks desired peace. “It had ever been in his thoughts since the war broke out,” his son wrote, “that if he could discourse [with] the Sagkonate [sic] Indians, he could draw them off from Philip, and employ them against him.” She consented to a meeting, and Church convinced her to change sides. “We’ll fight for you and will help you to Philip’s head before Indian corn be ripe,” her war chief told him.

“I am glad of the success [of] Benjamin Church that it is the good fruit of the coming in of Indians to us, those that come in are conquered and help to conquer others,” wrote Puritan minister Thomas Walley,

Given command of 200 men, mostly Sakonnets, loyal Wampanoags and, as Church recalled, “English not exceeding the number of 60,” he pursued the war in the native fashion. “When he wanted some intelligence of [the hostiles’] kenneling places,” his son wrote, “he would march to some place likely to meet with some travellers or ramblers, and, scattering his company, would lie close, and seldom lay above a day or two, at the most, before some of them would fall into his hands, whom he would compel to inform where their company was. And so, by his method of secret and sudden surprises, he took great numbers of them prisoner.”

The rangers were soon hot on Philip’s trail. On the morning of August 1, they got a shot at him from across the Taunton River. They missed, but in the pursuit captured a number of Wampanoag women and children, including the chief’s wife and nine-year-old son. “You have made Philip ready to die, for you have made him as poor and miserable as he used to make the English, for you have now killed or taken all his relations,” the Wampanoag prisoners told Church.

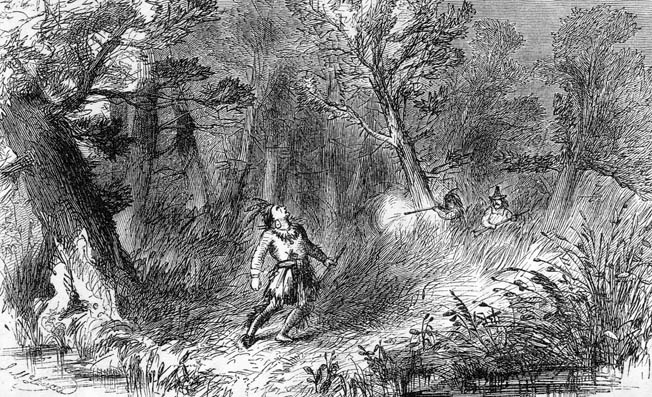

Church, however, was after more than women and children. At one point he was almost killed in hand-to-hand combat with Totoson himself. A volley of ranger fire drove the war chief off him. And on August 10, Captain Goulding brought news that a Wampanoag, whose brother Philip had killed for advising surrender, had deserted to the English. He revealed that the beleaguered, disheartened chieftain had gone home to Mount Hope, ground Church knew well.

That night the rangers and Sakonnets crept into the swamp on their bellies and surrounded Philip’s camp, awaiting first light. However, one of the hostiles, coming out to relieve himself, stumbled into Goulding, who shot him. In the ensuing firefight the war chief Annawon shouted for his men to make a stand, but Philip darted into the swamp. He ran into one of Church’s rangers and the turncoat Alderman, who had loaded his musket with two balls and put them through the chief’s heart. When the fight was over (Annawon having escaped), Church announced Philip’s death, recalling, “The whole army gave three loud huzzahs.”

Church ordered the body dragged from the muck and, in accordance with English law regarding traitors (as they considered Philip to be), he was quartered and decapitated. His parts were hung in trees, and his head was mounted on a post in Plymouth as a warning. Alderman kept his hand in a bottle of rum as a trophy.

With Philip dead the war devolved to mop-up operations. Weetamoo had drowned on August 6, trying to escape across the Taunton River. Church, with 20 Indians and five rangers, on August 28 climbed down a cliff face to surprise Annawon in his camp. The war chief presented Philip’s wampum belts and blanket to Church as trophies and marched off into captivity.

By September the rangers had captured or killed most of Totoson’s family; harried literally to death, the chieftain’s surviving son, eight years old, sickened and passed away. Totoson’s “heart became as a stone within him,” Church wrote, “and he died.” That same month they captured the family of Tispaquin, who surrendered on Church’s assurance that all their lives would be spared. Church planned to recruit the chieftains to help fight rebel tribes in Maine, but Plymouth authorities overruled him. Church never forgot finding “the heads of Annawon [and] Tispaquin, cut off, which were the last of Philip’s friends.” Tispaquin’s wife (Philip’s sister) and her children were sold into slavery along with some 1,000 Indian captives. Besides 3,000 native dead, 2,000 more fled to the interior. Up to 800 English died, which was not a large number on the scale of later wars, but in those days amounted to one in 16 men of fighting age, making King Philip’s War the costliest in American history.

In later years Church would be called back into service against the French and Indians in King William’s War and Queen Anne’s War. He led several campaigns to Maine and Nova Scotia. But he was much less nimble at that point in his life than he had been in his prime. What is more, he was operating in unknown country against well-supplied, unfamiliar foes. For those reasons, he was not nearly as successful as he had once been.

It is for his exploits in King Philip’s War that Church is revered as America’s first army ranger. Church told his men that it was necessary to “make a business of the war as the enemy did.” The tactics he adopted from Native Americans would serve his nation well 100 year later against the mother country in the American Revolution.

Was Captain Benjamin Church looked upon as a hero, or someone to emulate, to the men in the American Revolution?