By Don Haines

When twin brothers Roy and Ray Stevens of Bedford, Virginia, joined Company A, First Battalion, 116th Infantry of the 29th Infantry Division in 1938, they could not know that their decision would completely destroy their dream of one day owning a farm together.

Joining the hometown National Guard unit simply meant they would be receiving $30 per month from the U.S. government for playing soldier one night a week and two weeks every summer. Times were hard in the small farming community of Bedford, population 3,000, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal had not yet lifted them out of the Great Depression. It was possible that they could be called to active duty, but they did not think much about it. Besides, if that happened at least they would go together, which is exactly what happened on February 18, 1941, as the Bedford Boys found themselves on a train headed for Fort Meade, Maryland.

The Blue and Gray Division

The 29th was activated initially for 12 months, but Captain Taylor Fellers, commanding officer of Company A, knew the 12-month period was not set in stone. The world was an increasingly dangerous place, and he thought the Bedford Boys had best be ready for anything. He was determined that Company A would be the equal of any, and he was equally determined that his boys not be ridiculed by the Regular Army guys who generally looked down their noses at National Guardsmen, not seeing them as real soldiers.

Patriotism played a part in Ray Nance joining the guard in 1933, but the tobacco farmer admits that $30 a month was also an enticement. Today, he is quick to say, “That was cash money.” Nance had been sent to Richmond for officer training and was a second lieutenant when Company A was activated. He knew all the Bedford Boys and felt keenly his responsibility to them. The 29th was known as the Blue and Gray Division, composed of men from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, and soon after his arrival at Fort Meade, Nance would have men he did not know assigned to his platoon. He was determined that these new men would blend well, and he took a personal interest in them also. Nance knew that Taylor Fellers was very strict, and he was equally determined not to let him down.

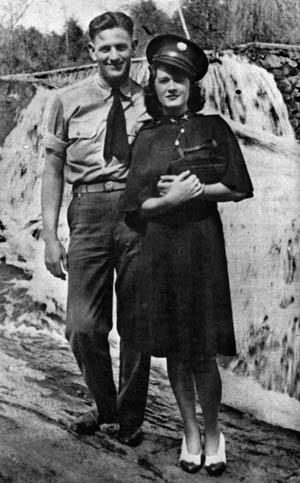

Master Sergeant John Wilkes, a big bear of a man, had proven himself an able soldier and rose quickly to company first sergeant. Wilkes demanded instant obedience and tolerated no slackers. But underneath, his young wife Bettie knew, he was sensitive and passionate. During his time stateside Bettie vowed to be with John as much as possible, a vow she kept, even traveling to Florida with other wives when the 29th was on maneuvers.

Earl Newcomb had learned to cook in a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp, so when he joined Company A in 1934 it seemed a natural transition to mess sergeant. Earl had made a vow, too. Get hot food to the soldiers of Company A whenever possible.

Allen Huddleston had been a soda jerk at one of two Bedford drug stores before joining Company A, just before they left for Fort Meade. “I knew the draft was coming, so I thought if I was going to war, I’d rather go with people I knew.”

“Whip ’em Good and Still be Home for Christmas”

At Fort Meade the Bedford Boys got a taste of what real soldiering was all about. They could soon strip their M1 Garand rifles blindfolded, and those who did not know soon learned about military etiquette or else they would be facing an Article 15, two hours of extra duty. They went on maneuvers twice, to North Carolina and Florida, where they used new radios and motorized vehicles while learning how to attack an enemy. Also at Fort Meade they learned about the advantages of central heating and running water, something most Bedford Boys had never had.

While the longest pass was two days, and Bedford was seven hours away, the boys would find a way to get there and spend some time with family, wives, and girlfriends. If they could not get home, the home folks, especially wives, would find a way to get to them.

By the summer of 1941, boredom began to settle in and grousing began. If there was no war, why did they have to be away from home? What was this Army stuff all about anyway? Come December 7, 1941, they would find out.

On that day, the 29th was in North Carolina, alternately cursing the ice and then the mud. Roy Stevens remembered how Pearl Harbor changed attitudes. “I didn’t even know where Pearl Harbor was, but I was mad. We’d slug back a beer and vow to whip ‘em good and still be home for Christmas.”

On that day, the 12-month enlistments became for the duration.

For the next 10 months the Bedford Boys and their comrades in the 29th trained, and at day’s end the conversation would always get around to what part they would play in this war. Not everyone was so eager. Sergeant Earl Parker had just found out his wife was pregnant with their first child. Parker was in no hurry to leave the United States.

An old axiom says that it takes the Army a while to move, but then it moves fast. In September 1942, the 29th found itself on the way to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. Now they knew they were on the way to Europe. While they wanted to slap the Japs, the Germans would have to do. Now the Bedford Boys wondered—how long?

Security was tight at Camp Kilmer, and try as they might the Bedford wives who wanted one last glimpse of their husbands found it very difficult. Somehow, Ray Stevens wrangled a pass to Washington, D.C., to visit his buddy’s sister. It was here that Ray for the first time declared that if he went to war he would not come back.

Come September 26, 1942, the men of the 29th were bound for Europe either aboard the Queen Mary or the Queen Elizabeth, luxury liners in civilian life but now pressed into service as military transports. They were amazed at the Spartan-like existence on these once opulent vessels, but, of course, they were carrying 7,000 men each plus crew.

The Curacoa Incident

Company A did not even reach England before the men got a taste of what it was like to see death up close.

The Queen Mary was under orders to stop for nothing and could not pick up survivors when she collided with one of the escort ships, the light cruiser HMS Curacoa, splitting her completely in two. Allen Huddleston remembered the horror. “I was lying on my bunk when I felt a slight thud. I looked out a porthole, just in time to see half a ship sinking. We didn’t even slow down.”

The men of the 29th were shocked to see hundreds of sailors drowning with no effort to rescue them. The Curacoa incident was hushed up. Officers and men were told to say nothing, and they obeyed.

Training the 29th Division in England

The 29th Division arrived in England on a cold, rainy day and reached quarters at Tidworth Barracks on October 4, 1942. It was a freezing place heated by two pot-bellied stoves that were extinguished at lights out. Their straw mattresses soon produced a scabies epidemic. After they finished scratching, Company A began 20 months of extensive training, a record unmatched by any other infantry unit.

At this time the 29th commander was Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow, a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute who knew the West Pointers back in Washington had many doubts about the mostly National Guard soldiers in his command. Gerow was adamant about his boys measuring up, and those who could not would be reassigned.

Taylor Fellers understood what Gerow was trying to do: weed out the guys who could not hack it. Lugging around a 100-pound barracks bag was too much for some, not to mention running 100 yards in combat boots in 12 seconds. Nor could they do 35 push-ups, 10 chin-ups, sprint through an obstacle course, then follow that with deadly accurate fire from a .45-caliber automatic, an M1 rifle, or a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle). They were not less brave, just less physically able. But Roy Stevens points out, “Some were transferred because of exceptional stamina, to Ranger and Airborne units, and some were sent to Officer Candidate School.”

The winter of 1942-1943 was the coldest on record in England, but the training never slackened. Twenty-five-mile marches in large overcoats were routine. “You’d have icicles on the outside and be sweating like crazy on the inside,” remembered one veteran.

The following spring the Bedford Boys were camping out on the hated moors. “You couldn’t stay dry,” said Allen Huddleston. “One time we had to set up our pup tents in a driving rain. Captain Fellers kicked a bunch of them down because they were not in perfect alignment. Guys were still in them.”

Roy Stevens knew Taylor Fellers better than anyone, especially the good time guy under the tough exterior. “Sometimes, on a long march I’d go up and walk beside him and start talking about the good days back home. I could really get him going. Of course this was always out of earshot.”

Even men training for the greatest military venture of all time—and by now there was plenty of talk about what they were being trained for—had to have some play time, and nobody can play like an American GI. They would visit the pub, imbibe too much, be carried to their barracks, and wake up the next morning with a terrible hangover. They vowed never to be so foolish again; however, it was a vow that would last only until the next pub visit.

A GI Song About the Hated English Moors

After a year and a half in England, the men of the 29th were anxious to get on with the job and go home. Once a traveling evangelist had a huge sign on his tent that read: Where will you spend eternity! A GI had scrawled underneath it: In England!

On occasion, too, a GI could wax poetic. About the hated moors they sang:

“I want to go again to the moors,

To follow their winding trails,

To stand again on their lonely slopes

In the cold and the wind and the gales.

Oh, I’ll go out on the moors again,

But mind me and mark me well,

I’ll carry enough explosives,

To blow the place to hell!”

Not all of the 29th’s soldiers were anxious to leave England. There had been some transfers in from the 1st Division who had experienced combat in North Africa. They had had a taste of battle and were not eager to repeat the experience. Bedford Boy Earl Parker, who had just become the father of a beautiful baby girl named Danny, declared he would gladly stay in England if it kept him from assaulting a beach.

Charles Gerhardt Takes Charge

In July 1943, a spit-and-polish West Pointer named Charles H. Gerhardt replaced Gerow as commander of the 29th. Along with his fearsome reputation came the information that he had little regard for National Guardsmen. He then shocked everyone by granting three-day passes. It was the lull before the storm.

Gerhardt had waited 20 years for this opportunity, and he was not going to blow it. The honeymoon lasted a few weeks, and then Uncle Charley began to crack the whip. He announced that everyone, enlisted and officer alike, would henceforth shave clean every day, in cold water if necessary. All vehicles would be polished and as spotless as uniforms. And—Uncle Charley’s biggest hang-up—chin straps would be fastened at all times. He also had a problem with familiarity. If someone got too close, he would bark, “That’s far enough.”

Gerhardt was hated by many, but he did not care. He had already been informed that the 29th would spearhead the greatest land invasion in history, and he would not fail. It was this attitude that undoubtedly brought victory but would identify Uncle Charley as the general with three divisions, one in the field, one in the hospital, and one in the cemetery.

To give his men the feeling that they were special, he came up with an inspiring battle cry, “Twenty Nine, Let’s Go!” Before World War II was over, other units who had tired of Gerhardt’s battle cry would reply, “Twenty Nine Go Ahead!”

“We’ll All be Killed, Ray”

In September 1943, Taylor Fellers told Ray Nance that Company A would probably be chosen as part of a spearhead that would assault the coast of France. Everything was hush-hush, but most caught on as soon as they began training to land on heavily defended beaches. The troops got a little nervous when everyone from Uncle Charley on down had to take swimming lessons, but not everyone learned how to swim.

The closer Fellers got to D-Day, the less confident he became. He listened with doubting ears as the planners said the landing would be a snap. Heavy bombers would take out the enemy pillboxes and in so doing would create ready-made foxholes on the beach. Demolition experts would destroy all of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s carefully placed mines and other defenses. The battleship USS Texas would obliterate whatever the bombers missed, and Sherman tanks adorned with special flotation devices would hit the beach with the infantry and give covering fire.

Fellers listened and doubted even more. It would take a minor miracle for everything to go as planned. At one meeting, though only a captain, he spoke up. “Sir, I could take one BAR and hold that beach.” He got no reply. As he and Ray Nance left the meeting, Fellers said, “We’ll all be killed, Ray.”

Destination: Omaha Beach

The 116th Infantry Regiment, of which Company A was a part, would be assaulting a beach code-named Omaha. The troops were already being referred to as the suicide wave.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, had originally scheduled Overlord for June 5, but bad weather postponed the landing until June 6, 1944. The weather was better, but there was considerable cloud cover and the English Channel was choppy.

Fellers’s opinion was shared by a number of other soldiers. Some higher ranking officers believed the landing should be at night, which would provide an element of surprise. One officer who had served in the Pacific even questioned the landing craft to be used. The LCAs (landing craft assault) would come to a stop when they hit the beach. Landing craft with treads, which would continue as they hit land, would be better and give more protection. He was essentially told to mind his own business. The first wave would hit the beach at 6:30 am.

As D-Day approached, the already anxious men of Company A had their anxiety increased when Fellers came down with a bad sinus infection and was hospitalized. However, when they lined up to board the transport SS Empire Javelin, Fellers was there. “I trained with you, and I’ve come to die with you if that’s what it takes.”

Roy Stevens remembered, “It lifted our spirits to have our leader back.”

Charles Gerhardt was standing on the dock as the men of the 29th boarded. “Are you ready, men?”

A Bedford Boy named Bedford Hoback, who was on the same LCA as his brother Raymond, said: “Yes sir, we’re sure ready.”

The transport moved into the English Channel, and Roy and Ray Stevens stood at the rail with Earl Parker, who took a photo of his daughter out of his pocket and said, “If I could see her just once, I wouldn’t mind dying.”

“Battles Never Go as Planned”

Twelve miles from Omaha Beach, the troops stepped off the transport and into their LCAs. Roy was on a separate craft from Ray and still bothered by Ray’s feeling of impending death. Roy had refused to shake his brother’s hand on the ship because he knew Ray saw it as their final contact. “I’ll shake your hand later, up at the crossroads above the beach sometime later this morning.”

Ray offered his hand again, and again Roy refused. As he sat hunkered down in LCA 911, Roy looked over at 20-year-old VMI graduate, Lieutenant Edward Gearing, a born leader, so young, yet so competent.

In LCA 910, English Sub-Lieutenant Jimmy Green stood beside Taylor Fellers. Green could not help but feel that the 60 pounds each 29th Division soldier was carrying would be too much weight in deep water. Suddenly, Green winced as the stern of 910 collided with 911. There did not appear to be any damage, but a short time later his stoker said 910 was taking on water. Green decided to go ahead, depending on the pumps to keep them afloat. His orders were to get these men to Omaha by 6:30 am.

As they headed inland they did not know the Allied bombers had missed most of their targets. Because of cloud cover, the pilots had dropped their bombs far inland, killing some French civilians and cows, but few Germans. There would be no ready-made foxholes.

To make matters worse, many of the DD (duplex drive) Sherman tanks, their flotation devices inadequate in the choppy water, would flounder and sink without reaching Omaha Beach. Captain Fellers knew what this meant, but when asked by Jimmy Green if the LCAs could go in without the tanks, he replied, “Yes, we must get there on time.”

Years later Roy Stevens was asked if a kind of Murphy’s Law could be applied to D-Day. He replied, “Yes, battles never go as planned.”

Hitting Omaha Beach

At 6 am, Ray Nance, who was scheduled to land at 7:30, peered through a slot in his LCA, remembering to keep his head down. His job would be to set up a command post, so when radioman and Bedford Boy John Clifton told him the antenna was broken on the radio, Nance told him to keep it and they would repair it on the beach.

In LCA 911, Roy Stevens said a prayer for himself and his comrades, most of whom were so seasick they did not care whether they lived or died. Then, suddenly, their craft began to sink beneath them. They tried bailing with helmets but it was too little, too late, and soon everybody was in the water. Stevens could barely swim and his 60 pounds began to drag him under. Luckily, Bedford Boy Clyde Powers was a good swimmer and kept Stevens from drowning.

While bobbing in the water, they heard their radio operator yell that he was drowning. They looked around, and he was gone. Lieutenant Gearing saved a couple of men by cutting their packs off. Their situation seemed hopeless until Jimmy Green, passing them in LCA 911, told them to hang on and he would pick them up on his way back. Hearing this, Gearing told Roy Stevens he was in charge and to keep talking and make sure the men stayed together.

With that, Gearing started swimming toward the beach. The men in the water said they knew Stevens would keep them alive because he was concerned about his brother. Jimmy Green kept his promise, and soon those who had survived the sinking were back aboard the Empire Javelin. They would return to England for rest and refitting and then be sent back to France.

LCA 910 touched down on time 30 yards from shore. Taylor Fellers thanked Jimmy Green for getting them in. Fellers had asked Green to give him some covering fire when they got in the water, saying, “My men are National Guard troops and have never been in combat.”

As much as Green wanted to honor the request, he could not. The water was just too rough. Green watched as Fellers and his men, who included brothers Raymond and Bedford Hoback, walked through the water with their weapons held high. Upon reaching the beach, they lay prone 50 yards from their objective, the D-1 Vierville draw. As they stood to run to their objective, the Germans opened up. Within seconds, Taylor Fellers, husband, son, brother and leader of men, along with the 29 others in his LCA lay dead.

A Heaven Sent Corpsman

The LCA carrying Master Sergeant John Wilkes experienced the same withering fire, but he and some of his men miraculously made it to the beach. The last they saw of him, Wilkes was firing his M1 at a German emplacement. He would be found later, a bullet through his forehead. Bettie’s sensitive, passionate man would not be coming home. Nor would Earl Parker, the Bedford Boy who said he would gladly die if he could see his daughter just one time. His body was never found.

Lieutenant Ray Nance remembered that when his LCA got to the beach the ramp would not go down. “Get it down!” he screamed, knowing the Germans would be keying on the craft. Finally, the ramp went down and Nance plowed straight ahead. When he looked back, no one was behind him. The Germans had annihilated most of his men in an instant. As he got closer to the beach he saw the body of Bedford Hoback. Then he saw the bodies of two more Bedford Boys. Nance was shocked by the carnage. He had trained these good men and seen them grow as soldiers.

“I felt responsible for them, every last one,” he recalled. “They were the finest soldiers I ever saw.”

Then Nance collected himself. He had a job to do. He started to crawl toward a cliff, the only available cover. Suddenly, a machine gun bullet tore away part of his heel and blood spurted. It was then that Nance had the first of two D-Day experiences he would never forget.

“Just as I was about to give up hope I looked up in the sky, which had a rosy appearance,” he recalled. “A warm feeling came over me, and I knew I was going to live.

“An immaculately dressed Navy corpsman leaned over me and began dressing my wound,” Nance said of his second experience. “He gave me a shot of morphine, said this is worse than Salerno, good luck to you.”

Then he was gone.

When Ray Nance told this story, people told him he was hallucinating. No one could look that good after coming in on an LCA. But Nance had his bandaged foot to prove his story. Today he feels that the Navy corpsman was heaven sent.

Later, a Sergeant came by and carried Nance to an aid station. “He put me down and I noticed what looked like a pie plate,” said Nance. “I started to put my hand on it. The Sergeant shouted, “Don’t touch it!” Nance had nearly put his hand on a German mine.

There was another angel of mercy on Omaha that day. His name was Cecil Breeden, Company A’s medic. He was credited with saving many lives and would continue to do so all the way to Germany. Breeden never got a scratch. Many thought the Iowan deserved the Medal of Honor.

19 Lost Bedford Boys

Roy Stevens was intent on finding his brother. The first thing he and Clyde Powers, who also had a brother in another LCA, did was visit the cemetery. Stevens walked to the part of the cemetery with graves of soldiers whose names began with S. He scraped some mud from a dog tag hanging from a cross and saw that it belonged to his twin brother, Ray. At the same time Powers found his brother, Jack.

Finally, Stevens said, “Come on Clyde, let’s get the men who did this.” As Roy Stevens left the cemetery, one thought came to mind: Why didn’t I shake his hand? As things turned, out the Powers and Stevens families would have one son return from war. The Hoback family had lost both sons.

In all, 19 Bedford Boys died on June 6, 1944. Three would be killed later. No other community in the United States suffered such a loss. Only 10 percent of Company A survived the landing without being killed or wounded. They truly were the suicide wave.

Roy Stevens vowed to kill one German for each of his buddies. On June 13, he volunteered to lead a patrol, then regretted his decision. “At that moment I looked in the bottom of my foxhole and saw the face of Jesus Christ. He said, “go ahead, you’ll come back.”

Stevens survived the patrol. “I’d come back just like he said I would. Right then and there I prayed and made a deal with God: ‘If you let me get home, I’ll be your servant.’”

Men react differently to tragedy. Clyde Powers mourned while Roy Stevens wanted revenge. He went on other dangerous patrols and even volunteered to take messages to artillery units. Word got around that he had a death wish, which led to a reprimand from his commanding officer. “You take it easy, it’s going to take all of us to win this.”

“Twin Brother Farewell”

Roy Stevens’s combat time came to an end on June 30, when an antipersonnel mine shredded him with ball bearings. While lying in sick bay, he noticed he was next to men deemed too far gone. He grabbed the smock of a passing nurse.

“I’m not here to die, I just need a little help,” Roy begged.

The nurse replied, “If you let go of me I’ll see what I can do.” Surgery saved Stevens’s life, and he was flown to a hospital in England on July 30. While in the hospital he wrote a poem about Ray and included it in a letter to his mother. He titled it “Twin Brother Farewell.”

I’ll never forget that morning,

It was the 6th of June

I said farwell to brother, didn’t think it would be so soon.

I had prayed for out future, that wonderful place called home.

But a sinner’s prayer wasn’t answered, now I’ll have to go there alone.

Oh brother, I think of you, all through the sleepless night,

Dear Lord, he took you from me, and I can’t believe it was right,

This world is so unfriendly, to kill is now a sin, to walk that long narrow road, it can’t be done without him.

Dear Mother, I know your worries, this is an awful fight,

To lose my only twin brother, and suffer the rest of my life.

Now fellows take my warning, believe it from start to end,

If you ever have a twin brother, don’t go to battle with him.

This poem now rests on the kitchen wall of Roy Stevens’s Bedford home.

Bedford Boy Allen Huddleston missed the D-Day landing due to a broken ankle suffered in training. He rejoined Company A on August 28 and recognized no one.

“My first day somebody asked me if I knew Joe Parker,” said Huddleston. “I said yes. He said, ‘Well he was killed yesterday.’”

Like the Hoback family, the Parker family lost two sons. It might be considered a stroke of luck that younger brother Billy, serving in another unit, became a POW. Perhaps it saved his life. Huddleston never saw the Company A mess sergeant, but Newcomb kept his promise to his buddies to serve hot food whenever possible.

Huddleston was wounded in the shoulder on September 30, 1944. He still remembers the cumbersome brace he wore for several months. “I asked if they could just put a cast on it, but they said they needed to know if the wound began bleeding.”

No Word of the Bedford Boys

When families back in Bedford got news of the D-Day landing, they huddled around their radios. They had no way of knowing whether their men had been involved in the landing because mail was heavily censored. However, they suspected this was the reason that Company A had been in England for such a long time.

News of the invasion filled them with renewed vigor. Wives and mothers who had rolled thousands of bandages rolled even more, filled with the hope that their sons and husbands would soon be home. They could not know that 19 of the Bedford Boys already lay in foreign graves or floated lifelessly off the coast of France.

On July 4, 1944, the Bedford Bulletin reported that Company A had been commended for its actions on D-Day, but still no news about individual Bedford boys had arrived. About this time, letters written to a number of the men came back as undeliverable.

Bettie Wilkes would be the first to get some news, a month after D-Day, and it was much less than official. She was standing on a street corner when called to by a woman across the street.

“Bettie, did you hear about John?” Then the woman crossed the street. “He was killed.”

Bettie rushed home in a state of shock. Family members tried to convince her that surely the government would have told her if anything had happened. Bettie never revealed the name of the bearer of bad tidings.

Another letter followed to the Fellers family that Taylor had been killed, but still no word came from the Army. According to Bedford resident Helen Stevens, “It was like waiting for an earthquake.”

“We Have Casualties”

On July 17, Elizabeth Teass, the 21-year-old Western Union operator at Green’s drugstore, reported for work as usual. She switched on her teletype machine and sounded a bell heard in Roanoke 25 miles away. She typed the words, GOOD MORNING. GO AHEAD. BEDFORD. Words came chattering back. GOOD MORNING. GO AHEAD. ROANOKE. WE HAVE CASUALTIES.

Teass watched as one telegram, then two, then three came through. She waited for the teletype to stop, but it did not, not for a long time. Teass was in shock. Why so many? But she knew her job. The families must be the first to know.

Today, Elizabeth Teass is somewhat embittered because some have suggested she handed out the telegrams willy-nilly for delivery. “Mr. Frank Thomas, an employee of the drug store, usually delivered telegrams in town, so he took some,” she remembered. “But some of the families lived outside town. Mr. Carder, the undertaker, delivered one of these. Sheriff Jim Marshall took one, and so did Doctor Rucker. Then Mr. Roy Israel, who operated the town taxi service, told me not to hand out any more, that he would deliver the rest. Each telegram that was delivered had to have a verification of delivery slip come back. Bedford was one quiet little town. Everyone’s heart was broken.”

Roy Stevens may have said it best. “A veil of tears hung over Bedford.”

There could not possibly be a more appropriate place for the National D-Day Memorial, which was dedicated on June 6, 2001. Of the 35 Bedford Boys who went away to war, 13 came home. Roy Stevens played an active role in the establishment of the D-Day Memorial. He returned to Omaha Beach for the 50th anniversary of the landing in 1994. He died in 2007.

Ray Nance was proud of the fact that he reestablished Company A in 1948. He thought it would be a good morale booster, and the young men of Bedford flocked to join. Company A went to war again in 2004 in Afghanistan. This time everyone came home. Ray Nance died in 2009.

Allen Huddleston is a widower and still subscribes to the magazine, The Twenty Niner. He operated a photo shop and is now a talented painter. Others give Huddleston credit for writing the inscription on a monument dedicated in the town in 1954. But he modestly says that it was a group effort.

“We Must Get There on Time”

One question that has been debated is why Company A was chosen for the first wave against Omaha Beach. General Gerhardt explained it this way when he came to Bedford to dedicate the 1954 memorial: “Why was the 116th Infantry picked for that particular job? Because they showed the characteristics necessary on that particular day. Who were these boys? The record of the 29th goes back to 1620, through the regimental history of Virginia troops, and their record has been unequaled. Those boys were the descendants of those who fought with Jackson, Lee, and Stuart.”

But perhaps there is a simpler explanation: that the commanders knew the type of soldiers they were sending would carry out their orders, no matter what; that though they feared the dragon, they would not hesitate to march into its mouth if that was their mission. Nothing typifies this better than Taylor Fellers’s reply to Jimmy Green:

“Yes, we must get there on time.”

I it would have been bypassed, the bloody Omaha beach