by John Domagalski

With bond clerk Marge Henning standing by as a witness, Colonel Frank Eldridge removed the first piece of the puzzle. For every war bond purchased, one piece was to be removed from the huge jigsaw puzzle that had been erected on the wall of the Chicago Signal Depot. Hidden below the mosaic was a painting of the warship that bore the city’s name.

The festivities on March 3, 1943, were part of “Avenge the Chicago Day,” organized in memory of the heavy cruiser that had been sunk near Guadalcanal two months earlier. It marked day 15 of a 40-day drive to sell $40 million in war bonds to be used for building a new war ship to be named after the city.

The Amassing Japanese Fleet

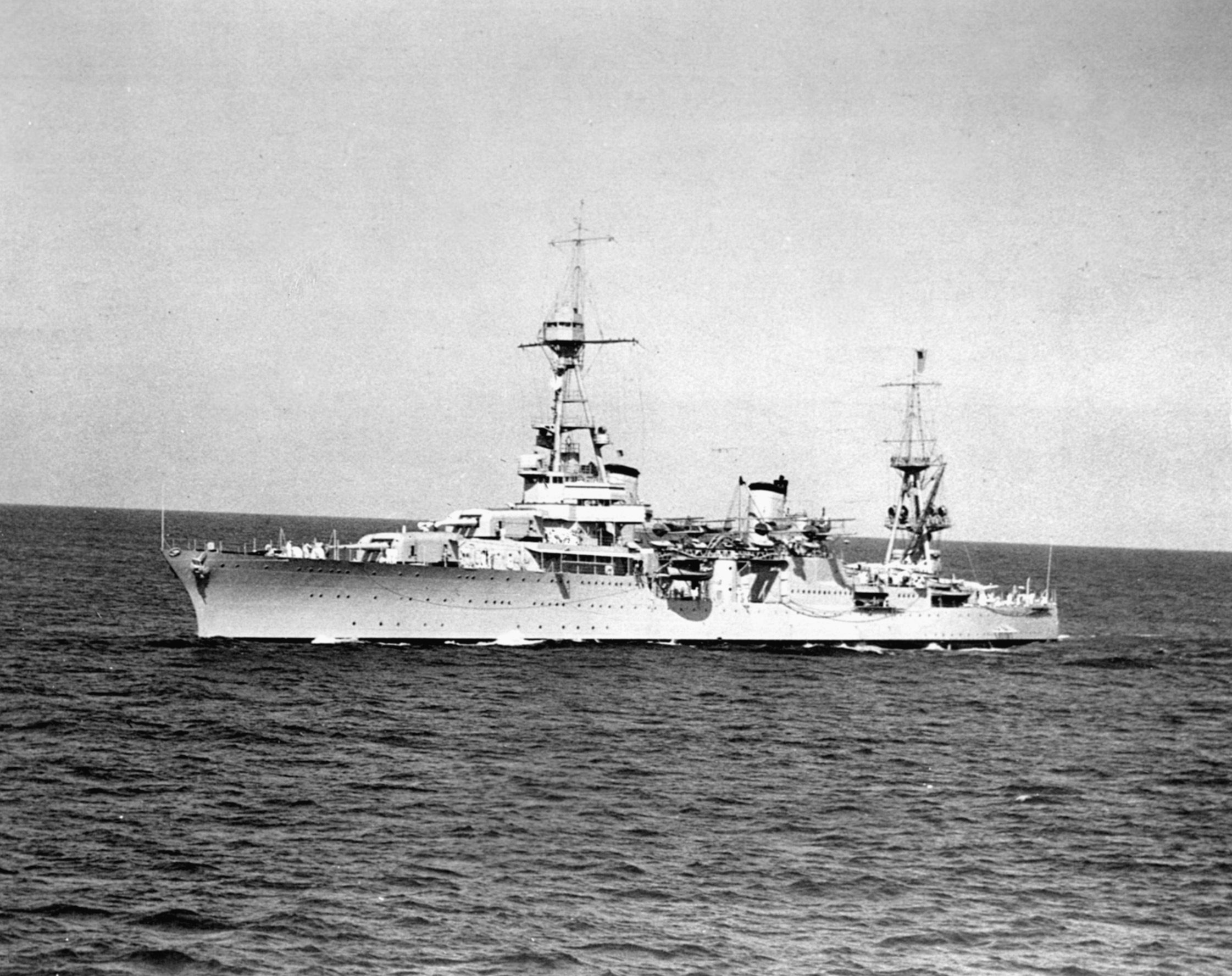

The man-o-war depicted on the Signal Depot Wall and her valiant crew left behind a record of courageous service that would long be remembered. She was launched at the Mare Island Navy Yard on April 10, 1930. The fourth ship of the Northampton class, the Chicago bore hull number CA-29. A typical inter-war American heavy cruiser, the ship displaced 9,300 tons as launched and had a peacetime crew of about 750. As built, the main armament consisted of nine 8-inch guns in three turrets and four single-mounted 5-inch guns. An assortment of 40mm and 20mm antiaircraft guns were later added as secondary armament.

The morning of December 7, 1941, found the Chicago about 420 miles southeast of Midway Island escorting the aircraft carrier USS Lexington on a mission to deliver planes to the island’s airfield. After hearing of the Pearl Harbor strike, the task force immediately began a fruitless search for the Japanese attack force.

In May 1942, the Chicago engaged Japanese aircraft during the Battle of the Coral Sea and was involved in an antisubmarine operation near Sydney, Australia. The cruiser again battled Japanese planes while covering the American invasion of Guadalcanal on August 7-8, 1942. On August 9, the Chicago was badly damaged during the Battle of Savo Island. Hit by a torpedo in the bow, the cruiser returned to the West Coast for permanent repairs. In early January 1943, the Chicago sailed out of San Francisco bound once again for the South Pacific.

January 1943 marked the fifth month of bitter island fighting on Guadalcanal. The first major American offensive in the Pacific was still not over. Although U.S. forces were in firm control of much of the island, the Japanese showed no signs of leaving. Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations, was getting impatient. “I am still unhappy about the lack of progress,” he lamented. “At present, as for some months past, it seems to me that we merely continue to ‘swap punches’ with the enemy—to our advantage for sure—but without working to any plan that is apparent here.” King wanted to secure the lower Solomons and continue on the offensive.

In late January, aerial reconnaissance reported major Japanese fleet units in the vicinity of Ontong Java Atoll to the north of Guadalcanal. Other reports indicated increased activity near the major air-sea base of Rabaul on the island of New Britain to the northwest. It appeared that a big Japanese naval operation was in the works.

Provoking the Japanese Navy

In charge of the South Pacific area since October, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey decided to act. To cover a convoy of four troop transports loaded with Marines and supplies bound for Guadalcanal, Halsey decided to deploy a vast array of sea power. A total of six task forces were deployed northeast of Australia in hopes of luring the Japanese into a major engagement. The new battleships North Carolina, Washington, and Indiana would participate in the move north, as would the carriers Saratoga and Enterprise. The carriers were the lead ships in Task Forces 11 and 16, respectively.

Traveling well behind the two forward task forces, these groups would be ready to tangle with any heavy Japanese fleet units that might venture south. All of the task force commanders were charged with the general mission of destroying any Japanese forces encountered on the move north. Leading the sortie were two task groups that started their journey on January 27. The troop convoy, built around the transports President Adams, President Hayes, President Jackson, and Crescent City, left from New Caledonia.

Designated as a close support group, Task Force 18 consisted of three heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, eight destroyers, and two escort carriers. The force, which departed from Efate in the New Hebrides, was under the command of Rear Adm. Robert C. Giffen, who had just arrived from the Atlantic on his flagship, the cruiser Wichita. A 1907 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Giffen had commanded a destroyer in World War I and served in the Atlantic during the early days of World War II. Most recently, he had commanded Task Group 34.1 during the Allied invasion of North Africa.

Giffen was ordered to rendezvous with Destroyer Squadron 21, which had been operating near Guadalcanal, and sweep to the northwest of the island while the transports unloaded. The meeting was to take place off the southwest coast of Guadalcanal at 9 pm on January 30. On January 29, Giffen received warnings of possible Japanese intentions. Specifically mentioned were several submarines thought to be operating in the area and a large number of enemy aircraft sighted around Guadalcanal. The communications also warned of a possible night air attack.

To move his task force northward at an increased speed, Giffen detached the escort carriers Chenango and Suwannee along with two destroyers at 3 pm on January 29. The carriers continued to provide fighter cover for Task Force 18 during daylight hours as they moved southeast. Freed up from the slower speed of the carriers, the remaining ships moved north at 24 knots to keep the appointed rendezvous. Task Force 18 now consisted of the heavy cruisers Wichita, Chicago, and Louisville, the light cruisers Montpelier, Cleveland, and Columbia, and six destroyers.

In accordance with his experiences in the Atlantic, Giffen was concerned about possible submarine attacks. He divided his cruisers into two columns, light cruisers on the left, and heavy cruisers on the right. The six destroyers formed a half circle in front of the two columns. This formation provided good antisubmarine screening and quick movement into surface battle positions, but it was less than ideal for protection against air attacks due to the less protected rear areas. Giffen provided no specific orders to the ships of his task force as to how to respond to an air attack.

Attacks from the Air

On the evening of January 29, Task Force 18 was zigzagging on a base course of 305 degrees traveling northwest toward the rendezvous point at 24 knots. With darkness approaching, the fighter cover had put down for the night. The force had passed north of Rennell Island and was about 35 miles from Guadalcanal. The Chicago was second behind the Wichita in the right column of heavy cruisers. Its sister ship Louisville was immediately behind.

In command of the Chicago was 52-year-old Captain Ralph Davis. The ship was darkened and conducting radar searches with all antiaircraft batteries manned. The sun had set and the task force was now moving into twilight.

At 7:10 pm, the Chicago’s CXAM radar contacted unidentified planes 25 miles to the west. The planes were making a wide circle and approaching the rear of the task force. Reports on the TBS (talk between ships) from the Wichita confirmed that they were enemy planes. Aboard his flagship, Admiral Giffen thought the radar plot looked like “a disturbed hornets’ nest.”

By 7:20 pm, the enemy planes had divided into two groups and were approaching the task force from behind the starboard beam. Such positioning silhouetted the ships against the twilight glow. The groups were closing at ranges of 10,000 yards and 17,000 yards. Captain Davis ordered his ship to general quarters. The ringing alarm sent the crew racing to battle stations.

The approaching planes were Mitsubishi G4M Type 97 bombers. Known to the Allies as a “Betty,” the twin-engine land-based bomber was capable of a remarkable range of almost 3,700 miles. Harold Beckman, a cook aboard the Chicago, saw the Japanese planes coming in for the attack from his station on the ship’s well deck. “Enemy Zero [fighter] planes came on machine gunning the decks in an endeavor to get the men from their stations. Then the torpedo planes dived at us. It was really a suicide attack. The way they came on gave them no means to turn back and some of them fell in flames on the Chicago’s port side.”

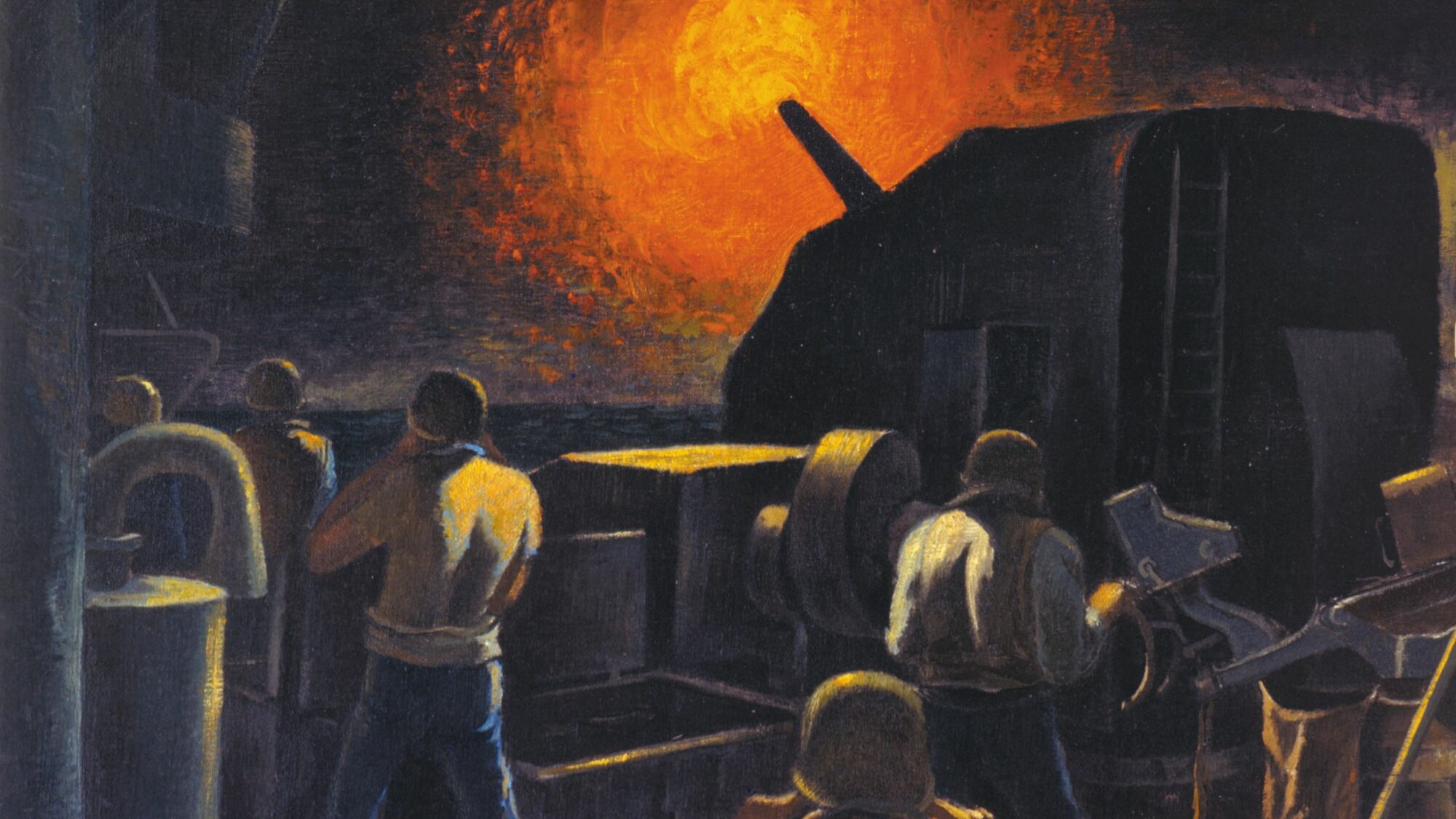

The fast moving Bettys started their torpedo runs low and fast, approaching the heavy cruiser column from the unprotected starboard stern quarter. At about 7:25 pm, the destroyer Waller, positioned immediately to the starboard of the Chicago, opened fire on the first group of approaching planes. Chicago’s starboard 5-inch and 40mm batteries soon joined in the barrage, the former under full radar control. It had been approximately 12 minutes since the initial radar contact.

The Chicago was equipped with the secret new proximity fused antiaircraft shells. Used with fragmentation shells, the fuse contained a radio transceiver that caused the shell to explode when near a target. As a result of the new weapon, a near miss was almost as good as a hit when firing at enemy planes.

Targeting the Chicago

Two bombers approached the Chicago from the after section of the starboard beam. At least one torpedo hit the water 500 or 600 yards out, but no wake was seen. Both planes passed ahead of the Chicago, apparently undamaged by the heavy barrage of antiaircraft fire. Another plane launched a torpedo in the direction of the Louisville, which avoided being hit only by making a sharp turn to port. Tracers lit up the darkening sky as all ships of the task force fired away at the attacking planes. Exploding in flames, one Betty hit the sea close behind the Chicago.

The Japanese planes moved past the cruisers and retired off the port bow of the task force. The first attack ended with no ships reporting damage. Focused on making the appointed rendezvous, Giffen continued at the same speed on the same base course and discontinued zigzagging to make up for lost time. Suddenly, flares began to appear on both sides of the task force. White parachute flares were seen dangling in the sky, while red flares glowed on the ocean surface below. Dropped by Japanese scout planes, both types served to illuminate the ships against the now dark sky. Japanese aircraft now had a beacon that would lead them directly to the American ships.

Shortly after 7:30 pm, more bombers appeared out of the eastern sky. One Betty launched a torpedo ahead of the Chicago. It passed harmlessly through the cruiser’s wake. At least one torpedo was thought to have passed near the Wichita. A second torpedo hit the Louisville but failed to detonate.

Appearing tall against the background of the flares, the right column of heavy cruisers continued to be the focus of the air attack, with more planes closing at about 7:38 pm. One bomber went down in flames directly behind the destroyer Waller. A second was hit and caught fire. It burned brightly as it passed near the Chicago, lighting up the deck with burning fuel before crashing into the sea off the port bow.

Lieutenant Edward Jarman was the Chicago’s air defense officer. He recalled the near miss. “We filled one torpedo plane so full of steel that it almost exploded on the Chicago. It missed our boat by 10 feet. It burned three or four minutes, silhouetting us for the second wave.” Fed by aviation fuel, the wreckage burned brightly, illuminating the cruiser and making it an easy target for other approaching planes. “They all concentrated on the Chicago,” Jarman said, “apparently mistaking her for a battleship.”

Two Torpedo Hits

At 7:40 pm, a torpedo hit the after engine room on the starboard side of the Chicago with a thunderous explosion. Radio technician John Erby was near where the torpedo hit. “I was in the starboard passageway when the first torpedo struck not 30 feet away from me. Not long after the torpedo hit, the communications failed and we had to leave the passageway,” he recalled. “We joined a gang trying to put out fires and we fought desperately to save the ship.” Two minutes later, a torpedo wake was sighted closing in fast. Almost immediately, a second torpedo exploded against the starboard side hitting near the No. 3 fire room and forward engine room.

As a result of the first hit, propeller shafts 1, 2, and 3 stopped immediately. Control of the ship was lost as the rudder locked at 10 degrees to the left and no longer responded to commands from the bridge. Four compartments, including the after engine room and the No. 4 fire room, were flooded. Water began to slowly enter the crew’s mess. The Chicago, now listing to starboard, began to settle by the stern. Emergency diesel generators were started to provide power for lighting, electrical fire pumps, submersible pumps, and radios.

The second torpedo hit flooded the No. 3 fire room and forward engine room. The machine shop was demolished. Several small fires broke out. The starboard list gradually increased to 11 degrees. Soon afterward, the No. 4 propeller shaft stopped, leaving the Chicago dead in the water. The Louisville turned sharply to avoid hitting her stalled sister ship before taking up position behind the Wichita.

Admiral Giffen was notified by TBS that the Chicago had been torpedoed and was disabled. Now under the cover of darkness, he took steps to help protect the remaining ships from further air attacks. Giffen changed course to 120 degrees and slowed the task force. The reduced speed made it difficult for the Japanese pilots to spot the white wakes behind the ships. Antiaircraft fire was prohibited unless directed at a definite target. Unable to get a good fix on the American ships, the remaining Japanese planes headed home.

To Save the Chicago

On the Chicago, damage control parties sprang into action immediately in a determined effort to save the ship. The crew was not only well trained but also had firsthand experience after dealing with torpedo damage at the Battle of Savo Island. As at Savo, all hands were determined to save the ship.

Fires and flooding were of immediate concern. Small fires in the galley and radio room II were quickly extinguished by damage control parties. Bulkheads were shored up to prevent further flooding. Albert Bartholomew, the ship’s carpenter, led a damage control party deep into the ship to close critical hatches. The party “worked like dogs to keep us afloat,” he said. “They swam 30 feet in water chin deep, dodging heavy tables and chairs as the ship rolled, to dog down hatches.”

Leaks in the laundry and ice machine rooms were quickly plugged. Flooding boundaries were established, allowing bucket brigades to begin their work. Engineers began to work on the jammed rudder, which was straightened out shortly after midnight.

The key to saving the crippled Chicago was getting her out of range of land-based Japanese bombers. Accordingly, shortly after midnight preparations were made for the Chicago to be taken under tow by the Louisville. Under the command of Captain Charles Joy, the Louisville maneuvered into position with its stern about 1,000 yards off the bow of the Chicago. After resolving some initial problems that occurred while trying to position the cruisers close together in the darkness, sailors began the arduous task of connecting the two ships with a thick steel chain.

Captain Joy later commented, “The passing of the tow was accomplished without a hitch and exactly as planned, with no injury to personnel, or damage to material.” Once attached, the Louisville moved ahead slowly at four knots, bound for Espiritu Santo. Three destroyers accompanied the connected cruisers on their slow journey south. The remaining ships of Task Force 18 headed west to screen against any possible Japanese ship movements.

Help was also on the way from other sources. Admiral Halsey ordered Task Force 16 to move toward the stricken cruiser. Under the command of Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman, the task force was about 350 miles south of the Chicago. Built around the carrier Enterprise, the force headed north at 28 knots.

Sherman was directed to provide fighter air cover over the Chicago during daylight hours. To accomplish this, he had to put the Enterprise in a precarious position. The carrier had to be close enough to the cruiser to allow for a short flight time for his fighters, yet far enough away that Japanese planes sent to attack the Chicago would not be in a position to sight the Enterprise. Additional fighter protection would be provided by the escort carriers if needed. The fleet tug Navajo and the destroyer Sands were also dispatched to assist in the rescue mission.

Meanwhile, frantic work continued aboard the Chicago. The No. 2 mess hall, after engine room, forward engine room, and machine shop were open to the sea as a result of the twisted metal from the torpedo hits. However, most of the leaks in other compartments were plugged, and great progress was being made to remove water in flooded areas.

Attention now turned to correcting the starboard list. Shortly after midnight, boiler No. 4 was restarted to provide additional power to the ship. Booster pumps were now able to correct the list by shifting fuel oil. As a precautionary move, the captain ordered that most of the life rafts and floater nets be cut loose and placed on the deck.

The prognosis for the Chicago now seemed to be improving. “We were settling fast and it looked touch and go whether we would sink. The next morning we were taking on more water than the books said we could and keep afloat,” recalled Lieutenant Jarman, “but we kept her up.” Maybe the cruiser would live to fight another day.

Spotted by the Japanese

It was just before 6 am on January 30, when four Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bombers lifted off the flight deck of the Enterprise. Disappearing into the predawn sky, their mission was to visually locate the Chicago. At 7:15 am, the damaged cruiser was sighted about 35 miles east of Rennell Island. By 8 am six Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters of Fighter Squadron 10 were on station overhead. Four other fighters circled above the Enterprise.

The tug Navajo arrived shortly after 8 am to relieve the Louisville of towing duties. In the early afternoon, Admiral Giffen signaled the Chicago to call a destroyer alongside to transfer off any unnecessary personnel at Captain Davis’s discretion. Davis signaled the Wichita back, asking if the destroyer could also transfer his wounded men to a land hospital.

Giffen replied that no destroyer could leave the task force due to the continued submarine threat. Davis decided to keep the crew aboard and prepared to defend the ship against another air attack, which seemed all but certain. Later in the day, Halsey ordered the remaining undamaged cruisers of Task Force 18 to head for port. At 3 pm, Admiral Giffen wished the Chicago good luck and headed south toward Efate.

Leaving with the cruisers was the task force’s fighter direction officer aboard the Wichita. As a result, there would be no on-site command and control for the fighters assigned to protect the Chicago. Screened by six destroyers, the cruiser continued south at four knots, under tow by the Navajo. As each hour passed, the Chicago slowly limped farther away from the danger of Japanese bombers.

The Japanese seemed determined not to let the crippled cruiser get away. At about 8:30 am, Wildcat fighters above the Enterprise chased off a Japanese spotter plane that was sighted about 20 miles west of the carrier. The plane likely reported the positions of both the carrier and the crippled cruiser.

American Aircraft Out of Position

By mid-afternoon, coastwatchers had spotted a flight of Japanese aircraft south of New Georgia heading for Rennell Island. Shortly afterward, a warning message from Guadalcanal was picked up by the Enterprise. The fighter direction team aboard the carrier quickly estimated that the bombers would be in the area at about 4 pm. The Enterprise was now about 43 miles southeast of the Chicago. Ten Wildcat fighters led by Lt. Cmdr. William Kane were on patrol above the cruiser.

At 3:40 pm, fighters over the Chicago sighted a single Japanese plane north of Rennell Island approaching at high altitude. The plane was likely a spotter, sent in advance to guide the main attack formation to the target. Kane dispatched four Wildcats to give chase. The Japanese plane turned south and headed around the eastern end of Rennell Island, putting it in a position to see both the Enterprise and the Chicago.

The Wildcats gave chase, speeding at full throttle toward the twin-engine Betty. A well- placed burst of machine-gun fire knocked out the starboard engine on the Japanese plane, which began to slow and trail smoke. Ensign Hank Ledar pulled his Wildcat in for the kill. Soon, the enemy aircraft caught fire, turned into a ball of flames, and spiraled toward the sea. The chase had carried the four fighters nearly 40 miles away from the Chicago and out of position to deal with the main enemy formation that was now approaching.

At 3:54 pm, radar aboard the Enterprise picked up an incoming flight of 12 Japanese bombers 67 miles away and bearing 300 degrees. The course had the bombers heading directly toward the Enterprise. The carrier increased speed as nearby ships closed to form a protective shield. Antiaircraft guns were aimed skyward as the radar plot showed the enemy planes moving closer at 8,000 feet with their noses low, readying for torpedo runs. Ten additional fighters prepared to take off to meet the attackers. Kane had landed to refuel, and the six fighters still over the Chicago were now under the command of Lieutenant MacGregor Kilpatrick.

The fighter direction team aboard the Enterprise directed Kilpatrick’s six fighters away from the Chicago into a position to intercept the bombers heading for the carrier. Kilpatrick and his wingman separated from the remaining four fighters as the Wildcats moved into position to meet the oncoming attackers. The Japanese bombers, then 17 miles from the carrier, suddenly made a sharp turn away from the Enterprise and headed directly for the Chicago.

“We dropped down to the attack. The Jap commander saw our Wildcat fighter planes and realized he could not get across the miles separating him from the task force, so he took what seemed to be the easy way out,” recalled Kilpatrick in a later interview. “The torpedo planes turned sharply and headed west toward the Chicago.”

Kilpatrick’s four Wildcats, which a moment earlier stood ready to intercept the incoming bombers before they reached the Enterprise, were now behind the enemy planes and giving chase. The 10 fighters that had lifted off the carrier were too far away to play a role in the impending air battle, as were fighters from the escort carriers that had separated from Task Force 18 a day earlier.

Only Kilpatrick and his wingman, Bob Porter, were in position to intercept the bombers before they reached the Chicago. Both Wildcats turned sharply and dove in for the attack, riddling two Bettys with machine-gun fire on the first pass. Kilpatrick recalled the action: “[B]efore the Japs had come completely around, two of their number were spinning down with dead pilots at the controls.” The remaining torpedo bombers pressed home the attack.

Four More Torpedo Hits

The battle that followed was a short but frenzied event that took place at high speed in close proximity to the stricken cruiser. With the CXAM radar out of commission (it had been damaged in the first torpedo attack), the incoming bombers were sighted by a lookout on the Chicago at a distance of seven miles. Eleven bombers were counted speeding in low and fast from the starboard side.

Directly between the Chicago and the approaching planes stood the destroyer La Vallette, which trained all available guns skyward and opened fire. Two minutes after the initial contact, the starboard 5-inch battery of the Chicago joined in at an initial range of 8,000 yards, firing the first of what would be 49 rounds of ammunition expended in the battle. The smaller 40mm and 20mm guns opened fire as range allowed.

The crews of both ships fought desperately to shoot down the enemy planes before they could launch their deadly torpedoes. Marine Sergeant Anthony Anderson aboard the Chicago recalled how his men kept fighting in the face of both wounds and great danger. “[Private William] Stander continued firing despite two bullets in his back until I took him out of his harness and got in myself and kept his gun firing. [Private Harold] Dixon stayed at his post until he collapsed. [Private Verona] Brown had shrapnel wound in his right leg, but he got down on one knee and kept loading.” Sustaining a bullet wound to the thigh, Brown survived and was later evacuated from the ship on a stretcher.

At least two Japanese planes fell into the water off the starboard side of the Chicago. A third Betty approached as if to crash into the cruiser. With one engine on fire, the plane sped toward the cruiser as antiaircraft gunners tried to shoot it down. The flaming plane missed the stern of the ship and hit the water off the port quarter.

By this time the four diverted fighters initially from the Enterprise caught up to the Japanese bombers. They joined Kilpatrick and Porter, following the Japanese bombers into the field of antiaircraft fire being put up by the Chicago and the La Vallette. Incredibly, not one of the Wildcats was damaged as they followed the bombers right over the Chicago, sending two more Japanese planes down in flames. The antiaircraft fire subsided as the remaining enemy aircraft passed with the Wildcat fighters in hot pursuit.

Moments after the bombers had passed, five torpedo wakes were sighted approaching the Chicago from the starboard beam. Under a tow that was making only three knots, the cruiser was in no position to take evasive action. The first torpedo hit well forward at 4:24 pm, showering the forecastle and bridge with water and debris. Only seconds later, three more torpedoes exploded in rapid succession, some hitting near the already damaged engineering and engine rooms. The fifth torpedo passed off to the stern.

Standing between the attacking bombers and the Chicago, the La Vallette was hit by a single torpedo on the port side. Twenty-two crewmen, including damage control and engineering officer Lieutenant Eli Roth, were killed in the blast. The explosion flooded the forward engine and boiler rooms almost immediately, with the water soon spreading to the after boiler room. Quick action by damage control parties managed to contain the flooding. The La Vallette survived the ordeal and was eventually towed to port. The Chicago would not be so fortunate.

The Chicago Finally Sinks

It soon became apparent that the Chicago was in serious trouble. After the torpedoes hit, the list to starboard increased at a rapid pace as water poured in. With the situation hopeless, Captain Davis gave the order to abandon ship. Life rafts were thrown overboard, with some difficulty on the port side due to the increasing list. Crewmen aboard the Navajo worked to cut the tow line.

As the crew began to leave the ship, another battle was being waged below. Crewmen in the sick bay, many wounded in the first attack, were now becoming trapped in the flooding compartment. Lieutenant Jarman commented on the bravery of the ship’s doctor, Lieutenant Everett Jones: “Dr. Jones carried out a spinal meningitis case and then tried to rescue another patient, but he couldn’t go back down because of the inrushing water.”

Jarman recalled an orderly evacuation. “We got off every survivor on rafts. We had nearly 300 recruits, but all were orderly and waited orders. There was no panic.” The Chicago rolled over to starboard and began to sink stern first with colors flying. “She laid over on her starboard side and went down fast but smooth,” Said Jarman. “She fired a five-inch salute to herself as she went down—shells exploding from the heat of the torpedo set [sic] fires.”

Erby watched the ship go down while floating in the water. “It was like watching someone I have known and loved go down under the waves. All the men floating in the water cheered.” At 4:43 pm, 19 minutes after the first torpedo hit, the bow disappeared below the surface. The proud cruiser Chicago was now only a memory.

The destroyers Waller, Edwards, and Sands joined the Navajo in rescuing the crew of the Chicago. Planes and ships continued to search the area until all survivors were believed to be recovered. Of the 1,130 officers and men aboard ship at the time of the attacks, 1,069 were rescued. In his official action report, Captain Davis praised his crew for “their excellent and fearless work in keeping the ship afloat after the first action and for their courageous and orderly conduct in abandoning ship when the ship was sinking.”

Loss of the Chicago, Victory at Guadalcanal

The Battle of Rennell Island was over. For their part, the Japanese claimed to have won a decisive victory. On February 1, Radio Tokyo reported that Japanese naval air forces had sunk three battleships and two cruisers in two days of air attacks south of Guadalcanal. The report seemed to specifically reference the attack on the Chicago, the only accurate part of the communiqué.

“A cruiser which had escaped unscathed on the previous night was also subjected to intensive torpedo attacks. After several hits had been scored on her, she sank with a loud explosion,” said the propaganda report. The U.S. Navy reported downing a total of 17 Japanese torpedo planes during the same timeframe.

With the Japanese focused on attacking and sinking the Chicago, the four American transports arrived and departed Guadalcanal without incident. As it was later learned, the Japanese fleet was preparing to cover the evacuation of Imperial troops from Guadalcanal. Japanese destroyers began to remove troops from the island during the night of February 1, a process that continued for the next seven days. On the morning of February 9, American ground forces completed their push to the western tip of the island. On the same day, their commander reported by radio, “Total and complete defeat of Japanese forces effected 1625 today.” The long and bloody struggle for Guadalcanal was over.

The loss of the Chicago can be traced to a variety of contributing factors. Chief among them is Admiral Giffen’s complete focus on making the appointed rendezvous time with the destroyers near Guadalcanal at the expense of other considerations. His inexperience with battle conditions in the Pacific led him to arrange Task Force 18 in a formation that was not suitable for air defense. A variety of problems, poor judgments, and just plain bad luck allowed Japanese bombers to press home an attack against the crippled Chicago while she was under the fighter protection of aircraft carriers. For the Japanese, sinking the Chicago was an endorsement of the new tactic of night torpedo attacks.

The new Chicago—another heavy cruiser—was launched on August 20, 1944. Sunny skies and a cool breeze greeted the crowd that had assembled along the Delaware River at the Philadelphia Navy Yard for the event. The day also marked the launching of two other navy warships—the carrier Antietam and the heavy cruiser Los Angeles. Mrs. E.J. Kelly, wife of Chicago’s mayor, followed protocol as she broke the customary bottle of champagne against the new cruiser’s hull. “In the name of the United States, I christen thee Chicago.”

In the day’s keynote address, Undersecretary of the Navy Ralph A. Bard told the crowd, “The ships we launch today have a dual mission. They are instruments of war and peace alike.” Speaking specifically about the new Chicago, he told the crowd, “But it was the second Chicago that captures our imagination.” Although seeming distant at the moment, the last battle of the previous Chicago would not soon be forgotten.

John Domagalski is a resident of the Chicago area who has devoted hours of exhaustive research to the preparation of this article.

My Dad, Emory Cornelius Russell, was stationed on the USS Chicago during WW11.

My father, chief gunners mate Ralph Smith, manned a 5 inch gun on the Chicago. He was injured at the Coral Sea battle but returned to duty. He recalled being in the water during this event, rescued and watching from the tugboat as the Chicago was finally sunk. He had been sunk on The California at Pearl Dec 7 and finished the war on USS Oakland.

My grandfather served aboard CA29 at Rennell. Similarly I served in Pacific on active duty with USN. Would love to share info/photos, maps.