By David A. Norris

Dripping wet Union soldiers stepped out of the North Anna River’s Jericho Ford on May 22, 1864, setting foot in Hanover County, Virginia. Concerned with building fires to boil their coffee, they were unaware that Confederate General Robert E. Lee observed them through a spyglass from a high vantage point. The commander of the Army of Northern Virginia was evaluating the degree to which they threatened his left flank.

Too sick to mount a horse, Lee took a carriage from his headquarters to the location. Racked with an intensifying intestinal ailment and a high temperature, he dismissed the distant Yankees from his worries. Lee believed the Army of the Potomac’s main force intended to cross the river somewhere downstream. “This is nothing but a feint,” Lee said as he dictated orders to Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, commander of the Confederate III Corps, instructing him to remain in camp.

Hill’s troops had just completed a 30-mile march from Spotsylvania and were bivouacked at Anderson’s Station. Although Hill was responsible for covering Jericho Ford, he had failed to do so. But Lee’s intuition was dulled by his illness. On the heels of the little vanguard that crossed the North Anna were four divisions of Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps.

After the enormous Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Courthouse, Union General Ulysses S. Grant could well have halted for a few weeks’ recovery from the ceaseless carnage and heavy casualties they had endured. Instead, Grant shifted to his left and sought new battlegrounds. Heartened by Grant’s determination, and on the move against Lee once again, more than one Yankee sang “Ain’t I glad I’m out of the Wilderness” as he marched.

No one from either side would regret leaving the dark and tangled woods of the Wilderness. Nor would anyone object to departing from the trampled and muddy grounds of the Mule Shoe salient near Spotsylvania Courthouse. Ten days of grinding battle from May 5 to May 15 had cost the Union 36,872 casualties. Newspaper headlines amplified the appalling losses across the North. The enlistment terms of thousands of Grant’s men would end within a few months. A great many soldiers looked forward only to escaping from the blood-soaked battlefields of Virginia and getting home. Winning a significant victory now would bolster Northern morale and ensure reenlistments as well as more new recruits.

Confederate losses at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania were fewer than Grant’s losses; however, Grant could replenish his army from the North’s greater population. The North had a steady flow of immigrants. Additionally, former slaves and freemen joined the growing Union ranks of the United States Colored Troops.

Another loss weighed very heavily on the Rebels. Maj. Gen. Phillip H. Sheridan clashed on May 12 with Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart’s cavalry at Yellow Tavern. Sheridan drove the Confederate cavalry from the field, and Stuart was mortally wounded during the battle. Stuart’s loss was a stunning blow to Southern morale, similar to the loss of Stonewall Jackson almost one year before.

Leading the way for Grant was Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps. These troops broke camp near Spotsylvania on the night of May 20. Cavalry under Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert rendezvoused with them to screen their march. Warren’s V Corps and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps moved out the next day. Wright’s VI Corps remained behind a few more hours to divert Confederate attention from the Union shift.

Lee learned of movement on Grant’s left on May 21. With the keen eye of a military engineer, Lee saw the next good line of defense was the North Anna River, less than 25 miles north of Richmond. Named for England’s Queen Anne, the North Anna was a small nonnavigable river. Because it cut deeply through steep banks, it made an excellent defensive barrier. Each of Lee’s three army corps left Spotsylvania and marched toward the North Anna.

Of Lee’s three principal officers, Lt. Gens. Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill, commanders of the Army of Northern Virginia’s II and III Corps, respectively, were worn down by poor health. His I Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson, was in good health, but he was brand new to this high level of military responsibility. Anderson replaced Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who had been severely wounded on May 6 in the Wilderness.

On May 22, Hancock’s column turned onto the Telegraph Road, which led southeast to cross the North Anna at Chesterfield Bridge (also known as the County Bridge), about half a mile upstream from the bridge of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, & Potomac Railroad. Their southbound march would take them to Hanover Junction, which was where the RF&P intersected with the Virginia Central Railroad. Their march would put them one and a half miles beyond the North Anna River and 25 miles north of Richmond

Grant halted at a plantation near the Mattaponi River that afternoon. He and some staff officers conversed with two stiffly polite secessionist ladies who lived in the house. Burnside, who was leading his IX Corps south for a rendezvous with Lee’s army, rode into the yard and joined the party on the porch. Burnside addressed one of the women, unaware that she had stayed for some time in Richmond at a house with a view of the prisoner of war camp at Belle Isle. When Burnside asked, “I don’t suppose, madame, that you ever saw so many Yankee soldiers before?” Grant and the staff officers burst out laughing when she replied, “Not at liberty, sir.”

Lee had grasped Grant’s intentions quickly enough that both Ewell’s and Anderson’s troops began filing into Hanover Junction on May 22, comfortably ahead of Hancock. Lee set up headquarters at the Miller House, just northwest of the rail junction. His soldiers entrenched to await the arrival of Grant’s army.

The 43rd North Carolina of Brig. Gen. Bryan Grimes’s brigade shambled into Hanover Junction early the next morning after an all-night march. The Tarheels had little time to rest before being put to work on a line of earthworks northwest of the junction, facing the river between the Chesterfield Bridge and the railroad bridge.

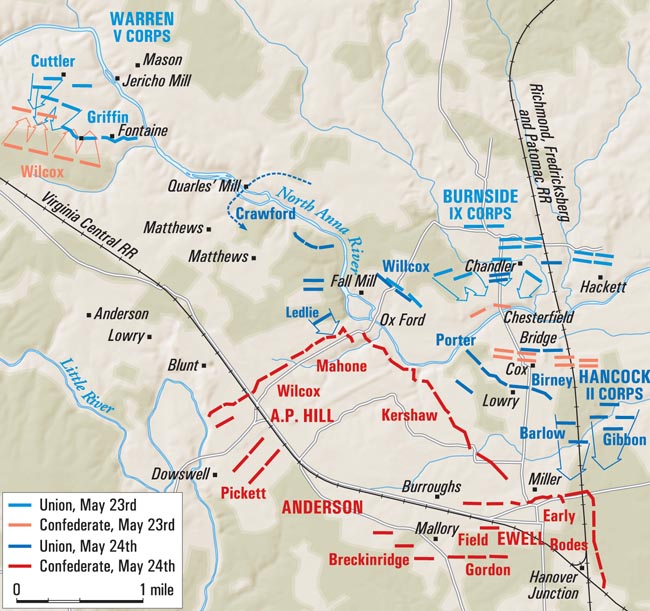

Grant approached the North Anna on May 23. Warren’s V Corps on the Union right headed toward an intended crossing at Jericho Ford. Wright’s VI Corps followed behind.

On their left, Hancock’s II Corps marched down the Telegraph Road, which crossed the North Anna at Chesterfield Bridge about a half mile west of the railroad bridge. Between Warren and Hancock, Burnside’s IX Corps marched toward Ox Ford.

Hancock’s front paralleled the stretch of the North Anna looming ahead of them. Union Army maps omitted Long Creek, a stream flowing roughly parallel with the river before turning south to empty into the North Anna between the bridges. For a time, Hancock mistakenly thought he had reached the North Anna, but he found the real river soon enough. Both bridges were intact when he arrived.

Lee did not expect a Union advance toward the Chesterfield Bridge. Only a single Confederate brigade, Colonel John W. Henagan’s South Carolinians, was north of the river. A former sheriff of Marlboro County, South Carolina, Henagan had been reelected to the state legislature the previous fall.

Henagan and the 2nd South Carolina held a small redoubt. A post-battle Union map shows it laid out like a partial pentagon, with its point aimed slightly northwest, in a line parallel with the road. The rear side was open. Built the year before to protect the North Anna bridges, the work was perched on high ground just before the terrain drops down toward the river. Its earthen walls were protected in front by deep ditches. The rest of Henagan’s brigade held lines of rifle pits on either side of the little dirt bastion. Henagan knew of Hancock’s advance, so he sent couriers requesting reinforcements or orders, but no one replied.

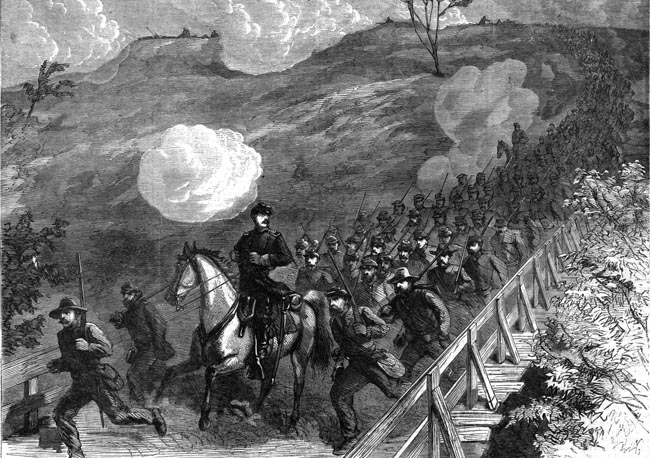

As the II Corps approached, Maj. Gen. David Birney’s 3,000-man division moved toward Henagan’s redoubt. The South Carolinians poured heavy fire into Birney’s division as they rushed across the open ground and then cascaded into the ditch fronting the walls of “Henagan’s Redoubt.” With the ditch about five feet deep, they faced a climb of 10 feet to scramble up the steep face of the redoubt.

Without scaling ladders, Birney’s men had to improvise. Sergeant William T. Lobb of the 141st Pennsylvania called out to a fellow noncommissioned officer, “Mount my shoulders!” As Lobb leaned his head and hands against the earthen walls, Sergeant John T.R. Seagraves climbed on his shoulders up to the parapet. Lobb later could not remember how many of his comrades followed Seagraves up that human ladder, but Lobb did see Seagraves holding the regimental colors atop the works.

Near Lobb, Sergeant James Anderson bore the colors of the 72nd New York (also known as the Third Excelsior Regiment) into the ditch. Several of his comrades made steps by sticking their bayonets into the bank and holding up their muskets. Anderson clambered up the makeshift stairway and waved the Union colors over the works.

Overflowing the walls, Birney’s men poured into the redoubt. As many as 200 of Henagan’s men were killed, wounded, or captured while the rest fled across the bridge. With the redoubt and the northern bridge approaches safely in Union hands, Hancock planned to cross the river the next morning.

As Hancock reached the North Anna, Warren’s corps reached the river about five miles upstream at Jericho Mill at 1:30 pm. The banks on both sides of the river there were high and steep, and the roads leading to the ford were rough. Some Union officers were disappointed that their map called the place “Jericho Bridge,” but they found only a deep ford. (The map also omitted Chesterfield Bridge, which it showed as a ford.) The Jericho crossing appeared undefended, and the lead elements of the V Corps pushed across to the south bank. The ford was more than waist-deep, but foot soldiers could wade across. It would be impossible to drag guns across, though, until a pontoon bridge was assembled.

By 4:30 pm, two of Warren’s divisions were across, a third was still in motion, and engineers had installed a 160-foot-long canvas pontoon bridge. Hill saw a chance to smash a small and isolated portion of Grant’s army, and he sent Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s division to attack Jericho Ford. Shortly thereafter, Hill sent Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division in support.

All four of Warren’s divisions were across the North Anna by late afternoon. The bluecoats halted long enough to start building fires to make coffee and cook a meal. Some of Wilcox’s men were spotted moving about in the woods beyond the campground. At first believed to be friendly troops, the Yankees quickly realized that they were Rebels. Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler’s division was ordered forward to meet them.

The orders to fall in at once came “before the men had time to drink their coffee or eat their hardtack,” wrote Orson Blair Curtis, veteran and regimental historian of the 24th Michigan of the famed Iron Brigade. “Some of the men carried their coffee pails on sticks, and others carried frying pans containing their partly cooked pork, just as they had snatched them from the fire.” Private William Rodearmel of the 150th Pennsylvania carried a fresh pot of hot coffee with him.

Driving a scattering of frightened hogs, cows, and game animals ahead of them, Wilcox’s troops crashed into Cutler’s partially deployed formation at 6 pm. Brig. Gen. Edward Thomas’s Georgians were in the lead, plowing into the Iron Brigade. Thomas was conspicuous, riding behind his men on horseback and “hallowing as if he were in a fox chase.” In the confusion, the Iron Brigade became, as one embarrassed veteran later put it, the “I Run Brigade.” They poured across the stream back to the north bank.

Rodearmel joined the refugees. A bullet pierced the coffee pot he carried, and scalding coffee gushed onto his leg. He later admitted to an officer that he rushed to the stream and waded across. Asked why he did not take the pontoon bridge, Rodearmel replied that “the bridge was too darned full of officers and doctors.”

Luckily for Warren, Wilcox’s charge began to unravel as the units drifted apart. Thomas’s brigade, with the 1st and 12th South Carolina on its right, pressed ahead into the gap left in the Union lines. The neighboring Confederate units were left far behind.

Colonel Jacob B. Sweitzer, who was until a few minutes before in the Union center, found the men of his brigade holding the Union right flank. To Sweitzer’s aid came Brig. Gen. Joseph Bartlett’s brigade. Bartlett swept toward the Confederates and smashed into the two South Carolina regiments. Isolated and far under strength, the South Carolinian regiments were overwhelmed and broke for the rear. Their brigade commander, Colonel Joseph N. Brown, was shot and captured. An Iron Brigade veteran heard a Confederate prisoner claim that the legendary brigade’s rout was really a trick to lure the Southerners into range of the Union artillery.

Brown’s repulse left Thomas’s Georgians vulnerable under heavy musket and canister fire. “The whole of Georgia broke loose and ran for dear life,” observed a soldier in the 16th North Carolina. Wilcox’s other brigades lost contact with each other and fell back under the Union attack. Heth’s division had not reached the scene before a drenching thunderstorm pounded the battlefield before dark.

After night ended the fighting, each side had suffered approximately 600 casualties. The Confederates pulled back and left Warren firmly settled on the south bank of the river. Lee’s line was now threatened by a large enemy lodgment on his left.

Lee’s illness, as well as missed opportunities and bad luck along the North Anna, provoked some of his rare but scathing bursts of temper. The next day he lashed out at his III Corps commander who was responsible for protecting his left flank. “General Hill, why did you let those people cross here?” Lee asked. “Why didn’t you throw your whole force on them and drive them back as Jackson would have done?”

On the evening of May 23, Lee shifted some of his units to meet the enemy advance. The advance works where the exhausted men of the 43rd North Carolina labored were abandoned to the brigade’s sharpshooters. The rest of the men were pulled back about one mile to the Virginia Central rail bed. By consolidating his troops, Lee ended up with a nearly ideal defensive line. Shaped like an inverted “V,” the formation is often referred to in later sources as “the hog snout line,” although this designation was not used widely, if at all, in wartime sources.

The tip of the Rebel line was anchored at Ox Ford on the south bank of the North Anna. Stretching to the left, Hill held perhaps one and a half miles of earthworks angled southwest from Ox Ford, running far enough to cover Anderson’s Station on the Virginia Central Railroad. This line ended at a winding stream called Little River, near Anderson’s Mill. The right under Anderson ran two miles southeast from the center, shielding Hanover Junction and running to meet the North Anna. Thus, Lee’s position left the Union right and left flanks several miles apart. For either Warren or Hancock to reinforce the other, troops would have to cross the North Anna twice.

Conversely, Lee could shuttle troops across the Confederate enclave by short marches through protected ground. The Rebel works were heavily fortified, so Lee could hold his front while keeping considerable numbers in reserve. With luck, his reserves would have a chance to rush out of their works to overrun one Union flank or the other and win a significant victory.

Hancock’s skirmishers on the north bank traded shots with their Confederate counterparts on the southern edge of the river until nightfall put an end to the sporadic firing. The graybacks managed to set fire during the night to the southern end of the railroad bridge. Even with the railroad bridge rendered useless, the Yankees still held the Chesterfield Bridge. Early on May 24 Hancock sent his men across the Chesterfield Bridge. He also ordered his engineers to erect a pontoon bridge a short distance upstream. Federal engineers assembled two new pontoon bridges below the ruined railroad bridge that afternoon.

Most of the Confederate infantry had dropped back from the river bank, leaving skirmishers and sharpshooters to pepper the Union foot soldiers who crossed the river. The 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, with the 20th Indiana, helped clear away Rebel skirmishers. But Maj. John Lane of Colonel Allen S. Cutts’ Artillery Battalion with six rifled guns held a bluff just downstream from Ox Ford. Lane’s pieces were within range of the Chesterfield Bridge. One shell burst killed half a dozen bluecoats on the bridge.

Three Union batteries opened fire on Lane. A Yankee shell exploded near an ammunition chest, making casualties of several gunners. Captain John T. Wingfield and Private E. Hemington prevented a larger disaster when they extinguished the cotton packing in the ammunition chest.

False reports reaching Union commanders indicated that Lee’s troops were abandoning their positions. When Burnside arrived, Grant sent his troops against the apex of the Rebel position. Grant expected the IX Corps to roll through the Rebel works at Ox Ford, and the entire Union force would unite south of the river. Colonel Benjamin Christ’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox’s division was sent forward to the river.

A stone’s throw upstream from Ox Ford, the North Anna split into two channels in which the water flowed around a wooded island. The island was not even a quarter of a mile long, but it was large enough to give cover to two of Christ’s regiments while they awaited orders to spring at the enemy works. But those orders to charge never came. While the regiments were shifted to the island, it became clear to Union officers that the Confederates were comfortably dug in. Crossing the rocky bed of the shallow river under the very noses of the Rebels would be enormously costly, if not completely impossible. Christ’s men remained in place and fired across the river at the enemy.

Next, Burnside sent Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden’s division across the river at Quarles’ Mill, about one mile above Ox Ford. Crittenden’s lead brigade, under Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie, was ordered to advance downriver and cover the rest of the division’s crossing.

“The water was so deep in places that the men had to throw their cartridge boxes across their shoulders to keep the ammunition from getting wet,” noted Lieutenant John Anderson of the 57th Massachusetts. “It was slow work floundering over the slippery rocks and through the whirling eddies…. [Once across], all were soaking wet up to their armpits.” His brigade halted for five minutes so men who crossed barefoot could put their shoes back on, and “the others to empty the water from their shoes and wring out their stockings,” he wrote.

Ledlie was supposed to watch the enemy, but not engage them. A former civil engineer, Ledlie had built a mediocre record but rose steadily in rank because of political connections, including acquaintance with Secretary of State William Seward and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Ledlie was an ineffective field commander. He drank far too much and was often absent to further his career; but his staff covered for him, and his connections made him a brigadier general in the fall of 1863.

The ambitious Ledlie thought he saw a vulnerable Rebel battery amid the enemy positions. He became eager to hurl his brigade at the enemy “before the other troops could come up, and then he would not have to make a division of the anticipated glory,” recalled Lieutenant Anderson. But even as his brigade pressed forward and pushed the Confederate skirmishers back, Ledlie sent an officer to Crittenden to ask for three regiments to follow him in support.

Crittenden could not spare any regiments yet as the rest of his men were still crossing the river. At first he bade Ledlie’s messenger to tell the general not to charge, but then Crittenden wavered and allowed Ledlie to attack if “he sees a sure thing where he could capture a battery not well supported.” Crittenden went on to warn that he had information that the enemy was in force and heavily entrenched, and an attack would likely fail.

On his way back, Ledlie’s messenger rode across high ground from where he could see a formidable trench line and dust clouds in the distance, indicating Rebel reinforcements were on their way. But he found the obviously intoxicated Ledlie in an agitated state. Ledlie already had hurled his men at the Confederates without waiting for an answer from Crittenden.

Ledlie’s brigade rushed forward as dark, menacing clouds rolled in from the west and promised a thunderstorm. Confederates stood up in their works, shouting, “Come on, Yank, come on to Richmond!”

As the Yankees drew close, the Rebel infantry opened fire, and their cannons fired canister into the enemy ranks. Dozens of Massachusetts men fell, and the flag bearer of the 57th Massachusetts was shot down. Lt. Col. Charles L. Chandler tried to take the colors, but the wounded color sergeant grasped the staff and staggered forward.

Under heavy fire, the charge halted and the men were thrown back. Chandler fell mortally wounded near the enemy works. He sent away several men who tried to help him, saying, “You can do nothing for me; save yourselves if you can.” The colonel lived for a short time after the Confederates took him prisoner. According to Anderson, Colonel Merry B. Harris of the 12th Mississippi carefully saved Chandler’s watch, his diary, and a photograph of a young woman. Harris returned Chandler’s effects to his mother via a flag of truce.

Some of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s troops shot their last bullets, but kept up their fire with anything that came to hand. Among Ledlie’s casualties were men shot with iron slugs and others skewered with flying ramrods. One soldier was shot in the leg with a four-inch piece of a broken bayonet tip. He extracted it with his own hands.

Drowning in the violence of the battle, the anticipated thunderstorm lashed the stampeding Massachusetts men as they rushed back to the river and found safety with the rest of their division. Ledlie was nowhere to be found, and he sent no orders to his officers. Far from suffering consequences for sending his men on a doomed and foolish charge while he was drunk, Ledlie was promoted to command his division early in June, upon Crittenden’s resignation. He would remain in high command until he was effectively dismissed from the army for bungling the attack at the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864.

Lieutenant George H. Mills and the 16th North Carolina were some distance to the left of Ledlie’s attack. The rainstorm did not spare them from notice of the enemy. When the rains hit, Mills wrote that he “crawled under a high piazza for protection, but had hardly gotten in a comfortable position when the first shot fired came crashing through the house above me, and I soon walked out into the rain but did not find much comfort then, for a gun fired from the opposite side of the river, enfilading our line, killed two men on the left of Company G and all was confusion for a time.”

Meanwhile, Hancock had crossed Chesterfield Bridge by early afternoon. The bridge was “constructed of plank, with posts on each side, and having a top rail of one board about six or eight inches wide,” recalled a Maine soldier.

So far Grant was stepping into the snare laid by Lee. Most of his army was on the south bank of the river. The V and VI Corps and part of the IX Corps were on Lee’s left, and the II Corps was on the right. Lee’s wedge-shaped formation neatly clove the Union force in half. Now was the time to concentrate the Confederate reserves and smash into one enemy flank or the other. Each Union flank would be hours away from reinforcements.

But by this time, Lee was incapacitated by an attack of intestinal illness. Stricken with fever, he could not rise out of his cot. Lt. Col. Charles S. Venable, Lee’s aide-de-camp, recalled his commander was in a delirious state. “We must strike them a blow—we must never let them pass us again—we must strike them a blow,” Lee shouted. But Lee was unable to lead the offensive.

Not so long before, Lee might have entrusted an able lieutenant, such as Jackson or Longstreet, with directing the complex maneuvers in his absence. But Jackson was dead and Longstreet was still convalescing. Of his three current corps commanders, Ewell and Hill also were in poor health (within a few days, Lee would replace Ewell with Maj. Gen. Jubal Early), and Anderson was new at this level of rank. The golden opportunity slipped away untaken.

Hancock’s sector was relatively quiet until about 3 pm. Elements of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s division then ran into a Confederate picket line that stretched from Ewell’s front east past the Doswell Farm.

The 19th Maine passed into a ravine carved by a small stream, climbed a steep rise, and emerged on level ground in front of the Confederate fieldworks on the edge of a wooded tract. The closest Union troops to their right were some distance away, and their left was apparently uncovered. The aide leading the regiment “seemed excited and did not know just where we were wanted,” recalled Corporal John D. Smith. Because of the rugged and wooded terrain, the Union artillery was unable to provide them any support.

One hundred yards from Ewell’s line, heavy fire cut down several of the Maine soldiers. They fell back beyond the brow of the hill as dusk fell. Smith and Lieutenant O.R. Small crept up to the top of the hill, intending to drag some of the wounded back under cover; however, the enemy fire never slackened and they were unable to help their comrades.

The 14th Connecticut of Colonel Thomas A. Smyth’s brigade was sent forward to bolster two regiments fighting as skirmishers against the Confederate right, east of Hanover Junction. “We had to go through a heavy piece of woods and it was awful,” recalled Sergeant E.H. Wade. When they came in sight of the Virginia Central Railroad, “about fifty of the enemy had piled rails up across the track, and were firing at us, but we kept pretty low,” he noted. The Rebels brought up a cannon that “threw grape and canister at us unmercifully,” but caused few casualties.

Brigadier General Stephen Ramseur’s North Carolina brigade charged out of their works at 5:30 PM, halting Smyth’s advance. To aid them, Gibbon sent Colonel John R. Brooke’s brigade to Smyth’s left. Brooke pushed close to the Confederate line by the railroad, but the same thunderstorm that interrupted the fighting at Ox Ford also struck the units engaged south of Chesterfield Bridge. As darkness fell, rather than pressing further, the Yankees held their ground and dug in for the night. By the next morning, May 25, Grant decided to break off the attacks. “To make a direct attack from either wing would cause a slaughter of our men that even success would not justify,” he informed Washington by telegraph.

Union sharpshooters remained on the island opposite the Confederate apex at Ox Ford. Picket fire sputtered along the lines during the day, joined by some cannon shots, but the low-intensity skirmishing never swelled into a battle. A minor incident, the capture of four Confederate sharpshooters, cheered up the Yankee pickets on May 25.

“These had shot a cow on our side of the river, and with matchless impudence, at a favorable moment, swam across the river to get their prize,” wrote a New York Timescorrespondent. “They were, however, seen and taken prisoners, and were marched up to headquarters in their shirts and drawers.”

Grant lingered to destroy several miles of the Virginia Central Railroad. Ties were piled to make bonfires hot enough to soften the rails. Drooping under their own weight, the rails could then be twisted beyond repair.

Grant began abandoning his lines that night and sending his units around Lee’s right. His withdrawals continued on May 26. That day Union soldiers captured a woman wearing a Confederate cavalry uniform. It was an unusual incident that several Union soldiers vividly recalled in connection with the battle.

The North Anna, Little River, and the South Anna merged into the Pamunkey River a few miles downstream. Grant saved considerable delay by crossing only the latter stream near Hanover Courthouse. By May 29 Grant’s army had assembled three miles south of the Pamunkey. Lee had no choice but to follow, leaving behind one of the best defensive positions ever held by the Army of Northern Virginia.

Compared to the appalling and endless slaughter of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, the North Anna clash paled in comparison. The Battle of North Anna seemed “a matter of brains between the generals, than brawn between the men,” recalled William Meade Dame of the Richmond Howitzers. “Some sharp fighting, on points right and left, but that was all!”

Total losses for the fighting from May 23 to May 26 are difficult to state with authority. Most casualty reports for the clashes along the North Anna are mixed with losses from Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Richmond raid and other previous and subsequent actions fought during May 1864. Most estimates fall within a range of 2,000 to 4,000 killed, wounded, or missing from each side.

Looking back years later, Private Frank Wilkinson of the 11th New York Independent Battery wrote of leaving the North Anna behind. “Before us, in the distance, rose the swells of Cold Harbor, and we marched steadily and joyfully to our doom,” wrote Wilkinson.

Catching up with Lee, the Army of the Potomac found the Confederates once again dug into a formidable defensive barrier at Cold Harbor. Grant launched a headlong attack on the Rebel lines on June 3. As many as 7,000 Union soldiers were casualties during a single, 30-minute, ill-fated action. It was the disaster Grant sought to avoid at Ox Ford on the North Anna.