By John Walker

After an almost uninterrupted, four-month-long string of Union successes beginning in early 1862, followed by the advance of a 100,000-man enemy army to the eastern outskirts of its capital at Richmond, Virginia, the Confederacy suddenly found itself in a life-or-death struggle for its very survival. By mid-June, Maj. Gen. George McClellan had deployed five Union infantry corps within six miles of the city, one north of the rain-swollen Chickahominy River and four on the south side, backed by an imposing array of big guns.

On the Confederate side, General Robert E. Lee, benefitting from McClellan’s sluggish advance up the Peninsula between the York and James Rivers, had in a matter of weeks managed to concentrate his outnumbered forces and improve the defenses around the city. Convinced that he couldn’t win a war of attrition or mount a successful defense of Richmond fighting from behind breastworks, the audacious Lee devised an elaborate plan: he would shatter the Union right flank north of the Chickahominy, threaten the Army of the Potomac’s line of supply—the Richmond and York River Railroad running back to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River—and force McClellan to evacuate his works east of the city to defend his vital supply line.

Although Lee had performed superbly in the Mexican War—he was brevetted three times and deemed by Commander-in-Chief Winfield Scott to be the “best soldier he had ever seen in the field”—Lee had yet to command a large army in the field. He had assumed his current command only days earlier, after General Joseph E. Johnston was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. Lee had inherited a loose-knit army composed of Johnston’s First Manassas veterans, the original Peninsula defensive force commanded by Maj. Gen. John Magruder, and a mixture of untested reinforcements mostly from Georgia, Virginia, and the Carolinas, which he named the Army of Northern Virginia. With his new forces, Lee moved to drive the huge Union juggernaut—the largest army ever assembled on the North American continent to that point—from in front of the Confederate capital.

George McClellan: “The Young Napoleon”

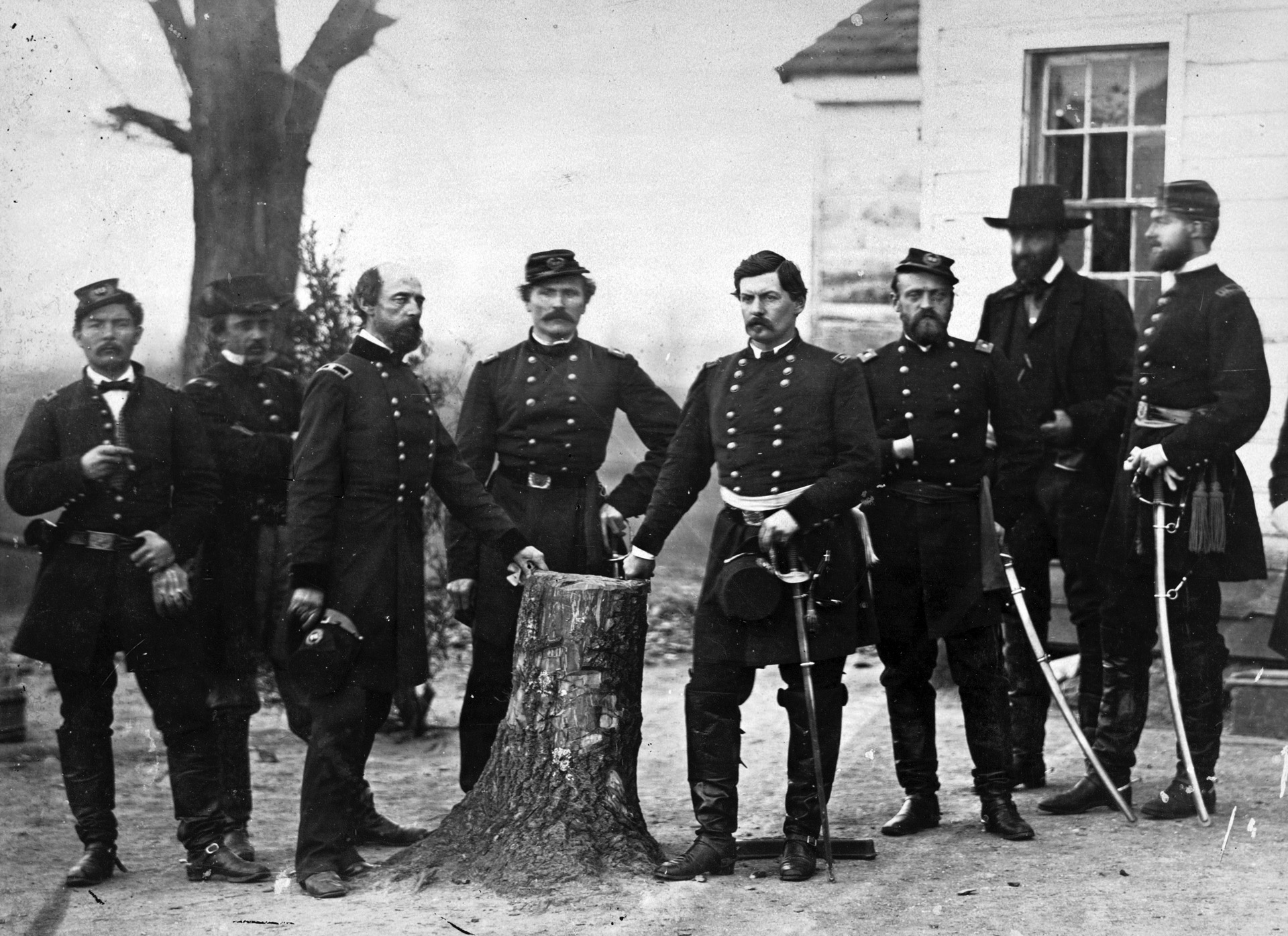

After the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run (or First Manassas, as it was known in the South), President Abraham Lincoln summoned McClellan east to take command of the Army of the Potomac. A talented, energetic officer only 34 years of age, McClellan initially enjoyed the adulation of the press and politicians who dubbed him “the young Napoleon.” He first experienced warfare in 1847 during Scott’s siege of Vera Cruz during the Mexican War. In 1855 McClellan was a member of a military commission sent to Europe by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to study military developments there and observe firsthand the fighting in the Crimea. There he gained further insights into the logistics of transporting allied forces by sea, a portent of his amphibious movement during the Peninsula campaign of 1862. After serving under incompetent political generals and witnessing the relief of his mentor, General Scott, by President James K. Polk in 1848, McClellan had developed a thorough contempt for civilian control and management of wars.

After resigning his commission in 1857 and becoming superintendent of two Midwestern railroads, McClellan first displayed the extraordinary organizational skills that eventually led to a commission to organize Ohio regiments for the Union when the Civil War erupted in 1861. In June and July of that year, McClellan led a small army to two modest victories that secured control of much of the region that soon became the Union state of West Virginia, successes that brought the call to Washington, D.C., five days after the Bull Run disaster. Few observers were aware that McClellan had been conspicuously absent from the field during much of the fighting in western Virginia, preferring instead to allow subordinates to make crucial battlefield decisions. Nevertheless, a skilled and meticulous organizer, McClellan molded the Army of the Potomac into a huge, well-disciplined fighting force, and when he finally led it on campaign, he had his soldiers’ unquestioned loyalty and affection.

The Peninsula Campaign Begins

As the autumn days slipped by and the Army of the Potomac did nothing to drive off Confederate outposts 25 miles from Washington, the honeymoon ended and McClellan’s shortcomings began to manifest themselves. He consistently overestimated the strength of enemy forces confronting him, using these flawed figures as a reason for inaction, and his lethargy, arrogance, and political convictions injected a poison into relations between the Lincoln administration and the army that persisted for almost three years. McClellan made no secret of his profound contempt for abolitionists, radical Republicans, and newspapermen who began criticizing his inactivity in the fall of 1861. Privately, he expressed his disdain for Lincoln.

Most Northerners were unaware of the growing distrust between the army commander and the administration when McClellan landed on the Peninsula and began his advance in April 1862. His amphibious turning movement gained him the strategic initiative and an almost 4-to-1 advantage over his foe at that point, yet McClellan almost immediately ceased offensive operations. Instead of smashing through thinly manned Confederate defenses at Yorktown, he instead conducted a month-long siege of the city and spent much of his time sending numerous telegrams to the War Department, complaining about his dire need for more men and matériel, wet roads, and an enemy he now numbered at 200,000 men.

Lee, meanwhile, was acting with his customary dispatch, trading space for time, improving Richmond’s defenses, concentrating his forces by recalling Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and his men back to Richmond from the Shenandoah Valley, and sending Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart on a cavalry reconnaissance on June 12 to locate McClellan’s right flank. Stuart found the enemy flank hanging in the air, not anchored on any natural barriers such as water or hills. Lee had earlier sent three full brigades to beef up Jackson’s Valley army for a possible new offensive toward Washington, but when Jackson claimed he would need even more men to mount such an offensive and hold any captured ground, Lee decided instead to bring the entire 24,000-man force back to Richmond.

A “War of Outposts”

After Seven Pines, McClellan sat passively on the outskirts of Richmond for almost a month, but by mid-June he had finally advanced his 94,000 effectives to the city’s gates. Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s V Corps, 27,000 strong, was positioned north of the Chickahominy holding high ground overlooking the small hamlet of Mechanicsville, while those of Brig. Gens. Samuel Heintzelman, Erasmus Keyes, Edwin Sumner, and William Franklin, numbering 67,000 men in all, remained south of the river. Believing his army outnumbered, McClellan’s objective now was to advance just a bit farther west, capture Old Tavern on the Nine Mile Road, entrench, and begin a classic siege. When Richmond fell, the war would be won. McClellan’s intelligence chief, Allan Pinkerton, was a competent railroad detective but an abysmal intelligence officer; in June 1862 he estimated that the Confederates in and around Richmond numbered at least 180,000—and McClellan believed him.

To get approval to carry out his bold but risky counteroffensive, Lee convinced Confederate President Jefferson Davis that McClellan would use his vast force to fight a “war of outposts,” moving inexorably from position to position while his big siege guns pounded Richmond into rubble. Lee outlined an intricate scheme that would send three-quarters of his army, under cover of darkness, north of the river, leaving 23,000 defenders to repulse McClellan’s main force south of the river should he discover what Lee was up to and mount an attack on the capital. Considering the direness of the situation—the government was preparing to flee Richmond if necessary—Lee believed the stakes were high enough to warrant the gamble.

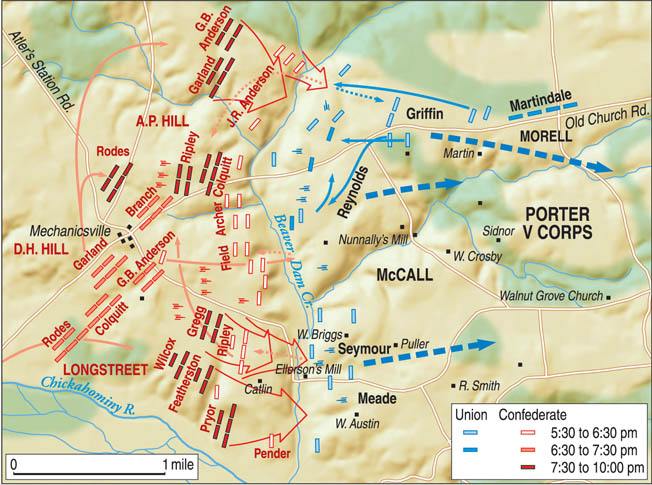

Central to Lee’s plan of operations was maneuver; Jackson would furtively return from the Valley (Lee sent orders for him to do that on June 16) and advance southeasterly around the reported enemy right flank near the headwaters of Beaver Dam Creek, his left protected by Stuart’s 2,000 troopers. Upon Jackson’s arrival in the area, he would still be at least seven miles from Lee’s main force. Therefore, early in the morning on June 26, Brig. Gen. Lawrence Branch’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s division moved up the Chickahominy to the river crossing at Half Sink, where he would establish contact with Jackson upon the latter’s arrival at the Brook Turnpike. Then, after notifying Hill of Jackson’s presence, Branch would lead his brigade down the river on a parallel route with Jackson’s men, brushing aside any threat to Jackson’s right. When Hill was certain that Branch and Jackson were on the move, he would lead his other five brigades, 11,000 strong, across the Chickahominy at Meadow Bridge, pivot, and drive eastward toward Mechanicsville, two miles away.

After Hill’s troops moved through that city, the Mechanicsville Bridge would be uncovered, allowing the divisions of Maj. Gens. James Longstreet and Daniel Harvey Hill (who would be waiting with Lee at the Mechanicsville Bridge just south of the Chickahominy) to cross and fall in behind the surging Confederate tide, Longstreet backing up Jackson and D.H. Hill supporting A.P. Hill. With vast enemy columns advancing on his front, flank, and rear, Porter would be forced to abandon his position to avoid encirclement and annihilation. Implicit in Lee’s scheme was that no major confrontation take place until Union forces east of Beaver Dam Creek had been flushed from their positions. After the carnage at Seven Pines, Lee wanted no more assaults against entrenched enemy positions.

The Risks of Lee’s Plan

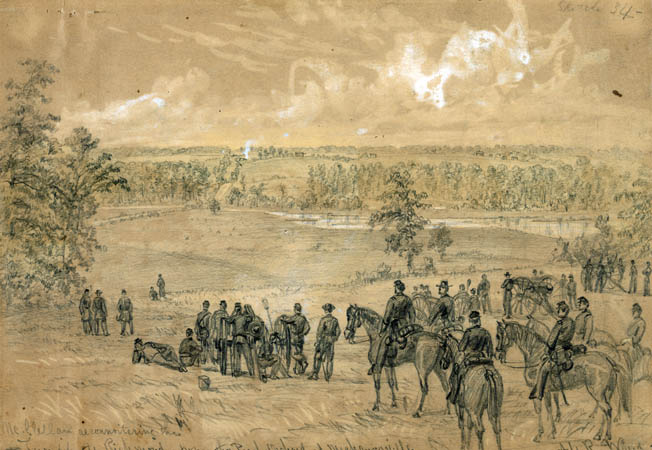

There were profound risks inherent in Lee’s plan. To begin with, Porter’s V Corps occupied a formidably strong defensive position, one that Confederate engineers had scouted weeks earlier and determined to be almost impregnable. Beaver Dam Creek, a tributary of the Chickahominy, was a swampy body of water, waist deep in places, running north-south through a wide, deep ravine a mile east of Mechanicsville. Both banks were covered by thick underbrush and trees that Porter’s men had fashioned into formidable abatis. On the west side of the creek lay an open plain swept by six Union batteries, 32 guns in all, placed in earthen parapets so as to bracket all potential approaches.

Along with the natural obstacles, McClellan had massive reserves of men available. Five regiments of riflemen of Brig. Gen. John Reynolds’s brigade of Brig. Gen. George McCall’s 8,000-man Pennsylvania Reserve Division were deployed in a roughly north-south line astride Old Church Road northeast of the village, defending 60-foot-high slopes east of Beaver Dam Creek. On their left, Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s brigade was dug in astride Cold Harbor Road, manning the high ground north and south of Ellerson’s Mill just north of Cold Harbor Road east of the creek. The grist mill’s deep pond and mill-race formed natural barriers to any troops advancing on a west-to-east line. Brig. Gen. George Meade’s brigade was deployed in reserve to their rear. Porter’s other two divisions, those of Brig. Gens. George Morell and George Sykes, almost 20,000 men, held an L-shaped line south and east of McCall’s division.

By sending six of his 10 divisions north of the Chickahominy, Lee would only have the four small divisions of Maj. Gens. John Magruder and Benjamin Huger left to defend the city. Lee was risking everything—his army, his capital, perhaps even his country’s survival. By splitting his army to gain an advantage at a critical point, he was employing a classic Napoleonic tactic. But Bonaparte himself might have balked at attacking a heavily manned defensive force astride a rain-choked river backed by giant siege guns, less than seven miles from his own country’s capital.

As usual, McClellan grossly underestimated his opponent; he told Lincoln that he actually preferred fighting Lee to Joseph E. Johnston. “Lee is cautious and weak under grave responsibility, wanting in moral firmness when pressed by heavy responsibilities,” McClellan asserted, “and is likely to be timid and irresolute in action.” Events would soon test the accuracy of his claims.

The success of Lee’s plan depended entirely on Jackson’s timely arrival. After his reinforced Valley army had begun the 100-mile trek to Richmond on June 18, first by rail, then on foot, Jackson on the night of the 22nd rode nonstop for 14 hours, arriving at the capital for an afternoon conference the next day with Lee, Longstreet, and the two Hills. Jackson’s chief-of-staff, Major Robert Dabney, was ordered to keep Jackson’s columns moving steadily forward in Jackson’s absence but proved unequal to the task. Inaccurate maps, straggling, muddy roads, and poor staff work slowed the column’s progress. After fighting six minor engagements and marching more than 500 miles in less than two months, the Valley veterans were understandably fatigued.

Jackson’s Men on the March

When the meeting ended, Jackson immediately rode back and rejoined his army, which had reached Beaver Dam Station in Hanover County, 30 miles from Beaver Dam Creek. Upon arrival Jackson discovered to his regret that only the vanguard of his army was present; the rest was strung out for 15 miles northwest on muddy roads broken by swollen streams. Physically and mentally fatigued himself, the redoubtable Jackson had only 48 hours to get his entire force to its assigned position near Richmond, 30 miles away, in time to meet Lee’s timetable. According to Lee’s General Orders No. 75, Jackson was to spend the next night at “some convenient point west of the Virginia Central Railroad,” then move at 3 am on June 26 toward his objective, Pole Green Church near Hundley’s Corner northeast of Richmond. When he passed the railroad on the morning of the 26th, Jackson was supposed to communicate his location to Branch and continue advancing. Nowhere in Lee’s somewhat ambiguous orders was there a specific mention of, or location for, an anticipated battle.

In scorching heat and adverse conditions, the June 25 march proved extremely arduous. Jackson and his men arrived west of Ashland at sundown, still six miles short of their objective, Slash Church. That night, Stuart and his 2,000 cavalrymen arrived with a three-gun battery to deploy on Jackson’s left for the next day’s march. To compensate for the six-mile shortfall, Jackson assured Lee that he would have his troops on the road by 2:30 am.

By dawn on June 26, Jackson had managed only eight hours of sleep in the previous four days, had fallen feverishly ill, and bore little resemblance to the energetic tactician of the recently concluded Valley campaign. Brig. Gen. William Whiting’s lead division, with Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Texas Brigade in the vanguard, moved out on time, but it was well after 8 am by the time Jackson’s main force—seven infantry brigades and nine artillery batteries—got underway. Food and ammunition wagons bogged down and couldn’t keep pace, and the scarcity of fresh water in the Ashland area forced soldiers to scour the countryside in search of springs or wells. Once the Confederate column was finally on the road, Jackson pushed his men forward as best he could, but one delay after another impeded his progress.

First Clash, First Blunders

Four abreast, the troops pushed forward over poor, muddy, unfamiliar roads. Their maps were woefully inadequate, and reports of enemy sightings brought the column to frequent halts. The column wound down Ashcake Road past Slash Church and reached the Virginia Central Railroad around 9 am, six hours behind schedule. Jackson dutifully informed Branch of his position by mounted courier, had a quick meal with his men, and resumed the march. The inexperienced Branch, in a costly blunder, failed to convey Jackson’s message to A.P. Hill, as ordered. Instead, upon receipt of the message, Branch and his North Carolinians, marching downriver on Jackson’s right, encountered a sizable force of Union cavalry and pickets. A vigorous skirmish ensued. The delay meant that Branch would arrive too late to take part in any action near Mechanicsville that day. Jackson’s and Ewell’s columns continued slogging ahead on parallel roads.

By 10 am, Jackson and Ewell had cleared the railroad. In the lead, Ewell turned to the right three-quarters of a mile past the tracks, pushing southward toward Shady Grove Church. Jackson continued for another mile and then turned right in the direction of Pole Green Church. Destroyed bridges, makeshift barricades, and enemy sniper fire continued to slow Jackson’s progress. Jackson sent Branch a second note at 10 am, informing him the Valley army was now two miles beyond the railroad and pressing ahead (again Branch failed to forward the message to other commanders). The two dispatches constituted the sum of all communication between Jackson and anyone in the Army of Northern Virginia that day. At 3 pm, Hood’s Texans skirmished briskly with Union cavalry near Totopotomoy Creek, then had to repair the bridge after the withdrawing Federals destroyed it.

Jackson’s Failure in Communication

Around 5 pm, having advanced 16 hard miles, Jackson arrived at his objective, Pole Green Church adjacent to Hundley’s Corner. Seeing not another soul at Hundley’s Corner, either civilian or military, Jackson sensed that something was terribly amiss. The sound of gunfire three miles to the south made it clear that an engagement of some kind was underway. Jackson’s and Ewell’s forces were still strung out along two different roads with their rear guard five miles farther behind (none of the troops in the rear element could hear the sounds of battle emanating from the south). No word from Lee had arrived. In Jackson’s mind, he had obeyed his instructions and stood ready to take part in any further advance toward Cold Harbor, which he understood to be the overall objective of Lee’s movement. His aide, Major Dabney, recalled, “Jackson appeared to me anxious and perplexed. My surmise was and is that he was every moment hoping and waiting for some definite signal from Lee, and that having reached Hundley’s Corner and still with no definite instructions, he considered the risk was too much to go further.”

Having assumed Jackson’s approach would so threaten Porter that the Union general would retire without offering battle, Lee had charted Jackson’s movement on a faulty map that placed Pole Green Church near the headwaters of Beaver Dam Creek. The church, however, was actually almost three miles north of the creek’s northern edge. At Hundley’s Corner, Jackson was in no position to turn Porter out of his works. Jackson ordered his men into bivouac in a state of semi-readiness, but failed to notify Lee or anyone else of his army’s arrival. With almost three hours of daylight remaining and the sounds of battle to the south growing more intense, Jackson’s failure to inform Lee of his presence at Hundley’s Corner was an inexplicable lapse, especially for one of the Confederacy’s most aggressive and experienced battlefield commanders.

A.P. Hill Initiates the Offensive

At 3 pm, having heard nothing from Branch or Jackson, A.P. Hill, Jackson’s old West Point classmate, ran out of patience. Richmond was in jeopardy, he wrote later, and any delay “would hazard the failure of the entire plan.” The always aggressive Hill crossed the Chickahominy and initiated Lee’s offensive on his own. Surely, Hill thought, Jackson would be present by the time he made contact. With Brig. Gen. Charles Field’s 2,000-man brigade of untested Virginians in the lead, followed in turn by those of Brig. Gens. James Archer, Joseph Anderson, Maxcy Gregg, and Dorsey Pender, Hill crossed Meadow Bridge and rapidly drove enemy pickets from his front.

The Federals began falling back toward Mechanicsville, a small crossroads cluster of houses that lay in the open surrounded by tilled fields, with Hill’s men in pursuit. Pender’s and Gregg’s brigades swung to the right to provide flank protection for Hill’s main thrust, which was now surging across the open fields toward Mechanicsville. East of the village, a six-gun Union battery opened up, exacting a considerable toll on the men of Field’s vanguard, while sharpshooters hidden behind a ridge opened fire as well.

Lee, watching from the bluffs south of the river near the Mechanicsville Bridge, saw Confederate troops advancing through the shell-swept village and observed, “Those are A.P. Hill’s men.” Lee had not intended that there be any real fighting at Mechanicsville, but here was Hill, fighting his way eastward against stronger than expected resistance. Lee quickly ordered Maj. Gens. James Longstreet and D.H. Hill to put their divisions into action.

Lee accompanied D.H. Hill’s troops as they crossed the Chickahominy and proceeded up the Mechanicsville Turnpike, with Longstreet’s division following. A.P. Hill’s troops were securing Mechanicsville when Lee arrived and learned to his dismay that he had attacked without Jackson. Lee was now in an extremely difficult situation: two-thirds of his army was north of the river, battle had been joined, Union forces were consolidating east of Mechanicsville behind Beaver Dam Creek, and Richmond was left virtually unguarded. Although he desperately wanted to avoid a clash with entrenched Federals, Lee decided there was nothing to do but continue the assault.

“As Thick as Flies on Gingerbread”

With the sun starting its descent and President Jefferson Davis and his entourage now on hand to watch the battle, A.P. Hill eagerly led three full brigades—those of Anderson, Archer, and Field—eastward, planning to strike hard at Porter’s right where he believed Jackson would momentarily appear. Anderson’s troops moved obliquely in that direction and deployed north of Old Church Road with a lone artillery battery in support. Archer’s brigade followed and took up positions astride Old Church Road on Anderson’s right. Field then posted his brigade on Archer’s right, south of Old Church Road. Gregg, Pender, and Branch remained uncommitted. As Hill’s men deployed in lines of battle and went forward, McCall’s batteries on the high ground behind Beaver Dam Creek opened fire, dividing their attention between the attacking lines of infantry and a few Confederate batteries that were soon silenced with heavy loss.

As the Confederates moved down the slope and neared the creek, McCall’s troops prepared for action. A Pennsylvania private remembered his major encouraging him and his comrades to “give them hell, or get it ourselves.” Reynolds rode along the line pointing out targets to his Pennsylvania regulars, exhorting, “Look at them, boys, in the swamp there, they are as thick as flies on gingerbread. Fire low, fire low.” His riflemen waited until the attacking line was within 100 yards before opening up. One Pennsylvania private recalled that “the enemy charged bayonets on us three times, but we cut them down. I fired until my gun got so hot that I could barely hold it in my hands. We piled them up by the hundreds, making a perfect bridge across the swamp.” McCall later described the assault: “At about 3 pm, the enemy’s lines were formed in my front and the skirmishers rapidly advanced, delivering their fire as they approached our lines. They were answered by my artillery and a rather general discharge of musketry. The Georgians rushed with headlong energy against the Second Regiment, only to be mowed down by the steady fire of that gallant regiment, whose commander soon sent to the rear some seven or eight prisoners taken in the encounter.”

“We fought under many disadvantages,” color-bearer Martin Ledbetter of the 5th Alabama Battalion recalled. “It was with great difficulty that we made our way through the entanglement of tree tops, saplings, vines, and every other conceivable obstruction, under a heavy fire.” Within an hour, hundreds of dead and wounded Confederate soldiers blanketed the terrain west of Beaver Dam Creek. As the fighting intensified along the mile-long front on both sides of Old Church Road, A.P. Hill was in the middle of it, hatless, begrimed, and oblivious to danger as he urged his men forward by personal example. He failed, however, to utilize the concentrated firepower of his division’s nine artillery batteries to contest the enemy’s guns.

The 35th Georgia Beaten Back

On the far left, despite the withering fire, some of Anderson’s 35th Georgia troops doggedly fought their way across the 12-foot-wide creek and established a beachhead of sorts, giving the men of the 2nd Pennsylvania some anxious moments. One Union officer who faced the Georgians remembered, “At one time they attacked our right and center at the same time, boldly pressing on their flags until they nearly met ours, when the fighting became of the most desperate character, the flags rising and falling as they were surged to and fro by the contending parties.” When some of Reynolds’s infantrymen ran out of ammunition, McCall sent forward two fresh regiments, the 4th Michigan and 14th New York of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s brigade. Meade brought up his four regiments into line as well.

Under infantry fire and enemy cannon firing double-shotted canister into their ranks at close range, the men of the 35th Georgia were hard pressed to hold their small piece of captured ground. Men of the 14th and 49th Georgia Regiments struggled mightily to come up in support of their comrades but were driven back with appalling losses. Without reinforcements and ammunition resupply, the survivors of the 35th Georgia later fell back across the creek under cover of darkness. On their right, the men of Archer’s and Field’s brigades, loading and firing as they advanced, also suffered terribly under the withering storm of shot and shell. Neither brigade came close to making a dent in the Union line.

“A More Hopeless Charge Was Never Entered Upon”

With three of A.P. Hill’s brigades stalled in front of the Union center and right and still no sign of Jackson, Lee decided a little after 6 pm to send another of Hill’s brigades to test the Federal left near Ellerson’s Mill. The assignment fell to Pender’s brigade, supported by a brigade of D.H. Hill’s division that had arrived on the field, commanded by Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley. By the time the divisions of D.H. Hill and Longstreet arrived, there was too much confusion and too little daylight remaining for Lee to effectively deploy and utilize them. Pender, one of the Confederacy’s most promising young officers—he was awarded a battlefield promotion to brigadier by Davis for his actions at Seven Pines—led his exposed units across the broad plateau and down the slope toward the creek. As his four North Carolina regiments and a battalion each of Virginians and Arkansans neared Ellerson’s Mill, they felt the sting of more than a dozen Union cannons and supporting infantry fire. A lone Virginia battery boldly came forward and was shattered, losing 42 of 92 men. Of the suicidal advance, Confederate Colonel Porter Alexander wrote, “A more hopeless charge was never entered upon.”

When Ripley came up, he sent his 2nd Arkansas Battalion ahead as skirmishers in Pender’s front, directly into the face of enemy defenders entrenched above Ellerson’s Mill. Two of his regiments, the 44th Georgia and 1st North Carolina, attacked on Pender’s right, while the 48th Georgia and 3rd North Carolina advanced on the left. McCall later wrote of the failed Confederate assault, “After a time, a heavy column was launched down the road to Ellerson’s Mill, where a determined attack was made. I had already sent Easton’s battery to Gen. Seymour, and I now moved the Seventh Regiment down to the extreme left, apprehending that the enemy might attempt to turn that flank by crossing the stream below the mill. Here, however, the Reserves maintained their position and sustained their character for steadiness in splendid style, never losing a foot of ground during a severe struggle with some of the best troops of the enemy, fighting under the direction of their most distinguished general. For hour after hour the battle was hotly contested, and the rapid fire of our artillery, dealing death to an awful extent, was unintermitted.”

Limping back from the creek under ruinous fire, the walking wounded brought news of the attack’s failure. The always caustic D.H. Hill said later, “The result was, as might have been foreseen, a bloody and disastrous repulse.” The 44th Georgia made it to the creek’s western bank and fought bravely for almost two hours, finally running out of ammunition and losing 361 men killed or wounded of the regiment’s 514 members. The 1st North Carolina lost 133, including its colonel, lieutenant colonel, major, six captains, and 10 lieutenants. Of the 14,000 Union soldiers engaged at Beaver Dam Creek, only 361 became casualties; the Confederates suffered 1,484 casualties. Ripley’s brigade suffered the worst, losing a staggering 575 men killed, wounded, or missing, about 60 percent of its strength.

Around sunset, Griffin’s brigade arrived on the field and took up a supporting position to Reynolds’s rear. Porter wisely extended his right flank, dispatching Brig. Gen. John Martindale’s brigade to a point behind Reynolds’s position, where he could guard against any enemy approach over the road from Hanover Court House. There, Martindale skirmished briefly with some of Jackson’s advanced pickets. Nightfall brought an end to the infantry fighting, although artillery and sniper fire continued for several hours.

The Battle of Mechanicsville: The Worst Blunder Since Ball’s Bluff

In their first major encounter, Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia had suffered a severe repulse, Lee managing to get less than a fourth of his available troops into action and then only in costly, piecemeal frontal assaults against entrenched enemy positions. Mechanicsville was the worst fiasco committed by either side since Ball’s Bluff back in October 1861, this time with the lopsided casualty figures reversed. McClellan wired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that evening: “Victory today complete and against great odds. I almost begin to think we are invincible.”

As night fell on June 26, the capture of Richmond was unquestionably within McClellan’s reach. Porter’s reinforced V Corps, now more than 30,000 strong, held near-impregnable positions north of the Chickahominy, backed by concentrated artillery batteries. McClellan commanded 67,000 fresh troops south of the river opposite 23,000 Confederates, many of them green reinforcements, while Lee’s bloodied forces north of the river were scattered and disjointed. There had been no word from Jackson since morning and no one knew his whereabouts. McClellan had two golden opportunities: he could exploit the victory by heavily reinforcing Porter north of the river, go on the offensive there, and destroy the enemy’s army. Or, as several of his subordinates implored him to do, McClellan could instruct Porter to hold the river crossings while he himself attacked south of the river, with almost a 3-to-1 numerical superiority, and captured the enemy’s capital.

Instead, McClellan did neither. After another day of combat, the bloodbath at Gaines’ Mill—Lee’s only tactical victory of the Seven Days, won at horrendous cost—McClellan abandoned all thought of making a stand or going on the offensive. Incredibly, the Young Napoleon wired Washington on June 28 that he was under attack by superior numbers on both sides of the Chickahominy. “I have lost this battle because my force was too small,” he wired Stanton. “The government must not and cannot hold me responsible for the result. If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army.” An astounded colonel in the telegraph office deleted the final two sentences before transmitting the dispatch to Stanton.

McClellan ordered Porter to protect the river crossings while he prepared for a “change of base,” a euphemism for retreat, to the James River. The Army of the Potomac conducted a skillful fighting retreat that severely punished the attackers, especially at Malvern Hill on July 1, but despite continued pleas by his subordinates to use that victory as a springboard for a counteroffensive, McClellan continued the retreat. By abandoning the York and Richmond Railroad, he effectively lost the ability to mount and maintain a siege of Richmond and surrendered the initiative to Lee. By July 2, the bloodied but still combat effective Army of the Potomac was more than 20 miles from Richmond, at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. Within weeks, McClellan would evacuate the Peninsula.

The Seven Days replaced Southern despair with renewed hope. “The almost funereal pall which has hung around our country since the fall of Fort Donelson, seems at last to be passing away,” declared the Richmond Examiner on July 4. “From out of gloom and disaster of the past, the martial spirit has emerged, and the superior skill and valor of our men over our brutal foe is incontestably established.” Somehow, McClellan had managed to turn victory into defeat. It would not be the last time he accomplished that questionable feat.

What Magazine and Issue was this in? If it is not available digitally I plan on buying a print copy.

Thanks

You can purchase that issue here:

https://portal.publishersserviceassociates.com/carts/war/index.php?route=product/product&path=40&product_id=95

Ok Thanks

This should have a strategic map. It is difficult to understand where the different forces are without one.