By Jonathan North

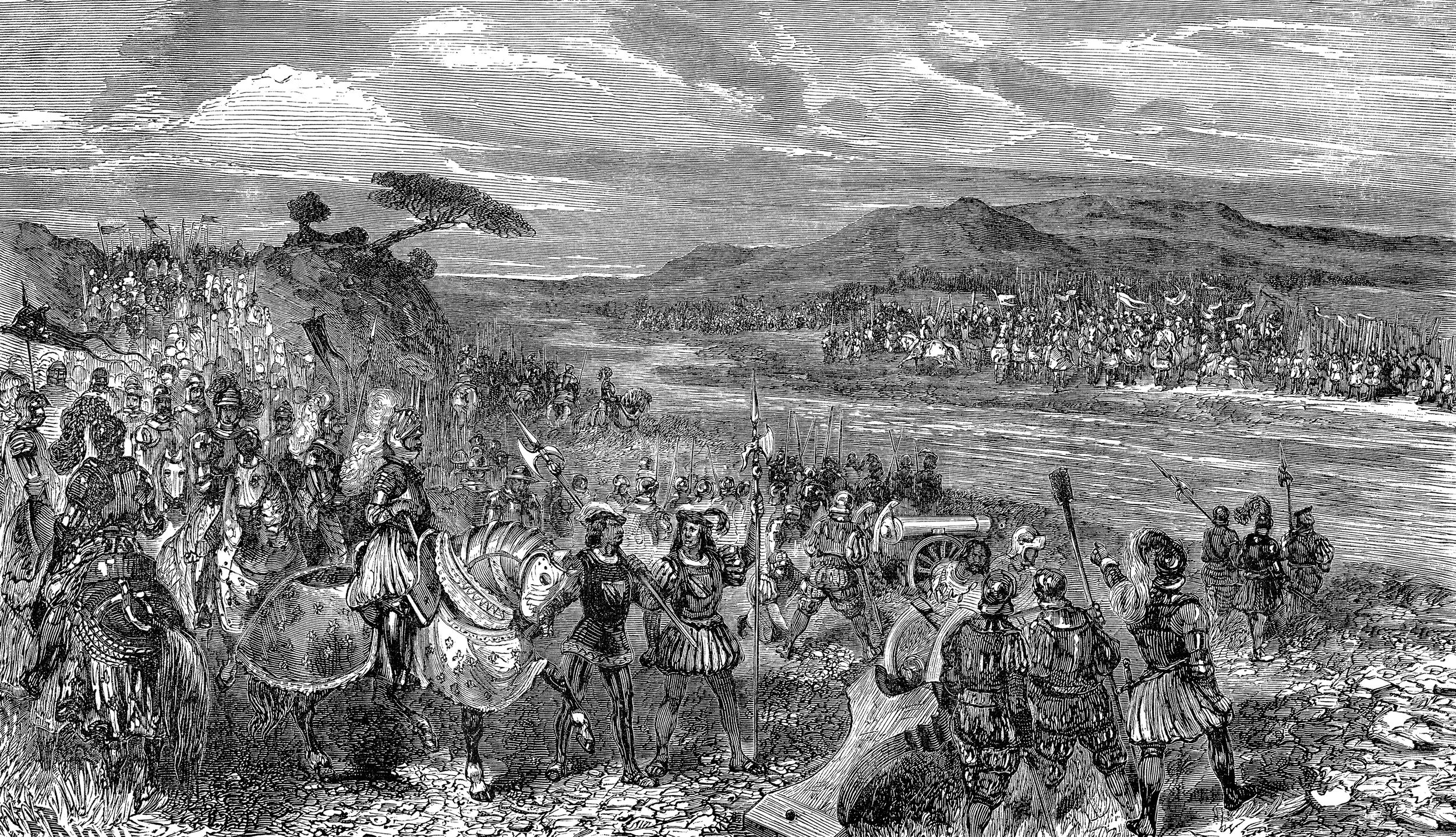

Fifteenth-century Renaissance Italian political life was a heady mix of intrigue, provocation and dispute, backed by limited wars and border raids. Yet, for all that, the major Italian states—Venice, Milan, Florence, the Papacy, and Naples—maintained an equilibrium and balance of power. All that changed forever in September 1494 when Charles VIII, the 24-year-old king of France, crossed into Italy with the declared aim of marching to the south of Italy and asserting his claim to the throne of Naples—a throne recently vacated by the death of King Ferrante.

Charles, ironically funded by Italian bankers (and by the jewels of the widow of the Duke of Savoy, pawned for 12,000 ducats), marched south against little opposition. He suffered a bout of smallpox at Asti but entered Florence in triumph. An Italian chronicler witnessed the scene: “The armoured horsemen presented a hideous appearance, with their horses looking like monsters because their ears and tails were cut quite short. Then came the archers, extraordinarily tall men from Scotland and other northern countries, and they looked more like wild beasts than men.”

Despite this rather unfortunate and xenophobic description, Charles and his army met with little resistance from the Italians and were, on a few occasions, well received. They managed to live off the land—although an officer in the French army complained that the wines of Italy were sour that year. After extorting 120,000 ducats from the Florentine government, Charles swept triumphantly into Rome on the last day of 1494 and entered Naples in February 1495. The subjugation of Naples was straightforward, the opposition fled, the French were warmly received, and they settled down to a semi-comfortable occupation.

The Holy League Against France

Their stay was brief. Alarmed by such brutal foreign intervention in the cloistered realm of Italian politics—with the nominal support of Maximilian the Holy Roman Emperor and Ferdinand of Spain—Venice, Milan and Rome formed the so-called Holy League on March 31, vowing to defeat the French and drive them from Italy. Giovanni Francesco Gonzaga, the 27-year-old, bug-eyed Marquis of Mantua and a mercenary in the pay of Venice, was elected to assemble and command the army of the League and was paid the handsome amount of 44,000 golden ducats to do so.

Charles, in Naples, was shaken by the news that his one-time allies Milan and Venice had rounded so abruptly against him and made hasty preparations for departure, calling in his garrisons, packing his loot, and making arrangements for the care of the sick—many of whom had succumbed to the “French Disease,” syphilis, then ravaging his army. On May 20 the French left Naples, white silk banners fluttering over the twisting column of troops, guns and wagons. Charles left five hundred men-at-arms and 2,500 of the vaunted Swiss mercenary infantry to contain the Neapolitans and the encroaching forces of Spain. These troops, too few to be of use in the south, would be sorely missed as Charles pushed northward and prepared to force his way through his enemies and back to France.

The French marched north, re-entered Rome—although the Pope, his Holiness Roderigo Borgia, fearing for his life, fled to Orvieto—and pushed on to Tuscany. Here, foolishly, Charles detached a number of men in a quixotic bid to aid Pisa in its attempts to liberate itself from Florentine rule, dangerously weakening his army yet again. The French marched over the Appennines, entered Milanese territory, and began to negotiate the surrender of Pontremoli. Here, something terrible happened, as recorded by Philip de Commines, Duke of Argenton and a veteran officer in Charles’s army: “The Swiss, contrary to their articles, now put all the men of the town to the sword, plundered the town, set fire to it, and burned it and all the magazines, with about ten of their own men who, being drunk, could not escape. After they had committed this outrage, they besieged the castle in order to do to those who were in it after the same manner. Neither would they give over their attack until the king himself sent to command them to desist. The destruction of this place was a great inconvenience to the king, as much for the dishonour it brought on us as for the provisions that were spoiled, of which there was great plenty, and we were in extremity of want.”

The next day the Swiss, now penitent and sober, made amends by hauling gun after gun of the artillery manually over the mountains. Artillery for the French was a key arm and their guns were vital. Charles’s artillery had reduced town after town in record speed and sown horror and dismay in Italy as recorded by the Italian chronicler Guicciardini: “The French had a great quantity of artillery of a sort never before seen in Italy and which rendered ridiculous all former weapons of attack. These were called cannon and they used iron cannon balls instead of stone as before. Furthermore, they were hauled on carriages drawn not by oxen as was the custom in Italy but by horses.”

King Charles III Faces the Adept Francesco Gonzaga

Meanwhile, the League, finding coalition warfare and the raising of a multi-state force problematic, after many delays got its army under way on June 21. The Italian commander, Gonzaga, was hampered by lack of information on enemy movements, political interference (the Venetians, who had hired Gonzaga, were keen that he only shadow the French and not commit to a major confrontation that would endanger their army), and the reluctance of the Milanese (the Duke of Milan feared a French army based in northern Italy under the rash Duke of Orleans and only sent two thousand men). Nevertheless, by the end of June, reassured by sheer weight of numbers, Gonzaga felt prepared enough to offer battle and closed in on the French as they moved toward the river Taro near the castle of Fornovo. Here he hoped to bring his overwhelming mass of cavalry into play as the French were in the process of crossing the river, cutting them to pieces and ending forever French intervention in Italian affairs.

It is something of a myth that Italian armies of the period were ineffective. Machiavelli and other Italian humanists, casting their eyes back to the glorious days of Rome, exaggerated the weaknesses of the Italian mercenary system. Yet, Italian commanders were renowned across Europe and had been employed by all the major European armies; their arms and armor were celebrated across the continent, and Venice, in particular, was a state experienced in fighting many different types of enemy and employing many different types of tactics. Charles was to face no soft option in his coming clash with the great Italian condottieri.

Gonzaga’s Stradiots

The armies drew within striking distance. There was a sharp skirmish on July 1 as the Italians sent their light cavalry to probe the French lines and attempt to unsettle their columns. Gonzaga used his stradiots, horsemen recruited in the Balkans and adept at skirmishing. Commines records the results: “Our troops were charged by the stradiots and one of our men (called Lebeuf) being slain, the stradiots cut off his head, put it upon the top of a lance, carried it to their commander and demanded a ducat. These stradiots are horse and foot, and dressed like the Turks, only they wear no turbans on their heads. Their horses are all Arabs and very good; the Venetians put great confidence in them. They are stout, active fellows and will plague an army terribly when they once undertake it.

“The stradiots having beaten our party, pursued them to the marshal’s quarters, where the Swiss were posted and killed three or four and carried away their heads. They did it on purpose to terrify us, and indeed they did, but the stradiots were no less terrified by our artillery; for a shot from one of our guns having killed one of their horses, they retired with great haste taking, in their retreat, one of our Swiss captains.”

The League’s soldiers did indeed capture a Swiss captain, called Hederlein, but inflicted little damage on the French whose morale was unshakeable and who were resolved to fight their way back to France.

The stradiots attacked again on the night of the 5th as the French were devouring a store of hard black bread they found in Fornovo. Again, little damage was done. That night was also marked by terrible storms, as Commines relates: “We had great rains that night also, and great claps of thunder and lightning, as if heaven and earth were coming together, or that this was some omen of impending mischief. But we were at the foot of a great mountain, in a hot country, and in the height of summer, so that the thing was natural enough.”

Yet the persistent rain added to the misery felt by many in the French ranks, a disquiet exacerbated by want and fear of the impending battle against a more numerous foe while far from home. That Sunday night few slept well as the rain swept down, wind extinguished the campfires, and men trembled in the cold and went hungry.

The French Prepare For Battle

At dawn on Monday, July 6 the French army, now just nine thousand strong according to Commines, crossed the Taro, which was swollen by the night’s rain, and continued its march which, inevitably, would mean that it would have to march across the front of the Italians on the far bank of the river. Charles divided his army into the traditional three “battles.” His vanguard, commanded by Rohan Gian Trivulzio (an Italian formerly in the pay of the King of Naples but now contracted to serve the kings of France) and Francesco Secco (a 72-year-old veteran)—both Italian mercenaries and sworn enemies of the Duke of Milan.

This vanguard was composed of six thousand men, including 1,600 French, four hundred Italian horsemen, and three thousand of the redoubtable Swiss infantry under Antoine de Bessey, the bailiff of Dijon—who promised his men triple pay if they managed to get the king out alive. In addition there were some German infantry (“a collection of people from all the countries on the Rhine, Swabia, the Pays de Vaux and Guelderland,” according to a French officer) under Enghelbert of Cleves, Scottish guard archers and Gascon crossbowmen.

Behind the vanguard came the main “battle,” commanded by Charles in person with the Viscount de Lautrec. Here Charles, sporting beautiful armor and riding on his superb charger, Savoy, placed 1,500 French horsemen, “the best mounted men I had ever seen,” according to one Italian, 250 mounted crossbowmen and a hundred Scottish archers of the king’s guard.

Behind them came the rear guard—1,800 horsemen under the Count of Guise. The French placed their artillery, 37 guns, 14 of them of substantial caliber, next to the river and to the right of the vanguard.

The final element of Charles’s army was the baggage train, which would play an important role in the coming struggle and, as the rest of the French army deployed, the heavy wagons were having difficulty getting forward. Despite the urgings of the officer in charge, Captain Odet, and its Breton and Gascon escort, the drivers were refusing to move. When the battle opened, the train was poorly protected, a little up the hillside to the French left (i.e., on the far side of the French position from the Italian viewpoint) and spread the whole length of the battle line making it easy prey for the League’s soldiers.

The Italian Formation

The French, just over nine thousand troops and five thousand camp followers and drivers, were confident of fighting their way out. Disturbed by rumors that Venice had offered a hundred thousand ducats for the king, dead or alive, they had prohibited the taking of prisoners and were sworn to sell their lives dearly. On the far side of the river the League, too, was making preparations for the battle. Gonzaga commanded 20,000 men officered by some of the best mercenary captains of the day—Rodolfo Gonzaga, a veteran of the Burgundian wars; Bernardino Fortebraccio, grandson of the famous Venetian mercenary; Alessandro Colleoni; Antonio Urbino, bastard of the Duke of Urbino; and Gianfrancesco Sanseverino, Count of Caiazzo, one of three exiled Neapolitan brothers in the League’s army.

Gonzaga’s force was centered on select men-at-arms serving in the or mercenary companies. He could also count on some of the best light cavalry of the day—recruited by Venice along the Adriatic and in its Balkan provinces. They were adept at skirmishing, being lightly armored and carrying scimitars—“terrible weapons, much to be dreaded” according to a French eyewitness—and rode small but swift horses. Infantry, whether pikemen, crossbowmen or scopettieri (hand-gunners) were despised and called “fanti” (boys) in derision and, despite their numbers, Gonzaga would not be relying on his foot soldiers in the coming clash.

At Venetian insistence, Gonzaga left six thousand Venetian infantry, four hundred light cavalry and 280 horsemen under Carlos de Melita to guard the League’s camp. He ordered Sanseverino with 2,320 horsemen and two thousand infantry (three hundred German mercenaries and 1,700 Milanese and reluctant Bolognese soldiers) to attack across the river and strike the French vanguard with the aim of stopping the French as they pushed along the riverbank. Colleoni’s men-at-arms, 250 horsemen, were to support the Milanese and formed up behind them.

The main attack was to come from the Italian center where Gonzaga himself commanded. Under his orders were 510 superb men-at-arms—the army’s best troops and largely commanded by members of Gonzaga’s own family, including his uncle Rodolfo Gonzaga—supported by five thousand infantry under Gorlino da Ravenna and seven hundred light cavalry (two hundred stradiots and five hundred mounted crossbowmen). In support of them rode Antonio of Urbino with a further five hundred men-at-arms from the Romagna and Papal states. These had been ordered to remain in reserve and to await Rodolfo Gonzaga’s orders.

On the far left of the Italian position Bernardino Fortebraccio commanded five hundred Venetian men-at-arms with orders to attack the French rear guard. Again, as was customary in Italian armies, these were supported by a second line—in this case Venetian cavalry under Benzone da Cremona. In addition, the League had sent an advance force across the Taro with orders to strike the French vanguard and main battle from the left. This force consisted of six hundred of Piero Duodo’s stradiots and Beccacuto’s five hundred mounted crossbowmen.

Attack on the French Vanguard

After saying Mass at around six in the morning, the impressionable Charles donned his gilded armor, made a brief speech to his main battle, stating: “I shall lead you back to France with honour, praise, and glory for us and our kingdom.” At nine the French artillery opened up and rained shot on the weaker Italian guns and Sanseverino’s infantry. The noise caused considerable disquiet along the entire Italian line and the bombardment terrified the Milanese and Bolognese infantry.

During the artillery duel, the League’s stradiots and crossbowmen came down from the hills and fell on the French vanguard’s left flank. They were beaten off with loss, two of their leaders being wounded, and made off to loot the poorly protected baggage train.

At around 10, with many of the Italian guns, which had been firing with little effect, already disabled, the rain, which would now continue throughout the day, came down in force and wet the French powder, forcing the artillery to fall silent.

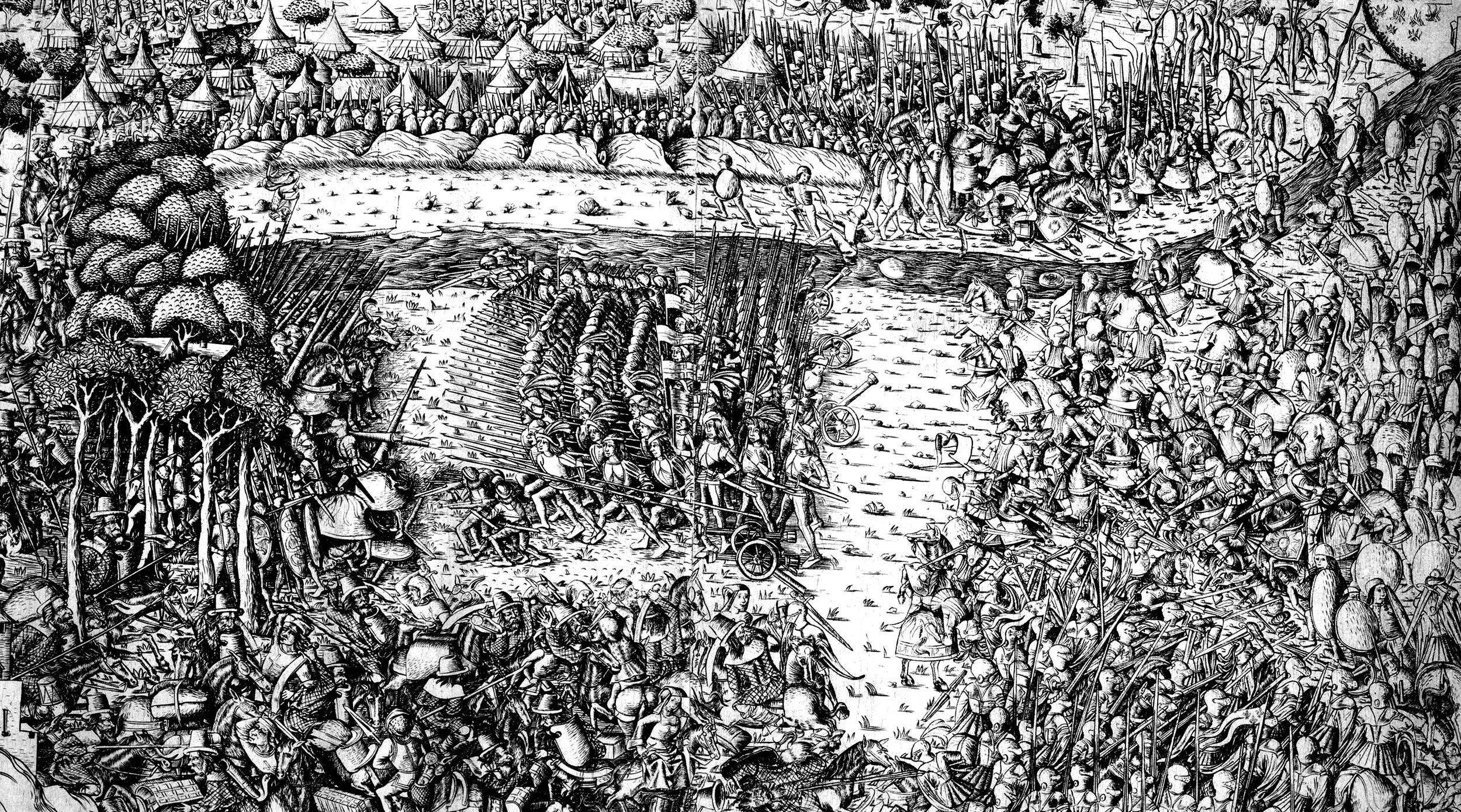

It was then that the League began the attack. Sanseverino’s troops pushed forward and, although shaken by the bombardment they had just endured, crossed the Taro and advanced against the French vanguard. As they drew nearer they saw that the Swiss were drawn up ready for them—three thousand superb troops formed up in a huge square, bristling with 12-foot pikes and surrounded by crossbowmen, arquebusiers, and picked men wielding formidable two-handed swords.

The League’s troops continued to advance but began to waver, now suffering losses from crossbows, and only a few of the Milanese closed with their enemies only to be pulled from their horses and slain by the Swiss. The rest of the Italian force broke and fled back across the river, most of the Bolognese making off the field of battle, throwing their weapons away, and fleeing for Parma some 15 miles away. Sanseverino called upon Colleoni’s troops to launch a second attack, this time aimed more at the French artillery but this, too, was beaten off with the Swiss knocking the Italians down with their lethally effective halberds.

Four Waves of Cavalry

As Sanseverino’s troops were losing the encounter with the vanguard, the League launched its main attack in the center. Rain had swollen the Taro, which ran in three main channels, and Gonzaga’s troops could only cross by moving a little to the right and finding shallow water. There was chaos in the muddy water; a number of Italian men-at-arms drowned when their horses slipped, and the crossing both delayed the decisive confrontation and badly tired the Italians. More of an obstacle was the far bank, which quickly became muddy with the passing of armored men and threw Gonzaga’s squadrons, and also those of Fortebraccio as they were endeavoring to cross, into disorder.

As they gained the bank, horses clambering noisily over mud and gravel and rearing and swerving to avoid ditches and hedges, they found themselves calmly opposed by the French rear guard under the Count of Guise. Somewhat overawed by the mass of Italian cavalry and supporting infantry, Guise could not profit from the disorder, but he was soon supported by the arrival of French troops from the main battle. This was the crisis of struggle; Charles had committed all his available men and was to pit them against the best troops Italy had to offer. Crucially the Italians had only a portion of their troops up, the rest remained in reserve, when Gonzaga launched his squadrons forward.

Gonzaga launched four waves of horsemen against the French despite being unsupported—the Italian light cavalry, stradiots, infantry, and even a few men-at-arms having been lured away to the left by the French baggage train. The attack, led by Gonzaga in person, came across rough terrain broken by dangerous waterlogged ditches forcing the horsemen to huddle together. The Italians, all-professional mercenaries and hardened soldiers, were a fine sight, yelling “Marco! Marco! Italia! Alla Morte!” and brandishing their Bourdonnasses (hollow lances, painted in bright colors). The dark, menacing masses of horsemen spurred on, shaking the ground under the weight of their attack. The French, tough gens d’armes eager for the fight and not given to the maneuvering enjoyed by Italian warriors, did not wait but closed ranks and advanced to meet the Italians shouting, “Montjoie! Saint Denis! France!” in an attempt to overawe the Italian horsemen.

The fight was savage but lasted just 15 minutes. The French, with lighter armor, more practical swords, lethal maces, and more effective lances were at the advantage and managed to sweep around the right flank of Gonzaga’s and Fortebraccio’s battle groups, causing havoc in the Italian ranks. The melee cost the Italians dearly. Rodolfo Gonzaga was among the first to fall; his corpse was found after the battle and sent in state to Mantua. Fortebraccio was wounded 12 times before falling from his horse. He was to survive, despite being wounded again, in the neck, by looters pushing their swords through his armor in an attempt to slit his throat.

The Italian Withdrawal

Before long, the Italians turned about and made their way back across the river, some stampeding in panic and throwing supporting infantry into disorder. Their reserves had not moved forward, having received no orders to do so. The French, astonished by their success, warmly pursued and even contemplated crossing the river to decide the battle. As they did so, they left their king isolated, as Commines relates: “The king remained in the same place, and so ill-protected that of all his squadron he had none left but Anthony des Aubus, a little man and but poorly armed; the others were all dispersed and they ought to have been ashamed of themselves. A small party of the enemy coming along the road and perceiving it so thin of men, fell upon the king and the aforesaid gentleman; but the king, by the activity of his horse, kept them at bay until the others came up and then the Italians were forced to fly.”

Meanwhile, as the Italians fell back, the French infantry swarmed over the scene of the clash of the Italian and French men-at-arms, the whole area of which was covered in dead, wounded and dismounted stragglers. The French, contrary to the rules of Italian warfare, spared none, as Commines relates: “We had a great number of grooms and servants with our wagons, who flocked about the Italian men-at-arms, when they were dismounted, and knocked most of them on the head. The greatest number of them had their hatchets (which they cut their wood with) in their hands, and with them they broke up the helmets, and then knocked out their brains; otherwise they could not easily have killed them, they were so well armed; and to be sure there were three or four of our men to attack one men-at-arms. The long sword which our archers and servants wear also did great execution.”

Gonzaga and what little remained of his battle group crossed the river in good order and rallied a number of troops. Fugitives followed, although many were again drowned in the muddy and slippery river; those who survived passed through the ranks and swelled the number of fugitives heading for Parma or Reggio and shouting that they had been betrayed. Venetian officers stationed by the camp did a good job in rallying some of the fugitives as did Count Orsini, a prisoner of the French recently released from the baggage train. Orsini even urged Gonzaga to attack again as, despite the casualties, the Italians still outnumbered the French. Gonzaga did not, fearing a complete rout and an end to his own military career (and therefore to his Duchy and title of Duke).

Neither did the French follow up on the victory, despite the urgings of the Italian mercenaries Trivulzio and Vitelli to cross the river and finish the business. Charles and his French officers, however, felt they had done enough and were content as they had reopened their route to safety. The rain was still falling, the river still rising. Charles felt it was enough to reform his ranks and face the enemy, come what may.

The Fate of King Charles VIII

That afternoon the two armies faced each other as though preparing for a renewal of the struggle, although the prescient Charles and five hundred communicants knelt and celebrated Mass that night, joyful in their deliverance. Charles, who spent the night in a cottage or farmhouse, was very cheerful but spent a most uncomfortable night, as did Philip de Commines: “For my part, I remember lying in a little pitiful vineyard, upon the ground and without any shelter; for the king had borrowed my cloak in the morning and my baggage was not to be found. He that had anything to eat kept himself from starving; but very few had victuals more than a crust of bread or so, which they took from their servants.” Meanwhile, the French valets and infantry thoroughly stripped the dead and wounded, and peasants from the surrounding area flocked in to help themselves to anything of value including armor, saddles, horseshoes, rings, money and even clothes and blankets.

Toward evening the French sent their artillery on, fearing the Italians less and less as time wore on. In the morning a truce was arranged to collect the wounded and, under cover of Commines’s detailed negotiations, the French army slipped away toward safety.

The Italian pursuit was feeble. Gian Sanseverino, brother of the Count of Caiazzo, shadowed the French with five hundred Venetian light cavalry despite the League still having overwhelming superiority in numbers. Only on the 10th did the League’s main body break camp and advance. Less than a week later, Charles was safe in friendly territory and enjoying rich supplies in Asti.

The campaign dragged on for another few months. Then there was a brief lull and the direct intervention of fate. Charles, busy intriguing with the Venetians and planning a second invasion of Italy, passed the spring of 1498 in his castle at Amboise. On his way to watch a game of tennis he knocked his head against the frame of a door and died the next day.

Gonzaga’s Spoils of War

So ended the campaign that was to decide Italy’s fate for the next half century. Gonzaga at first announced a complete victory. The Italians had, it was true, remained on the field and the French retreated, hounded out of Italy by the victorious League and leaving behind them considerable booty.

And indeed a vast amount of booty fell into Italian hands. Gonzaga’s troops had thoroughly looted the French baggage wagons and found, among other treasures, such riches as Charles’ gilded tournament helmet (which, according to Italian propaganda, belonged to Charlemagne), his ceremonial sword, cloth of gold, the golden seal of France, a piece of the Holy Cross and a Sacred Thorn, a limb of St. Denis, maps and charts, the Royal Library and, so the League alleged, a book containing pictures of all the Italian beauties Charles had known on his Italian expedition.

These trophies were paraded through Parma and Gonzaga was appointed captain-general of the Venetian army in token of his “victory.” Gonzaga in turn celebrated his own personal triumph by building a chapel in Mantua and commissioning Andrea Mantegna to decorate it with a painting showing Gonzaga himself thanking the Virgin Mary for victory. (Ironically this painting now hangs in the Louvre in Paris, stolen in 1797 by that other French adventurer in Italy, Napoleon Bonaparte.)

How Did the Holy League Fail to Defeat the French?

Yet, before long, reality set in. The French had escaped. More than that, they had inflicted a check on an army of 30,000 with just 10,000 men. Figures vary but it seems that the French lost very few prisoners and had some one thousand casualties at most. The League lost much more heavily—Gonzaga’s mercenary company alone lost 250 men, or half its original strength—some four thousand men, most of them killed during the rout. The dead included Ridolfo Gonzaga, Giovanni Maria da Gonzaga, Alessandro d’Este, Giorgio Arozzi, Giovanni Picinnino, Galleazo da Corregio, Alessandro Beraldo and Roberto Strozzi—great names in Italian warfare. Many men had drowned, and for the next two weeks bodies could be seen floating down the Taro from the walls of Parma. Most of the dead received a common burial, although some were burned, but the bodies of members of the Gonzaga family were sent to Mantua for burial.

The French seemed to have lost but few men. About two hundred cavalry were killed along with eight hundred infantry, mostly from those guarding the baggage train. Few men of note were killed, although casualties included Guinot de Louviers, commander of the artillery; Julien Bourgneuf of the Guard; Captain Odet; and the Italian Francesco Secco.

Before long the recriminations began. Gonzaga blamed the for not doing their job and for falling on the baggage, and he reprimanded Duodo for not deploying his troops to the best advantage. With hindsight the stradiots had behaved badly but so too had Sanseverino’s men, Gonzaga’s infantry and light cavalry, and the whole second line, which had not budged in support of their comrades. Gonzaga himself was later accused of having led more like a squadron leader than the commander of an army— leading from the front and failing to appreciate the wider picture. As his former teacher wrote to him after the battle: “I am horrified by the risks that you personally ran. Behave like a commander on a battlefield and don’t play the mercenary or squadron leader.”

The truth was spoken, too, by the wounded Bernardino Fortebraccio, who addressed the Venetian Senate in the following terms: “I have to say this, for I cannot keep it back. We could have defeated their army, or even a larger one, if our people had attended to the battle and not to the baggage train.”

Fornovo was a short and bloody encounter with serious consequences. The French were surprised by the poor showing of troops raised by such sophisticated and rich political systems. The Italians acted without unity and without firm resolve. Gonzaga, when he did strike, concentrated on launching his own attack and did not take account of the larger picture. At the key moment, the French outnumbered the Italians.

A secondary reason for the defeat was the lure of the baggage train and the ineffective use of the League’s infantry and light cavalry. Even when the main assault had been beaten off, the Italians still had more troops on the field than the French; thus their reluctance to attack again or pursue the French with energy was inexcusable. Well did Guicciardini write that, “On the banks of the Taro, with more bravery than reflection, we lost the Italian reputation for warfare.”

The combination of rich pickings for foreigners and poor military resolve made Italy a tempting target for future intervention, not just by France but by such other powers as the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. The stage was set for the Italian Wars—a half-century of destructive warfare with Italy, having given a sign that she was weak in 1494-95, now lying prostrate before foreign powers vying for control of the rich rewards on offer in the peninsula. Italy was embarking upon three hundred years of foreign domination and a brutally enforced subservience to belligerent northern powers.

Defeat is a bit harsh. French passed, yes. But left everything and basically ran away