By Pat McTaggart

“We felt that we were already dead men,” wrote former Captain Albrecht Wüstenhagen in a May 1988 letter to the author of his time in the fortress garrison of Küstrin. In 1945, Wüstenhagen found himself in command of an infantry gun company, part of the garrison, estimated at between 9,000 and 16,000 men and boys, in the small town on the eastern bank of the Oder River, some 70 kilometers east of Berlin. On January 25, by order of Adolf Hitler, Küstrin had been made a Fortress Town, meaning that it was to be held to the last man and last bullet. The penalty for retreat was death. It was here that the prelude to the Battle of Berlin would take place.

The History of Küstrin

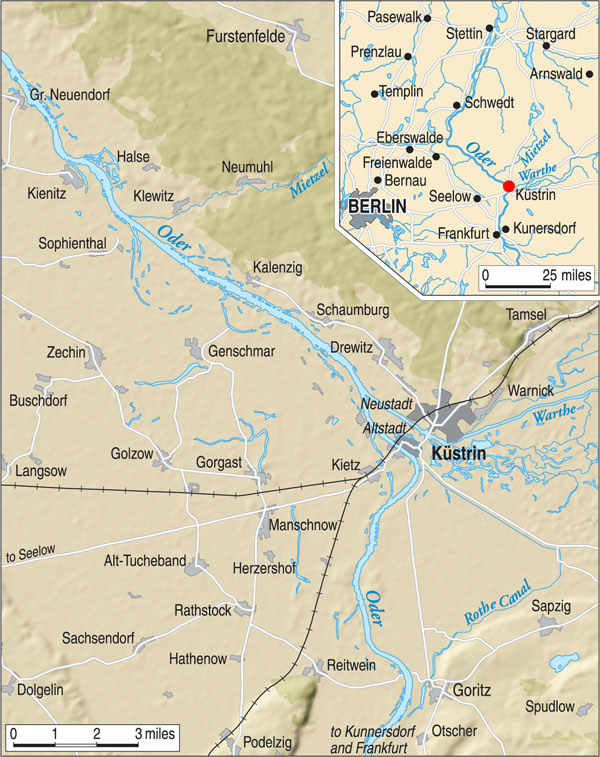

Küstrin was settled by Slavic tribesmen in the 10th century. The Knights Templar claimed the settlement in the 13th century, establishing a market there and receiving a charter as a city, creating a soon to be flourishing community. In the mid-1500s a castle and fortress were constructed, and other fortifications were gradually added. The primary fortifications were located in the Altstadt (Old Town) on a peninsula at the confluence of the Oder and Warthe Rivers.

In 1758 the town was besieged by the Russians. The surrounding wooden buildings were destroyed, but the fortress held firm. Half a century later the French were luckier, and the town was garrisoned by Napoleon’s forces from 1806-1814. In 1857 the construction of a railroad line was completed, making Küstrin an important railway hub, and a Neustadt (New Town) grew on the eastern side of the Altstadt.

With the unification of Germany, Küstrin acquired a new artillery barracks, which was finished in 1903 on an island across from the Altstadt railway station. That was followed by the construction of an engineer barracks in 1913. After the defeat in World War I, many of the town’s fortifications were ordered destroyed under the provisions of the Versailles Treaty.

The Eastern Front Becomes a House of Cards for the Germans

Following the rise of Hitler, Küstrin found a new prosperity after the devastating Great Depression. By 1939 its population stood at about 21,500. That figure diminished as the war took more and more young men into the Wehrmacht. However, even by late 1944 the war seemed far away on the eastern side of the Vistula River, and the people led relatively normal lives. That would change in January 1945.

Hitler had been repeatedly warned about an impending Soviet offensive. His intelligence officers for the Eastern Front reported a massive buildup of men and matériel, which was ridiculed by the Führer. He was convinced that the Russians had bled themselves dry, and he was more focused on the Allied threat in the West. When confronted by General Heinz Guderian, his Army chief of staff, Hitler flew into a rage as he was presented with the intelligence estimates on one sector of the Vistula Front on January 9.

“He declared them to be completely idiotic,” Guderian wrote in his memoirs. Hitler also ordered the man who compiled the report locked up in an insane asylum.

Guderian did not back down. “The Eastern Front is like a house of cards,” he replied. “If the front is broken through at one point all the rest will collapse, for 12 and a half divisions are far too small for so extended a front.”

“The Eastern Font must help itself and make do with what it’s got,” was Hitler’s final word. Three days later, the Soviets attacked.

Guderian’s “house of cards” collapsed on January 12, when the Russians unleashed the Vistula-Oder Operation. At 04:35 Soviet artillery, amounting to 230 guns per kilometer, opened a devastating barrage on General Maximilian Reichsfreiherr von Edelsheim’s XLVIII Panzer Korps, which was trying to contain Soviet forces inside the Baranov Bridgehead in Poland. It was a Panzer Korps in name only, consisting of only three weak infantry divisions, the 68th, 168th, and 304th.

The German Line Disintegrates

Following the barrage Red Army tanks and infantry of the 3rd Guards Army and 4th Tank Army from Marshal Ivan S. Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front surged forward. Von Edelsheim’s defenses were shattered. In a 1981 letter to the author he wrote: “There was absolutely nothing to be done. The Soviet barrage was astounding and our infantry simply disappeared. By noon my three divisions no longer existed and those that survived were fleeing for their lives. We were simply swept aside or destroyed.”

That was only the beginning. The entire German line was torn asunder as more Soviet fronts joined the offensive in the next few days. Warsaw fell to Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front on the 17th, while Konev continued the drive on his left.

The Russian offensive exploded on most sectors of the Eastern Front as Soviet forces hit everything from East Prussia to the Slovak border. German troops were fighting for their lives in Königsburg and Budapest, while Soviet forces pushed their way into the industrial region of Silesia.

In Küstrin, the people went about their daily business. The war had taken most of the men of military age, and those on the streets were mostly children, women, and the elderly. On the radio Nazi propaganda touted the invincible “Eastern Wall,” and if anyone doubted that claim they kept it to themselves. Then the refugees started coming. At first it was just a trickle, but it soon turned into a flood.

The first ones were from the west, fleeing the devastating Allied air attacks on major German cities. For most of them Küstrin was just a stopover on their way to other destinations. Things started changing as the flow reversed and refugees began coming in from the east. The first wave was composed of Nazi officials and their families. They were followed by civilians using whatever transportation they could get, and they brought troubling stories of Russian advances and Wehrmacht retreats.

People started to get nervous and that feeling grew as the local Volkssturm battalion, composed mostly of teenage boys and those men who were either unfit or too old for military service, was mobilized on January 24. There was now little doubt that something was going very wrong to the east.

The Laughable “Fortress Küstrin”

Just how wrong became evident on January 25, when the Führer Order declared Küstrin a fortress with Maj. Gen. Adolf Raegener as its commander. The grandiose title “Fortress Küstrin” was almost laughable. There was a scattering of engineers and artillery units in the town, as well as some infantry units consisting of trainees or men convalescing from their wounds. Defensive positions were negligible, as most had been neglected or destroyed in the preceding years, and the frozen ground made digging earthworks difficult. Moreover, the Soviets were reported to be only about 70 kilometers away.

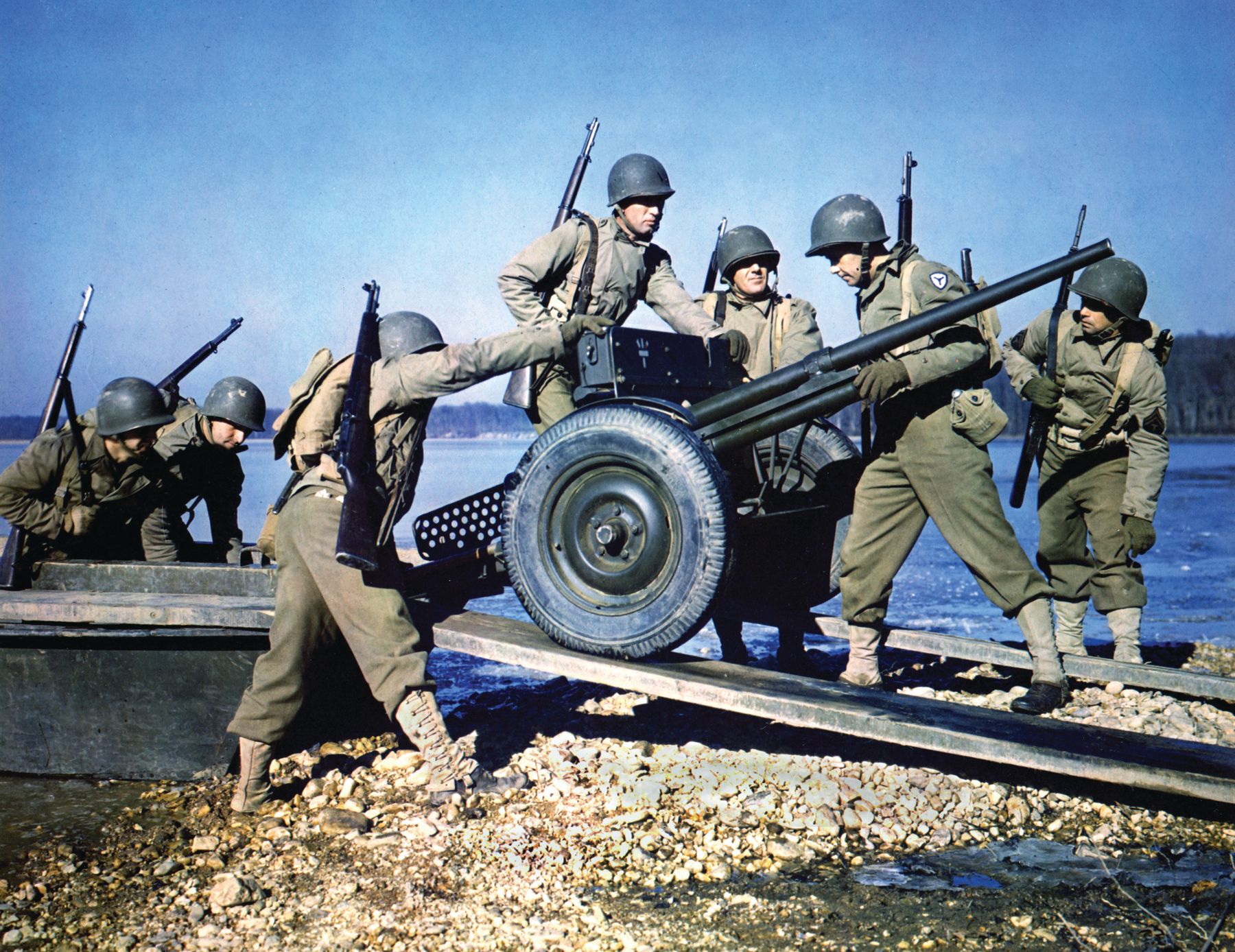

During the final days of January, the garrison of Fortress Küstrin began to grow as a variety of small units, of which Wüstenhagen’s was one, started to arrive in the town. The fortress’s antitank weapons, of which there were few, were strengthened by the arrival of a few Panther tank turrets. Sporting 75mm guns, the turrets were embedded in strongpoints along likely avenues of attack.

As more units trickled in, the defense force became a little more organized under Raegener’s direction. It was also very diverse.

“There were some Luftwaffe personnel from flak units, some of which no longer had their flak pieces,” Wüstenhagen recalled. “We also had an Einsatz (action) battalion made up mostly of Turkomans, a Moslem people, as well as one made up mostly of troops from the Caucasus. There were Hitler Youth, Volkssturm, some Hungarians, and even some members of the Waffen SS. Some men were individuals who had been separated from their units and had been stopped by the Kettenhunde (literally chain dogs—soldiers’ slang for the German Field Police that referred to the metal gorgets they wore on their chests) and forced into serving with the garrison. It seemed that this mix of units would be able to do little against the Russians, but General Raegener, and later SS General Heinz Reinefarth, worked hard to turn us into a real fighting force.”

While the Germans went about trying to strengthen meager defenses, the Soviets kept moving westward. After taking Warsaw, Zhukov’s front had advanced another 120-130 kilometers in the period January 20-22. By the 25th, Col. Gen. Vasili I. Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army, following in the wake of Col. Gen. Mikhail E. Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army, had the 60,000 men of Fortress Posen (present day Poznan) surrounded. Leaving parts of both armies to besiege the city, Zhukov ordered both commands to keep moving westward.

The Tip of the Spear: Chuikov and Katukov Approach the Oder

Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front was a powerful force. Besides Katukov’s and Chuikov’s armies, he had the 2nd Guards Tank Army (Col. Gen. Semen I. Bogdanov), 3rd Shock Army (Lt. Gen. Tikhon K. Simoniak), 5th Shock Army (Lt. Gen. Nikolai E. Bezarin), 33rd Army (Col. Gen. Viacheslav D. Tsvetrev), 47th Army (Lt. Gen. Frants I. Perkhorovich), 61st Army (Col. Gen. Pavel A. Belov), 69th Army (Lt. Gen. Vladimir I. Kolpakchi), and Lt. Gen. Zygmunt Berling’s 1st Polish Army.

Chuikov and Katukov were the tip of this massive spear. Zhukov wanted them to reach the Oder quickly and establish bridgeheads on the western bank. The following forces would eliminate German strongpoints, such as Posen, and then spread out along with Katukov and Chuikov to consolidate positions on the eastern bank to prepare for the final drive on Berlin.

Zhukov was already planning his next actions. In his memoirs he wrote: “Around noon on January 25 I had a telephone call from Stalin. I briefed him on the situation, and he inquired about our next moves. I said that since the enemy was demoralized and unable to put up serious resistance, we would continue to drive toward the Oder and attempt to seize a bridgehead at Küstrin.”

However, Stalin was worried about Zhukov’s right flank. Marshal Konstantin K. Rokossovski’s 2nd Belorussian Front was heavily engaged in East Prussia, and with Zhukov speedily advancing there would be a gap of about 150 kilometers between the two fronts until Rokossovski could clear East Prussia and move up to the Oder. Stalin did not want that gap left open.

Zhukov shifted his forces accordingly. He ordered the 1st and 2nd Guards Tank Armies, most of the 8th Guards Army, and the 33rd and 61st Armies to keep moving toward the Oder and had the 3rd Shock, 47th, 69th, and 1st Polish Armies, supported by Lt. Gen. Vladimir V. Krukov’s 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps, swing north and northwest to secure his right flank.

At Küstrin, work continued on strengthening the defenses. “We officers worked beside our men,” Wüstenhagen wrote. “The materials on hand were limited, but as more and more refugees from the east continued to come through the town, we worked even harder for we knew that Ivan was close.”

“Ivan” was indeed close, but Mother Nature now took a hand in events. A blizzard hit central Europe on January 27-28. Mounds of snow piled up in the roadways, slowing Zhukov’s mechanized and motorized forces to a crawl.

“The blizzard gave us a few more days,” Wüstenhagen wrote.

Zhukov also had other problems, despite his optimism. His rapid advance was becoming a logistics nightmare as supply lines grew longer and longer. Columns had to travel up to 200 miles from depots to furnish the frontline units with gasoline, ammunition, and other materials needed to keep going. There was also the fact that German forces facing his northern flank were putting up much more resistance than expected.

During the last days of January, the weather turned warmer, and the snow that had fallen during the blizzard began to melt, turning the once frozen ground into a slimy mass of mud. Zhukov’s forces were once again slowed to a snail’s pace, but on the 31st the forward elements of his front reached the Oder north of Küstrin.

The flow of refugees into Küstrin suddenly stopped on the 31st. It was an ominous warning to the garrison. Early in the afternoon a column of Soviet tanks came through the village of Drewitz, just north of Küstrin. They rolled over a group of panzergrenadiers assigned to a defensive position and then spread out, looking for other targets.

A group of about a dozen tanks, many of them American Lend-Lease Shermans, made their way through the outskirts of Küstrin and into the Neustadt. They kept on going toward the Warthe bridges but were stopped by an influx of panicked civilians whose vehicles had created a traffic jam at a major intersection. Finding their way blocked, the tanks turned around and searched for another approach to the river.

The garrison had been caught completely by surprise by the initial penetration, but by the time the Soviets reached the heart of the Neustadt the alarm was finally given, and tank-killer teams started to hunt the Russian armor. Surprisingly, only a few tank-riding infantry accompanied the tanks, and German forces soon began picking off the Soviet raiders with panzerfausts or sticky bombs. In the end, only four tanks made it safely back to their lines.

Logistical and Tactical Challenges for the Soviet Advance

Zhukov had reached the Oder, but the Soviet marshal now had to face several obstacles. His first order of business was to establish his bridgeheads on the western bank of the river. One was established at Kienitz, about 20 kilometers north of Küstrin, and another one was established south of the town at Göritz.

Supplies were also becoming more of a problem. His forces had advanced up to 400 kilometers in a little more than two weeks, and the wear on the vehicles had been enormous. Parts, as well as supplies and ammunition, were needed before any other large-scale operation could commence.

His right flank was also a matter of concern. There was still a strong enemy presence there, and Zhukov’s northern blocking force was strung out and repulsing German attacks in that area.

Another matter was reinforcing his armies. During the drive to the Oder, the 1st Belorussian Front lost 17,032 men killed and had another 60,310 sick or wounded—about seven percent of its total manpower. Zhukov knew that for the final assault on Berlin his forces would have to be up to full strength.

Stalin and STAVKA (the Soviet High Command) came to the same conclusions. On February 2, Moscow declared the Vistula-Oder Offensive officially over. Zhukov was now free to consolidate his gains, but there were still two thorns in his side: the German bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Oder at Kunersdorf near Frankfurt and the bridgehead of Fortress Küstrin.

The appearance of the Soviet spearhead in the center of Küstrin led to an even greater intensity in fortifying the town. Wüstenhagen recalled working 16-18 hours a day shoring up antitank defenses and building machine-gun strongpoints to protect his guns.

Elements of Maj. Gen. Arnold Burmeister’s 25th Panzergrenadier Division (PGD) established themselves on the western bank of the Oder across from the town. The 25th had been badly mauled in the Soviet summer offensive and had been rebuilt in October. Those elements that had survived the January winter offensive formed a wedge between the Soviet bridgeheads at Kienitz and Göritz.

They were joined by Maj. Gen. Rudolf Hübner’s 303rd “Doberitz” and Brig. Gen. Heinrich Voigtsberger’s 309th “Berlin” Infantry Divisions, both of which were newly formed and understrength, and the staff of the still forming “Kurmark” PGD. Also forming around Captain Horst Zabel’s Panzer Detachment Kummersdorf was the soon to be Panzer Division “Muncheburg” which would be commanded by Brig. Gen. Werner Mummert.

As some civilians began their exodus from Küstrin westward toward Berlin, other troops were crossing into the town. So far, the Red Air Force had not mounted missions against the garrison, which was lucky for the defenders since they had little antiaircraft protection at first.

Germany’s Adolescent Army Arrives to Help Defend Küstrin

“During the beginning of February we finally got some light flak guns into the town,” Wüstenhagen wrote. “They were manned by a mixed group of Luftwaffe personnel and Hitler Youth, boys as young as 12 or 13. It was a welcome sight to see the guns but it was disturbing to see the youths that manned some of them. We had no more men to fight, and we were now using children. Surely the war could not go on for much longer.”

Although the surprise Soviet tank thrust into the town had failed, the Russians continued to funnel troops into the Küstrin area and were already launching probing attacks. As early as the morning of February 1 a Soviet unit had managed to take a factory on the northwest edge of the town, killing or routing a combined Hungarian-Volkssturm force occupying it. A German counterattack later in the morning finally cleared the building after bitter fighting.

On that same day Raegener was replaced by SS Maj. Gen. Heinz Reinefarth over the objections of the Army. Reinefarth, who had been a member of the SS since 1932, had been awarded the Knight’s Cross in 1940 for his actions during the invasion of France while serving as a reserve sergeant in the Army (it was possible for members of the SS to also serve as regular Army personnel). He was promoted to SS brigadier general in 1942 and was made general inspector of the SS in the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia.

In September 1943, Reinefarth was transferred to Berlin where he served in the Hauptamt Ordnungspolizei (ministry of the order police). January 1944 found him serving as SS and police leader in the Reichsgau Warttheland, a former Polish province that had been annexed by the Germans after the Polish defeat. In that capacity he took part in the bloody suppression of the Warsaw Uprising in August, for which he was awarded the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. His most recent post was commander of the XVIII SS Korps.

Reinefarth’s appointment was political, as he had virtually no command experience except for the past month and a half. Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, who was serving as the inept commander of Army Group Vistula, wanted one of his own to defend the town, and Reinefarth was his choice instead of a combat-savvy Army officer. In his memoirs, Guderian remarked that Reinefarth “was a good policeman, but no general.”

Even though the Soviet forces directly involved in the Küstrin sector fighting were still relatively weak, Zhukov ordered Chuikov to keep as much pressure on the garrison as possible. After the failure to hold the factory in the north, Chuikov ordered an attack on the southern sector of the town, which was repulsed with the loss of three tanks. Encouraged by that success, Reinefarth ordered an attack of his own to retake the Warnick area just east of Küstrin. The attack failed miserably in the face of heavy Soviet fire, costing the garrison several casualties.

Winter Weather Bolsters German Efforts to Reinforce their “Fortress”

A Russian attack on February 3 seized a German strongpoint about one kilometer southwest of the town, while another gained about 100 meters of ground in another sector. Despite these successes, the Soviets were confined to mostly reconnaissance attacks since there were still too few troops in the area for an all-out assault

The thaw that followed the January blizzard was still raising havoc with troop movements. Even so, Stalin ordered Zhukov to siphon off more troops of his front to deal with the troublesome Germans that were still offering stiff resistance in the north. His forces did have limited success when they managed to seal the supply route on the west bank of the Oder, isolating the Küstrin area. The success was short lived as the timely arrival of Colonel Helmut Zollenkopf’s depleted 21st Panzer Division managed to open a thin corridor that once again gave Küstrin a lifeline to the west.

By the end of the first week of February, both sides had settled into a routine, with the Soviets firing artillery into the town around mid-day and constantly mounting nuisance attacks and the garrison working to shore up its defenses between artillery barrages. After an inspection of the Küstrin sector, Col. Gen. Chuikov described the difficulties faced by the Russian troops.

“The [Küstrin] Citadel itself was set on an island formed by the Oder and Warthe Rivers. The spring [sic] flood had submerged all the approaches to the island. The only links between the Citadel and the surrounding land were dikes and roads fanning out toward Berlin, Frankfurt, Posen, and Stettin. Needless to say, the enemy had taken care to block these roads securely, covering the dikes and embankments with dugouts, pillboxes, trenches, caponieres, barbed wire, minefields, and other defenses. Our small sub-units managed to come so close to the enemy fortifications that hand grenade and panzerfaust exchanges went on around the clock. But we were unable to deploy large forces here since a single tank took up the whole width of a dike.”

Despite the Soviet harassment, the garrison had now created somewhat cohesive defenses. In addition to the approximately 6,800 civilians still in the town, there were approximately 9,100 members of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS and 900 Volkssturm defending the fortress. At times the strength was estimated to be about 16,000 due to the arrival and departure of various units. An estimated 102 artillery pieces, 30 flak guns, 50 mortars, 25 self-propelled guns, and 10 captured Katyusha rocket launchers (Stalin’s Organs) were also in the fortress at various times.

Reinefarth divided the town into two defensive areas. The Altstadt sector, which also included Kietz, the island, and the surrounding area, was under the command of Eastern Front veteran Major Otto Wagner, who had received the German Cross in Gold in March 1942 while commanding a battalion of the 32nd Infantry Division in the Demyansk area.

To command the Neustadt defensive sector, Reinefarth chose a Colonel Walther, a field police commander with even less combat experience than Reinefarth himself. It was a poor choice, especially since the Neustadt was more vulnerable than the Altstadt position.

Since the weather precluded any strong ground assault, the Soviets stepped up their artillery fire and also launched mostly platoon- and company-sized reconnaissance attacks. In one case, a tank-supported battalion gained some vital ground just south of the fortress. A vigorous counterattack involving close combat finally forced the Russians to retreat after both sides had sustained numerous casualties.

More Artillery, More Attacks: the Soviets Increase The Pressure on Küstrin

Zhukov ordered more artillery into the Küstrin sector. Between the heavy mortars, rockets, and guns of the Red Army artillery, movement inside the fortress became more and more difficult. Rubble from the shattered buildings clogged the streets, and the town’s fire department was hard pressed to douse the flames that seemed to be everywhere.

“We could engage the Russians in counterbattery fire,” Wüstenhagen wrote. “But since our supplies were not great, we were limited to the number of shells that we could use. It seemed like for every 20 Russian shells fired, we could only fire one or two. However, we had some good [artillery] observers, and we would not waste our ammunition unless we definitely knew where the target was located.”

The Russian shelling was also aimed at the defensive positions at Kietz. In mid-February they stepped up attacks around that town, hoping once again to cut the supply corridor to the fortress, but the forces defending the area managed to prevent any major breakthroughs.

In one such attack, two T-34 tanks that were supporting a Soviet infantry attack fell victim to the terrain as they became mired in the mud. From their defensive positions, German forces fired on the stalled infantry, who were reluctant to advance without tank support, and forced them to retreat.

On February 19, civilians in the Neustadt were notified that they would be evacuated. For the next few days, approximated 2,000-3,000 people made their way across the Oder and headed west through the narrow supply corridor under cover of darkness. Surprisingly, the Soviet artillery was relatively quiet, and the evacuation was carried out with few casualties.

Even as the last of the evacuees were leaving the Neustadt, the remaining residents of the Altstadt were receiving their marching orders. Although ordered to leave, several hundred residents refused to give up their homes and belongings and chose to remain in both sectors.

While the evacuations were taking place, the garrison was kept busy repelling spotty Russian attacks on Küstrin’s defenses. The fortress, now under the tactical command of SS Lt. Gen. Matthias Kleinheisterkamp’s XI SS Panzerkorps, had received orders from Panzerkorps headquarters stressing the importance of holding the town. Besides preventing the Russians from taking the bridges spanning the Warthe and the Oder, they were to harass other Soviet crossing points within range of the fortress artillery.

“We were suddenly receiving many more shells from the supply convoys that came through at night,” Wüstenhagen recalled.

During the final days of February, the Soviet artillery increased dramatically. Choice targets for the Red Army guns were positions around the cellulose factory, located about 300 meters east of the Friedrich-Wilhelm Canal, and positions in Kietz. Reinefarth and his commanders became convinced that these barrages were a prelude to a massive attack, but none materialized.

While the Soviets continued their artillery fire, the boys of Küstrin’s Hitler Youth, who were helping the garrison defenders, were ordered to evacuate. Some of them protested the order but grudgingly obeyed.

“We could only hope for the best for those young boys,” Wüstenhagen wrote. “They were helping us the best they could and freed up men for the front line, but we were happy to see them get out of danger.”

Rain pelted the Küstrin sector during the first days of March, making life miserable for both sides. It also masked Soviet movements on the northern sector of the fortress. Maj. Gen. Dmitrii S. Zherebin’s 32nd Rifle Corps of Berzarin’s 5th Shock Army was closing in with its 60th Guards Rifle Division (Maj. Gen. Kirill K. Dzhakhua) and the 295th and 416th Rifle Divisions (Maj. Gen. Aleksandr P. Dorofeev and Maj. Gen. Dmitrii M. Syzranov).

Zherebin planned to attack the Neustadt, driving toward the Warthe bridges. Kietz would also be the object of an attack by other units. Four regiments, supported by heavy and medium tanks, would form the main assault, although the tanks would have a difficult time in the muddy terrain.

The assault was preceded by a massive artillery bombardment on March 6. The Neustadt was soon shrouded in smoke from burning buildings throughout the area, which would be helpful in masking Russian movements.

“The explosions of the enemy shells were deafening,” Wüstenhagen recalled. “We had not yet experienced anything like this. We were stationed in the Altstadt and it seemed as if all the Neustadt was on fire.”

Expecting an imminent attack, the garrison in the Neustadt prepared itself to repel the enemy. However, the Soviets attacked Kietz in a surprise attempt to take the suburb. After initial success, the Russians were stopped by a desperate counterattack that retook some of the ground lost earlier in the day, but leaving much of the southeast section of the town in enemy hands.

The following day Zherebin opened his assault on the Neustadt with troops from Dorofeev’s and Syzranov’s divisions. Garrison forces gave ground slowly, and by the end of the day the farthest Russian advance amounted to only about a kilometer.

The Neustadt attack continued the next day as Zherebin funneled more troops into the battle. Supported by tanks and the Red Air force, the attackers made steady progress, proceeding along the Friedrich-Wilhelm Canal and taking the cellulose factory by nightfall. Several other key positions were taken, and German engineers were ordered to blow up the Warthe bridges to prevent them from falling into Soviet hands.

The action effectively isolated the approximately 6,000 German troops that were still holding out in the Neustadt. Much of the blame was placed on the incompetence of Colonel Walther, who had totally lost command control of his troops.

Close quarter fighting in the Neustadt went on from March 9 to 12. The trapped German forces occupied strongpoints such as the infantry barracks and had to be blasted out by Soviet artillery and engineers. Because of the closeness of the attacking and defending forces and fears of hitting their own men, German artillery was extremely limited in its effectiveness. At the same time, much of the Red Army artillery shifted its bombardment to the Altstadt and Kietz.

The final battle in the Neustadt centered around the infantry barracks and another strongpoint, the Neues Werke, both of which were on the northeast side of the sector. On March 12 they were both taken, and Lt. Gen. Berzarin declared the area secure. The Russians reported taking 2,774 prisoners and claimed another 3,000 Germans killed.

Plans for the Battle of Berlin Finalized in Moscow

In Moscow, plans for the Battle of Berlin were being finalized. Zhukov had already met with Stalin in November 1944, when a preliminary plan was discussed. At that time Stalin seemed to agree that the 1st Belorussian Front would be picked to capture the German capital. However, as was his nature, he would later play Zhukov against Konev and his 1st Ukrainian Front for the honor of taking the city.

Zhukov was determined that he would arrive in Berlin first. To do that he needed to head down the highway that led from Küstrin to Berlin. A strong bridgehead would have to be established on the west bank of the Oder along the highway from which he could speed men and machines to the heart of the Reich. To do that, he needed to reduce the rest of Fortress Küstrin quickly.

A day after the Neustadt fell, Zhukov issued orders to take the Altstadt without delay. Zherebin’s 32nd Rifle Corps was to attack the Altstadt while Chuikov attacked the Kietz defenders with Lt. Gen. Vasili A. Glazunov’s 4th Guards Rifle Corps (35th, 47th, and 57th Guards Rifle Divisions). Both attacks failed to make any headway.

For the next nine days, Kietz and the Altstadt came under constant bombardment. Attacks by the 5th Shock and 8th Guards Armies, looking for weak points in the enemy defenses, also took place against German forces holding the narrow supply corridor.

On March 22, the Soviet infantry and supporting armor struck under the cover of massive artillery fire, with Zerebin attacking from the north with most of his corps, which had been sent to the bridgehead north of Küstrin, and Glazunov attacking from the south. Their goal was to cut the corridor in half, meeting just outside the village of Gorgast.

They would use the Soviet double envelopment tactic, which had been so successful at Stalingrad and in later battles. An inner ring would be formed midway between Kietz and Gorgast to trap enemy forces inside the picket with an outer ring formed east of Gorgast to fend off enemy attacks from the outside.

Manning the defenses in the intended area of the attack were elements of the “Doberitz” and “Muncheburg” Divisions. Under cover of the Red Army artillery, Dzhakhua’s 60th Guards Rifle Division hit the German defenses around Genschmar, a town northwest of Kietz. To Dzhakhua’s left, Dorofeev’s 295th Rifle Division punched through the enemy line and headed toward Golzow, a village west of Gogast. Along the Oder the 1373rd Regiment of Syzranov’s 416th Rifle Division worked its way behind elements of the 2nd Regiment “Muncheburg.”

On the southern flank of the corridor, Maj. Gen. Vasili M. Shugaev’s 47th Guards Rifle Division also pierced the German line and headed to meet Dorofeev’s division to create the outer ring. His left flank was protected by Colonel Petr I. Zalizivik’s 57th Guards Rifle Division. To his right, the 35th Guards Rifle Division pushed forward to hook up with the 1373rd, which would then form the inner ring of the encirclement.

After heavy fighting during which the Germans claimed 116 Soviet tanks destroyed, the outer pincers of the encirclement were closed that afternoon. Fighting continued on the 23rd as the Russians consolidated their newly won positions.

German counterattacks were thrown back with considerable loss to both sides during the next few days. In what remained of the Küstrin garrison, casualties mounted as the Red artillery continued to hammer the Altstadt and the Oder Island, which was nestled between the Oder River and the Vorlut Canal, and several German artillery positions were destroyed.

“The Altstadt was being pulverized,” Wüstenhagen recalled. “There were few buildings left standing and my gun company had taken several casualties.”

A Desperate and Failed German Counterattack

On March 27, the Germans launched a desperate counterattack to reopen the corridor. Unlike the previous efforts, this was to be a coordinated attack. General Theodor Busse, commander of the 9th Army, had been ordered by Berlin to gather a force that could break through to the Küstrin garrison. Under the nominal command of General Karl Decker, the force consisted of Burmeister’s 25th PGD and Colonel Georg Schulze’s 20th Panzergrenadier Division, Mummert’s “Munchenburg” Panzer Division, Brig. Gen. Hellmuth Mader’s “Führer-Grenadier-Division,” SS Lt. Col. Kurt Hartrampf’s Schwere Panzer Abteilung (schw. Pz. Abt.—heavy tank (Tiger) detachment about the size of a battalion), and a combat group under the command of Lt. Col. Gustav-Adolf Blanchbois, consisting of about 500 infantry and almost 50 “Hetzer” self-propelled antitank guns, that was named “1001 Nights.”

At 0400 the German forces moved forward. They ran into trouble almost immediately. During the previous three days Russian engineers were busy laying extensive minefields in front of their positions. In the north the “Muncheburg” Panzer, with “1001 Nights” on its right flank, headed toward Genschmar, which was defended by the 60th Guards Rifle Division. Under intense Soviet fire, the spearhead made it to the outskirts of the town before being driven back with heavy losses. The “1001 Nights” lost about two-thirds of its men either killed, wounded, or missing and half its Hetzers.

The center attacking force (“Führer-Grenadier-Division and a panzer and panzergrenadier battalion from the 20th PGD) broke through the lines of the 295th Rifle Division and headed toward the German forces trapped on the west bank of the Oder. They were also forced to turn back after receiving heavy artillery fire and a strong counterattack.

To the south, part of the 90th Panzergrenadier Rgt./20th PGD, Hartrampf’s Tigers, and the 25th PGD hit the 47th Guards Rifle Division. Their goal was Gorgast, but minefields and strong Soviet defensive positions at the main line stopped them cold. The experiences of schw. Pz. 502 were documented in Wolfgang Schneider’s book Tigers in Combat II.

“Shortly after crossing the line of departure, the 1./schw. Pz. Abt. 502 is stopped in a minefield. Three Tigers are immobilized. The same thing occurs in the attack sector of the 3./schw. Pz. Abt. 502, which is advancing on the right side of the main road (from) Manchnow to Kietz. One panzer, Tiger 321, is immobilized after running over a mine. It then knocks out two Soviet tanks before it is knocked out by a captured Panzerfaust.”

Accompanying engineers cleared a path through the minefield before sunrise, allowing the 1st and 2nd Companies to continue the attack. The Tigers destroyed four Soviet tanks before they were ordered to halt because they had lost contact with their accompanying infantry protection.

There were also other concerns. The 2nd Company’s acting commander, SS 2nd Lt. Schroif, was not up to the task. Schneider’s documented account continued: “The new commander of the 2./schw. Pz. Abt. 502 is unfit for the stress of combat and gets on the nerves of tank commanders by constantly issuing nonsensical orders. His tank gets stuck in a large bomb crater during a withdrawal movement. One after another, five Tigers are hit and are immobilized. After darkness falls the battalion moves back to Seelow. The operational panzers of the battalion assemble in Neu Tucheband. Operational panzers; 13.”

With Küstrin’s Fate Sealed, the Soviets Look on to Berlin

The failure of the attack had far-reaching consequences. Hitler was furious, and on the afternoon of March 28 he vented his anger on the unfortunate Busse, blaming him personally for the failure. While Hitler was berating Busse, General Guderian jumped to his defense.

“Permit me to interrupt you,” he said to Hitler. Barely controlling his own volatile anger he continued, “I explained to you yesterday thoroughly, both verbally and in writing, that General Busse is not to blame for the failure of the Küstrin attack. Ninth Army used the ammunition that had been allotted it. The troops did their duty. The unusually high casualty figures prove that. I therefore ask you not to make any accusations against Gerneral Busse.”

After the outburst, Hitler ordered the room to be cleared. Only Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Guderian remained behind. Hitler then ordered Guderian to take a six-week convalescent leave. Guderian would never see Hitler again.

The fate of Küstrin now seemed to be sealed. As the defenders around Kietz, on the island, and in the Altstadt heard the firing fade away to the west, groups of soldiers decided to take matters in their own hands and prepared to break out.

“When I heard about my men wanting to get out, I initially refused to let them go,” Wüstenhagen recalled. “We had received no such orders from our superiors, and our current orders were to hold at all costs. In later years I realized how idiotic that sounded. The next day (March 29) I came to my senses. We had no chance of holding the area, and an attempt to break out was preferable to a Soviet prison camp.”

Reinefarth apparently came to the same conclusion. On March 29, he asked Berlin for permission to break out. His request was refused, but Reinefarth had no illusions as to what his fate would be if he fell into Soviet hands. He too decided to take his chances and leave Küstrin.

In the final hour of March 29, the breakout began. After breaching the first Soviet line, the garrison forces found themselves in hand-to-hand night fighting as they moved toward the lines of the 9th Army. Having crossed the Oder, they were joined by the Kietz defenders. The situation was confused, and the Germans ran into fire not only from the Soviets, but from their own troops and artillery, which had no idea that a breakout was occurring.

Helped by the element of surprise, the darkness, and intermittent rain showers, the Küstrin survivors started trickling into the 9th Army line as dawn broke. Later that day, 9th Army headquarters reported that 32 officers and 956 NCOs and lower ranks had made it through. Other smaller groups continued to reach the German lines during the next few days. According to a Wehrmacht report, the attempt had cost 627 men killed and 2,359 wounded. Another 6,994 were listed as missing.

In the Altstadt there were still pockets of resistance, held by Germans who could not or would not evacuate their positions. They were systematically destroyed by the Soviets. By March 31, the entire fortress was in Russian hands. Zhukov now had his springboard to Berlin.

The survivors of the breakout were now in a kind of limbo. They were isolated and interrogated, not knowing whether they would be shot or hanged for disobeying a Führer Order or simply let go. However, Germany was collapsing, and they eventually were sent to other ad hoc units that were being formed to stop the coming Battle of Berlin.

Wüstenhagen recalled those final days. “From about 16,000 soldiers at the beginning of the Russian siege only 1,200 men could arrive [on] the German Oder Front after the town was extremely destroyed [sic] and the last ammunition was shot.”

“Myself, I did no more than my duty. I received the Knight’s Cross after the battle (On April 14—one of the last ones awarded). My comrade, Major (Emil) Hethy got with me the same decoration. I do not know whether he was fallen later on.”

Hethy commanded a combat group in the garrison and during the breakout. He did, in fact, survive the war and died in 1983.

“After new activities in the ‘Spreewald’ not very far from Berlin I was wounded once more and the Russians grabbed me,” Wüstenhagen continued. “I was brought into a Russian hospital at Zossen on 30 April. Tolerable [sic] cured, I could escape with civilian clothes brought by German inhabitants [along)] with bread and other things after the capitulation of May 8.”

“I crossed the big river, the Elbe, during the night with three other companions by swimming near the town of Dessau and I arrived at my family at Goslar safely after some days. After the war I began my studies at the school of forestry and I became a forest officer in the state forest.” Wüstenhagen died on April 8, 2008.

Reinefarth defended his actions in a report on the fall of the fortress and the breakout. In one excerpt he blamed garrison officers for his failure as he recounted a March 29 meeting. “The officers told me unanimously that they no longer had control over their men and the experience of the last few days had shown that neither encouragement no threatening with weapons would avail…. I told the individual officers and SS leaders that due to the lack of ammunition and the soldiers’ refusal to do their duty holding on to a few square meters was no longer possible. Thus, the Führer Order to hold the fortress to the last bullet had been fulfilled.”

During the last weeks of the war and in the years that followed, Reinefarth seemed to lead a charmed life. Despite being sentenced to death by a military court, he remained unmolested in command of his troops until the war ended.

Reinefarth was used by the Allies during the Nuremberg Trials, at which he testified against some other members of the SS. He was arrested for war crimes after the trials but was released by a Hamburg court because it decided that there was a lack of evidence that he had committed atrocities. Other German courts upheld that decision despite numerous Polish requests for his extradition.

In 1951 he was elected mayor of Westerland, a town on the Island of Sylt. He continued in politics and served as a member of the parliament of Schleswig-Holstein from 1962-1967. After that he pursued his career as a lawyer. He died in May 1979 at his home on Sylt.

German territory east of the Oder, including the Küstrin area, was given to Poland after the war. The Neustadt of Küstrin was rebuilt and is now known as Kostrzyn. Most of the Altstadt was destroyed and has never been rebuilt. The only sound in that area is the eerie whistling of the wind as it blows through the skeletal ruins of shattered homes and buildings. Today, it has the nickname “Pompeii on the Oder.”

Author Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front and a frequent contributor to WWII History. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.