By Michael E. Haskew

The White House was a somber place in the summer of 1862. The Civil War was in the midst of its second costly year, and the Union armies had yet to win a significant victory in the eastern theater. President Abraham Lincoln, still mourning the death of his 11-year-old son, Willie, earlier that year, sought desperately to find a general who could reverse the growing belief that Confederate arms, under the able leadership of General Robert E. Lee, were invincible.

The Peninsula Campaign had come to naught in July after the Confederates turned away Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac from the gates of the Confederate capital of Richmond in the costly Seven Days’ Battles. At the end of August, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia routed another Union army, under Maj. Gen. John Pope, at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Adding insult to injury, Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart had raided Pope’s very headquarters, carrying off the general’s dress coat.

Following the debacle at Second Bull Run, Lincoln turned again to McClellan, whose extreme timidity in the field was contrasted with his superb organizational skills and the enduring confidence of his men. Lincoln hoped against hope that McClellan would finally bring Lee to decisive battle and destroy the Army of Northern Virginia once and for all. On the political front, Lincoln felt that the war-weary North needed to be energized. He contemplated issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, a document that freed all slaves in the rebellious states. The proclamation, Lincoln hoped, would add a moral dimension to the war besides the preservation of the Union. He needed a legitimatizing Union victory in the field before he could issue the proclamation.

“We Cannot Afford to be Idle”

While Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were indeed triumphant, the Confederate commander realized all too well that his gains were temporary; he needed to undertake a bold stroke while the opportunity still presented itself. Lee knew that the capacity of the Union to wage war was virtually limitless. From his headquarters at Chantilly, Virginia, Lee wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis of his intent to carry the war to Northern soil. “The present seems the most propitious time since the commencement of the war for the Confederate Army to enter Maryland,” Lee noted. “We cannot afford to be idle.”

Strategically, Lee’s decision to invade the North made sense. For the first time since hostilities opened, Virginia was largely free of Union troops. Continued passivity would invite the Federals to return and once again mount an offensive against Richmond. Maryland was a border state and remained in the Union, but Lee believed that large numbers of Southern sympathizers would rally to his ranks once the Army of Northern Virginia entered the state. If successful in Maryland, the army might venture into Pennsylvania, destroy the vital Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge across the Susquehanna River, and threaten the state capital of Harrisburg. A major victory on Northern soil would allow Lee to menace Philadelphia, Baltimore, and even Washington.

On the diplomatic front, the Confederate cause was ripe for recognition by European powers, particularly Great Britain and France. The textile mills of Europe were dependent on Southern cotton for continuing operations, and the British government keenly felt the urgency to recognize the Confederacy. A military victory in the North, Lee reasoned, would all but assure recognition of the Confederate States of America as a sovereign nation. Following the Confederate triumph at Second Bull Run, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston had observed that the Union forces had received “a very complete smashing.” If Lee’s remarkable run of success continued, said Palmerston, “Would it not be time for us to consider whether in such a state of things England and France might not address the contending parties and recommend an arrangement on the basis of separation?”

Robert E. Lee’s Appeal to Marylanders

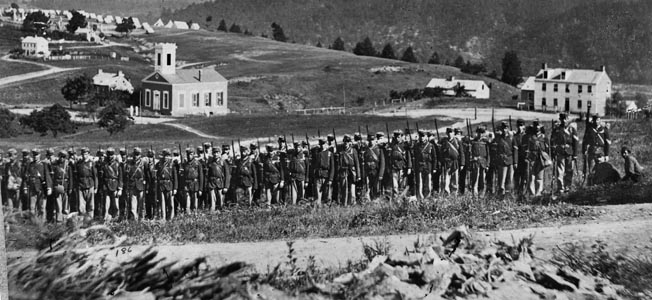

For all those reasons, the stakes were extremely high when the Army of Northern Virginia reached White’s Ford on the banks of the Potomac River on September 4 and 55,000 hungry troops stripped off their ragged clothes and began wading into Maryland. By the 7th, the army was completely across the Potomac and camped in the vicinity of Frederick. Lee issued a proclamation to the people of Maryland inviting them to join the Southern cause. “No constraint upon your free will is intended, no intimidation is allowed,” Lee promised. “Within the limits of this Army, at least, Marylanders shall once more enjoy their ancient freedom of thought and speech. We know no enemies among you, and will protect all of every opinion. It is for you to decide your destiny, freely and without constraint. This army will respect your choice whatever it may be.”

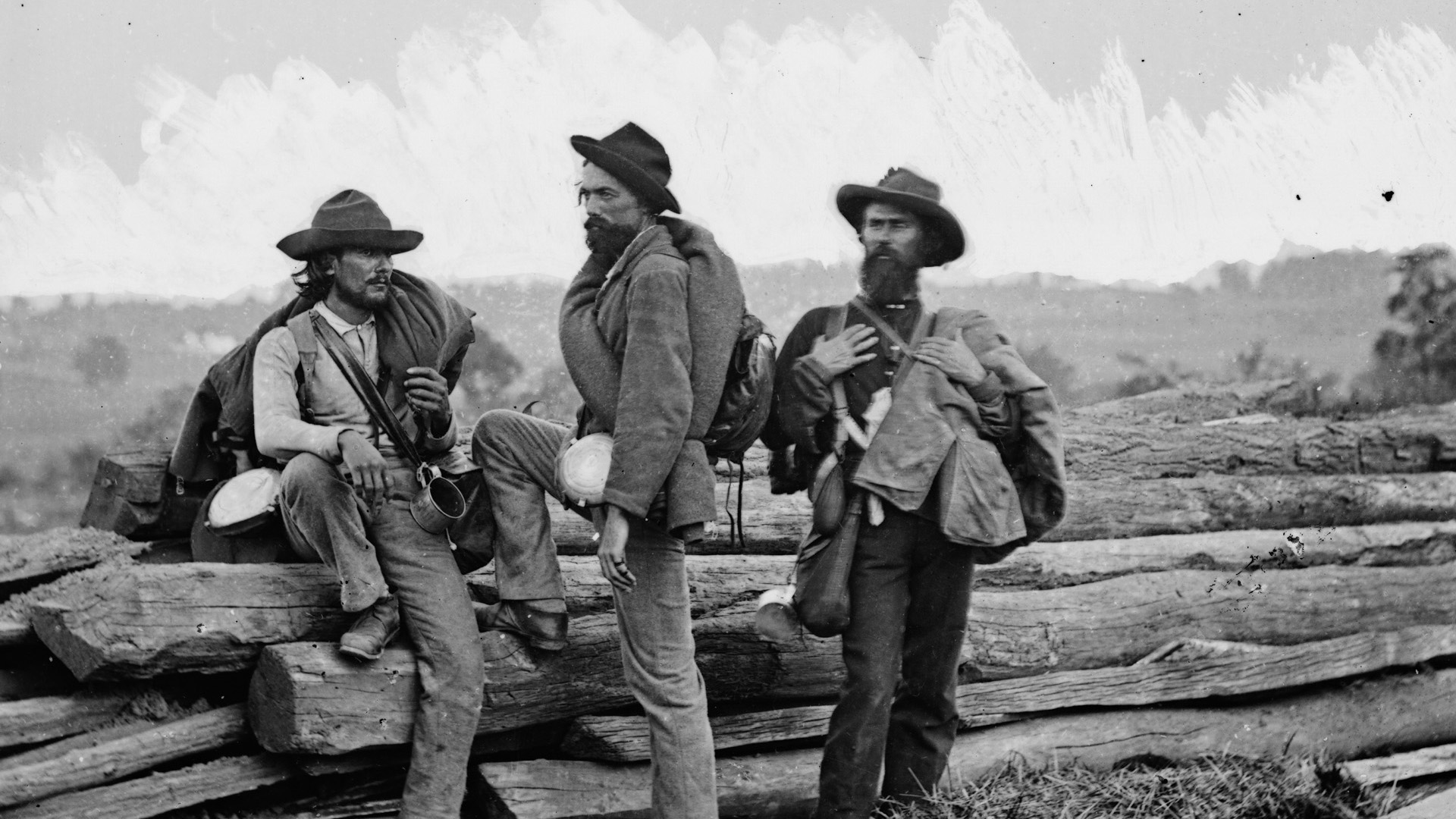

To Lee’s immediate disappointment, the citizens of Frederick generally kept their shops locked up tight. Western Maryland did not rally to the Stars and Bars. Marylanders were wary and observed the Confederates with a mixture of sympathy, awe, and disdain. Commented one civilian: “They were the dirtiest men I ever saw. A most ragged lean and hungry set of wolves.”

McClellan vs the Army of Northern Virginia

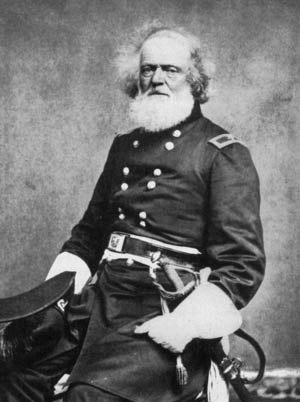

Meanwhile, on September 2, McClellan retook command of the army to the cheers of his men. In a superb organizational effort lasting just four days, he completed the assimilation of units from the former Army of Virginia into the Army of the Potomac. His orders from Lincoln and Army General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck were somewhat vague: protect Washington and, if possible, destroy Lee’s army in the process. The first reports of the Confederate move into Maryland arrived in Washington on the afternoon of September 4, prompting McClellan to begin moving at a deliberate pace from his encampment at Rockville, Maryland.

While his own numbers swelled to nearly 90,000, McClellan, ever cautious, was concerned about the strength of his enemy. Wildly exaggerated estimates of Lee’s numbers, ranging upwards of 200,000 men, filtered into McClellan’s command from unreliable civilian sources and from agents employed by private detective Allan Pinkerton, whom McClellan knew from their days together on the Illinois Central Railroad before the war. The exaggerated estimates played on McClellan’s natural tendency toward caution and contributed to his lack of aggressiveness.

By September 12, the Army of Northern Virginia expected to mass in the vicinity of Hagerstown, poised for the push into Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, Lee counted on McClellan’s lack of aggressiveness. Lee directed Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s three divisions to cross South Mountain, a ridgeline running north to south along the eastern edge of the Cumberland Valley, and proceed to Boonsboro, about halfway to Hagerstown. Detached from the command of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s division was to follow Longstreet as the army’s rear guard.

The remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia, divided into three separate commands, would converge on Harpers Ferry and compel the garrison to surrender. Swinging widely to the west, Jackson was to scoop up the enemy garrison at Martinsburg and move on to Harpers Ferry. Two divisions under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws were to approach the arsenal from the north and seize the commanding position of Maryland Heights. Moving due east, Brig. Gen. John Walker’s division was to recross the Potomac and capture Loudoun Heights on the Virginia side of Harpers Ferry. Stuart’s cavalry was to remain east of South Mountain, screening the movements from the enemy. Following the surrender of Harpers Ferry, the scattered Confederate forces would converge.

Lee detailed his complex plan in Special Orders No. 191, dated September 9. Colonel Robert H. Chilton, his adjutant, copied the orders for subordinate generals. When Lee’s order reached Jackson, he dutifully prepared another copy for Hill, his brother-in-law, unaware that Chilton had included Hill among those receiving the order directly from Lee. The next day, the Army of Northern Virginia set out from Frederick.

Special Orders No. 191

On the morning of the 13th, the 27th Indiana Infantry paused to rest in a field on the outskirts of Frederick. It was obvious to the Union veterans that the area had recently served as a Rebel bivouac. Corporal Barton W. Mitchell of Company F noticed something unusual lying in the grass. He retrieved an envelope that contained three cigars wrapped around the copy of Special Orders No. 191 that Chilton had intended for Hill. Apparently it never reached the general.

Mitchell took the document to Sergeant John M. Bloss, and the two took it to Captain Peter Kop, their company commander. Kop sent the order farther up the chain to Colonel Silas Colgrove, the commander of the 27th Indiana, who went directly to XII Corps headquarters, where Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams and Colonel Samuel Pittman read the document with great interest. Its authenticity was confirmed when Pittman noted Chilton’s signature and recognized the handwriting of Lee’s adjutant, with whom he had served before the war. Williams sent the order to McClellan with a note that read: “I enclose a Special Order of Gen. Lee commanding Rebel forces which was found on the field where my corps is encamped. It is a document of interest and is also thought genuine.”

When McClellan received the communication from Williams, he abruptly ended a conference with a delegation of citizens from Frederick. As he read, McClellan waved his arms and shouted, “Now I know what to do!” Later that day, McClellan visited with his old friend, Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, commander of the 4th Brigade, I Corps. “Here is a paper,” McClellan chirped, “with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home.”

Certainly McClellan’s opportunity was great. If the Army of the Potomac moved rapidly through the passes in South Mountain, which an overconfident Lee had failed to defend, McClellan might interpose superior forces between Longstreet to the north and Jackson, McLaws, and Walker to the south, take on the Rebel commands separately, and defeat them one at a time. McClellan talked of rapid movement and exhorted subordinates to prepare for the march. Typically, he waited until the morning of September 14 to get moving.

The Battle of South Mountain

Meanwhile, Lee was becoming anxious. Early reports from Stuart’s cavalry told him that McClellan was on the road to Frederick, and on September 10 he ordered Longstreet to advance to Hagerstown with 10,000 troops, occupying the village before any Union forces might contest the Confederate rallying point. Hill’s rear guard remained at Boonsboro with 5,000 troops.

By the evening of the 13th, it appeared to Lee that his risky plan was coming apart. Harpers Ferry was still in Union hands, and McClellan’s advance toward South Mountain was disturbing. Lee prodded Jackson and McLaws to wrap up their work at Harpers Ferry. At the same time, he began throwing together a patchwork defense of the South Mountain passes at Turner’s, Fox’s, and Crampton’s Gaps. Lee had no illusions of holding the gaps for an extended period, but any delay in the Union advance might allow the Army of Northern Virginia to escape destruction.

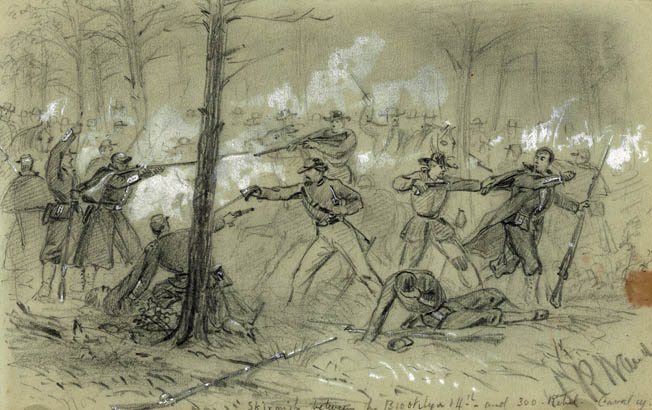

The Battle of South Mountain began early on September 14, and by 11 am Union troops of Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox’s Kanawha Division were in control of Fox’s Gap. Among the wounded during two hours of savage fighting was Lt. Col. Rutherford B. Hayes, commander of the 23rd Ohio Regiment and a future president of the United States. The Confederates lost one of their most promising brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland, mortally wounded just as he completed an assessment of the situation.

Hill forced Cox back to Fox’s Gap with a gritty, tooth-and-nail defense that included arming cooks, clerks, and teamsters. Late in the afternoon, reinforcements from Longstreet began to arrive. On the same ground where Garland had been killed earlier in the day, Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno, commander of the Union IX Corps, was shot. As he was carried to the rear, Reno yelled to Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis, one of his division commanders, “Hallo, Sam, I am dead!” Within minutes, Reno proved as good as his word.

Taking Harpers Ferry

As the sun was setting, the entire Union I Corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker advanced toward Turner’s Gap. Fighting raged into the gathering darkness as Georgia and Alabama troops under Brig. Gens. Alfred Colquitt and Robert Rodes fought desperately to hold the pass. Colquitt lost 100 casualties in an already understrength brigade, while Rodes faced two full Federal divisions, Brig. Gen. John Hatch’s 1st Division, I Corps, on his right, and the Pennsylvania Reserve Division under Brig. Gen. George G. Meade on his left. The avalanche of Union troops pushed Rodes steadily back and cost him more than one-third of his command. Reinforcements from Longstreet tried to stem the tide but were driven back. Only darkness halted the Union advance.

To the south, at Crampton’s Gap, a Confederate contingent of 1,000 men consisting of three Virginia infantry regiments and another from Georgia, two regiments of dismounted cavalry, and a few scattered guns of the horse artillery confronted more than 12,000 Union troops of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s VI Corps. One amazed Confederate artilleryman saw columns of enemy soldiers stretching into the distance and remarked that they were “so numerous that it looked as if they were creeping up out of the ground.”

The three-hour fight at Crampton’s Gap left 500 Union and 750 Confederate dead and wounded. When the Confederates withdrew, Franklin was only six miles from Harpers Ferry. McClellan had given him the option to push on to relieve the trapped garrison at the arsenal, but McLaws hastily put together a defensive line that gave Franklin pause. Eventually he decided against another general assault. His decision was pivotal. Had Franklin overwhelmed McLaws and marched hard for Harpers Ferry, he might have lifted the siege and checked any subsequent movement by Jackson.

Lee was left with few cards to play. It was obvious that Turner’s Gap could not be held, and he ordered Longstreet and Hill to withdraw to the west. To save his army from impending destruction, Lee decided to terminate the siege of Harpers Ferry and prepare for a general retirement across the Potomac to the safety of Virginia. Lee wrote to McLaws: “The day has gone against us and this army will go by Sharpsburg and cross the river. It is necessary for you to abandon your position tonight. Send forward officers to explore the way, ascertain the best crossing of the Potomac.”

The dejected Lee ordered Jackson to march to Shepherdstown to cover the withdrawal of Longstreet’s force. Lee had heard nothing from Stonewall and was startled to receive word a short time later that Harpers Ferry was expected to fall the next day. The delaying action at South Mountain, though costly, had given Jackson enough time to tighten his grip on the arsenal. As Longstreet’s men began trudging toward Sharpsburg, Lee reversed his earlier order. The siege of Harpers Ferry was to be successfully concluded as soon as possible.

Lee Readies His Stand in Maryland

Lee accompanied Longstreet’s columns across Antietam Creek, a tributary of the Potomac, heading toward the village of Sharpsburg. As the sun climbed into the sky on September 15, Lee surveyed a long, low ridgeline east of the town and asserted, “We will make our stand on those hills.” At noon he received confirmation from Jackson that Harpers Ferry had fallen and directed Stonewall to hurry to Sharpsburg, 12 miles to the north. Jackson in turn detailed Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill and his Light Division to take custody of 73 pieces of artillery and 13,000 rifles and revolvers and parole the prisoners at the arsenal. Meanwhile, Jackson got the remainder of his command on the road toward Sharpsburg.

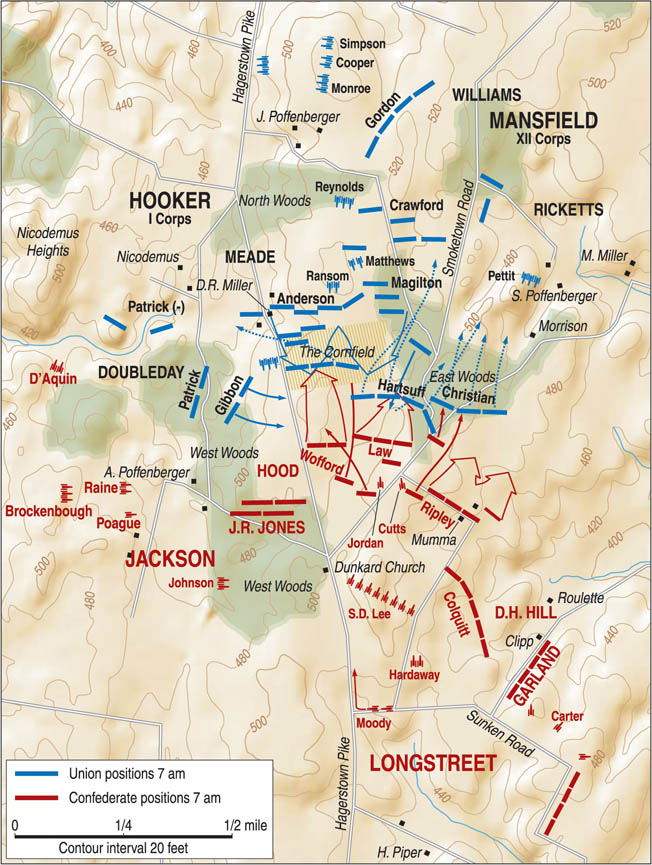

Over Longstreet’s objections, Lee deployed 18,000 men, 14 infantry and three cavalry brigades in a four-mile line across the woods and fields at the northern end of the ridge, down to the bluffs of Antietam Creek, where the southernmost of three stone bridges spanned its waters. Lee’s positions provided natural cover, with an undulating landscape and rocky limestone outcroppings, while west of the Hagerstown Turnpike the knoll known as Nicodemus Hill offered a commanding position for Confederate artillery. The terrain was dotted by farmsteads, pastures, and cornfields, separated here and there by rail fences. Although it offered some advantages, it was also precarious. Lee’s back was to the Potomac, and only Boteler’s Ford at Shepherdstown offered a clear avenue of escape across the river if the Confederates were driven from the field.

On the Confederate left, two brigades under Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood went into line on the fringe of the West Woods, a stretch of trees 300 yards wide to the west of the Hagerstown Turnpike, the major thoroughfare that led into Sharpsburg. Prominent in Hood’s defensive area was a plain, whitewashed church belonging to the German Baptist Brethren, a Christian sect that shunned anything ostentatious, including church steeples, and believed in baptism by full immersion. Locally, the members of the congregation were known as Dunkers.

About half a mile on the other side of the Hagerstown Turnpike, the East Woods flanked the Smoketown Road, which joined the turnpike at an acute angle. The North Woods stretched across the farmland of Joseph Poffenberger. East of the turnpike lay the prosperous farm of David R. Miller, including the house, outbuildings, orchard, and a 24-acre field of ripening corn, grown taller than a man’s head and nearly ready for harvest.

Stuart’s cavalry screened the Confederate left while D.H. Hill’s five brigades were funneled into the center of the Confederate line and filed into the sunken road. Brig. Gen. D.R. Jones covered the ground to the south and occupied the bluffs above the lower bridge across the Antietam with six brigades. Colonel Thomas Munford led a brigade of cavalry, bloodied from the fighting at South Mountain, to cover the fords south of the lower bridge.

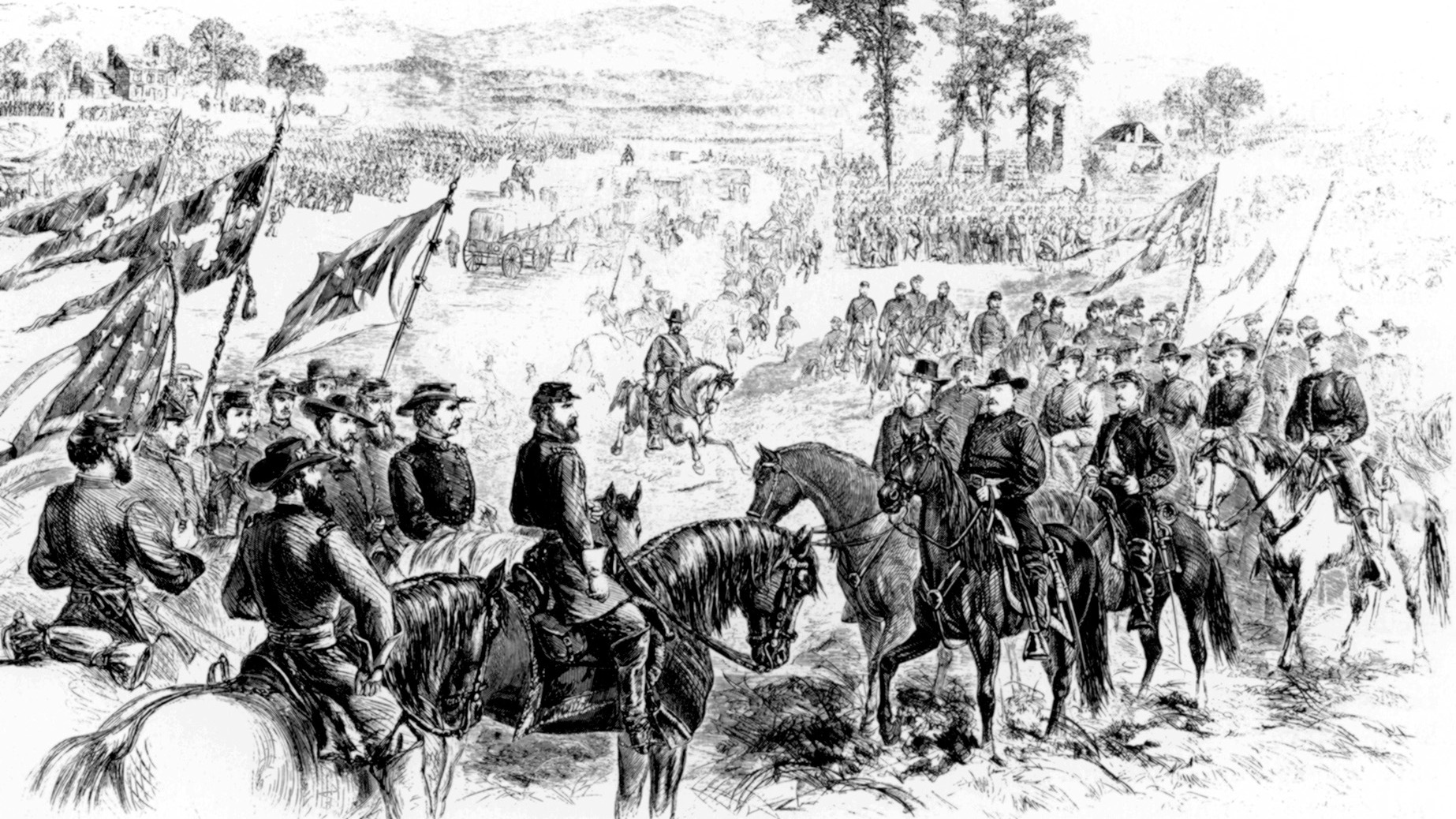

Lee, hopelessly outnumbered, still intended to make a stand in Maryland. He was convinced that the bulk of Jackson’s command, marching hard from Harpers Ferry, would reach the battlefield and swell his ranks to 50,000 men to confront McClellan’s force of 80,000. He also counted on McClellan to move slowly, which he did. Lieutenant James Wilson, a member of McClellan’s staff, observed, “Nobody seemed to be in a hurry. Corps and divisions moved as languidly to the places assigned them as if they were getting ready for a grand review instead of a decisive battle.”

The Army of the Potomac Crosses Antietam Creek

The first Union infantry formations did not arrive until the afternoon of September 15. The Army of the Potomac began to concentrate that night, but during the following day McClellan declined to make a decisive move. He tended to details while three of Jackson’s footsore divisions began trickling into the vicinity. About noon on the 16th, Jackson rode up to find Lee and Longstreet observing the Union troops across the creek.

McClellan deployed Hooker’s I Corps astride the Hagerstown Turnpike to the north. Running southward, XII Corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph K.F. Mansfield and II Corps under Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner extended the Federal right opposite Hood’s positions along the Smoketown Road to high ground near McClellan’s headquarters at a brick farmhouse. Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter’s V Corps occupied the Union center along the hills east of Antietam Creek, while Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside positioned his IX Corps opposite the lower bridge and the bluffs that commanded the approaches. Franklin’s VI Corps was held in reserve.

McClellan’s plan of attack depended on coordination and timing all along the line. It was finalized on the afternoon of the 16th, a full day after McClellan had arrived on the scene. McClellan charged Hooker and Mansfield, supported by Sumner, with the main effort against the Confederate left, while Burnside crossed the lower bridge and fords at Antietam Creek to attack the ridgeline on the Confederate right. If either effort made good progress, McClellan was prepared to pitch every available soldier against the center of Lee’s line.

Late on the afternoon of the 16th, Hooker crossed Antietam Creek intending to position more than 8,000 Union troops to launch the attack the following morning. Brig. Gen. George G. Meade’s 3rd Division led the way as flank protection, and one of its regiments, the 13th Pennsylvania, hearty deer hunters from the western woodlands known as the Bucktails, was hit particularly hard. Its commander, Colonel Hugh McNeil, was killed along with five others, and 20 were wounded. The fight began to peter out with the gathering darkness. Hooker threw a blanket on the ground near the Poffenberger farmhouse and commented within earshot of George Smalley, a reporter for the New York Tribune, “If they had let us start earlier, we might have finished tonight.”

A steady drizzle pelted down during the night, soaking the men as they fitfully slept. Occasionally, a nervous picket fired into the darkness. An hour before dawn, Hooker rode from the Poffenberger farm to his picket line beyond the edge of the North Woods. He surveyed the terrain and noticed a patch of high ground about a mile to his front near the junction of the Smoketown Road and the Hagerstown Turnpike. The little hillock would be his objective for the morning attack. To take it, Hooker’s divisions would advance along the turnpike between the East and West Woods, through the pastures of the Miller farm, and across the cornfield at the turnpike’s eastern edge.

Hood’s Confederates had been marching and fighting continually for several days, and Jackson gave permission for Hood to withdraw his division to the vicinity of the Dunker Church to cook rations. Jackson included the caveat that Hood be ready to move at a moment’s notice if called upon.

“Artillery Hell”

By 5:30 am, the morning fog had burned off enough for the Confederate horse artillery under Major John Pelham to fire at the Union vanguard from Nicodemus Hill. As Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday’s 1st Division marched through the North Woods, Gibbon’s 4th Brigade, wearing its distinctive black hats, led the way on the right. Gibbon’s command had fought with such ferocity at Turner’s Gap that Hooker commented that the men were as strong as iron. The troops began calling themselves the Iron Brigade.

Brigadier General David Ricketts’ 2nd Division, led by Brig. Gen. Abram Duryea’s 1st Brigade, stepped off to Gibbon’s left. The two brigades emerged from the North Woods simultaneously and crossed a field of clover. The Iron Brigade headed down the turnpike and into the northwest corner of the cornfield, while Duryea struck toward the East Woods and the cornfield’s southern edge. Meade’s 3rd Division followed in support.

The first Confederate shell struck the ranks of the 6th Wisconsin, killing two soldiers and wounding 11. As the Union troops came into view, more enemy guns under Colonel Stephen D. Lee, sited on the high ground opposite the Dunker Church, hit the attackers in their front. Nine Union batteries on the ridge behind the Poffenberger farm replied. Colonel Lee later described the fighting as “artillery hell.”

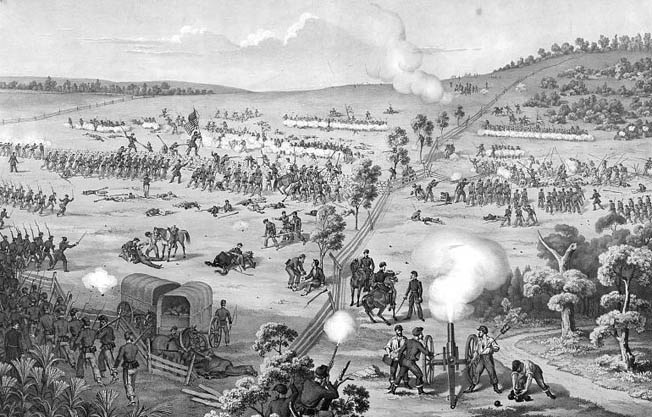

Bloody Clash in the Cornfield

While Hooker watched the opening moments of the fight from the Miller farm, he noticed that the cornfield was teeming with Rebels; bayonets gleamed in the morning sun above the ripening stalks of corn. Hooker ordered four batteries to unlimber. Their fire was devastating. In his later report, Hooker noted, “In the time that I am writing, every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battlefield.”

Under withering fire the Union vanguard pushed forward and the five Pennsylvania regiments of Meade’s 1st Brigade, under Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour, quickly reached the edge of the East Woods at the Smoketown Road. There they ran headlong into one of Lawton’s brigades under Colonel James A. Walker. These Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina troops stood fast and poured such deadly fire into the Pennsylvanians that they fell back to the cover of the trees.

Duryea’s brigade followed Seymour out of the East Woods and into the cornfield, stepping over mangled Confederate corpses that canister shots had killed moments earlier. The distance between the blue and gray lines was less than 250 yards. A brigade of Georgians under the command of Colonel Marcellus Douglass stood firm along the southern edge of the cornfield, reinforced by three regiments from Walker’s brigade. Over the next half hour, Douglass and half his command fell in the heated exchange of rifle and artillery fire. Walker lost 228 of his 700 soldiers and was forced to retire.

Duryea’s men fought valiantly, pressing the Georgians hard. In 20 minutes of fighting, Duryea lost 300 men. Ricketts’ remaining two brigades, under Colonel William A. Christian and Brig. Gen. George A. Hartsuff, moved forward. Hartsuff was wounded and Christian suffered an emotional breakdown and fled the field. The ensuing delay was costly, and before the brigades could rally it was too late to help Duryea.

While Douglass and Walker held on, Colonel Harry T. Hays’ hard-fighting Louisiana brigade, nicknamed the Louisiana Tigers, moved forward. Duryea’s battered brigade withdrew through the cornfield toward the East Woods, exposing the Iron Brigade’s left flank. The Tigers poured heavy fire into the 2nd and 6th Wisconsin, temporarily checking their advance. The Tigers also clashed with Ricketts’ brigade, under Colonel Richard Coulter, who had replaced the wounded Hartsuff, as the Federals rushed through the shattered cornfield. Firing canister at point-blank range, Union artillery raked the attackers.

After more than an hour of fighting around the East Woods and the eastern half of the cornfield, the Federals had failed to press their slight advantage, feeding troops into the battle piecemeal as the Confederates had rushed reinforcements from the center to stem the Union tide. Casualties were fearful. The Louisiana Tigers were reduced to fewer than 200 men after sending 500 into the battle. The 12th Massachusetts had 224 of its 334 soldiers shot down, a casualty rate of 67 percent that was the highest of any Union regiment on the field.

Captain Benjamin F. Cook of the 12th Massachusetts remembered the horrific fighting in the cornfield and its aftermath. “Rifles are shot to pieces in the hands of the soldiers, canteens and haversacks are riddled by bullets, the dead and wounded go down in scores,” he wrote. “The smoke and fog lift; and almost at our feet, concealed in a hollow behind a demolished fence, lies a rebel brigade pouring into our ranks the most deadly fire of the war. What there are left of us open on them with a cheer; and the next day, the burial parties put up a board in front of the position held by the Twelfth with the following inscription: ‘In this trench lie buried the colonel, the major, six line officers, and one hundred and forty men of the [13th] Georgia Regiment.’”

The West Woods

To the west, Doubleday’s division made better progress. Gibbon’s Iron Brigade plowed down the Hagerstown Turnpike toward the cornfield and the West Woods. After chasing Confederate skirmishers off the Miller farm, Gibbon’s men headed for the northwest corner of the cornfield and began taking fire from Douglass’ troops and the Stonewall Brigade posted in the West Woods.

The 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin crossed the turnpike to cover the Iron Brigade’s flank, and Gibbon brought up Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery to dislodge the Rebels to his front. The gunners went into action amid Miller’s haystacks, ignoring Confederate fire that cut down men and horses. Lt. Col. Edward Bragg of the 6th Wisconsin was wounded as the regiment was hit in both flanks. Major Rufus Dawes took command, pushing to a rail fence and engaging in a heated fight with Georgia troops south of the cornfield. Dawes remembered: “As we appeared at the edge of the cornfield, a long line of men in butternut and gray rose up from the ground. Simultaneously, the hostile battle lines opened a tremendous fire upon each other. Men, I cannot say fell; they were knocked out of the ranks by dozens.”

The 7th Wisconsin and 19th Indiana, moving as flank protection, fired a devastating volley into the two brigades assailing the 6th Wisconsin. The Confederates were hit from three sides and melted away while the Wisconsin soldiers, accompanied by the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters and the 14th Brooklyn, moved toward the high ground around the Dunker Church, still several hundred yards away.

As Jackson’s line wavered under unrelenting Union pressure, two brigades of his old division, 1,150 strong, rolled out of the West Woods. The division commander, John R. Jones, had been wounded by shrapnel earlier, and Brig. Gen. William E. Starke spurred his brigade of Louisiana soldiers and accompanying Virginians headlong into the Iron Brigade. Starke’s Louisiana men took up positions along a rail fence on the east side of the Hagerstown Turnpike. The distance closed to 30 yards, and the two sides blazed away at one another. The rail fence provided little protection, and Starke’s men fell in heaps. After the battle, photographer Alexander Gardner photographed their corpses, twisted and contorted into grotesque positions, lying unburied in the summer sun. Starke, shot three times, died on the field.

Doubleday Driven Back

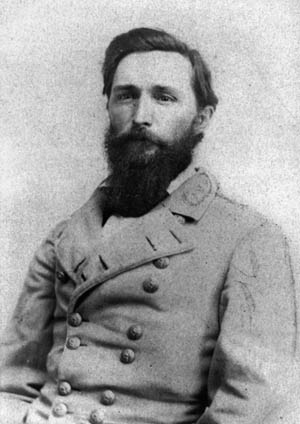

Despite heavy losses and tenacious resistance, Doubleday had driven deeply into Jackson’s line. A collapse of the Confederate left appeared imminent. Jackson summoned his last reserves, the 2,300 men of Hood’s division. Hood’s men threw down half-eaten biscuits and stuffed bacon into their mouths as they rushed to fill the gap. Hood, a Kentuckian, commanded a full division including his old brigade of the 1st, 4th, and 5th Texas, the 18th Georgia, Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s South Carolina Legion under the command of Colonel William T. Wofford, and a second brigade under Colonel Evander M. Law that consisted of the 4th Alabama, 2nd and 11th Mississippi, and the 6th North Carolina regiments.

Hood’s division roared out of the West Woods, around the Dunker Church, and through a gap in the fence along the Hagerstown Turnpike, pitching furiously into the Iron Brigade. The Union troops were thrown back as Wofford rolled into the western portion of the cornfield and Law struck to the east. Three brigades from Hill’s division supported Hood’s defenders, and Brig. Gen. Jubal Early’s brigade left Pelham’s horse artillery on Nicodemus Hill to join the fray.

As the reliable Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery blasted Hood’s Texans with double loads of canister, Gibbon moved in to personally direct the fire. The cannon fire literally blew men apart. One Union officer saw “an arm go 30 feet in the air and fall back again.” The fighting was desperate as the Confederate tide surged forward. Hood said to one of Jackson’s aides, “Tell General Jackson unless I get reinforcements I must be forced back, but I am going on while I can.”

Within minutes, Doubleday’s hard-won progress was completely reversed. Ricketts’ division was knocked out of the battle with 30 percent casualties, and it fell to Meade to patch a defensive line together. Lt. Col. Robert Anderson’s 3rd Brigade, four regiments of Pennsylvania Reserves, crouched low behind a rail fence at the northern end of the cornfield and waited.

“You Are Firing at Our Own Men!”

The 1st Texas, under Colonel P.A. Works, was hot on the heels of the fleeing Federals and outran the rest of Wofford’s brigade. Racing 150 yards ahead of the units on either side, the whooping Texans came within 30 yards of the Pennsylvanians, who rested their rifles on the lowest fence rails and fired a withering volley at the legs of the onrushing Rebels, shrouded in the thick smoke of battle. More Union troops joined in from across the turnpike, and the Texans were caught in a murderous crossfire. Nine regimental color bearers were killed, and in less than half an hour the 1st Texas lost 186 dead and wounded, more than 82 percent of its strength, the highest casualty rate of any regiment on either side during the entire war.

Hood’s lightning counterattack prevented the collapse of the Confederate left and forced Hooker’s corps back essentially to its early morning starting point with more than 2,500 casualties. Hood, however, was unable to consolidate his gains. His division had suffered 1,380 dead and wounded, about 60 percent of its strength, and was forced to withdraw to the West Woods. Hood was aghast at the losses. When another officer asked the whereabouts of his division, he replied sorrowfully, “Dead on the field.”

During the course of the morning, the cornfield, a space 250 yards long and 400 yards wide, changed hands 15 times. The ordeal on the Confederate left was not yet over. At the sound of guns to their right, Mansfield’s 7,200-strong XII Corps, half of whom had never fired a shot in anger, set out at a leisurely pace, often allowed to break ranks and boil coffee. Fearful that his untried troops would break and run, Mansfield countermanded an order to deploy from columns into line of battle, and the massed ranks became a prime target for Confederate artillery.

Spotting Mansfield’s tightly packed troops, Hood’s men fired on the 10th Maine Regiment. When the Union men loosed a volley in reply, Mansfield, who had only taken command two days earlier, became confused, believing that large numbers of Federal troops were still to their front. “You are firing at our own men!” he shouted. Sergeant E.J. Libby remembered a loud response from the Maine men to the contrary. “Thomas Wait and myself told him that we were not firing at our own men for those that were firing at us from behind the trees had been firing at us from the first,” recalled Libby. Mansfield spluttered, “Yes, yes, you are right.” Precisely at that moment a bullet hit the 58-year-old general squarely in the chest. Mansfield was carried from the field and died within hours.

Williams took command of XII Corps and the fight for the cornfield continued, with men from both sides tripping over the dead and falling bleeding among the severed cornstalks. Among the wounded were Sergeant Bloss and Corporal Mitchell, who had found Lee’s lost orders four days earlier. Their company commander, Captain Kop, was killed.

“The Most Unutterable Stampede Occurred.”

Meanwhile, Colonel D.K. McRae’s North Carolina troops advanced into the East Woods. One of his junior officers observed a large Union formation moving to the right. Fearful that the brigade was about to be flanked, he raised the alarm prematurely. A wave of panic gripped McRae’s men, who turned and fled, causing the remnants of Hood’s brigades to fall back as well. McRae remembered: “The most unutterable stampede occurred. It was one of those marvelous flights that beggar explanation or description.”

The Union formation that panicked the Confederates in the East Woods was Mansfield’s 2nd Division under 61-year-old Brig. Gen. George S. Greene, a descendant of Revolutionary War General Nathanael Greene. The 28th Pennsylvania and 5th, 7th, and 66th Ohio of Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale’s 1st Brigade led the way. The Pennsylvanians fired a tremendous volley into the flank of Colquitt’s brigade, already locked in heavy combat with Union troops in the clover pasture beyond the northern fringe of the cornfield. Tyndale’s men charged into the cornfield, and several minutes of hand-to-hand fighting ensued before the Confederates began withdrawing toward the West Woods. The carnage was terrific; only two dozen of the original 250 men of the 6th Georgia survived the maelstrom without being killed or wounded.

Two divisions of Sumner’s corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. William French and Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, crossed Antietam Creek to support Mansfield. The divisions became separated, and Sedgwick pressed forward with 5,000 men through the northern edge of the West Woods, coming under heavy attack from elements of three Confederate divisions and Pelham’s horse artillery on Nicodemus Hill. The decimated survivors retreated in disorder, leaving behind 2,200 killed and wounded.

Greene’s 2nd Brigade, under Colonel Henry J. Stainrook, reached the Smoketown Road and unhinged the Confederate right flank. Hill worked feverishly to extricate his battered brigades, while the 102nd New York Regiment drove relentlessly toward the high ground around the Dunker Church, where Colonel Lee’s artillerymen were doing their best to limber their guns and retire. Greene rode forward and warned the New Yorkers to slow down before they outran covering artillery. “Halt, 102nd,” he ordered. “You are bully boys but don’t go any farther. Halt where you are. I will have a battery here to help you.”

A Battle Far From Won

Greene’s two brigades were within 200 yards of the Dunker Church, where they halted and watched the West Woods swarm with Confederates. Hooker, conspicuously mounted on a white charger, rode to the southern edge of the cornfield and saw an opportunity to rally the remains of his corps, bring artillery forward, and join with XII Corps to strike the decisive blow. Just then, an enemy sharpshooter put a bullet through Hooker’s foot, which bled profusely. Unable to remain in command, he left the scene convinced that Union forces were poised to drive the Confederates into the Potomac. “I supposed that we had everything in our own hands,” he thought.

The situation was not as promising as Hooker had hoped. XII Corps had lost a quarter of its men during the rush across the cornfield toward the Dunker Church. Stragglers were everywhere, and entire regiments milled about without direction. Commanders on both sides were trying to make order out of chaos, and even the most hardened veteran could scarcely comprehend the unimaginable holocaust that engulfed the cornfield, the woods, turnpike, and high ground around the Dunker Church, where more than 8,000 soldiers, Union and Confederate, lay dead or wounded.

One soldier of the 6th Wisconsin captured the essence of that horrific morning. The fighting, he said, was like “a great tumbling together of all heaven and earth—the slaughter on both sides was enormous.” By 10 am, the opening phase of the battle had blown itself out, and the fighting swung southward. America’s bloodiest day was far from over.

Excellent summaries of the individual skirmishes and the overall battle. I lived there as a child and these were the fields we played in before they became National Park Service protectorates, the mid-1950s. Great job.

I’m glad that the map correctly shows the “Dunkard” Church, after that particular sect of German Baptists. Most of the time it’s misspelled.

THANKS FOR SHARING. VERY INTERESTING.