By Colonel Dick Camp (USMC, Ret.)

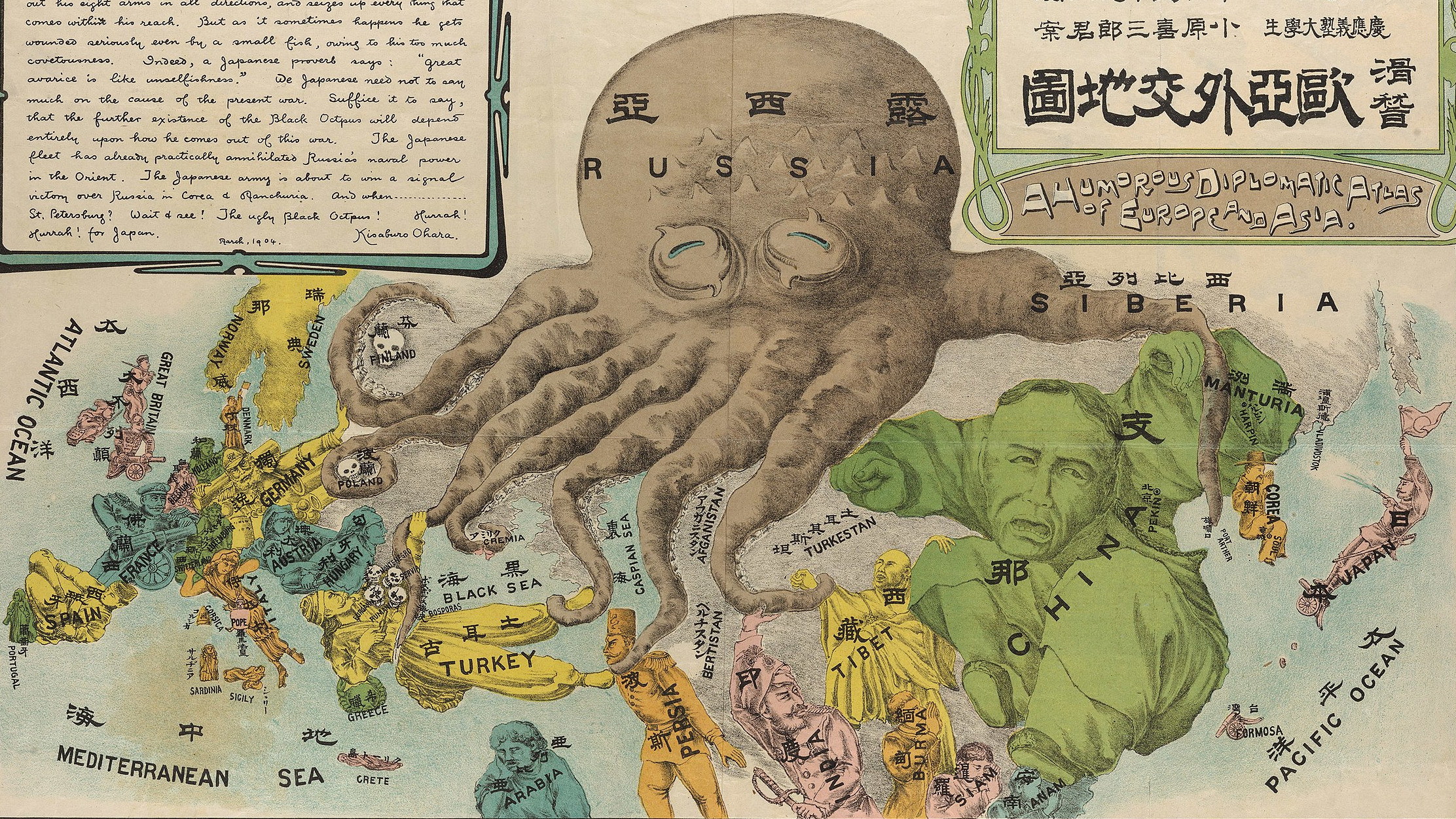

In the summer of 1944, the 5th Amphibious Corps under Marine Lt. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin Mad” Smith set its sights on the Japanese-held island of Saipan in the Mariana Islands, one of the “Islands of Mystery,” as its next objective.

Brig. Gen. Merritt A. Edson, Assistant Division Commander, 2nd Marine Division, remarked, “This one isn’t going to be easy.” Smith echoed his comment. “We are through with the flat atolls now. We learned how to pulverize atolls, but now we are up against mountains and caves where the Japs can dig in. A week from today there will be a lot of dead Marines.”

The capture of the island, designated Operation Tearaway, would firmly establish U.S. forces within Japan’s inner defense line. Smith stated that the United States needed air bases “to initiate very long-range air attacks on Japan.”

Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo, commander of the Japanese Central Pacific Fleet Headquarters, concurred. “The Marianas are the first line of defense for the home island,” he said. (Nagumo had led the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. He would commit suicide on Saipan, July 6, 1944.)

General Smith’s force, designated the Northern Attack Force (Task Force 52), would have two veteran Marine Divisions—the 2nd, (2nd MarDiv), commanded by Maj. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, and the 4th (4th MarDiv), commanded by Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt—with the Army’s 27th Infantry Division (27th ID), commanded by Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith, in reserve. Altogether, the 5th Amphibious Corps comprised 71,000 soldiers and Marines.

Saipan was defended by the 1st Expeditionary Force, an estimated 25,000-to-30,000 Japanese, including 5,000 sailors of the 5th Special Base Force, 1st Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force (mistakenly referred to as Japanese Marines), the 55th Naval Guard Force, and the 9th Tank Regiment, consisting of four companies equipped with 12 Type 95 Ha-Go light tanks and 35 Type 97 Kai Shinhoto Chi-Ha medium tanks. General Smith remarked, “It was the most heavily garrisoned island in the Marianas.”

The defense of the island was based on the Japanese doctrine of “destroying the enemy at the beaches” during the buildup of forces, when the invasion force was most vulnerable and before they could gain a foothold ashore. A captured Japanese document read: “It is expected that the enemy will be destroyed on the beaches through a policy of tactical command based on aggressiveness, determination, and initiative.” The battle order stated, “Seven Lives To Repay Our Country.” The phrase meant that each Japanese soldier pledged to kill seven Americans before he died.

Lt. Gen. Yoshitsugu Saito commanded the Japanese forces. His two major organizations were the 43rd Division (reinforced), composed of three infantry regiments (118th, 135th [less 1st Battalion], and the 136th) and additional transportation, medical, ordnance and communication units; and the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade, commanded by Colonel Yoshiro Oka, comprising three independent infantry battalions (316th, 317th and 318th).

In May 1944, the Japanese changed their system of nomenclature. Infantry personnel were organized into “independent infantry battalions” and numbered consecutively. The battalions then became part of “independent mixed brigades,” to which were attached one or more battalions of artillery and an engineering company or antiaircraft unit, or both. `These brigades were, in turn, assigned numbers.

The Japanese divided Saipan into four defense sectors: Northern sector (135th Infantry Regiment) included the northern third of the island; Navy sector (5th Special Base Force; Central sector (136th `Infantry Regiment); and Southern sector (47th Independent Mixed Brigade).

Additional units were located at Chacha-Tsutsuuran area (four infantry companies in reserve), Mt. Fina Susu (one battalion of field artillery), Chacha-Laulau area (9th Tank Regiment), and Aslito Airfield (antiaircraft artillery).

Preparatory bombardment for Saipan was limited to carrier and surface strikes by Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 58—55 ships (11 battleships, five cruisers, 15 destroyers, and 24 LCI gunboats (LCI (G)—beginning on D minus 4.

Their primary targets were coast defense guns, antiaircraft batteries, artillery weapons, and other enemy defenses and personnel. At dawn on D-Day (June 15, 1944), naval gunfire was directed at the landing beaches, known and suspected positions of enemy coast-defense guns, and antiaircraft and field-artillery batteries.

An NCO of the 43rd Division, Squad Leader Yamauchi Takeo, remarked, “I was eating a large rice ball when I heard a voice call out, ‘The American battle fleet is here!’ I looked up and saw the sea completely black with them. Then the naval bombardment began. The first salvo exploded along the beach and objects suddenly went 60 meters straight up! The area was pitted like the craters of the moon. We clung to the earth in our shallow trenches and were half buried. Soil filled my mouth and blinded me. The fumes and flying dirt almost choked you. The next moment I might get it.”

Concentrated aerial bombardment had begun two days before the landing, although occasional bombing had occurred for several months. On D minus 2, planes from the fast carrier force made fighter sweeps on Aslito airfield to destroy enemy aircraft and to deliver counterbattery fire on Japanese artillery firing on U.S. minesweepers.

“Suddenly antiaircraft artillery began to blast away,” Yamauchi described. “I looked up. Right in front of my eyes appeared huge numbers of American planes, and the air attack started.”

On D minus 1, inland coast defense and antiaircraft guns were heavily bombed. Cane fields not already burned were to be incinerated. Other priority targets were inland defense installations and structures; the buildings around Aslito airfield; and the communications and transportation facilities on the west coast of Saipan, including small craft, radio stations, observation towers, railroad and road junctions, and vehicles. Six smoke planes were to provide protection for underwater demolition teams operating close offshore, if necessary.

A Japanese NCO noted in his captured diary, “I was awakened by the air raid alarm and immediately led all men into the trench. Scores of enemy Grumman fighters began strafing and bombing Aslito airfield. For about two hours, the enemy planes ran amuck and finally left leisurely amidst the inaccurate antiaircraft fire. All we could do was watch helplessly.”

On D-Day, air and naval gunfire were integrated into a carefully choreographed bombardment of the Japanese defenses. At 5:30 am, the gunfire ships opened up, concentrating on the landing beaches and enemy positions that could interfere with the landing.

A Japanese soldier recounted the bombardment: “The din robbed us totally of all sense of hearing. It wasn’t the same as a boom or a roar that splits the ear; it was more like being imprisoned inside a huge metal drum that was incessantly and insufferably beaten with a thousand iron hammers.”

Another soldier remarked, “Extreme intensity of those flashes and boiling clouds of smoke…the area I was in was pitted like the craters of the moon. We just clung to the earth in our shallow trenches…half buried.”

The author of The Fourth Marine Division in World War II noted, “The towns of Garapan and Charan-Kanoa lay in smoking ruins, and the big sugar mill north of Charan-Kanoa loomed like a giant blackened skeleton against the pink summer sky.”

Richard G. Peterson, a member of Company D, 2nd Amtrac Battalion, recalled, “Many of us watching the shells explode in the dark all over Saipan thought that nothing could survive that pounding, so we felt relief that our job going in would be easy. `But those Marines who had been on Tarawa (November 20-23, 1943) knew a whole lot better.”

At 7 am, the ships lifted their fire for 30 minutes to allow carrier planes to bomb and strafe. Just before the scheduled landing, 24 LCI gunboats, equipped with rockets and 20mm and 40mm guns, moved in to pepper the beaches in an effort to prevent the enemy from firing on the landing craft.

Lt. Gen. Smith noted in his final report of the operation, “Naval gunfire support was a decisive factor in the conduct of operations,” while Rear Adm. Harry W. Hill, commander of the Western Landing Group wrote, “There can be little doubt that naval gunfire is the most feared and most effective of all weapons [with] which the Japanese are confronted in resisting a landing and assault. Without exception, POWs stated that naval gunfire…was the most deciding factor in accomplishing their defeat.”

Several years later, General Smith changed his mind. “Three-and-a-half days of surface and air bombardment were not enough to neutralize an enemy of the strength we found on Saipan.”

This would not be last time that Marines complained that the Navy’s gunfire support was inadequate: Iwo Jima was allocated only three day of preliminary bombardment after the Marines requested 10 days.

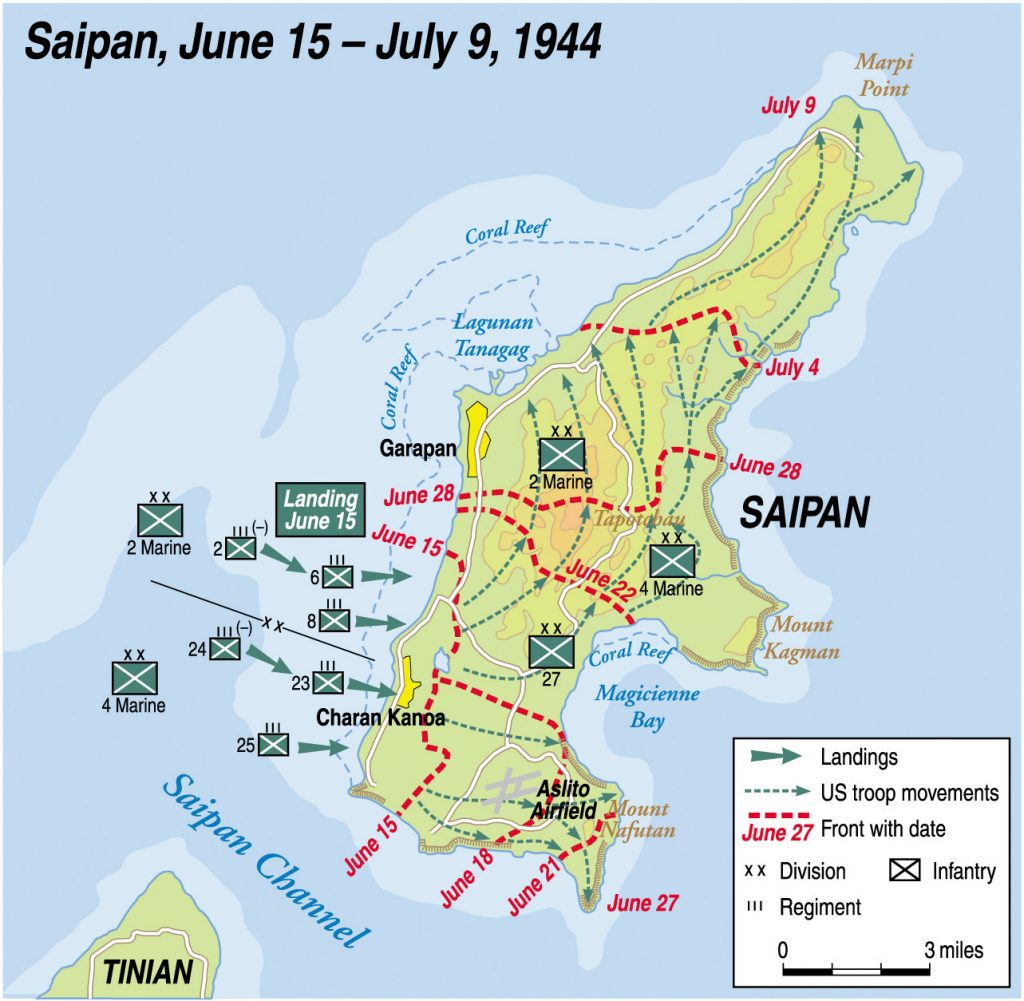

The scheme of maneuver for Operation Tearaway called for an amphibious landing on June 15, 1944, by the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. They were to land abreast over the western reef on beaches adjacent to the sugar-refinery village of Charan Kanoa and on both sides of Afetna Point—4th MarDiv on the right (Blue and Yellow Beaches) and the 2nd MarDiv on the left (Green and Red Beaches).

The 2nd MarDiv was to attack northeast and capture Mt. Tapotchau, while the 4th MarDiv was to attack to the southeast and seize Aslito airfield. Then, with the force beachhead line secured, the attack was to continue with the two divisions abreast to the north and northeast to secure the remainder of Saipan.

The landing plan envisioned eight Battalion Landing Teams simultaneously crossing a reef spanning 250 to 700 yards across. Eight thousand men were expected to land abreast in the first 20 minutes on seven of Saipan’s 11 designated landing beaches—Red 1, 2, and 3, Green 1, 2, and 3; Blue 1 and 2; and Yellow 1, 2, and 3—covering a front of 6,000 yards.

A diversionary demonstration off the beaches northwest of Tanapag Harbor, lasting from half an hour before sunrise to an hour after the main landing, was conducted by Marines of the 2nd Regimental Combat Team and the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines. Their landing craft went in as far as 5,000 yards off the beach, circled for 10 minutes, then and returned to their transports.

Howlin’ Mad Smith said, “Our landing was the most advanced mechanical demonstration we had ever made in the Pacific. We had 800 amphibious vehicles—troop carrying tractors (LVT)—tanks armed with 75mm howitzers and 37mm guns (LVT(A)-4), and the new LVT (4)s, a model with a back-dropping ramp that unloaded our artillery directly ashore.”

H-hour was initially set for 8:30 am but was pushed back 10 minutes to give the boat waves additional time to get into position.

At 5:42 am, Vice Admiral Richard K. “Terrible” Turner, Commander, Northern Attack Force, gave the command, “Land the Landing Force.” `This time-honored order was transmitted to the 34-ship Landing Ship Tanks (LST) flotilla located 1,250 yards behind the line of departure.

“The [bow] doors opened,” Marine Marshall E. Harris recalled. “Suddenly we faced Saipan then clattered down the LST’s metal ramp toward the sea….” Hundreds of armored amphibian tanks (known by the crews as amtanks) and amphibian tractors (amtracs) crawled into the water and commenced to circle, while waiting for the signal to go in from the Navy Control Boats.

Robert E. Wollin rode in an armored amphibian: “Our job [was to] lead the 1st wave onto Green and Red Beaches, clearing the enemy off those beaches and then push 200 yards inland so Marine infantry coming behind us could cross the beaches intact.” At 8:13 am, the signal was given, and 96 amphibious tractors (LVTs) carrying the assault units of the 2nd and 4th Divisions started for the landing beaches.

At 7:40 am, two Landing Ship Docks (LSDs) began launching LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized) loaded with light and medium tanks of the 2nd and 4th Tank Battalions. The LCMs proceeded smoothly to their assigned stations at the rear of each division’s beach. The tanks were in an “on call” wave, meaning they would be directed to land on order of the supported unit commander.

The peculiar construction of the LSDs was designed to transport loaded landing craft, ballast down to their well decks, lower the stern gate to the sea, and disembark their craft and vehicles for the assault on a hostile beach.

The 4th MarDiv’s landing beaches, color-coded Blue 1 and Blue 2 (23rd Marines Regimental Combat Team) and Yellow 1 and Yellow 2 (25th Marines Regimental Combat Team), were located on the lower west coast of Saipan, adjacent to the 2nd MarDiv’s landing beaches, Green 1 and 2 (8th Marines Regimental Combat Team) and Red 1 and 2 (6th Marines Regimental Combat Team).

The first wave consisted of 68 armored amphibians, armed with 37mm and 75mm guns, formed in line abreast. Behind them surged 196 troop-carrying amphibious tractors in four successive waves, spaced from two to six minutes apart. `

The first wave approached the fringing reef in good order. Charles H. Orloski was driving one of the amphibian tanks: “Coming to the reef, I waited for a wave to lift us up onto the coral, then I shifted as we rode the wave and got across and off it quite well.”

Robert E. Wollin recounted, “We got no Japanese fire outside the reef. Moving over the reef I saw small colored flags sticking out of the water. The Japs drove in aiming stakes overnight for their artillery waiting for us to come into range. Then all hell broke loose….” Mortars, small arms, and artillery fire increased in intensity.

Jerry D. Brooks recalled, “In the lagoon, hitting coral heads, bouncing us up down and sideways, it was impossible to shoot our 75mm howitzer with accuracy. A couple of our 75mm shells exploded directly in front of us. Two or three went nearly vertical … but our noise and the sight of us alone apparently made a big impression on the enemy. Naval operators monitoring Jap radio traffic picked up their radio messages telling Tokyo that ‘Monster Guns’ mounted on ‘Monster Floating Tanks’ were coming at them in the leading assault waves. Our 75mm’s muzzle with blast shield looked like an 8-inch gun.”

“Nearing the beach I saw a watery explosion then another and another,” Winton W. Carter recalled. “Ahead, slightly to my left, two men got up and started running inland. I stared. Paralyzed. I tried to grasp what this meant. They wore steel helmets, short sleeve shirts. ‘They’re Japanese, you Lummox, the enemy, shoot!’ It seemed ages. But probably two or three seconds actually passed until my brain and hands got to working together. Then I opened up with my machine gun, firing away.”

Wollin, in his armored amphibian, recalled, “Jap artillery was still bracketing us, trying to get our range, and drenching us with near misses, splashing water into open turret hatches. Still they were misses. We were lucky. As the Japs sharpened their range, the assault wave coming in behind us looked to be having the harder time.”

General Smith remarked, “Saipan instantly became a savage battle of annihilation … spearheaded by armored amphibian tractors…the Marines hit the beach at 0843…the best we could do was get a toehold and hang on. And this is what we did, just hang on for the first critical day.”

M. Neil Mumford described coming ashore: “I saw out the side hatch an amtank afire next to us, its hatch going up and down. I thought someone was trying to get out but the heat was moving the hatch, making it flutter, then the tank’s ammo began to blow. A shell hit the base of our turret. We abandoned our tank, only to discover it was safer inside.”

Squad Leader Yamauchi Takeo watched as the leading waves of troops landed and debarked—short of the O-1 line, the first day’s objective. “Someone shouted, ‘The American Army’s coming!” Yamauchi said. “I lifted my head a little. They advanced like a swarm of grasshoppers. The American soldiers were all soaked … they were so tiny wading ashore. I saw flames shooting up from American tanks, hit by Japanese fire.”

Long-range grazing fire from Japanese machine guns from Afetna and Agingan Points pelted the beaches, pinning the Marines to a shallow beachhead. First Lieutenant John C. Chapin recalled, “All around us was the chaotic debris of bitter combat. Jap and Marine bodies lying in mangled and grotesque positions; blasted and burnt-out pillboxes, the burning wrecks of LVTs that had been knocked out by Jap high-velocity fire; the acrid smell of high explosives; the shattered trees; and the churned-up sand littered with discarded equipment … suddenly—WHAM!

“A shell hit right on top of us! I was too surprised to think, but instinctively all of us hit the deck and began to spread out. Then the shells really began to pour down on us: ahead, behind, on both sides, and right in our midst. They would come rocketing down with a freight-train roar and then explode with a deafening cataclysm that is beyond description.”

The assault companies found themselves fighting for every inch. “Our attention [was] concentrated on our yard-by-yard advance inland—our beachhead was only a dozen yards deep at one point,” Holland Smith said. Another officer recalled, “It’s hard to dig a hole when you’re lying on your stomach digging with your chin, your elbows, your knees, and your toes, [but] it is possible to dig a hole that way, I found.”

Journalist Robert Sherrod wrote, “An artillery or mortar shell … landed every three seconds for the first 20 minutes. Most of them were in the water, 100 yards and more offshore, but some of them hit the beach itself. None of them hit inside the seven-foot deep [tank] trap which the Japs had built for their protection and which we were now using for our protection.

“Inside the trap, the battalion aid station for 2/8 (Lieutenant Colonel H. P. Crowe) had been set up. There were a half-dozen men lying on the sand; they were already wearing bloody bandages and awaiting evacuation by amtracs…in the 300 yards separating two [wrecked] vehicles I counted 17 dead Marines….”

Captain John A. MacGruder spotted “a young, fair-haired private who had only recently arrived as a replacement, full of exuberance at finally being a full-fledged Marine on the battle front. As I looked down at [his body], I saw something I shall never forget. Sticking from his back trouser pocket was a yellow pocket edition of a book he had evidently been reading in his spare moments. Only the title was visible—Our Hearts Were Young and Gay.”

Casualties sustained during the landing far exceeded 2,000; in the 2nd Division alone, 553 men were killed and 1,022 wounded. Out of the 68 armored amphibians, 31 were sunk or disabled. Five of the original infantry battalion commanders in the two divisions were wounded on D-day. Howlin’ Mad said, “Not for another three days could it be said that we had ‘secured’ our beachhead. We were under terrific pressure all the time.”

Shortly before noon, tank support was requested. Major Richard K. Schmidt’s 4th Tank Battalion, equipped with 46 freshly delivered M4A2 Sherman medium tanks and 18 M3A1 Satan flame-thrower tanks, mounting the Canadian Ronson flame gun, was tasked to support the assault battalions of the 4th MarDiv.

Company A, led by 1st Lt. Stephen Horton, Jr., with the 1st Platoon of Company D, was attached to Regimental Combat Team 25 (RCT-25). The operation plan called for the company to land over Yellow Beach 2; however, the company actually landed on Blue Beach 2 because of a strong northerly current. Company B, commanded by 1st Lt. Roger F. Seasholtz, was attached to Battalion Landing Team (BLT 3-23) and scheduled to land over Blue Beach 1.

Company C, commanded by Major Robert M. Neiman, was attached to BLT 2-23, 4th Mardiv, and was scheduled to land over Blue Beach 2. Company D, Captain Gorman T. Webb’s “Satans” landed over the Blue Beach throughout the day and was designated to support RCT-23.

Headquarters and Service Company landed at noon and immediately instituted salvage operations. Major Schmidt, who was the son of the 4th MarDiv commander, remained aboard the division command ship, functioning as a liaison officer and tank employment advisor.

Based on reports from the Underwater Demolition Teams, the 4th Tank Battalion had two options for getting ashore. The first and most desirable option was by way of the channel off Blue Beach One, through which LCMs could proceed directly to the beach. The other option was to beach the LCMs on the reef and have the tanks move ashore under their own power.

As it turned out, neither option was satisfactory—the channel was receiving intermittent heavy mortar and artillery fire. The reef option posed a problem because heavy swells made it difficult to beach the LCMs by early afternoon.

Contrary to expectations, the coral shelf off Yellow Beach 2 proved to be the best place to land; however, all tanks landed under heavy artillery and mortar fire. The prearranged method of guiding tanks to the beach with LVTs did not function because of a lack of communication and coordination. The alternate method, guides on foot, was used and proved fairly successful, except for the intense gunfire, which posed an extreme hazard.

Major Neiman had a novel approach to locating submerged potholes and craters. “We found a solution, called toilet paper…we took two tankers…and put one man in the water with goggles and swim fins and a roll of toilet paper, swimming face down in front of each tank. We put another man on the slope plate of each tank to give hand signals to the driver through his periscope. The guy swimming … if he came across a pothole, which they did periodically, they would just swim around it and uncoil the toilet paper as they went. The water over the reef was very smooth, so the toilet paper would just provide a perfect pathway around the pothole.”

One of the volunteers, Pfc. Emmett F. Kirby, was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for volunteering to “lead his tank from the coral reef through the lagoon to the beach … until mortally wounded [his third wound].”

Shortly after noon, Regimental Landing Team 25 (RLT-25) requested tank support. LCMs carrying Company A’s M4A2 Shermans responded, but heavy swells forced the coxswains to jockey their 50-foot landing craft against the reef fringe, slowing the landing. The LCMs dropped their bow ramps, signaling the 30-ton steel monsters to plunge into the reef’s shallow water off Blue Beach 2.

Almost immediately, two of the tanks “flooded out;” salt water shorted out their electrical systems. Lieutenant Gerald M. “Max” English, in a tank named “King Kong,” recalled, “We hit a shell hole, and we had water that came bubbling in. It hit the batteries, and started forming [chlorine gas]. We had to open our hatches. We had seawater coming in, but we had to have some way of getting that gas out. We couldn’t breathe.”

As Company A’s M4s made their way toward the beach, a curtain of artillery and mortar fire erupted around the slow-moving armored vehicles. Shell geysers erupted close aboard the tanks, but none suffered direct hits, unlike the troop-carrying amtracs. Several burning hulks littered the reef.

After landing, Company A immediately moved over to support Battalion Landing Team 1/25 (BLT-1/25) on Agingan Point. The two units had trained in tank-infantry tactics after the Roi-Namur operation, including conducting a school for infantry officers to teach them the capabilities, limitations and tactical uses of tanks.

In addition, the tank battalion had installed an improvised tank-infantry telephone on the rear of each tank. Ken Estes wrote in Marines Under Armor, The Marine Corps and the Armored Fighting Vehicle, 1916-2000, “The troops trusted the tank far more than the artillery as a supporting weapon, since the latter could occasionally fire on their own positions. The tanks never posed such a friendly-fire problem”

The infantry assault on Agingan Point sputtered out when the advancing troops received enfilade fire from a maze of weapons positions, as well as from the patch of woods adjacent to the promontory, which inflicted many casualties and prevented the survivors from moving forward. The Fourth Marine Division in World War II noted, “The First Battalion, Twenty-fifth … continued to receive withering enfilade fire from Agingan Point. The enemy was making a determined effort to smash the invasion on the beaches.”

Combat Correspondent Sergeant David Dempsey was helping with the wounded. “A private first class stretcher case expressed the desire to relieve himself. A Corpsman handed him the helmet of a near-by sergeant, who was also a casualty. The sergeant lay there and watched in horrified fascination as his helmet was subjected to its ultimate indignity. ‘That I should live to see the day,’ he groaned, ‘when a PFC should do that in my helmet.’”

When the LCMs carrying Company B’s 14 Shermans shoved off from the LSDs and started for the beach, one sank just as it left the LSD; the crew was rescued and re-embarked aboard the LSD. Another M4 had its deep-water fording gear smashed in an unexpected shift of weight in the LCM and, as chance would have it, the same craft took a direct hit from a Japanese shell, killing four and wounding five, including the platoon commander.

Three tanks made it to shore, but the next three were directed to land on Blue Beach 1 because of heavy artillery fire. One of these “drowned out” when it lumbered into a large depression in the reef.

Six of Company B’s tanks were ordered to land on Green Beach 2, a 2nd Marine Division beach 1,000 yards away from its planned landing beach. The tank platoon commander protested, but he was overruled and in they went. They landed on the reef and proceeded shoreward in two columns, each led by a guide, one of whom was killed by shellfire. In the center of the lagoon, about halfway to the beach, they encountered very deep water and five tanks were completely submerged and abandoned.

Only one of the six made it to the beach, but it was immediately shanghaied by the 2nd Tank Battalion and did not return to the 4th Marine Division until several days later. So, for all intents and purposes, only four Company B tanks of the original 14 were available to support the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marine Regiment.

Company C’s 14 tanks were floating just off Yellow Beach 2, waiting for the call to land. When the call came, Major Neiman had difficulty securing permission. It took him almost two hours and he explained, “I went aboard the control boat and ‘talked’ the Control Officer into letting us go. While we were circling in our landing craft off the beach, a landing craft came off the beach … with a half dozen UDT men. I hailed them and he pulled the boat over to my craft, and I jumped into his boat.

“I asked him if he knew a good spot where we could be sure there were no underwater obstacles or mines. Just at that point there’s a big explosion, near the beach, inland. He says, ‘See all that smoke? Head for that and you won’t have any trouble at all.’ So that’s what we did.”

Shortly after noon, the LCMs grounded on the reef 800 yards from the beach and unloaded Company A’s tanks in about five-and-a-half feet of water, proceeding toward the beach in a column of platoons.

“There was a long pier that the Japanese had built from the sugar mill at Charan Kanoa,” Neiman explained, “where we were supposed to land, out to the edge of the reef…. Somebody at division headquarters decided that it would be an ideal place for the tanks to land, and they could run right up that concrete ramp.” The veteran officer was skeptical.

“We figured the Japanese would certainly have the whole channel, especially that ramp, zeroed in with their heavy weapons. Sure enough, the first vehicles that tried it were amphibious tanks, and they got blasted.”

Lieutenant English recalled, “They [Japanese] waited until we got on the beach. They were throwing harassing fire out there [on the reef], but nothing heavy until we got on the beach. A lot of amphibious tanks got pinned down real close to the waterline, but we went inland.”

Neiman took his company to an assembly area, where he received orders to proceed to the O-1 phase line 1,200 yards inland. He spread the company out in a frontal assault with his right flank on a road running from Blue Beach 1 to Aslito airfield. After traveling some distance, the tanks not on the road became bogged down and were abandoned under fire.

Neiman had the remainder of the company travel on the road until they had outrun the supporting infantry. At that point, he withdrew rather than give the Japanese soldiers an opportunity to “plant” magnetic mines on his tanks. Three of Neiman’s tanks were damaged when an enemy soldier was able to attach magnetic mines over the engine compartments.

There probably would have been more tank casualties except for Neiman’s foresight. “Before we went to Saipan we studded the side of the tanks with little pieces of reinforcing steel bar. Then we bolted [wooden] 2-by-12s to the sides and put a 1-by-3 and nailed it to the bottom. We had perfect concrete form, and we poured concrete in.

“Now we had two inches of lumber [and] two inches of reinforced concrete that a projectile would have to hit and go through before it even reached the armor plate. We did it for all our tanks. We figured the little added weight was not going to bother us as much as the extra protection was gonna help us.”

By 6 pm, 10 flame-throwing light tanks of Company D had landed. They were placed in an assembly area 150 yards inland of Blue Beach 2 and ordered to stand by for the night. Three tanks from the 3rd Platoon were held aboard the LSD because there were insufficient LCMs to land them. The entire 1st Platoon spent the night in the LCMs, as the channel they were going to use was under heavy shellfire.

The “Satan” flame tanks were generally attached to Company A and were held in reserve until called to conduct a mission—mostly against Japanese defenders in caves. During the mission, they would be provided cover by medium tanks and, when it was completed, they would return to their assembly area.

By nightfall, the beachhead was only 1,300 yards inland at its maximum penetration. Heavy artillery fire, particularly from Agingan Point, pounded the beachhead. The 5th Battalion, 14th Marines sustained the heaviest losses. The battalion commander, Lt. Col. Douglas E. Reeve reported: “All of Baker Battery’s guns had been knocked out, two guns in Able Battery knocked out, one gun in Charlie Battery…. When I say ‘knocked out,’ I mean just that—trails blown off, sights blown off, recoil mechanism damaged, etc.”

D-day had been expensive, both in personnel and equipment; however, most of the 4th Tank Battalion’s armor was recovered, repaired and placed back in service, except for three tanks that remained in the water and now serve as a memorial to the battle.

On June 16, the Japanese garrison received an encouraging message from the Emperor. After reading it, Lt. Gen. Saito was grateful for “the boundless magnanimity of the Imperial favor, which we hope to requite [revenge] by becoming the bulwark of the Pacific with 10,000 deaths.”

Saito immediately orchestrated an attack against the lines of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, 2nd Marine Division, and, to a lesser extent, 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines. The Japanese force consisted of four companies (36-44 tanks, the largest Japanese tank attack of the Pacific War) of the 9th Tank Regiment, a thousand men of the 136th Infantry Regiment, and the 1st Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force.

At 3:30 am on the 17th, Captain Claude G. Rollen, Company B, 6th Marines, reported hearing enemy tanks and soldiers approaching his position. He immediately requested illumination and naval gunfire. “All prepared concentrations were called down in front of the forward companies, including 75mm pack howitzer, 81mm mortar, and the companies’ own weapons,” according to Major James A. Donovan, Jr., executive officer of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines.

“At 0345, the first wave of tanks began to enter Company B’s sector,” General Holland Smith said, describing a Japanese officer who, “standing in the turret of the lead vehicle, waved his sword in the manner of a cavalryman charging, while a bugler sounded the call.”

Donovan went on to say, “Their squeak and rattle could be distinguished above the shellfire and long bursts of machine-gun fire…. The battle evolved itself into a madhouse of noise, tracers and flashing lights. As the tanks were hit and set afire, they silhouetted other tanks coming out of the flickering shadows to the front or already on top of the squads.”

“Many of the tanks were ‘unbuttoned,’ [turrets open] the crew chief directing from the top of his open turret,” Donovan said. “Some were being led by a crew member on foot. They seemed to come in two waves, carrying foot troops on the long engine compartment or clustered around the turret, holding on to the hand rail.”

One Marine recalled that the enemy crewmen would “halt, jump out of their tank, sing songs and wave swords. Finally, one of them would blow a bugle and jump back in the tank if they hadn’t been hit already. Then we would let them have it with a bazooka.”

Swarms of Japanese infantry followed a second wave of tanks. Marine heavy machine guns, bazooka teams, a two-gun 37mm section, riflemen, and tanks from the 2nd Tank Battalion blazed away at the enemy tanks. The Marine tankers quickly realized that their armor-piercing shells were passing clean through the lightly armored Japanese armored vehicles without exploding, so they switched to high-explosive 75mm rounds, which demolished them.

Donovan related that, “The Japanese tanks … appeared confused. As their guides and crew chiefs were hit by Marine rifle and machine gun fire, what little control they had was lost. They ambled on in the general direction of the beach, getting hit again and again until each one burst into flame or turned aimless circles only to stop when hit.”

According to his Navy Cross citation, one Marine “accounted for four hits on four different tanks with his rocket launcher, and then, after running out of rockets, climbed upon a fifth tank and, with utter disregard for his own personal safety, dropped an incendiary grenade in the turret, disabling the tank.”

The main Japanese tank-infantry attack was wiped out by 4:20 am. However, snipers and scattered remnants continued to fight for several more hours. At daybreak, the crippled and surviving tanks were finished off by the 75mm half-tracks of the Regimental Special Weapons Company.

The counterattack was an unmitigated disaster; the enemy lost between 24 and 31 tanks and hundreds of irreplaceable soldiers, including the commander of the tank regiment. Brig. Gen. T.E. Watson proclaimed, “I don’t think we have to fear Jap tanks any more on Saipan. We’ve got their number.”

Major Donovan recalled, “Just before dawn, the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division landed. Comprised of several National Guard units from New York, they had been called to action in 1940 and were now the first National Guard division to play a part in the Pacific War.

“Despite the fighting of the previous day, their path was far from easy. The beaches may have been cleared of immediate danger, but the landscape was that of total war…. Disabled LVTs and boxes of C-rations were scattered across the beach. Bodies of dead Marines that had not been recovered bobbed in the surf.… The leaves on battered trees and underbrush were covered with a fine, gray dust.”

Combat correspondent Gilbert Bailey wrote: “The Japanese fell back gradually, by night, to the natural caves and prepared bunkers in the interior of the island, burying their dead as they went and dragging their equipment with them.”

On June 24, the “crap hit the fan!” Holland Smith received a message from Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, Commander, Fifth Fleet, and Smith’s boss: “You are authorized and directed to relieve Maj. Gen. Ralph Smith from command of the 27th Division, U.S. Army, and place Maj. Gen. [Sanderford] Jarman in command of this division….” Spruance sent the message as a result of Smith’s loss of confidence in Ralph Smith’s “lack of aggressive spirit.”

Holland Smith in Coral and Brass wrote, “I told [Spruance] on board the Indianapolis that the situation demanded a change in command. He asked me what should be done. ‘Ralph Smith has shown that he lacks aggressive spirit and his division is slowing down our advance. He should be relieved.’ Relieving Ralph Smith was one of the most disagreeable tasks I have ever been forced to perform.… However, there are times in battle when the responsibility of the commander to his country and to his troops requires hard measures. Smith’s division was not fighting as it should, and its failure to perform was endangering American lives.”

Ralph Smith’s relief quickly became an inter-service controversy that produced a great deal of animosity between the Army and Marines. Smith urged Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Commanding General of U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas, that “no Army combat troops should ever again be permitted to serve under the command of Marine Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith.”

Richardson was so upset that he appointed a board of inquiry to examine the facts involved in the relief. Not surprisingly, the Army board determined that the relief of General Ralph Smith “was not justified by the facts.”

Maj. Gen. George W. Griner, who took command of the 27th after the relief, considered that Holland Smith “is so prejudiced against the Army that no Army Division serving under his command alongside of Marine Divisions can expect that their deeds will receive fair and honest evaluation.”

The change of command did not materially affect the progress of the battle. The Americans continued to slowly push the Japanese back over the next two weeks, and the Japanese continued to resist. But with supplies running low and there being no possibility of receiving reinforcements, the defenders’ only desire was to kill as many of the enemy as possible before they themselves died.

On July 4, General Saito, knowing the battle was lost, ordered a final gyokusai attack (breaking of the jewels), known by the Marines as a Banzai attack. Major Hoshida Hiyoshi, captured Intelligence Officer, 43rd Division, explained, “They knew at the outset that they had no hope of succeeding. They simply felt that it was better to die that way and take some of the enemy with them than to be holed up in caves and be killed.”

Saito told his officers, “I will advance with those who remain to deliver still another blow to the American Devils, and leave my bones on Saipan as a bulwark of the Pacific.” Saito held a final conference with his remaining commanders and decided to launch an attack on the evening of 6-7 July against the Army’s 27th Division, where a 300-yard gap existed between the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 106th Infantry.

Messengers were sent out to alert the scattered units about the coming attack. Many provisional units were formed in an effort to achieve some degree of tactical unity among the assorted units and individuals. Some of the soldiers and civilians, estimated to be up to 3,000, were without weapons and equipment and were armed only with hand grenades and crudely-fashioned bamboo spears.

Of the many civilians still remaining in Japanese territory, Saito remarked, “There is no longer any distinction between civilians and troops. It would be better for them to join in the attack with bamboo spears.”

On the afternoon of July 6, General Smith visited the 27th Division’s command post “and warned [Griner, the newly appointed division commander] … that a banzai attack probably would come down … late that night or early the next morning. I cautioned him to make sure that his battalions were physically tied in.… I left his command post satisfied that I had done all that was possible for a general to do.”

Saito gave the order to march. “I advance to seek out the enemy. Follow me.” However, in the early morning hours of the 7th, according to a staff officer, “The tired general, feeling that he was too aged and infirm [he had been wounded earlier by shrapnel] to be of use in the counterattack, held a farewell feast of saki and canned crab meat and then committed suicide.”

One account states that Saito had his adjutant shoot him in the head after the general made a ritual cut in his stomach. His body was then burned to keep it from falling into American hands.

Sometime around 4 am, the main body of the attackers started south between the shoreline and the cliffs bordering the Tanapag plain. Patrols from the 27th Division detected the advance of the large mob of Japanese soldiers and called in unobserved artillery and naval gunfire on the ruckus. First Sergeant Mario Occinario, 1st Battalion, 105th Infantry, recounted how “We began to hear this buzz. It was the damnedest noise I ever heard, and it kept getting louder and louder.”

Upward of 3,000 Japanese soldiers, including wounded and crippled troops, participated in the attack down the railroad track. The blow fell at 4:45 on the gap between the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 105th Infantry. The Americans were hit from the flank and, after the enemy had moved through the gap, the rear. Almost as soon as the attack was launched, communications were lost to the rear, isolating the two battalions and leaving the soldiers fighting for their lives.

Major Edward McCarthy, commanding 2nd Battalion, described the onslaught: “It reminded me of those old cattle stampede scenes in the movies. The camera is in a hole in the ground and you see the herd coming and then they leap up and over you and are gone. Only the Japs just kept coming and coming. I didn’t think they’d ever stop.”

Lieutenant (j.g.) C.J. Blanc, Naval Gunnery Liaison Officer with the 1st Battalion, 105th Infantry, gave an eyewitness account: “At 0450, he heard firing on the perimeter. A Japanese force, so great that it was impossible to give any estimate of the number, was seen rushing down on both sides of the railroad. The enemy was armed with clubs and knives, as well as service weapons. They were running and shouting in a frenzied manner, packed so closely that it was hardly necessary for our troops to take aim.

“The enemy on the cliff side of the corridor continued to stream on to the southwest, as others engaged the two battalions in great numbers. At 1030, the two battalions had been decimated by heavy mortar fire, and fighting had become practically an individual, every-man-for-himself, hand-to-hand affair.” Lieutenant Blanc and seven men worked their way southwest, following a route between the railroad and the coast, until they were able to enter friendly lines.

Shortly before 5 am, the full force of the attack struck the 27th Division’s front lines. In less than half an hour of fierce close-quarters fighting, the American 1st Battalion’s positions were overrun, but the 3rd Battalion on high ground was able to hold. The Japanese momentum carried them toward the 3rd Battalion, 10th Marines (artillery battalion) in position 600 yards behind the Army lines.

“Small-arms and machine-gun fire was heard to the front and right front about 0300 and it appeared to get closer,” 1st Lt. Arnold C. Hofstetter, Battery H, 3/10, recounted. “The gunners were told to cut time fuses to 4/10 second, to get a close ricochet. Japs broke through a wooded ravine shooting cannoneers from their posts, forcing the remainder of the firing battery to fall back about 150 yards and set up a perimeter. We held out there until about 1500 [hours], when Army troops relieved us.”

The Japanese continued to advance along the railroad track, forcing Battery I to fall back after all its small-arms ammunition had been expended. By 5:30 am, they had advanced 500–600 yards to the 105th Infantry command post. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 105th Infantry were cut off.

The 27th Infantry Division Report of Operations noted, “Some troops … having exhausted their ammunition, swam out to the reef and were picked up by the small boats of a destroyer.” In a desperate action that lasted several hours, the U. S. soldiers were finally able to force the Japanese survivors to withdraw.

In other sectors, a mixed force of soldiers and Marines rallied to slaughter the attackers; the battered survivors in small, disorganized bands retreated back to their starting point. The true scope of the enemy attack was revealed at daylight: Japanese bodies littered the battle area. It was estimated that over 4,000 Japanese lost their lives in the great banzai attack. Over 400 Americans were also lost. Mop-up operations lasted for another two days, but the fight was gone from the Japanese.

By July 9, mopping-up operations were completed and organized Japanese resistance had ceased. At 4:15 pm on July 19, General Smith declared the island secure. But there was no joy in victory, no sense of satisfaction.

Of the 71,000 troops that made up Holland Smith’s Northern Troops and Landing Force, it is estimated that 3,674 Army and 10, 437 Marine Corps personnel were killed, wounded, or missing in action. This total of 14,111 represents about 20 percent of the combat troops committed.

Out of the entire Japanese garrison of 30,000 troops, only 921 prisoners were captured; the rest died. The Japanese commanders—Saito and Vice Adm. Nagumo—and some 5,000 others committed suicide rather than surrender.

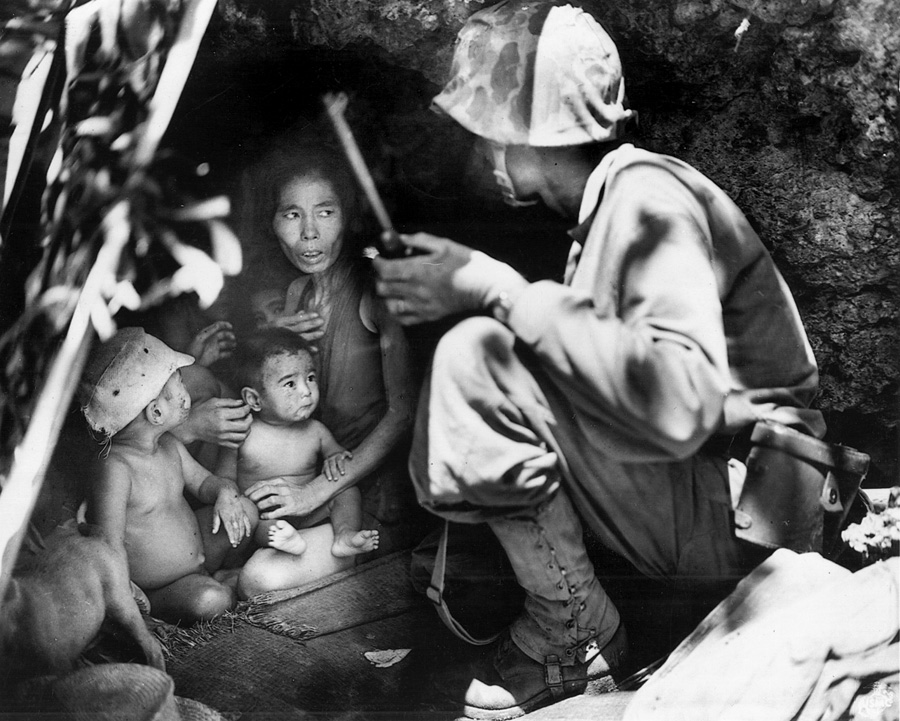

Sadly, the massive slaughter between combatants did not end the horrors. The island was inhabited by 25,000 to 30,000 Japanese civilians, who were told by Tokyo that the American occupation would mean torture, rape, and brutality. To escape what they thought was a certain fate, groups of islanders huddled around exploding hand grenades, while others dropped their children off steep cliffs before jumping themselves. Thousands of civilians committed suicide before American interpreters were able to convince them that they would be treated fairly.

The suicides in Saipan drew considerable attention and praise in Japan. A Japanese correspondent praised the women who committed suicide with their children by jumping from the cliffs, writing that they were “the pride of Japanese women.”

(Author’s note: On a tourist visit to Saipan, I stood atop the 300-foot “suicide” cliff, where hundreds of civilian men, women, and children jumped or were thrown to their deaths. It was hard for me to imagine what drove them to commit suicide. It is one thing to read about the tragedy, but to look down at the jagged rocks below—it’s just too hard to understand.)