By John W. Osborn, Jr.

When British Prime Minister Winston Churchill created the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to organize guerrilla resistance against the Nazis, he famously ordered it to set Europe on fire. But those officers heading into the wildest, most remote, part of Europe would be the ones almost burned—by their erstwhile allies instead of their common enemy.=

Occupying 11,000 square miles of the Balkan peninsula facing the west cost of the Adriatic Sea with Yugoslavia to the north and northeast, Macedonia and Greece to the east and southeast, Albania was what the Old West might have resembled had Billy the Kid and the Apaches won out over the sheriff and the cavalry. Its one million people were torn by deep religious divides—Orthodox, Catholic, Muslim—and even worse, by sometimes violent tribal differences, the Ghegs in the north, Tosks in the south.

Guerilla War in Albania

After 500 years of Ottoman rule, Albania finally achieved independence in 1912, but the German prince installed by the great powers as king to stabilize the country fled in a year. In 1924, a northern tribal leader seized power and proclaimed himself King Zog I, his rule in equal parts comic opera, corrupt, and cruel. He survived 56 attempts on his life, once shooting it out with assassins in the Vienna Opera House, but made his fatal mistake in reneging on debts he owed Italy. Benito Mussolini landed five Fascists divisions in Albania on April 7, 1939.

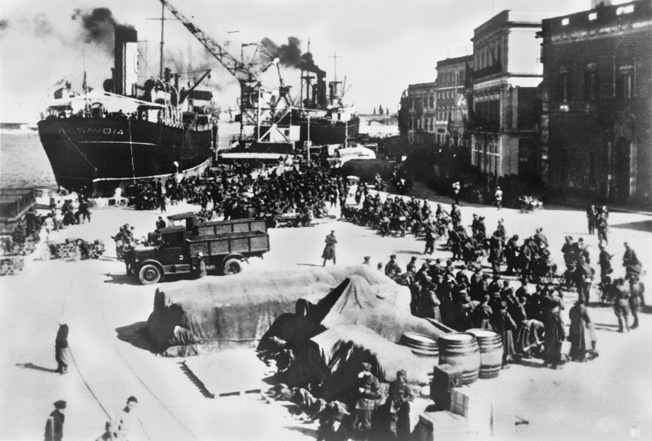

A confused Albanian policeman asked the Italian troops for their passports. “We have none. We’ve come to occupy your country,” an Italian officer answered. In five days, for five Italians and 15 Albanians killed, the Fascists did just that. Zog exited for Greece in a caravan of limousines with as much in gold and luxury items as he could carry. But the Albanians now had someone else to despise even more than Zog, and sporadic guerrilla resistance began.

After Mussolini entered World War II on the side of Hitler, the British sent a colonel into Albania in April 1941 to help the resistance, but he was soon captured. It would not be until April 16, 1943, that two more SOE officers, Lt. Col. Neil McLean and Captain David Smiley, parachuted into northern Greece and crossed the border.

Others would follow, including a former lieutenant in the Spanish Foreign Legion, Peter Kemp; Himalayan explorer Bill Tillman; and Reginald Hibbert, whose view of events in Albania in the years to come would put him bitterly at odds with his fellow SOE officers. “Now that we were on Albanian soil, we had achieved the first part of our mission,” David Smiley wrote in a memoir, Albanian Assignment, decades later. “The next stage—getting in touch with Albanian guerrillas and encouraging them to fight the common enemy—was not to prove so easy.”

SOE operations were hampered by woeful British ignorance about Albania. London had only a lower-level diplomatic presence there before the Italian occupation, and the main source of information had been an elderly Englishwoman who had lived there for 20 years.

Worse, the language was one of Europe’s most ancient, obscure, and difficult. “We were mostly dependant on interpreters,” Peter Kemp was to write, “whom we could trust neither to render our own words faithfully nor to give us a true picture of local reactions.” While on a mission to the capital, Tirana, Kemp’s SOE companion pulled out a handkerchief to blow his nose and their Albanian guide quickly yanked it from him. “No Albanian peasant would use a handkerchief,” Kemp realized.

Clashing Political Beliefs in the Allied Camp

The mission’s conduct and ability to navigate the labyrinth of Albanian politics were not helped by the strongly conservative bent of most of its members. After the war, Neil McLean became a Tory Member of Parliament on the party’s fringe, while Peter Kemp was one of the few Englishmen to fight with Franco’s side during the civil war in Spain. In September 1942, the Albanian Resistance had merged into a shaky Levizje Nacional Clirimtare (LNC, Council of National Liberation), but the dominant group in it had more in mind than just driving out the Italians.

The country’s Communist Party had been founded in Tirana in secret, in November 1941. Its general secretary, Enver Hoxha, had been educated in Paris and, ironically for a Marxist, owned a tobacco shop. The military commander, Mehmet Shehu, had also fought in Spain—with the Loyalists, against Kemp’s side.

Of these characters, Smiley wrote, “Hoxha had quite a sense of humor, and over a glass of raki could be cheerful and amusing, in contrast to his dour and morose companion, Mehmet Shehu…. He may have disliked us, but at least he concealed his feelings, whereas with Shehu, you could feel the hostility.”

“This dilemma was our constant companion in our efforts to promote resistance: if we were to do our job properly, we were bound to put innocent people in jeopardy; they had to stay and face reprisals while we found safety in flight,” wrote Kemp. “In the service of our country, we simply had to harden our hearts.” So the British radioed for arms drops, joined in attacks on the Italians, and helped the communists organize a partisan brigade.

“The Best of a Very Bad Lot”

Italy’s sudden capitulation in July 1943, though, made the situation for Albania only worse. Needing Albania as a major source of chromium, the Germans rushed in two divisions. Then, the LNC’s fragile cohesion finally came apart, Republicans forming the Balli Kombetar (BK, National Front), while Major Abas Kupi, the leader McLean and Smiley most favored, led Legalite, incredibly seeking the restoration of the despised King Zog.

The SOE leadership ended up seeing Hoxha as “the best of a very bad lot” and dropped most of its arms to him. Never mentioning Reginald Hibbert’s name in his account, Smiley bitterly complained that the “BLOs [British Liaison Officers] attached to the partisans repeatedly told by them that Kupi was collaborating with the Germans, had absorbed these lies and signaled them.”

The political infighting soon affected the fighting with the Germans. Smiley and BK personnel were preparing an ambush when communist partisans turned up and tried to muscle their way in charge.

“The object, without doubt, was to prevent the Balli Kombetar from carrying out an ambush that would give them credit in the eyes of the British,” Smiley seethed. He angrily ordered them off “and a short while later my temper was cooled by the fine sight of a big German half-tracked troop carrier…. As the carrier drew closer, every one of us held his breath; then it went up on the mines with a flash of orange flame followed by a cloud of smoke, and the sound of the explosion echoed through the hills. I had taken a photograph as the mines exploded; by the force of the explosion, I estimated that all eight mines must have detonated at once. Once the smoke had cleared, everyone opened fire on the troop carrier; I exchanged my camera for the 20mm Breda, and was delighted to see several of my shots score direct hits. A few Germans jumped out of the carrier and tried to run back down the road but all were shot, and the others tried to take cover behind the carrier. In time, the shooting stopped and a silence followed only broken by the groans of some of the wounded.”

Eighteen German soldiers died.

But when McLean, Smiley, and Kemp were preparing with the communists to ambush a large oncoming German column, Mehmet Shehu suddenly called it off. “Our battalion has been surprised by a German post on that hill,” Kemp recalled Shehu’s claim. “We must withdraw.”

“Do you mean to tell me that 800 partisans cannot attack and wipe out a post of 20 Germans?” McLean raged. Shehu could not be budged, and the British had to settle for shooting up a solitary passing staff car.

“At that time, we attributed this fiasco to rank cowardice,” Smiley wrote. “In fairness to Shehu, however, he was a brave man, and to the partisans themselves, we did not then know that Shehu had received a directive ordering him not to fight the Germans and Italians, but to preserve his brigade in readiness for fights with their political opponents that lay ahead.”

“I am a Soldier and Not a Politician”

In November 1943, McLean and Smiley were brought out of Albania by patrol boat for debriefing in Cairo while a new mission led by Brig. Gen. Edmund Davies parachuted in to take over. Davies got a rude introduction to guerrilla resistance, Albanian communist style, in his first encounter with Hoxha. “The military situation depends entirely on the political situation, so why will you not first give us your impression of world politics?” These were Hoxha’s first words to Davies.

“Because I am a soldier and not a politician,” was Davies’s frustrated response. His aggravations continued to mount as his constant wrangling with the resistance groups to reunify and discipline them left him little opportunity to attack the Germans.

“I felt that we could bring the country to a standstill with two brigades of British troops acting as guerrillas, or with half a dozen Commando units,” Davies later complained. Instead, he was the one on the defensive as thousands of BK partisans defected to the Waffen SS to fight the communists, Abas Kupi unsuccessfully sought a truce with the Germans for their aid in his own struggle with Hoxha, and ruthless German counterinsurgency operations drove Davies and the resistance into the mountains for a harsh winter. Then on the morning of January 8, 1944, Davies and his mission were ambushed by renegade BK fighters.

Davies was wounded and was captured along with two other officers, ending up a prisoner in the high security Colditz facility. The mission chief of staff, Colonel Arthur Nicholls, and Captain Alan Hare fled into the snows, but Nicholls died of exposure and gangrene, the only SOE fatality in Albania, while Hare lost several toes before fleeing south.

Peter Kemp’s Escape from Albania

Peter Kemp was also on the run. He had been sent into the Albanian province of Kosovo to organize Muslim separatists but had been betrayed. He never ascertained the identity of his betrayer and had to flee toward Macedonia.

“It was still snowing when we continued our journey in the darkness,” he later wrote, ”but the moonlight, filtering through the clouds, was reflected from the snow to diffuse a weird, pale light over the landscape. Soon we descended from the hills into a broad valley and followed the course of a river northwards over open meadows bounded by hedges.

“Crossing the flat, snow-covered ground in single file we must, I felt, be easily visible to any hostile patrols or sentries. The two Montenegrin partisans acted as scouts, moving about fifty yards ahead of us. Luckily they had sharp eyes.

“As we were crossing a field, they halted suddenly, then signaled us frantically towards the cover of a hedge. Crouching in the ditch beside it, I watched a file of men approaching on our left; I had counted a dozen of them when I felt a tug on my sleeve.

“‘Tedeschi!’ he hissed. ‘Over there, too!’ He pointed to a field, where I could make out another and larger party moving parallel with the first. ‘But they haven’t seen us—not yet.’

“Slowly, agonizingly slowly, the two German patrols stalked across the fields on either side of us. Silent and motionless we lay in the shallow ditch, holding our breath and sweating with anxiety….

“They plodded steadily past us, seeming to look neither to right nor left. We lay hidden for a full five minutes after the last files had disappeared into the night; then we moved forward in a series of bounds from hedge to hedge, floundering across the open fields as fast as we could pull our feet through the deep snow.”

Kemp crossed the border and was flown out. In April 1944, McLean and Smiley parachuted back into Albania with Major Julian Amery, son of a member of Churchill’s cabinet and another future hard-right member of Parliament. They worked with Kupi to launch a series of attacks on the Germans in the north, hoping to earn him more arms from the SOE, but only a trickle dropped in.

Civil War in Albania

In the meantime, Hoxha’s army in central and southern Albania grew in the first half of 1944 from 5,000 to 20,000, and the day Smiley called “the blackest in the history of our mission” finally came, when Hoxha’s forces attacked Kupi’s. “Civil war had finally reached us,” Smiley wrote. “All our high hopes of getting Kupi to fight the Germans had been shattered, for he would obviously have to move to protect his own region and its villages from the ravages of the partisans.

“We marched for two days, passing through all the signs for preparation for civil war; Zogist bands were taking up positions, and in the distance, smoke could be seen rising from the Zogist villages which the partisans were burning down,” Smiley recalled. He split off from McLean and Amery to make contact with other Legalite groups and had several close calls with the communists and the Germans, and even the British.

Smiley had to hide in a drain from partisans and was then alerted to exit a house he was sheltering in five minutes ahead of others. While riding with Legalite members in a car with his uniform on, a German sentry slowed them down but did not look inside the vehicle and waved them on.

Smiley was walking a back road with armed Legalite men, still in his uniform, when a lone German on a bicycle pedaled up behind them, got off, and walked alongside them almost a half hour before riding on! “My companions thought this a huge joke and Ramiz kept slapping his sides with laughter,” Smiley recalled. “I often wonder who the German thought I was; perhaps he knew and did the only possible thing, for we were all armed and could easily have murdered him.”

Smiley switched to an Albanian gendarmerie uniform and chanced hitching a ride with German soldiers in the back of a truck, fez and head hung low. The truck was attacked by Royal Air Force planes, and he had to join the Germans in hotfooting to cover. “We lay in the ditch as the fighters zoomed overhead, but luckily for us, the shower of bullets hit the road some way off, for the pilot had overshot his target,” Smiley remembered. “The German in the ditch beside me shook his fist at the disappearing aircraft, and, to show there was no ill-feeling, I did the same.”

Smiley soon joined up again with McLean and Amery, and they and the rest of the mission made for the coast as the communists demanded they turn themselves in for trial. “Our work in Albania was over, our mission had failed,” a depressed Smiley wrote. “It was ironic that our main thoughts were now of an attack by the partisans, our former colleagues, rather than the usual threat from the Germans.”

The Tyranical Rule of Enver Hoxha

The mission was evacuated by sea on the nights of October 13 and 14, 1944. They had dispatched a message to London requesting that Abas Kupi be brought out with them, but a pro-communist SOE officer had blocked it. By the time a second message got through and was approved, Kupi had escaped on his own.

In November 1944, the Germans also withdrew, and within weeks Enver Hoxha was in control. “With a very small British and American intervention, we could have saved Albania for the West,” Julian Amery was convinced. Closer to the events, Reginald Hibbert disagreed: “A revolutionary force was released in Albania in 1944 and that was the primary force which swept Enver Hoxha to power.”

Until his death in 1985, Hoxha ran a regime as notorious for its bizarreness as brutality. He permanently maimed the landscape with over a million concrete bunkers and pillboxes. He declared Albania the world’s only official atheist country, destroying every church and mosque, arresting every priest and imam. He broke with Russia, then China, as not communist enough. “Who disagrees with our leadership in some point will get a bullet into his head,” threatened Mehmet Shehu, the prime minister. In 1981, he got one, officially a suicide.

Operation Valuable: One Last Foray into Albania

When Neil McLean, David Smiley, Julian Amery, and British intelligence were next interested in Albania, it was to overthrow the communists. Between 1949 and 1954, in Operation Valuable, 200 trained exiles were landed or parachuted in to organize a revolt.

Except for a few escaping to Greece, the agents were killed, with over 1,000 members of their families executed as well in reprisal. Because he was involved in the early planning for Valuable, McLean, Amery, and Smiley always blamed the tragic fiasco on the notorious double agent Kim Philby.

Though Philby undoubtedly betrayed the existence of Valuable to the communists, he had gone on to Washington as liaison with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency before the first insertion and had no knowledge of the dates or locations of the following ones.

Ever the dissenter, Reginald Hibbert bluntly said, “It was a forlorn hope to suppose that the exiled followers of the nationalists who failed in 1944 would be able to raise a following against the iron rule of the Communist Party of Albania after six years of draconian social engineering.”

When communism died in Albania, it was by sudden rioting in Tirana in December 1990, inspired inadvertently by those responsible for setting Albania on the tragic road from isolation to war and revolution, the Italians, through their television programming that Hoxha’s successors unwisely allowed to be aired. n

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is a resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has previously written for WWII History on the Spanish Blue Division, the Long Range Desert Group, the March on Baghdad, and the war in East Africa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments