By Blaine Taylor

On the evening of September 26, 1940, American radio announcer and journalist William L. Shirer noted in his later famous Berlin Diary that the next day Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano would arrive there from Rome, adding that most people thought it was for the announcement that Francisco Franco’s Spain was entering the war on the side of the Axis. Indeed, Spanish Foreign Minister Ramon Serrano Suner was already in Berlin for that expected ceremony, Shirer concluded.

Spain did not join the Axis, but something else of even greater importance did take place that day. Hitler and Mussolini pulled off another surprise. At 1 pm in the Reich Chancellery, Japan, Germany, and Italy signed a military alliance directed against the United States. Shirer candidly admitted that he had been caught off guard, and Suner was not even present at the theatrical performance the fascists of Europe and Asia staged in his absence.

Japan’s Decision to Join the Axis Powers

The formal signing of what became known as the Tripartite Pact, another milestone on the road to global war, was preceded by a top secret meeting in Tokyo on the 19th. The meeting was termed a Conference in the Imperial Presence that had been called by Japanese Emperor Hirohito. It was held in Paulonia Hall of the Outer Ceremonial Palace with everything planned and rehearsed in advance.

Reportedly, Hirohito sat motionless before a golden screen at one end of the audience chamber and said nothing while the other 11 participants at two long tables delivered their set speeches back and forth across the Imperial line of vision.

The real deliberations had already occurred during September 9-10, when Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka sat down with German ambassador to Tokyo Heinrich Stahmer to hammer out all the details. The Japanese wanted a free hand in Southeast Asia, and they should have it. The Third Reich desired pressure put upon the British fleet that still maintained naval supremacy in the Straits of Dover. Matsuoka vowed to supply it by having the Japanese Navy attack the British Far Eastern bastion of Singapore.

On Friday, September 13, an unlucky day as it turned out for the emperor, Hirohito allegedly studied their joint document word by word since it undoubtedly would lead in the end to war between the United States and the Imperial Japanese Empire. He approved the text but made one editorial change, striking out the five words “openly or in concealed form” from the type of attack that might launch Japan’s participation in World War II. His Imperial Majesty believed that they were too explicit, too close to the truth of the actual event being prepared even then by his naval staff planners.

Thus were secretly sown the future seeds of the sneak attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but as a prudent ruler, the emperor was hedging his bets in case the empire lost the war and had to regroup in a new era of enemy occupation and uneasy peace.

During the meeting of September 19, Prince Fushimi asked on behalf of the Naval General Staff that, since it was likely that such a naval war would be quite long, what the prospects were for Japan’s maintenance of her imperial strength? The prime minister, Prince Konoye, answered on behalf of the cabinet that they should be able, in the event of a war with the United States, to supply military needs and thus withstand such a protracted war.

One crucial economic item that affected all deliberations in Tokyo, Berlin, and Washington was oil for the Imperial Japanese Fleet. The Navy was acutely aware that it was dependent on both Britain and the United States for this indispensable commodity.

If the Dutch East Indies could be taken, this problem would be solved, but both the British and the Americans stood in the way. Hence a preemptive war was being considered in earnest to remove them if necessary.

Then, too, there was another consideration. As Matsuoka pointed out, the object of the pact with Germany and Italy was to prevent the United States from encircling Japan. Summing up for the admirals, Prince Fushimi asserted that the Naval Section of Imperial Headquarters agreed with the government’s proposal that the Japanese could conclude a military alliance with Germany and Italy, but warned that every conceivable measure should also be taken to avoid it.

Privy Council President Hara made a prepared statement on behalf of Emperor Hirohito himself. He asserted that, even though a Japanese-American clash might be unavoidable in the end, the emperor hoped that sufficient care would be exercised to ensure that it would not come in the near future. He added that there would be no miscalculations and thus gave his approval on that basis. Through his proxies, Hirohito had spoken.

Germany Prepares For a Long War

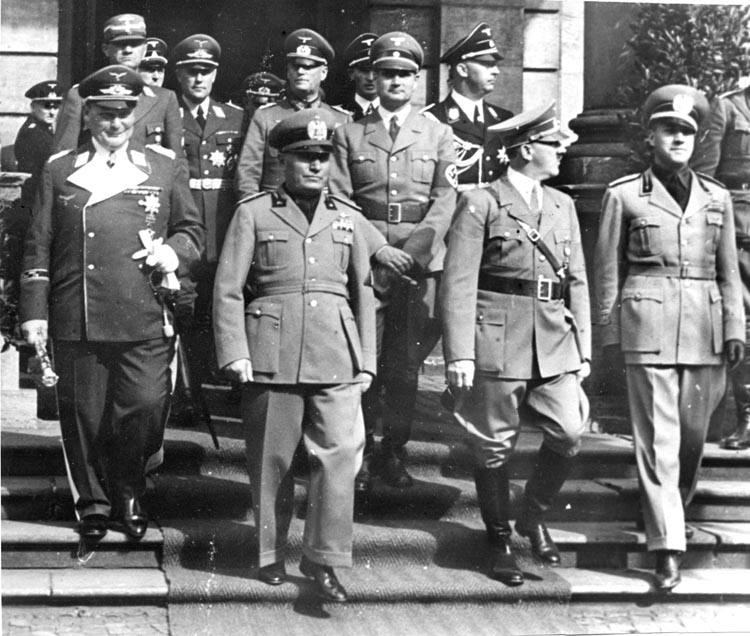

Meanwhile in Berlin, Shirer witnessed the signing ceremony, noting its showy setting, with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Ciano, and Japanese Ambassador Saburo Kurusu looking bewildered as they entered the gala hall of the Reich Chancellery. Kleig lights blazed away as the scene was recorded for posterity. Indeed, the entire staffs of the Italian and Japanese embassies were turned out in force, but no other diplomats attended. The Soviet ambassador was invited but had declined.

The three men sat down at a gilded table. Ribbentrop rose and motioned to the German Foreign Office interpreter, Dr. Paul Schmidt, to read the text of the pact, following which they all signed while the cameras ground away.

Then came the climactic moment, or so the Nazis thought. A trio of loud knocks on the giant door were heard, followed by a tense hush in the great hall. The Japanese held their breath, and as the door swung slowly open Hitler strode in. Ribbentrop bobbed up, and formally notified him that the Tripartite Pact had been duly signed.

“The Great Khan,” as Shirer mocked the Führer, nodded approvingly, but did not deign to speak. Instead, Hitler majestically took a seat at the middle of the table while the two foreign ministers and the Japanese ambassador scrambled for chairs. Then they popped up, one after another, and gave prepared speeches that Radio Berlin broadcast around the globe.

In his account, Shirer also noted that German Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, commander in chief of the Luftwaffe, in the fall of 1939 had ridiculed even the remote possibility of American aid reaching Europe before the issue of the war had been decided. The Germans thought, moreover, that the war would be over by the fall of 1940 and that American aid could not possibly arrive before the spring of 1941, if at all.

Now, all of that was changing. Shirer opined that Hitler would not have promulgated the Tripartite Pact if he thought that the war was coming to an end before winter, as there would have been no need. It was going to be a long war after all.

Flaws in the Tripartite Pact

Shirer was also on target in noticing the pact’s hidden flaws, mainly that the signatories could not lend the slightest economic or military help to one another between Europe and Asia due to great distance and the presence of the Royal Navy, Great Britain’s mistress of the world’s oceans.

By the time he had researched and published his epic tome The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich in 1960, Shirer had discovered a great deal more about what he called “the turn of the United States,” asserting that to keep America out of the war Nazi Germany had secretly resorted to actual bribery of American congressmen. Hitler would “deal” with the Americans after he had first defeated both the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union.

Indeed, in Basic Order No. 24 regarding collaboration with Japan issued on March 5, 1941, Hitler stated that the common aim of the conduct of war was to be stressed as forcing England to her knees quickly, and thereby keeping the United States out of the war altogether. The commander of the German Navy, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, backed an attack on the British naval base at Singapore by the Imperial Japanese Navy as a sure means of accomplishing this.

The Japanese then stunned everyone on April 13, 1941, by concluding a treaty of their own in Moscow on Russo-Japanese neutrality with Soviet dictator Josef Stalin. Hitler and Ribbentrop were alarmed as were their American counterparts, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. All of them believed that this new effort would release Japanese troops earmarked for a possible war with the Soviet Union for a strike south against the British and Americans instead. In the end, they were right.

In effect, the Nazis had been hoodwinked, paid back in like coin for their own August 1939 secret nonaggression pact with Stalin that the Germans had concluded without informing the pro-Axis Japanese ambassador to Berlin, General Hiroshi Oshima.

The Germans invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, and six days later urged the Japanese to do the same from the Far Eastern frontier, but to no avail. Despite persistent entreaties to do so until the very end of the war, the Japanese never broke their treaty with Stalin. Rather, it turned out to be the other way around in August 1945.

Hideki Tojo’s Rise to Power

Meanwhile, the admirals of the Imperial Japanese Navy were ready for their strike south and war with America, Britain, China, and the Netherlands, while Hitler hoped to capture Moscow and force the surrender of the Soviet Union in December 1941.

Hitler and Ribbentrop were in for yet another nasty surprise from the Far East. The Nazi chancellor had constantly urged the Japanese to avoid a direct conflict with America and concentrate instead on Britain and the Soviet Union, whose resistance was stopping him from winning his war. It never dawned on the Nazi rulers that Japan might give first priority to a direct challenge to the United States as a determinant of its wartime goals.

On the other hand, ironically, the Nazis had feared in early 1941 that Japan and the United States might in fact settle their differences amicably and that prospects for war between Japan and the United Kingdom in the Far East would then disappear. This did not come about. In July 1940, the Japanese Army invaded French Indochina, and talks between envoy Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura and Secretary Hull were broken off.

A proposed meeting between Premier Konoye and Roosevelt never materialized, and on October 16, 1941, the prince’s government fell and a new cabinet was appointed by his successor, General Hideki Tojo, nicknamed “the Razor.” Under Tojo’s government, Japan demanded a free hand in Southeast Asia, ensuring that eventual war with the United States was a certainty.

“This Means War”

On November 15, Special Envoy Kurusu, who had signed the Tripartite Pact in Berlin, arrived in Washington to aid Admiral Nomura in negotiations with the Americans. Four days later, a secret message came from Tokyo to the Japanese embassy in Washington that war was imminent. On the 23rd, Ribbentrop became aware of this also but did not believe that the United States would be attacked.

On the 28th, Ribbentrop called in Ambasador Oshima and seemed to reverse Hitler’s earlier policy of urging Japan to avoid war with the United States. If Japan reached a decision to fight Britain and the United States, Ribbentrop was confident that not only would that be in the interest of Germany and Japan jointly, but it would also bring about favorable results for Japan.

Not sure that he had heard correctly, the tense little Japanese general asked if Ribbentrop was indicating that a state of actual war was to be established between Germany and the United States. Now Ribbentrop hesitated. Perhaps he had gone too far. He answered that Roosevelt was a fanatic, so it was impossible to tell what he would do.

In Washington, the talks between Nomura, Kurusu, and Hull broke down because the Japanese diplomats refused to repudiate the terms of the September 27, 1940, Tripartite Pact. On December 3, the Japanese in Rome asked Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini also to declare war on America, and Ciano recorded in his diary on the 4th that Mussolini was enthusiastic about the idea. This was a decision that would doom him in 1943, since it brought the U.S. Army to Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy.

Over the course of December 4-5, Hitler appeared to approve a Japanese attack on the United States that the Germans would then back, but Japan feared that a quid pro quo would be demanded by the Third Reich in the form of a Japanese attack against the Soviet Union through Siberia to help relieve the pressure on the German Army then just outside Moscow.

At 9:30 pm on Saturday, December 6, President Roosevelt was at the White House with top aide Harry Hopkins reading the first 13 parts of a long decoded message from Tokyo to its embassy in Washington when he said flatly, “This means war.”

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The next morning, December 7, 1941, aircraft and midget submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked U.S. military installations in the Hawaiian Islands, allegedly catching both the Nazis and Roosevelt off guard. As Ribbentrop later testified on the witness stand at Nuremberg, the attack came as a complete surprise to the German leadership that had considered the possibility of Japan’s attacking Singapore or perhaps even Hong Kong, but never considered an attack on the United States as being to their advantage.

From his unique vantage point as the man who served as interpreter to most of the top Nazis, Dr. Paul Schmidt well remembered the scene at the Wolf’s Lair when the Pearl Harbor political bombshell burst. He recalled in his 1951 memoirs that during the night of December 7-8, 1941, the Reich Foreign Ministry’s broadcast monitoring service was first to receive the startling tidings of the Japanese sneak attack on America in the Pacific, but it was only when a second report confirmed it that Ribbentrop was duly alerted.

At first, the Reich Foreign Minister refused to believe it, asserting that they were nothing more than unverified reports and a propaganda trick of the British to which his gullible press section had fallen prey. He did, however, order that further inquiries be conducted and furnished to him later on December 8.

Dr. Schmidt recalled that both Hitler and Ribbentrop had been taken by surprise by their Asian allies in the very same way as they had often informed their Italian ally, Mussolini, of new German invasions of various countries. Now the shoe was on the other foot.

Dr. Schmidt commented wryly among his own associates within the Foreign Ministry that it seemed to be the fashion among dictators and emperors to behave that way.

The Axis Powers Go to War With the U.S.

Hitler returned to Berlin from East Prussia on December 8 and at length decided to honor his pact with Japan, which he did not have to do since he had not been informed of the Japanese intent to attack Pearl Harbor and the U.S. had not overtly attacked the Reich despite the secret naval war then going on in the North Atlantic.

Dr. Schmidt added after the war that he personally knew of no such understanding with the Japanese that would have compelled the Nazi Führer to declare war on the United States. He declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, in the Reichstag. In a single stroke, he had neatly solved one of Roosevelt’s own pressing political problems. Germany had not attacked the United States, so on December 8 in a joint session of Congress Roosevelt had only asked for a declaration of war against Japan, not the Third Reich as well.

Ironically, Hitler had feared that the hated Roosevelt would declare war on him first and had thus made his own decision on the 9th to forestall that possibility. This was duly confirmed in 1951 by Dr. Schmidt, who had gotten the distinct impression that Hitler, with a well-known desire for prestige at the expense of others, had been expecting an American declaration of war and was itching to get his oar in the water first.

The Japanese, naturally, were ecstatic, and so was Admiral Raeder. Hitler asked him if there was any possibility that the United States and Britain would abandon East Asia for a time in order to crush Germany and Italy first. The admiral did not think so, unaware that even then President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill were meeting at the White House to decide just that wartime policy: defeat Germany and Italy first, then Japan.

In Japan, Eri Hotta reported in 2013 that December 8, 1941, dawned as a cold day when its people awoke to astonishing news after 7 am on the radio that their nation was at war with both the United States and Great Britain, the very nations that had been her allies during the World War I, the latter her Navy’s model.

The die had been cast.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments