By Thomas G. Bradbeer

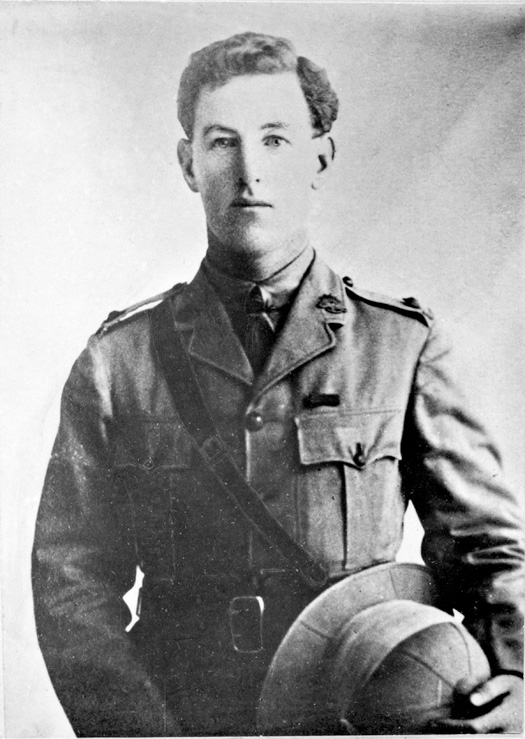

He had the distinction of being the first Commonwealth soldier to receive the Victoria Cross for valor in World War I, and many observers felt that Australian-born Albert Jacka should have earned at least three of Great Britain’s highest award. His courage and aggressive leadership style inspired unhesitating loyalty in his men and fear in his enemies, but his outspokenness and lack of respect for military niceties may have prevented Jacka from achieving even greater fame. As it was, his influence and reputation among his own men was so widespread that his battalion proudly called itself “Jacka’s Mob.”

Jacka was born on a farm near Winchelsea, Victoria, Australia, on January 10, 1893. His father, Nathaniel, was a dairy farmer who also ran a contracting and carting enterprise providing materials to Victoria’s railways and mines. As a youth—he was one of seven children—Jacka was a superior athlete, excelling at boxing, cycling, and football. After completing the sixth grade, Jacka went to work for his father. He later joined the Victorian State Forests Department, where he was working quietly when the cataclysmic events of July and August 1914 initiated the First World War.

Enlisting in the newly formed Australian Imperial Force on September 8, 1914, Jacka was assigned to the 14th Battalion, 4th Brigade, 1st Division, and embarked on the last of October for England to complete training before being committed to the Western Front. However, when Turkey entered the war as a German ally, the 1st Division was diverted to Egypt to assist in the defense of the Suez Canal.

First Taste of Combat for the NZ&A

Jacka’s battalion disembarked at Alexandria on January 31, 1915, and spent the next 10 weeks getting organized and training in the region south of Cairo. During this period of training, the Australians began to earn a reputation for being rowdy, undisciplined, and resistant to authority. Eventually, the 4th Brigade united with two New Zealand brigades and the 1st Light Horse Brigade to form the New Zealand and Australian Division under Maj. Gen. Alexander Godley. That April, the NZ&A would get its first taste of combat in what would become one of the most controversial campaigns in military history.

For the Commonwealth soldiers, the ill-starred Gallipoli campaign officially began on April 25, when the division landed at Anzac Cove in the Dardanelles. A furious battle immediately commenced, with the Australians finding themselves pinned down on a narrow beach that quickly rose into steep and rugged terrain dominated by Turkish defenders. The NZ&A held down a sector of trenches known as Courtney’s Post. Late night on May 19, a group of Turkish soldiers captured a portion of Courtney’s Post. The Australians attempted a counterattack but failed. Jacka’s platoon commander organized a diversion to keep the Turks occupied while Jacka and three other men moved to outflank them.

Jacka’s first attempt to move around the Turks failed; one man was seriously wounded and the others were pinned down by intense enemy fire. Jacka decided that one man might be able to reach the Turkish position. At great personal risk, Jacka singlehandedly charged over open ground and jumped into the trench behind the Turkish soldiers. In a matter of seconds he shot five and bayoneted two others. The remainder scrambled out of the trench and fled in panic back to their own lines. Jacka held the trench alone for the remainder of the night. When his platoon commander found him at dawn, the young Aussie reported calmly, “Well, I managed to get the beggars, sir.” For his remarkable feat, Jacka was awarded the Victoria Cross.

As casualties mounted among the Australian forces, Jacka not only survived the harsh conditions, but he seemed to thrive on the desolate battlefield. He was promoted to corporal on August 28, 1915, and raised to sergeant four weeks later. In November, he became sergeant major of Company C. A new soldier in the 14th Battalion, E.J. Rule, described Jacka at the time: “He had a medium-sized body, a natty figure, and a determined face with a crooked nose,” Rule reported. “His feat of polishing off six [sic] Turks single-handed certainly took some beating. He was not one of those whose character, manner, or outlook was changed by the high decoration which he had received. His confident, frank, outspoken personality never changed … the whole AIF came to look upon him as a rock of strength that never failed. We of the 14th Battalion never ceased to be thrilled when we heard ourselves referred to … as ‘some of Jacka’s mob.’”

Nearly 600 Men Died in the First Few Days

Jacka and the rest of the battalion saw much more combat at Gallipoli. In August, they were involved in heavy fighting at Chunuk Bair, Hill 971 and Hill 60, attempting to break out of the beachhead they had established in April and support the British landing at Suvla Bay. After one particularly grueling and fruitless attack, Jacka recorded in his diary: “Practically the whole battalion wiped out.” Indeed, nearly 600 of the 800 men assigned to the battalion had become casualties in only a few days of fighting.

In December 1915, after nine months of arduous struggle and 26,111 Australian casualties, the Allied forces began evacuating the peninsula. Jacka and the 14th Battalion went to Lemnos, where they spent the holidays. In early January the battalion returned to Egypt, where the brigade was split in half and divided between newly formed brigades. The reorganization was completed in early March, and Jacka was promoted to second lieutenant.

On June 1, 1916, the Australian contingent was sent to France to fight Germans instead of Turks. After being issued gas masks and steel helmets, the men entered the Allied trenches near Armentieres, where they quickly got their baptism of fire on the Western Front, taking part in a series of costly raids designed to draw away German units from the British attacks taking place farther south on the Somme. The next month the battalion was unexpectedly transferred south to join the disastrous Somme offensive, which had been bogged down immediately with staggering casualties—57,470 British and Canadian losses on the first day alone.

Jacka, recently assigned to platoon commander, joined the battalion around the enemy-held village of Pozieres on August 4, exactly two years after the start of the war. Prior to the start of the campaign, the Germans had fortified the village with deep dugouts, concrete pillboxes, and numerous machine gun positions overlooking likely avenues of advance. Located astride the Pozieres Ridge and studded with German artillery, the village had endured repeated Allied shelling, becoming a village in name only. A few scattered mounds of bricks and the wreckage of a windmill were all that remained of pre-war Pozieres. The German trenches had also been obliterated, forcing the front-line units to take cover in shell craters that provided some concealment from the constant bombardment.

At 12:30 am on July 23, the Australian Division attacked Pozieres, executing a well-thought-plan by its competent and experienced commander, Maj. Gen. H.B. Walker. By dawn the Australians had captured what was left of the German trenches and most of the village. For the next three days, they fought off numerous enemy counterattacks, suffering severe casualties from some of the most concentrated German artillery barrages of the entire war. In three days of intense combat, the division suffered 5,286 casualties. The fighting at Pozieres was reputed to be the toughest single battle in which Australian forces had ever been involved—the 17th Battalion alone used more than 15,000 hand grenades in clearing the last Germans from the village. The carnage was so great that for months afterward one Australian battalion, the 24th, could identify its old trenches by the half-buried bodies of its comrades, still displaying their red-and-white shoulder patches.

Jacka Discovered He had Only 7 Unwounded Men Left in His Command

Now that the village and ridge had been captured, the Australians had to hold it. This task was given to the 4th Division. Jacka and his platoon took up position in a section of trench known as the Elbow, 600 meters east of the village. After extensive artillery bombardment, the Germans atttacked with five battalions. The enemy high command had directed that Pozieres be retaken regardless of the cost. For Jacka, the first sign that his unit was under imminent attack came when two German stick grenades bounced down the stairs of the dugout, exploding and wounding two of his men. Jacka charged up the stairs, shooting and killing the lone German sentry left to guard that section of the line. The rest of the Germans had already swept over the trenches occupied by Jacka and his comrades.

As Jacka took stock of the situation, he found that he had only seven unwounded men left in his command. He told them they would have to break through the advancing German force and link up with the rest of the battalion west of Pozieres. In the dim light, moments before he was about to give the signal to climb out of their trench, Jacka saw more than 150 Germans casually walking over the smoking battlefield, heading directly toward him with 40 Australian prisoners in tow from the 48th Battalion. Thinking quickly, he told his men to lie down and wait for his signal to attack—eight Australians against 150 Germans.

When the lead Germans passed over the trench, Jacka leapt up and charged into their midst, his seven men right behind him. So surprised were the Germans by this threat that had literally popped up out of the ground that half the enemy dropped their weapons and threw up their arms in surrender, believing they had been attacked by a unit at least as large as their own. The Australian prisoners happily picked up the fallen weapons and joined the fight, along with Australians from other outposts along the Elbow and the front-line trenches.

Jacka’s Heroic Stand

Led by Jacka and Sergeant C.H. Beck of the 48th Battalion, the Aussies engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat with rifles, bayonets, and even fists. Jacka and his men were all wounded but continued to fight. Jacka personally killed between 12 and 20 Germans before the rest surrendered. He had been wounded seven times himself and collapsed as soon as the fight had been won. In the confusion, he was left for dead on the battlefield. When he regained consciousness, he was forced to crawl back to friendly lines, where he was found by stretcher-bearers roaming the battlefield looking for casualties. Barely alive, Jacka was evacuated to England and spent the next four months recovering. For his pains he was awarded the Military Cross, but many observers felt that he should have received a second Victoria Cross. Official Australian war historian C.E.W. Bean, who was at Pozieres during the attack, wrote later that Jacka’s feat “stands as the most dramatic and effective act of individual audacity in the history of the Australian Imperial Force.”

As one of the best-known and most highly decorated soldiers in the AIF, Jacka was asked by the government to return to Australia and assist in the war effort on the home front. True to form, he refused the cushy duty and insisted on returning to his unit, rejoining the 14th Battalion on December 9, 1916. Their war was far from over. In April 1917, the brigade was ordered to attack Bullecourt in support of the British 5th Army attack on Arras. Newly promoted to captain, Jacka was now the battalion intelligence officer, and he went out on one-man patrol into no-man’s-land to reconnoiter enemy trenches. While searching, he found a sunken road 300 meters in front of the current Australian position. The 4th Brigade moved into the new positon, thus avoiding a heavy German artillery barrage and saving hundreds of lives.

The next night, Jacka led a small patrol near Bullecourt. Ordering his men to take cover while he moved forwad alone to inspect German barbed wire obstacles, Jacka was forced to lie prone while a German patrol passed nearby. He found that much of the wire had not been cut by Allied artillery as previously believed. Returning to his own lines, Jacka sought out brigade commander Brig. Gen. C.H. Brand and warned him in no uncertain terms that the wire had not been cut and that if the Allied attack proceeded as planned, the division would suffer heavy casualties and the attack would certainly fail.

Brand and Jacka had clashed several times during the past year. Jacka had been very vocal about the lack of proper planning and the inadequate time allowed to train new soldiers. He pointed out that the orders received from headquarters were often unrealistic and utterly mistaken. Brand ignored Jacka’s new protestations and ordered the attack to go ahead. As Jacka had warned, the attack at Bullecourt, although initially successful in penetrating German lines, ended in heavy casualties and gained no additional ground. A total of 2,339 men were lost, nearly 2,000 being cut off and taken prisoner within German positions. Jacka, who had made several more trips into no-man’s-land to lay strips of tape for the men to follow on their advance and then personally guided each of the supporting British tanks into position, was awarded a bar to his Military Cross. Once again, those who had witnessed his actions felt that he should have received another Victoria Cross.

Jacka saw continuous service on the Western Front for another 13 months. He took command of D Company, 14th Battalion, and at the Battle of Messines he led his company in a successful attack that cap tured three enemy machine gun nests and an artillery position. Amazingly, while many of his peers were killed, Jacka managed to survive the deadly attrition in France and Belgium. In July 1917 he was wounded again, shot in the leg by a sniper, and evacuated to England. Once more he insisted on being allowed to return to France. During the subsequent fighting at Polygon Wood, Jacka’s company captured its objective and beat back several determined German counterattacks. He was recommended for the Distinguished Service Order, but headquarters did not act upon the recommendation. Many of Jacka’s fellow soldiers believed that the failure was retribution for his critical report on the affair at Bullecourt the previous year.

Australia’s Greatest Warrior

Jacka’s luck held until May 15, 1918, when he was shelled by mustard gas outside the village of Villers Bretonneux. His condition was so serious that he had to be evacuated to England for a third time, where he underwent two major operations to save his life. He was still recovering when the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, ending the war. He was among the last Australian officers repatriated from Europe, finally arriving in Melbourne in mid-October 1919 to a hero’s welcome that he tried hard to avoid.

Jacka was discharged from the AIF in Januay 1920. He went into private business with two other former officers, importing and selling electrical goods. When the Depression struck in 1929, his business collapsed. That same year, he was elected to the St. Kilda Council and later became mayor of the town, where he spent much of his time and energy seeing to the welfare of the unemployed in his district. Shortly after a council meeting on December 14, 1931, Jacka collapsed from exhaustion and was admitted to Caulfield Military Hospital.

To his many visitors, Jacka looked as though he were already dead. Although only 39, his three years in the trenches and nearly 20 wounds had taken their toll. On January 17, 1932, one week after his 39th birthday, Jacka died. He was buried with full military honors in St. Kilda Cemetery, wth eight other Victoria Cross winners acting as pallbearers. An estimated 50,000 people lined the streets as the gun carriage bearing Jacka’s body passed en route to the cemetery. A commemorative service is still held every January 17 in St. Kilda to honor the memory of Australia’s greatest warrior.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments