By Bob Bergin

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was America’s first strategic intelligence organization. President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized its establishment on June 13, 1942, six months after World War II began, to collect and analyze strategic intelligence and to conduct special services, including subversion, sabotage, and psychological warfare.

The OSS was conceived, organized, and led by General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, a New York lawyer and hero of World War I. The OSS attracted some very imaginative, capable, and colorful personalities who did incredible things during the war. Among them was a young journalist, Elizabeth P. McIntosh, who lived in Hawaii and was fascinated by Japanese culture.

After Pearl Harbor, she was ready to go off to a war zone as a correspondent. She was having problems getting overseas—until she met a man from the OSS.

Tell us about your early life.

EPM: My family moved to Hawaii in 1925. I started school in Honolulu, at a missionary school, a fine place where they taught you Latin and French and how to write. I went to university in Hawaii for a year, and then to the University of Washington. I graduated from the school of journalism and came back to Hawaii to start my career as a journalist.

Your first jobs were with newspapers?

EPM: My father was the sports editor at the Honolulu Advertiser. He got me a job writing sports. I didn’t like it very much and went over to feature work. I covered the waterfront, which was great fun then. There were all kinds of people coming in on boats in those days. That’s where I started my real writing career. There was a fellow named Alexander MacDonald at the newspaper then, covering the police beat. His desk was right in front of mine in the city room. We got friendly, and in time got married. We had a wonderful marriage for years, until the war came along. [MacDonald was a Naval Reserve officer who went on active duty and was later recruited into the OSS. At the end of the war, he accepted the Japanese surrender in Bangkok. He stayed on in Thailand and founded the prestigious English-language newspaper, the Bangkok Post.]

Did you share the same interest in Japanese culture?

EPM: Both of us wanted to go there to get jobs with newspapers or with the AP or UPI. We thought it would be great to speak Japanese. We moved in with a Japanese family and learned the language at night while we had dinner with the family. It was a completely Japanese home, and we really got to know the culture. We learned to speak Japanese, and Alex even learned how to write it. We stayed with the family until Pearl Harbor. At that point everything changed.

Where were you on Pearl Harbor day?

EPM: We had a house across the island from Honolulu, a place called KoKo Head. It was up in the mountains, overlooking a lagoon. The morning of December 7, Alex was still sleeping. It was around 7 o’clock, I was making breakfast and had the radio on, listening to a choir. All of a sudden the announcer broke in and said, “The Islands are under attack. This is the real McCoy.” And then the choir came back on. I wondered what that was all about.

The phone rang. It was “Hump” Campbell, my photographer, who lived nearby. He said something was going on at Pearl and the office wanted us to cover it. Hump was working for the Scripps-Howard news syndicate. I worked for them part-time and also worked for a newspaper in Honolulu. I drove in with him. It seemed like a regular Sunday, people walking dogs, playing golf, going to church, until we got closer to Honolulu. We passed an open-air market that had been hit by something. It was demolished. There were Christmas wrappings and toys all over the place, and in the middle of it all was this little Japanese boy, having a wonderful time playing with all this stuff. He had a big smile on his face. “This would make a great picture,” Hump said, “but the kid is too happy. Would you do something about that?” I went over and pinched him. He started to cry, and Hump got a wonderful picture that was used in Life magazine.

Hump got into Pearl Harbor, but they wouldn’t let me in because I was a woman. I went to the hospital that covered Hickam Field, where they were bringing in the badly wounded. I still remember one little dead girl. She still had a jump rope in her hands, just the wooden handles; the rope was burned away. We had only a few doctors; most were at Pearl. I worked there all day. That night, people were afraid to go home because of rumors that the Japanese were going to land. About 10 of them [refugees] came home with me to be safe.

What kind of work did you do after the attack?

EPM: I interviewed people coming in from different parts of the Pacific. A group from one of the islands included a Catholic priest, who had a good story. When the men he was with came under fire, they set up a line to pass ammunition from one to the other and on to the guns. The priest got in the line with his black suit and collar still on. Somebody yelled, “Father, you’re not supposed to be doing this.” He yelled back, “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition!” I wrote that up. It was where that song came from.

“It was Called “Oh So Social” and “Oh, So Secret.” And it was Really Quite a Secretive Organization.”

What were your career aspirations at the time?

EMP: I wanted to go overseas like some of the other correspondents, who were getting into the war zones, but somehow they wouldn’t let me go. Scripps-Howard decided to send me to Washington instead, to cover the White House.

Did you have a specific area to cover?

EPM: Mrs. Roosevelt was my special interest. I covered everything that involved her and also wrote a weekly column called “Homefront Forecast” that was carried in all the Scripps-Howard newspapers. I had a lot of fun with that. It was also how I first met a person involved with OSS.

How did that come about?

EPM: I came across a story about a man who had invented a machine to cut sugar cane. Workers were all in uniform by now, and no one was left to cut cane. It sounded like a good story for Hawaii. I went to interview the man, and it turned out that he knew my father pretty well. We got talking, and I told him that I had studied Japanese and was disappointed that I never got there. He asked if I would like to work for the government. I said, “Only if they would promise to send me overseas.” He said, “I think we can do that.” He wouldn’t tell me what department he was with, only that he would send me some papers to fill out. It turned out he was on General Donovan’s staff. And that was how I got into OSS.

At the time did you have any idea what OSS was?

EPM: I had no idea, absolutely none. Nobody else did either. It was called “Oh So Social” and “Oh, So Secret.” And it was really quite a secretive organization.

Was it called “Oh So Social” because many of its people were coming from the upper strata of society?

EPM: Yes. General Donovan was a New York lawyer. His wife, Ruth, was a very wealthy woman. Donovan had to start OSS from scratch, and he needed people he knew and could trust. Ruth was able to get her friends involved, while the general called on his lawyer friends and others he knew. Because of that it was really quite upper class for a while. The ladies had all gone to very good schools like Vassar, and the men were mostly Ivy Leaguers. When you got to be a part of OSS and got to know them, it was a wonderful group.

How did the OSS come about?

EPM: The president had named Donovan the Coordinator of Information (COI) in July 1941. This was the first U.S. attempt to put espionage, propaganda, and related activities under a centralized agency. The OSS grew out of that. Some of the things under the COI, like the overt propaganda, didn’t mesh with the secret stuff that Donovan really wanted to do. The overt COI operations were transferred to the Office of War Information, and OSS was established in June 1942 to provide strategic intelligence and “special services,” which would include guerrilla and psychological warfare.

Donovan traveled around Europe a lot before the war, trying to find out what was going on. He was very interested in intelligence, and he spent a lot of time with the British. He knew William Stephenson, the man in charge of British Intelligence in New York. His office was near Donovan’s, and the two of them were quite close. It was from his British contacts that Donovan got the idea on how to set up the OSS. He used these associations to convince the president that we should have a separate organization to do that kind of work, and that it should be called the Office of Strategic Services. It was rather a good name for it.

Donovan was a Republican, but he had direct access to FDR. How did that come about?

EPM: Donovan and FDR got on awfully well together. The president was interested in a lot of different things. Donovan had a great personality and was full of good ideas. I think Donovan influenced the president with his ability, his thinking, and his planning, all of which appealed to Roosevelt.

Donovan was also one of America’s most decorated soldiers. He had received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

EPM: Donovan had a very fine experience in World War I. He was tremendously brave. That’s where his name “Wild Bill” came from. He had the reputation for being able to dash in when everyone else was hanging back and get them to go on. He earned the medal. General Douglas McArthur served in Europe at the same time, but it was Donovan who came back as the most decorated soldier of the war. In later years, we wondered if that was why McArthur didn’t like Donovan. The two never got on, and McArthur never let OSS operate in the Pacific Theater. Actually, OSS did sneak into the Philippines, but that was as far as we could get.

What was your first impression of Donovan?

EPM: I was terrified, but terribly impressed. He was not a physically impressive type, like General McArthur. I once described him as “penguin-shaped.” He said, “May God forgive you for that.” He had beautiful blue eyes; everyone remembered his blue eyes. In the OSS days you never really got to know him. There was a very military air about him. You would see him arrive at the office and walk up the steps—march up, really. He wouldn’t stop to talk, and you didn’t just go up to him. I never did get to know him in Washington, but only in later years.

Could you describe how the OSS was organized?

EPM: There were quite a few sections. The most important one was R&A, Research and Analysis. R&A acquired all the information available and passed it on to the other OSS groups that could use it. I was in Morale Operations (MO). We did subversive work to try to change peoples’ minds. Today we would call that “disinformation.” R&A gave MO things we might be able to use. From R&A, the SO or Special Operations people would find out, for example, where the Germans were building a new factory, and then SO would do something about it. SI, or Secret Intelligence, collected intelligence and depended on R&A to identify what facts were needed in the areas that SI was trying to infiltrate. There were other groups, like MU, the Maritime Unit, that worked the small boats out in the Adriatic, and later in the Pacific. And, of course, there was a Commo unit that handled all OSS communications and dealt with cryptology.

“Japanese Soldiers had Always Been Taught Never to Surrender, but to Fight to the End and Die for the Emperor. That Took its Toll on a lot of our People.”

There was an OSS group called X2, which sounds very mysterious.

EPM: It was. No one could really talk to them. They were very secret. They were doing top-level stuff that nobody really should know about, and we never did.

What were your duties while you were stationed in Washington?

EPM: Mostly I was training to go overseas. A lot of the training was done at the Congressional Country Club in suburban Maryland. I learned to shoot there. Some of our men worked at blowing up things on the greens and made a mess of the club. After the war, when OSS made restitution, one of the bills was for “footprints on the ceiling.” The story was that our men were billeted in one of the beautiful houses that are still used today for special events. There were layers of cots, and the men on the top layer used the ceiling to balance themselves when they pulled their shoes on. There were other training areas where we were given assignments to tail people, or they would try to tail you. There was also a lot of psychological stuff, like trying to lure you to have a couple of drinks and break your cover. It was all kind of interesting fun.

When you finally went overseas, where were you initially assigned?

EPM: I was originally scheduled for China, but there were chiefs out there who didn’t want women assigned. They claimed there was no place to put us, which was not true. I got stuck in New Delhi for almost a year, but we were able to do a lot of work there.

What activities did you engage in during your time in New Delhi?

EPM: We had one particularly effective MO operation. Japanese soldiers had always been taught never to surrender, but to fight to the end and die for the emperor. That took its toll on a lot of our people. How could we get the Japanese to surrender when they were already in bad shape, surrounded, out of ammunition, out of food? At the time it just happened that there was a change in the Japanese cabinet, which gave us an idea. With the change in the government, why couldn’t there also be a change in the Japanese policy on surrender?

This fellow I worked with, Bill Magistretti, had studied in Japan before the war and was a wonderful Japanese scholar. We learned that the British had captured some orders that the Japanese had issued in Burma. We could use these orders as an example, and rewrite the text to say that under a new law enacted by the new cabinet the Japanese soldier could now surrender under certain conditions. We had everything we needed to do that, the chops, the paper, the inks. The problem was that there was no one who could help us write the order in the official Japanese language.

Then we heard about a Japanese prisoner who the British were holding at the Red Fort in old Delhi. He was a very educated man, which was very unusual for a prisoner. We arranged to see him. The Red Fort was quite a place. The prisoner was sitting in this room, in a yellow outfit, looking out a window. He wouldn’t even look at us when we walked in. Then Bill said something in Japanese, and the man turned around, and this funny look came over his face. “Biru!” he said, “Biru Magistretti!” It was amazing! This Japanese prisoner was a friend of Bill’s. They had been in college together in Tokyo. I just couldn’t get over it—old friends meeting like that. We explained what we wanted and eventually he agreed that what we wanted was also the best for his country. He wrote the order for us.

So we had the order. Now, how do we get it back into the Japanese chain of command? Colonel Ray Peers, the commander of OSS Detachment 101, came into town, and we met him at a party. Detachment 101 was running guerrilla operations in north Burma. We told him about our idea and asked if he could help us. He reacted coldly at first, but as we told him more, he began to get interested. He finally just grabbed the order and said, “I’ll take care of it for you.” And he did.

The rest of the operation was kind of gruesome. Colonel Peers had some tribal Kachin guerrillas working for him in Burma. One of them knew the trails the Japanese couriers used to move through the jungle. The Kachin waylaid a courier, killed him, and put our order in his pouch. Then the Kachin went on to the next Japanese camp and told them that someone had killed their courier. The Japanese went tearing back—the Kachin with them—found the courier, and looked through all the stuff in his pouch. According to the Kachin’s report, when the Japanese came across the order, they got excited about it and discussed it.

Much later we heard that as the fighting in north Burma went on, it became less desperate. Japanese soldiers were surrendering now, not fighting to the very end anymore. It seemed our operation had worked. Bill and I were both very pleased about that.

One of your books says that you were involved in an interesting operation with postcards in New Delhi.

EPM: That one was fun. The British in Burma found a big cache of postcards that Japanese soldiers had written home and had already gone through the Japanese censors. They were all written in pencil, and in very simple Japanese. So, Bill and I gathered a bunch of our Nisei friends, some of whom were friends of mine from Hawaii and all in OSS with us now. We got together at the office after hours, erased some of the messages, and put in new ones, like, “The emperor has let us down, we are fighting with no food, no ammunition.” We wanted to show the total disillusionment of the Japanese soldiers in Burma. Or else we would say things like, “I found a beautiful Burmese lady, mom, and I won’t be coming home.” We had more fun just thinking these things up. We got the cards back into the Japanese system and off to Japan. We don’t know what happened there, but sometime after this, they did change their government. We hoped our postcards helped a little bit with that.

What kind of relationship did you have with the British in New Delhi?

EPM: The British had everything we needed to do our MO operations. They had printing presses and all different kinds of type. We kept ordering that stuff from the States, but it never seemed to arrive, or if it did it went to the wrong place. We were just strapped for things that we needed to get our job done, and the Brits had it all. At first they were cool to us. They didn’t really want to help us, but we worked on them.

“We had Figured out That the Way to Get Our Packets of Information Ashore was to Float Them in, Inside Inflated Condoms.”

Your job was to get what you needed from the British?

EPM: We had to use their stuff to do our job. In return, we had to exchange information with the Brits, tell them a bit about what we were doing. OSS did not want us to tell them too much. It was a funny setup. They were our Allies. At least that was the theory I worked on, and it worked out pretty well.

Donovan visited Delhi. Did you get to see him there?

EPM: Only in the distance. But there was another time when I did get to see him closer. We were working on an MO operation in Ceylon, trying to get some information to the Indonesians. We needed a way to do it. One of my OSS friends in Ceylon, Jane Foster, had a friend in the British Navy who had access to a submarine and was willing to help us. We had figured out that the way to get our packets of information ashore was to float them in, inside inflated condoms. We were all in the MO shop one day, preparing the packets. There were condoms all over the place. All of a sudden somebody shouted, “A-ten-shun!” The door opened and in walked General Donovan. He took one look at us and what we were doing, smiled, very faintly, then turned and left. And that was all I ever saw of him overseas.

How did your transfer to China come about?

EPM: They finally opened up China for women. I flew there from India over the Hump. It was a terrible ride, about three hours of storms and lightning and jagged cliffs all around us. You could look way down below and see snow, and on it, like little crosses, the planes that hadn’t made it. And sitting there across from me was this girl, unconcerned, reading a book. She did that all the way over, and I just hated her. It was Julia Child, who later became the famous TV chef. We finally got to China, and Julia was the first out. She looked around very calmly, at the pagoda in the background, at the blue-coated coolies. “Oh, it looks just like China,” she said in that sort of warble she had. In those days she didn’t know how to boil an egg.

What was the city of Kunming like?

EPM: Today, Kunming is a fine city. Back then it was just a small town, like an outpost in the Wild West. There were a lot of pack animals around and people coming in from the hills. It was an old walled city, and there really was not much of anything to do. There were a couple of French restaurants because of the French who used to come up from Indochina. The American presence was very big, but we kept in our own compounds. We lived in what we called “the girl’s house,” which was nice. Once there was a little war between the local Chinese, and some came in and used our balcony to shoot from. My dog got away, and when I ran out after him they shot at me too. A jeep came and got us every morning and took us to the OSS compound that was surrounded by mud walls and sentries. The MO shack was a kind of mud house. But living wasn’t bad. We had good food, but you couldn’t get things like liquor, which they didn’t think was worth sending over the Hump. We survived and worked hard.

We didn’t mingle much with the Chinese people, which was too bad. I had a little dog, and I liked to go walking. I met the most interesting people. I couldn’t speak Chinese, and they had no English, but we got on all right. I remember a funny old man once, sitting there with a fire going. He was eating something. It was kind of crackling. He handed me chopsticks and invited me to join him. They were nice little things—didn’t taste bad at all. I asked what they were. He picked up a fresh one and showed me. It was a grasshopper. This was the sort of thing you did when you went on walks by yourself.

How did your MO work in China compare with what you did in New Delhi?

EPM: In China MO mainly sent things out to OSS people in the field, and they would turn it over to the Chinese who worked with them. In Kunming, we mainly provided the ideas about how to handle the problems that we wanted to influence. For example, the Chinese were asked by the Japanese to join their kamikaze corps. The Chinese really didn’t think that becoming a kamikaze was such a great idea, and we were able to play off that pretty well. In China MO wasn’t as much work as it was in Delhi because a lot of the practical aspects of it were done by the Chinese our field people were working with.

The end of the war came, and everything broke up. Most went home. Some of us went on to Shanghai, where we had a headquarters for a while. OSS was asked to carry out mercy missions at the end that were very important. OSS teams were sent out to locate Allied POWs all over China and other parts of Asia. Eventually, all of us came back to the States and were discharged. I went to work as a writer for a publication in New York City.

“She was Known to the Gestapo, Which put out an Order for Her Arrest. She Eluded Them by Disguising Herself as an Old Peasant who Herded Cows and Goats.”

OSS had some wonderful personalities who did incredible things during the war. In your book, Sisterhood of Spies, you tell the stories of some of the women of the OSS. Who among them most stands out?

EPM: It would be “The Limping Lady,” Virginia Hall. She was a great woman. Before the war, she was working in Turkey for our State Department when she had a hunting accident. They had to amputate her leg, and State said, “You can’t work for us anymore, you don’t have a leg.” When the war broke out, she was recruited by Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and sent to France, ostensibly as the stringer for a U.S. newspaper, but secretly to set up resistance networks. When it became too dangerous for her and SOE ordered her out of France, she walked across the Pyrenees into Spain—in winter. When she got back to London, she transferred to OSS and went back [to France] to organize sabotage and resistance groups before D-Day. She was known to the Gestapo, which put out an order for her arrest. She eluded them by disguising herself as an old peasant who herded cows and goats. She did a magnificent job under difficult and very dangerous conditions.

How well did you get to know Donovan after the war?

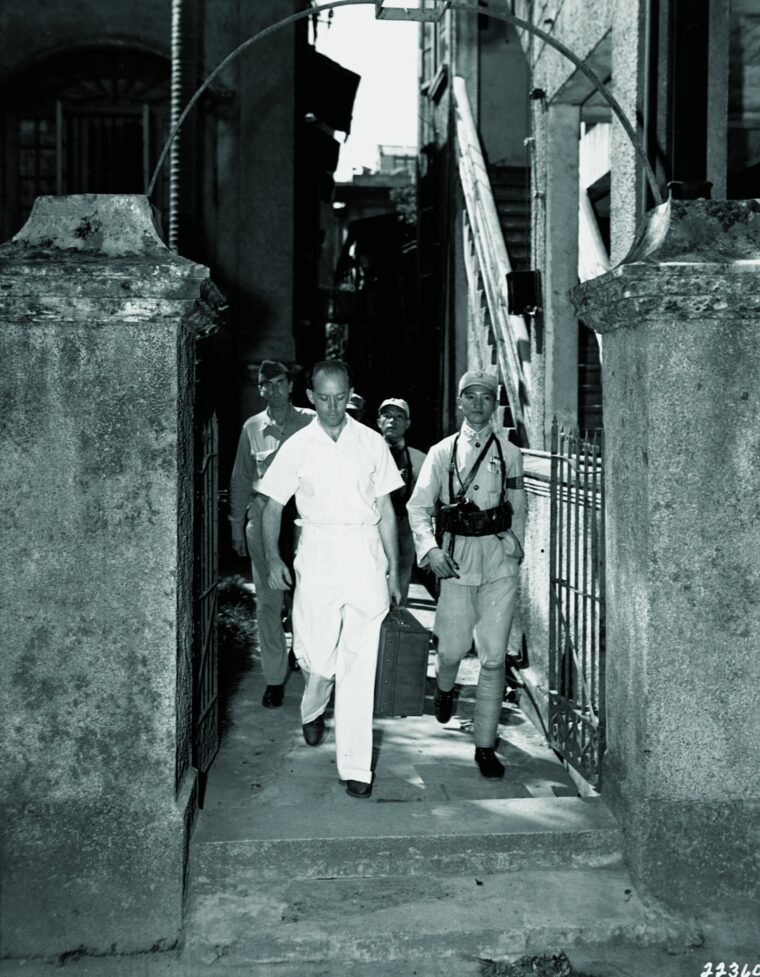

EPM: I was married to Richard Heppner, who had been a member of Donovan’s law firm before the war. He became head of OSS in China and after the war went back to work with Donovan again. Alex MacDonald and I had drifted apart. He stayed in Bangkok and started a newspaper there; I wanted to get home and do some writing. We had a very amicable separation and stayed in touch until he died in 2001. I met Dick Heppner again, back in New York. We got married, and that was how I got to know Donovan. In 1950, I was with them in Hong Kong, when the two of them were trying to get back a fleet of airplanes that General Claire Chennault had bought from Chiang Kai-shek, but were claimed by the Communists. That’s when I got to know Donovan pretty well.

We had a wonderful time in Hong Kong. Donovan loved to go shopping. I can remember having tea with him, and he would excuse himself and go out on the balcony and talk with some strange man in the shadows. He would come back and say it was someone from mainland China who had come to bring him up to date on what was going on. He was still in touch with the underground folks. He was quite a guy.

Donovan was out of intelligence work by then, wasn’t he?

EPM: When the war ended, OSS was disbanded and Donovan went back to civilian life. He stayed involved for a little while, but then they established the CIA, and Allen Dulles got the job. Donovan would have liked it, but President Roosevelt was long gone, and there was a lot of political maneuvering going on. Donovan returned to his law practice in New York.

Did you eventually come back to intelligence?

EPM: It was after Dick died unexpectedly, and I had to go back to work. I went to Allen Dulles and asked if he could give me a job. He said, “Where do you want to go?” I said, “Japan.” He said, “Okay, when did you want to go?”

When you finally got to Japan, was it all you expected?

EPM: I enjoyed every minute of it. It was terrific.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments