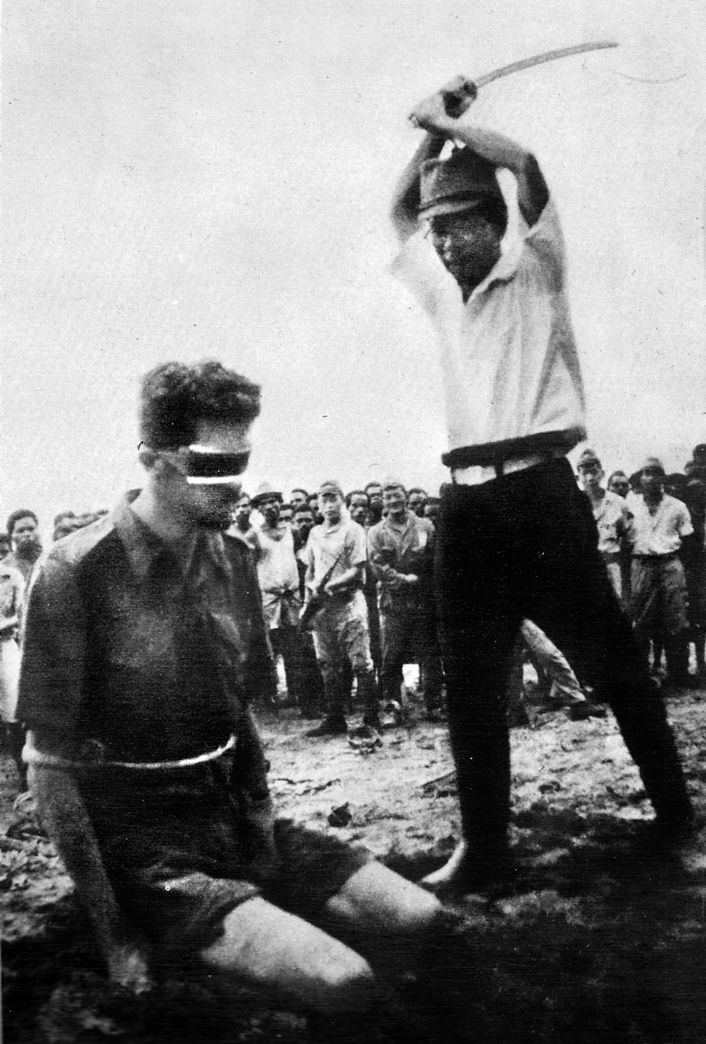

The photograph is brutal, harsh, and unsettling. The death of Sergeant Leonard George Siffleet occurred on October 24, 1943. Eighty years ago, Siffleet was bound and blindfolded, transported to the beach at Aitape, New Guinea, after two weeks of torture and mistreatment at the hands of his Japanese captors.

Moments later, Japanese naval officer Yasuno Chikao raised a samurai sword and beheaded the Australian Commando before an audience of fellow military personnel and native tribesmen who were in league with the Japanese. The stark image of Siffleet’s last moment on Earth has become an iconic representation of the inhumanity man often has for man. Chikao had ordered a private to take a photo of the execution, probably as a macabre personal memento of the event.

Siffleet was 27 years old at the time and had served with the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Born on January 14, 1916, in Gunnedah, New South Wales, Australia, he had hopes of becoming a police officer but was denied due to problems with his eyesight. He was summoned to join the militia in 1940 and served briefly. Less than a year later, Siffleet volunteered for the Second Australian Imperial Force.

After training in radio communications, Siffleet was detailed to the Services Reconnaissance Department (SRD), a component of the Allied Intelligence Bureau. Stationed in Melbourne, he soon transferred to Z Special Unit, working with the Dutch section of the SRD. In May 1943, he was promoted to sergeant and transferred to M Special Unit, perhaps specifically to participate in a hazardous mission behind Japanese lines in New Guinea to establish a coastwatching station.

The mission, codenamed Operation Whiting, was destined for the hills surrounding the town of Hollandia. Sergeant H.N. Staverman of the Royal Dutch Navy led the group of infiltrators that included Siffleet and two native Ambonese enlisted men, H. Pattiwal and M. Reharing. For two months, the group attempted to avoid contact with the Japanese or natives that were possibly assisting them. At one point Staverman and Pattiwal separated from the others and were captured. Pattiwal managed to escape, but Staverman was apparently killed.

Siffleet radioed a warning to a nearby Commando group, conducting concurrent Operation Locust, that there were natives sympathetic to the Japanese in the area. In early October the remaining members of Operation Whiting were taken prisoner, and no further communication was received from them. Reports indicate that the men were assaulted by 100 pro-Japanese natives, and in the brief fight that took place Siffleet shot and wounded one of the attackers.

After they were turned over to the Japanese, Siffleet, Pattiwal, and Reharing, were repeatedly questioned and beaten severely. On the afternoon of October 24, the prisoners were relocated to Aitape beach, where all three were beheaded. Rear Admiral Michiaki Kamada, commander of the 8th Japanese Fleet in the area, had given the execution order.

In the spring of 1944, the photo of Siffleet’s execution was taken from the body of a dead Japanese major by an American soldier, and records indicate that it is the only existing photo of a prisoner of war from a Western country being executed by a member of the Japanese military. Yasuno Chikao’s fate is unknown. Admiral Kamada surrendered to Australian forces on September 8, 1945. He was tried for war crimes, and hanged on October 18, 1947.

The fate of Siffleet, Pattiwal, and Reharing is but one of many such tragic wartime endings.

—Michael E. Haskew

A reminder as we approach August and the usual anniversary of atomic bomb whining, that we were fighting a war we did not start with an enemy with no rules. In social science, unlike physics, the reactions to events are rarely opposite but equal.