By Allyn Vannoy

Howard Linn was a member of the 492nd Bombardment Group—the “Hard Luck” group of the Eighth Air Force. It was a name well earned.

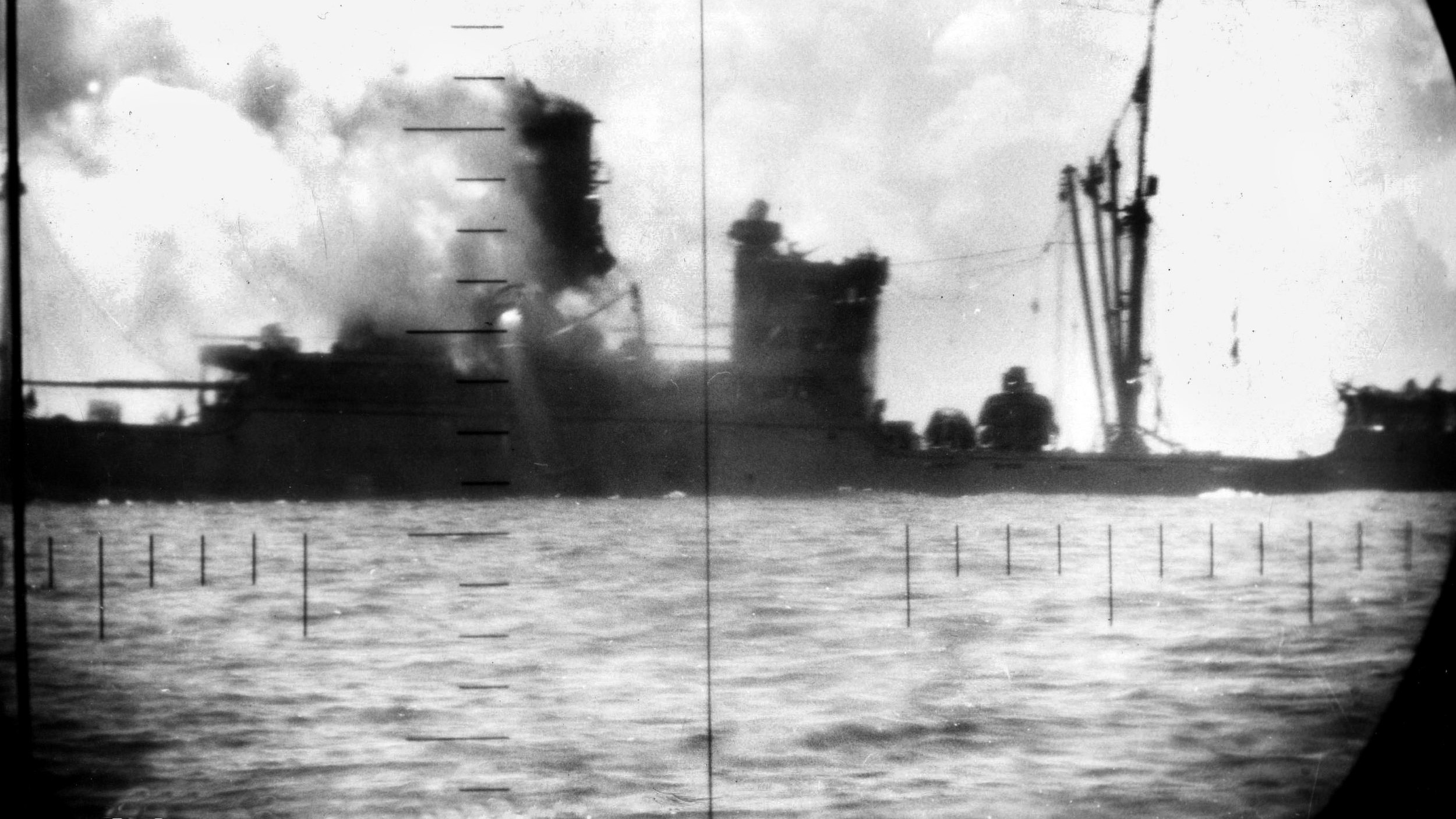

After hitting their target during a mission, Sergeant Linn’s formation of Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers of the 492nd Bomb Group was set upon by German Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighters. Linn prepared to engage the attacking aircraft from the left waist-gun position of his Liberator. Just making it to the skies over the Third Reich had been a long, hard journey for Linn, but making it back would be even harder.

While driving down the highway about four miles west of Radcliffe, a small town in central Iowa, on December 7, 1941, at about 1:30 pm, Howard Linn, along with his brother, Don, heard an announcement over the car radio that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. It was also Linn’s 19th birthday.

Well over a year later, on February 11, 1943, Linn’s draft number came up. After a series of physical exams and aptitude tests, he was happily surprised to be assigned to the U.S. Army Air Forces and sent to St. Petersburg, Florida. After basic training he was ordered to report to aerial-gunnery school in Fort Meyers, Florida. In May 1943, following gunnery school, he next reported to aircraft-mechanics school at Wichita Falls, Texas, after which he reported to Salt Lake City, Utah, where he was assigned to the flight crew of a B-24 Liberator. At Biggs Field, El Paso, Texas, Linn was assigned as the aircraft’s assistant engineer and as the left waist gunner. The assistant engineer served as a backup to the bomber’s flight engineer.

Linn’s fellow crew members included 2nd Lt. Howard E. Brantley, pilot; Thomas Magee, co-pilot; Thomas Kingston, navigator; Jack Rosey, bombardier; Raby White, flight engineer/top- turret gunner; Clifford Glasgow, right waist gunner; Clarence Majchrzak, radio operator; John Williams, tail gunner; and Willard Bristlin, ball-turret gunner.

In April 1944, Linn and his crewmates were flown, along with other bomber crews, to Herrington, Kansas, to pick up their new aircraft—a B-24J they nicknamed Silver Lady. After a few days of familiarization with the aircraft and additional training, they departed for Europe. The numbers of planes being sent across the Atlantic as replacements or to form new groups at the time was enormous. Because the northern route via Newfoundland and Iceland was so jammed with aircraft, they were directed to take the southern route. A series of legs took them from West Palm Beach, Florida, to Belie, British Guinea, and then to Natal, Brazil. They crossed the Atlantic, landing at Dakar, on the African coast, then flew over the Sahara Desert to Marrakesh, Morocco. The final leg took them over the ocean and around Fascist Spain to Scotland.

After transfer to their base at North Pickenham, England, they were assigned to the 859th Bomb Squadron of the 492nd Bomb Group, with the 2nd Air Division of the U.S. Eighth Air Force. The 492nd Bomb Group was one of the last groups deployed to England, arriving there with more experienced men in its ranks than any other group serving in the European Theater of Operation (ETO). They had more flying hours going into the war than most would have at war’s end. Many of them had been instructors, while others were veterans of anti-submarine patrol duties. Some had already completed a combat tour and had volunteered for a second. The group was the first ever to pass their POM (Preparation for Overseas Movement) inspection and depart ahead of schedule, fly as an unpainted aluminum bomber group, and reach England without losing any planes.

The first mission of the 492nd Bomb Group occurred on May 11, 1944, with the group assigned to hit the marshaling yard at Mulhouse, in eastern France near Switzerland. Thirty aircraft were dispatched, with all 30 hitting the target, but two were lost during the return leg of the mission. However, Linn’s aircraft was not assigned to go on the mission.

Linn’s crew saw their first mission the following day, May 12, as the group was sent to strike the oil refinery at Zeitz, well into Germany, some 20 miles south of Leipzig.

The next mission was to strike the Brunswick marshaling yards, deep in the heart of Germany, on May 19. Linn recalled: “We had to get up at about 3:00 am, dress and go to breakfast, then to [the] briefing room where there was a huge map of Europe. We were shown everything—the route to take, [our aircraft’s] place in [the] bomber formation, in squadron, group, wing and division. Also, the time we would cross the coast, the anti-aircraft flak we might have to fly through, and the types of German fighter planes we might encounter. We were told what kind of fighter-plane support we would have, whether it would be P-51s, P-38s, or P-47s or a combination of them. We were informed of what kind of bombs we would carry and how many, the target for today, and the approximate length of the mission. They then turned us loose to check out our parachutes, get on our flying suits and gloves, go to our bomber to do pre-flight checks—that meant checking all instruments and systems, starting our engines and checking the bomb load. Each gunner had to check his .50-caliber machine guns and also check his ammunition belt going to the machine gun, plug in his flying suit and see that the thermostat worked so you could turn up the heat at high altitude, because it was real cold up there with no heat in the bomber, and the waist doors were open with .50-caliber machine guns locked in position in the open door. Each B-24 had ten machine guns on board.”

After takeoff it took a long time to form up as the bombers climbed above the day’s over-cast. By the time they crossed the European coast, Linn had to transfer fuel from auxiliary tanks to the bomber’s main tanks. Though an electric pump was used, one had to carefully time the operation. Then Linn pulled the pins out of the nose fuses of the bombs in order to arm them.

The bombers encountered heavy flak over the continent. They changed course and alti-tude periodically so that the antiaircraft guns couldn’t zero-in on them. As the group made its way toward Brunswick, many of the airmen witnessed dogfights between the Luftwaffe fighters and their own escorts. The Germans used decoys in an effort to lure the Allied fighter protection away from the bomber groups.

As they approached the target, Linn recalled that the air was filled with black smoke, and he saw huge fires on the ground, the result of bombs dropped by aircraft ahead of his own. They dropped their bombs and then turned for home. An estimated 40 German fighters engaged the bombers of the 492nd. By day’s end, the group had lost eight of the 26 bombers dispatched. Only 19 had reached the target; 43 crewmen were killed, three wounded, and 34 taken prisoner.

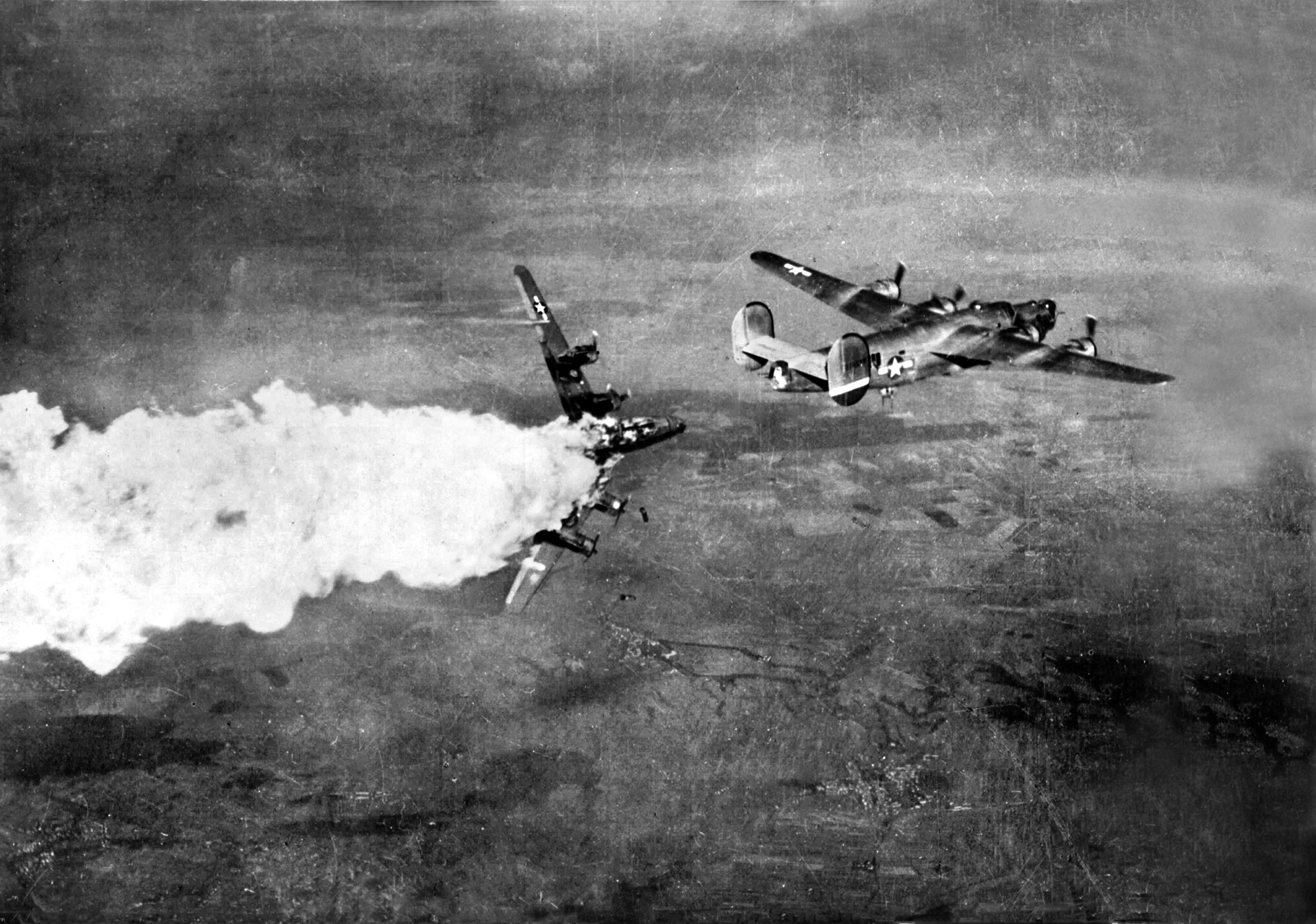

Linn noticed a large group of German Fw-190s flying above and to the left of their for-mation, out of range of the bomber’s machine guns. The fighters then flew around to the front of the formation and turned to make a head-on attack from “12 o’clock high.” Linn saw a B-24 of a friend get hit and watched it disappear from view without any parachutes appearing.

After passing through the formation, the German fighters went around and made another head-on attack. The No. 3 engine, on the right wing of Linn’s aircraft, was hit and burst into flames. The pilot or co-pilot initiated the engine’s fire extinguishers and feathered the prop in an effort to put out the fire.

Linn then noticed smoke coming out of the leading edge of the left wing and called the pilot, but Lieutenant Brantley reported that he was not able to see anything. The design of the Liberator had the wings of the B-24 opening into the fuselage just above the bomb bay, so that in a matter of seconds fire was coming out of the left wing and into the fuselage. Linn called the pilot again on the intercom and told him what was happening and of his concern that the fire must be close to the fuel tanks. The pilot asked him if he could get at it with a fire extinguisher.

Linn responded that there was no way he could reach the fire because it was in the wing. In moments the heat in the aft compartment was like an oven. Linn called the pilot once more and told him that they would have to get out because it was getting too hot. Linn told him that he was bailing out. He ripped off his throat microphone and oxygen mask, unplugged his electric flying suit, grabbed his chest pack parachute and snapped it onto his harness, opened the hatch in the floor of the aircraft, and dived out. Linn believed that three other members of the crew followed him out. After the tail gunner, John Williams, left the plane, it exploded and seemed to disintegrate right behind him.

After their first mission, some of the crew had become ill. As a result, on this mission three of the regular crew were replaced by substitutes drawn from other crews. Crew members that day included Lieutenant Brantley, pilot; Technical Sergeant Frank Collicchio, radio operator; Staff Sergeant Henry O. DeVisser, first engineer and top-turret gunner; Lieutenant Thomas J. Magee, co-pilot; Lieutenant Jack Rosey, bombardier; Lieutenant John H. Zahn, navigator; and Staff Sergeant Foster, ball-turret gunner, all of whom were killed. Survivors included John Williams, tail gunner; Clifford Glasgow, right-waist gunner; and Linn. Prior to the mission, Linn and DeVisser had agreed to switch off between duties as engineer (top-turret gunner) and waist gunner. As fate would have it, on this mission Linn was operating the left waist machine gun.

As Linn was making his free fall, he lay on his back and looked over his shoulder to see the clouds below him. He started to spin faster and faster until he raised one foot and lowered the other. Once he cleared the clouds, he could see the ground, still far below him. He waited until the trees appeared to be coming up fast before pulling his ripcord. The chute opened with a jolt. Moments later Linn impacted the ground hard.

He was fortunate to land in the clearing of a wooded area, but as he hurried to get out of his harness and parachute, he forgot to grab his army shoes, which he kept tied to his harness when flying. He ran about half a mile through the woods and then crawled under a brush pile. From time to time, he could hear voices, undoubtedly searching for the owner of the parachute. After it got dark, he moved from the brush pile and went deeper into the woods for the night.

The location where the bomber came down was about 1,000 yards east of the village of Niedernstöcken, near the Leine River, about 24 miles north of the city of Hannover, in an area of pastures and meadows. Decades later, people who lived in or near the village still recalled seeing three burned bodies described as “carbonized mummies” at the crash site. Three more bodies were found inside the crashed aircraft, and a seventh was found near the entrance to the pasture where the aircraft came down. This last body was the ball-turret gunner, who had come down without his chute, apparently blown out of the bomber. The villagers buried the bodies in the church cemetery. After the war they were removed by the U.S. Army to a military cemetery. The three who had bailed out of the aircraft were reported as coming down near the town of Stoeckendrebber. At dawn, Linn got rid of his flying helmet and took off the outside of his electric flying suit so that he just had on the inner liner. He had to continue wearing his flying boots since he didn’t have his shoes. He opened the escape kit he had been issued and took an inventory—compass, maps printed on a silk handkerchief, chocolate, and some medical items including mor-phine. Using the compass, he started west, sticking to the woods for cover. When he spotted a couple of windmills, he wondered if he had come down somewhere in Belgium or the Netherlands, but without a landmark or road signs the map was of little use.

About noon he came to a small village and decided to chance walking through it in the hope that there would be a sign that might help him get his bearings. He knew that there was an Underground movement in France and the Low Countries who would hide American and English airmen. In an effort to blend in, he lit up a cigarette and walked straight down the road through the village. He met a few people, also on foot, along the road and nodded a greeting to them and just kept going. As this seemed to work, he decided to keep going, unaware that German men always wore hats, and being bare headed, he stood out.

About two-thirds of the way through the village, a boy standing in the doorway of a house looked him over as he walked. When a motorcycle policeman came around a corner behind him, the boy ran into the street waving his arms to get the policeman’s attention. The boy pointed toward Linn, and the policeman wheeled about pulling up beside Linn. Captured!

The young man who tipped off the policeman while Linn was passing through the village of Rodewald, on May 20, 1944, was 15-year-old Wilfried Beerman. Linn and Beerman were re-acquainted 55 years later, and Beerman was still living in the same house. The two carried on communications for the next few years until Beerman’s death.

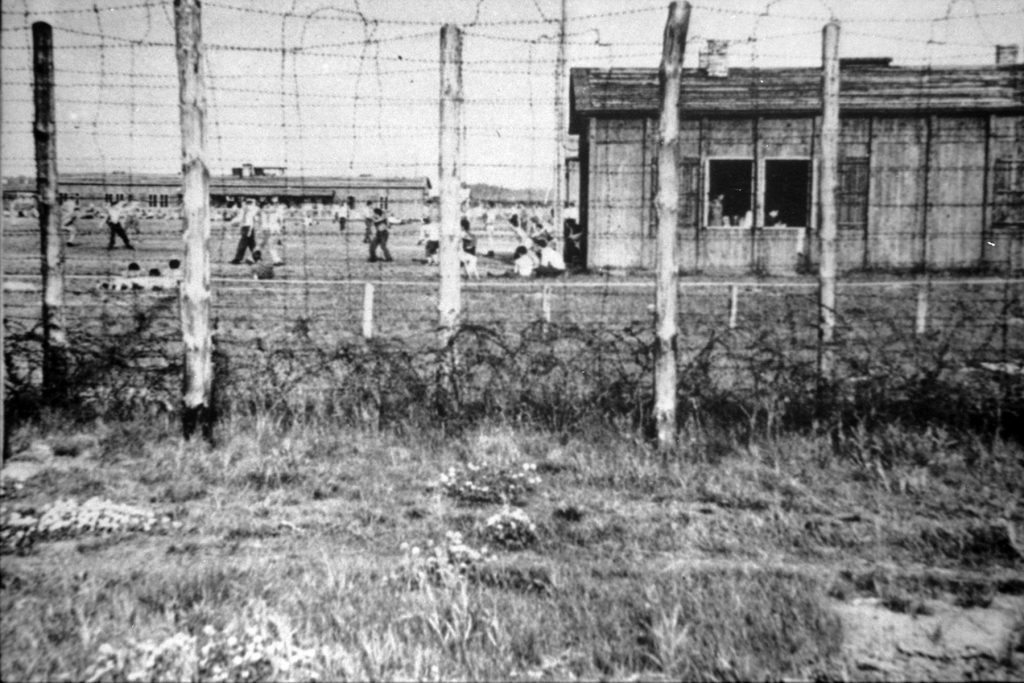

Linn was taken into the boy’s house, and some telephone calls were made. Then Linn was taken to an area in the village where French and Polish forced labor workers were held. Linn was placed in a barbed wire enclosure. Late in the afternoon a Luftwaffe officer picked him up and transported him to another camp about 20 miles away. The next morning, Linn and two other American flyers were taken to an interrogation center in Frankfurt, Germany. After all his personal possessions were confiscated, he was placed in a cold and damp six-by-six room with a small, barred window and a canvas cot. A couple of hours later he was taken to another room for questioning. His interrogator cursed him for providing only his name, rank, and serial number.

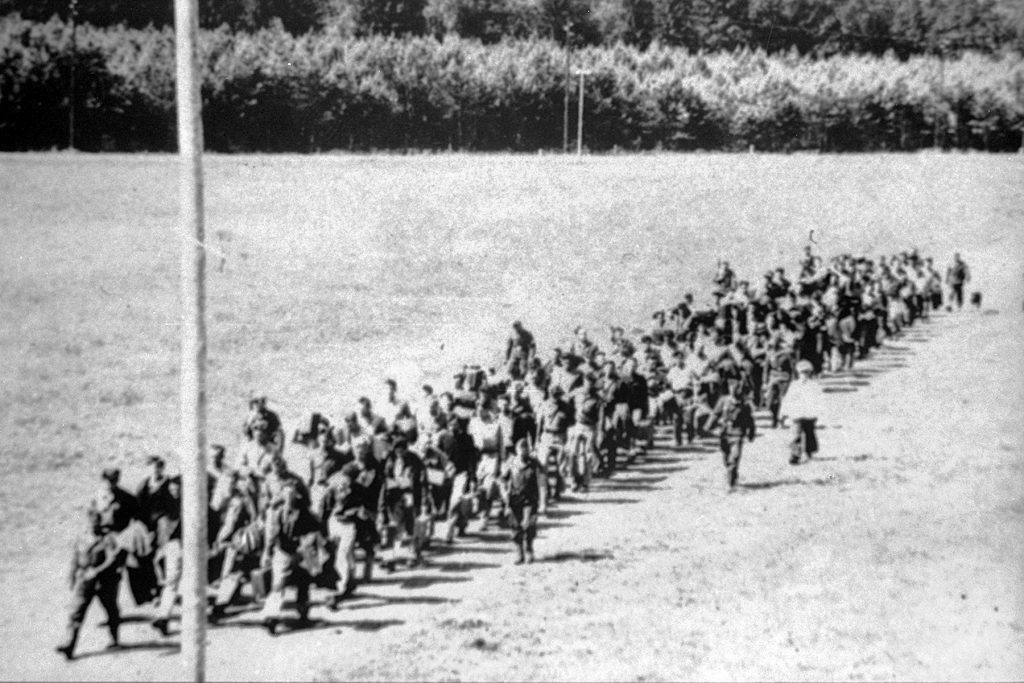

Linn was next packed into a railroad car with other POWs, each given a single loaf of dark, heavy sour bread to sustain them for the next four days. The train took them northeast to the town of Stettin. From there they were marched another 20 miles to Stalag Luft IV.

Stalag Luft IV, near Gross Tychow, Pomerania (present day Tychowo, Poland), was re-ported by the International Red Cross as generally bad. It was divided into five compounds separated by barbed wire fences, with the POWs housed in 40 wooden barrack huts, each containing 200 men. None of the huts were heated, with only five small iron stoves in the whole camp. Latrines were open-air, and there were no proper washing facilities. Medical facilities and supplies of food and clothing were also considered inadequate. The camp housed at one point 7,089 Americans and 886 POWs of other nationalities.

Each compound was enclosed by high barbed-wire fences with machine-gun towers every 200 feet, plus guard patrols. There was a warning rail about 30 feet inside the fence that represented the deadline—anyone crossing could be shot. A central latrine was built over a cement pit. Sixteen prisoners occupied a barracks room, and this increased later to 28, though there continued to be only 16 bunks to a room. The food was poor, usually consisting of barley cereal and ersatz coffee in the morning along with a ration of sour bread for the day, sometimes with a little jam. At noontime a thin soup with either dehydrated cabbage or dehydrated greens with a trace of meat was served. In the evening there were boiled potatoes with the skins on and coffee. The Red Cross was supposed to provide an 11-pound food parcel for each man once a week, but these usually ended up as a single parcel being shared by six to eight men. The parcels included a can of corned beef, a can of Spam, a tin of powdered milk, a small can of liverwurst, a condensed chocolate bar, a container of English crackers, a small bar of cheese, and seven packs of cigarettes.

A typical day in prison camp began with breakfast, then standing formation in front of the barracks. The commandant, a Luftwaffe officer, and his assistant, would count noses. If anyone moved or made any noise while this was being done, they would be required to stand in formation longer. About noon, one of the prisoners would go to the mess hall and get the soup to divide among the 10 rooms of prisoners in the barracks. During the late afternoon the process was repeated for the boiled potatoes. Once a month the Germans provided limburger cheese as a treat. Often it was found to have maggots in it, but most of the prisoners would pick the maggots out and eat the cheese.

In the late afternoon. the prisoners would have to stand in formation again for another nose count. Guards were always walking about the compound.

The prisoners resigned themselves to their circumstance. At dark, they were required to put wooden covers over the windows so that no light showed through—complying with black-out conditions. The door to each barracks was locked, and dogs were released into the compound for the night. All lighting was switched off by the Germans at 10 pm.

With lots of time on their hands, Linn noted that the prisoners never talked about their wives or girlfriend after lights out. They would lie in their bunks and describe their favorite foods. “It was enough to drive you nuts because everybody was so hungry,” he remembered.

The prisoners were also cursed with fleas. They would wake each morning to find any exposed skin covered with bite marks. Linn noted that some prisoners went so far as to take their mattress out and dump all the straw out on the ground and then put them back piece by piece in an effort to get rid of the fleas.

In order to have something to do, the prisoners made their own bats and balls. They formed a softball league with two teams from each barracks. They also passed the time reading books provided by the Red Cross or running bridge tournaments. Every evening someone would come around and read the news to the prisoners—how the war was going and what advances the Allies were making. The source of this information was not revealed. On Sundays there were worship services conducted by one of the POWs. Everything was done from memory, both hymns and scripture.

Many of the POWs would simply lie , aware that they would not survive. As a result, a ward was filled with men who suffered mental illness.

During late afternoons, hundreds of POWs would walk about the compound for exercise, just inside the warning wire. Linn recalled an afternoon when one of the POWs “lost it,” stepped over the warning wire, and headed for the barbed wire fence. The guards began yelling at him, but he kept going. Once at the fence he started climbing it. He was halfway up when a shot rang out, and he fell to the ground, dead. The guards rushed into the compound and ordered the POWs back inside their barracks.

About every two weeks the Germans would bring in a large tank on wheels, pulled by horses, similar to an LP tank, with Russian prisoners working it. They had a large hose, six to seven inches in diameter, attached at one end of the tank as the other end was dropped into the pit under the latrine. The tank was equipped with a pop-off value on top, about 12 inches in diameter and also had a place to pump gas into the tank. They would then ignite the gas resulting in a back blast forcing all the air out through the valve and resulting in a vacuum in the tank. It would then suck the contents of the pit into the tank. They would spread the contents on the nearby fields. Watching this operation was one of the few entertainments the prisoners had.

In mid-July 1944, the prisoners of Stalag Luft VI arrived at Linn’s camp, some 2,500 ad-ditional POWs. They had been evacuated from their camp near the Baltic Sea because of the approaching Soviet Army. These new arrivals were divided among the compounds. Shortly after these new POWs arrived, Linn came out of his barracks and spotted a fellow who looked familiar walking across the compound. It was Don Amundson, also from Radcliffe, Iowa, and a relative of Linn’s. They shared their experiences from the last few months. Amundson had been a gunner on a B-24 of the Fifteenth Air Force flying out of Italy, when he was shot down on his 13th mission.

For Christmas 1944, the camp commandant told the POWs that he would allow them to remain outside until midnight with the compound lights on, as long as they made no attempt to escape. The Germans also provided a little extra food. The prisoners spent the time singing Christmas carols.

Other events were not so joyous. A German electrician had been working on a transformer on a pole near the center of the camp when he came into contact with a hig-voltage wire and was killed, smoke rolling off him as he began turning black. When the POWs cheered the guards rushed into the compounds and forced them back into their barracks, locking them in for the rest of the day.

On another occasion several German fighters were training above the camp when one of them crashed. The POWs cheered the event, resulting in the guards charging in and making the POWs return to their barracks.

After supper one evening, one of the POWs, instead of going down the hall and out the front door of the barracks, opened the double windows in his room and jumped to the ground. A shot rang out, and he fell dead. The guard, some 70 feet away, claimed that the prisoner had made a face at him.

After some nine months, there were rumors that the camp would have to be evacuated because of the Soviet Army’s approach. Early on the morning of February 5, 1945, Linn and his fellow prisoners were told to prepare to leave the next day. The prisoners were allowed to take supplies and clothing from a stock of Red Cross parcels in a German warehouse. They packed everything they could carry. It was still winter, and conditions were harsh. They walked all day, then slept in barns or in the open in rain and snow. Guards and dogs kept a watchful eye on them.

The prisoners were marched westward, though sometimes they seemed to be wandering aimlessly. The men suffered from lice as a result of bedding down in barns on straw spread over manure, packed in like sardines. Many of the prisoners had dysentery. Linn was sick for three days, suffering from stomach cramps so badly that he felt that he wouldn’t make it. “I was lucky because I came out of it and never was sick again … for the rest of the forced march,” he said.

The barns where the prisoners stayed were at collective farms, and their meager food was cooked in huge vats that the forced laborers used to cook vegetables and grain for their livestock. The prisoners were served a soup of kohlrabi, cabbage, potatoes, or barley cereal, along with a small portion of sour, black bread. In the evenings they were given two boiled potatoes.

Linn recalled: “When we left Stalag Luft IV there were 2,000 POWs in my group, but by the time we got to an International [Red Cross] camp by Hannover, Germany, there were only 1,500 left.” Many of the men were so weak from dysentery or other illnesses that they were forced to fall out of the column. The Germans said that they had taken these men to hospitals, but shots were heard and these men were not seen again.

“We had been on the march for 52 days when we arrived at Hannover,” Linn continued. “Most everyone traveled in pairs, that way you had two army blankets, one below you and one above when you bedded down for the night, plus we had two overcoats to put over the top of us. Also there were two of us to share the body warmth when sleeping. We had walked as much as 30 kilometers in a day, about 18 miles, sometimes as little as 15 kilometers and there had been a day or two we laid over either because the weather was so bad or because the Germans didn’t know where to take us.”

The POWs were again forced to evacuate, this time ahead of the advancing British Army. When they passed through cities that had been heavily bombed and reduced to piles of rubble, Hitler Youth members would stand on the curb and spit on the POWs as they walked by. The improving spring weather during the latter part of March did make the ordeal somewhat easier. The POWs continued to move each day as they were squeezed between the Soviet and British armies. Then, toward the end of April, the guards began to disappear.

Linn continued his story: “At this time we could have taken off, but felt it was much safer to stay together. We were camped in a timber on May 2, 1945, [near Lauenburg, Germany] thirty-five days after leaving Hannover. We had been on the death march a total of 87 hard, ship-filled days. We had gone over 600 miles since evacuating Stalag Luft IV. It was a bright sunny morning … [when a] cheer went up when four English soldiers in a jeep rolled into camp. Our guards, that were left, quickly handed over their rifles.”

The former prisoners were told to head west. The next day they reached Allied lines. They discarded their tattered clothes and burned them, took showers, and were deloused. A few days later, they reached Brussels, Belgium, and boarded C-47 transports that took them to Camp Lucky Strike in France. Several days later they were trucked to the port of La Havre, boarded ship, and were carried across the Atlantic to Boston.

Howard Linn was Honorably Discharged on October 26, 1945. He returned to the family farm in Iowa, eventually married, and had a family.

“I look back at this experience … as a mixed blessing,” he reflected. It gave me a chance to sit back and see what is important in this life and what is not. All in all the Lord has blessed me with a good life for which I am thankful.”

In a final note, while the 492th Bomb Group had a superb record, it suffered more casualties and losses during its 67 missions in the 89 days it was operational, from May 11 through August 7, 1944, than any other B-24 group and was the first and only group in the ETO to be disbanded due to its high number of casualties. It lost 55 aircraft and 520 officers and men—234 killed in action, 26 wounded, 131 taken prisoner, and 129 interned in Sweden or Switzerland.

General James Doolittle, commander of the Eighth Air Force, and his staff dubbed the 492dn the Hard Luck Group. The high loss rate of the unit was believed due to the planes being unpainted—their gleaming silver bodies making them easier for the enemy to find as the sunlight reflected off them.

Although they found themselves without fighter protection on several occasions, they did not fail to fight their way to their targets.

Author Allyn Vannoy has written extensively on a variety of topics related to World War II. He resides in Hillsboro, Oregon.