By Michael E. Haskew

Only two years after the U.S. Army officially sanctioned the formation of an airborne arm, American paratroopers were committed to a vast offensive against Axis forces on the coast of French North Africa. Operation Torch, a highly complex endeavor scheduled for November 8, 1942, involved Allied forces landing at Casablanca, Algiers, and Oran.

Plans for airborne troops to participate in operations against Casablanca and Algiers were briefly considered and then dropped.

The Algerian port of Oran, however, had two nearby Vichy French airfields, Tafaraoui and La Senia. Just 230 miles east of the British bastion at Gibraltar, they included the only runways in western Algeria that were adequate for sustained operations, and Tafaraoui was the only one with a hard surface. Vichy fighter planes were within range of the Center Task Force, one of three poised to hit the North African beaches, which included 18,500 troops of the U.S. 1st Infantry and 1st Armored Divisions under Major General Lloyd Fredendall.

Tafaraoui was 15 miles south of Oran, and La Senia just five miles distant. To secure these airfields, remove the Vichy threat, and facilitate the introduction of reinforcements and supplies, it was decided that risking an airborne operation was worthwhile. The 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) was placed under Fredendall, and its 2nd Battalion was slated to make the first American combat jump in history.

The 509th had been authorized on March 14, 1941, originally as the 504th Parachute Infantry Battalion, and activated on October 5 of that year at Fort Benning, Georgia. In February 1942, the battalion relocated to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and joined the 503rd Parachute Infantry Battalion to form the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment. In June, the 503rd was detached for service in Scotland and became the first American airborne unit deployed overseas during World War II.

The American paratroopers trained with the British 1st Airborne Division, participating in the lowest large-scale parachute drop in history, from an altitude of just 143 feet. On November 2, 1942, less than a week prior to Operation Torch, the 503rd was redesignated as the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

Two months prior to Torch, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean Theater, gave the go-ahead for an airborne assault on Tafaraoui and La Senia. The 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR, the only American unit of its kind in Europe, was designated for the drop, and its delivery was assigned to the 60th Troop Carrier Group. The two units had been training together for about three weeks when the orders were received in early September.

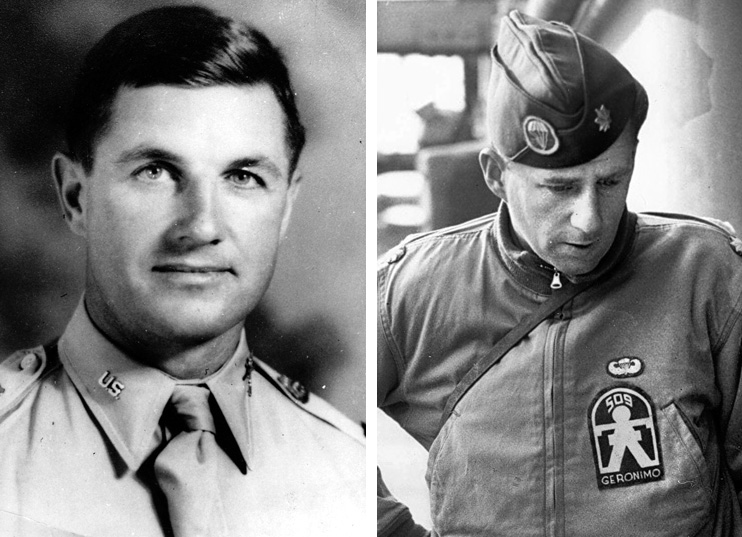

On September 12, a command group called the Parachute Task Force was established with Colonel William C. Bentley in charge. Bentley had served previously as an Army Air Forces attaché in Morocco and was familiar with area. A cadre of 77 officers and enlisted personnel formed the command structure of the Parachute Task Force, and Bentley was in command during the preliminary phase and while the paratroopers were in the air. Lieutenant Colonel Edson D. Raff commanded the 2nd Battalion, 509th, and went directly to General Mark W. Clark, a member of Eisenhower’s staff and a close friend of the supreme commander, to request that the paratroopers remain under his own direct command once they were on the ground.

Raff was a respected officer, who had trained his men relentlessly and earned the nickname “Little Caesar” for his hard-nosed command style and stocky build. Clark granted the request.

Some concerns were raised during the planning of the airborne operation, particularly by British Air Marshal William L. Welsh, the highest-ranking member of the air forces section of Eisenhower’s planning staff for Torch. Welsh recommended that the airborne troops should be held back and committed after the Torch landings during the drive to capture the Tunisian capital city of Tunis. His recommendation was discussed briefly, but the preparations went forward.

The first American airborne combat operation remains the longest mission of its kind in the history of warfare. To diminish the possibility of the airborne force being discovered by the Germans, the Douglas C-47 transport planes that were to carry the paratroopers had to be located as far from enemy intelligence agents, radar stations, and fighter bases in occupied France as possible. The fuel capacity of the C-47s, though, required the planes to be based as close as possible to North Africa. Survey crews scoured Land’s End at the southwestern tip of England and chose the small airfields at St. Eval and Predannack. The original force of 36 planes was increased to 39 and divided between the two bases.

Hazardous flight paths across Vichy France in the east or the open Atlantic Ocean in the west were quickly dismissed. The most direct route was through Spanish airspace. Although neutral, the Spanish government was viewed with suspicion. Its fascist head of state, Generalissimo Francisco Franco, was pro-German. Nevertheless, the airborne mission was approved to fly across Spain, a distance of 1,100 straight-line air miles. The flight was to be one-way, and the C-47s would land in the North African desert if airfields were unavailable.

Three days before the mission embarked, six Bristol Beaufighters based at Predannack and a flight of Supermarine Spitfires from Portreach were assigned as escorts. For most of its duration, the eight-hour flight would be conducted under the cover of darkness, which offered some protection from enemy eyes and antiaircraft defenses, although it also obscured landmarks and other visual navigational aids. A possible solution resided with the Royal Navy antiaircraft ship HMS Alynbank, equipped with a beacon that would begin sending radio signals from a position about 35 miles off the African coast near Oran at 11:30 on the night of November 7. The signal was to be broadcast at 440 kilocycles, a frequency that would simulate an Italian transmission. To help ensure success, as soon as the transport planes were visible at a distance of 20 miles the Alynbank would also begin flashing a V from its signal light.

As the transports crossed the North African coastline, they were also expected to pick up a radar signal planted near Tafaraoui by an agent code named Bantam. Bentley’s plane and those of group commanders and squadron leaders were to carry receivers known as “Rebecca,” that would enable them to home in on Bantam’s signal. Operatives on the ground might also fire flares to illuminate Tafaraoui once surprise was assured.

A complement of 531 paratroopers was to load and lift off into the afternoon sky at 5 p.m. on November 7, and drop near the target airfields at 1 a.m. La Senia was deemed the most difficult objective due to its shorter distance from Oran, and it was also the least valuable of the two airfields. Tafaraoui was an all-weather field and considered easier to capture. The flight path to Tafaraoui, across a large dry lake bed called the Sebka d’Oran, was also less likely to attract attention.

The parachute drop would take place over Tafaraoui, and once that objective was secured a company of the 2nd Battalion would march on La Senia, destroy its facilities and any planes on the ground, and withdraw. Another small force would disrupt Vichy communication lines near an airfield to the northeast at Lourmel. Once these missions were completed, the airborne force would concentrate at Tafaraoui and hold until relieved.

The mission of the 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR was nearly cancelled in late October after General Clark returned from a clandestine meeting with Vichy officials with promising news that the Torch landings might be unopposed. Eisenhower considered canceling the airdrop and saving the paratroopers as Air Marshal Welsh had suggested. Clark met with Bentley and Raff on October 28, and the three offered contingency plans to Eisenhower. Should negotiations prove fruitless and the Vichy French appeared likely to resist the invasion, the original “Plan A” would go into effect as the signal “Advance Alexis” was broadcast. If the Vichy French agreed to cooperate with the Allies, an alternative “Plan B” would be implemented with the broadcast of the signal “Advance Napoleon.” Plan B called for the airborne force to land in daylight on D-day at La Senia and stand ready for a mission against airfields in Tunisia.

Plan A, anticipating a hostile reception in Africa, was in effect until the afternoon of November 7. With planes and paratroopers assembled, the signal for Plan B, “Advance Napoleon,” was received. Takeoff was delayed for four hours to allow aircraft to land in daylight at La Senia. Some troopers had already been crammed into their planes with full combat loads for two hours when word reached them.

At 9:05 p.m., the first C-47s rose into the air and formed into four flights, a lead flight of nine planes and three more of 10 each. Final assembly took place above Portreach, and the force flew south on a heading of 225 degrees. Strong winds were encountered over the Bay of Biscay, where a turn was made to 177 degrees. Some planes fell behind the leaders, and as the wind speed increased there were more stragglers.

Cloud cover and rain squalls forced some planes to divert from their intended course, and when the formations neared the coast of Spain they encountered rough weather due to an incoming front that meteorologists had warned the pilots to expect. As the planes climbed to 10,000 feet to clear coastal mountains, some lost airspeed and fell further behind. Others attracted sporadic antiaircraft fire. The weather remained rough, and aircraft became widely scattered.

Cloud cover hampered attempts to navigate by the stars for the few planes that had American instruments for the purpose. In the confusion, several pilots became disoriented. One plane ran out of gas and landed at Gibraltar. Three others landed in Spanish Morocco, some 250 miles west of Oran. Two planes landed in French Morocco, and Vichy fighters either shot down or forced three more to land. Antiaircraft guns barked along the African coast, and those pilots that reached La Senia were surprised when they took more antiaircraft fire.

Those pilots who had managed to stay on course received little help from Alynbank, which was broadcasting on 460 kilocycles, not 440, its beacon unintelligible. On the ground at Tafaraoui, Bantam was unaware that Plan B was in effect. He expected the transports overhead at 1 a.m. and destroyed his radar equipment when none appeared.

Colonel Bentley and five other planes crossed the African coastline about 100 miles west of Oran and, moments later, five more C-47s appeared nearby. When he was unable to locate a landmark, Bentley landed and determined his position from some nearby Arabs. After one of his group’s planes had flown on alone, Bentley took off again. Two more C-47s joined up during the next flight.

Just after 8 a.m., Bentley spotted eight transports that had landed at the edge the Sebka d’Oran. He was told that Vichy snipers were shooting at the men on the ground and a column of vehicles was approaching. A radio discussion with Lt. Col. Raff led with the decision to drop paratroopers along a ridge dominating the approaches to the northern edge of the dry lake bed about 35 miles from Tafaraoui. Paratroopers jumped from at least nine C-47s.

While the other planes landed, Bentley continued an air reconnaissance. He saw smoke of battle around Tafaraoui and dodged antiaircraft fire before landing with engine trouble and raising Fredendall’s II Corps headquarters on the radio. While Bentley worked with the radio, one of the C-47s that had flown to Spanish Morocco landed nearby. The pilot had dropped his troops off to save gasoline and flown on toward Oran until he ran out of fuel. Minutes later, Vichy soldiers rolled up and took Bentley’s entire party prisoner.

Flying the third C-47 in the lead flight, Major Clarence Galligan may have been the first American pilot to land troops in enemy territory. He flew through antiaircraft fire along the coast and was attacked by a French fighter plane above the Sebka d’Oran. RAF Spitfires chased the French fighter away. Galligan landed his damaged plane on the dry lake bed about five miles from La Senia and walked with his crew and 14 paratroopers to its rim, where they dug in and waited. French fighters appeared overhead but did not strafe the group.

A company of French troops with a 75mm artillery piece in tow approached menacingly but did not attack, probably awaiting the arrival of Colonel Bentley, who was already a prisoner. Bentley advised Galligan to surrender, and the major complied.

By 9 a.m., 33 planes had reached the vicinity of Oran. Meanwhile, Raff had broken several ribs during the parachute jump and turned over command of his troopers to his executive officer, Major W.P. Yarborough. These men set out to identify the column that was advancing toward approximately 250 more paratroopers and troop carrier personnel who had taken cover from the sniper fire behind a low stone wall. The best news of the day so far was received when the approaching column was identified as American troops driving inland from Les Andalouses.

Once the snipers were driven away, an attempt was made to load the paratroopers who had been pinned down back aboard the planes and ferry them across the Sebka d’Oran to attack Tafaraoui. The effort was aborted when the landing gear of several planes became stuck in thick mud.

With the sun high in the sky, Yarborough ordered his men to rest, and while they ate lunch, he received a message that American ground troops advancing from the beachhead at Arzeu had captured Tafaraoui.

Yarborough sent a message back to the area where the C-47s were located, asking for volunteers to pick up three planeloads of paratroopers to garrison the Tafaraoui airfield. At 4 p.m., these planes reached Yarborough, and a few minutes later they were in the air with their cargoes of 2nd Battalion troopers. Five miles from Tafaraoui, six French fighters jumped the transports and forced them to land.

On the ground once again, Yarborough and his troopers continued on foot toward Tafaraoui and reached the airfield at sunrise the next morning. Trucks picked up wounded men and the crews of the three planes that had been left behind and delivered them to the airfield.

Around noon on November 8, word reached the transport crews and airborne troopers who remained at the edge of the Sebka d’Oran that Tafaraoui might be secure. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Schofield, commander of the 60th Troop Carrier Group and the ranking officer on the scene, dispatched Major John Oberdorf in a single C-47 to reconnoiter the airfield.

In less than an hour Oberdorf became the first American pilot to land at Tafaraoui. As his wheels touched down, French 75mm artillery peppered the field, and shrapnel clattered against his C-47. A few minutes later two more transports landed. When Schofield confirmed that the shooting had at least temporarily stopped, he allowed the remaining C-47s to load and fly to the airfield. As the afternoon wore on, 25 C-47s and two planeloads of paratroopers arrived Tafaraoui.

Four French Dewoitine fighters started strafing runs against the Americans at Tafaraoui, but Spitfires of the 31st Fighter Group, relocating to their new base from Gibraltar, shot them all down. Some aircraft and paratroopers were still scattered around North Africa by the time Oran fell on the morning of November 10.

As the first combat operation in the history of American airborne forces came to a close, casualties had been light, five dead and 15 wounded. Lieutenant Dave Kunkle, killed aboard one of the C-47s, was the first U.S. airborne officer to die in battle. Private John T. Mackall of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR, was wounded during a French fighter plane’s attack on his transport. Mackall died in a Gibraltar hospital on November 12, and Camp Hoffman, North Carolina, was renamed in his honor.

Most of the Americans who had missed their objectives were eventually reunited with the 509th, and the Vichy French released their prisoners. Those aboard the two C-47s that landed in French Morocco were detained until November 13 and performed some transport duty for the Western Task Force of Operation Torch before flying to Tafaraoui on November 20. The planes and paratroopers that landed in Spanish Morocco were interned until February 1943.

The first U.S. Army airborne combat mission had come to an anticlimactic end. Both the airfields at La Senia and Tafaraoui had been captured, and Oran was in American hands, but the airborne troops had played only a minor role in these successes. Several factors contributed to the generally disappointing results.

The entire mission amounted to an effort to take objectives within range of ground forces landing on the beaches near Oran. The 1,100-mile distance was too great for the transports to fly in formation, particularly with much of the journey in darkness. Communications were hampered by the failure of the beacons and the blunder that led the Alynbank to broadcast on the wrong frequency. Bad weather contributed to the loss of formation in flight as winds scattered C-47s over hundreds of miles.

Confusion regarding the response of the Vichy French also complicated matters, and the lack of information presented during the preflight briefings, including the totally erroneous information provided in one of them, was inexcusable.

Some observers have concluded that senior Allied commanders, including General Eisenhower, had authorized the deployment of the airborne troops with unnecessary haste. Air Marshal Welsh was probably not alone in his opinion that the goals of the mission did not outweigh the hazards that were encountered.

There were lessons to learn in the aftermath of that first mission, but in mid-November the Allies were racing with the Germans to occupy Tunisia. Airborne forces appeared to offer the best option to accelerate the effort to capture key positions.

On November 10, General Jimmy Doolittle, commanding the American Twelfth Air Force, ordered the 60th Troop Carrier Group to Maison Blanche, an airfield near Algiers, to join the 64th Group, which flew in on the 11th. About 300 paratroopers of the 509th PIR reached Maison Blanche aboard the 60th Group’s planes, while the transports of the 64th and the 62nd Groups supported the British 2 and 3 Parachute Battalions.

Lieutenant Colonel Raff and Major Martin E. Wanamaker, the senior officer of the 60th Group at Maison Blanche, were ordered to capture the crossroads town of Tebessa, where several routes into central Tunisia converged. Time was critical, but few good maps existed. Intelligence reports were sketchy, and due to the urgency of the situation planning was minimal.

While the troop carrier men performed maintenance and refueled, straining French gasoline to remove impurities, the paratroopers packed chutes and prepared for another combat jump. The best drop zone near Tebessa was identified as an old French airfield at Youks-les-Bains, 10 miles west of town.

At 7:30 a.m. on November 15, 20 planeloads of 2nd Battalion paratroopers took off from Maison Blanche for the 300-mile flight. Raff, in pain from his broken ribs, flew in the first transport, piloted by Wanamaker. Around 9:30 a.m., the paratroopers jumped from altitudes of 300- 400 feet.

Anxious moments occurred as the paratroopers came to earth. Trenches filled with combat troops and heavy weapons of the Vichy 3rd Zouave Regiment were directly below. Luckily, the Vichy soldiers were friendly. No shots were fired. Raff later commented that the “landing pattern over the target was perfect and well timed” and that the jump at Youks-les-Bains was the most successful of his career.

Raff sent a strong force forward to occupy Tebessa and soon determined that the way was open to Gabes on the Mediterranean coast. If the paratroopers were allowed to advance that distance, they might prevent the retreating Germans under Rommel from linking up with other enemy forces already in Tunisia. Raff radioed General Clark for permission to make the advance but was warned to go no further than Gafsa, 75 miles north of Tebessa.

Clark’s decision was correct. The paratroopers were lightly armed, and providing adequate support for them would have been problematic. Raff’s initiative did secure the right flank of the Allied advance toward Tunis through the critical month of February 1943.

On November 29, the British 2 Parachute Battalion jumped at Depienne to destroy German airfields and supply bases. German troops and tanks attacked them near the village of Oudna, and the British paratroopers fought a running battle across the desert, eventually covering a distance of 60 miles and losing half their number.

The last Allied airborne mission in North Africa took place on December 23, 1942, when 30 American paratroopers carrying 500 pounds of explosives dropped near El Djem to destroy a bridge. The planes flew low to avoid detection, and visibility was good with a full moon. The drop went flawlessly, but the troopers became disoriented and marched away from their objective rather than toward it. Most of them were captured by the Germans.

While the troop carrier groups remained active with logistical support, the Allied airborne units were utilized as infantry for extended periods during the remaining days of the North Africa Campaign. Senior commanders discussed additional parachute operations, but these proved unnecessary as Allied ground troops eventually trapped the Germans against the Mediterranean coast of Tunisia and forced one of the largest mass surrenders of World War II.

As the fighting in North Africa came to an end, the number of airborne troops based on the continent increased in preparation for their anticipated role in the next Allied offensive, the invasion of Sicily.

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History. He has written numerous books and articles on military history and resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments