By Eric Niderost

The young Oneida warrior paused, tensing as he spotted some activity in the forest just in front of him. His name was Paul Powless, and he was one of several Indian scouts sent out from Fort Stanwix in upstate New York. It was August 1777, and the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain had declared their independence the summer before, but the developing American Revolution showed no sign of ended soon. A mixed force of British regulars, American loyalists, German mercenaries, and British-allied Indians under Brig. Gen. Barrimore Matthew “Barry” St. Leger were on their way to capture the fort.

Powless could see the advancing figures clearly now, standing out in high relief against the more muted forest colors of brown and green. They were Indian warriors like him, muscular men who either sported shirts or displayed bare chests covered in tattoos and war paint. Their faces also were daubed in war paint, with red and black designs that boldly proclaimed the wearer’s personal taste. Powless noted they had shaved heads, much like him, save for a braid of hair called a scalp lock.

They were members of the alliance of six tribes that the French called the Iroquois League and the British called Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Oneida, Powless’ tribe, was one of the six, and although they were politically autonomous they were cultural and linguistic brethren. The approaching Iroquois were obviously going to fight for the British; as for the Oneida, they were on the Patriot side.

Seventeen-year-old Powless decided it was time to get back to the fort and report his findings. He was turning on his heel when he heard someone yell for him to stop. The young man halted, turned around, and saw a fair-skinned Indian warrior. The warrior assured Powless that he would not be harmed or detained. Powless stood his ground and motioned for the man to advance. But to protect himself in case the man was trying to deceive him, Powless raised his musket and told the warrior to stop a few feet away.

The young Oneida kept his musket trained on the warrior, his finger on the trigger, ready to shoot at the least sign of treachery. It was then that Powless realized who he had in his sights. It was Thayendanegea, whom the whites knew as Joseph Brant, the war chief of the Mohawks. Powless knew of Brant, for the chief was already a legend.

Brant was a gifted speaker, and he used all his powers to persuade the younger man to switch to the British side. He promised Powless great rewards if he did so. He also made veiled threats of dire consequences if Powless persisted in his steadfast loyalty to the Americans. Feigning sympathy, Brant expressed sorrow at the Oneida tribe’s impending ruin if it refused to switch sides.

Brant was a man of growing fame and prestige, but Powless was cowed neither by his physical presence nor by his slick tongue. Standing up straight and summoning all the confidence he could muster, Powless told Brant that the Oneidas would persevere, if need be, until such time as they were annihilated. The Oneidas had joined their fortunes with that of the American Patriots, and they would share with them whatever good or ill would come. Brant’s descriptions of the great and restless power of British King George III would not sway them.

There was nothing more to be said, but with the parley over, Powless knew his life was at risk. As a declared enemy, he might be killed and his scalp taken. The young warrior sprinted back to Fort Stanwix, the enemy Iroquois at his heels, but he finally managed to outdistance his pursuers and reach the safety of the stockade. Shots rang out; they were the first of many that would be heard in the coming days.

The siege of Fort Stanwix and the subsequent battle at Oriskany that unfolded on August 6, 1777, marked the beginning of the end of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, sometimes called the Great League of Peace and Power. The dates are disputed, but the confederacy likely was founded in the 15th century. Its main goal purpose was to stop the bloody tribal internecine warfare that had plagued the region for decades. Although the original alliance had religious overtones, by the 18th century it had developed political and diplomatic skills of great subtlety and effectiveness.

The lands of the Iroquois lay athwart the northern reaches of the New York Colony. These lands constituted a broad band of territory that stretched roughly from the Great Lakes to the Hudson River. It was an accident of history that their geographic location developed great strategic importance in the 17th and 18th centuries, for it was literally in the middle of the two great colonial rivals in eastern North America, which were France and Great Britain. The French were in Canada, north of Iroquois lands, while the British colonists were to the west and south.

There were five original tribes in the Confederacy, but they were joined by the Tuscaroras following the conclusion of the Tuscarora War in 1713. The Tuscarora had completed their migration north from the Carolinas and became the sixth tribe of the Iroquois League. The Iroquois collectively called themselves Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse). It was a reference to the common multifamily dwelling that could house as many as a dozen families and ranged from 50 feet to 150 feet in length.

To the Iroquois, their territory was a symbolic longhouse. The western door, or gateway, was guarded by the Seneca tribe, and the eastern door by the Mohawks. The Onondagas dwelled in the center, where they were keepers of the League’s Great Fire—literally and figuratively symbol of the League’s unity. The Cayugas, Tuscaroras, and Oneidas filled in the rest of the longhouse, with the latter having settlements near Oneida Lake.

The Iroquois had a system of government that was matriarchal, or close to it. An Iroquois traced his or her ancestry from the female line and was at birth a member of a female clan. Mature women wielded substantial power. The clan mother was a senior woman who, in consultation with other clan women, picked the tribal sachems. These sachems were special chiefs that formed a delegation to represent their tribe in the Great League Council at Onondaga.

The breakup of the Iroquois Confederacy can be traced to the elegant salons, watering spa, and gaming tables of Bath, England. That is where Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne was relaxing after military duty in America in the winter of 1776-1777. Burgoyne was a jack of all trades, but it remained to be seen if he was master of any of them. A man of fashion and an aristocrat who loved his champagne and women, Burgoyne also was a playwright and a Member of Parliament. London society knew him as “Gentleman Johnny” in tribute to his notorious penchant for high living and his mad passion for gambling.

Burgoyne conceived of a plan whereby he would crush the American Revolution in one glorious campaign. The idea was not new, but he dusted it off and made it his own. America was a wilderness with few roads, and the ones that did exist were scarcely more than primitive trails. That made lakes, rivers, and navigable streams essential for both trade and war.

His basic plan called for seizing control of the Hudson River in order to separate New England from the rest of the Thirteen Colonies. The British had long felt New England, particularly Massachusetts, was the heart of the rebellion. If the British controlled the Hudson corridor, New England would be cut off from the rest of the colonies. It was, for all intents and purposes, a matter of divide-and-conquer.

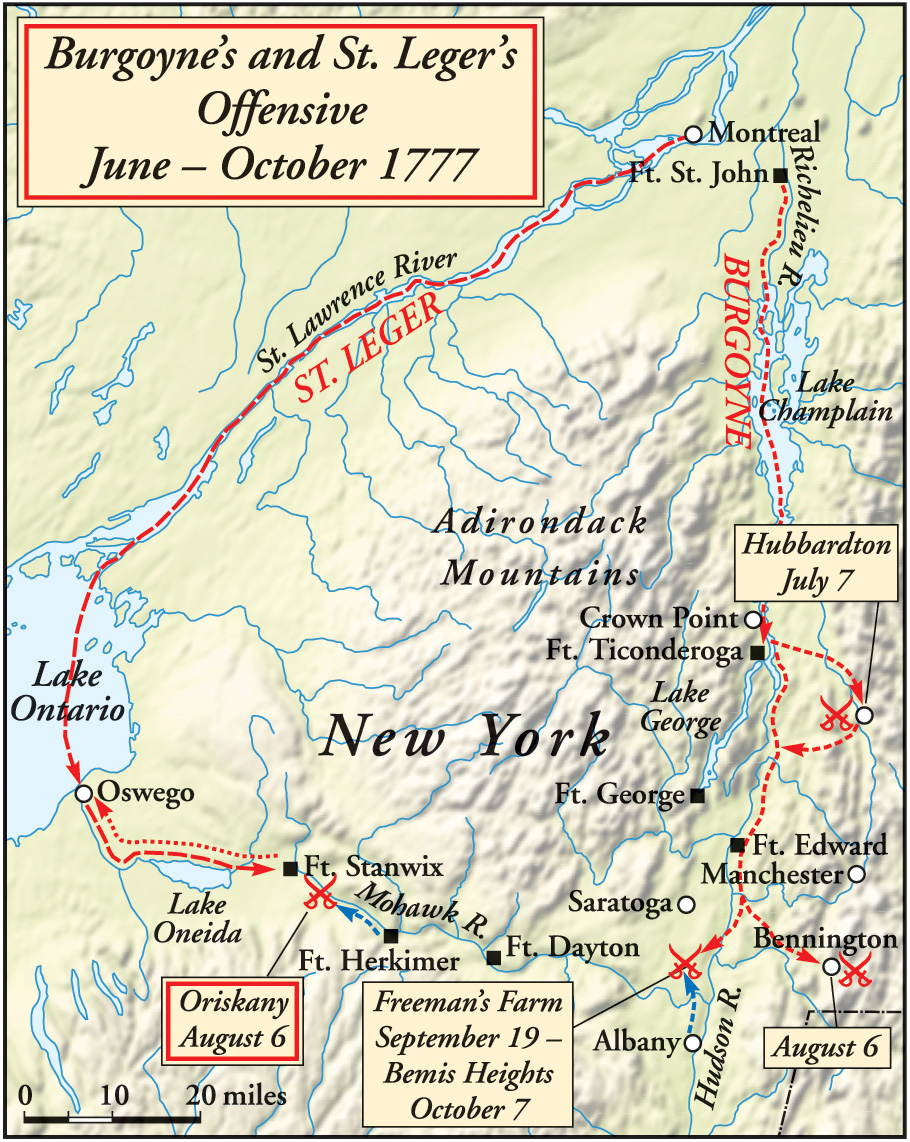

Burgoyne’s plan was approved, and preparations were put in motion at once. The campaign would consist of three separate elements, all converging on Albany in upstate New York. Burgoyne would lead an 8,000-man army down from Canada, going south from the St. Lawrence River. From there, the army would continue south down the Richelieu River to Lake Champlain and onward to the Hudson. The second element would be commanded by General William Howe, who was already in New York City with a large army. Howe would press north. By the time he met Burgoyne in Albany, the Hudson River would be under British control.

But there was a third element that is sometimes overlooked. St. Leger was to lead a mixed force of British regulars, American Loyalists (Tories), Canadians, German mercenaries, and Indians in this effort. The expedition would start at Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario and then proceed down the Oswego River, travel to the Seneca River, and eventually reach Oneida Lake. On the eastern end of the lake, boats could find Wood Creek, but after Wood Creek there was a dry-land portage of one to six miles (the distance depended on the season) called the Oneida Carry. Once past the carry, St. Leger’s army would travel down the Mohawk River to reach the Hudson.

St. Leger knew that success or failure of his expedition hinged on the active participation of the Iroquois. But his route was going to cross through the very heart of Oneida lands. In the weeks and months before the Burgoyne launched his campaign, the Oneida and other League tribes debated whether they should abandon their neutrality and raise the hatchet for the Great Father, King George III of England.

The Oneida had suffered substantial population losses because of war and disease, and they probably numbered no more than 1,600 people in the 18th century. That meant they could field about 300 warriors. Captives from other tribes, and even whites, were often adopted to replace dwindling numbers, and sometimes there was intermarriage as well. It was a common belief among Indians that a person’s heart and mind meant more than his birth origins or previous ethnicity.

The British government had declared a proclamation line in the 1760s. It was a western boundary that in theory protected Indian lands from white colonial encroachments. The line could be adjusted, and the Oneidas were not pleased when Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District, negotiated a line that took away some of their lands. There was insult to injury when Johnson took some of these lands as his own.

The Oneida received word in January 1777 that a terrible epidemic, in all likelihood smallpox, had decimated the Onondagas. Reports claimed that 90 were dead, including three important sachems. But the news was even worse than that: Because of the catastrophe, the Iroquois League Grand Council fire had been extinguished and would not be rekindled anytime soon. The fire was highly symbolic, the guiding light of unity and the beacon of consensus within the Six Nations. The implication of the extinguished fire was that, both in theory and in fact, each of the member tribes would follow its own destiny.

St. Leger was at Oswego in July of that year making the final preparations for his campaign. Brant also was on hand, his chief function at the moment to try and persuade as many Iroquois as he could to join the expedition. Brant’s silver-tongued oratory was supplemented by a shipload of British gifts, including ostrich feathers, small jiggling bells, gun barrels, and kegs of rum. A large number of Iroquois warriors decided to join up, but not all were convinced. There were some Senecas who, while agreeing to go along, insisted they would be there strictly as observers, to watch their brothers whip the rebels.

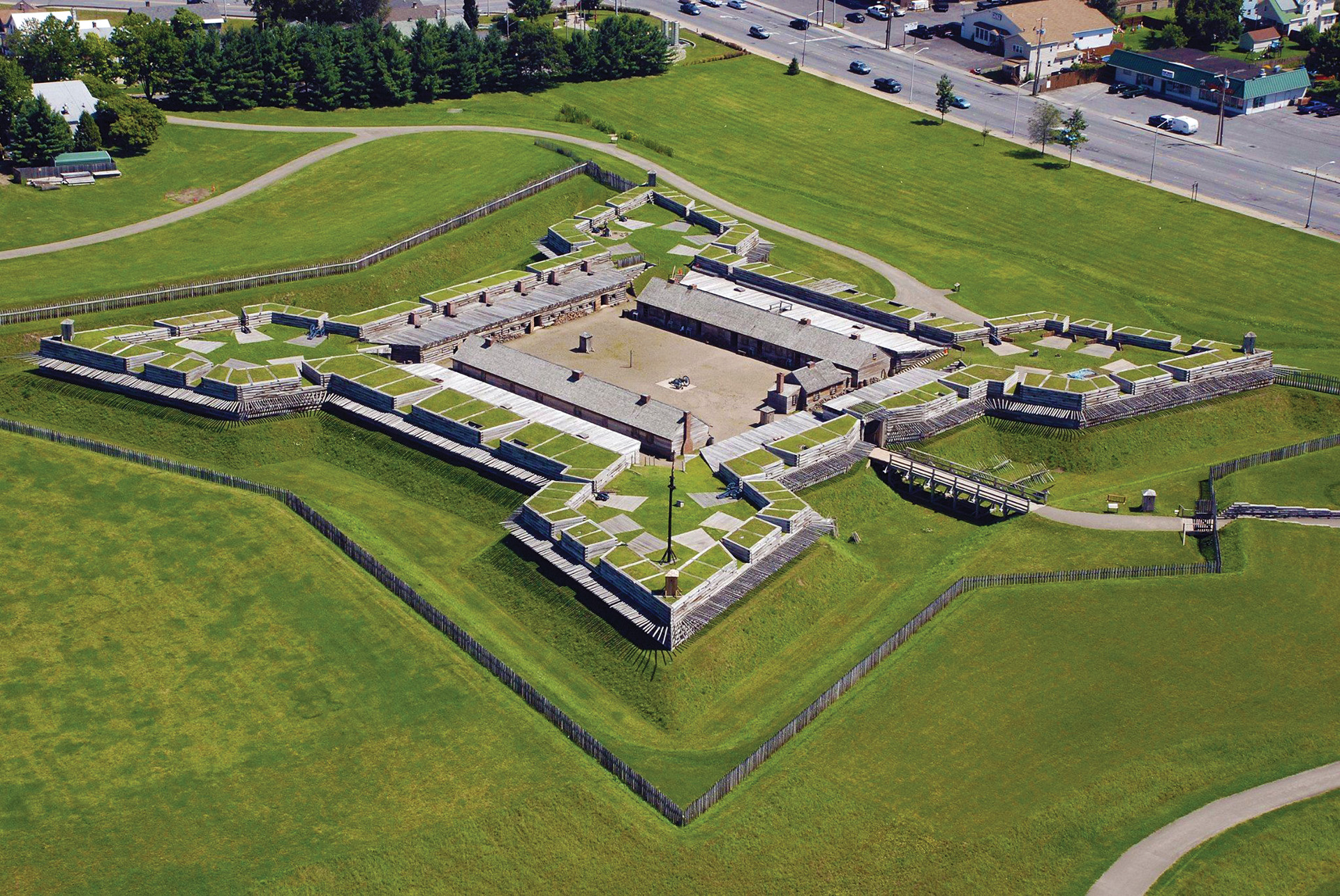

The one major obstacle in St. Leger’s journey to Albany was Fort Stanwix, which guarded the Oneida Carry portage. Built in 1758 during the French and Indian War, Fort Stanwix was allowed to fall into decay following the conflict. When the Americans reoccupied it in 1776, it was in a seriously dilapidated state. Fortunately for the Patriots, the Oneidas were firmly on their side. They had urged the Americans to prepare the fort so that “nothing might pass and repass to the hurt of our country.”

The Americans heeded the warning, and every effort was made to repair and strengthen the fort. Stanwix was a typical fort that incorporated the basic ideas of the great seventeenth-century engineer Vauban. It was made of timber, the material most readily available in a forested country, with a starburst pattern of four pentagonal bastions projecting from each corner of the square curtain walls. The fort was also surrounded by a grassy embankment known as a glacis, a deep ditch, and a parapet wall of six-foot high wooden stakes.

The fort’s builders had topped the ramparts with parapets, and the boundaries between them were marked by a line of fraise, sharpened wooden stakes that jutted out horizontally. Among other things, fraise made the use of scaling ladders problematic at best. The defenders had placed embrasures on the parapets at fixed intervals. These gaps allowed the black snouts of artillery pieces to poke through. Their fire would have a deadly effect on any attacking force.

Fort Stanwix’s artillery consisted of three 9-pounders, four 6-pounders, two 3-pounders, and four Royal mortars. The name of each gun referred to the weight of the solid shot it fired. The 9-pounders had an effective range of one mile. The garrison was composed of 500 Continentals from the Third New York and Ninth Massachusetts regiments. The morale of the troops was high, in no small part because they were led by Colonel Peter Gansevoort, who was popular with his men.

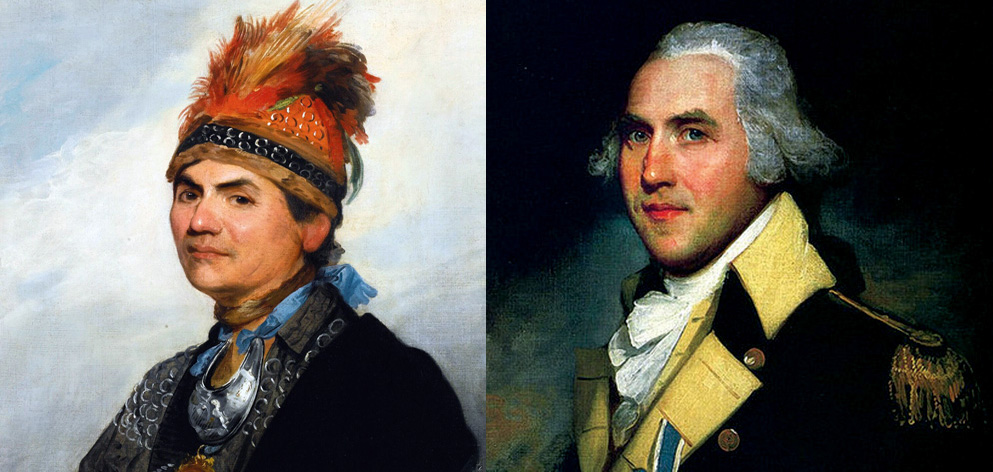

Gansevoort, who was just 28 years old, hailed from a prominent Albany family of Dutch origin. The young officer had seen some active service in 1775 but was inexperienced as an independent commander. Yet Gansevoort was resourceful and utterly fearless. With these qualities, he was not going to be intimidated by British threats.

St. Leger departed Oswego on July 26, 1777. His force had a core of professional soldiers that included 100 infantry of the 34th Foot, 100 of the 8th Foot, and 80 Hessian mercenaries from Hesse-Hanau. In addition, there were 380 men of the King’s Royal Regiment (Loyalists) of New York, 70 Loyalist rangers, 50 Canadians, and 700 Iroquois warriors.

The British brigadier general’s own arrogance and overconfidence was going to play a major role in the coming campaign. Initial intelligence described Fort Stanwix as out of repair, a dilapidated ruin. These reports had been true, but they were now out of date. St. Leger did receive updated information, but for some reason he chose to ignore it. Because of this lapse of judgement, his artillery train was woefully inadequate for the task at hand.

The British expedition set off in good spirits, and made good progress in their travels, with advance elements arriving at Fort Stanwix on August 2. St. Leger was surprised to discover Fort Stanwix was far from the ruin he’d expected to see. Some of the reconstruction had not yet been completed, but the fort was still a very formidable obstacle to British plans.

St. Leger sent Captain Gilbert Tice under a flag of truce to demand an immediate surrender. If the rebel garrison proved obstinate, Tice was to look around the fort and bring back what intelligence as he could. Unfortunately, British hopes of gleaning intelligence from Tice were dashed because the Patriots blindfolded him before he entered the fort, and he was forbidden from removing the blindfold until he was inside one of the fort’s buildings.

Gansevoort rejected any notion of capitulation, so St. Leger was forced to prepare for an extended siege. To test the mettle of the defenders, Hessian Jagers began to snipe at anyone who exposed himself even for a moment. The Jagers were armed with rifles, which were far more accurate than the standard smoothbore muskets of the day.

Approximately 200 Senecas came to join the British the following day. They were accompanied by an unspecified number of additional warriors from the Wyandot, Ottowa, Potawatomi and Chippewa tribes from the Detroit region. They broke up into small groups, placed themselves around the fort, and then began a constant and steady fire on the defenders. Some of the natives had rifles, others muskets, but all copied the Jagers to the best of their ability in maintaining sniper fire that killed one defender and wounded several others.

The Indians supplemented their harassing fire with loud war whoops, fearsome ululations that often lasted through the night. The war whoops sent shivers of fear down the spines of the uninitiated but also deprived the more experienced of much-needed sleep. In the meantime, St. Leger had to solve some logistical problems. Just before the British arrived, the Americans had purposely felled trees and dumped them into Wood Creek. The result was log jams that either blocked the waterway or at the very least created major hazards to navigation.

Since vital supplies and the artillery train were coming by water, this problem demanded immediate attention. The Loyalists and Canadians were assigned the arduous task of clearing the creek, while Colonel Sir John Johnson’s King’s Royal Regiment was tasked with building a road that would bypass the stream altogether.

The Fort Stanwix garrison might have been confident, but it was obvious the siege would not be broken until they received help from a relief force. An Oneida woman, Tyonajanegen (Two Kettles Together), the wife of Oneida chief Hanyery, slipped out of the fort and successfully stole through British lines to spread word of the ongoing siege. She stopped at Oriska, her home village, before proceeding on to Fort Dayton.

Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler of the Continental Army was the ranking officer in the region. As head of the Northern Department, he had his hands full with the developing invasion under Burgoyne. He could spare no regular troops to confront St. Leger, so the best option was to call out the local militia. Brig. Gen. Nicholas Herkimer issued an order for the Tryon County Militia to gather at Fort Dayton for the relief of Stanwix, 28 miles to the west.

in 1779 against the pro-British tribes of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy earned

the gratitude of the Continental Congress.

Herkimer was a prosperous and well-liked landowner of German stock. This was not unusual, for most of his neighbors either hailed from the Palatine region of Germany or were first-generation German American. Herkimer was born in America but spoke English with a thick German accent. When the militiamen turned out, they probably used German when conversing among themselves.

The Tryon County Militia was formed into a brigade of four regiments. The First Regiment (Canajoharie) was under Colonel Ebenezer Cox, the Second (Palatine) Regiment under Colonel Jacob Klock, the Third (Mohawk) Regiment under Colonel Frederick Visscher, and the Fourth (Kingsland/German Flats) Regiment under Colonel Peter Bellinger.

Many militiamen were reluctant to leave their homes and families, as hostile pro-British Indians had been frequently staging bloody raids. Terrible stories fueled the fear. Before the siege, two young girls had been killed and scalped while picking berries near the Fort Stanwix. Nevertheless, 800 members of the Tyron County militia assembled at Fort Dayton as ordered.

The militia started its march on August 4, marching west along the Mohawk River. The following evening, they reached the Oneida village of Oriska, from which the place name Oriskany is derived. At Oriska they were joined by 60 Oneida warriors led by chiefs Cornelius and Hanyery Tewahangarahken. Although relatively few in number, they were going to be invaluable allies in the coming days.

Chief Hanyery, who was in his 50s, was a respected member of the Oneidas. Although he was getting too old for combat, he had a reputation for going fearlessly into battle. His wife, Two Kettles Together, who was the same woman who brought word of the Fort Stanwix siege, accompanied him on the warpath, as did his grown son Cornelius Doxtader. Chief Hanyery was on horseback and wore a sword—not tomahawk—as a symbol of his importance.

The Herkimer relief column, comprising 800 men and 15 baggage wagons, was too large a body of men to go undetected for very long. Molly Brant, as fiercely pro-British as her brother Joseph, relayed intelligence to St. Leger that Herkimer was coming and was due to arrive at Fort Stanwix shortly.

The British general received this news with some consternation; most of the men were busily engaged in clearing Wood Creek and constructing the military access road, and they could not be spared. As a makeshift measure, St. Leger decided to dispatch 80 men, some of whom were rangers, as well as the whole of the Indian corps. The Indian contingent included Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk, as well as handfuls of warriors from other, non-Iroquois tribes.

In consultation with other officers, St. Leger decided the best option was to ambush the Herkimer column as they marched towards the fort. Tory Major John Butler, who would later become the infamous leader of Butler’s Rangers, had a hand in the planning, as did Seneca chief Cornplanter and Sir John Johnson.

After some debate, a section of the Albany-Oswego road was selected for the ambush. It was an area where the ground rose into a plateau that overlooked the Mohawk River, but the road itself dipped down to follow a ravine that was about thirty feet lower than the higher terrain. A small stream wandered into the ravine, bisecting the road and making the ravine bottom a swampy, viscous muck. A corduroy road made of felled trees should have helped, but it was apparently in disrepair. A thick forest of hemlock, beech, birch, and maple crowded all around, making prefect cover for any ambushers.

When Herkimer’s relief column camped at Oriska, they were only about eight miles from Fort Stanwix. Herkimer sent three scouts ahead to the fort to let Gansevoort know that they were in the vicinity and would arrive soon. The relayed message told Colonel Gansevoort to fire three cannons as a signal that the scouts had arrived safely and that the militia should advance. Herkimer also asked Fort Stanwix to stage a kind of diversionary attack.

The morning of August 6 dawned warm, promising that a hot day lay ahead. But tempers as well as temperatures were soon rising. Herkimer was in no real rush to get underway because he wanted to hear the signal cannons from Fort Stanwix first. During an officer’s call that morning, most of his subordinates were eager to move on. When Herkimer showed reluctance to leave, he was accused of cowardice and having Loyalist sympathies. After all, his own brother was a notable loyalist.

Stung by these accusations, Herkimer ordered an immediate advance on Fort Stanwix. He placed himself at the head of an advance guard and then formed a column of the First, Second, and Fourth Militia Regiments. The wagons were next in line, followed by the Third Regiment as a rear guard. The sixty Oneida warriors were apparently marching in clusters, a few with each militia regiment and the wagon train. The issue is disputed, but apparently Herkimer did not make any attempt to use the Oneida, who were expert scouts and woodsmen, as flankers. It would prove to be a near-fatal error.

The British ambush was simple and effective, making full use of the ravine and the forested areas around it. The forest also had underbrush, ideal for concealment and enabling large numbers of Brant’s men on both sides of the road to escape detection. When virtually the entire relief column was within the ambush zone, the signal would be given for the trap to be sprung. Brant’s warriors were positioned to cut off any escape from the rear.

It was 10:00 am on August 6 when Herkimer and the Tryon County Militia entered the ambush zone. All seemed peaceful, with rays of sunlight filtering through the trees to form dappled patterns on the ground. The only noise was the shuffling sound of men walking, the jingle of harnesses, and the creaking groans of axles as the wagons negotiated the boggy ravine.

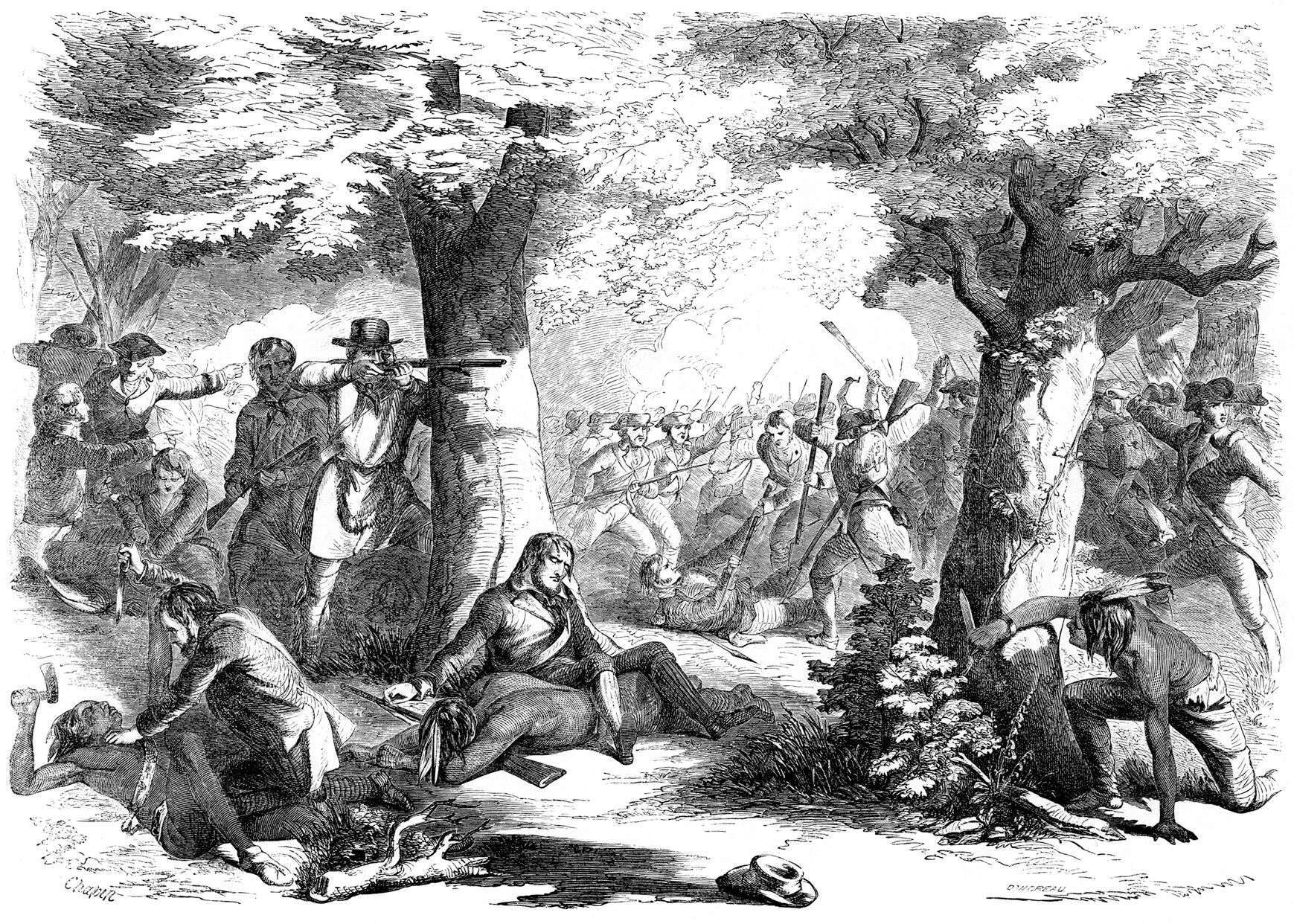

Herkimer passed through the ravine and was guiding his horse to higher ground when he heard popping sounds—the unmistakable sounds of rifles and muskets being discharged. Some of the pro-British Indians, impatient and eager to engage the enemy, had started a premature attack. Most of the rear guard and wagon train had not yet entered the trap, but unnerved by the surprise, their resistance was brief. Most took to their heels, followed by Brant’s Mohawk warriors armed with guns, hatchets, and knives. Fleeing militiamen were dispatched without mercy, until their dead and scalped bodies formed a bloodied detritus that stretched for miles.

Herkimer tried to rally his men, but as he approached Colonel Klock’s 2nd Regiment a musket ball hit his horse, going through the animal and shattering Herkimer’s leg. The horse fell and pinned the general to the ground, but some militiamen managed to drag him out. The men carried him to a nearby beech tree, where he propped himself up and continued to guide his troops as best he could.

The battle became a confused and bloody melee with no rhyme and less reason to the terrified militiamen. Gouts of white smoke erupted from muskets, marking where assailants were firing, but it was hard to find a target when the enemy hid behind massive tree trunks or leafy branches and undergrowth. The Indians fighting for St. Leger sometimes waited until the militia fired a volley, and then rushed in with knives or hatchets before the militiamen could reload.

The Oneida warriors distinguished themselves in this battle, fully living up to their Iroquois heritage. Chief Hanyery was in the thick of the fight, with Two Kettles Together standing by his side, sharing the danger as she loaded and reloaded his musket. When a bullet smashed his wrist and he was unable to effectively use his gun, he wielded a tomahawk with his other hand. Two Kettles Together also fought, using a pistol with good effect. Their son, whose name was Philip, also was credited with killing two enemy warriors.

In the midst of the melee, Louis Atayataronghta noticed one Indian on the British side who seemed to be something of a sniper. “Every time he rises up, he kills one of our men,” Atayataronghhta said to another member of the militia. “Either he or I must die.” Atayataronghhta then waited patiently until the sniper raised his head, then drew a bead and squeezed the trigger. The Indian was hit, and his lifeless body sprawled over a tree limb. Atayataronghhta, who was a Mohawk but fighting on the Patriot side, let out a war whoop, sprinted over to the body, and took his scalp.

After about three hours of intense fighting, rain clouds darkened the skies, and before long friend and foe alike were soaked by a drenching rain. It seemed as if the very floodgates of heaven had opened up, but the deluge was a blessing because the fighting stopped, giving the Americans time to reorganize and regroup. Herkimer, badly wounded but still alert and very much in command, organized defensive circles and saw to it that the men fought in pairs. That way one could reload while his partner held off any attackers with his own musket.

The battle resumed, this time with the loyalist New York King’s Royal Regiment attempting a ruse. Johnson knew that the battered militia survivors were hoping for help from Fort Stanwix, so he told his men to turn their green jackets inside out to pretend they were Americans. Militia Captain Gardiner saw through the trick and warned his men. The captain was bayoneted by a loyalist soldier, but the militia now heeded his warning, and the subterfuge failed.

Herkimer lost about half his command, and the survivors were bloodied and exhausted. The surviving militia and their Oneida allies were holding their own, but the stalemate could not last forever, and the odds seemed stacked against them. But the high-pitched and piercing war whoops from Brant’s warriors were soon replaced by shouts of “Onenh! Onenh!” which was the signal for departure or withdrawal.

The pro-British Indians started to disengage and fall back as the cries to withdraw grew louder over the din of battle. Word apparently had gotten out that something was amiss at Fort Stanwix, and the Indians pulled out to investigate. Without native support, the Hessians and Loyalist troops had no choice but to follow suit.

The Indian retreat was justified, because Gansevoort had staged a major sortie at Fort Stanwix against a nearly empty British and Indian camp. Lt. Col. Marinius Willett, Gansevoort’s second-in-command, was in charge of the operation, which totaled 250 men. The raiders quickly killed the few guards that were stationed in the camp, at the same time scaring off the Indian women, who fled to the woods. Two more Indians soon died of camp sickness and four were taken prisoner.

The sortie took “fifty brass kettles, and more than one hundred blankets … with a number of muskets, tomahawks, spears, ammunition, clothing, deerskins, a variety of Indian affairs, and five colors,” wrote Willetts, who was proud of the accomplishment. Even better, confidential British papers were discovered, including letters to St. Leger and Johnson’s orderly book.

When Brant and his warriors returned to their plundered camp, they were angered and outraged. There wasn’t much that the raiders had overlooked, and clothes, weapons, and blankets were going to be keenly missed. Many of the warriors had stripped to just a breechcloth for battle, and now they found that was the only thing, except for some weapons, that they possessed.

In terms of the numbers engaged, Oriskany was one of the bloodiest battles of the American Revolution. The militia had started the day with 800 effectives, but as evening fell only 150 walked away, taking with them about 50 wounded. The rest were dead. At least 200 had died in battle, and possibly many more. Scores had been taken prisoner, but the pro-British Iroquois were so enraged at their own losses that the lives of these captives were forfeit.

There was little alternative but for Herkimer to retreat back to Fort Dayton. The Tryon Militia had been effectively destroyed, but events were to prove that they had achieved a kind of victory, even if it was a pyrrhic one. The heavy losses that the Brant Indians had sustained made them sullen and resentful, and certainly less enthusiastic about the British cause. Returning to a plundered camp did not lighten their mood.

Brant’s warriors also had suffered heavy casualties. As many as three dozen Senecas had been killed, including six chiefs. That figure does not include the British-allied warriors from other tribes, or the Mohawks. The Hessians and Loyalists suffered lightly, losing just 25 killed. St. Leger, knowing that much depended on their continued presence, decided to use the Indians’ growing anger as a bargaining chip.

St. Leger penned a message on August 8 to Gansevoort under a flag of truce. The missive demanded surrender but added an ominous postscript: the Indians were seething with anger at their Oriskany losses and were eager to take revenge. If the garrison did not surrender, every man, woman, and child would be slaughtered without mercy. And that was not the end of it, for the Brant warriors wanted to raid the American settlement at German Flats. Once there, they intended to kill everyone they found regardless of his or her age or sex.

It was the Americans’ worst nightmare, but Gansevoort would not yield to bullying or threats. “It is my determined resolution with the forces under my command to defend this fort and garrison to the last extremity,” he said.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, who had not yet become a traitor to the Patriot cause, assembled another relief column. Rumors were deliberately spread that exaggerated the size of his forces, hearsay that got back to the Indians at the Fort Stanwix siege. It was the last straw: Brant’s native warriors started leaving in droves. St. Leger soon had virtually no Indians under his command. There was little the colonel could do to stop the manpower hemorrhage, and he believed the Arnold rumor as well. The British general reluctantly lifted the siege and withdrew to Canada.

By that time Burgoyne’s three-pronged offensive was in shambles. The Americans soundly defeated his army at Saratoga in October 1777. The major victory brought France into the war on the American side. The campaign of Saratoga stood as a major event in the birth of the United States, but it could be said that the birth of one nation occasioned the destruction of another. The Iroquois League was permanently broken, never to rise again, although the individual tribes survived and ultimately prospered into the 21st century.