By Christopher Miskimon

U.S. Army Sergeant Vere Williams listened to his instincts as his landing craft approached the beach. It was August 15, 1944, and his unit, the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Division was part of the invasion force for Operation Dragoon, the landings along France’s Mediterranean coast. Williams, a farm boy from the tiny community of Snyder, Colorado, carried the nickname “Tarzan” due to his good looks and strong, broad chest. He joined the 157th in 1938 for the extra four dollars a month it provided his family. His regiment was on its fourth amphibious assault of the war, and most of the men he started with were either dead or wounded. Despite only being in his twenties, Tarzan Williams was an old-timer, for life as a combat infantryman quickly gave survivors a morbid seniority.

Opposition was light that day. All the subsequent histories would say so. Still, Williams’ nagging inner voice told him something was wrong. His Higgins boat was in the second wave so there were already many troops ashore. The ramp at the front of the landing craft dropped and the men inside quickly moved out. The young sergeant rushed to a nearby hillside to join his company. Mortar rounds began to land nearby and soon came closer. One landed 15 feet away, and Williams felt something hit his leg. He looked at it but saw nothing. He then noticed two other men near him were hit, one in the face and the other in the hand. He checked his leg again and found a hole in his pants and blood running down his knee.

A medic arrived to help them, but Williams’ inner voice told him they needed to move. His gut said the Germans were zeroing in on them. He told the others and they dashed behind a nearby boulder. Seconds later another mortar bomb landed exactly where they had been sitting. The medic finished his first aid and Williams was evacuated. He was one of only seven casualties in the 157th that day, but the distinction meant little. At least that nagging premonition had saved his life and those of the others. He soon wound up at a hospital in Naples for two weeks, while his parents got a telegram erroneously stating he was missing in action. By the time the Army corrected its mistake a month later, Williams was back in action in France.

By mid-1944 the war had turned decisively in the Allies’ favor, but it was far from over. The Third Reich still occupied most of France. In Normandy the Anglo-American forces were pushing out of the hedgerows and fields, but German opposition was still stiff and unrelenting. The supply situation was also difficult due to German sabotage of the port of Cherbourg and a storm that wrecked one of the artificial harbors painstakingly built at the Normandy landing beaches. More ports were needed and the Nazis needed to be further distracted.

A solution to both problems was quickly pulled from the Allied backburner. Operation Anvil was a plan to land troops on the coast of southern France that would threaten the occupying German Army from its rear. The idea was placed on hold due to both a shortage of landing craft and the drain on resources by the continuing stalemate at Anzio. By July 1944 the success at Normandy and the Anzio breakout relieved these problems. So the Americans revisited their plans for an invasion of southern France.

The plan offered several advantages. If successful it would bring the ports of Marseille and Toulon under Allied control. Additionally, the Germans would have to defend two fronts in France. While the Russians liked the idea as a supporting effort to Normandy, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill disliked it. He knew it would take attention away from the Italian campaign, a cherished project as it might lead to an advance into the Balkans, something Churchill was fixated on. Determined to stop the operation, Churchill made a plea to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to abandon it, but U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall advised proceeding and Roosevelt agreed. The plan was reactivated on July 14 with the new codename Dragoon. The name of the operation reportedly was offered by Churchill, who felt he had been dragooned into accepting the amphibious operation.

The Free French Forces under General Charles de Gaulle also favored Dragoon as a way to get more of their troops fighting in France. By this point in the war the French were finally assembling a sizable army and did not want it wasted in the attritional struggle in Italy. Given the newly available transports and landing vessels, French divisions could quickly be transferred from Italy to the southern French coast. The stubborn and often difficult de Gaulle demanded his forces be redeployed as part of the Dragoon landings. The final plan combined French troops with an American landing force and an Anglo-American airborne contingent.

The American contribution included three veteran infantry divisions from the Italian campaign. They were organized as the VI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, which was part of General Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army. The 3rd Infantry Division, nicknamed the “Rock of the Marne,” was a regular Army formation with experience in North Africa, Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio. The 36th Infantry Division was a Texas National Guard unit sometimes called the Lone Star Division. It entered the war at Salerno the previous autumn and suffered heavy casualties during the fighting along the Rapido River in January 1944, but after rebuilding it went into action again at Anzio where it performed well during the advance to Rome. The 45th Infantry Division, nicknamed the Thunderbird Division, was composed of National Guard formations from Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. It saw action in a variety of settings, including Sicily, Salerno, along the Volturno River, and Anzio. Operation Dragoon would be its fourth amphibious assault of the war.

Each division had three infantry regiments formed into regimental combat teams, which included a dedicated artillery battalion and the added combat power of attached tank, engineer, and tank destroyer units. At this point in the war these combined units had generally worked with each other for some time and were smoothly functioning entities. All were well suited to the task at hand and formed the assault force for the amphibious attack.

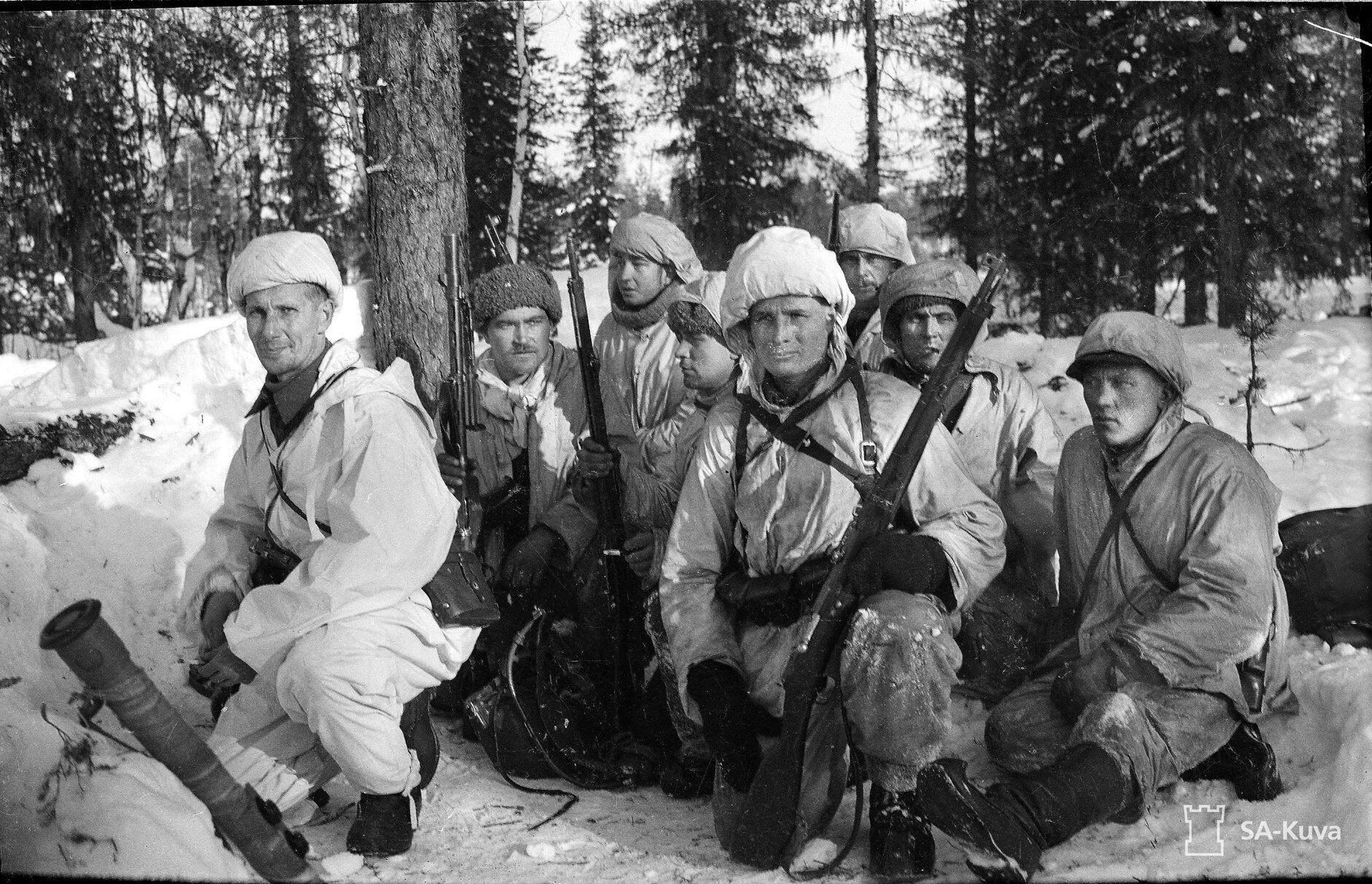

There was no airborne division available in the Mediterranean region, but the Allies had used paratroopers successfully enough at Normandy to warrant their use in Dragoon. The 1st Airborne Task Force was an ad-hoc combination of the few available parachute-qualified troops and several regular units hastily given glider training. Essentially a small division, it was led by Brig. Gen. Robert Frederick, the famous leader of the Canadian-American 1st Special Service Force, known as the Devil’s Brigade. The remnants of that unit were available in theater and combined with the only large British ground force used in the operation, three battalions of the 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade. A number of artillery and support units were trained in glider operations, including the Antitank Company of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the Japanese-American unit that fought with great distinction during the war.

Likewise, the Allies had no large American armored formations available for Dragoon either, so again they created one. The original plan was to use one combat command from a French armored division but that idea was soon dismissed. Still, a mobile force would be valuable to exploit any gaps or weaknesses in the German defense so the assistant commander of VI Corps, Brig. Gen. Fred Butler, was appointed to command the scratch force, which was built around the 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron (Mechanized). This unit was reinforced with truck-borne infantry along with tank and tank destroyer units, an artillery battalion, and a company of engineers. Although it was a small force, it was quite powerful.

The French contingent included the II Army Corps commanded by General Edgard de Larminat, part of the French Army B under General Jean de Lattre. He had one armored and three infantry divisions. Two of the infantry units had good reputations from fighting in Italy. There were also a number of French Special Forces units and thousands of French Resistance fighters throughout the countryside.

To support the assault the Western Naval Task Force was reinforced with ships no longer needed at Normandy. American, British, and Free French vessels were combined into several task forces with five battleships, nine escort carriers, 22 cruisers, 85 destroyers and hundreds of smaller warships, transports, and cargo ships. Additionally, there were 1,267 landing craft of various types. One task force formed the command group while three others were assigned one to each landing beach. The carriers were grouped into their own task force while a sixth task force supported the special operations forces, which would secure various islands.

The Allies also could depend on extensive air forces for Dragoon. The Mediterranean Allied Air Force had to support operations across the theater, and it detailed a specific number of tactical aircraft to support the landings. The XII Tactical Air Command received orders to support the landings. In response, the XII TAC sent 216 Hellcats, Wildcats, and Spitfires to operate from the carriers.

The Allies not only had carriers stationed to support the landing, but also aircraft based on Corsica that were within range of the coast of Provence. The Corsican airfields housed 12 squadrons of B-25s and four squadrons of A-20s. Fighter squadrons included 15 squadrons of P-47s and six squadrons of P-38s. The British moved 11 Spitfire squadrons and one Beau night fighter squadron to Corsica. In addition, the French had four P-47 squadrons and some Spitfires. Also stationed on Corsica were three reconnaissance squadrons. Altogether, the Allies had 2,100 aircraft on Corsica.

The German defenders were organized under Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz’s Army Group G, which had been stripped of most of its best divisions for the fighting in Anzio and later Normandy. General der Infanterie Friedrich Wiese’s Armeeoberkommando (AOK) 19 was a subunit positioned in the path of Dragoon. By August 1944 it had two corps: the 62 Korps with the 242 Infanterie-Division (static) and 148 Reserve-Infanterie Division, while 85 Korps had two static infantry divisions numbered 244 and 338. Static divisions were meant to man prepared fortifications and lacked wheeled vehicles to move their troops. To make up for this shortcoming they were often given extra machine guns and artillery. Another division, the 157 Reserve-Infanterie, was stationed away from the coast where it was engaged against partisans.

Army Group G’s main reserve was Generalleutnant Wend von Wietersheim’s understrength 11th Panzer Division. The Germans had pulled the division out of the Eastern Front in June 1944 and sent it to Bourdeaux for refitting where the 1st Battalion of the 15th Panzer Regiment received Panther tanks while its 2nd Battalion remained equipped with long-barreled Panzer IVs. In July, Wietersheim received orders to redeploy to Toulouse. Assisting the German frontline forces were various German security troops scattered throughout the region.

Although the German forces were well organized, some of their units went into battle with inferior equipment and second-rate troops. Moreover, they had to man defenses that were in many cases unfinished. For example, the unit directly in the Allied path, the 242 Infanterie-Division, was assigned more than 90 miles of coastline with its 12,000 troops.

Of its 12 infantry battalions, three were Ost troops from Armenia and Azerbaijan. These troops were armed with captured mortars, artillery, and antitank guns from France and Italy. Since there was no transport to provide resupply, each unit had about six day’s of ammunition on hand but no way to transport it if the unit had to move or retreat. The only mobile troops were a company equipped with bicycles in each battalion.

The Germans had established and occupied a number of defensive positions, including some old French fortifications. Although they were actively strengthening both new and old defenses, the upgrades were far from completion. Only 892 of a planned 1,544 bunkers and casemates were finished before the invasion. As for the beach obstacles, less than one-third were completed. The Germans had placed few mines on the beaches, although there were many inland minefields. Kriegsmarine forces consisted of small coastal warships and one submarine. The Luftwaffe was severely depleted by earlier fighting. For that reason, there were only 83 fighters and light bombers available.

The invasion began in the predawn hours of August 15 with a deception operation. A task group of small Allied warships deployed to both flanks of the actual landing area and simulated landings to draw away and confuse the defenders. The warships used radar deflectors and towed balloons to simulate a larger force. To further confuse the enemy, the Allies dropped dummy paratroopers on the mainland.

The 1st Special Services Force targeted the islands of Port-Cros and Levant located just south of the landing beaches. The group attacking Levant landed with no opposition; however, the guns on the island were fake and the defenders poorly protected in old French forts and monasteries. By the end of the day, the Allies had cleared the island.

As for Port-Cros, the Americans landed without difficulty and soon had the Germans bottled up in an old fort. Yet the Germans managed to hold out for two days against infantry and a steady pounding from aircraft and naval gunfire. But when a British battleship armed with 15-inch guns began to shell it, the Germans promptly surrendered.

While the Americans seized the islands close offshore, the French commandos of Romeo Force landed near Cavaliere to disable a number of coastal guns. An advance force of 60 commandos found they were too far east of the gun emplacement at Cap Negre, so they quickly marched there and captured it. The main body of the unit landed soon after and set up roadblocks. A second mission named Rosie Force was less fortunate. Sent to Deux Freres Pointe, the American scout troops entered a minefield where they became pinned down by enemy fire. They had little choice but to surrender the following day.

As the commando units clashed on the island and beaches, 400 aircraft roared overhead in the predawn light transporting 5,600 paratroopers and 150 artillery pieces to inland targets. Only two of the nine pathfinder teams sent ahead of the main body landed near their designated drop zones. The radios proved ineffective and fog covered most of the area, forcing the pilots to do their best. Some of the pilots associated hilltops poking through the low fog to points on their maps to locate drop zones, but they still had difficulty navigating. The formations, known as serials, typically flew in groupings of 26, 45, or 54. One serial dropped 600 troops 10 miles from its intended zone. The paratroopers came down near the town of Saint-Tropez. Even those who landed near their targets had trouble collecting their equipment and artillery due to the fog and hilly terrain. Only 40 percent of the American airborne troops landed within a mile of their objectives.

The British parachutists had a better time with about 60 percent of their troops landing near the drop zone, mainly due to Eureka beacons set up by their pathfinders. Glider-borne reinforcements came soon after, carrying the English artillery. British and American glider missions continued throughout the day with the later missions achieving better results due to clearer weather.

The last glider missions, which landed at 6 pm, were the most accurate. By then, 9,000 troops, 213 guns, and 221 vehicles were delivered. Despite the drop zone problems the Airborne Task Force was a success. It established itself around Le Muy and upset German defenses throughout the area. The rear-echelon defenders consisted of police units, headquarters components, and a horse-drawn transport battalion.

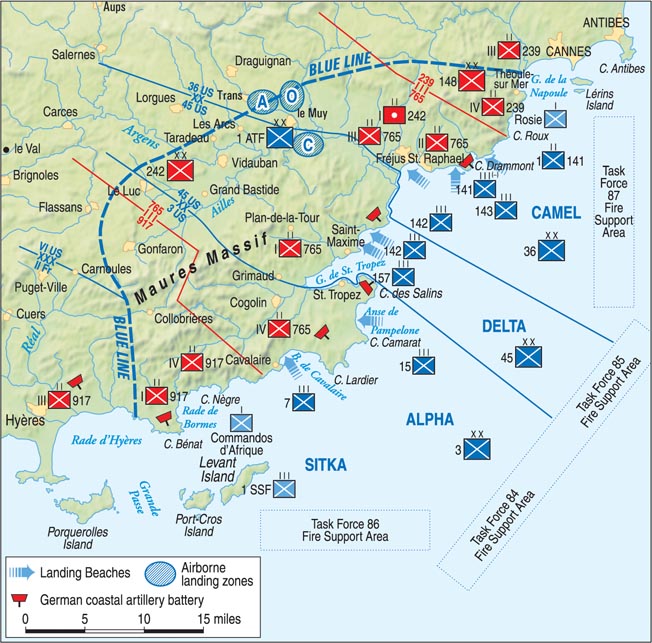

As the paratroopers and commandos did their part, offshore thousands of Americans clambered aboard landing craft. Their assault craft raced for three beaches designated Alpha, Delta, and Camel. The entire operation would be for naught if the landing force did not get ashore and quickly form a beachhead before the Germans could launch their inevitable counterattacks.

The Allied planners divided Alpha Beach into Red and Yellow Beaches located south-southwest of Saint-Tropez. They were defended by the 4th Battalion of the 765th Grenadier Regiment. The 3rd Infantry Division was assigned this sector and it assigned the 7th Infantry Regiment to Alpha Red, while the 15th Infantry was given Alpha Yellow. The 30th Infantry was held in reserve.

The shore bombardment began before dawn as minesweepers cleared channels in the water. A new technique, seeing its first use in combat, was the Apex craft. These were Higgins boats filled with explosives. Just after 7 am these radio-controlled drones hit the obstacle belts along the beach and exploded. Some succeeded in tearing large gaps in the concrete obstacles. Next, rocket-armed craft moved close to shore and launched salvos of screaming projectiles at the beaches. These were intended to detonate the minefields.

After the obstacle-clearing explosives had done their work, the landing troops pushed toward shore, led by Duplex Drive (DD) M-4A1 Sherman tanks from the 756th Tank Battalion. At Alpha Red one of the tanks struck a mine and sank, but the other three reached shallow water and opened fire on German emplacements. Behind them 38 landing craft carried the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 7th Infantry Regiment (2/7 and 3/7) to shore against the sporadic rifle and machine-gun fire of the defenders. At Alpha Yellow the landing craft actually passed the tanks, swamping one in their wakes. A second tank struck a mine as it climbed onto the beach. The troops of the 15th Infantry rushed ashore but found little resistance as many of the enemy soldiers soon surrendered. The 1/15 soon headed for high ground near the town of Ramatuelle while the other two battalions advanced toward Saint-Tropez. When they reached the outskirts of the town, they found most of it was already in the hands of Allied paratroopers and French Resistance fighters. Only one German unit was still fighting. Its tenacious soldiers had dug themselves deep into the town’s old citadel. The 15th joined the attack, and by mid-afternoon the Germans surrendered.

All things considered, the 3rd Infantry Division had a relatively easy day, though they suffered a number of casualties from mines, including two landing craft that struck the deadly devices offshore. The division took 1,627 prisoners that day, most of them Ost troops from Russia, Poland, and Turkmenistan. They had little stomach for a fight against the superior firepower of the Allies, even though they were led by German noncommissioned officers and officers.

Delta Beach was the responsibility of the 45th Division. It was north of Saint-Tropez across a small gulf named for that town. A few miles southwest of the landing area was the town of Saint-Maxime. The entire zone was defended by the 1st Battalion of the 765th Grenadiers and a battery of coastal artillery. Delta was subdivided into four objectives and received much the same preparatory fire as Alpha Beach.

From the American perspective, the two left beaches, Delta Red and Delta Green, were the responsibility of the 157th Infantry. Once again, four DD tanks led the assault and while all made it onto the beach they were soon disabled by mines. The first wave of landing craft was fired upon by a single operational 75mm gun that was quickly knocked out by a destroyer. Another bombardment rapidly finished three 81mm mortars that fired from bunkers. This was the beach where Sergeant Williams came ashore and was soon wounded. Once ashore the 1/157 marched inland five miles to the town of Plan-de-la-Tour while the regiment’s other two battalions moved on Saint-Maxime. The 3/157 entered the town and fought quick actions at the port area and the Hotel du Nord but secured the town by sunset.

Delta Beaches Yellow and Blue were assigned to the 180th Infantry. They used a double portion of eight DD tanks from the 191st Tank Battalion. At Delta Yellow on the left, 2/180 quickly got ashore and pushed four miles inland. To the right at Delta Blue, 1/180 soon seized the beach but was stopped by fierce German defenses just two mile up the road leading north to Saint-Aygulf. Between the two battalions, 3/180 took high ground north of the beach. From there, a platoon from the divisional reconnaissance troop moved down the D-25 road and soon linked up with American paratroopers of the 509th near Le Muy. The scouts realized the road was clear so the tanks were redirected to Le Muy where they helped the paratroopers capture the town by late afternoon.

The last beach, the northernmost of Operation Dragoon, was designated Camel. The landing areas for the 36th Infantry Division, which was entrusted with securing it, were on either side of Saint-Raphael. The area was the most strongly defended of the three beaches. The Germans had deployed a number of batteries around the town, including a trio of 150mm destroyer guns installed by the Kriegsmarine at Cap du Dramont. In addition, there also were a dozen 88mm flak guns nearby. A lesser emplacement, which would still have to be cleared, was situated at Saint-Raphael where four French 75mm cannon were installed in casemates. Not all of the batteries were functioning. American strike aircraft had knocked out some 220mm guns the previous week.

As for the German infantry, they were protected in four strongpoints, each boasting two to three platoon-sized bunker complexes whose defenses featured machine guns, mortar, and light cannons. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 765th Grenadiers manned these defenses. To the north, the 4th Battalion of the 239th Grenadiers helped guard the vulnerable coastline.

The northernmost beaches, Camel Green and Blue, were the right flank of the entire landing operation. They were not near the well-prepared defenses around Saint-Raphael but still within artillery range. The U.S. 141st Infantry Regiment assaulted these beaches, meeting only some small arms fire. Their eight DD tanks were launched too far from shore and so did not arrive until after the first Higgins boats. The German fire soon abated and groups of dispirited Ost troops came out to surrender. This had the added effect of decreasing the accuracy of the German artillery, since it now lacked forward observers. As the 141st secured the beach and high ground farther inland, the 143rd Infantry came ashore and attacked west toward Saint-Raphael. One battalion, 2/143, ran into the bunkers of Strongpoint Lowe on the east side of the town and was soon stopped.

The job of taking Camel Red fell to the 142nd Infantry, but the landing was purposely delayed until the afternoon. The beach was surrounded by the German strongpoints in Saint-Raphael, and the unit had been instructed to wait until its fellow regiments could put pressure on the town from the east. U.S. Navy minesweepers swept the channel leading to the port in the late morning. German heavy artillery fire forced them back, but 90 B-24 bombers unloaded 200 tons of bombs to silence the guns. When the minesweepers went back in, though, they again took heavy fire.

The U.S. Navy launched a number of Apex boats toward the beach defenses. While they worked decently at Alpha Beach, here most of the drones malfunctioned. Several even turned back toward the invasion fleet and had to be sunk by destroyers. The ships then resumed bombarding the Germans until the first wave of landing craft approached the beach. Despite the heavy shelling the German artillery proved as heavy as before so the landing force commander, Navy Captain Leo Schulten, stopped the operation and called his superior, Rear Admiral Spencer Lewis. When Lewis was unable to reach the 36th Infantry Division headquarters ashore he made the decision to land the 142nd at Camel Green and abandon Camel Red. The landing force went a few miles north and put the regiment ashore at mid-afternoon.

Truscott was not happy about the delay, but he did not know about the heavy German defenses. The move undoubtedly saved the lives of many soldiers and sailors, who may have gone into a beach every bit as bad as “Bloody Omaha” at Normandy two months earlier. It was also a credit to the leaders on the spot, who avoided a disaster by quick thinking and improvisation.

All things considered, the amphibious landings on August 15 went extremely well. The Allies suffered 95 killed and 385 wounded on the first day. Tens of thousands of troops were ashore and many had already linked up with the airborne formations inland and captured key towns on the coast. Although it was by no means an easy day, for men were still fighting and dying, the landings went better than expected, with far fewer casualties than during previous amphibious assaults in the war.

On the German side, confusion reigned as reports flooded into the headquarters of both Army Group G and AOK 19. The deception operations made it difficult to determine the focus of the Allied assault. Also, the French Resistance fighters made numerous attacks on the German communications networks, succeeding in cutting those of Army Group G and AOK 19 by 8 am. For a time General Wiese even had to rely on reports from a German headquarters in Italy. Allied paratroopers also cut communications with local units.

The situation actually worked to the advantage of Blaskowitz, who knew he could not stop the Allies but would likely be ordered to stand and die in place by Hitler. Under the guise of preparing for a counterattack, he instead began moving units away from the coast toward the Rhone Valley for the inevitable withdrawal north. He also issued orders to divisions farther west, as he had no local reserves. Infanterie-Division 338 was preparing to leave for Paris and that ordered was cancelled. Infanterie-Division 189’s commander, Generalmajor Richard von Schwerin, was told to form a battle group taken from local units to counterattack the Americans at Le Muy. This would also relieve the 62 Korps Headquarters, which was cut off at Draguignan.

The only other significant counterattack came that evening when German Do-217 medium bombers dropping guided missiles attacked Allied shipping off Saint-Raphael at 6:30 pm. Several of the Allied ships had newly mounted jammers to combat these sophisticated weapons, but the German pilots simply stayed close to their weapons after launch to burn through the jamming. It was a difficult and dangerous mission, but the Luftwaffe pilots rose to the challenge. A missile from one of the bomber’s sank the American landing ship LST-282.

By the next morning, von Schwerin had a battle group of four infantry battalions advancing on Le Muy. The battle group swept aside a paratrooper outpost near Les Arcs at 7:30 am and continued the attack; however, the 517th Parachute Infantry was reinforced by 2/180 and a platoon of M10 tank destroyers from the 645th Tank Destroyer Battalion. As the Americans advanced out of the Saint-Raphael beachhead, they cut off the Germans and engaged them in an all-day fight around Les Arcs.

After nightfall, the Germans withdrew, having suffered 50 percent losses. The following day the 36th Infantry Division relieved the paratroopers at Le Muy. Although the rest of the invasion force spent August 16 securing high ground against expected counterattacks, the 36th reduced German defenses in several towns. One of its battalions, 2/141, overran a German battalion trying to attack the beachhead. Other German units could barely move due to incessant Allied air attacks and the previous destruction of the bridges.

During the night of August 16-17, the high command of the German Armed Forces (OKW) realized the situation in southern France was hopeless. Combined with the continuing disaster in the Falaise Pocket and the swift advance of Patton’s Third Army toward the Meuse River, Operation Dragoon threatened to cut off all troops in the region. If these formations were lost, the German border would be left unguarded. OKW advocated withdrawing Army Group G north toward Dijon. To everyone’s astonishment, Hitler agreed. On this occasion, he abandoned his customary demand that there should be no retreat; however, he did stipulate that German troops remain behind to defend several key Atlantic ports.

As the Germans prepared to retreat, Truscott’s VI Corps pressed its advantage, attacking against light resistance. As some German units withdrew toward their escape route through the Rhone River Valley, a few made feints designed to delay the American advance. The leading American units were very mobile, though. U.S. infantry divisions would assign all available trucks, tanks, and tank destroyer to a battalion of each regiment, giving them speed and firepower. The VI Corps was advancing so rapidly it threatened to cut off not only the Rhone Valley, but also surround the valuable ports of Toulon and Marseilles.

Adding to this American blitz, Truscott ordered Task Force Butler, his mechanized force, to advance past Draguignan early on August 18. They were aided by the French Resistance and soon were across the Verdon River. The scattered German units, mostly police troops, could do little and were soon surrounded at Digne. Most were unwilling to surrender to the French after their own brutality during the occupation, but that evening they yielded to Task Force Butler; afterward, the Americans resumed their advance.

The next major objective was the city of Grenoble, which was the headquarters of the German Reserve-Division 157. As the Americans approached, Generalleutnant Karl Pflaum received contradictory orders. One order instructed him to defend the area until August 30, but the other one instructed him to withdraw into the passes along the Franco-Italian border. Pflaum decided to withdraw to the border, which left the east flank of Army Group G’s retreat unguarded. With the way left open to Grenoble, the Americans seized it on August 22.

The Americans regularly intercepted messages from the OKW to the field forces, and therefore they knew that no German counterattack was expected. The French troops were massing for attacks on Toulon and Marseilles, but the French leadership refused to parcel out any of their units for they wanted to keep them together. The Allies needed the ports to supply the rapid advance, so they ordered the Airborne Task Force and 1st Special Service Force to block the Alpine passes to Italy and prepared to exploit the gap in the German flank. But it would take the Allies time to build up the forces for the operation.

Army Group G also was preoccupied with making plans for the coming days. The Germans intended to use most of their forces to conduct a fighting retreat up the Rhone Valley. The plans called for the 11th Panzer Division and Infanterie-Division 198 to occupy successive defense lines to delay the Americans. At the same time, the German divisions holding Toulon and Marseilles would be sacrificed in order to delay the Allied pursuit.

Toulon and Marseilles were enveloped by the French II Corps beginning August 16 with reinforcement arriving two days later. The French infantry divisions prepared to attack while their armored division was divided into combat commands to reinforce the infantry. An initial assault was made against a fortified German position at Hyeres, just east of Toulon. The town was defended by a battalion of mostly Armenian Ost troops. The defense centered on the Golf Hotel, which fell on August 21; however, 150 Germans held out in a small fort until the following day.

French infantry and armored forces began their attack on Toulon on August 19. The defending Infanterie-Division 242, bolstered by naval and Luftwaffe troops, had a number of fortresses and an old powder magazine under its control. Most of the German coastal guns could not point inland against land targets. They were systematically knocked out by Allied naval and air forces. Fighting was slow and deliberate. By August 24 most of the German-held forts had surrendered. Axis troops entrenched on the Saint-Mandrier peninsula were the last to surrender on August 28. The port was demolished, but American engineers had it partially operational within a few weeks.

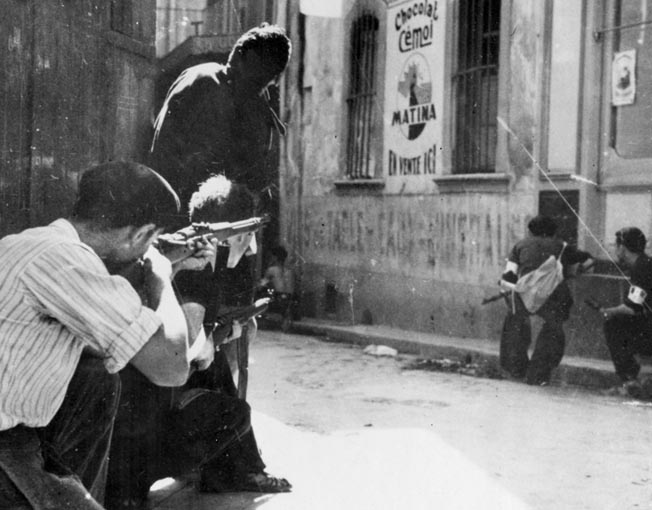

The Allies quickly enveloped Marseilles as well. The 13,000 defenders, mainly belonging to Infanterie-Division 244, received fire not only from regular French forces, but also from resistance fighters who rose up around the city. Although the resistance fighters were unable to stage major assaults, the Germans were unable to stamp them out. French military forces reached the city center on August 23, but it took them four more days to secure the city. Approximately 11,000 Germans surrendered. U.S. engineers had the port operational by September 30.

The crucial engagement of Operation Dragoon unfolded on August 21 in the Rhone Valley. The Germans were continuing their withdrawal northward, but they made the mistake of leaving their eastern flank open. Task Force Butler was sent through that gap to block their retreat at Montelimar. It was a risky move as the task force would be on the end of a long supply line, but the opportunity to block the retreat of Army Group G warranted the gamble. But the task force lacked the requisite fuel supply to accomplish its mission. Nevertheless, it was able to get several hundred troops and a handful of tanks atop Hill 300, which overlooked Route 7, the main road along which the Germans were retreating. The Americas dug in and called for ammunition and reinforcements. They were soon reinforced by the 36th Infantry Division.

The Germans were stunned by the sudden appearance of the Americans. Wiese sent the reconnaissance battalion of the 11th Panzer Division to dislodge them. The scout troops succeeded in cutting off the Americans holding Hill 300, but only temporarily. The 141st Infantry Regiment arrived next and formed a perimeter, but the Americans were reluctant to attack until their position was more secure. The Germans, who were plagued by traffic jams and enemy aircraft, also had trouble getting their forces into position. Nevertheless, most of the 11th Panzer Division was in place by August 24. The Germans repulsed an American attack into Montelimar that day, and a German counterattack cleared Hill 300. Afterward, the Germans formed a provisional corps from several divisions and regiments with which to attack the two American regiments near Route 7.

The German counterattack began on August 25. One German battle group was able to penetrate the U.S. cavalry screen to threaten the 36th Infantry Division’s supply line, but that was the only success that day. The other five battle groups were beaten back by a combination of American infantry and artillery and Hill 300 was retaken. The 1/141, which was supported by 11 armored vehicles, cut Route 7 for a few hours, but a German night attack reopened the road after midnight. The fighting was so heavy the 157th Infantry and 191st Tank Battalion were rushed to the scene as reinforcements. The next two days were essentially a stalemate; neither side was able to gain the advantage. Unable to push back the Americans, many German units were sent north by crossing the Rhone River and moving up the west bank. Some German forces stayed behind as rear guards but by August 31 the fighting at Montelimar was over. The Germans lost 10,100 men killed, wounded, or captured, while the Americans lost 1,575 killed and wounded. Neither side could truly claim a victory.

After Montelimar the Germans continued their flight northward with the Americans and French in pursuit. A few skirmishes and small battles were fought, and the Allies took more German prisoners, but eventually the Axis forces withdrew north of Lyon. They fell back on the Vosges Mountains on the Franco-German frontier where the whirlwind Allied advance finally ground to a halt. The Seventh Army sent out patrols that linked up with Patton’s Third Army on September 10. As many as 20,000 Germans cut off behind Allied lines surrendered five days later.

All things considered, Operation Dragoon was a resounding success. Many of its problems, such as a lack of fuel to exploit the pursuit and a shortage of armor and mobile units, were due to how quickly the VI Corps was able to take the offensive after landing.

The Allies had liberated southern France at a relatively small cost of about 9,000 American and French casualties, compared to about 157,000 for the Germans, mostly in prisoners. The rapid advance prevented the Germans from launching any counterattacks into Third Army’s southern flank; however, the Germans were able to save some troops for the defense of Germany.

Operation Dragoon is often referred to as the Champagne Campaign due to its relative ease, but this is an oversimplification. Allied troops spilled their blood, as did French Resistance fighters. It was a boon to the Allied cause that the cost was not higher.