The Lakota were one of four major branches of the Native American peoples known as the Sioux. They were forced to shift west in the 17th and 18th centuries when their Native American enemies, one of which was the Chippewa, received firearms from French traders. While the easternmost Dakota branch remained on the upper Mississippi River, the two central Nakota branches settled on the upper Missouri River, and the westernmost Lakota branch went into the Black Hills and Badlands.

The Sioux Wars, which began shortly after the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, lasted for nearly a half century and can be divided into five separate wars. A decade after the treaty, the Lakota increased the frequency of their raids against wagon trains and frontier outposts as they became increasingly angered by the high volume of traffic on the Oregon and Bozeman Trails.

The increased traffic was the result of the discovery of gold in the Montana Territory. The Bozeman Trail cut straight through prime hunting grounds of the Teton bands. Chief Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa band, Chief Red Cloud’s Oglala band, and Chief Spotted Tail’s Brule band all deeply resented the traffic on the Bozeman Trail.

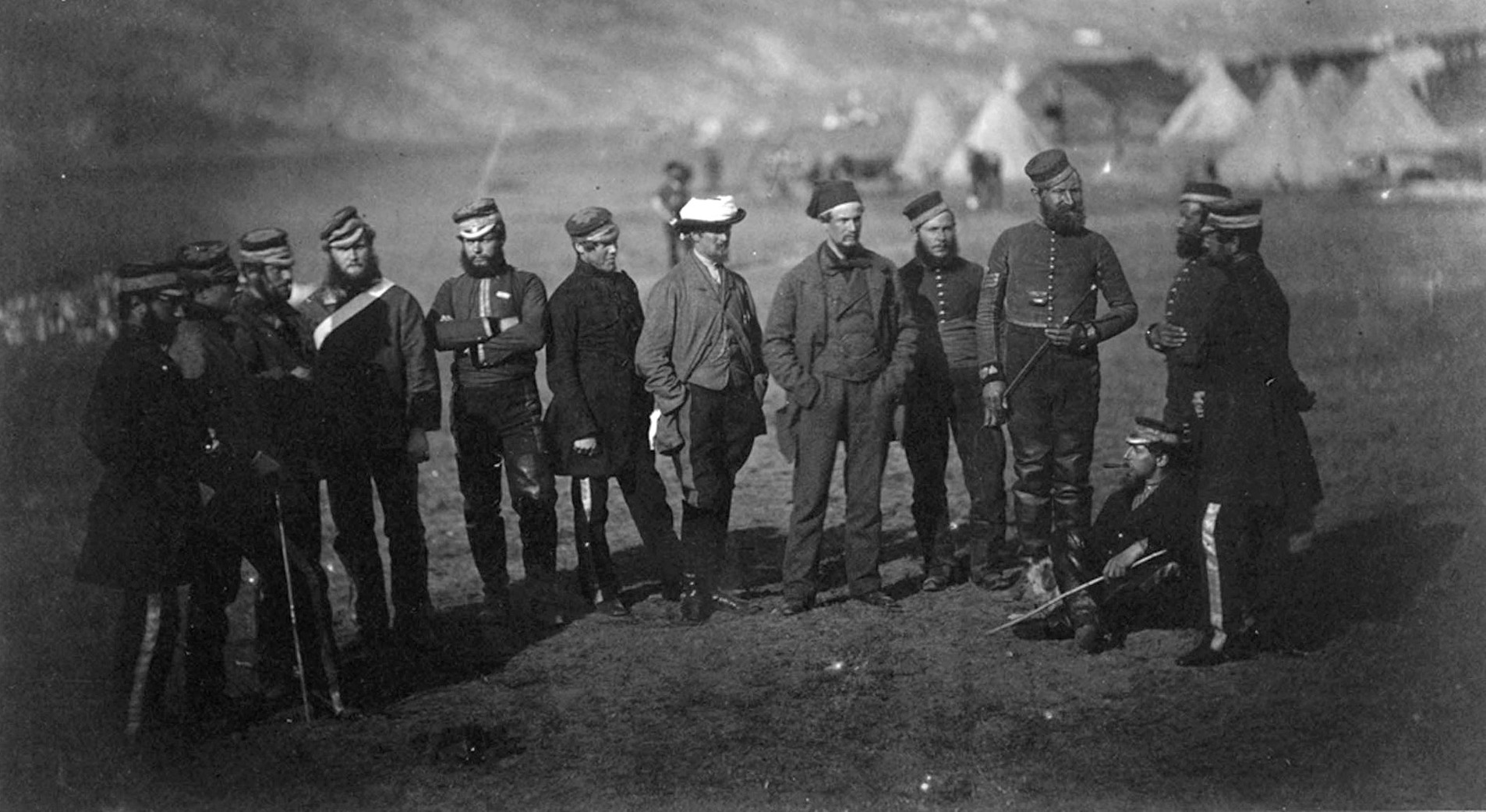

In the winter of 1863-1864, U.S. Cavalry Lieutenant Caspar Collins spent considerable time with the Oglala tribe learning about their way of life and participating in buffalo hunts. Collins’ men, many of whom had fought for the North in the Civil War, were eager to fight the Lakota. The young lieutenant did everything in his power to restrain them. It was a wise decision given that the few garrisons in the region were heavily outnumbered by the Tetons and their allies.

When the War Department requested a count of the Native Americans in the vicinity of Fort Laramie, Collins reported there were hundreds of Lakota and Cheyenne lodges near the Platte River and perhaps 3,000 warriors in the region.

“All of the Indians are just now liable to become hostile,” he wrote. Collins reminded Washington that conflict was a natural state for the tribes. “Every tribe has some hereditary enemies with whom it is always at war and against whom it makes regular expeditions to get scalps and steal ponies,” he wrote.

Platte Bridge Station was situated 130 miles west of Fort Laramie. When the commanding officer at Fort Laramie learned in mid-July 1865 that five empty wagons were returning east along the Oregon Trail toward the Platte, he sent Collins with a detachment to locate the wagon train and escort it to the fort.

Meanwhile, Oglala chiefs Young Man Afraid and Red Cloud and Northern Cheyenne Chief Roman Nose were plotting an attack on the small garrison at Platte Bridge Station. Their objective was to cut the U.S. Army communications with points west.

Collins led his 20-man detachment west for three days to Platte Bridge where they bivouacked. On July 26 Collins led his detachment across the bridge spanning the Platte River and continued west. They had gone no more than a mile when hostiles emerged from multiple hiding places and encircled the troopers. A swirling melee occurred with the Oglala and Cheyenne using their spears and tomahawks rather than their deadly bows. Collins was slain while trying to assist another trooper. Of the cavalrymen engaged, four were slain and all the survivors were all wounded, some severely.

The survivors located the wagon train and endured a second round of fighting against the hostiles. Command devolved to Sergeant Amos Custard, who circled the wagons. The troopers and armed civilians repulsed multiple assaults by the Oglala and Cheyenne. The attackers eventually withdrew having suffering heavy losses. The action foreshadowed the much more devastating Fetterman Fight the following year during Red Cloud’s War of 1866-1868.

—William Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments