By David A. Norris

In January 871 Alfred, prince of the Saxon kingdom of Wessex, waited for his brother in the tense moments before battle. The prince gazed at a formidable host of Viking warriors assembled on high ground at Ashdown, in Berkshire. For six years, “the Great Army” of Viking raiders had roamed nearly at will across the Saxon kingdoms of England. Towns, villages, monasteries and convents had all been captured and destroyed, their inhabitants slaughtered. Most of Saxon England had fallen and tottered on the edge of ruin. Alfred’s brother, King Aethelred, ruled the last lands able to offer any resistance to the Vikings.

The young Prince had yet to make his mark on the battlefield and grew impatient waiting for his brother to arrive. Giving way to his impetuous nature, the Alfred ordered his men into battle, leading them against the vast army led by two infamous Viking kings—and, as it turned out, into the pages of British history.

Born at Wantage, Berkshire in 849, Alfred was fifth son of King Aethelwulf, ruler of the West Saxons. When Alfred was born, seaborne raids against the Saxon lands of England had been going on for some 60 years. Split into several separate and competing monarchies, the Saxons struggled to repel the raiders sailing in from the North Sea. Usually called “Vikings” today, 9th century chroniclers called the invaders Danes, pagans, heathens, or pirates. Most of the men attacking the British Isles came from what is now Denmark and Norway.

Abandoned by the Romans in the early 5th century, Britain fell to invading Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Soldiers from these Germanic tribes from northern Europe had been invited as mercenaries by the late Romans. More and more arrived, and pushed aside or absorbed the native Britons to take over most of what is now England. These Germanic Britons were later referred to as the Anglo-Saxons.

At one time a dozen or so Anglo-Saxon monarchies competed for power in early medieval England. Wessex, the kingdom of the West Saxons, was in southern England. At the time Alfred the Great was born in 849, Wessex included most of England south of the Thames, and some of the Cotswolds and other lands of western England out to the boundaries of Wales. It was the most powerful of the English kingdoms, the other three remaining then being Mercia, East Anglia, and Northumbria. The military forces of the English kingdoms were scattered and took time to assemble for war. The kingdoms also jostled each other for power, and sometimes faced internal political strife.

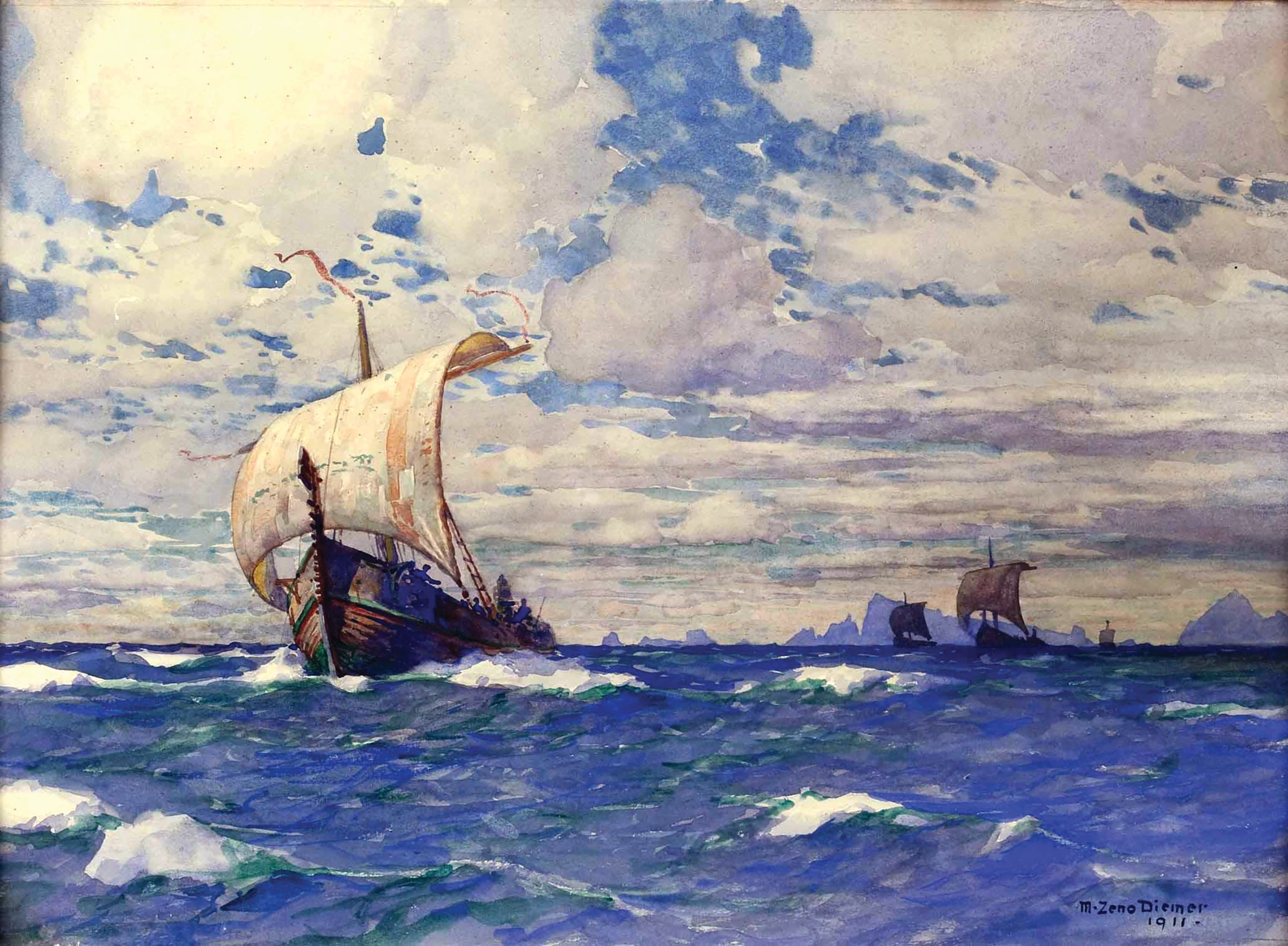

The Danes had great advantages over the lumbering armies of England and northern Europe. They plied the seas in longships, swift shallow-draft vessels propelled by oars as well as a large square sail. Under oars, the vessels could reach speeds of 12 knots or more, and could easily overtake or outrun any vessel they might encounter.

Longships drew three feet of water or less. Their crews could run the ships aground close to a beach and wade ashore. Likewise, when the crews returned laden with loot or prisoners, the ships could be pushed out to sea in a few minutes. It was possible for raiders to transport the longships overland and launch them in rivers or lakes, surprising Saxon towns and villages far from the coast.

While keeping a wary eye on the Danes, King Aethelwulf wanted to make a pilgrimage to Rome. Although they were on the northwest edges of Europe, the West Saxons were well acquainted with Rome. In the city, there was even a “Saxon School” for the education of their clergy. Unable to leave his realm in 853, the king sent his young son Alfred to meet the pope. Alfred was only about four at the time. When Aethelwulf deemed it safe to leave his kingdom for a time in 856, he journeyed to Rome and brought Alfred with him.

Many noblemen of 9th century England could not read, and saw little need for books. Alfred was different; although not taught to read in his early childhood, he developed a lifelong affection for books.

King Aethelwulf died in 858. His kingdom was divided between his son Aethelbald, who received his western lands in Wessex; and Aethelbert, who would rule Kent and the other eastern regions of his domain. After Aethelbald died in 860, the old kingdom was reunited under the rule of Aethelbert. Under an agreement among the royal family, his younger brothers Aethelred and Alfred were placed next in line of succession rather than any sons of Aethelbert.

In 865, Aethelred became king upon the death of his elder brother. The new king worked well with his younger brother, raising Alfred to the rank of secondarius—his second in command and heir apparent. He gained experience as well as respect as he took part in frequent clashes with the Danes.

Aethelred assumed the crown at a crucial moment in England’s history. For decades, the Danes were content with extended raids that ended once they had gathered enough loot, or had been bribed with suitably large payments to withdraw. With royal authority divided among multiple kingdoms, it was difficult for the Saxons to assemble and maintain the military force needed to repel the invaders, or prevent more incursions.

But just as Aethelred became king, England’s situation grew infinitely worse. A massive number of Northmen, called “the Great Army” in English chronicles, landed in East Anglia in autumn 865. No longer satisfied with plunder and extortion, many of the Danes would settle permanently on land seized from the English. Wrote chronicler Simeon of Durham, “there was this countless host horsed, and rode and trampled hither and thither, taking very much spoil, and sparing neither man nor woman, widow nor maiden.”

King Osbert, ruler of the neighboring kingdom of Northumbria, was overthrown and replaced by a new king, Aella. When the Danes poured out of East Anglia into Northumbria, the two rivals united to lead an army against the invaders. They attacked the Danes who had captured the city of York. In the battle, the Northumbrian force was defeated and Aella and Osbert were slain. The shattered kingdom came to peace terms with the Danes.

With East Anglia and Northumbria unable to help allies or resist the invaders, the “Great Army” next wore down Mercia, the kingdom to the north of Wessex. In 869, the Danes moved back into East Anglia. The next year, the Danes defeated the East Anglians. Their ruler, King Edmund, was either slain in battle or was captured and killed by the enemy.

Fighting in 9th century Britain was done mainly on foot. Horses were of much less importance in battle at this time than they would be to knights several centuries later. The Danes could transport horses in their long ships, but usually found it more convenient to seize mounts and draft animals in lands they plundered.

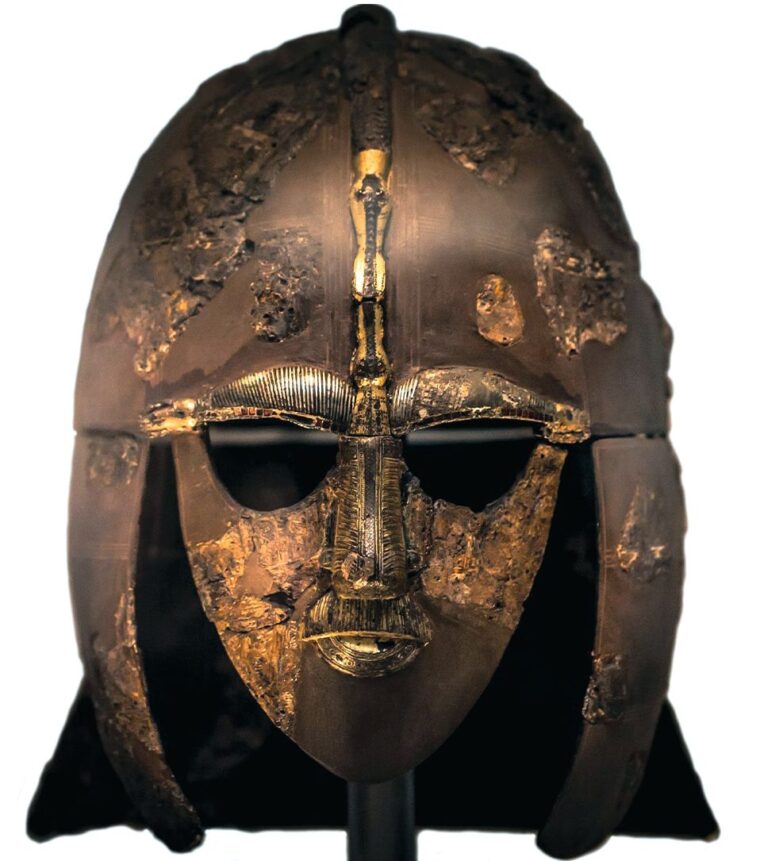

The Saxons used spears, including lighter throwing spears as well thrusting spears, which could be wielded as pikes. Among the Saxons, swords were used mainly by higher-ranking classes, although nearly everyone carried a knife into battle. Axes, sometimes the same ones the men used on their farms, also served as weapons. The axe was a more important weapon among the Vikings.

Shields were generally of hardwood, sometimes protected with layers of ox hide or leather. A metal boss (usually iron) in the center of the shield protected the hand grip. Saxons and Vikings alike fought in formation behind a shield wall, with each man’s shield adjoining or overlapping that of his neighbor. It made an effective defense, but such formations would be broken up if the soldiers had to rush in pursuit of an enemy.

Armor of chain mail was known, but rare and expensive enough to limit its use to the wealthiest warriors. Many men would have worn their ordinary clothing, perhaps adding a heavy padded leather jerkin to provide some protection.

Contemporary English accounts of these Viking-age battles have few details, but they describe massive and horrific casualties. Saxon armies lost capable leaders and great numbers of trained fighting men, weakening their responses to future raids. But the Danes by no means had everything their own way; some Viking forces suffered astounding losses in disastrous defeats. But, there were always enough Northmen to fill fleets of new ships to cross the North Sea and attack the Saxons.

By 870 Aethelred’s Wessex was the only kingdom free of the Danes. In the closing days of that year, the army of Danes (Saxon chroniclers called them the “heathen host”) reached the town of Reading in Berkshire. Sheltered in a fortified encampment, they sent out a foraging party under two jarls, or chieftains.

Ethelward, another Saxon chronicler whose writings of the “age of Alfred” survive, wrote of the Danes at Reading that “their two chieftains were proudly prancing about on horseback, though naturally unskilled in the art of riding, and, forgetful of their seamanship, went galloping over the fields and through the woods.”

On or about the last day of 870, at a place called Englefield, the foragers ran into a Saxon force led by Aethelwulf. This man, bearing the same name as the late king of Wessex, was the ealdorman of Berkshire. At this time, an ealdorman was an official appointed by the Saxon king to administer one of his counties; the term is related to the Viking rank of jarl or chieftain, as well as the modern ranks of British earl as well as city alderman. Ealdorman Aethelwulf led his small force to a resounding victory. They slew one of the enemy earls, and the Danes fled from the field.

Englefield was only the first of a series of grueling clashes in what the chroniclers called “the Year of Nine Battles” (not all of the names of the battles survived in the records) that shook Wessex in the next year. About four days after Englefield, King Aethelred and his brother Alfred brought the kingdom’s main army to recapture Reading. In a hard-fought but disastrous battle, the Saxons pushed their way to the town gates, but the Danes burst out of the town for a surprise counterattack. The Saxon ranks collapsed. The capable Ealdorman Aethelwulf was killed with many more of Aethelred’s men.

Yet, only another four days passed until there was another pitched battle at Ashdown on or about January 8, 871. Ashdown’s exact location is uncertain, but it’s thought to have been in Berkshire. Bagsecg and Halfdan, remembered as leaders who landed with “the Great Army” of 865, led the Danes to a commanding stretch of high ground at Ashdown. They divided their army, with one part led by the two kings and the other under the command of several jarls.

King Aethelred and his brother were attending mass when the Danes approached and threatened battle. Alfred left to keep the enemy under observation. Aethelred, as Asser recorded, refused to cut short the service, declaring “that never while he lived would he leave his Mass before the Priest had ended it, nor, for any man on earth, to turn his back on Divine Service.”

On what soon became the field of battle, the Danes divided into two forces, one under the two kings and the other commanded by several jarls. The Saxon planned a similar strategy, with Aethelred leading his half of the army against Bagsecg and Halfdan, and Alfred attacking the jarls.

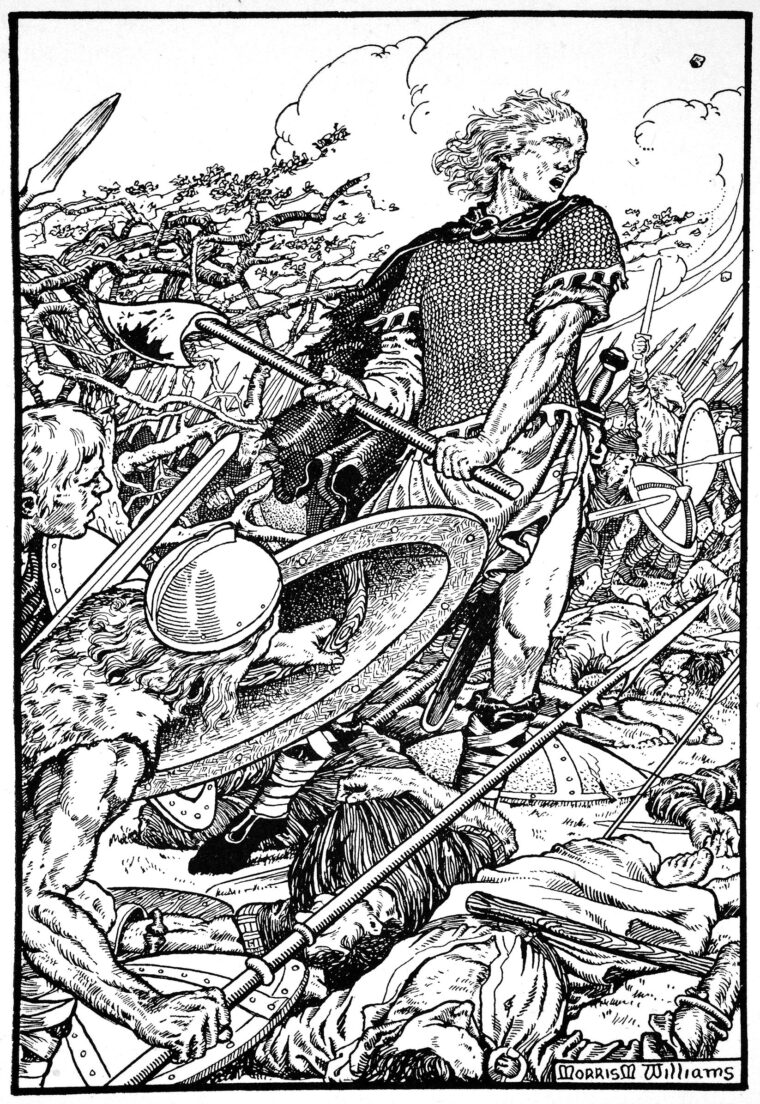

The Danes advanced steadily toward the Saxons. Alfred was still in command on the field, and he watched the enemy draw so close that he either had to retreat or charge. Able to wait no longer, “so drew he together his shield-wall in good order, and advanced his banner straight against the enemy.” As Prince Alfred wielded his sword and shield in the melee, “This way and that swayed the battle for a while, valiant it was and all too deadly.” When the king’s mass was done, Aethelred rushed to the front with his reserves. The Viking army broke. “Most part of their force were slain, and with all shame they betook them to flight.” And so the Saxons held “the death-stead,” as they called the battlefield. Among the dead were Bagsecg and a number of the Danish jarls.

Ashdown was something of a Pyrrhic victory for the Saxons. Enough men were lost or put out of action that shortly afterwards their weakened army suffered losses in the battles of Basing and Merton. Aethelred died shortly after the latter battle. It’s uncertain whether he had been mortally wounded on the battlefield, or succumbed to some form of disease. At any rate, the throne was passed on to Alfred.

More Danes joined the Great Army. The new king endured more defeats by the combined enemy forces. And yet, King Alfred’s resistance was so fierce that the Northmen negotiated a truce.

The invaders left Wessex, but only to fall upon the remnants of the other English kingdoms and to take London. In 872 Burghred, king of Mercia (and Alfred’s brother-in-law) was forced into exile and would die in Rome. A Mercian named Ceolwulf was installed on the throne as a puppet ruler; it was understood that he would abdicate whenever it suited the Danes to bring in a different king.

Alfred kept up resistance even as more Danes poured into eastern England and Scotland. Chronicler John of Wallingford wrote of the years of chaos, “In such storm of events, who can track the course of each wave?”

Firmly based in conquered lands in East Anglia, the Danish Jarl Guthrum led an army against Wessex in 876. The invaders eluded pitched battles. Although the Danes accepted bribes to move on, they simply plundered another area until they were paid off again.

John of Wallingford described the “piteous … slaughter that might be seen” in the wake of a Viking attack. “There they lay in each road and street, and crossway: old men with hoar and reverend locks, butchered at their own doors; young men headless, handless, footless; matrons foully dishonoured in the open street, and maidens with them; children stricken through with spears—all exposed to every eye and trodden under every foot. Some, too, there lay half burnt under their half-burnt houses, not having dared to leave them; for they who were driven from their hiding-places by the fire perished by the sword.”

Late in the year, King Alfred and the royal household were at Chippenham in Wiltshire. Like other Saxons, the king’s retinue looked forward to Christmas as a time of celebration. Normally, the Danes were quiet during the winters. The celebration lasted through the 12 days of Christmas. Early in January 878, stated the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “after twelfth-night, the Danish army stole out to Chippenham.” Led by Guthrum, the invaders surprised the Saxons guarding the household of King Alfred. With their stronghold fallen, Alfred and his family escaped with some of their retainers. The raiders killed or scattered the soldiers who had been with the Saxon king.

Guthrum hoped to conquer all of Wessex, and his triumph looked nearly complete. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that after the Danes overran Chippenham, “many of the people they drove beyond the sea, and of the rest the greater part they subdued and forced to obey them, except for King Alfred” and “a small band.” Once, Alfred’s kingdom stretched 300 miles from the western tip of Cornwall to Kent on the southeast coast of England. Now, he reigned in hiding over a fragment of Somerset forest and marshland, and remote scraps of neighboring counties that so far escaped the marauding Danes.

From the desperate situation of the king of Wessex at the low point of his fortunes arose some of the most famous legends of Alfred the Great, and indeed, in all of English history. Perhaps the most famous tale is the one of King Alfred and the cakes. In this story, the king was alone and in hiding. A peasant woman offered him shelter as she might a poor vagrant, having no idea of her guest’s once-exalted station. Busy with her chores, the woman told Alfred to watch some wheat cakes she left baking at the hearth. Alfred was so deep in thought about rescuing his kingdom that he didn’t notice the cakes burning. When her benefactor returned, she was astounded by his negligence and scolded him.

Some of Alfred’s subjects fled across the English Channel to France. To those who remained alive Alfred seemed to have dropped out of sight. It would be some time before he would be in any position to go on the offensive. It hardly seemed possible for affairs in Wessex to be any worse, until the Danish chieftain Ubba sailed from his winter camp on the South Welsh coast. Thirty ships full of Danish warriors landed on the north coast of Devon.

Odda, the ealdorman of Devon, refused to throw in his lot with the invaders. Little help was available, but Odda cobbled together what forces he could, most of the men being peasants with little or no military experience. They assembled at a place remembered as Countisbury Hill, which offered some existing defenses in the form of an ancient fort that overlooked the beach that swarmed with Ubba’s men.

Ubba postponed attacking Odda. He knew that the Saxon position had no water. There seemed to be ample time to wait for thirst and hunger to bring them an easy victory.

The symbol of Ubba’s power was a flag, sewn by his sisters that depicted a raven. With the raven, a symbol of the Danes’ chief god Odin, the banner was believed to have magical powers. Many believed that the flag could predict the outcome of a battle; if the cloth flapped and waved in the wind, it meant victory. Should the cloth folds droop on the staff, defeat was foretold.

Rather than wait for a slow defeat, Odda rolled the dice for a surprise dawn attack. His men rushed over their ramparts and charged into the Danish camp. Taken by surprise, Ubba’s army was destroyed. Ubba himself was killed; some say that Odda slew him. The once-fearsome raven flag was now a trophy of war.

After Easter, Alfred found refuge at Athelney, an island with a hunting lodge or small royal hall surrounded by marshlands, in modern-day Somerset. This island of “firm land, which is only two acres in breadth,” was described two and a half centuries later by the historian William of Malmesbury. “Athelney,” said the historian, “is not an island of the sea, but is so inaccessible on account of bogs and the inundations of the lakes that it cannot be got to but in a boat. It had a very large wood of alders, which harbors stags, wild goats, and many beasts of that kind.” Alfred probably knew the area well from hunting trips he took in happier times.

Athelney offered a secure and secretive base to conduct raids against the Danes. In this way they supported themselves with food and supplies taken from the invaders, as well as Saxons who had surrendered to them. William of Malmesbury wrote of Alfred that even when the enemy thought he was finished, “he would escape like a slippery serpent, from the hand which held him, glide from his lurking-place, and, with undiminished courage, spring on his insulting enemies.”

In the beginning, Alfred’s small band made swift raids to seize enough food to ensure their survival. Gradually, the foraging expeditions grew into sharp guerilla raids. Once completely dominant, the Danes were now forced to concentrate their forces to avoid being cut up in small detachments. Small bands of Northmen were no longer everywhere, and many of Alfred’s subjects were able to come out of hiding and prepare for battle again.

After gradually building up his forces, early in May, Alfred left Athelney. He halted at a place known as “Egbert’s Stone” and summoned his subjects and allies to join him. Asser wrote that “And there met him at that place all the people of the districts of Somerset and Wiltshire, and all the people of the land of Hampshire, who had not gone beyond the sea for fear of the pagans. When they saw the king, as was right, they received him after so great tribulation as one risen from the dead, and they were filled with joy unspeakable.”

One of the legends of Alfred the Great told of him going under cover around this time, disguised as a minstrel, into the Danish camp. Whatever the truth of the story, it shows something of the unique regard the people of Wessex had for their king. Not only did they believe he had the imagination to plan the infiltration of the enemy camp, and the courage to conduct the reconnaissance himself, but it was also believable that he could sing and play music well enough to fit the part.

Word spread of the reappearance of King Alfred. From areas of Somerset, Wiltshire, and Hampshire that were free enough of the Danes, men left their homes or hiding places and joined the growing Saxon army. Perhaps beacon fires were lit to summon the men to rally around Alfred.

After leaving the camp at Egbert’s Stone, the Wessex army marched to a landmark known as the Iley Oak, and camped another night. Egbert’s Stone and the Iley Oak were evidently well-known to the people of the region, making it easy for local men to find the king’s army.

The next morning, on a date not exactly known but between May 6-12, 878, Alfred “set his standards in motion and came to the place called Edington,” according to Asser. Guthrum’s army was there in a fortified position. The king of Wessex “fought fiercely against the whole host of the pagans, forming his shield-wall closely, and striving long and boldly.” The tide of battle turned toward Alfred, who “with great slaughter overthrew the pagans.”

Unable to reach the seashore and escape on their ships, Guthrum fled deeper inland with some of his men into Chippenham. Alfred followed, “and smiting the fugitives, pursued them to the fort. And all things, men and horses and beasts, that he found without the fort he took, and the men he slew forthwith.”

Now, the resurgent West Saxons held the advantage, as political and feudal ties would strengthen their forces. On the other hand, the Danes were formidable opponents but they were not united under a single ruler. They raided, fought, and withdrew as they saw fit, and factions formed alliances when convenient. Now, Ubba was dead and his army was destroyed, and no Danish groups were close enough or willing to help raise the siege of Chippenham.

The food for the remnant of Guthrum’s army had been mainly the stolen livestock they herded toward Chippenham. Left to graze in pasture land outside the defenses, the livestock was recaptured by the Saxons. Penned up in the Saxon stronghold they had captured back in January, Guthrum and the Danes endured two weeks of siege before the threat of starvation, and the chance of obtaining mercy, pushed them to surrender to King Alfred.

Edington and the siege of Chippenham were landmark triumphs, all the more impressive following the period of chaos and uncertainty after the royal court was expelled from Chippenham. Neither victory meant an end to the troubles of Wessex. But Guthrum’s defeat meant that the Danes were forced to leave Wessex and its other lands to Alfred, and they even abandoned the western portion of Mercia. The Saxons regained London and rebuilt the city after its ruination by the invaders.

And, there was a truly remarkable concession. Guthrum consented to convert to Christianity. He adopted a Saxon name, Aethelstan. And, his godfather for the christening was none other than King Alfred himself.

The Northmen remained a menace, but Guthrum held to his word. He ruled in East Anglia, but left Alfred’s realm alone. The former Guthrum even minted Saxon-style coins with his new name of Aethelstan until his death in 890.

The agreements reached after the Battle of Edington were formalized some years later (the precise date is unknown) by the Treaty of Wedmore. Watling Street, an old Roman road running diagonally across England, became the boundary between Saxon and Dane. Watling Street ran from Dover and Kent across the Thames at London, and continued into Mercia. To the east would live the Danes, in a land called “the Danelaw,” as their laws were in effect within this region. King Alfred held sway over the lands west of the line.

Wessex still resorted to paying “Danegeld” (Dane-money) to the Vikings as bribes to keep them from raiding the Saxons. Some of the invaders were beginning to settle down and preferred to tend to their new farms rather than go raiding. Yet, all too many Danes continued to accept the “protection payments,”only to break their pledges and go back to war. The rest of Alfred’s reign would not be all peaceful.

That is not to say attackers would have an easy time. Under Alfred’s planning, the Danes faced a much more efficient and deadly foe. The fyrd, or Saxon militia, was divided into two groups. One group was ready to take up arms while the other tended to their farms and harvests, so responding to raids with force was much faster than in previous decades.

A number of important burhs (market towns), were selected as military posts. Some towns had remnants of Roman fortifications that gave a head start in providing defensive walls. Others required new earthworks, ditches, and wooden palisades. Roads linked the burhs. In the event of a new invasion, fire beacons quickly signaled the alarm across the countryside. Lands were granted to settlers who would bear arms in the event of an emergency. When the system went into effect, all of Alfred’s subjects lived within 20 miles of the defenses and soldiers of one of the new burhs.

It was obvious to Alfred that a revamped land militia would not be enough to protect his subjects. Wessex had a small navy in the time of his father King Aethelwulf, but Alfred expanded and strengthened his navy to a higher degree. At that time, the West Saxons and the English were not really seafarers. To man his ships with experienced mariners, he recruited sailors from Frisia and elsewhere along the north European coast.

Nonetheless, wars continued during the rest of Alfred’s reign. Simeon of Durham wrote of an attack in 884. The Danes came to Rochester, and built an earthwork outside the gate of the town. The townsfolk held on, allowing Alfred time to confront the enemy “with no small force”. When the Saxon army “drew near …so quickly did the Danes, fear-stricken, seek safety on Ship-board; leaving their earthwork, and all the horses brought with them from France, and all the French captives they had taken.”

In 896, the “Host” held a stronghold on the River Lea, about 20 miles north of London. A chronicler noted that “a great body of the townsmen, and other folk beside” attacked the Danes but “they were put to flight, and there was slain some four of the King’s Thanes [noblemen].”

Alerted to the incursion, King Alfred encamped by London, watching the enemy and keeping them away from the farmers harvesting the year’s crops. Inspecting the layout of the River Lea, he saw a way that the stream “might be shut in so that never might they bring out their ships.”

John of Brompton left a little bit of detail into Alfred’s plan to trap the enemy fleet. Joined by a force of Londoners, Alfred attacked the stronghold and “brake it down and slew four of their leaders, and divided the river Lea into three branches, so that their ships could not be brought out.” The Danes abandoned their ships in the Lea and withdrew from the London region. After the enemy left, the Saxons burned some of the captured vessels, and took some back to London.

Although constantly occupied with the protection of the realm, Alfred’s travels to Rome and his devotion to books made him well aware of potential alliances with countries on the continent. His daughter Aelfthryth was married to Baldwin II, the Count of Flanders, in 889. This tie would come back to haunt England. The four-times-great-granddaughter of Aelfthryth, Matilda, would become the wife of William the Conqueror —the Norman ruler who would conquer the Saxon kingdom of England in 1066.

Another of Alfred’s daughters, Aethelflaed, married Aethelred, the Ealdorman of Mercia. Allied with her brother King Edward of Wessex, Aethelflaed was skilled at politics. She came to rule Mercia in her own right in an age when it was nearly inconceivable for a woman to reign. In 917, with Edward of Wessex, she campaigned against the Danes and recaptured Derby, although she died the next year.

King Alfred himself died in 899. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle eulogized him thusly, “King he was over all Angle-kin, save only that part which was under Danish sway; and for thirty years, lacking one and a half, held he the kingdom.”

His son and successor, Edward the Elder, inherited a strong kingdom able to survive to become a foundation of England and the monarchy. One millennium later, Alfred was regarded as one of England’s most famous kings, but he was also admired (not entirely accurately) as the founder of the Royal Navy. The rebellious 18th century American colonists also looked to the medieval king of Wessex; in 1775, one of the first warships of the Continental Navy was named the Alfred. To this day, Alfred the son of Aethelwulf is the only king of England whose name is joined with the honorific of “the Great.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments