By Al Hemingway

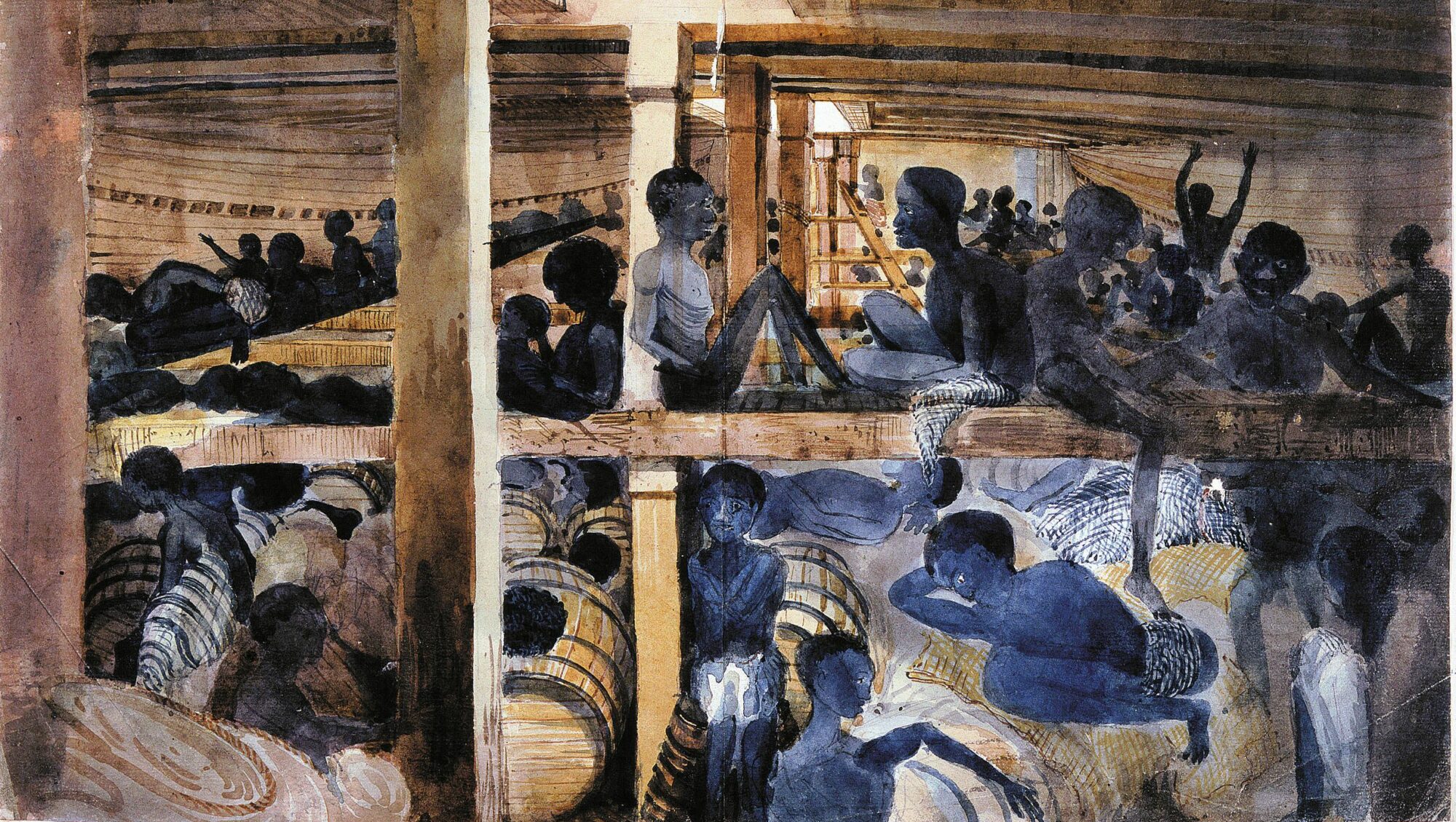

In 1819, the United States Congress passed legislation prohibiting the international slave trade and mandating that anyone apprehended while participating in the sordid business would be put to death. To enforce the new law, the United States Navy established the African Slave Trade Patrol to search the waters off the West African coast for American ships participating in the illegal trade.

Unfortunately, in the wake of the War of 1812, the Americans were still sensitive to any foreign country, especially Great Britain, boarding their vessels and meddling with American shipping. As a result, the Navy withdrew its ships from the patrolling detail, and it would not be until two decades later that a permanent unit would be formed to fight the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

In his new book, Africa Squadron: The U.S. Navy and the Slave Trade, 1842-1861 (Potomac Books, Washington, DC, 2007, 277 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $27.50, hardcover), author Donald L. Canney closely examines the performance of the Navy’s role in interdicting slave ships on the high seas and preventing them from reaching the

In his new book, Africa Squadron: The U.S. Navy and the Slave Trade, 1842-1861 (Potomac Books, Washington, DC, 2007, 277 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $27.50, hardcover), author Donald L. Canney closely examines the performance of the Navy’s role in interdicting slave ships on the high seas and preventing them from reaching the

United States. For the period between 1824 and 1842, American slave traders plied their human trade unimpeded by the U.S. Navy. Ships laden with slaves for the United States sailed to Cuba and Brazil at increased rates. British vessels, however, halted and boarded American ships that they suspected of carrying human cargo for sale to southern plantation owners.

With the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842, the United States once again agreed to supply ships to patrol the African coast. The African Squadron was organized in 1842. To motivate the crews, prize money was offered. For each African rescued and handed over safely to American authorities, crew members were awarded $25 apiece.

Despite the monetary attraction for officers and crews, duty in the African Squadron was miserable. Terrible weather conditions, the Navy’s official indifference, and the apathy shown by the American judicial system frustrated both officers and sailors alike. Although many of the squadron commanders and officers were Southern-born, they carried out their duties enthusiastically. Many of the officers felt pity for the inhumane treatment of the Africans forced aboard the slave ships.

Lieutenant T.A.M. Craven, commanding the U.S. Steamer Mohawk, wrote, “The Negroes are packed bellow [sic] in as dense a mass as possible for human beings to be crowded. These unfortunate creatures are obliged to tend to the calls of nature in this place and here they pass their days, their nights, amidst the most horridly offensive odors of which the mind can conceive, and this under the scorching heat of the tropical sun, without room enough for sleep, with scarcely space to die in.”

During most of its tenure, the African Squadron enjoyed limited success. Ironically, it was not until the late 1850s, under the administration of pro-Southern President James Buchanan, that the unit began to develop into an effective force. Between 1859 and 1860, seven ships were seized, freeing over 4,000 slaves. The last action the squadron was involved in was off the coast of West Africa in 1860 when the USS Marion dispatched a contingent of sailors and Marines to protect American lives and property. Tragically, by then it was “too little too late,” as the United States stood on the brink of civil war.

Despite its good intentions to rid the high seas of the horrible activity, and the Navy’s assistance in establishing the African colony of Liberia with rescued slaves, the unit had a less than shining record. While the majority of commanders attempted to fulfill the mission, many of the secretaries of the Navy were “pro-slavery Southern politicians,” writes Canney, and their intentional neglect doomed the unit from the beginning.

As Canney concludes, “The result was an unusual situation where the zeal of individual vessel commanders often exceeded the expectations of the department, which was seemingly content with merely maintaining a presence on the slave coasts and thereby preventing embarrassing actions by the British against American seagoing commerce.”

Flying Death: The Vietnam Experience, HMM-164 Crew Chief by Samuel K. Beamon, Author House, Bloomington, IN, 2007, 216 pp., photos, $15, softcover.

Flying Death: The Vietnam Experience, HMM-164 Crew Chief by Samuel K. Beamon, Author House, Bloomington, IN, 2007, 216 pp., photos, $15, softcover.

Vietnam was America’s first truly integrated war. It would be the first time, on a large scale, that whites and blacks would fight alongside each other. During that turbulent period, the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum. Black groups, some advocating violence as well as peace, were formed. Some blacks were torn between their race and their perceived duty to their country.

Sam Beamon was such a man. Born and raised in Waterbury, Connecticut, he was fortunate to have loving parents who instilled pride, honor, and a sense of duty in him. When the Vietnam War heated up, Beamon enlisted in the Marine Corps. He was a crew chief aboard a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter in Helicopter Marine Medium (HMM)-164 during his 19 months in Vietnam and participated in numerous combat operations.

Being a member of a crew aboard a helicopter in Vietnam was not an easy task. The many hours of down time necessary to repair the complicated pieces of machinery and keep them airborne were taxing. More than that, there were the combat hours logged by the crews to support the ground troops in some of the most difficult terrain ever experienced by Americans during time of war.

Beamon had to fight another battle as well. He was one of the few blacks in his squadron and therefore felt that “he had something to prove.” And prove it he did. Beamon earned the Combat Action Ribbon, 16 Air Medals for participating in over 300 missions, and a host of other awards during his service. Most important, however, he earned the respect of his fellow Marines, and they formed a bond that still exists to this day.

Beamon returned home to continue to fight for equality. He quickly earned everyone’s respect and admiration. He served 28 years in the Waterbury Police Department, retiring as a lieutenant in the Youth Division. He was past commandant of the Brass City Detachment of the Marine Corps League and past commander of American Legion Post 135.

To this day, long after he stepped in the yellow footprints at Parris Island, South Carolina, Beamon still carries himself like a Marine. “Life is a learning experience, but it is also precious, fragile and very short,” he writes. “It should be cherished. Nobody can promise you tomorrow and whatever you decide to do in life—be the very best that you can be.”

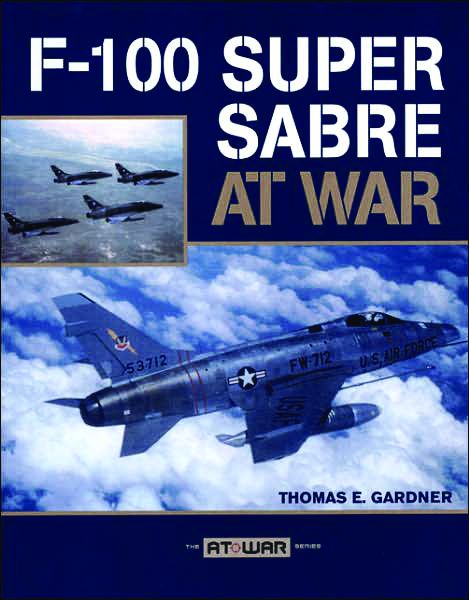

F-100 Super Sabre at War by Thomas E. Gardner, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 128 pp., photos, $19.95, softcover.

F-100 Super Sabre at War by Thomas E. Gardner, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 128 pp., photos, $19.95, softcover.

Zenith Press has just published their most recent entry in the “At War” series profiling various military units, equipment, and ships. The F-100 Super Sabre is an excellent choice for the series. It was the world’s first supersonic jet fighter, emerging on the scene just prior to the Soviet MiG-19. It broke speed and altitude records, and soon other planes followed in its wake: the F-102 Delta Dagger, F-104 Star Fighter, F-105 Thunderchief and F-160 Delta Dart.

Dubbed the “Hundert,” soon shortened to the “Hun,” the plane quickly earned the respect of the pilots who flew it. The author, Thomas Gardner, a mechanical engineer, has written a most comprehensive book on the aircraft. He examines every detail of the plane, including its engine, afterburner, landing gear, fuel system and cockpit. No part of the aircraft is left untouched. In addition, detailed drawings and illustrations plot the jet’s performance, and a chronological chart follows important dates in the design, manufacture, and final retirement of the world’s first jet fighter.

Last Flag Down: The Epic Journey of the Last Confederate Warship by John Baldwin and Ron Powers, Crown Publishers, New York, New York, 2007, 352 pp., maps, $25.95, hardcover.

Last Flag Down: The Epic Journey of the Last Confederate Warship by John Baldwin and Ron Powers, Crown Publishers, New York, New York, 2007, 352 pp., maps, $25.95, hardcover.

Sometimes historical gems are found in attics. Such was the case of one family, which discovered the diary of Lieutenant William Conway Whittle, the executive officer aboard the CSS Shenandoah, the last Confederate warship to lower her colors and surrender at the conclusion of the Civil War. John Baldwin, who co-authored the book, is a descendant of Whittle, and has studied his journal for years. His highly readable and exciting account of a ship at sea during time of war certainly brings to life an extraordinary tale of heroism and endurance.

Shenandoah was one of the most successful raiders built by the Confederacy. Although undermanned, far from their homes, and with no means of resupplying their stores on a regular basis, the vessel’s crew nonetheless performed admirably. Soon, Shenandoah had earned a well-deserved reputation for stalking and plundering Union ships. The vessel also did damage to Northern whaling ships as she sailed throughout the world. Whittle took great pleasure in disrupting northern commerce. He wrote, “It is to me a painful sight to see a fine vessel wantonly destroyed but I hope to witness an immense number of painful sights until our foolish and inhuman foes sue for peace.”

Although Shenandoah received word that the war had ended, she nevertheless persisted in her attacks on Union shipping well after hostilities had ended. Finally, on November 5, 1865, the Stars and Bars were lowered for the last time on Shenandoah. Most of the crew and officers could not return to their homes, however, because the United States considered them pirates and a price was on their heads. It would be years before many could return.

The story of Shenandoah and her indomibitable crew is a remarkable tale made even more fascinating by the journal of Lieutenant Whittle. His attention to details creates a larger-than-life picture of a remarkable voyage.

A Carrier at War: On Board the USS Kitty Hawk in the Iraq War by Richard F. Miller, Potomac Books, Dulles, Va., 2007, 243 pp., photos, maps, index, $17.95, softcover.

A Carrier at War: On Board the USS Kitty Hawk in the Iraq War by Richard F. Miller, Potomac Books, Dulles, Va., 2007, 243 pp., photos, maps, index, $17.95, softcover.

When author Richard Miller was ready to leave on his assignment to be imbedded with the crew of the USS Kitty Hawk, William Fowler, director of the Massachusetts Historical Society, reminded him to keep a diary. “Remember the debt you owe to those Civil War veterans upon whose diaries, letters, journals and memoirs you have feasted for all these years.” Fowler said.

Miller heeded Fowler’s suggestion, and as a result he has written a lively account of life aboard an aircraft carrier during the Iraq War. Although not a professional journalist, Miller embraced the assignment because he staunchly believes that “all wars share certain characteristics and that, if nothing else, the brain chemistry—the adrenaline, sleeplessness, aggression, guilt, and war’s strange seductiveness—transcends time.”

The author was allowed to roam the ship freely to talk to both officers and enlisted personnel alike to gain a well-rounded picture of what it is like to serve aboard an aircraft carrier during wartime. He was able to visit the hangar area, flight deck, engine room, and bridge to gather information. The result is both a fascinating book in its own right and a worthy tribute to those young men and women who served aboard Kitty Hawk during the Gulf War.

Founding Fighters: The Battlefield Leaders Who Made American Independence by Alan C. Cate, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, 2006, 250 pp., index, $49.95, hardcover.

Founding Fighters: The Battlefield Leaders Who Made American Independence by Alan C. Cate, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, 2006, 250 pp., index, $49.95, hardcover.

What were the military leaders like in the Revolutionary War? Certainly everyone knows George Washington and Benedict Arnold, but what of the lesser-known figures who played a prominent role in the American war of independence. Military historian Alan Cate examines 15 of the most dashing and interesting generals to emerge from that conflict.

Richard Montgomery was one such man. Originally serving in the British Army, Montgomery resigned his commission, moved to New York, and married into a prominent family. When hostilities erupted between England and her colonies, he offered his services to the Continental Army. Raising an army, he invaded Canada and joined forces with another well-known Revolutionary War personality, Benedict Arnold, to attack Quebec. While assaulting a blockhouse, Montgomery was killed, the attack fizzled, and the army was forced into full-blown retreat. Montgomery’s star might have shone bright, had the Canadian campaign been a success. As it was, his untimely death was a severe blow to the American cause.

Other interesting Revolutionary War figures such as Francis Marion, George Rogers Clark, Daniel Morgan, and Horatio Gates are also discussed in detail in the book. “These men made war,” writes Cates, “and in so doing helped make a nation.”

Eisenhower by John Wukovits, Palgrave MacMillan, New York, New York, 2006, 204 pp., photos, index, $21.95, hardcover.

Eisenhower by John Wukovits, Palgrave MacMillan, New York, New York, 2006, 204 pp., photos, index, $21.95, hardcover.

When John Eisenhower was asked to describe his famous father, General Dwight David Eisenhower, he said, “His greatest claim to brilliance rests on his utter relentlessness in the pursuit of his goal.” In this new addition to the Great General Series, author (and frequent Military Heritage contributor) John Wukovits delves deeply into the life of our 34th president. He concentrates on the five qualities Eisenhower possessed to achieve victory in World War II—focus, teamwork, empathy, media savvy, and devotion to duty.

These important traits, writes Wukovits, “helped guide and define Eisenhower’s life.” The Kansas native did not let his ego get in the way of performing his duty as a professional soldier. Unlike such fellow World War II generals as Douglas MacArthur and George S. Patton, Eisenhower put victory in Europe at the top of his to-do list—ahead of his own personal interests and drive for glory. While not lacking for ego, Eisenhower was able to subsume his personal goals in the service of the greater good, in this case the destruction of Adolf Hitler and his evil henchmen.

Eisenhower’s wife, Mamie, said of her husband after his death that he should be remembered because of “his honesty, integrity, and admiration for mankind.” Wukovits, while not writing a strict hagiography, agrees with the First Lady’s views.

Iraq and Back: Inside the War to Win the Peace by Colonel Kim Olson, USAF (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 211 pp., photos, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Iraq and Back: Inside the War to Win the Peace by Colonel Kim Olson, USAF (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2006, 211 pp., photos, index, $26.95, hardcover.

For anyone still needing a firsthand account of why the war in Iraq is failing horribly, Colonel Kim Olson’s engrossing book is the right choice. While on active duty, she assisted U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Jay Garner in his failed efforts to assist in rebuilding the war-ravaged country and setting up a coalition government. She also helped to set up humanitarian aid to the thousands of Iraqis left homeless after the initial wave of fighting had ended.

Instead of getting the nation on the path to recovery, however, Garner’s and Olson’s efforts to accomplish their mission failed miserably. Olson and her counterparts were repeatedly cautioned to disregard warnings about the growing insurgency, being told misleadingly by Bush administration figures that “the proclamations [were] crafted by ill-informed policy makers.”

Olson and her staff received regular death threats, and attempts were made on her life and on others in the delegation. In spite of this, she was adamant about traveling the countryside to see firsthand the effects of war on the civilian population. Especially compelling is her attempt to help refugees find missing family members in “Saddam’s killing fields.” Her poignant letter describing the squalid conditions in Umn Qasr, where the children ran out begging for water, is riveting.

All concerned Americans should read Olson’s book and discover for themselves the Bush administration’s terrible shortcomings in dealing with the aftermath of the Iraq invasion, written from the point of view of an eyewitness who was intimately involved in the process. It will definitely shock you.

Navy: An Illustrated History by Chester G. Hearn, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 192 pp., photos, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Navy: An Illustrated History by Chester G. Hearn, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 192 pp., photos, index, $29.95, hardcover.

For those readers looking for books dealing with the sea, then Navy: An Illustrated History is made to order. Author Charles Hearn traces the lineage of the U.S. Navy from its birth in 1775 up to the present day. The founding fathers could not have dreamed when they established the Continental Navy that it would evolve into the greatest seagoing power the world has ever seen. Included in its current arsenal are 276 active ships, over 4,000 aircraft of all types, and almost half a million military personnel.

Crammed with color and black-and-white photographs and detailed maps, Hearn’s book fully details the daring exploits of John Paul Jones and other leaders who fought Great Britain’s mighty flotilla. Hearn continues the story up to the Iraq War and a gives a glimpse into the Navy of the 21st century, where new technology is the guiding factor in determining America’s fleet and its newfound mission to combat terrorism around the world.

The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War by Clarissa W. Confer, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2007, 199 pp., photos, maps, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War by Clarissa W. Confer, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2007, 199 pp., photos, maps, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The American Civil War is often called “the brothers’ war.” Families were torn apart when taking either a Union or Confederate stance on the conflict. Nowhere was this felt more sharply than within the Cherokee nation, where the white man’s fighting left their homeland in ruins, overrun by regular forces from the Northern and Southern armies and also by roaming bands of merciless guerrillas and bushwhackers.

The author goes into minute detail on the horrible effects the Civil War had on the Cherokee, including policy-making within the tribe, the various military campaigns they participated in, the period after the war, and the devastating effects of Reconstruction on the Cherokee community. Perhaps the two greatest Cherokee leaders were John Ross and Stand Watie. Both are closely examined to demonstrate how the war created horrific upheaval in their personal lives and eventually left them destitute.

This is an intriguing account of a lightly examined aspect of America’s bloodiest conflict, as seen through the experiences of her earliest occupants. As Confer writes, “The American Civil War marked the beginning of the end of the independent Five Nations.” The Cherokee and other Indian tribes did not start the Civil War, but they certainly endured more than their share of suffering in it.

Once There Were Titans: Napoleon’s Generals and their Battles, 1800-1815 by Kevin F. Kiley, Greenhill Books, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 320 pp., maps, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Once There Were Titans: Napoleon’s Generals and their Battles, 1800-1815 by Kevin F. Kiley, Greenhill Books, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 320 pp., maps, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

“As a group they were arguably the greatest collection of military talent to ever serve one man,” writes Kevin Kiley in his new book Once There Were Titans. “Few commanders in military history were better served by their subordinates.”

Just who were these men who were willing to risk terrible weather, arduous military campaigns, and even death for their emperor? Kiley answers that question and more in his detailed account of Napoleon’s generals. He profiles 59 officers who played prominent roles under Napoleon, from the Battle of Marengo in 1800 to Ligny in 1815, men such as Alexandre de Senarmont, Jean Eble, Francois Teste, and the much lesser-known but nonetheless important Jean-Francois Boulart.

These generals, and many others like them, formed a loyal nucleus around their Corsican leader. There is no denying Napoleon’s military genius, but he also had a variety of dependable generals on whom he could rely for counsel. By doing so, the “Little Corporal” led his forces to numerous victories—even if he usually claimed all the credit for himself.

Secret and Dangerous: Night of the Son Tay Raid by William A. Guenon, Jr., WagonWings Press, Ashland, MA, 2007, 140 pp., maps, photos, $15.00, softcover.

Secret and Dangerous: Night of the Son Tay Raid by William A. Guenon, Jr., WagonWings Press, Ashland, MA, 2007, 140 pp., maps, photos, $15.00, softcover.

One of the most daring raids ever conducted behind enemy lines was the incursion into North Vietnam by Special Forces soldiers to liberate prisoners from the Son Tay prison camp. Now there is finally a fascinating firsthand account by an Air Force pilot who flew the lead aircraft, dubbed Cherry One, on the mission. Bill Guenon, Jr., gives the reader a close look at the preparation and execution of the raid deep into enemy territory. He also returned to Vietnam many years after the action to visit Son Tay and share his vivid memories of that fateful night with his former enemies.

Although the raid did not free any prisoners (they had been moved by the North Vietnamese some months prior), it did achieve some beneficial results for those who were imprisoned. “Within three-four days of ‘Banana One’s’ planned crash landing in the middle of the compound, all the American POWs were joined together in Hanoi for the first time,” wrote Brig. Gen. Jon A. Reynolds, USAF (Ret.), a former Son Tay inmate, in his introduction to Guenon’s book. “Several men who had been in solitary confinement for over four years found themselves with roommates for the first time. Morale soared. The Vietnamese were visibly shaken. Even though not a man was rescued, the raid was still the best thing that ever happened to us. God Bless the Raiders.”

Future Weapons by Kevin Dockery, Berkley Publishing Group, New York, New York, 2007, 326 pp., photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Future Weapons by Kevin Dockery, Berkley Publishing Group, New York, New York, 2007, 326 pp., photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The evolution of military firearms has captivated people for years. But what of the future weapons that soldiers will carry into battle? Will they be able to withstand the rigors of combat? Historian, author, and armorer Kevin Dockery has written a book that examines the sidearms, rifles, and rocket launchers that will accompany troops into the field when they deploy in future conflicts.

Each weapon has a list of data that includes caliber, length, load, muzzle velocity, sights, and weight both loaded and empty. Another interesting topic discussed is the probable use of robotic soldiers and the likelihood of waging war in both space and cyberspace. “On these pages are the weapons that are being built today and in the years to come,” says Dockery. “These are not imaginary pieces of hardware. They are weapons that will be used to fight the immediate conflicts of today and the wars of tomorrow.”

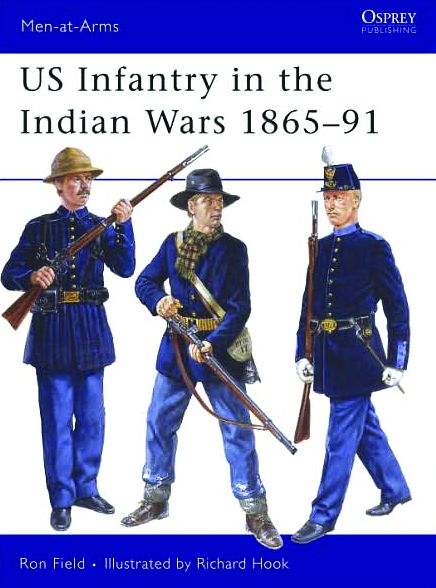

US Infantry in the Indian Wars 1865-91 by Ron Field, Osprey Publishing, New York, New York, 2007, 48 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $15.95, softcover.

US Infantry in the Indian Wars 1865-91 by Ron Field, Osprey Publishing, New York, New York, 2007, 48 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $15.95, softcover.

Whenever the Indian campaigns in the West are discussed, the infantry is rarely mentioned. Most Americans believe that the colorful battles and skirmishes fought on the Great Plains were strictly cavalry affairs and that the foot soldier sat out the bloody engagements in relative safety inside a fort.

Nothing could be further from the truth. United States infantry units, referred to as “Walk-a-Heaps” by Lakota Chief Crazy Horse, endured arduous marches in tracking down hostile Indians. From 1866 until 1891, the U.S. Infantry took part in 221 battles, sometimes with, other times without the cavalry. The Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest award, was presented to nine officers and 61 enlisted men during that period.

As with all Osprey publications, the book is richly illustrated with color paintings and rare photographs depicting the uniforms and sidearms and rifles carried by the soldiers. The publisher has offered another worthy contribution to the Men-at-Arms series that readers will find most interesting.

Lt. Bill Farrow: Doolittle Raider by John Chandler Griffin, Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, LA, 2007, 269 pp., photos, index, 424.95, hardcover.

Lt. Bill Farrow: Doolittle Raider by John Chandler Griffin, Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, LA, 2007, 269 pp., photos, index, 424.95, hardcover.

On April 18, 1942, 16 B-25B Mitchell bombers took off from the deck of the USS Hornet, the first time that Army Air Corps planes were flown from a U.S. Navy carrier during wartime. The raid was a huge morale booster in the wake of the recent surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese, when the United States sustained thousands of casualties.

One individual who participated in the famous attack was Lieutenant William Glover Farrow, a native of Darlington, South Carolina. Unfortunately, Farrow was captured and executed along with Lieutenant Dean Hallmark and Corporal Harold Spatz on October 15, 1942, after being tried by a Japanese kangaroo court. Farrow’s loved ones never learned his fate until after the war, when his letters and an urn containing his cremated remains were recovered.

The author has done meticulous research to recreate the life of a brave American by interviewing family members and reading his letters. It is a fitting tribute to a courageous group of Americans who flew their planes deep into Japanese territory to demonstrate Japan’s vulnerability from the air, and in doing so became part of American military history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments