Correction

In our June 2002 story about Napoleon’s campaign in Italy, we misidentified the credit for the illustration on page 33. The watercolor art of French soldiers in Italy was painted by Johann Baptiste Seele, an artist who accompanied Napoleon’s army. The credit should have read: James L. Kochan Fine Art & Antiques, Shepherdstown, WV.

Distinguished Writing Award

Dear Mr. Stoddard:

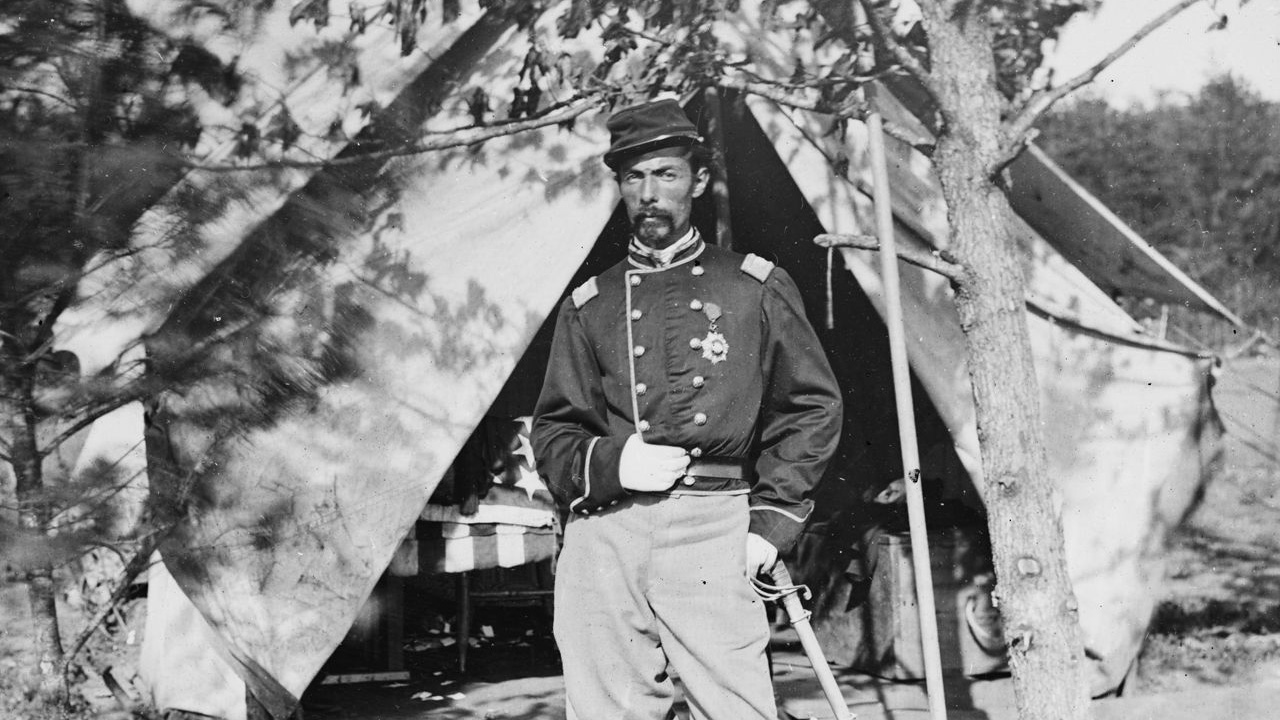

Thank you for your kind letter informing me that the article on the Civil War Battle of Allatoona, Georgia, entitled “Hold Allatoona!” (August 2002) has been selected as one of the finalists for the Army Historical Foundation’s 2002 Distinguished Writing Award.

I am pleased, both for myself and for Military Heritage, that the article was chosen, and will, of course, hope for a favorable outcome. I thank you most sincerely for informing me of this and look forward to hearing about the outcome of the judging.

Yours truly,

William B. Allmon

Jefferson City, Missouri

General Walton Walker

Dear Editor:

In the April 2003 issue of Military Heritage on page 26 the author states that General Walker, then a colonel in WWI, was awarded the Silver Star, second only to the Medal of Honor. He apparently forgot about the DSC, Distinguished Service Cross, which is next to the Medal of Honor in rank of medals.

As a WWII infantry veteran, I enjoy your magazine.

James G. Graff, President

35th Division Association

Middletown, Illinois

Dear Editor:

I read Blaine Taylor’s article on General Walton Walker with keen interest, since I have written about the man a number of times. His is a fair treatment of the general, but some of his remarks concerning other matters are way off the mark.

He writes that “a wholesale rout began.” Although the North Korean attack was generally successful at the outset, they suffered significant setbacks by the Republic of Korea (ROK) 6th Division, taking on two enemy divisions and inflicting very heavy casualties on both. The ROK 1st Division, although heavily engaged, fought hard and with great determination. On the east coast, ROK artillery destroyed two North Korean boats and forced the withdrawal of a North Korean naval force in the area. In spite of all this, the North Koreans pushed through, rupturing the ROK defenses along the 38th Parallel. The ROKs then resorted to a series of delaying actions. U.S. ground forces fought their first battle on July 5, 1950, near Osan. It was about 500 Americans against over 2,000 enemy infantry and some 30 tanks. The Americans delayed the enemy for seven hours.

Next, he writes that the GIs “hauled ass, abandoning their weapons as they did so.” The battles of the ROK army and the American action on July 5 were part of a whole series of delaying actions fought by the ROKs and U.S. troops along roads and rail lines leading south. President Syngman Rhee’s wife did not know what she was talking about in her July 14, 1950, letter. The mission of both the ROK and American Eighth Army at the time was to delay the enemy, not fight him to the death on every hilltop. What people do not realize is that we had insufficient troops in Korea at the time to man and defend a defensive line. Most battles were between an isolated battalion against elements of an enemy division. There were no friendly troops on the flanks or in the rear to help. In short, we fought these battle alone.

It is true that the U.S. 24th Infantry Division, the first American division committed to Korea, lost great amounts of weapons and equipment, but that command had to be committed to battle piecemeal, and by piecemeal, it was destroyed by enemy forces that far outnumbered it.There was no rout and no wholesale abandonment of weapons and equipment in the context that Taylor implies.

Next, Taylor implies that MacArthur conceived the idea of the Pusan Perimeter. He may have decided that the ROK and American forces would have to make a stand somewhere, but it was Walker who chose the Naktong upon which to build the western face of what became known as the Pusan Perimeter.

Walker’s famous “Stand or Die” edict, issued at the 25th Division command post, was made to molify MacArthur. On July 26, 1950, MacArthur had been informed falsely by his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, that Walker planned to move his command post from Taegu down to the port of Pusan. Based on that, MacArthur flew to Korea, and in a condescending and humiliating diatribe told Walker that there would be no pulling back to Pusan. Walker had no such intention. All he wanted to do was send an irreplaceable communications system and certain administrative elements of his headquarters back to the vicinity of Pusan. The latter move was to clear his road net of unnecessary traffic so that he could more speedily move troops around to meet enemy attacks. The so-called Pusan Perimeter did not begin to take shape until the first days of August 1950.

Taylor wrongly states that the 25th Division commander was Maj. Gen. William F. Dean. Dean commanded the 24th Division, but was missing in action as of July 20 at Taejon. The 25th was commanded by Maj. Gen. William B. Kean.

These errors severely mar an otherwise very good summary of General Walker’s career, and are insulting, at least, to the men who fought and died during those first months of the Korean War. Those were the bloodiest months of the entire war.

I was there as a rifle platoon leader in Co. B, 27th Infantry Regiment. About 10 years ago Turner Publishing Co. published my history of those first months of the war. It is entitled Fighting on the Brink: Defense of the Pusan Perimeter. The book is not a personal history, but one that encompasses the entire campaign and the battles leading up to the formation of the Perimeter. It is recognized by men who were there, as well as eminent historians, as the most complete and accurate account of those first days of the Korean War.

Uzal W. Ent Brig. Gen., PNG, Ret.

Camp Hill, Pennsylvania

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments