By Fred T. Martin

Winston Churchill called it, “An immense laborious task, unlikely to be completed until the need for it has passed.”

Churchill was referring to the construction of the Ledo Road out of the Assam province at the eastern extremity of India, to connect with the Burma Road, the ancient high-mountain pathway to the interior of China. Allied air bases there needed massive shipments of supplies and fuel for the B-29s attacking Japan.

Twenty thousand engineers and 35,000 natives labored for two years to open the Ledo Road. When completed, it took truck caravans over a month to cross the 800 miles to China, over grades up to 17 percent, and under Japanese air attacks. Churchill wasn’t far off—the road was done less than a year from the war’s end.

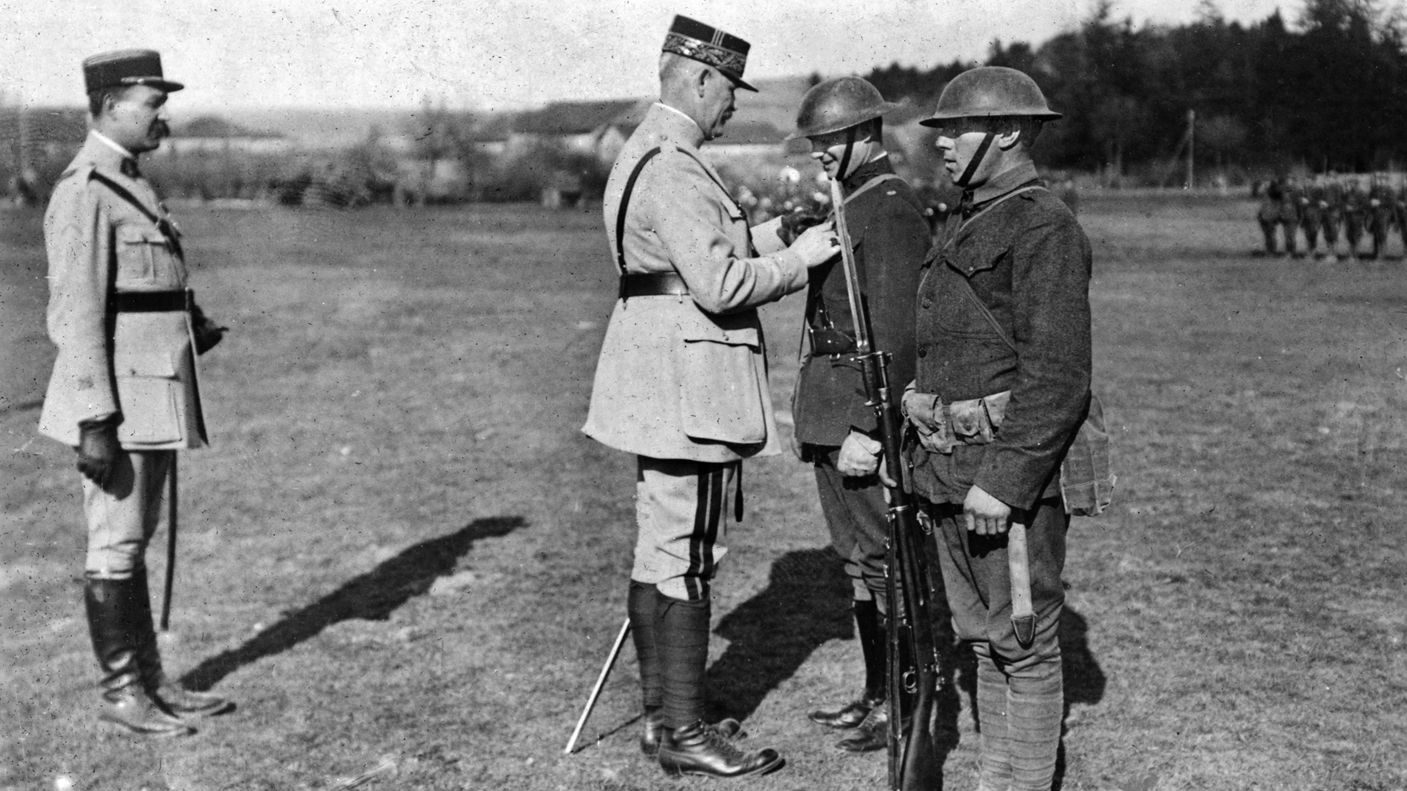

This project would not have been needed but for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which thrust the United States into the war. With Japan swiftly gobbling up islands and nations in and along the Pacific Rim—including China—there was suddenly a need for America’s unprecedented ability to achieve the seemingly impossible.

Late into that grim December 1941, Japan was poised to move next against India. If they cut off access to the Burma Road from the seaport of Rangoon, the Allies could not supply China. On Christmas Eve 1941, Japan attacked British Burma and seized Rangoon.

The Asian theater turned to chaos. Churchill’s eastern British empire was collapsing. An American-British-Dutch command was hastily formed to defend the region. American commanders immediately demanded bomber air bases in China and the strengthening of Chinese resistance forces. China was made an ally and General Chiang Kai Shek became Allied Supreme Commander for China.

With many Pacific islands, and now Rangoon, under Japanese control, these bases could only be supplied from eastern India. So, with the Burma Road cut off from the sea, the massive Ledo Road project was required to connect the Assam Valley to the Burma Road in the north.

By April 1942, the truck caravans could not meet the enormous demands of the China bases. Ground transport on the Ledo Road was not practical. The transport problem would be solved only by airlift flying over the highest terrain on Earth. The “Hump” airlift operation was thus created.

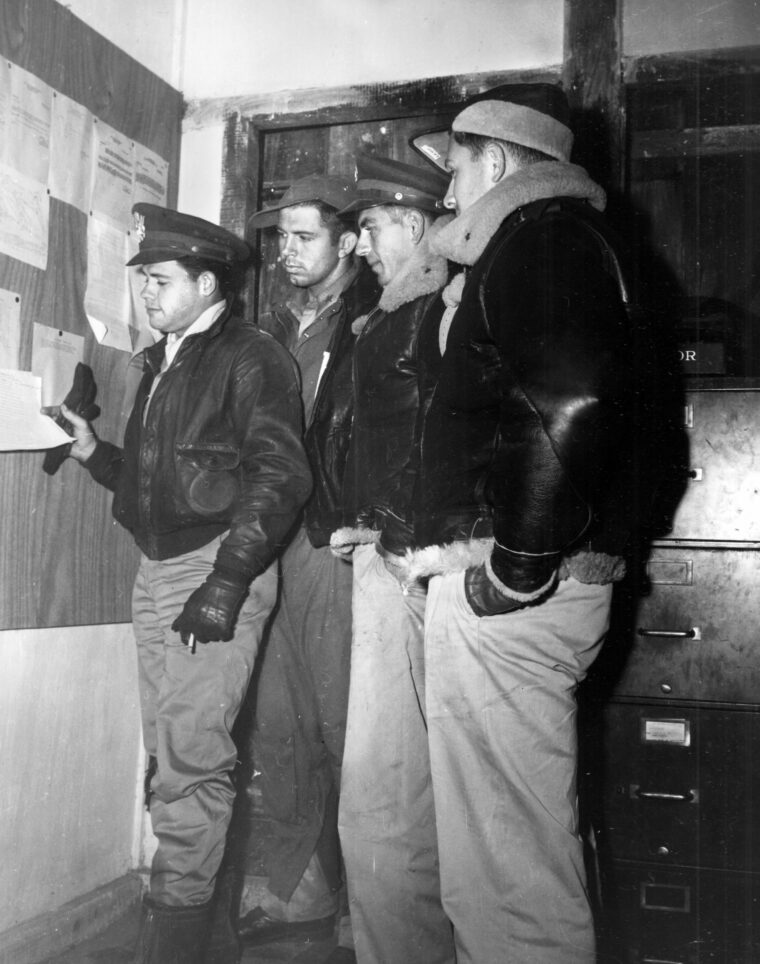

The India-China Airlift, or Himalayan Hump Operation, was the highest-loss, highest-risk air transport mission of World War II. Pioneering aviators carried thousands of tons of gasoline and materiel over the world’s tallest mountains to supply the bases deep in the interior of China to support early bombing missions on Japan.

Flight operations in alpine conditions at this altitude had never been attempted, much less on a year-round, all-weather basis. Winds aloft were often measured at over 250 miles per hour, and downdrafts were encountered of over 3,000 feet per minute. Average terrain levels on some routes were over 20,000 feet above sea level, and airfields were carved out of forests. Navigation aids were scarce. Add to that the intensely hazardous payload of thousands of gallons of gasoline carried on many of these flights.

As operations accelerated, over 10,000 tons were carried across the Hump per month. In all, 650,000 tons were delivered over the Himalayas. It is estimated that, on average, a flight crewmember was lost for every 500 tons. More than 1,300 aircrew and 600 aircraft were lost due to weather, malfunctions, and Japanese fighters. There were nearly 1,200 bailouts over the Hump; 345 men were never found and were listed as missing in action.

General Claire Chenault, the region’s air commander, said that only men of special caliber could live up to the demands of the Hump. They were the swashbuckling pilots of the India-China wing.

The Hump operation completed the longest materiel supply line in the world. After the 12,000-mile ocean voyage from the U.S. to Karachi or Bombay (Mumbai), shipments traveled 1,500 miles on India’s dilapidated main rails to connect with the ancient Bengal-to-Assam rail line.

That route, called “The Toonerville Trolley” (from a popular newspaper cartoon feature of the day) by American personnel, had been built to haul tea, and changed gauges three times on the way to a barge crossing at the Brahmaputra River. Then, as one commander put it, “every bean and bullet” had to be flown from bases in Assam over into China. General Chennault estimated that for every ton of bombs delivered to China, 18 tons of materiel had to be flown over the Hump.

The air route to China rose out of the Brahmaputra River valley from air bases at about 200 feet above sea level, out to the northeast over the 10,000-foot Naga Hills (named for the head-hunting tribe that lived there). It then crossed the gorges of the Irrawaddy, Salween, and Mekong Rivers, and on up to the backbone of the Hump—the Santsung Ranges of eastern Sichuan and Tibet.

Pilots referred to the route as “the aluminum trail” because of the number of airplanes lost along it. (Clayton Kuhles of MIARecoveries.org conducts heroic modern expeditions into the high mountains to locate wreckages of Hump aircraft. They have found 27 missing aircraft and 279 personnel, some listed for decades as missing in action.)

Hump crews flew pioneering aviation routes over regions never before seen by human eyes. My father, Frank D. Martin, often flew alongside Minya Konka, the highest peak in eastern Sichuan, standing 1,000 miles east of any mountain of comparable height.

This area was long a blank spot on the map until the 1930s, when a National Geographic expedition estimated that Minya Konka might be higher than Everest—no one knew. Fewer than 60 alpinists have climbed it and 16 have died in the attempt.

Many histories often overlook the heart and soul of the human being who experienced war. So, for my father and mother and many other veterans I have studied, the personal story of war is where the core meaning of history is best revealed.

I first heard of the Hump Operation when I was a young man fishing with my father on a remote Canadian lake. Dad had never told many war stories, but that day, between hooking walleyes, he spontaneously, and uncharacteristically, began telling me of aerial gasoline tanker crashes at his World War II air base in India.

He was suddenly recalling, in obvious anguish, how he had to watch helplessly as friends perished before his eyes, the flailing of those men’s bodies as they were consumed by the flames and the pouring black smoke, and how they slumped over, still buckled in their seats as the cockpit exploded and he was powerless to rescue them.

I was stunned and awkwardly turned away to the tackle box in silence. But then I turned back from the fishing gear and promised him that, one day, I would write his biography.

Seven years after his passing, remembering my promise, I dug into his scrapbook records. Yet, the clippings in those shoeboxes were entirely from his post-war years with the Cessna Aircraft Company. He became Vice President of Marketing. I have told that story in another book, Reminiscences Over Old Airplanes.

His lengthy autobiographical notes offered little about the war. What he wrote about all his World War II experiences—everything I write about in my book, Among Stars Above the Storm, and all that I tell here—was a total of six sentences.

After the war, my father was like many of his World War II contemporaries, eager to return to a new life away from the war they were weary of. When they might have been ready to talk about it, there were few who had not been to war who could understand. Also, among veterans, there was an ethic against tale-telling braggadocio. Most believed that the only heroes of any merit, and the only ones who deserved to have their stories told were the ones who did not return.

During my boyhood time with him, my father did recount a few stories that provided key recollections for my book, but he was too busy living in the post-war world as an explorer, aviator, and businessman, to look back at the past, and he spoke very little about the war. So, this story would have been lost.

But several years later came a blessing within a life tragedy. I had to move my brilliant, high-achieving mother into an Alzheimer’s-care facility. After the war, my mother, Sarah E. Martin, had her own illustrious career in the Federal Government, becoming Secretary to the Director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

When she moved to the care home, I cleaned out her house, discovering her most secret possessions. Deep in a lower drawer, hidden beneath old clothing, were loose-leaf binders of 211 letters my father had written to her during his nine months in India. That was nearly a letter a day, each one lengthy, hand-penned from a jungle hut or from a freezing cockpit high above the most remote mountain reaches of the Earth.

My parents divorced when I was six, so these letters, which revealed a love story of a grandeur that reflects the world war it was set within, were of great value to me. Here, I had the secret window on their war-parted love affair. The letters, when correlated with the pilot log books, allowed me to assemble the details of event-filled flights between India and China, and daily life in India.

They reveal my father’s intensifying stress and emotional state as his time in India wore on. Mother also saved notebooks of his Army orders and teletype war reports from all over the world that had come into her office where she worked, remarkably, as Secretary to the Commander, New Castle Army Air Base, in Wilmington, Delaware.

This was the base of departure for my father’s trans-Atlantic flights delivering B-17 bombers to the Eighth Air Force in Europe, and from where he departed on his long flight around the world to India; to the Hump. In all the intervening years, she had never revealed that she had these letters. Dad never mentioned them and had likely assumed Mother had not kept them after their divorce.

Finally, in 2007, I opened old cigar boxes of 3×5 black-and-white photographs, curled, faded, and crumbling, along with a brown case of carefully labeled color Kodachrome slides. At that time, these photos were over 65 years old! In their original deteriorating condition, they had never much caught the family’s eye. Yet after computer restoration and enlargement, the composition and quality of many of the photographs was astonishing.

Many revealed that Dad had quite a knack for composition, along with a compassionate eye for his subjects. And these were subjects of historic proportion. I had discovered another treasure that illumined the first, and brought the letters from India vividly alive.

My father arrived in India on April 30, 1944. He had been assigned to deliver a twin-engine C-47 from Wilmington, Delaware to Sookerating, India. It is illustrative of the enormity of operations required to move thousands of U.S. aircraft around the world during the war that Dad’s flight to India took 22 days and 95-1/2 flight hours. The trip proceeded across the Caribbean, down the coast of Brazil, across the Atlantic to Ascension Island, across North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and across the breadth of India.

Shortly after he arrived, Dad went to watch a movie at the air base outdoor theater. He saw a familiar face that turned out to be his cousin, Frank Osborne, a boyhood companion from the mountains of southwest Virginia. Neither man knew the other was in the war. Osborne was a P-40 fighter pilot passing through on his way home from China. His P-40 squadron had been defending the China bases at the other end of the Burma Road as part of General Chennault’s famous Flying Tigers.

Flights over The Hump began with the twin-engine C-47, the military variant of the Douglas DC-3, but there would be a number of aircraft types involved in the operation. The larger twin-engine C-46 was famous over the Hump, along with the four-engine C-54. My father flew the transport derivatives of the four-engine B-24 bomber platform, the C-87 and C-109.

My study has focused on technical details of those airplanes. The C-87 was hastily developed in early 1942 as a heavy cargo and personnel transport with longer range and better high-altitude performance than the C-46 or C-47. It was converted from the B-24 bomber by deleting gun turrets and other armament, and the installation of a strengthened cargo floor running through the bomb bay. A door was added on the port side, and windows were fitted along the sides of the fuselage. The C-87 could carry up to 25 passengers or 12,000 lbs. of cargo.

With war production shortages, many C-87’s were fitted with turbo superchargers with lower boost pressure than those fitted to B-24s destined for combat use, so ceiling and climb rate were adversely affected. Yet, over the Hump, the C-87 was the only readily available American transport with adequate high-altitude performance to fly this route with a large cargo load.

But the C-87 was plagued by numerous problems. Ernest K. Gann, a C-87 pilot who hated the airplane, wrote in his book, Fate Is the Hunter: “They were an evil bastard contraption, nothing like the relatively efficient B-24 except in appearance.”

The plane had a clumsy flight-control layout, frequent engine problems, hydraulic leaks, and a disconcerting tendency to lose electrical power in the cockpit during takeoff and landing. The C-87 did not climb well when heavily loaded, a dangerous characteristic when flying out of the unimproved, rain-soaked airfields of India and China. Many crashed soon after takeoff.

Gann himself had a near-collision with the Taj Mahal in a C-87 in a takeoff mishap. He wrote, “The assembly of parts known collectively as a C-87 would never replace an airplane.” The aircraft’s auxiliary fuel tanks were linked by improvised and often leaky fuel lines that crisscrossed the crew compartment, choking crews with noxious gasoline fumes and creating an explosion hazard.

The C-87 also had a tendency to enter an uncontrollable stall or spin in the event of inflight airframe icing, a frequent occurrence over the Himalayas. Gann said the C-87 “could not carry enough ice to chill a highball.”

The C-87 also had center-of-gravity problems due to improper cargo loading. Unlike other cargo transports designed from the start with a contiguous cargo compartment and safety margin for fore and aft loading variations, the bomb racks and bomb bays in the B-24 design were fixed in position, greatly limiting the aircraft’s ability to tolerate improper loading.

This problem was made worse by the failure of the Air Transport Command to instruct loadmasters in the C-87’s peculiarities. The C-87’s roots as a bomber were also considered the cause of frequently collapsing nose gear. Its strength was adequate for a B-24 that dropped its payload in flight before landing, but it was a weak design for C-87s making repeated hard landings on rugged unimproved airstrips while heavily loaded.

Another much-hated plane was the C-109—a dedicated fuel transport version of the B-24 platform. It is considered the first U.S. aerial tanker. It carried 2,900 U.S. gallons of aviation fuel in several internal fuel tanks in addition to the 2,800 gallons in the wing tanks. These planes burned three gallons of fuel for every gallon delivered.

The C-109 was even more unpopular with its crews than the C-87. The aircraft had unstable flight characteristics with all storage tanks filled, and proved very difficult to land fully loaded. At least 80 C-109s were lost in flying the Hump airlift. A crash landing of a loaded C-109 inevitably resulted in an explosion and crew fatalities.

Indeed, at the Tezpur base, aircraft were crashing regularly on takeoff in horrific fireballs. Flights were frequently lost enroute to Japanese attackers and for reasons unknown. In early June, 1944, the ship of the chief pilot was reported missing, then another colleague crashed.

My father wrote to Mother, “He’s in the hospital with broken bones. Some of his crew were not so fortunate. Our safety record here has just gone flop the last few days. Two crews lost, one definitely all killed, the other missing. Hainey still in the hospital in China, Bill Schonessee is OK except for missing most of his teeth.

“Sure wish the enemy would just fold up, but I can’t see it for a mighty long time. To listen to Jap broadcasts from Shanghai you would think that they are going to win.”

The India-China airlift was a non-combat operation, and that imparted an added sense of tragedy to the frequent crashes. If an airline or any transport operation suffered such multiple crashes each week, with many right at the airport, then what pilot would continue flying—and what passenger or crew member would ever board the aircraft?

On takeoff in a loaded tanker, the airplane is sluggish, barely airborne, balanced on a tight wire of airspeed wherein single mile-per-hour increments make all the difference between a climb beyond hill or trees, or mushing back to the ground. A backfiring engine, a downdraft, a payload slightly off center of gravity, a momentary lapse in concentration—these were only some of the factors that could bring down the airplane and its 6,000-gallon load of gasoline.

Early in 1944, the commander of operations issued a directive that no flights were to be canceled or delayed because of weather. This order was widely referred to as the “There will no longer be weather” decree, and pilots quipped that if the weather could be thus ordered away, perhaps a similar order could be issued to the Japs. Weather had closed the route to China half the time.

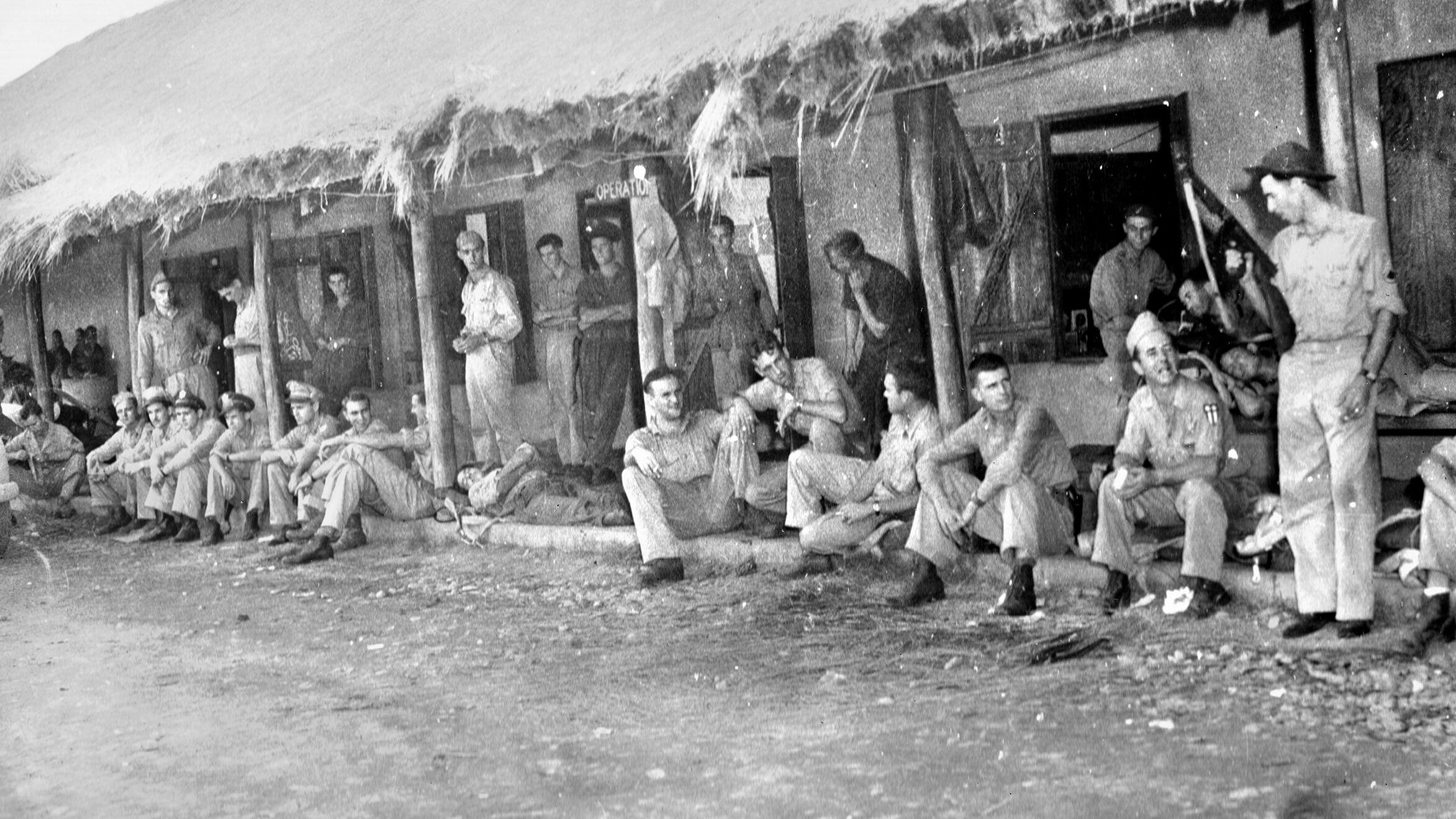

Air bases on both sides of the Hump were built employing native labor. Entire families worked on India bases, while in China, rock crushers, mostly women, broke gravel using hammers, then carried it to the airstrip in baskets on their heads.

Up to 100,000 coolies worked on each China base. Construction equipment was scarce. Ox carts were used to haul rock. Hand-drawn rollers pulled by 100 coolies or more flattened the field. The result was a bumpy airfield about 6,000 feet in length.

My father’s experiences flying the Hump were similar to most crews in the operation. Comparing the dates of his letters home to those of his pilot flight logs best illustrates the arduous, unrelenting pace of flight operations.

Dad’s August 14 trip was typical: a 10.5-hour round robin to Chengtu, back over to Sookerating, and down to Tezpur. Then he was called out at 4 a.m. for another flight—a seven-hour, 40-minute round trip back to Chengtu.

He wrote Mother that night: “Now it’s after 10 and I just got through talking to Buddy and other guests. I am so tired and dopey that I really don’t know what I am doing half the time. It sure gets dark out over that thousand miles of stone at night. That is, until we hit the roughest weather yet last night, and the storms lit things up like day. We were barely getting over the top of the thunderclouds, and when we broke clear, we were flying among stars above the storm.” That’s the passage that gave the title for my book.

The pace of operations intensified. On September 3rd there was a 10.5 hour trip to and from Chengtu. The next day, the flight was nine hours, 45 minutes to and from Pengshan. The next day: 11 hours to Kwanghan, then, Kwanghan again on both the next two days.

There was no time to worry over the deaths of other pilots. The most imminent enemy was crushing fatigue. A single trip over the Himalayas was a flight of expeditionary proportion at this time in aviation history.

Two days later, Dad flew his 40th trip over the Hump to Pengshan. The next day he flew back to Pengshan and Sookerating. The next day, 10-and-a-half hours to Kwanghan, then another round trip to Kwanghan on the same day! That was an unimaginable 22 hours of flying the Himalayas in one 24-hour period, after one night off in 10 consecutive days of such flights.

The next day, Dad wrote Mother a letter about those 22 hours of flying: “Dearest Sally [his name for her]: Had a long trip yesterday and didn’t get to bed until 2 a.m. today. Flew 35 Chinese back to India last night and landed them at another base. So was late getting home.”

These were Chinese Nationalist soldiers under Chiang Kai-shek. Most had no boots, only straw sandals. The bedding issued to some units was one blanket per five soldiers, and pay was so low even officers could not afford any more food than rice. They were plagued by dysentery, smallpox, and typhus to such a degree that some units had 40 percent losses without entering combat.

Dad wrote of his passengers that night: “You have never smelt a real odor.” Because of censoring, what Dad could not mention in this letter is that several of these Chinese soldiers had died in his airplane. It had been a six-hour flight over the mountains with no oxygen at sub-zero temperature. Years later, that day while we were fishing together, Dad wondered if the families of the dead ever found out what had happened to them, or if the soldiers who had survived the flight had ever found their way back home across the Himalayas.

A few days later he wrote Mother, “I need a good cry tonight but just can’t. One of our finest friends; one of the best fellows I have met, was killed last night. His ship crashed and burned right after takeoff.”

Two days later, another ship crashed on takeoff killing three in the crew, with one badly hurt survivor. “Can’t tell you how I feel right now,” Dad wrote. “If I only had you to talk with sometimes, I could stand things so much better.” The funeral for their friend was the next day and then the survivor of this latest crash died in the morning. It had been the young man’s first Hump mission.

After another flight to Kwanghan, Dad wrote, “Did you hear?! We bombed Japan yesterday! It was B-29s from our theater!” This is what the massive effort was all about: hauling all this gasoline over the mountains.

He went on, “I can’t answer your question about where the B-29s are. It’s secret. No one but the Japs and a couple million other people know where they’re based. They sure are big, though!” He had no idea at that moment that he would be a B-29 commander in 10 months.

These B-29 missions through Kwanghan defy belief. Flying from Calcutta over the Hump, they landed in Kwanghan to refuel and load ordnance. Then, the incredible round trip to bomb Japan, back to refuel in Kwanghan, and then return to Calcutta, where the bombers were safer from Japanese attack.

On October 7, my father and his co-pilot took off toward China. Heading into the mountains, they encountered turbulence so severe that a man’s head would be smashed on the ceiling of the cockpit if not for the shoulder harnesses holding them to their seats.

A fuel barrel burst and 55 gallons of gasoline spilled out on the deck. This was the era of many arcing electric relays and red-glowing vacuum-tube radios. The co-pilot began frantically tugging on his harness releases wanting to get up and get his chute on. He preferred bailing out in a thunderstorm over the Himalayas to dying in a fireball.

Releasing the shoulder harness would have been enough to kill him. Eventually, they broke out in the clear and set a return course for Tezpur. They shut down all the electrics they could, and planned their landing of the heavily loaded freighter. The landing gear could be cranked down by hand, but they were going to have to use the electric landing flaps to stop the airplane on the jungle strip, and there would likely be a small electric arc when they hit the switch.

Dad winced as he reached for the flap switch, he hesitated, and then lowered the flaps. He wrote, “There was no reason the aircraft didn’t explode.” For security reasons, pilots included few details of flights in their logbooks. Dad’s log entry for this flight has the rather understated notation: “Returned with leaky gas drum.”

Two nights later, Dad was supposed to fly to China, but another ship crashed on the field and he went to visit the hospital. “There were five aboard,” he wrote Mother, “all real badly hurt. I gave a transfusion to the pilot, so I can’t fly again for another day. He died a few minutes later, which doesn’t speak too well for my blood, but he was so badly mangled and broken, it’s a miracle he lived even a minute. Another one is being operated on for multiple skull fractures and chances aren’t too good.

“But the doctors have pretty high hopes for the other three. Somehow this crash doesn’t bother me a bit, but the last one I told you about had me pretty upset. Several ships have just disappeared in route, the Japs have gotten a couple, and with all the crashes going on, you get so that it’s just another one.”

The next night Dad mailed his letter and went out for another flight. He had a new co-pilot he had known on the North Atlantic runs. It was the fellow’s first trip over the Hump. It was foggy that night, so visibility was obscured as they held short in the rumbling tanker waiting for clearance. Dad took the runway and accelerated. Halfway down, another tanker came looming out of the dark fog head-on.

The other pilot was taxiing, and he kicked his rudder pedal hard and turned his ship off the runway into a ditch that ran alongside. That ship’s nosewheel dropped into the ditch and the big double rudders cantilevered up in front of Dad’s accelerating airplane. There was no time to react, and no space to maneuver in.

His ship had not reached liftoff speed, but Dad pulled back hard on the control column and the gasoline-laden C-109 wavered off the ground, with one of the main landing gear striking a rudder on the other aircraft. Dad’s ship yawed wildly, but somehow remained in flight and clawed out over the trees.

After gaining a stable flight attitude, they had to make a decision. The landing gear must have been bent or broken, they reasoned. Surely the tire must have been blown out. The co-pilot went back to look out a window; he tried to assess damage with a flashlight. Nothing was apparent, but it was impossible to know. Should they return for landing in Tezpur overloaded with gasoline, or try retracting the gear and burn off their wing tanks flying to China, where they might not be able to lower the gear, but would be lighter for landing?

Their duty was to deliver the fuel to China. They retracted the gear and had a very anxious flight to Kwanghan. Fortunately, the landing there was without incident. A hearing was later convened about this runway accident. The field controller that night charged that Dad had taken the runway without a clearance. Dad’s testimony was simply honest: “I was so tired and sleepy, I really can’t tell you if I had a clearance or not.”

Two other pilots listening on the field frequency that night testified they had heard the clearance. Perhaps they heard it, perhaps they were covering for a colleague. Either way, all knew it was senseless to court-marshal a desperately needed pilot. The hearing was closed.

The next night after this harrowing flight, Dad went to relax at the outdoor movie before his next departure scheduled for the early morning. The movie was Shine On Harvest Moon, starring Ann Sheridan and Dennis Morgan, but it was cut short when there was an explosion and the sky lit up like day. Another tanker had crashed a mile after takeoff, not as fortunate as Dad had been the night before.

“It all seems so insane and useless to me,” he wrote Mother. “It isn’t the Hump that’s dangerous, but the rushing and assigning of unqualified personnel.” He returned to his basha (a hut typically made of bamboo and grass) late that night from the crash scene. The chaplain and several others were on the porch conversing in low tones. They gave him more bad news. The young pilot who lived next door was missing. They found the wreckage in China the next morning.

Dad wrote, “Four more dead—all of them. Penny-wise and pound foolish the way the Army does things, and it sure makes you sick.

“We have a cute little puppy now named ‘Ding How.’ The young man who was killed last night brought her back from China and raised her on an eye dropper. Now that he’s gone, she seems to have adopted us.”

The central story my father would have wanted told was about people. He actually took few photos and wrote little about airplanes and operations. His real story is that he fell in love with the people of India, and most of what he wrote was about his growing fondness for the people of Assam.

He became close to one family in particular and spoke of the most peaceful family life and the most beautiful children in the world. He wrote, “They gave me coconuts and pineapples. If I had taken it, I would have had enough food for a week and they didn’t have enough for themselves.”

Between most of his flights, even when he was severely fatigued or ill with chronic fevers, he escaped on his bicycle to spend time with his Indian family. He wrote of “the most beautiful children in the world” and a more peaceful and loving family life than he had ever imagined.

But he also wrote, “The filth these people live in is unbelievable. At one home today, there were 12 kids and three generations living in a basha smaller than mine.” Yet, as his connections to these people quickly grew, he saw beyond their living conditions and preferred to go alone to their villages because others from the base would remark at the uncleanliness and insult his friends or fear catching a disease.

“When I am alone, I get much closer to them and really learn how they live and what they think,” Dad wrote. He said there were many things they could teach Americans.

One morning after a 10-hour flight, he packed up some candy and his camera and started through the jungle trails. He toured a Hindu temple, a tea plantation, and the local boy’s school. Then he went to the homes of Hindu families. His letter said, “Had some very interesting visits with several families and saw the cutest children. I thoroughly enjoyed the afternoon and wish you could have been with me. They gave us tangerines and coconut milk to drink. It was so peaceful and pleasant sitting there in their yard with little kids all around me, that I hated to come back to camp.

“There is nothing wrong with India that a few intelligent, unselfish people couldn’t cure. Of course, if I said that openly here at base, I would be called the most stupid one yet. But I have seen more and asked more questions among the natives than others here. Since I have looked around over here, there are some beautiful places, and if I had you with me, I would be satisfied to stay here.

“But, stop me! I sure spend a lot of time dreaming of that post-war home you write about.” Amidst such daily stress from the intense flight schedule and war, my father was finding peace and beginning to imagine a life among the people of Assam.

He wrote often about his bearer, or house servant, Abdoul. When Mother sent Abdoul a gold watch from the States, he ran outside so as to not be seen crying. He thought my mother looked beautiful and plenty healthy, but he wondered why she never came to visit.

Dad bought a Victrola record player from a departing pilot and Abdoul took command of it, playing his favorites, which were opera. When his tour ended, Dad gave Abdoul a month’s pay and the gold pen he had written all the letters with. Abdoul ran from the basha so as to not be seen crying.

Dad’s roommate was the base chaplain he called “The Preacher.” He wrote mother, “He keeps the drinking and the women parties down,” though the Preacher much enjoyed that Dad would pack bottles of beer in the bulkheads of his airplane that would freeze over the mountains so he could serve ice-cold beer back in the hot jungle.

The Preacher also stowed away on flights to China, and Dad gave him flying lessons over the Himalayas. Dad wrote, “He was like a little kid at the controls, on the adventure of his life.” Dad also visited families in China and wrote, “Went to a remote place and the women still bind their feet and they’re no larger than their hands. Is this the 20th Century?”

It was becoming cold in China but still swelteringly hot in Tezpur. Dad was visiting the infirmary regularly with flu symptoms. By early December 1944 another crew was lost and pilots were refusing to fly. Dad wrote, “There are several who are afraid to fly the Hump, and some of them we used to think of as rocks. One captain was court-martialed when he refused, and got a dishonorable discharge. We lost a ship the other day, or I should say, another one, and everyone is jittery. I don’t enjoy this, but the scariest part for me is working with crew members who are afraid. You never know what to expect from them.”

In late December, just before Dad’s 66th and last flight over the Hump, Tokyo Rose, the Japanese radio propagandist, said in her broadcast that pilots crossing the Hump would die and never return. Dad wrote Mother about what Rose had said and remarked, “Now you better start worrying about me.”

His final trip over the Hump was flown amid a flurry of enemy alerts on the day after Christmas 1944. On that flight, they had to circle Chengkung for four hours waiting for a Japanese attack on that base to end before finally receiving landing clearance. Back in Tezpur, as he taxied in and shut down the empty C-109 for the last time, I imagine that he walked away with very little regret. Along with most Hump pilots and crew, my father was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and Air Medal.

It was Christmas, 1944. Dad’s duties flying the Hump were completed, but the war continued. The war news was disheartening. The Japanese were still advancing in China. The Navy and Marines had returned McArthur to the Philippines after terrible losses, yet a long siege of Japan was anticipated. Predictions of American casualties in an invasion of Japan ranged to the hundreds of thousands.

In Europe, the Battle of the Bulge was underway as Germany stood its last vicious defense. Dad wrote, “I am anticipating the fall of Germany every day. Guess our big bombers really knocked Formosa for a loop, and that gives me a little encouragement and feeling of accomplishment.”

The Dresden firebombing that killed tens of thousands was to come in February 1945. The fall of Berlin came three months later when the Russians captured the Reichstag. Until then, Germany had been under terrible bombardment by Eighth Air Force B-17s. Those operations very likely included several of the bombers that Dad had delivered to Europe in 1943.

In answering Mother’s 265th letter with his 199th (she wrote 275 to him that are lost), Dad’s New Year’s Eve letter reflects the uncertainty felt by many around the world on that night: “If we were together in a quiet place, I could do lots of philosophizing about the passing of the old year. Am happy to have one more year of this unnatural existence behind us, but it is hard to become enthused over the life we face in the new year. However, if we do our part in living our lives properly, I feel confident that we will find the peace and happiness that so often seems to have vanished from the earth.”

Mother had written joyfully that he would be returning soon since he had said he would not need any more instant coffee and other supplies sent by her. But he wrote back that he had no idea when he would be home; he narrowly avoided an assignment that would have held him in India another 18 months. A colleague had been stuck in that duty.

There were more rumors that the flying requirement would be extended by another 100 hours. He wrote, “Don’t get any ideas of when I will return, until you hear me on the telephone, as that is as long as it will probably be.”

The Army was slow to send pilots out of theater and Dad waited another month for orders home. Getting back to the states was a challenge in itself. He flew to Lucknow in north-central India for a week of touring, and made a side trip to the Taj Mahal. Letter number 211 was written from Karachi, where Dad was waiting for a flight out of India.

He left Karachi by hitch-hiking a transport on January 25, 1945. He rode through Abadan, Persia; Cairo; Tripoli; Casablanca; the Azores; then a long flight from there to Newfoundland, New York, and home to Delaware on January 28.

There are many important postscripts to these letters and stories. Warriors suffer many losses far from the battles, long after the war is over. My father contracted multiple sclerosis years after the war. He had thought the cause was his long exposure to carbon monoxide and fuel fumes in old airplanes. The Mayo Clinic, where he received his treatment, had suggested that.

Yet, more recent research has also theorized a viral cause of neurodegenerative diseases, and suggests that a cold virus originating on the Indian sub-continent might be a common cause of both MS and Alzheimer’s Disease. This has caused me to consider a possible implication of my father’s chronic viral illnesses over those months in India, as viral epidemics had been associated with both MS and Alzheimer’s in those regions. Once the virus infects, it may lie dormant for many years and then find a venereal transmission pathway. My mother also died from Alzheimer’s.

When I was young and both my parents were vibrantly alive, I did not know enough to ask for old war stories. The letters written to Mother from Dad in India are a treasure I did not discover until she was moved to a nursing home in the 1990s. She had kept them to herself, hidden away, deep in a secret drawer.

Written from a lonely basha in a Brah-maputran jungle, and from a freezing cockpit high above the Himalayas, they chronicled the heroic experiences my parents shared, and a once true-love cast in the midst of the world at war. And years later, I discovered my father’s photographs.

Early in his India tour, Dad had written that he was surprised and happy to learn that Mother was saving his letters. He wrote to her, “Who knows, maybe someday they will become a diary of all this.” So, here, my parents have come together finally, to tell this story to you.

The author lives in Broomfield, Colorado. Copies of Among Stars Above the Storm may be obtained from the author at: [email protected].

Great article. I had an older, wiser, very world experienced work partner tell me a little about his 5 years in the CBI and flying cargo the including many Hump trips. Upon arrival there, the pilot told them “you have just arrived into the A%$hole of the world”. He didn’t get back to the States until 1946. He mentioned that you could get ANYTHING you desired for a 50 Lb. bag of rice. He was an interesting guy. Jimmy Stewart from Baltimore, MD.