By Mark E. Hubbs

Glen Binge brought his helmet home at the end of World War II. The helmet bears the names and addresses of more than 50 of his comrades. This was not an unusual thing. Many soldiers kept their helmets as souvenirs. But Glen Binge was not a soldier, or a Marine. He was an American civilian who had beaten the odds to survive one of the most famous battles of World War II and three and a half years as a POW in Japan’s most infamous prisoner of war camp.

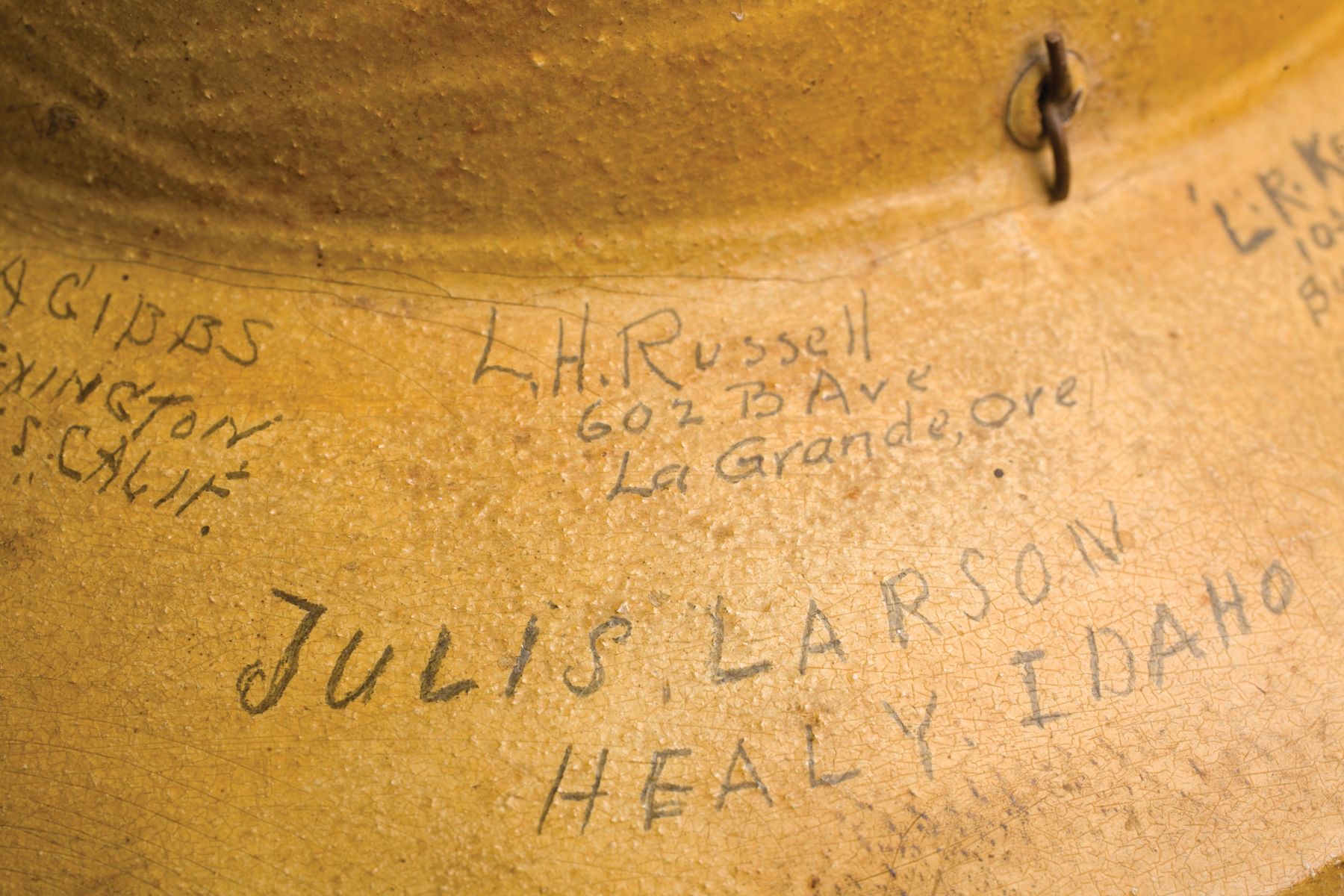

The cloth-covered fiber sun helmet that survived and came home with him is a puzzle. How could such a fragile item survive the rigors of combat and a brutal captivity, especially when over half the men who signed it died at the hands of the Japanese? This is the story of the Wake Island men who signed Glen Binge’s helmet.

At 51, Logan Kay was too old to be scrambling through coral gravel dodging Japanese bombs. That is where he found himself on the morning of December 8, 1941. A force of 27 Japanese bombers struck Wake Atoll within a few hours of the attack against American military installations in the Hawaiian Islands. Wake is 2,300 miles west of Honolulu and across the International Date Line. It was December 8, where Logan Kay of Clearlake Park, California, and his friend Fred Stevens of Sioux City, Iowa, struggled to find shelter. Stevens had a bad case of food poisoning contracted the day before. “Scotty,” as his friends called Kay, helped Stevens to a large steel dredge pipe where they would shelter for the next few days.

The Pan American Airways hotel on Peale Island was in shambles. (Wake Atoll is made up three islands: Wake, Peale, and Wilkes. The V-shaped atoll is nine miles long from tip to tip.) Japanese bombs put it out of business and killed 10 of its Guamanian staff. The China Clipper seaplane, floating at the hotel dock, survived the bombing. Soon, all the Caucasian Pan Am employees and five passengers were in the air, fleeing to Hawaii. Jesus “Seuese” Garcia of Agana, Guam, acted as spokesman for the surviving 35 Guamanian hotel employees who were left behind. They could only stand and watch as the big seaplane winged away. Garcia marched his Chamorros to the island commander to offer their services to defend the atoll.

For the following 15 days, the Marine garrison on Wake held out against repeated Japanese air and naval attacks. Many of the civilians on the island assisted the Marines in both logistics and combat roles, Logan Kay and Fred Stevens along with them. They were among 1,150 civilian contractors employed by the Morrison-Knudsen Company, part of a cooperative of eight construction companies called the Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases (CPNAB). The CPNAB was contracted to build an airfield, seaplane base, and submarine base and to dredge a channel into the lagoon to allow access for submarines.

The garrison endured daily air attacks and on December 11 repelled a naval and amphibious assault with its heavy seacoast guns. A larger, more determined invasion force arrived two days before Christmas, and the well-trained force of Japanese Special Landing Force troops finally overwhelmed the garrison after heavy fighting. In the early hours of December 23, 1941, the Japanese captured 1,621 Americans with the fall of the atoll.

“Come out and give up. The island was surrendered at 7:20 this morning.” Twenty-three-year-old carpenter Rodney Kephart heard the call from his hiding place. Kephart, from Boise, Idaho, assisted in the defense of the island during the long siege by tending the wounded and digging trenches. He admitted after the war, “It certainly was a relief to be free from the suspense of it all, and to be through dodging hell in small parcels.”

As resistance ceased on Wake, the U.S. Marines, sailors, and contractors were marched to the runway and seated in rows facing a line of Japanese machine guns. Logan Kay and Fred Stevens were the only men who avoided capture. They hid in the bush, certain that those surrendering were to be murdered. Indeed, this was the plan of the Japanese troops who held them. Only the intervention of Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka, who commanded the invasion force, prevented the slaughter.

After Kajioka arrived, an interpreter read a proclamation to the prisoners that said, in part, “The Emperor has gracefully presented you with your lives.”

An unknown voice bellowed from the crowd of Americans: “Well, thank the son-of-a-bitch.”

With the exception of a handful of senior military officers and contractors held indoors, the captives remained three days and two nights on the rocky runway. Leal Henderson Russell of La Grande, Oregon, wrote in his otherwise optimistic diary: “23 December—…Rocks hard, rain, wind, no cover and few clothes. Bread and water. Very uncomfortable night.” 24 December—”Still on the rock-pile. Very hard on the unclothed men and those who are ill. Many have dysentery.… Men hard to control while food and water being passed out. Act like wolves….”

Tensions of the previous days relaxed a bit on Christmas morning. One contractor remembered that they were allowed to retrieve clothing, food, and tobacco from their dugouts. Russell recalled that the POWs were allowed to bury their dead and were fed well for the first time. They were marched to the north end of Wake Island and put into the barracks they had used before the beginning of hostilities. Several 40-man barracks were packed with 150 men each, but the men had shelter at last. He recorded on December 27: “Japanese treating us with reasonable consideration.”

Kephart remembered: “We slept so well even the screaming of the Japs didn’t disturb us—that was indeed a welcome Christmas present.”

Three weeks after the fall of Wake, the POWs awoke to see a large vessel, the Nita Maru, standing off the southern shore. She had arrived to transport the POWs to camps in China. “About 350 including the key men were selected and were supposed to stay,” wrote Russell. He became the ranking civilian POW when the Nita Maru sailed away. Another of the Morrison-Knudsen men recorded in his diary on January 12, “All but 360 of the contractors have been sent to Japan today. [He incorrectly assumed the destination was Japan]. Also the service men except 21 Marines who are too badly wounded to go.”

Forty-seven-year-old Glen Binge was like many other men on Wake. The promise of wellpaid work during a bleak economy lured him far from his Galesburg, Illinois, home. It would be almost four years before he would see his children again. Binge arrived at Wake on October 27, 1941, on a nine-month contract. He came ashore with 175 other men from the USS Curtis (AV-4), a seaplane tender that shuttled men and equipment between Honolulu and Wake Atoll.

Sometime after January 12, Binge began to have men sign his helmet. Binge’s sun helmet was not unusual. Hundreds of the white sun helmets were issued by the CPNAB to its Wake Island men. The Marines issued similar sun helmets that were tan and bore the Globe & Anchor emblem on the front. There is evidence that many men recorded names of comrades or had their mates sign their helmets as mementos, but the Binge helmet is the only one known to have survived. It has been a family treasure for 60 years, but its existence has only been brought to light outside the family in the past year.

All of the American names inscribed are from those men who remained on Wake after the departure of the Nita Maru. The 360 contractors who remained were chosen because of their skills in operating heavy equipment. They would continue the military buildup of Wake Island with the same supplies and equipment that they had used for the U.S. Navy. This time, however, the new architects of the island defenses were the Japanese.

Kay and Stevens remained hidden in the scrub brush of Wake Island. They scavenged for food and moved every few days to avoid the Japanese. On March 10, after living in the bush for 77 days, the fugitives stumbled upon 67-year-old Ted Hensel of Burbank, California. “You can’t be living men. You’re already identified as dead and buried!” Hensel retorted. “You two look terrible. Better give yourselves up. The Japs won’t hurt you. They’re treating us fine.” Hensel persuaded the ragged, starving men to surrender.

Russell paints a relatively optimistic picture of his life as a POW. His keen eyes recorded the daily coming and going of bombers, fighters, and ships from Wake as well as the weather and day-to-day activity of the Japanese garrison. He seemed to be very interested in his captors and cultivated cordial relationships with some, even arranging dental work for one of the Japanese with the U.S. contractor doctor.

Russell surely was aware of the suffering that was going on around him. His tone is upbeat in the diary, however, and he refrains from recording adversity except in extreme cases. One such case was the execution of one of his men who had broken into the Japanese canteen and gotten drunk on stolen alcohol. On May 8, Russell wrote, “After breakfast I found that they had arrested Babe Hoffmeister who was out of the compound during the night. Okazaki told me later he had broken into the canteen.… I also heard he was drunk. It is apt to go very hard on Babe as he had been repeatedly warned.”

Two days later, the Japanese gave Hoffmeister a hasty trial. He was found guilty, blindfolded, and marched to his grave. Kay recorded: “The Japs made Hoffmeister crouch on his hands and knees. A Jap officer took his sword, laid the blade on his neck, brought it back like a golf club and then down on his neck, severing his head with a single blow.”

Russell wrote: “May 10th—Julius ‘Babe’ Hoffmeister was murdered this morning. Nearly all foremen and dept. superintendents were called to witness it. Possibly it will serve as a warning to some who still feel that they have some rights here.”

The next morning, with Babe’s murder fresh on their minds, the Japanese evacuated 20 Marines and sailors, who had been recuperating from wounds. One of these men was Pfc. Richard L. Reed of South Whitney, Indiana. Reed was the only Marine to sign Glen Binge’s helmet. Reed and the other recovering Marines sailed away on the Asama Maru, bound for camps in China. Only the civilian contractors remained to toil for the enemy.

The Japanese did not observe the Geneva Convention restriction on using POW labor for war-related projects, and the workers toiled at various military projects on all three islands of the atoll. Extensive antitank ditches, protected by slit and communication trenches, were dug on the outer and inner periphery of all three islands. Barbed-wire entanglements and land mines provided protection on potential landing areas. Inshore from the narrow beaches, an elaborate system of concrete defenses provided interlocking fire at almost any point on the atoll. An estimated 200 concrete and coral pillboxes, bunkers, bomb proofs, and command posts were constructed with POW labor.

Only the occasional U.S. bombing raid or Japanese holiday (when no work was performed) punctuated the monotonous life of the POWs. Russell wrote: “Washington’s Birthday on Wake Island and still prisoners of the Japanese. No change at all. We work, we eat, we sleep, and then we get up and do it all over again.… Rumors fly but even they grow tiresome.”

The rumors of prisoner evacuation became reality on the last day of September 1942. Two hundred and sixty-five captives, including Glen Binge and 21 of his friends who autographed his helmet, were loaded aboard the Tachibana Maru and sent to Yokohama, Japan. Ninety-eight Americans were chosen to stay and continue their work on construction projects.

Most of the men were jubilant that they were leaving Wake. They could not know that their lives as POWs on Wake for the previous nine months had been relatively easy, and that true hell awaited them.

Japanese sailors herded the 265 Wake Island men aboard a crowded train when they reached Yokohama. Soon after they pulled away from the station the train halted long enough for Russell and four others to be taken off for interrogation. Russell was never reunited with his crew. He was liberated on September 15, 1945, at Ohashi, Japan.

Fukuoka No. 18-B became the new home for the remaining 260. This camp, near Sasebo, Japan, was established to provide slave labor for the construction of Soto Dam. The work was backbreaking and the rations slim. Three small bowls of soupy rice per day was the standard fare. One inmate confessed, “I ate garbage while at Camp 18. A man will do anything for food if he is really hungry.”

The meager diet was enforced even if additional rations were available. The Japanese pilfered or withheld Red Cross packages and punished men for “garbaging,” trying to steal offal and vegetable peelings from Korean laborers. One inmate who was six feet four inches tall was reduced to 110 pounds. “I ate anything to stay alive.… I ate toads, roots, grasshoppers—you string ‘em on a wire and throw them in a fire, then eat ‘em like peanuts.”

A series of heartless commanders and senseless beatings by brutal guards exacted a horrible toll on the Wake Island men. The slightest infraction of the rules brought extended beatings with clubs and baseball bats. One survivor was hit repeatedly on the forehead with a rock by a Japanese guard. “I thought my brains were going to explode,” he remembered.

Jesus Garcia, the Guamanian who had worked at the Pan American Hotel, barely escaped with his life. He was pushed from a guard tower and then beaten on the head with bamboo club for an hour.

The first of the helmet signers to die was John F. Niklaus of Germania, Pennsylvania, on January 26, 1943. Japanese records claim he died of “acute pneumonia.” Julius Larson of Healy, Idaho, was next on February 18. James H. O’Neal of Worland, Wyoming, followed on February 27. The Japanese listed the cause of death for O’Neal as “cardiac beri beri.” Acute pneumonia also claimed Andrew Nygard of Long Island, New York, on March 13.

Thirty-one-year-old Lester Meyer of San Francisco, California, failed to salute a Japanese guard. He was beaten with clubs and rifle butts off and on for three days. He died on April 29, 1943, as a result of this torment. The Japanese listed Meyer’s cause of death as “right pleurisy.”

The next to die was Ted Hensel on May 5, 1943. Norman Hill of Clarkston, Oregon, succumbed to “malnutrition” on June 4, 1943. The last of the helmet signers to die at Fukuoka No. 18-B was Lloyd Kent of Burbank, California, who passed away on March 3, 1944.

Thirty-seven-year-old Oreal Johnson of Boise, Idaho, served as the chaplain and lay preacher for the Wake Island men. He provided a short service for each funeral and sang “I Need Thee Every Hour.” Johnson and other men of the burial details were rewarded for their loathsome duties with extra food. The guards enjoyed tossing the rice balls among the starving men to see the melee that would ensue. By April 17, 1944, when the Wake Island men were moved to the Fukuoka No. 1 camp, 53 of the original 260 were dead.

Fukouka No. 1 was a large camp that housed American, Australian, British, and Dutch POWs. Conditions improved to some degree at No. 1. The rations were still sparse, but some Red Cross packages did get through. The Japanese guards more often slapped their charges around instead of beating them with clubs. The biggest difference was the nature of the work. They built a new airfield at No. 1 and avoided the backbreaking labor that had killed so many men at the Soto Dam.

The death rate plummeted, and no more signers of Glen Binge’s helmet met their end after leaving Fukouka No. 18-B. Binge also began to make friends outside his Wake Island family at No. 1. Gunner William Davis and Sergeant Benjamin Regan, both from London and veterans of the Royal Artillery, added their names to the helmet. The outside was covered with autographs, so they scrawled their names on the inside of the crown next to where Glen had placed his own mark so many months before. Dutch soldiers, H. Buys, W.F. Zonneaberg. and P. Van Veen, signed near their British allies. By enlarging his network of friends, Binge also broadened his potential access to resources. This may have contributed to his survival.

During the last year of the war, the surviving men who were evacuated from Wake in September 1942 were being separated. Labor details were dispatched away from Fukouka No. 1 without regard to the men’s original organizations.

In late August 1945, red, white, and blue parachutes began floating to earth above food cartons at Fukouka No.6 near Orio, Japan. The Japanese had surrendered, and hostilities ceased on August 15. American bombers began parachuting food and clothing to the starving Allied POWs at camps all across Japan. On the morning of September 1, 1945, several of the officer POWs approached Rodney Kephart with an armload of silk canopies.

“Can you make us an American flag so we can have an official raising of the colors at the same time the Japanese sign the surrender tomorrow morning?” they asked. The POWs had learned that the official surrender ceremony was to take place the following day. Kephart was the only man who knew how to operate a temperamental Japanese sewing machine at the camp. Kephart and another POW worked 16 hours straight to have the flag ready in time. He was too exhausted and overcome with emotion to attend the ceremony. He lay in his bunk sobbing as his flag was raised over the camp.

Kay and Stevens, the men who hid out for so long on Wake, somehow managed to remain together. They were liberated on September 19, 1945, at Camp No. 23 at Izuka, Japan. George Weller, a war correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, accompanied the liberation teams and met Kay at Camp No. 23. Weller recorded Kay’s remarkable story and transcribed the diary he kept while on Wake. Weller and Kay were photographed with a white sun helmet that bore the names of Wake Island dead. Much like Glen Binge, Kay had saved his own souvenir helmet that bore the names of scores of Wake Island men. That photograph was published in the Chicago Daily News with the caption “Memento of Terror.”

As the survivors of the hell camp at Fukouka No. 18-B began their long journeys home to the United States, they did not know that all 98 of their comrades left on lonely Wake Atoll had been dead for almost two years.

The day-to-day record of POW life at Wake ended when Russell clambered aboard the Tachibana Maru. The routine of the remaining 98 did not change, however. Only increasing U.S. bombing raids and the loss of one of the 98 interrupted the monotony. An American was caught stealing food in July 1943. After a brief investigation, a Japanese lieutenant wielded the sword that removed the head of the unknown American. Captain Shigimatsu Sakaibara, the new island commander who had been whisked ashore by an Imperial Navy bomber from Kwajalein in December 1942, presided over the murder.

The U.S. Navy also was tightening a noose around the atoll. Extensive submarine patrols harassed all shipping coming in and out of Wake. This increased attention aggravated the island commander. Sakaibara and his subordinates were certain that an invasion was imminent. In reality, the United States had no intention of forcing a landing on Wake. As with most Japanese-held islands that did not have a tactical or strategic role for further campaigns, they were merely isolated from their source of supplies and left to wither on the vine. Bombings were designed only to deprive the enemy of the use of their airfield, seaplane base, and port facilities.

A U.S. carrier task force, which included the USS Yorktown (CV-10), arrived offshore on October 5, 1943. During the following two days the task force dropped 340 tons of bombs on the atoll, and the accompanying cruisers and destroyers hurled 3,198 eight-inch and five-inch projectiles. The raid did extensive damage to the infrastructure on the atoll, and 31 Japanese planes were destroyed on the ground. This was the largest U.S. raid on the atoll up to that time. Sakaibara was certain that the armada assembled offshore included a landing force. He decided that the troublesome prisoners must be killed to eliminate the threat they might pose during the coming invasion.

The Headquarters Company commander, Lt. Cmdr. Tachibana, was ordered by Captain Sakaibara to move the prisoners from their compound to an antitank ditch on the northern tip of Wake Island. There, in the waning afternoon light of October 7, 1943, Lieutenant Torashi Ito, of the Headquarters Company, had the Americans lined up and seated along the ditch facing the sea. They were blindfolded with their hands and feet bound. Three platoons of Tachibana’s company assembled behind them and opened fire with rifles and machine guns.

A Korean laborer who witnessed the massacre testified later, “All prisoners, both dead and wounded, were bayoneted.” The names of 19 of the dead men appear on Binge’s helmet.

The bodies of the Americans then were unceremoniously dumped into the ditch and covered with coral sand. The indignity suffered by the prisoners was not complete, however. The following day, a report from an enlisted man that he saw one of the prisoners escape during the confusion of the massacre prompted the disinterment of the bodies. The corpses were dug up and counted, then hastily reburied. The sailor had been correct; one American was missing. The Korean laborer also saw the man flee and recognized him as “Mr. John,” his favorite among the Americans. That man, whose full name has never been discovered, was recaptured a week later. Captain Sakaibara personally beheaded the lone escapee. There were two men named John among those murdered by the Japanese. One was John Martin of Pomeroy, Washington, who autographed Glen Binge’s helmet many months before.

The mass grave on Wake lay forgotten for two years despite several unanswered queries from the International Red Cross to Japanese officials. When news reached Wake in August 1945 that the United States had prevailed, the Japanese, for some reason, felt it necessary to disturb the grave of the POWs once more. They clumsily extracted the bones from the ditch and moved them to the U.S. cemetery that had been established on Peacock Point after the battle. The remains were dumped into a small, single grave. The cemetery was roped off, and wooden crosses were erected and painted in preparation for the expected arrival of U.S. forces.

When questioned about the last 98 Americans left on Wake, each of the Japanese told an identical rehearsed story. The Americans had been placed in two bomb shelters to protect them from their countrymen’s bombs. One of the shelters had received a direct hit, and all the occupants had been killed. Those in the other shelter panicked, killed a guard, and fought their way out of their compound. They had been cornered on the beach at the north end of Wake Island, and all had fought to the death.

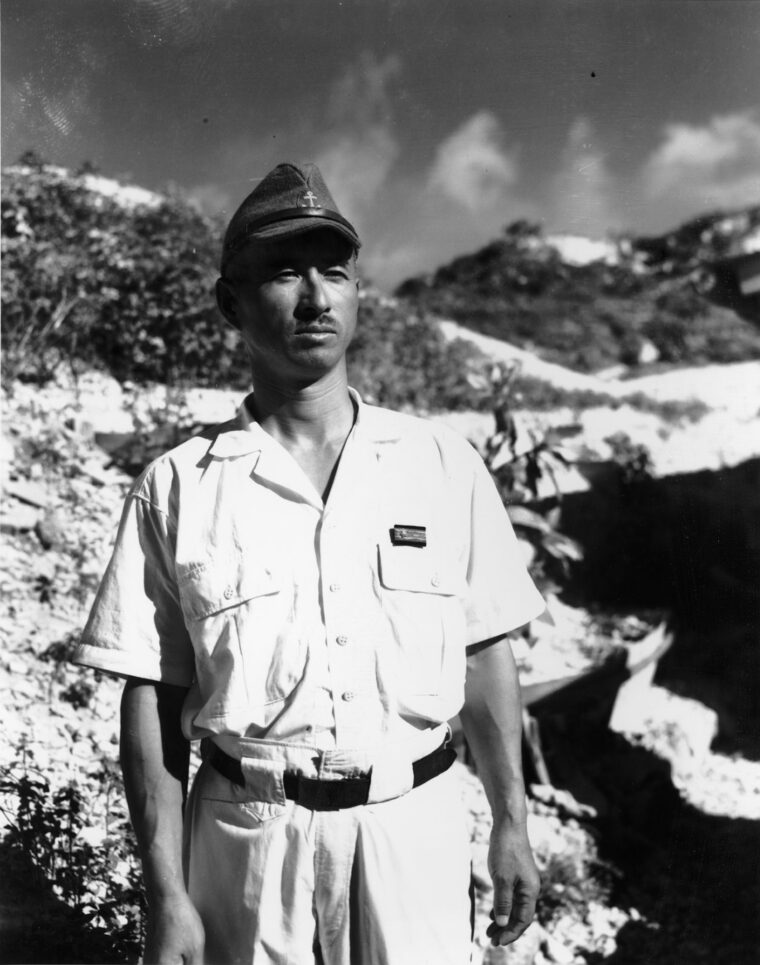

Soon after the Japanese surrendered Wake Island on September 4, 1945, Captain Sakaibara and 15 of his officers and men were arrested and sent to Kwajalein to stand trial for the murder of the 98 POWs. Two men committed suicide en route and left statements that implicated the captain and others. While being held during the trial, Lieutenant Ito also killed himself and left behind a signed confession. After being confronted with this statement, Sakaibara finally confessed that he had ordered the murder of the 98 Americans and stated that all responsibility should rest on his shoulders. The trial concluded with a sentence of death for Captain Sakaibara and Lt. Cmdr. Tachibana.

Eventually, a reprieve was granted for Tachibana, whose sentence was commuted to life in prison. Sakaibara, however, was transported to Guam to await his fate. There, on June 19, 1947, he was executed by hanging along with five other Japanese war criminals. Sakaibara’s last statement was filled with Japanese stoicism: “I think my trial was entirely unfair and the proceeding unfair, and the sentence too harsh, but I obey with pleasure.”

The war was over, the murders had occurred more than three years previously, and the public had already been outraged with the news of similar massacres in the Philippines and in the European Theater. No national acknowledgement of the Wake Island massacre ever materialized.

In Section G of the Punchbowl National Cemetery in Honolulu, Hawaii, lies a large, flat, marble gravestone. At 5 by 10 feet it is the largest in the cemetery. On it are listed the names of 178 men. This common grave holds the remains of all the unidentified military and civilian burials repatriated from Wake Island in 1946. Many of these men were killed during the siege, and circumstances did not allow proper burial and identification. Of these names, 98 represent the men who were murdered by the Japanese in October 1943. After several years of unsuccessful attempts to separate the remains and identify them, they were interred together during a ceremony at the Punchbowl in 1953.

I visited Wake Island for the first time in 1994. The bland black-and-white newsreels of the Pacific War that had burned into my psyche did not prepare me for the Technicolor paradise that I encountered at the Wake Island Launch Center air terminal. A large sign declares, “Wake Island Airfield, Where America’s Day Really Begins.” Indeed it does, as Wake is on the west side of the International Date Line. It was difficult to imagine Wake as the desolate hell that it was in 1941.

I drove past the end of Wake Island, across the causeway to Wilkes Island, to a point on the map that said “POW Rock.” A shiny new sign read: “POW Rock, no vehicles allowed beyond this point.” A coral gravel walkway led to the shore of the lagoon where a four-foot-high dome of coral thrusts its way up among smaller boulders. Here, an anonymous American chiseled a brief but poignant message that has come to symbolize the sacrifice of all 98 men.

As the afternoon sun tinged the lagoon with a warm yellow glow and the surf crashed in the distance, I traced a roughly chiseled inscription in the rock with my finger, “98 US PW, 5-10-43.” Morrison-Knudson had installed a bronze tablet that lists the names of the 98 nearby. This tablet and boulder with its simple inscription have become the island’s memorial for a mass murder that took place nearly 70 years ago.

The sun helmet is also a memorial to all Wake Island defenders, but specifically to those men who autographed it for their comrade, Glen Binge. The fragile cardboard and cloth headgear’s survival is testimony to the perseverance of those men who came home, and a cenotaph for those men who died at the hands of a brutal enemy. n

Author Mark E. Hubbs is a retired major in the U.S. Army Reserve. He is a historian and archaeologist and works for the U.S. Army at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama.

This is an excellent article.