By Eric Niderost

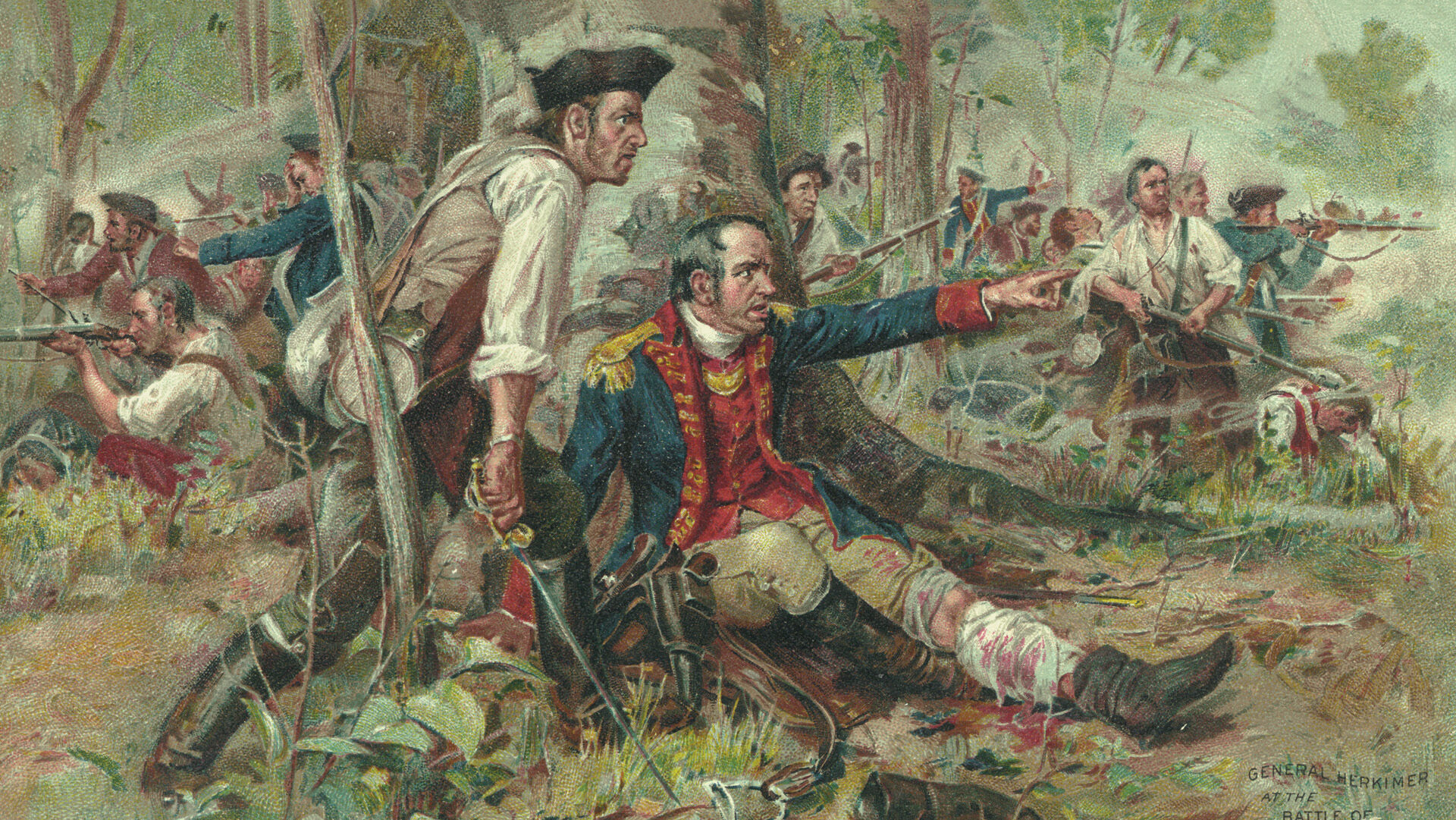

Private Ransom Clark of the 3rd U.S. Artillery was looking forward to the time when his column would finally reach Fort King in the Florida Territory. It was December 28, 1835, and Major Francis Dade was leading two companies of soldiers drawn from the 2nd Artillery, 3rd Artillery, and the 4th Infantry regiments on an urgent mission to reinforce the isolated, undermanned outpost. Clark liked Dade, even though the yawning social chasm between officer and enlisted man sometimes made it hard to establish even a professional rapport.

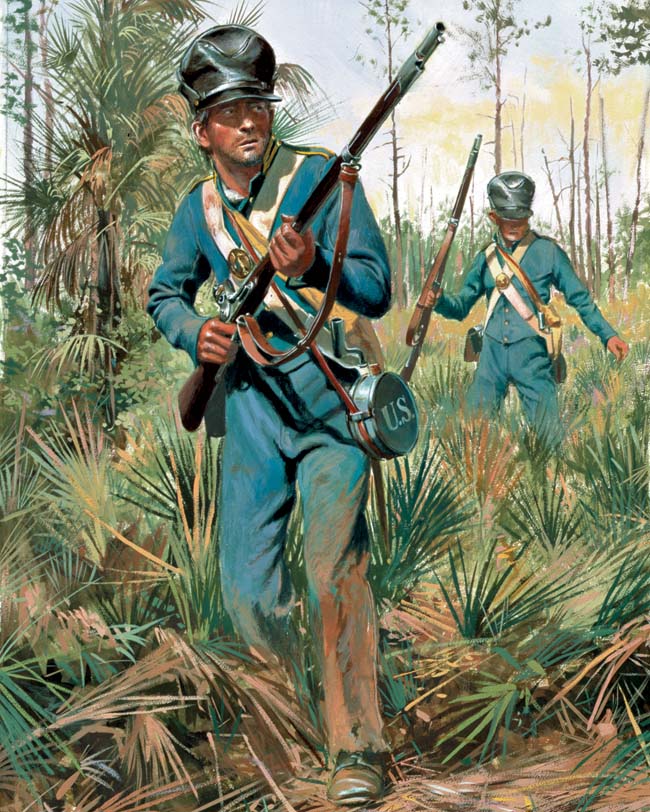

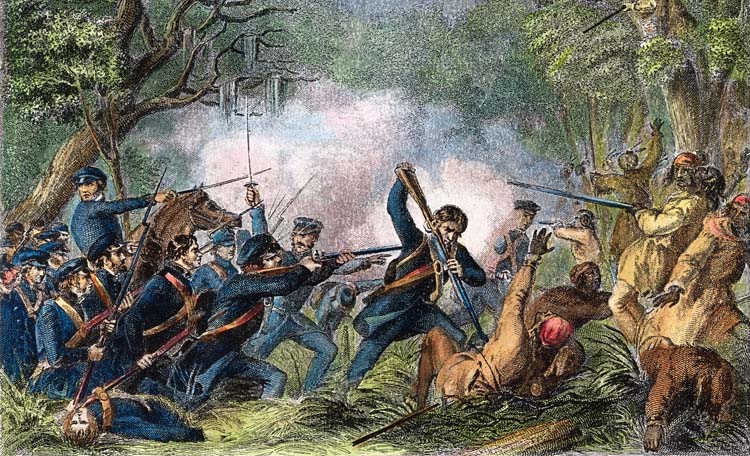

The column trudged on a military road hacked out of the semitropical wilderness by brawny axemen some time before. It was a snaking trail that crossed rivers and several hammocks, which were tracts of hardwood trees and shrubs that were higher than the surrounding bogs and marshes. The 110-man column stood out in sharp relief against the verdant vegetation that crowded the sides of the road. The men’s sky-blue uniforms merged to form a winding, azure-colored snake.

Warriors from the Seminole tribe were watching. Even the rawest U.S. Army recruit was aware of their unseen but always felt presence. Tension was highest at night, and at vulnerable places like river crossings. But now they marched into high ground, where trees were not so thickly clustered, and it would be harder here for the Indians to stage an ambush—at least that was how it seemed to the soldiers. The morning had been cold and drizzling, so most of the men wore standard-issue blue wool overcoats.

Clark and the rest of the command carried Model 1816 flintlock muskets, arms that were inferior to the rifles that many, if not all, the Seminole warriors carried, yet serviceable enough in most cases. Keeping your powder dry was not just a proverb; indeed, it was a matter of life and death. For that reason, the soldiers carried their muskets muzzle down and under their greatcoats against the continuing drizzle. Eventually the misty droplets ceased falling, but the air was still damp and chilly, so they kept their muskets in place under their coats.

Major Dade called in the flankers. Although there seemed no pressing need for such a precaution, given that the surrounding ground seemed more open, the column would make better progress if everyone were together. The advance guard was entering what looked like a pine barren, with tree trunks so straight and tall they almost seemed to pierce the sky. The forest floor was carpeted with pine needles and palmettos—palm-like shrubs whose long, finger-like leaves splayed out like miniature fans.

The palmettos were only a few feet off the ground, too low for a man to stand behind, but perfect cover for a warrior in a squatting or prone position. Unfortunately, in the ebullient mood that was coursing through the ranks little thought was given to these possibilities. Feeling a surge of optimism, Dade halted the column and addressed the men in a loud voice. “We have now got through all the danger,” he shouted, “and if you keep good heart, I’ll give you three days [off] for Christmas!”

The announcement was met with cheers, but moments later a shot rang out from the palmettos, and Dade’s chest exploded in blood. Before his men could react to this stunning development, a huge volley fired by scores of rifles blasted into the sky-blue ranks. The volley came from as many as 200 warriors concealed beneath palmettos and perched in pine trees. The storm of lead cut down scores of soldiers, leaving only half of the command on its feet and able to offer any resistance. The blood-soaked conflict known as the Second Seminole War had begun.

uniforms of light blue kersey, carry model 1816 flintlocks.

The Seminoles were a created tribe; in other words, the tribe was formed over the centuries in response to the incursions of the white man. Its origins lay in the 16th century when Spanish explorers probed the Florida peninsula. The slow coalescing of Spanish influence culminated in the founding of St. Augustine on the Atlantic coast in 1565. The Spanish presence was limited mostly to coastal enclaves, but their presence had a profound effect on the Indian inhabitants of the interior. Natives in the immediate area were conscripted as laborers. Those who resisted the Spanish were either killed or sold as slaves. The Europeans also brought diseases with them that had a catastrophic effect upon the Native American population of Spain’s new territory of Florida. By the 18th century, the native tribes that had populated Florida at the time of Christopher Columbus’ landing were virtually extinct.

It is said that nature abhors a vacuum. The same thing can be said about human population dynamics. The original inhabitants had disappeared, but the land was fertile and abundant with game. Native groups from the north filtered in and adapted quickly to their new homes. Some were voluntary immigrants, while others were displaced by the frequent colonial and tribal wars that plagued the region in the second half of the century.

Most of these new arrivals people were Creeks. They were both Upper Creeks, originally from Alabama, and Lower Creeks, originally from Georgia. They spoke two different languages, but both gave a Creek foundation to the embryonic Seminole nation that was forming. The origin of their name is disputed and open to several interpretations. To the Seminole nation today, it is derived from “yat siminoli,” or “free people,” or perhaps “runaway.” Others claim it is largely Spanish in origin and is derived from “cimmaron” and roughly means wild and untamed, or perhaps again, “runaway.”

Whatever they were called, the Seminoles quickly sank roots into the new land, making it their own. Florida was still Spanish, but Spain’s physical possession was confined to a few precarious footholds. But change was coming. The United States bought Florida from a rapidly declining Spain in 1821, and these new white men were of a different breed. Land-hungry and aggressive, the Americans set covetous eyes on Seminole territories.

There were other issues as well. Over the years, the Seminoles had welcomed runaway slaves from Georgia and Alabama and fully integrated them into the tribe. Some even rose to great prominence, becoming respected leaders and warriors. Scandalized by the loss of their property, southern slaveholders not only wanted their slaves returned, but also wanted to block the Seminoles from providing a home for future refugees.

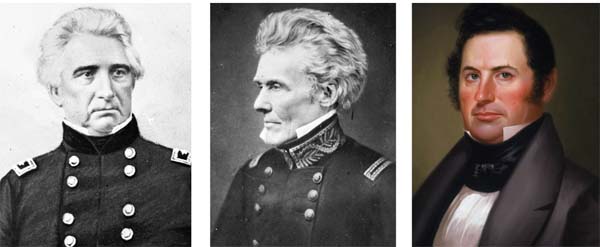

The First Seminole War occurred before the United States had formally acquired Florida. Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson, fresh from his triumphal victory over the British at New Orleans in 1815, invaded Spanish territory in 1818. He conducted a series of skirmishes, arduous marches, and relentless pursuits of an elusive enemy over a two-month campaign. The Seminoles were not in any way decisively defeated, but the way Jackson openly, even contemptuously, ignored Spanish sovereignty persuaded the Spanish to abandon the province forever.

The Spanish were expelled, and it would soon be the Seminole’s turn. In 1823 the U.S. government negotiated the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminole nation. On paper it looked reasonably fair, but this treaty was more deceptive than it appeared. The Seminoles were given a four-million-acre reservation in central Florida, but in accepting this deal they were forced to give up their much more fertile homelands further north. The lands that constituted their new reservation were marshy, had poor soil, and produced low crop yields. Game became increasingly scarce on these lands, and there were reports of Seminoles starving.

Friction with whites increased dramatically. Driven to desperation, some Seminoles began to raid white farms to steal cattle to survive. Demands by whites for black Seminoles to be returned to their owners also created difficulties. But when the Seminoles’ old nemesis Jackson became president of the United States, the Seminole days of relative freedom were numbered.

Jackson, nicknamed “Old Hickory” for his toughness and intransigence, was aided and abetted by the popular mood of the day. The eastern seaboard was filling in rapidly as the European white population grew, but large tracks of land were still held by Native American tribes. The prevailing American attitude held that the Indians were nomads, rootless hunters and gatherers who had no fixed abode. It followed, then, that eastern tribes—at least, what was left of them after 200 years of war and disease—could go west, exchanging their old homes for new ones in Indian territory (i.e., modern-day Oklahoma).

In this all-too-rosy scenario, everyone would profit. Land-hungry whites would acquire some 100 million acres of territory east of the Mississippi, and the natives would be free to roam and hunt the wide-open spaces of the west. The idea that the Iroquois, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Seminole peoples were agriculturalists with deep roots to the land never seem to have occurred to white Americans.

There were about 4,000 Seminoles in Florida, perhaps a little more, but that relative handful was still too many for Jackson. He sent diplomat James Gadsden to Florida to open negotiations with the Seminole nation. Gadsden, a South Carolinian, had negotiated with the tribe before, and looked upon them with ill-disguised contempt. Nevertheless, he was willing to paint the new treaty in the best possible light. The idea was to send a tribal delegation west to scout out their proposed home in Indian Territory. Several chiefs would look around, and if they liked what they saw, the removal treaty would be ratified and go forward.

The chiefs spent five weeks on horseback examining the western lands, and they emphatically did not like what they beheld. Used to a warm, humid, and semitropical climate, they found the bone-dry, hot, and dusty plains of Oklahoma extremely uninviting. Even worse, they would have unfriendly, if not actively hostile, neighbors. While it is true many Seminoles had Creek roots, the two tribes had become estranged in more recent decades.

As soon as they returned home, the chiefs expressed their dislike of the Indian Territory’s land, weather, and their prospective neighbors. Their protests fell on deaf ears. When the Treaty of Fort Gibson was drawn up in 1833, the document set forth that the chiefs were “well satisfied” with the land and would start their “removal to their new home.” Seven Seminole chiefs signed. But they did so under coercion, for they were told that if they did not affix their name to the document, they would not go home.

It was around this time that Osceola enters the story. Although not a chief, he was nevertheless a strong and respected warrior whose charisma was begging to be felt. Historians debate his ancestry because his mother, a full-blooded Creek, was married twice. After her first husband, a full-blooded Creek, died, she married a white trader named William Powell. Osceola was therefore nicknamed Billy Powell in his youth, but that does not prove that the white trader was his biological father.

Osceola was raised as an Indian and considered himself a Creek and, later, a Seminole. The Creeks and Seminoles had a matrilineal system that traced a person’s decent from the mother. Osceola soon became one of the leaders of the resistance to forced emigration.

On April 23, 1835, Indian agent Wiley Thompson summoned a dozen Seminole chiefs and prominent warriors, one of whom was Osceola, to a parley at Fort King in north-central Florida. Thompson was fairly sympathetic to the Indians’ plight, but his good will only went so far. Colonel Duncan Clinch, a big man who weighed 250 pounds, was also present. Clark’s massive bulk, both literally and figuratively, gave weight to his arguments. The chiefs were told that the Seminoles were to leave as soon as possible. This came as a shock, given that most believed that they were going to be allowed to stay at least 20 more years.

Thompson also demanded that the chiefs sign yet another paper, this one confirming that they would abide by the treaties. Eight of the 12 chiefs reluctantly signed, but the other four refused to sign. Clinch unleashed the full fury of his anger on the chiefs who held out. He warned them that military force might be brought to bear against the Seminoles if they did not comply. Thompson signaled his displeasure by declaring that the U.S. government would no longer consider those chiefs who refused to sign as official representatives of the Seminole nation.

Tensions mounted as the weeks passed. Osceola had a habit of coming to Thompson’s office to express Seminole grievances. At one point during a heated argument, Thompson had Osceola arrested, clapped in irons, and briefly imprisoned. As time wore on, the incidents escalated. For example, seven whites in Alachua County assaulted five Seminoles who had been sitting around a campfire minding their own business. The Seminoles defended themselves. When the smoke cleared, one Seminole was dead and another wounded. Native Americans believed that if a life was taken, then the aggrieved party had the right to exact revenge.

In August 1835, Private Kinsley Dalton, a mail courier, was ambushed and killed. Clinch and others began to voice alarm that a full-scale Indian uprising might be imminent. Clinch asked for reinforcements, but he would have to wait for them to arrive. Meanwhile, he had only 500 Federal troops in Florida.

Events then moved at a lightning pace. The Seminole chiefs convened a tribal council. The consensus was that their people should stay in Florida. They issued an ultimatum to the members of their tribes stating that anyone who attempted to obey the white man’s decree would be killed. Chief Holata-Emathia, known to the whites as Charley Emathia, turned a deaf ear to the warning. He brought 400 of his people to Fort Brooke, which was situated on the Hillsborough River in west central Florida, as a preliminary step towards relocation. Osceola killed Holata-Emathia on November 26 for his disobedience. It was a signal to whites that the majority of the tribe was determined to stay and were willing to fight if necessary to avoid removal.

Micanopy was considered the top-ranking chief of the Seminoles, but the middle-aged chief was past his prime. For that reason, the chiefs appointed Osceola as their tribal war chief. Micanopy served in an advisory capacity. Once they had chosen their military leaders, the Seminoles began planning the operation that the whites would eventually dub the Dade Massacre.

Dade’s 110-man column had been dispatched from Fort Brooke to reinforce the troops at Fort King, who were being threatened by Osceola. The Seminoles’ meticulous planning paid off. The first murderous volley, which was unleashed when the soldiers were 40 miles from their objective, crippled Dade’s force. The major’s shattered command was never able to recover.

The volley also caught the soldiers, who were marching two abreast, carrying their weapons underneath their greatcoats to protect them from a drizzling rain. Trying to quickly unbutton greatcoats to return fire was a difficult task, made worse by the screams of the wounded and the blood-curdling war cries of Seminoles ringing in their ears. When Dade was slain, Captain George Gardiner took command of the survivors. He was a bantam rooster of man, only five feet tall. His calm example, combined with his soldiers’ training, steadied the men.

The column had a six-pounder cannon with it. An artillery crew immediately put it into action. They fired grapeshot that peppered the pine stands and vegetation. It killed a few Seminoles and bought the surviving soldiers enough time to organize their defense. For the next hour, the warriors remained under cover. Perhaps as many as 40 America soldiers survived the initial attack.

During a lull in the fighting, Gardiner and the survivors hastily built a low breastwork from pine logs. Gardiner made sure that any wounded soldiers were brought into the makeshift fortification and that the survivors collected ammunition from the dead. Chief Alligator observed Gardiner’s actions and was impressed by his leadership skills and courage.

The Seminoles decided to finish the survivors off with a direct assault on their hastily constructed entrenchment, but the survivors repulsed the Seminole assault. Then, the Seminoles tried to pick off the rest of the soldiers one-by-one. The Native Americans were superb shots. They killed many of the soldiers with shots to the head. The fortification was soon riddled with bullets. The Seminoles kept the soldiers pinned down with a steady harassing fire even when no targets presented themselves.

The Seminoles then stormed the breastworks a second time. They succeeded in wiping out the remaining soldiers; however, several men ultimately survived their wounds. One of these men was Private Clark, who was wounded five times, including a graze on his head and a ball in the right arm, right shoulder, thigh, and lung. Despite these grievous wounds, Clark managed to crawl 60 miles back to Fort Brook.

The shocking news of the Dade Massacre motivated Clinch into launching an immediate offensive against the Seminoles. The original intent was to attack the Seminole stronghold on the Withlacoochee River 90 miles north of Fort Brooke. Clinch had 200 regulars and approximately 500 volunteer militiamen whose enlistments were due to expire the next day, which was January 1, 1836. But the force would have to cross the Withlacoochee. When they reached its banks, they found the river was much swifter and more formidable than expected. There was neither a bridge nor a ford, and the only available boat was a leaky canoe.

Clinch ordered an advance guard of regulars to cross to the opposite bank. Their passage was slow and tedious. Nevertheless, they succeeded in establishing a small bridgehead. The Seminoles promptly attacked the bridgehead. The small toehold across the Withlacoochee could not be maintained, much less expanded, and the advance guard soon withdrew to the safety of the near riverbank. The Clinch offensive had ground to a complete halt.

Maj. Gen. Edmund Gaines was the next officer to try his luck, but his campaign also failed, so badly that it nearly became a fiasco. Poor planning, a crippling lack of supplies, and determined and stubborn resistance by the Seminoles all played a role in Gaines’ defeat. At one point, a large force of Seminoles succeeded in besieging Gaines at his fortified encampment, named Camp Izard. His soldiers had to eat their horses and mules before a rescue party extracted them.

Yet another high-ranking general tried his hand against the Seminoles. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott was one of the finest soldiers that America ever produced and was capable of true brilliance when pitted against a conventional enemy. But the Seminoles were an unconventional enemy that did not adhere to the principles of European warfare. Scott’s elaborate plan called for three columns to converge and trap the Seminoles at Withlacoochee Cove. It was a grand plan that was Napoleonic in its conception. Scott’s plan might have worked against conventional forces, but his offensive was plagued by delays. By the time his forces reached the village at the cove, the Seminoles were long gone.

The U.S. Congress, which was growing increasingly desperate and more than a little embarrassed by the Army’s inability to crush the Seminoles in a timely manner, appropriated $1.5 million for the conflict. They passed a law that would allow the militia to serve for a one-year period. The regular army expanded the forces arrayed against the Seminoles to a paper strength of 12,539 men, but the actual force size was much smaller. It eventually reached slightly more than 8,000 by 1839. What is more, the U.S. Army had to rely on militia of dubious quality to reach the numbers it needed.

By late 1836, the war was still dragging on with no end in sight. Richard Keith Call, the newly appointed Governor of Florida Territory, was also a militia general who felt his armed civilians could do a better job than the professionals. It turned out they could not do a better job, and he was relieved of command after yet another abysmal failure.

The matter, which was becoming a political and military controversy, was handed over to U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Thomas Sydney Jesup, and at first he met with some limited success. Jesup managed to take a Seminole village near the Hatchee-Lustee River, an encampment that included a number of women and children and 1,400 head of cattle. The warriors had escaped to fight another day, so Jessup’s triumph was more apparent than real. The general grew overconfident, especially when the paramount chief Micanopy and several other lesser leaders came in and surrendered. But Osceola, the true mastermind of the resistance, was still at large.

It was at this point that Jesup committed one of the most controversial acts in the entire war. He called for a parley under a flag of truce, and once Osceola came in, he was almost immediately clasped in irons and put in prison. A flag of truce was supposed to mean safe conduct, an assurance that all parties could meet without fear of attack or imprisonment, but that concept was reckoned to be inapplicable under the circumstances.

In the 19th century, a nation’s honor was supposed to be sacred. Jesup’s treacherous action caused not only a scandal, but also a national uproar; the general had sullied the national honor. In so doing, he left an indelible stain. It was an infamous action that would be remembered for generations to come. Jesup spent the rest of his life defending his actions, but never quite lived them down.

Already sick when captured, Osceola died in prison about three months later. Seminole resistance, initially crippled, gained new life when several chiefs escaped from St. Augustine’s Castillo de San Marcos, a famed and venerable relic of colonial Spain. Probably the most formidable escapee was Coacoochee, whose name means “bobcat” and who was just as charismatic and resourceful as Osceola. The dying embers of resistance to removal flamed anew. This produced great consternation in both the U.S. Army and the American public.

But public opinion soon began to change, with many saying the heroic Seminole resistance earned them a place to stay in Florida. Indeed, the public was heartily sick and tired of the whole affair. The cost of the war was spiraling out of control. The war also coincided with the young nation’s attempt to recover from the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1837.

The casualty lists were also growing, and not just from battle. The semitropical climate fostered disease, which was borne on swarms of mosquitoes that bred in the primeval swamps of central and southern Florida. Malaria, dengue, and yellow fever were common. Other debilitating diseases from which the soldiers suffered were dysentery and tuberculosis. Florida was “a most hideous region to live in,” wrote Jacob Motte, a 26-year-old army surgeon. “[It was] a perfect paradise for Indians, alligators, frogs, and every other kind of loathsome reptile.”

A soldier often finds himself “wading in morasses and swamps waist deep, exposed to noxious vapors and subject to the whims of drenching rains or the scorching sun of an almost torrid climate,” added Motte. It got to the point where the serving soldiers began to think that maybe the Indians should be left alone. “The government is in the wrong…the natives used every means to avoid a war, but we forced them into it by the tyranny of our government,” wrote Major Ethan Allan Hitchcock.

American generals still thought in a European linear fashion in which the object of a campaign was to bring an enemy to battle. In such an approach, the goal was to win the war in one decisive clash. It took considerable time for the U.S. Army to realize that the Seminoles were not going to play by the conventional rules. The truth ironically dawned in the aftermath of the one pitched battle of the war, fought at Lake Okeechobee on December 25, 1837.

Most Americans lacked any appreciable knowledge of central and southern Florida. This was due in large part to the nature of the swamps and seemingly impenetrable marshes filled with alligators and poisonous snakes. Lake Okeechobee, which means “Big Water” in Seminole, was indeed gigantic. The lake was 35 miles wide and covered approximately 730 square miles. Its existence even as late as 1828 was unsubstantiated. The main force of so-called hostiles had their main camp not far away from the lake. The chiefs leading the Seminole main force were Abiaka, Alligator, and Coacoochee. The whites knew Abiaka by his English name of Sam Jones.

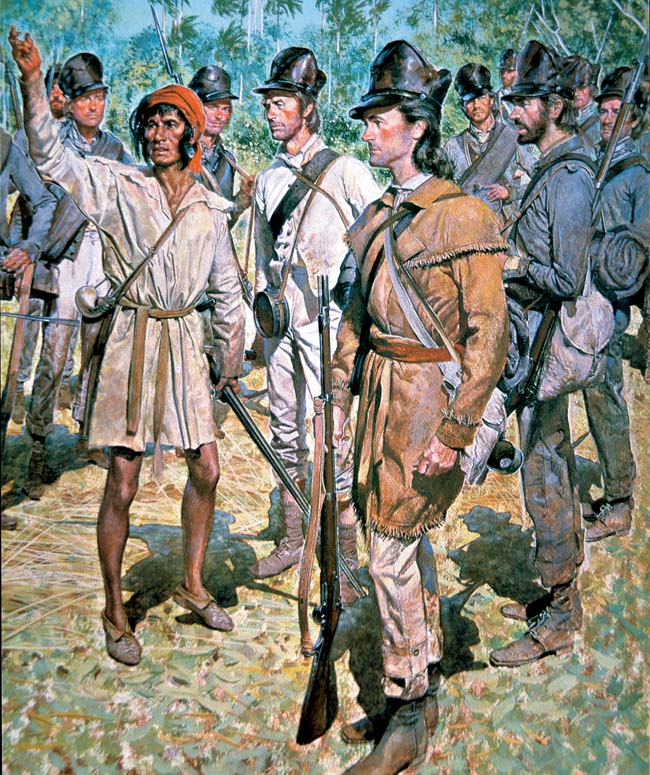

Colonel Zachary Taylor led a column against this stronghold, a force that included around 800 regulars, 200 Missouri volunteer militia, and 50 Delaware Indian scouts. The prospect of surprising the Seminole camp was nil, because 10 of Abiaka’s warriors were shadowing Taylor’s every move. These scouts, experts at concealment, wrapped themselves in moss and partly submerged themselves in marshy ground amid saw grass and palmettos.

his waist. The enlisted men behind them wear the folding black leather forage cap that was first issued in 1833.

Taylor’s troops came upon a fairly dry open area where some Seminole cattle and horses were contentedly grazing. The animals seemed to have but one attendant, but instead of fleeing, or even taking a few pot shots at the soldiers before retiring, he rode forward and surrendered without a fight. The caretaker was quite willing to be interrogated. He informed all of those who listened that a large Seminole camp was situated on a nearby hammock (elevated stand of trees).

A group of Missouri volunteers went forward to scout the position, and when they returned they must have made it clear they did not like what they saw. The Seminole position was indeed on a hammock, but it was surrounded by a sawgrass marsh a half a mile wide that protected the hammock like a natural moat. Horses could not be used, because the sawgrass was firmly rooted in mud and water three feet deep.

The sawgrass grew up to five feet tall in places, but the Seminole had deliberately carved paths into the dense shrubbery like spokes of a wheel. These paths seemed inviting avenues for the attackers to reach the hammock, but they also provided clear avenues of fire for the defenders. The Seminoles had even made notches in trees in which they could rest their rifles and take careful and potentially deadly aim.

Taylor called all his officers together for a council of war. The matter was a mere formality because the colonel had already decided on a frontal assault against the Seminoles defending the hammock. Colonel Richard Gentry of the Missouri Volunteers politely objected. Instead of a frontal assault, he proposed a flanking maneuver to the right or left. The idea was never given any serious consideration, though. Taylor declined to send scouts to reconnoiter the enemy’s flanks to gauge whether such an attack was possible.

A professional soldier to the core, Taylor could barely conceal his contempt for people he must have considered rank amateurs in the art of war. “Colonel Genry, are you afraid to attack the center through the swamp?” asked Taylor. Gentry was stung by this statement. “No sir, if that it your order, it will be that way,” he replied. Taylor ordered Gentry and his Missourians to lead the assault.

Although it was winter, the notion of a Christmas celebration in the semitropical wilderness of central Florida was just a wistful idea. A bugler sounded the advance. His crisp, clear notes—a clarion call to action—rang out across the marshy expanse. Genry drew his sword and signaled his men to move forward. The attack quite quickly and literally bogged down. The Missourians sank into the viscous muck up to their waists. Despite the obstacle that the muck posed, Gentry showed no sign of stopping.

The painfully slow advance continued one step at a time. The men held their muskets and cartridge boxes over their heads to avoid getting their firearms and powder wet. The waters became tinted with blood even before the firing began, because the leaf edges of the fan-like sawgrass were serrated like a knife. The men suffered deep cuts on their arms, hands, and legs from just brief contact with the sawgrass.

The Missourians were about 50 yards from their objective when all hell broke loose. The hammock trees and shrubs erupted with gouts of smoke and flame, each burst representing a Seminole rifleman plying his deadly trade. The white soldiers could see the smoke, but not the shooters, who were well concealed. Seminole warriors wore colorful multihued shirts and turbans decorated with ostrich feathers, but the soldiers only glimpsed brief flashes of red, orange, or silver.

Gentry waved his sword, encouraging his men amidst the leaden storm, even though he had been wounded in the first volley. “Come on, boys, we’re almost there!” he shouted amidst the din of battle. “Charge on to the hammock!” But he was too conspicuous a target, and he received another bullet, this time in the abdomen. Gentry sunk down and did not rise again. But he was still alive; in a weak voice he shouted for his men to fight on.

Since Gentry had been in the front of the line, he was at a point well within range of the Seminole warriors. Sensing an opportunity for a prized scalp, several Seminoles emerged from cover to claim the prize. A group of Missourians, seeing what was about to happen, struggled to reach their wounded commander. There was brief hand-to-hand fight, and the Seminoles decided it was not worth pressing the issue, so they withdrew to the protection of their hammock. The bleeding colonel was taken to the rear, where he expired a few hours later.

The Missourian second-in-command, Captain Thomas Childs, sent a message back to Taylor, who commanded the reserve, requesting immediate support. “You must sustain yourselves,” Taylor tersely replied. Loud Seminole war cries were augmented by turkey bone whistles, enough to send frissons of fear down the spine of any enemy. Within a short time, Childs and the other officers were dead or wounded, and the Missourians, pressed to the limit of their endurance, began to waver.

The Missouri volunteers eventually broke. They retreated in a wild-eyed, confused, and unreasoning panic. For its part, the U.S. Army generally looked down upon volunteers and militia with undisguised contempt. After-action reports emphasized how most of the Missouri volunteers turned tail and could not be rallied and reformed. But more objective reports written at a later date indicated that many of the Missourians had continued to fight. The volunteers had performed their duty and maintained their muddy and miserable positions, according to these reports.

In any event, the well-trained U.S. Sixth Infantry went forward into the proverbial meat grinder, never flinching despite continued heavy Seminole fire. Bayonets gleaming, they marched with admirable discipline, displaying an almost parade-ground precision in spite of the spray of rifle balls that decimated their ranks and the viscous mud that made every step an agonizing experience. The regulars wore their military uniforms, of course, and this meant that they stood out in the wilderness more than the Missouri volunteers. The Seminoles made a point of trying to pick off the officers.

Lt. Col. Alexander Thompson was killed, as was his adjutant, Lieutenant J.P. Center, who was shot through the head. Although they were virtually leaderless at that point, the soldiers of the Sixth Infantry pressed on. In so doing, they sustained nearly 40 percent casualties. The Sixth began to fall back in an orderly fashion, but then stopped and began a new advance spearheaded by 160 men of the Fourth Infantry and a few volunteers. The Fourth managed to finally reach the hammock, where bloody hand-to-hand fighting ensued with the Seminole warriors in the dappled shadows of the pine trees. Soldiers wielding bayonets fought Seminoles swinging war clubs. The soldiers gradually began to push back the Seminole warriors.

But the Seminoles were conducting a fighting withdrawal, and never intended to take on Taylor in a pitched battle, a concept alien to their notion of war. Chiefs Sam Jones, Alligator, and Coacoochee accepted battle to allow women and children to escape. That mission accomplished; they were already in the process of withdrawing when the soldiers gained a foothold on the hammock.

The pace of their retreat picked up when Taylor sent his reserves to strike the enemy’s right flank. The warriors climbed into canoes and paddled away. This left Taylor’s army in possession of the battlefield, but their victory was a pyrrhic one. Taylor lost 25 killed and 112 wounded, while the Seminoles lost 11 killed and 14 wounded. After the battle, the spirit of the Seminole resistance was far from broken.

The American public was so desperate for a victory that Zachary Taylor was lauded as a national hero. His service in the Seminole War launched a political and military career that would eventually lead to the White House.

The Second Seminole War officially lasted until 1842. U.S. Army search-and-destroy missions prove extremely effective, tracking down cornfields hidden deep in the swamps and putting them to the torch. As a result, the Seminoles in hiding starved.

Starving and harassed by these patrols, many Seminoles surrendered and were shipped west. U.S. government officials also attempted bribery, and sometimes succeeded in their efforts. For example, the U.S. government gave Chief Coosa Tustenuggee $5,000. Still, a remnant of the tribe refused to surrender under any circumstances. Their Florida descendants still proudly live there to this day.

By the time the Seminole Wars had ended, they had become the longest Indian wars in U.S. history. The cost to the U.S. government was approximately $40 million, an astronomical figure for the time. It was a cost the nation could ill afford during an economic recession. The human toll was far greater. Approximately 300 U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps personnel were killed in action. As might be expected, the death toll from disease among U.S. military personnel fighting in the Florida swamps was even greater. It is estimated that 1,145 regulars and volunteer militia succumbed to a variety of tropic ills, including yellow fever.

For the Seminoles, the tragedy ran far deeper. Figures are lacking, but overall the Seminoles seem to have had far fewer casualties in actual battle than the whites. But war casualty figures, incomplete as they are, give scant justice to the hundreds of Seminoles, including women and children, who died of starvation in the swamps or of disease and hardship on their journeys into exile.