By Patrick J. Chaisson

Lucian Truscott needed a cigarette. The 47-year-old brigadier general was having the worst night of his life. Earlier that day, American troops under his command charged ashore on the Atlantic coast of French Morocco as part of Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa. From the start, though, almost nothing went right.

“As far as I could see along the beach there was chaos,” Truscott recalled. “Landing craft were beaching in the pounding surf, broaching to the waves, and spilling men and equipment into the water. Men wandered about aimlessly, hopelessly lost, calling to each other and for their units, swearing at each other and at nothing.”

Alone in the darkness, General Truscott “sought the comfort of tobacco” and lit a smoke. He was heartened to see the pinpoint glow of other cigarettes appearing along the beach, although Truscott later remarked how surprised his troops would be to learn their commanding general was the first man to disobey his own blackout order.

The flicker of cigarettes at night was but one of many problems facing Truscott and the 9,100 soldiers he

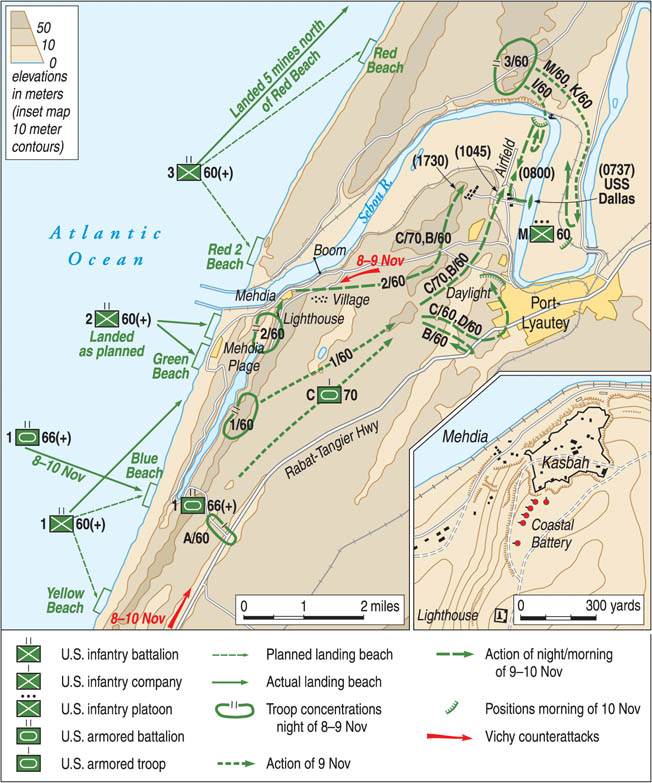

commanded. Put ashore by the U.S. Navy after dawn on Sunday, November 8, 1942, these assault troops had as their objective a military airport at Port Lyautey, French Morocco. Allied airmen needed this field, situated nine miles up the twisting Sebou River from the landing beaches on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, to cover the invasion. Truscott expected his men to seize it by noon on D-day.

Yet the Port Lyautey aerodrome would not fall to American troops for two days. A variety of factors contributed to this, most of which had to do with the near total inexperience of U.S. Army and Navy forces in the realities of amphibious combat. Landing barges came in late and far off course. Soldiers straggled during exhausting approach marches. Heavy surf and soft sand hampered beach operations, leaving the infantrymen ashore largely without tank, artillery, or medical support.

Worst was the French response to Truscott’s invasion. Instead of welcoming his men with brass bands, as one sergeant predicted, Vichy France’s colonial forces fought back with everything they had. French fighter planes attacked U.S. troops on the beachhead, while coast artillery guns dueled with American warships offshore. Allied soldiers could only watch helplessly as well-led French reinforcements rushed in from all directions.

Truscott was most concerned with his southern flank. There, U.S. infantry outposts had crumbled under an armored counterattack that threatened to annihilate the entire invasion force. Only the coming of night brought a halt to the enemy’s advance, which was sure to resume come morning.

Finishing his cigarette, Truscott considered what to do next. Then from out of the gloom came a man whom Truscott had been seeking all day. Lt. Col. Harry H. Semmes, one of the few combat-tested Americans ashore, dismounted from his M5 Stuart light tank and reported for duty. Truscott’s orders were simple: assemble your men, get into position by dawn, and stop the French counterattack.

Semmes saluted and set off on his mission. Only then did the World War I tank veteran ask himself how he was going to defeat 1,000 infantrymen and dozens of armored fighting vehicles with the seven M5s that had managed to land that night. Of this Semmes was sure—the approaching dawn would bring with it a momentous tank battle, one he would fight outnumbered against soldiers once regarded among America’s closest allies.

The struggle for Port Lyautey was part of a peculiar conflict fought between colonial French troops and Anglo-American forces from November 8-11, 1942. Allied planners labeled this campaign Operation Torch, while the

French called it la guerre des trois jours—the three-day war. Whatever its name, this massive expedition was easily the most ambitious, complicated endeavor of its kind yet attempted during World War II.

Torch originated in the strong desire of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to “open a second front” against the Axis powers. Reacting to pressure from the Soviet Union, then reeling from Nazi Germany’s seemingly unstoppable onslaught, Churchill and Roosevelt vowed to begin offensive operations against Hitler’s legions before the end of 1942. By doing so, they hoped to draw German troops away from the Eastern Front while demonstrating to Soviet Russia the Western Allies’ commitment to victory—a sentiment viewed with great suspicion by Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, whose Red Army had thus far done most of the war’s fighting and dying.

Although top political leaders were in agreement on the need for a second front, military officers within the British and American high commands clashed bitterly with one another over this campaign’s strategic scope and objectives. British planners envisioned an amphibious assault on North Africa to serve as a stepping-stone for follow-on invasions in southern Europe while simultaneously gaining control of the Mediterranean Sea. Their American counterparts were anxious to retake France and lobbied strenuously for a bold cross-Channel invasion, possibly as early as 1943.

President Roosevelt, mindful of his promise to Stalin, twice directed his Joint Chiefs of Staff to cooperate with British officers as they planned an Anglo-American invasion to occur somewhere in North Africa or the Middle East during 1942. Thus, rather reluctantly, the U.S. military began preparing for what would become Operation Torch.

Torch’s final plan called for simultaneous attacks on French Morocco and Algeria in northwestern Africa. Key objectives were the Algerian ports of Oran and Algiers on the Mediterranean Sea, as well as Casablanca along Morocco’s Atlantic coastline. Once established on land, Allied forces would head for Tunisia, 500 miles to the east, where they were to eventually link up with General Bernard Law Montgomery’s Eighth Army, then advancing through Libya.

A worldwide shipping shortage troubled Allied officers, as did the U-boat threat. The region’s geography also presented operational challenges. Any convoy passing the Straits of Gibraltar bound for landing beaches in Algeria would be threatened by Axis-leaning Spain. Worse, Nazi Germany might use an Allied offensive as a pretext to occupy the Spanish mainland or its colony in Spanish Morocco, closing the Straits and marooning Allied forces in their Mediterranean lodgments.

But the chief cause of Allied anxiety was France. With 109,000 servicemen in North Africa, bolstered by tanks, aircraft, and a modern surface fleet, the Vichy, or collaborationist, French military could greatly disrupt any Anglo-American landing attempt if it chose to fight. The Allies, then, had to prepare themselves for this contingency while holding out hope that these colonial forces would not resist an invasion.

Following France’s surrender in June 1940, Axis officials installed a puppet government located in the small resort town of Vichy. With World War I hero Field Marshal Henri Petain as its president, the Vichy regime ostensibly administered France’s overseas possessions as well as an unoccupied region on the French mainland known as the Free Zone. While tightly controlled by the Nazi regime, Vichy France was permitted the means to defend its African colonies against foreign invasion. Whether this meant invasion from Germany or the Allies, no one was yet sure.

Allied commanders especially feared well-armed and belligerent French naval forces based at the crucial port cities of Casablanca and Oran. Vichy warships there could decimate a landing attempt even while docked, so direct assaults against those harbors were ruled out. Instead, invading armies would have to land some distance away and maneuver cross-country to converge on their objectives.

For example, Maj. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Western Task Force needed to storm three widely separated beaches in order to surround Casablanca. Safi, 140 miles south of the city, possessed a harbor suitable for unloading medium tanks directly off their transport ships. Fédala, 12 miles north of Casablanca, was Patton’s main effort. His assault columns would then march on Casablanca and, with luck, seize its docks before French reinforcements could arrive. Seventy miles north of Fédala stood the all-weather runway at Port Lyautey, desperately needed by Allied air commanders to cover the invasion force. Patton knew all three operations had to succeed; the eyes of the world were upon him.

To take Safi Patton entrusted the 2nd Armored Division, an outfit he had recently commanded. Elements of the well-trained 3rd Infantry Division, fighting under Patton’s personal supervision, got Fédala. A reinforced regimental combat team (RCT) from the 9th Infantry Division, designated Sub-Task Force Goalpost, was identified for the Port Lyautey landings.

Goalpost required a general officer to command the 9,079 combat and service support personnel assigned to it. Accordingly, Truscott reported to Patton’s headquarters for this position in September 1942. A gravel-voiced Texan, Truscott’s last posting was as U.S. liaison to the British Combined Staff. He had witnessed the raid on Dieppe that August and also headed up a team that drafted the initial concept for Torch. Truscott, a career cavalryman, appeared perfectly suited to lead the Port Lyautey invasion.

Most of the soldiers earmarked for Sub-Task Force Goalpost were stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Truscott traveled there at the end of September to meet Colonel Frederick J. de Rohan of the 60th RCT, whose riflemen would form Goalpost’s backbone. Also present was Lt. Col. Harry Semmes, commanding the 1st Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment. Semmes had served with Patton’s tank corps during World War I, and when he learned no officer over the age of 50 would be allowed to deploy for Torch, went directly to his old boss pleading to be taken along.

“You can come,” Patton exclaimed after listening to Semmes’ appeal. “In fact, I’ll make you an armored landing team commander.” Semmes happily returned to his battalion and immediately began preparing it for the landings.

In camps across the United States and Great Britain, invasion forces gathered to ready themselves for this historic expedition. Troop lists were drawn up, training programs accelerated, and the myriad logistical details necessary for such an unprecedented transoceanic assault completed. It did not proceed smoothly. As historian Samuel Eliot Morison observed, “Preparations came to a close in the latter part of October in an atmosphere of unrelieved improvisation and haste.” These measures would have to suffice, as D-day was set for Sunday, November 8, 1942.

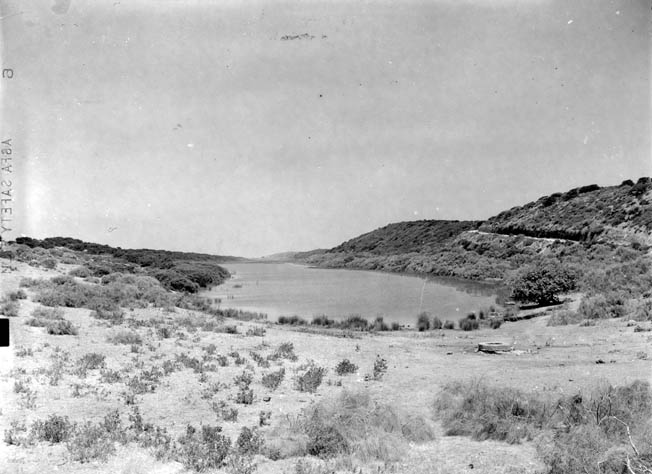

Issues of terrain bothered Goalpost’s planners. The Sebou River emptied into the Atlantic at a small resort village named Mehdia. Adjacent beaches permitted amphibious landings when surf conditions were right, although in November the ocean off Mehdia was notorious for its high tides. South of town, a lagoon stretching for almost four miles paralleled the shoreline. Attacking soldiers exiting north around the lagoon were channeled into a marshy gap; those heading south had to surmount an easily defended gorge before reaching the coast road to Rabat. North of the Sebou, trackless, scrub-covered ridgelines limited vehicular movement. The river itself could support ship traffic of up to 15-foot draft for the nine-mile journey to Port Lyautey and its airport.

All of these considerations plus the vital factors of weather, time, and tide, were evaluated by Truscott’s staff as it developed the invasion plan. It was a complex one. H-hour was set for 0400, two hours before sun up. The 60th RCT would land on five widely separated beaches along both sides of the Sebou, advancing rapidly inland to seize the airfield. The 54 tanks of Semmes’ armored battalion were to act as a reserve and exploitation force. To preserve surprise there would be no preparatory naval bombardment—all objectives were to be taken “with cold steel.”

Perhaps reflecting Truscott’s Dieppe experience, an old “four-stack” destroyer, the USS Dallas, would enter the Sebou at high tide and beach itself opposite the airfield. Then, 75 raider-trained infantrymen were to disembark and assault their objective under covering gunfire from Dallas. If all worked to plan, the field would be in American hands no later than 1100 hours and open to Army Air Forces Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter planes (carried aboard the escort carrier USS Chenango) later that afternoon.

Opposing the men of Sub-Task Force Goalpost in Port Lyautey were 3,080 colonial troops of the 1st Regiment of Tirraleurs Morocco, a light infantry formation largely equipped with Great War-vintage weapons. They were solid fighters, however, and ably led by a 48-year-old veteran named Colonel Jean Petit.

Petit’s riflemen were augmented by a group of nine modern antitank guns, three light tanks, an engineer company, and several batteries of artillery. Within six hours they could be reinforced by a regiment of 1,200 Spahis, horse and mechanized cavalry, stationed 90 miles inland at Meknès. More substantial support would come from the colonial capital of Rabat, 29 miles to the south. There, the 1st Regiment of Chasseurs d’Afrique stood ready with two battalions of truck-borne infantry, a squadron of armored cars, and 47 Renault tanks.

Other French forces were determined to hold Port Lyautey. From a bluff overlooking the mouth of the Sebou River loomed the Kasbah, a 16th-century Portuguese stone fort. Nearby were emplaced six modern 138.6mm coastal defense guns, each with a range of 12 miles. The entire plateau bristled with earthworks; 75mm howitzers crewed by the Légion Etrangère (French Foreign Legion) covered both the Kasbah and neighboring beach exits.

American commanders hoped their landings would go uncontested, but General Charles Noguès, commander of all military forces in French Morocco, had to resist for reasons of national survival. Noguès could not know whether Allied operations meant an all-out invasion or were merely a raid like Dieppe. If he surrendered to a raiding party not intent on holding Morocco, German retribution would be swift and violent. From Noguès’ headquarters in Rabat, through the regional command post of Maj. Gen. Maurice Mathenet in Meknès, down to Colonel Petit in Port Lyautey the message was clear: you will fight.

A silent procession of warships steamed toward the Moroccan coast during the night of November 7-8, 1942. This was the Northern Assault Group, commanded by Rear Admiral Monroe Kelly. The battleship USS Texas and light cruiser USS Savannah stood by to deliver naval gunfire support, while six destroyers and a pair of minesweepers helped shepherd the landing waves. Naval aircraft from the escort carrier USS Sangamon provided air cover and antisubmarine protection.

The invasion started poorly when several transports fell out of position off the landing areas. Due to a shortage of barges, it took time—too much time—for the assault waves to assemble and begin loading troops. General Truscott even shuttled from ship to ship, trying to speed the debarkation process. Returning at 0430 hours to his command post aboard the SS Henry T. Allen, Truscott was stunned to learn his communications officer had intercepted a radio broadcast from President Roosevelt asking the French not to oppose American landings in North Africa.

Sub-Task Force Goalpost had lost the element of surprise, upon which much of its plan depended. Faced with a number of unpleasant alternatives, Truscott decided to press on with a dawn assault. As the sky lightened over Morocco at 0540 hours, American troops stormed ashore.

It did not take long for the French to react. Naval observers first saw searchlights flash on, illuminating the landing craft. A red flare then shot up into the murk, followed by heavy small arms fire. Soon, coastal guns bracketed the destroyer Eberle; she returned fire and began evasive maneuvers. By 0630 hours, Savannah and the destroyer Roe were trading salvoes with Vichy coast artillery near the Kasbah.

At dawn a number of Dewoitine 520 fighter planes appeared over the invasion area, strafing several beaches and attacking one of Savannah’s spotter planes before Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters from the Sangamon chased them away. Navy bombers also worked over the Port Lyautey airfield, catching several Vichy planes on the ground. But the heaviest action was taking place on shore.

Following an unopposed assault on beaches south of the Sebou, Major John H. Dilley’s 2nd Battalion Landing Team (BLT) advanced to capture the Kasbah and its attendant coast artillery. The sound of shells passing overhead from Roe and Savannah disordered Dilley’s inexperienced battalion, however, and it sat paralyzed until those guns checked fire. French forces took this opportunity to rush reinforcements in from Port Lyautey; later that morning a Vichy counterattack led by three ancient Renault FT tanks almost drove the 2nd BLT into the ocean before it was blunted by Colonel de Rohan’s last infantry reserves.

There would be no help from the 3rd BLT, commanded by Lt. Col. John J. Toffey, landing to the north. This battalion was badly delivered five miles away from its designated beach and spent the entire day laboriously slogging over sand dunes while trying to gain proper positions. The raiding party aboard Dallas remained offshore as Vichy machine guns earlier drove off a scout boat whose mission was to cut an antishipping boom across the Sebou.

The men of Major P. DeWitt McCarley’s 1st BLT also landed far from their intended beaches. They made an exhausting foot march around the lagoon’s southern end, dropping off several platoons of Company A (accompanied by 37mm cannons of the battalion antitank platoon) to picket the coastal road. The remainder of McCarley’s outfit then maneuvered overland toward the airfield against stiffening opposition. Automatic weapons fire halted the 1st BLT at dusk, several miles from its objective.

The guns and matériel needed to overcome this unexpectedly fierce resistance were not getting ashore. As the day wore on the seas grew rougher. Dozens of landing craft foundered in the surf, too badly damaged for harried shore parties to repair. After enemy shells straddled his transport ships, Admiral Kelly had no choice but to move them out to a safer area 15 miles offshore—“halfway to Norfolk,” Truscott grumbled. The surviving barges now faced a 30-mile round-trip journey, further slowing the delivery of equipment and supplies.

Worse, the transports were now out of radio range. General Truscott had to find out what was going on, so at 1500 hours he went ashore. His jeep, like so many other vehicles on the beach, immediately became mired in heavy sand; Truscott was forced to borrow a half-track for his first tour around the battlefield. What he saw greatly discouraged him: infantry pinned down by a few machine guns, stragglers everywhere, supplies piled up on the beach with no apparent organization, and few leaders pushing their men forward.

Toward nightfall, dazed riflemen from McCarley’s Company A began filtering back with tales of strong enemy attacks along Goalpost’s southern flank. Earlier in the day, two U.S. infantry platoons had marched out to establish blocking positions along the coast road. Nothing had been heard from them since midafternoon, and now Company A’s commander was reported missing as well.

The advance guard of French chasseurs driving north from Rabat had swallowed these American outposts whole. Truck-borne infantry and armor overwhelmed a U.S. platoon at Sidi Bou Knadle, eight miles south of Mehdia, and then turned their weapons on 2nd Lt. Jesse Scott’s roadblock set up one mile away. Well-trained Moroccan riflemen supported by tanks made short work of Scott and his soldiers. Vichy forces then pushed against Company A’s main battle position, knocking out a 37mm antitank gun and capturing 2nd Lt. John Allers, the company commander. The French counterattack halted almost within sight of the beach, called off due to darkness and a line of American guns—dragged to the crest of a hill —that disabled two Renault tanks.

In the meantime, determined boat crews had managed to deliver seven M5 light tanks of Harry Semmes’ 3rd Armored Landing Team before rising surf closed the beaches. Semmes collected his tanks and before dawn moved out to a ridgeline marking Goalpost’s southern flank. Here he learned the radios and telescopic sights on all his Stuarts had come out of alignment during the journey overseas. Semmes’ tankers would have to fight much like their fathers did in World War I, using hand and arm signals while firing only at point-blank range.

On foot, Semmes guided his tanks into position along the ridge. A pair of M5s, commanded by Lieutenant John Mauney, covered the Rabat road from the west while the remaining five Stuarts, under Semmes’ control, sited themselves on the east side of the coast road. The American tankmen waited anxiously for daylight, certain a French attack was imminent.

The first streaks of dawn on November 9 revealed two battalions of Vichy infantry advancing from a white farmhouse a half mile away. Mauney’s tank section rode out to engage them. Deadly antipersonnel rounds and machine-gun fire from his two M5s nearly annihilated the lead company and so demoralized the rest that they never again offered serious resistance that day. But a bigger threat soon emerged from the edge of a cork forest to the east.

There, 14 two-man Renault R-35 tanks could be seen crawling forward against Semmes’ tiny force, firing armor-piercing rounds from their 37mm Puteaux cannons. Shell after shell struck Semmes’ Stuart. “I noticed there would be a shower of sparks when the front armor plate was hit,” he recalled. But, according to Semmes, instead of exploding “the white-hot hard steel core of the French shells ricocheted off … high into the air.”

Because their own guns were not boresighted, American tank crews had to hold fire until the Vichy armor grew dangerously close, 100 yards, to ensure hits. The M5’s 37mm was more powerful than its French counterpart, though, and U.S. shells easily punched through the Renaults’ plating. That was hardly the end of Harry Semmes’ troubles, however. He later wrote, “Because the weather was chilly, the mechanisms of the breeches of our American tank guns did not properly eject the empty shells when the guns were fired. All the loaders, who were also the tank commanders, lost their fingernails clawing out the shells after the guns had been fired.”

By backing into protected hull defilade positions while reloading, the Stuarts managed to keep their thicker frontal armor to the enemy and stay alive. But Semmes feared the advancing French tanks would soon flank his attenuated line. He soon received help from an unexpected source.

At daylight, the Savannah catapulted a pair of Curtiss SOC-3 Seagull spotter aircraft off its aft turret. These bi-wing floatplanes carried a crew of two and were armed with depth charges, a fixed forward-firing .30-caliber machine gun, and another .30-caliber on a flexible mount for rear defense. The SOC-3’s chief weapon, however, was its radio.

Flying low over the battlefield, one of Savannah’s Seagulls observed the desperate tank fight taking place between Semmes’ M5s and the Vichy Renaults. Radioing target data back to its mother ship, the vulnerable spotter plane then banked away to adjust fire. At 0750 hours, the first of 121 6-inch shells from Savannah’s main batteries began crashing in.

This shower of high explosives proved too much for the chasseurs. Pummeled by Savannah’s guns, all surviving R-35s began withdrawing into a nearby eucalyptus grove only to be savaged by a flight of low-flying Grumman TBF Avenger bombers from the Sangamon. Down on the battlefield, Semmes counted four destroyed Renaults—two of which his crew could claim. Semmes’ tank had been struck by eight Vichy shells, all of which failed to penetrate its steel hide.

General Truscott arrived in time to witness the battle’s aftermath. In the valley below, “a number of bodies were sprawled about in the various postures of sudden death,” he remembered. Harry Semmes described the fight his team had just won and requested reinforcements. An orbiting Seagull had just reported that the French were regrouping for another, larger attack.

It was not long before assistance arrived. Two half-track-mounted 75mm assault guns took up position toward the ocean, while 10 additional Stuarts extended Semmes’ line eastward into an adjacent cactus patch. These tanks belonged to Company C, 70th Tank Battalion, Captain William A. Edwards commanding, and were attached to Goalpost to provide infantry support. Instead, Edwards’ M5s would fight their first battle against enemy armor.

At 0900 hours the second Vichy assault began. One column of R-35 tanks moved up the valley while another infantry-armor formation attempted a flanking maneuver. They ran right into Company C, hidden among the cactus. Stuarts and Renaults played a deadly game of hide-and-seek. The tank commanded by 2nd Lt. Raymond Herbert had just killed an R-35 at point-blank range when it was hit in the side by French gunners. Herbert’s M5 burst into flames, badly wounding all four crewmen. Another Stuart was also destroyed in the fight.

Yet the Americans, aided by Savannah’s accurate gunnery, managed to hold. Tearing tank-sized craters in the ground, the cruiser’s 6-inch shells terrified the chasseurs and kept them from reorganizing. Her SOC-3 spotter planes got into the action too, even dropping 325-pound depth charges on Vichy targets. One of these projectiles exploded right next to a Renault, the concussion crushing everyone inside while leaving the tank’s hull intact.

When it was all over, Lt. Col. Semmes counted 27 burning R-35s and more than 100 dead French colonial soldiers sprawled in the fields below. American casualties totaled eight wounded. By 1430 hours the situation had stabilized, allowing Truscott to transfer Company C’s Stuarts for duty elsewhere. The rest of Semmes’ battalion, now with operational radios and gunsights, soon began arriving to help guard the invasion’s southern rim. While Vichy forces would make another halfhearted assault on November 10, U.S. tankers and the Savannah’s big guns quickly sent them scurrying back to Rabat.

The infantrymen of Sub-Task Force Goalpost could now focus on seizing their primary objective, the Port Lyautey aerodrome. Major McCarley’s 1st BLT, with Company C’s Stuarts in support, conducted an afternoon attack that wiped out 28 machine guns and four antitank guns. By sunrise on the 10th, they were ready to make one final push to the airfield. The 3rd BLT, converging from the north, stood ready to cross the Sebou River on rubber rafts once the signal was given.

But the Kasbah, now garrisoned by 250 diehard Vichy troops, refused to yield. Repeated American assaults on November 9 were easily repulsed. Feeling intense pressure to complete his mission, Truscott ordered Colonel de Rohan to personally lead a dawn attack the next day. The Americans were learning. Their early morning action started with two 105mm self-propelled howitzers blasting apart the Kasbah’s heavy wooden doors, followed by eight Navy Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers swooping down to plaster their targets with 500-pound bombs. Bayonet wielding infantrymen then rushed in, securing the Kasbah by 1050 hours.

While this assault was taking place, the USS Dallas proceeded up the Sebou River to run itself aground near the Port Lyautey airport. Dallas’ raiding party then went ashore via rubber boats to assist in capturing the airfield. By midmorning it was firmly in American hands—21/2 hours later, the first P-40s from Chenango began landing.

As darkness fell, U.S. troops could feel French resistance begin to fade. Telephone lines had already been humming for hours, carrying conversations between General Noguès in Rabat and Admiral François Darlan, the Vichy commander in North Africa, speaking from his Algiers headquarters. Sometime after 1930 hours Darlan issued a formal order declaring a suspension of hostilities. In Port Lyautey, Maj. Gen. Mathenet had taken command of Vichy forces. At 2330 he sent messengers to arrange a parley with Truscott the next morning.

At 0800 hours on November 11, the immaculately dressed French general passed through American lines under a flag of truce. Truscott, flanked by an honor guard of Harry Semmes’ tanks, met Mathenet at the Kasbah to direct terms for the cease-fire. After a final exchange of salutes, the two men took their leave of one another—no longer enemies but not yet allies. The battle for Port Lyautey was over.

The remains of 84 U.S. soldiers who lost their lives during this operation were laid to rest in a newly established military cemetery near the Kasbah. Another 11 sailors perished during the three-day fight, while 275 Americans were listed as wounded or missing. French casualties amounted to some 350 men killed, injured, or missing in action. In return for these losses, the Allies gained an air base sorely needed to keep critical sealanes open along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of Northwest Africa.

American commanders also acquired valuable experience in the intricate art of amphibious operations, skills they later put to good use at Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, and Normandy. Torch had been an initiation into the universe of combat for many U.S. fighting men, although their first taste of battle against the French left many officers and men with mixed feelings.

Truscott best expressed their doubts in his official report. “The combination of inexperienced landing crews, poor navigation, and desperate hurry resulting from lateness of hour,” he wrote, “finally turned the debarkation into a hit-or-miss affair that would have spelled disaster against a well-armed enemy intent upon resistance.”

The troops of Sub-Task Force Goalpost would experience that well-armed enemy soon enough. Even as Truscott’s soldiers were congratulating themselves on a successful invasion, battle-hardened German forces began pouring into neighboring Tunisia. Defeating those veterans would take months of tough combat, as well as the lives of many more Allied fighting men.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer, who during his military career held commands in armor, cavalry, and airborne units. He resides in Scotia, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments