by Jon Latimer

The battles of Kohima, Imphal, and the Admin Box saw the comprehensive defeat of the Japanese armies seeking to invade India during 1944 and sent them reeling back into Burma in early 1945, pursued by the revitalized British 14th Army under Lt. Gen. William Slim. The monsoon helped delay the Allies and enabled the new commander of the Japanese Burma Area Army, Lt. Gen. Kimura Heitaro, to redeploy for an organized defense.

Kimura planned to allow Slim to cross the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers and to fight in the area of Mandalay, believing this would bestow similar advantages of proximity to supplies enjoyed by the British at the start of the year. The British in turn would suffer the disadvantages of long, overstretched lines of communication.

Advancing on the Irrawaddy River, Slim ensured, however, that every administrative detail was attended to. Together with air superiority, this gave his forces an increasing advantage as the nature of the fighting altered with the changed conditions, now that they had come down from the mountains. Fighting in more open countryside also favored the British armor that completely outclassed and outnumbered Kimura’s solitary 14th Tank Regiment. In fact, Kimura’s plan made little sense in the light of either Slim’s or his own real circumstances, and Slim was not slow to take full advantage.

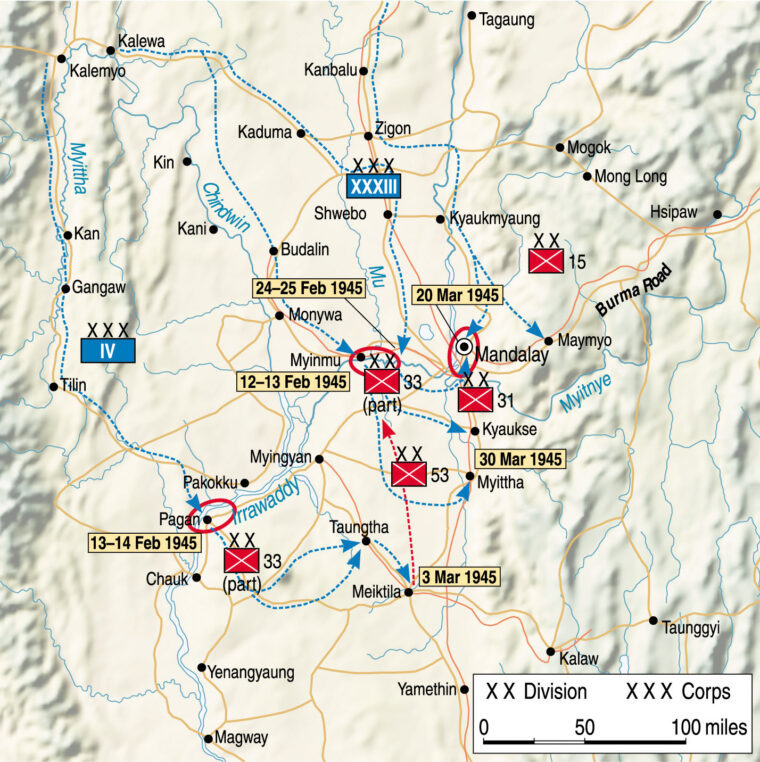

Slim conceived a cunning deception plan—Cloak—that he hoped would lead the Japanese to believe the whole of 14th Army was moving on Mandalay, while a force operating in the Myittha Valley was merely a diversion. This would in fact seize Meiktila and hold it as an anvil against which the rest of his force would act as a hammer to destroy the Japanese and prevent their withdrawal into Thailand.

Meiktila was identified as a crucial communications node a year earlier by Maj. Gen. Orde Wingate, leader of the famous Chindits. The bulk of the supplies for the Japanese 15th Army defending the Mandalay region and 33rd Army farther north passed through it. Slim believed that he could hold the town against counterattacks and that the combination of holding this key point and constant pressure elsewhere would lead to the total collapse of the Japanese.

Slim planned for the 19th Indian Division from XXXIII Corps to seize Singu, 60 miles to the north of Mandalay, through which a good all-weather road ran. This was to be followed by a crossing in the area of Myinmu 40 miles downstream to the west by the 20th Indian Division; then the British 2nd Division would make a maximum display of force to draw away enemy reserves. Shortly thereafter, Lt. Gen. Frank Messervy’s IV Corps would put the 7th Indian Division across as surreptitiously as possible near Nyaungu. Having secured a bridgehead, the 17th Indian Division (less one infantry brigade but reinforced by two armored battalions) would pass through and seize Meiktila by way of Taungtha. No attempt was to be made to hold the road behind open. The division’s third brigade would be air transported into Meiktila as soon as a landing strip could be secured.

The Desperate Japanese Attacks and ‘No Withdrawal’ Policy led to Enormous Casualties

To screen Messervy’s advance, the move would be preceded by either the Lushai Brigade or the 28th (East African) Brigade until the corps deployed, and the 255th Indian Tank Brigade would wait until called forward on transporters after the engineers had improved the roads. Radio silence was of paramount importance, and all communications had to be by landline or liaison officers. A dummy IV Corps headquarters would remain behind and transmit normal radio traffic. To further supplement this plan, Messervy devised a deception plan to cover his movement in the Myittha Valley and his intentions for crossing the Irrawaddy.

The buildup to the coup proceeded smoothly with the 19th Indian Division crossing on January 9, the 20th Indian Division on February 12, and the 2nd Division landing between them 12 days later. The Japanese launched repeated and desperate attacks at each of these bridgeheads, leading to enormous casualties in the face of the overwhelming fire support available to the British and Indian troops and forcing them back onto the defensive.

The Japanese then further compounded their losses with a policy of no withdrawal. The advancing Allies would drive the Japanese from their defensive positions in dawn-to-dusk fighting and retire into their own lines, leaving the Japanese to reoccupy their original bunkers. Then, the Japanese would be driven from them once more the following day in operations across now Familiar ground and at relatively little cost to the attackers.

The Japanese, recognizing that the principal cause of damage to them was the effective employment of Allied tanks, went to particular lengths to knock them out. At one point, an officer and a private scrambled out of the close scrub and clambered aboard a Lee tank of the 3rd Carabiniers fighting in support of the 2nd Division. The private was killed by machine-gun fire from another tank, but not before the officer had killed the tank commander with his sword, climbed into the tank as the body collapsed, and similarly killed the 37mm gunner before attacking the 37mm loader. The loader only survived by using the breech as cover and managed to fire six revolver rounds into his assailant, although it actually took a further three from another hastily recovered pistol to finish off the fight. All this time, the other four crew members were unaware of the carnage above them! The renowned fanaticism of the Japanese led merely to vast losses that they simply could not sustain.

The truly mortal blow to the Japanese Army in Burma fell on February 14, when the lead troops of the 7th Indian Division crossed the Irrawaddy near Nyaungu. Despite reports of their 300-mile approach march, Kimura refused to believe the scale of the threat developing on his flank, partly as a result of the deception plan and partly thanks to the aggressive use of armor in the northern bridgeheads. He knew there were only two Indian Army tank brigades operating in Burma and was convinced that both of these were being employed in the north. The vast length of the river line had meant that nowhere could it be defended in strength, as those facing XXXIII Corps had already discovered, and the opposition was patchy and sporadic at best.

The crossing of the Irrawaddy at Nyaungu was the longest opposed river crossing attempted in any theater of World War II, the river at this point being over 2,000 yards wide. Crossing in darkness, one company of the 2nd South Lancashire Regiment made it over, but two Japanese swimming in the river were shot by a sea reconnaissance unit, thus alerting the defenses. With daylight, the operation became singularly dangerous, and 2nd South Lancs suffered heavy casualties until the 4th/15th Punjab Regiment was able to land and clear the banks.

Meanwhile, a subsidiary crossing at Pagan by the 1st/11th Sikh Regiment made contact with an Indian National Army unit that wished to surrender. Carefully, aware of the prospects for treachery from their countrymen, the Sikhs took the position unopposed, and the bridgehead was rapidly consolidated. The defenders retired into catacombs at Nyaungu and refused to surrender. Consequently, the entrances were sealed with explosives.

As the buildup continued, the Japanese launched some air attacks but otherwise did little to interfere. The IV Corps had managed to hit the junction between 15th Army and 28th Army, and the Japanese were convinced that this new bridgehead was a diversion from the main effort taking place around Mandalay. It was a tribute to Messervy’s deception plan and to his drive and energy, willing as he was to take risks to get forward as quickly as possible.

Commanded by Maj. Gen. David “Punch” Cowan, the 17th Indian Division was to break out through the thin screen of Japanese covering the bridgehead. Cowan’s plan involved directing the 48th Indian Brigade supported by one tank battalion to secure the Pyinbin road junction and then seal off or capture Taungtha, while the rest of the 255th Indian Tank Brigade and the 63rd Indian Brigade bypassed to the south to take Mahlaing. The armor would secure Thabutkon airfield, and the 48th Indian Brigade would then abandon Taungtha, rejoining the rest of the division for the assault on Meiktila.

Soldiers Strapped Explosives to Their Bodies and Attempted Suicide Attacks on Tanks

On February 19, the reconnaissance column reported Pyinbin clear, and Cowan moved at once. The advance was along parallel axes with the 63rd Indian Brigade on the right led by the Sherman tanks of Probyn’s Horse and the 48th Indian Brigade on the left led by the Royal Deccan Horse. Flank protection was provided by the armored cars of Prince Albert Victor’s Own Cavalry and the16th Light Cavalry. At Oyin, the 63rd Indian Brigade discovered that the enemy were yet prepared to die to defend their position, even though they were from an administrative unit. They strapped explosives to their bodies and attempted to make suicide attacks on the tanks, although only one had any success.

Taungtha was occupied on February 24, and the undefended airfield at Thabutkon, 15 miles north of Meiktila, was captured by the 48th Indian Brigade on February 26. It was quickly brought into service for a stream of C-47 Dakota transports from U.S. 1st Air Commando Group to land the division’s remaining brigade, the 99th, and enable Cowan to attend to the capture of the town at full strength. This was a doubly important development since, by now, the Japanese had reoccupied Taungtha and the whole formation was dependent on resupply by air. By nightfall of February 27, the 9th Border Regiment, together with the Sherman tanks of Probyn’s Horse, was just six miles from Meiktila.

The threat should have been apparent to the Japanese by now, but a signal sent a few days earlier detailing the breakout had been corrupted so that instead of reading 2,000 vehicles it read only 200, and Kimura dismissed it as no more than a raid. A detailed investigation by historian Takuo Isobe has since cast an interesting light on this signal. The concentration of the 17th Indian Division and 255th Indian Tank Brigade was observed from a hill by two staff officers, one from the 33rd Division and the other from 15th Army, who agreed that 200 tanks were present plus 2,000 wheeled vehicles.

This was reported back to 15th Army, which passed it on to Burma Area Army in Rangoon with the recommendation that everything should be thrown into the defense of Meiktila. The fact that the coded message arrived in its correct form is not in doubt, but given the variance of the information from that of the intelligence section’s current assessment of the Allied armor’s location, it must have been changed before being passed on to Kimura. Burma Area Army had instructed 15th Army not to overestimate the enemy’s strength in the Meiktila area.

Whatever the frame of mind at headquarters, the local commander, Maj. Gen. Kasuya was convinced that he was about to be attacked in strength and began to prepare accordingly. He had available two airfield battalions, a reinforcement battalion, and a number of administrative units plus the 168th Infantry Regiment en route to rejoin its division in the Burma Area Army. His force totaled about 3,500 men. Cowan ordered his division to commence the general attack on Meiktila on March 1.

Leaving the 99th Indian Brigade to hold Thabutkon, Cowan deployed his division to strike the town from the north and west. The 63rd Indian Brigade advanced through an area of scattered buildings and dense thickets from the west to clear its section in two attacks, each made by a battalion supported by tanks. The 48th Indian Brigade’s objective led it through the heart of the town, where it faced mines, mortars, and accurate artillery fire, which slowed it down.

Accompanied by two battalions of infantry riding in trucks, the 255th Indian Tank Brigade had skirted to the eastern side to clear the satellite airstrip at Thedaw and found it held by a well-concealed and dug-in force. When the 48th Indian Brigade finished clearing its section on March 3, the remnants of the garrison tried to break out toward the east but were intercepted and destroyed by the infantry.

For three days, the Allies had fought steadily through the streets until they had practically annihilated the defenders, some of whom even sat in holes in the ground with 250-pound bombs between their knees, waiting to detonate them by bashing the primer with a stone as a tank passed overhead. Fortunately for the attackers, by this stage of the war the skill of the Japanese seldom matched their courage.

Faced with a disastrous situation as a result of the loss of Meiktila, and with his forces largely pinned down around the country, Kimura was left with little option but to abandon northern Burma and the Burma Road that enabled supplies to be transported from India to China. He was also compelled to bring the 33rd Army, under Lt. Gen. Masaki Honda, south to take over efforts to clear their lines. For this, he would command the 18th and 49th Divisions, elements of the 53rd Division, and the 14th Tank Regiment.

Due to a severe shortage of transport, these formations only arrived in the Meiktila area piecemeal, and it was not until March 15 that Cowan was aware that they came under a single command. Indeed, their communications arrangements meant that coordination was so difficult that they effectively operated independently. When the 14th Tank Regiment attempted a road move in daylight, it was caught by Allied fighter-bombers and two thirds of its strength was left wrecked and burning on the route. Only six Type 97 tanks arrived in the operational area, where they were employed as mobile pillboxes.

Thus began what became known as the “Second Siege,” with the 17th Indian Division isolated far behind enemy lines. Slim now held the initiative, and the morale of his men had never been higher. He decided to put the 5th Indian Division under Messervy’s control, knowing that, although this left him without a reserve, the critical point of the campaign had been reached. All the troops in the 14th Army were now heavily engaged in their respective battles with the enemy to their front, but all were working toward the same goal: the strangulation of the Japanese through the chokepoint of Meiktila.

“The Wood was Suddenly Alive with Small-Arms Fire, Rifle and Automatic.”

Despite being nominally under siege, it was not Cowan’s men who were struggling under the circumstances. Cowan intended to retain the initiative with a series of aggressive sweeps. Using the town as a large patrol base, armored cars were sent ranging far and wide in search of the enemy, which was attacked wherever found by columns of armor and infantry, well supported by artillery and aircraft.

Commencing on March 6, five columns were sent out in different directions, only one of which encountered resistance near Thedaw airstrip. After being hit by air strikes, the Japanese tried to get away but were cornered and destroyed. A second series of raids was dispatched.

A young soldier in the 9th Border, George MacDonald Fraser (later author of the Flashman novels), described a typical action: “I fetched up at the tree, its trunk between me and the bunker, Stanley ran forward, firing from the hip at the firing-slit. Dust flew from the bunker as the Bren burst hit it … then I was diving down beside the bunker wall, about a yard to the side of the firing slit, fumbling for a grenade. I was facing back the way we had come and there were dark bush-hatted figures running through the trees, and the wood was suddenly alive with small-arms fire, rifle and automatic.”

According to the official history, over the two days of that operation, the 9th Border lost 141 casualties and one of its supporting tanks. Fraser recalled, “That tank burned for hours.” Eventually, the Japanese 18th Division was forced to abandon its entire section of the perimeter.

That tank was one of few the Japanese succeeded in destroying in what was essentially a one-sided struggle, given the almost complete lack of antitank weapons available to them. A third series of raids was dispatched on March 13, and Cowan likened these moves to a boxer using straight lefts to keep his opponent from closing effectively. But he did not have it all his own way, and two of these latter columns met with disaster.

Although the Japanese had been able to reoccupy Taungtha and cut the 17th Indian Division off from the bridgehead at the river, this did not last long. On March 12, troops from the 7th Indian Division overwhelmed them. Nevertheless, it was apparent that the Japanese were closing in on the town. By March 15, it was obvious that they had lost interest in Mandalay, and the whole character of the operations in both areas changed. Pressure was building steadily on Meiktila, and a strong column of the 20th Indian Division was dispatched to make contact with the 17th. By the middle of March, IV Corps, now reinforced with the 5th Indian Division, was tightening its grip on the Japanese communications with Rangoon, and Slim was ready to make good his plan to trap and destroy Kimura.

Honda was presented with a very gloomy picture on taking over preparations for the recapture of Meiktila. The enemy was so abundantly supplied from the air that it would be necessary to concentrate attacks on the airfields and supply lines, and he set about regrouping 33rd Army to do this. His report to Kimura stated bluntly that the outcome of this action would decide the fate of the Japanese forces in Burma.

During the night of March 14, the Japanese began their offensive against the airfield. Although they achieved little success to begin with, they did manage to get close enough to it to bring down fire that was to prove hazardous for the reinforcements arriving the following morning in the form of the 9th Indian Brigade from the 5th Indian Division. While the fire caused no serious damage, it was apparent that it would not be possible to bring in the rest until the 99th Indian Brigade, responsible for airfield security, had cleared it. Patrols discovered that a strong enemy force had dug in on the eastern side of the runway, and the 16th was spent clearing it away. The following day, the remainder of the 9th Indian Brigade was brought in. However, the Japanese redoubled their efforts to close the airfield on the 17th, and all future supplies had to be air-dropped.

At the same time, Cowan was ready to begin a general offensive against the enemy forces closing in on Meiktila with the aim of destroying them. The 9th Indian Brigade was detailed to hold the airfield perimeter and spent the next few days constantly patrolling to seek out and eliminate the snipers, artillery, and enemy patrols that were constantly filtering into the area. Pressure was also beginning to grow from the south and southeast held by the 48th Indian Brigade, and it became obvious that the enemy intended to launch an attack from this direction.

Columns were sent out from both brigades, and on March 22, the 48th Indian Brigade lost three tanks. The Japanese followed and deployed one gun within 15 yards of an outpost held by the 1st/7th Gurkha Rifles. The threat from this area prompted Cowan to send the 99th Indian Brigade in a sweep that, combined with the 63rd Indian Brigade working from the north and northwest, finally cleared the enemy out and made possible a link with the 5th Indian Division.

Barely 50,000 of the 260,000 Japanese Troops Survived Long Enough to Surrender

The pressure continued at the airfield until March 26. Once more, it was grim, close quarter stuff. As darkness fell on March 24, a Japanese tank drove unmolested along the runway. Only after it had been joined by two more and some infantry and attacked a post of the 3rd/2nd Punjab Regiment was its nationality determined. After a desperate fight, it was driven off. Parties of the enemy repeatedly dug themselves in within the perimeter and succeeded in destroying a number of aircraft.

As all this was taking place, Messervy was finishing his plans for the final stage of the battle and the advance to Rangoon. By the 25th, the 5th Indian Division was ready to attack from Taungtha and cleared a number of strongpoints covering the town from the north. A hill dominating the approaches, Point 1788, had been surrounded, and most of its outlying posts mopped up when on March 29, after an accurate airstrike, it was finally occupied without further struggle. The 17th Indian Division had by now reoccupied Mahlaing, and the 5th Indian Division was clear to enter Meiktila. All traces of the enemy had evaporated, and the Second Siege was over.

The Japanese 15th Army had been unable to contain the pressure building up against it from XXXIII Corps around Mandalay. Deprived of ammunition and sustenance, it had simply fallen apart. The city had fallen on March 20, and the withdrawal had to be routed well to the east of Meiktila. Honda told his men to abandon their attempts to recapture the town and restablish a defense line at Pyawbwe.

Kimura’s Army Group had been effectively smashed, although this meant that thousands of Japanese troops were still in central Burma. Despite their disruption and fragmentation, they still posed a significant threat and were capable of considerable resistance, particularly given their fanatical will to die rather than surrender. Slim was determined that they must not be allowed to regroup. Rangoon lay over 300 miles to the south, and the monsoon was rapidly approaching, but it could be reached and a coup de grace inflicted if further risks were taken.

This was immediately set in motion, and using a policy of bypassing centers of resistance, an advance of 10 to 12 miles per day could be maintained. The success with which this was achieved gave the Japanese no time to reorganize and offer a coordinated defense at Pyawbwe. A mixed mechanized force of brigade strength turned the Japanese western flank before wheeling north and destroying supply dumps that Honda had only managed to accumulate with great effort.

On April 11, Cowan’s men led the corps in overwhelming the main position, and Honda narrowly managed to evade his pursuers as they streamed southward. With XXXIII Corps charging down a parallel axis, IV Corps brushed aside the opposition until April 27 when it reached Payagale, where it met a strong defensive position prepared by engineers and comparable to the defenses at Meiktila. After a hard fight, it was cleared by 1700 hours, reducing the day’s advance to six miles. In spite of this, a recon squadron that had bypassed the position ambushed a convoy, including a number of staff vehicles, confirming that the enemy was evacuating Rangoon and retreating into lower Burma.

With time running out before the monsoon, the speed was increased, but having covered 300 miles in three weeks the pursuit was brought to a close 32 miles short of the goal when the weather broke. The enormous disappointment of failing to snatch the prize at the last hurdle was, however, tempered by the surprising news that Rangoon was in British hands. The XV Corps, which had been operating on the coastal flank, had been ordered to mount an amphibious landing in the mouth of the Rangoon River to catch the Japanese in the maw of a trap. On May 1, a battalion of the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade had been dropped at Elephant Point, followed by the landing of the 26th Indian Division. The city was swiftly occupied without opposition.

What was left of Burma Area Army tried to escape into Thailand. It took until July to eliminate the last remaining units, and then a hunt for the stragglers took place as they tried to flee across the border. When Japan surrendered in August, barely 50,000 of the 260,000 troops present in Burma at the beginning of the year were left to lay down their arms.

Jon Latimer is the author of several books on World War II. His most recent work is Burma: The Forgotten War. He lives, writes, and teaches in Great Britain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments