By Eric Niderost

In June 24, 1867, W.W. Wright’s survey expedition reached Fort Wallace, Kans., one of the string of military posts that guarded the Smoky Hill Trail to Denver and the beckoning goldfields of Colorado. The Union Pacific-Eastern Division (later Kansas Pacific) was beset by a host of problems, not the least of which was a growing hostility by the native Indian tribes that inhabited the area. The company directors dispatched Wright to conduct a survey to determine the best route to the western ocean.

Indian attacks all along the Smoky Hill River region meant the Wright expedition needed a military escort. Captain Albert Barnitz’s Company G, Seventh Cavalry, was assigned escort duty, and the first stages of the trip proceeded without incident. Barnitz was pleased by his first look at the fledgling post, a sentiment shared by newspaperman A.R. Calhoun, who wrote, “In the bright sunlight Fort Wallace looked like a beautiful little village.”

Some of the fort’s “magical” qualities were based on distance, only to evaporate like a shimmering mirage when the saddle-sore travelers drew closer. Fort Wallace was still under construction, but since the soldiers themselves were doing the building, progress was by fits and starts. Every time the alarm was raised, construction ground to a halt while sweat-soaked soldiers traded saws and hammers for Spencer carbines.

The Indian War of 1867 has its roots in the surge of westward development that followed the years just after the Civil War. Now that the fratricidal bloodletting was over, the nation bound up its wounds and looked to the West. Railroad building was both a symptom of this new westward expansion and its chief beneficiary. Government subsidies financed the Union Pacific and the Union Pacific-Eastern Division as they lay ribbons of steel across once-pristine prairies.

The Plains Indians looked on such activities with undisguised alarm. To them the railroads were not the standard bearers of civilization, but invaders extinguishing a traditional way of life. The Plains tribes were nomadic hunters who depended on the great buffalo herds to survive. White hunters slaughtered buffalo to feed construction crews, while trail traffic and military posts scared off the dwindling herds.

Faced with the complete destruction of their way of life, Indian tribes felt justified in fighting back. White attitudes added fuel to the volatile mix. Most whites considered Indians little more than savages. Not all Indians wanted war, but opinions within tribes were divided. At the root of the conflict was a terrible dilemma founded on an impossible choice. The U.S. government basically wanted the Indians to completely abandon their languages, religions, and traditional ways of life. If they continued to resist, there was the possibility of complete extermination in war.

The Indian tribes thus had two choices: cultural extinction or physical extinction. It was a terrible dilemma, because their culture was their life. Passions were further inflamed when a peaceful Cheyenne village was attacked by Colorado militia in the infamous Sand Creek massacre of 1864. Word of the terrible massacre at the hands of whites sparked a new round of Indian raids.

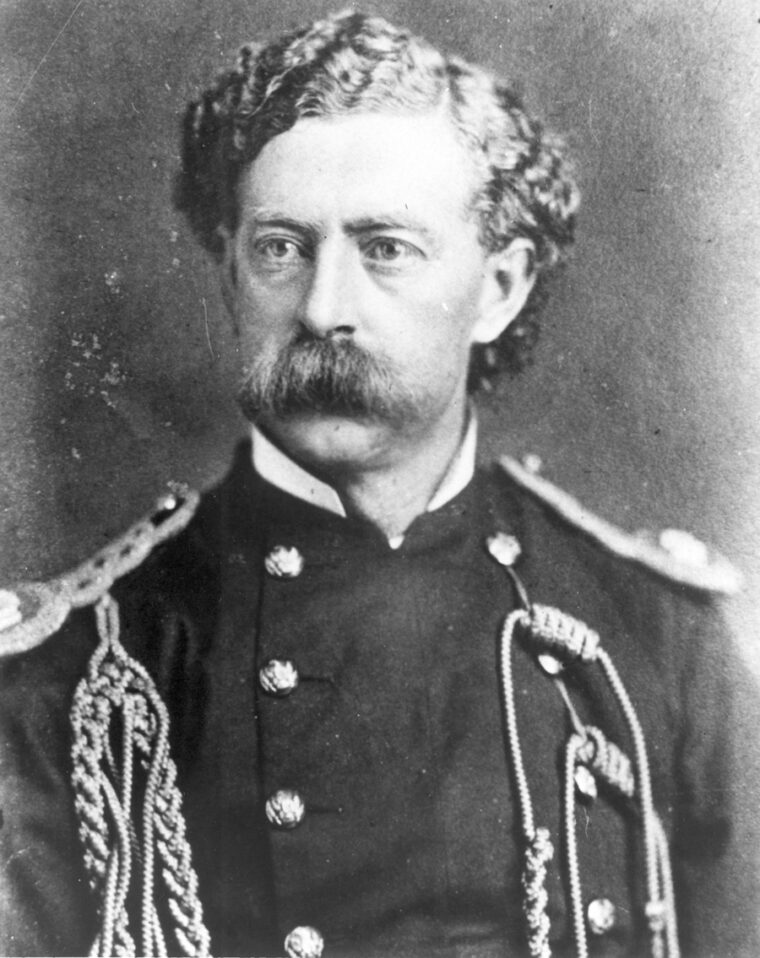

In the spring of 1867 Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock was ordered to mount an expedition to pacify the Plains once and for all. Hancock was a handsome man whose soldierly bearing and well-trimmed imperial mustache and goatee were everyone’s image of a general. And there was substance behind the image—he had chalked up a brilliant Civil War record as a Union Corps commander.

But Hancock had a terrible flaw—he was a thoroughly conventional general trying to fight an unconventional war. Indians were not southern Confederates, yet at times Hancock didn’t seem to know the difference. He was told not to approach a large Cheyenne village at Pawnee Fork, since the Indians feared another Sand Creek. He ignored the advice of Indian agent “Ned” Wyncoop and marched to the village anyway.

When some stagecoach personnel were killed by Indians along the Smoky Hill Trail, Hancock didn’t bother to distinguish the innocent from the guilty. The general ordered the now-abandoned village put to the torch, which meant hundreds of Indian families lost all their possessions. It was a “salutary” lesson often used in the Civil War, but if it was meant to cow the Indians, it had precisely the opposite effect.

Hancock also had a negative impact on Fort Wallace. When the general arrived at the fort on June 16 he decided to enlarge his escort. Post commander Captain Miles W. Keogh and 40 members of his Company I, Seventh Cavalry were ordered to accompany Hancock to Denver. (When Keogh died at the Little Big Horn nine years later, his gelding mount “Comanche” would be celebrated as the “last survivor” of Custer’s ill-fated command.) The subtraction of Keogh and 40 troopers reduced the Fort Wallace garrison to a dangerous level, because many soldiers were absent on escort duty or guarding stage stations along the Smoky Hill Trail. Before Barnitz and his Company G arrived, there had been less than 50 men at the post.

Barnitz noted in a letter to his wife Jennie that Fort Wallace was “situated on high ground about a mile distant from the south fork of the Smoky [River].” Much of the building material came from a quarry about three miles away. The captain noted that the stone was multihued, mostly yellowish but also tinged and sprinkled with red and brown. Of course, the average soldier didn’t care much for such aesthetics, but did appreciate the fact that the material was soft and easy to cut from the living rock.

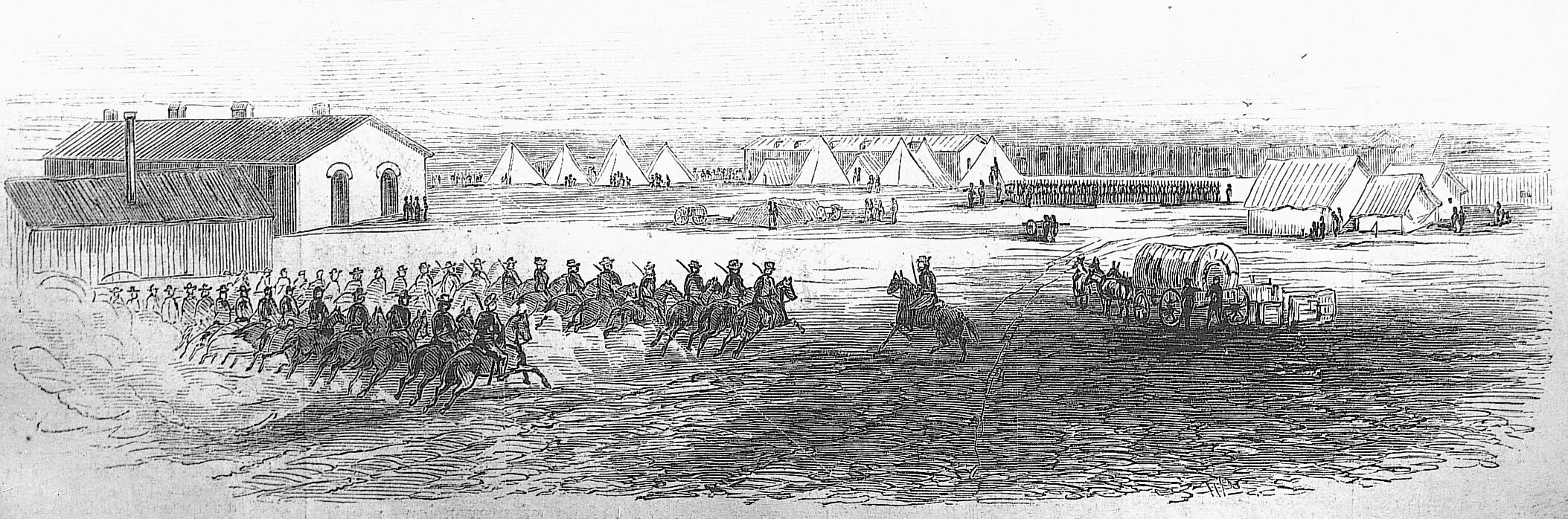

In June 1867 Fort Wallace was very much a work in progress. The sutler’s store, commissary building, and a company barracks were complete, fine, handsome structures sturdily built of local stone. Other parts of the fort were makeshift, shabby, and downright uncomfortable. The officers lived in tents that mushroomed around the buildings in neat rows.

To the casual observer the surrounding prairie seemed benign, but appearances were deceiving. The grasslands stretched to some high bluffs about five miles from the post, craggy sentinels brought out in high relief against the cloud-bedecked Kansas sky. Occasionally some pronghorn antelope might been seen grazing, ever alert for prowling wolves, but for the most part the prairie seemed unthreatening.

In reality Fort Wallace was under a kind of siege. One of the military’s main missions was to keep the lines of communication open between Denver and points east. Freight wagons carried cargo and stagecoaches carried mail and passengers vital to the region’s future development, but in recent weeks growing Indian attacks up and down the Smoky Hill Trail forced the Overland Stage Company to virtually suspend operations.

Stage stations had been placed at 12-mile intervals, places where fresh teams replaced worn horses and a passenger could get a rough meal and some respite from his bone-jarring journey. But lately the stage stations had been targeted by roaming war parties of Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho. Livestock was run off, employees killed and scalped, stations put to the torch. Sometimes the stagecoaches themselves were attacked, even though they usually had an Army escort. On June 15, 1867, two westbound coaches were forced to backtrack and return to Fort Wallace after being set upon by two to three hundred warriors. In the running fight Privates Edward McNally and Joseph Waldroff, U.S. Third Infantry, were killed.

On June 21, hard-riding Cheyenne warriors appeared at the fort, setting upon some quarry teams, killing a civilian driver, and sparking a fight that lasted several hours. First Lieutenant James Bell of Company I soon sent them packing, but at the cost of two killed and one wounded. The next two or three days seemed like an eternity to the tiny garrison, whose men scarcely slept a wink. Eyes red-rimmed from lack of sleep, beard stubble darkening haggard cheeks, the blue-clad men wearily greeted the Wright Survey party when they rode in on the 24th.

That same evening 20 mule-drawn Army wagons rattled into the fort, sent by Seventh Cavalry field commander Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer to pick up much-needed supplies. The supply train was guarded by Company D, Seventh Cavalry, and jointly commanded by Lieutenants Samuel Robbins and William W. Cooke.

The supply train’s sudden appearance was mystifying; this was definitely an unscheduled stop. Lieutenant Cooke, a distinguished man who sported long, trailing “Dundreary” whiskers, asked if Custer’s wife Elizabeth was at the post. He seemed a little disappointed when told she wasn’t there. Cooke had a letter to deliver, but more importantly he was to take her back with him when the supply train was ready to make the return trip. Robbins and Cooke explained that Custer was about 180 miles northeast of Fort Wallace, scouting the forks of the Republican River for any sign of hostiles.

Although Barnitz and the others didn’t know it, the ever-impetuous Custer was deliberately disobeying orders by sending his supply train to Fort Wallace. His superior, General William Tecumseh Sherman, wanted him to draw provisions from Fort Sedgwick in Colorado Territory. Supplying Fort Wallace was a logistical nightmare, but Sedgwick was linked to eastern depots by the Union Pacific Railroad. Sherman also wanted Custer to “show the flag” along the Platte River, serving notice to any hostile Indians that attacking the white man’s “iron horse” would be decidedly unwise.

Custer ignored Sherman’s directives and sent the supply train to Fort Wallace anyway. He tried to justify his actions, but the excuses he advanced did not ring true. In this case it was a question of personal desires being more important than military concerns—the flamboyant Custer was letting his heart rule his head. Nothing was more important to him than being reunited with Libbie and having her in his arms. Although the need for supplies was legitimate, it was also an elaborate “cover” to pick up Libbie and take her back to her lovelorn husband.

On the morning of Wednesday, June 26, Dr. William A. Bell set up his photographic equipment in preparation to make some prints. Photography wasn’t exactly easy in this era; it took time to coat, sensitize, expose, and develop glass-plate negatives. It wasn’t a job for amateurs, yet paradoxically, that’s just what Bell was—an amateur. He was an aristocratic English physician far from the luxurious drawing rooms of his native London. But when he heard the Wright expedition needed a photographer, he jumped at the chance—here was a way to explore the wonders of the West.

Bell found a kindred spirit in the person of Sergeant Frederick Wyllyams, Company G, Seventh Cavalry. The U.S. Army was often a refuge in the late 19th century, serving the same purpose as the French Foreign Legion at a later time. Wyllyams was educated at Eton, and was every bit the British gentleman as Dr. Bell. But some youthful indiscretions—probably involving a woman—had forced Wyllyams to immigrate to America to avoid a full-blown Victorian scandal. As soon as his duties permitted, Wyllyams told Bell, he wanted to assist the doctor in making some prints.

That same morning Albert Barnitz rose early, carefully stuffing his sky-blue trouser legs into his cavalry boots then slipping on his dark blue officer’s coat with the yellow shoulder straps that proclaimed him a captain of cavalry. Easing a dark slouch hat onto his head, Barnitz headed over to the commissary to eat breakfast.

A poet in his youth, he was an iconoclast who rebelled against Victorian mores and retained a large dose of skepticism about religion. A good officer, he was conscientious and utterly devoted to duty. He was no teetotaler, but Barnitz was free of the alcoholism that plagued the Army in this period.

Before Barnitz could have breakfast the alarm was raised, transforming a once-peaceful camp into a hive of frantic activity. Soldiers hurried about, some diving into tents to retrieve sabers or guns. Barnitz quickly discovered the source of the commotion—a large force of Indians was raiding the Pond’s Creek stage station, trying to run off company mules and horses corralled there.

Barnitz issued a flurry of orders to meet the impending crisis. Horses were to be gathered and saddled as quickly as circumstances would permit. First Sergeant Francis S. Gordon was directed to form the company for action, while Barnitz went ahead to reconnoiter. Gordon was one of the best noncommissioned officers in the Seventh, dependable and trustworthy. In Barnitz’s absence he could be counted on to obey orders with a degree of efficiency and dispatch.

In the meantime, the captain rode out to some high ground just to the northwest of the fort accompanied by Trumpeter Edward Botzer. Sweeping the horizon with his glass, he saw small knots of mounted Indians to the west and north. Rising dust clouds from the direction of Pond’s Creek station confirmed the accuracy of the first alarm—stock was certainly being driven off. Sergeant Gordon and G Company came up at the gallop, joined by some members of I Company who still remained at Wallace. Altogether Barnitz had 49 men under his command—39 from his own company and 10 from Keogh’s I Company.

Barnitz knew he had to act fast, yet be prepared for the unexpected. The Indians were usually unpredictable—they might decide to stand and fight, or they might scatter to the four winds. Within a few minutes the captain had formulated a battle plan. When Sergeant Francis Gordon galloped up with G Company, Barnitz divided the command into two platoons. Gordon’s first platoon was to move toward the northwest, where most of the warriors seemed to be clustered. Slightly amending his instructions, Barnitz told Gordon to bear slightly to the left in his advance, to cut off a party of Indians splintering off from the main group.

Sergeant William Hamlin of Company I was instructed to attach himself to Gordon’s skirmishers. A second platoon under Quartermaster Sergeant Josiah Haines was to form a second line about 200 paces behind the first “skirmishing” platoon. The troopers formed themselves with scarcely a pause and moved forward at the gallop. Their basic weapon was the Spencer carbine, a repeater that held seven shots in a spring-loaded tube concealed in the butt. For close fighting many troopers preferred the time-honored saber, which prompted the Indians to dub cavalrymen “long knives.”

The two lines of blue-clad troopers made a grand show, horses straining at the bit, hooves producing a thunderous tattoo that kicked up clods of dirt and produced plumes of dust in their wake. The Indians just ahead seemed unimpressed by the martial display and made no move to retreat. It was obvious they had decided to fight, not run. The Seventh Cavalry had been formed only a year before at Fort Riley, and the coming fight would be the regiment’s first major combat.

Many warriors were dressed in their finest regalia—if killed, they would meet the Great Medicine, the power that created all life, in proper fashion. Muscled torsos were bare, though a variety of necklaces were worn. Faces were daubed in multicolored war paint so nightmarish Barnitz conceded they were “hideous.” Some warriors wore the distinctive feathered trail bonnet that has since become the emblem of all Indians.

Above all, the Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors were well armed with a variety of weapons that ran the gamut from traditional to modern. It was all a matter of an individual warrior’s taste or whim. Some were armed with bows and arrows, others with lances decorated with a fringe of eagle feathers. Many had repeating rifles—the Henry repeater was one popular type—and virtually all carried pistols.

As the bluecoats advanced the tempo increased, but suddenly Gordon’s horse stepped into a prairie dog hole. Horse and rider tumbled to the ground; Gordon was propelled forward by the sheer momentum of his mount’s forward motion. He collided heavily with the earth, the impact knocking the wind out of him and leaving him bruised and dazed.

His mount quickly recovered, regained his legs, then bolted forward, leaving his master far behind. Barnitz saw what happened and rushed forward to try to capture Gordon’s stampeding mount. This was more than just an act of kindness for an unhorsed trooper, because Gordon’s presence was vital if the battle plan was to be brought to a successful conclusion. The captain just managed to seize the reins, and once the animal calmed down a trooper was delegated to return the wayward horse to its owner.

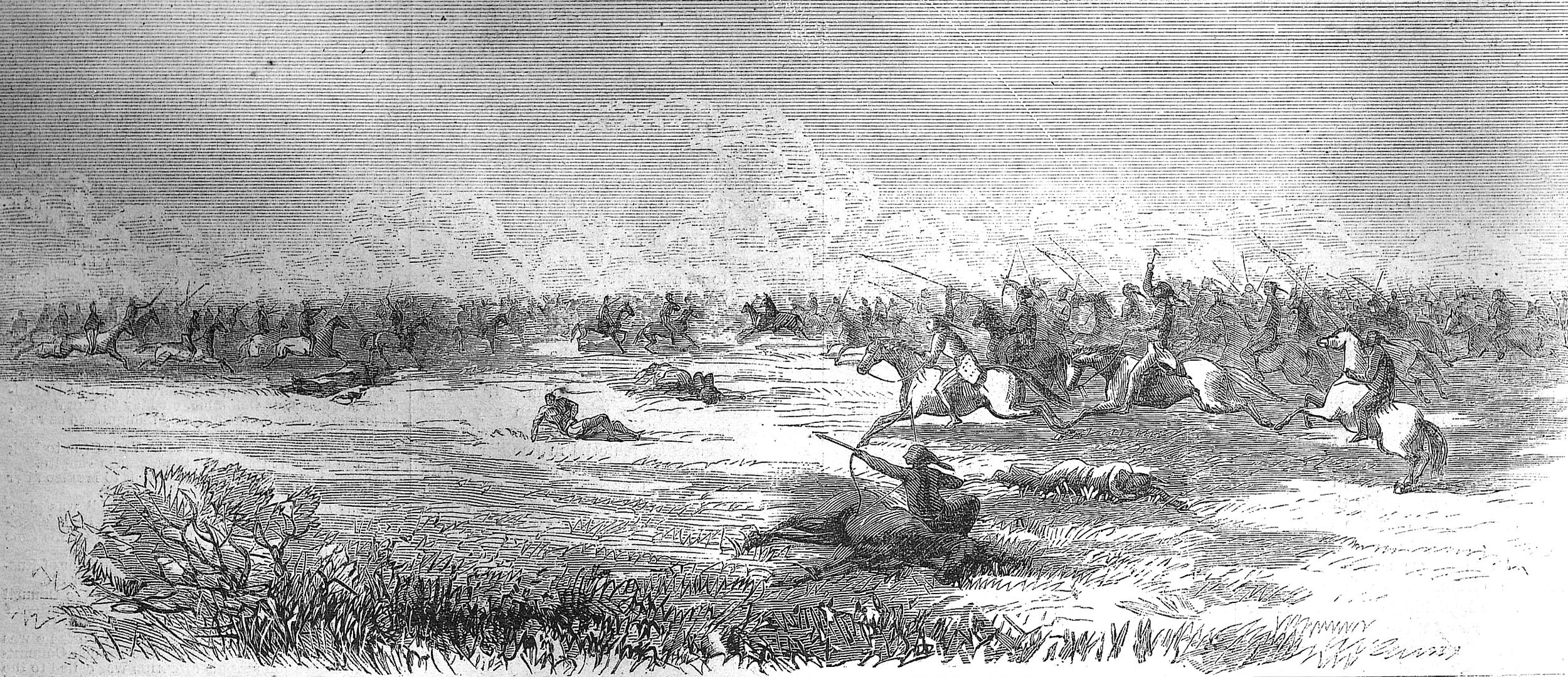

Suddenly the tables were turned, and the Indians—now heavily reinforced—went over to the offensive. They hit the skirmish line in front and flank, threatening to overwhelm the bluecoats before they could mount an adequate defense. Indian rifles crashed out, the hail of slugs supplemented by a steady shower of lethal arrows. By this time the reserve platoon was to the right of the hard-pressed skirmish line, riding abreast of their comrades. The reserve platoon was heavily engaged, but the real crisis was with the skirmishers.

All dissolved into chaos as the warriors smashed into the troopers’ skirmish line, “uttering their peculiar Hi-Hi-Hi and terminating it with a war-whoop.” War bonnets flashed white in the sun, the long, feathered tails floating in the wind like silken streamers as the warriors galloped in. Troopers fired at the milling targets, Spencer gun butts kicking into shoulders in heavy recoil. Once fired, a trooper would quickly work the carbine’s loading lever, the action expelling the empty cartridge into the prairie dirt and putting a fresh bullet in its place.

While troopers fired, loaded, and fired again with mechanical regularity arrows came pouring in, striking at random in a kind of grim lottery of death. Shafts would impale troopers, the steel-tipped points making a sickeningly hollow thumping sound as they entered blue-coated human flesh. Warriors came in for the kill, using lances, knives, or tomahawks to finish off their outnumbered foe. Some Indians tried to grapple with their enemies hand to hand in an effort to unhorse them. Dismounted troopers were easy prey, yet their Spencers still made them dangerous at close quarters.

High-spirited Indian ponies were smaller than cavalry horses, but could ride circles around the heavier cavalry animals. They, too, were dressed for war, their rippling flanks flecked with war paint and flowing manes festooned with feathers and scalp locks. Sergeant Wyllyams became separated from his men, and once isolated, his fate was quickly sealed. Shot, then tomahawked in the head so deeply the brain was exposed, the body was stripped and mutilated in short order.

It was amazing that warriors would take the time to strip a fallen foe, but they seemed to be practiced in the “art.” Trumpeter Charles Clarke took a bullet that tumbled him from his saddle. The still-warm corpse lay sprawled on the ground—but not for long. A brawny Indian galloped up, reached down, and flung Clarke across his horse like an old blanket. The warrior proceeded to deftly strip every piece of clothing from the body, sinking a tomahawk into the skull as a finishing coup de grâce.

Barnitz rightly feared that if the skirmish line retreated, the withdrawal might turn into a bloody rout. The captain also saw that the second, “reserve” platoon on the right was going too far right. After signaling Sergeant Haines to correct the deviation and to come to the aid of the skirmishers as soon as he could disengage from his own fight, Barnitz galloped over to the left to give his men fresh heart.

The ride to the right was a perilous one, as a warrior appeared out of the skeins of gun smoke to engage Barnitz in a kind of personal duel. Warriors were noted for their equine acrobatics, dazzling displays of horsemanship the troopers could never hope to duplicate, even if they wanted to. The captain’s opponent started firing his rifle, then suddenly “disappeared” by clinging to the animal’s heaving side. Thus using his mount as a living shield, the warrior proceeded to shoot his rifle from under the horse’s neck.

Barnitz, of course, was too preoccupied with the problems of command to give much thought to his personal safety. The Indian’s rifle pumped a steady stream of lead, the bullets zipping past the mustachioed captain, but Barnitz did not return fire. He merely pointed his pistol a few times in the warrior’s direction, hoping to save some rounds for a more favorable—and presumably, closer—opportunity. The Indian finally broke off the attack and went in search of more vulnerable prey.

The captain’s death-defying ride to the left was futile—the skirmishers were already in full retreat. Because of Sergeant Gordon’s horse mishap, Company I’s Sergeant Hamlin took control, with near-fatal results. Hamlin had already “distinguished” himself by leaving some comrades in the lurch in an earlier fight; now, he reverted to type. Hamlin drew rein and started to flee as fast as his horse could take him. Such panic is bound to be contagious, especially when displayed by a noncommissioned officer who is supposed to lead by example as well as by verbal order.

The Indians were among the fleeing troopers like wolves descending on a flock of sheep. In an effort to stem the tide Barnitz called for the men to rally on him, the shouts and exhortations soon gathering a handful of braver, less panicked troopers. Barnitz hoped to use these men as a nucleus upon which to build an active defense.

Fighting was still hard, and often hand to hand. Private Patrick Hardyman knew he was in trouble when a fierce-looking warrior rode up with a lance. Hardyman had lost his saber, and there wasn’t enough time to put another cartridge tube down the butt of his empty Spencer. Helpless, he braced for the blow, but was saved by the quick action of Corporal Prentiss Harris. Harris swung down with his saber, which the warrior quickly parried with his lance, but this blocking motion left his chest exposed. Sensing an opportunity, Harris maintained a steady pressure against the lance with his saber while simultaneously bringing his carbine up with his left hand.

Before the Indian could react Harris put the muzzle up against the Indian’s chest and pulled the trigger. The effect was predictable—and horrendous. The warrior’s chest exploded in a welter of smoke, blood, and torn flesh, the lead slug going right through his body to exit in a gory hole in his back. Reeling from the impact, the Indian slumped forward and was led off by two other warriors.

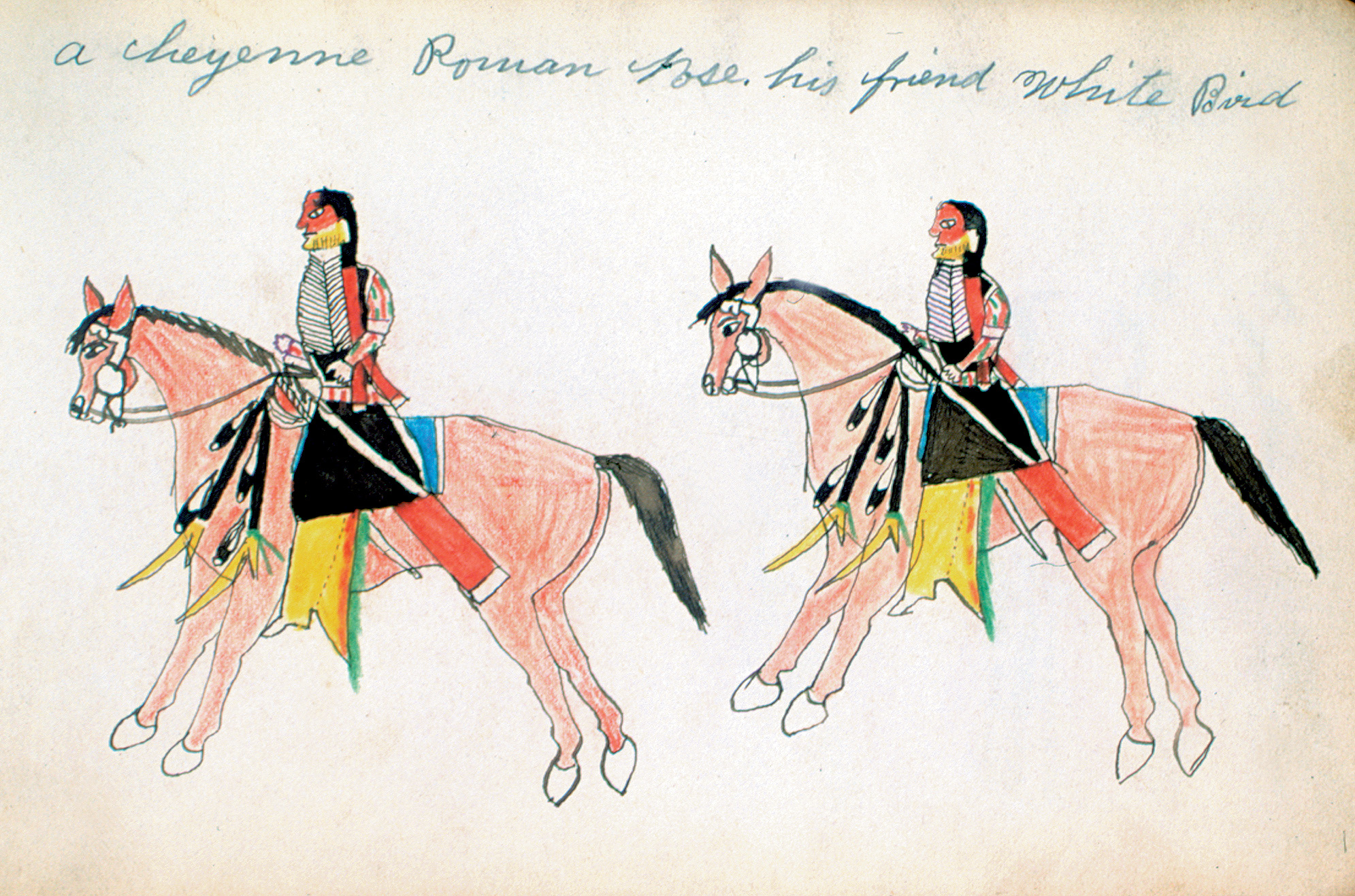

This incident became important when the warrior was identified by some as Roman Nose, a man so prominent in war the whites considered him a chief. Roman Nose was a Cheyenne traditional warrior in the same general mold of the Lakota Sioux Crazy Horse.

He did not want to give up the old ways—and was prepared to fight to the death to protect his people, land, and culture from encroaching whites.

It was widely believed that Harris had killed Roman Nose, but the allegations proved false. The great warrior apparently didn’t participate in the Fort Wallace fight, though this is disputed by some writers. All agree that Roman Nose survived, and was killed at the Battle of Beecher’s Island a little over a year later in 1868.

Everything depended on Barnitz managing to halt the retreat and set up an adequate defense. They were too far from the fort to seek shelter there—the stand had to be on the open prairie. Luckily, Barnitz and his handful of troopers provided the anchor that the other men needed. All rallied, and a steady barrage of Spencer slugs blunted the Indian advance.

Then the Indians suddenly departed, leaving Barnitz and his little band of soldiers in possession of the field. The captain stood his ground, but sent for an ambulance wagon from the fort to retrieve the wounded and pick up the dead. When the ambulance arrived to begin its grim work, Barnitz mounted the company and rode out in hopes of picking up the Indians’ trail. It’s not that he wanted to renew the engagement—far from it. He felt that he had to at least discover where the Indians were going. But about five miles from the post the trail ended, the Indians having scattered in all directions.

Captain Barnitz described the Fort Wallace clash as “a desperate little fight.” Six soldiers had been killed outright, while a seventh casualty, Corporal James K. Ludlow, was mortally wounded. Six others were also injured, but not fatally. Indian losses were hard to estimate because the natives usually carried off their dead. Sioux and Cheyenne losses were at least as great as the Army’s, and possibly greater. The battle had been a long one, lasting over three hours.

Sergeant Hamlin’s cowardice was the last straw for Barnitz, who knew his sorry record of unreliability. Hamlin was placed under arrest, and a couple of months later he deserted. But Hamlin’s disgrace could not wipe out a notable achievement for the Seventh Cavalry. The Seventh won some fresh laurels, and Barnitz was lionized by the eastern press. That brief moment of panic notwithstanding, most troopers fought bravely and well.

Barnitz later found out that the Indians who had attacked him were not yet ready to call it a day. Several hundred warriors, still seeking fresh laurels, had attacked the Seventh Cavalry supply train led by Lieutenants Robbins and Cooke about 30 miles from Fort Wallace. Contrary to Hollywood myth, the supply train did not circle the wagons to form a defensive line. The canvas-topped wagons were drawn up in two parallel lines, the cavalry troopers’ mounts sheltering between them. Dismounted skirmishers provided a screen of protection around the wagon line, a veritable “ring of fire” that was hard to breech. The supply train was rescued by the timely arrival of Captains Robert M. West and Edward Myers leading Companies D and E, Seventh Cavalry.

The fight at Fort Wallace afforded Dr. Bell a unique opportunity. The bulky equipment and, most importantly, the long exposure times of 1860s photography did not allow for photojournalism as we think of it today. Certainly, combat photos were out of the question. But Bell’s presence provided the next best thing—photos of the participants the same day as the battle. Thanks to Bell’s work, we can see cavalry soldiers who had just fought Indians. Modern viewers can see what the fort looked like, and can examine in marvelous detail soldiers’ uniforms, equipment, and weapons—the same weapons that had been firing at Sioux and Cheyenne that morning. A truly unique record.

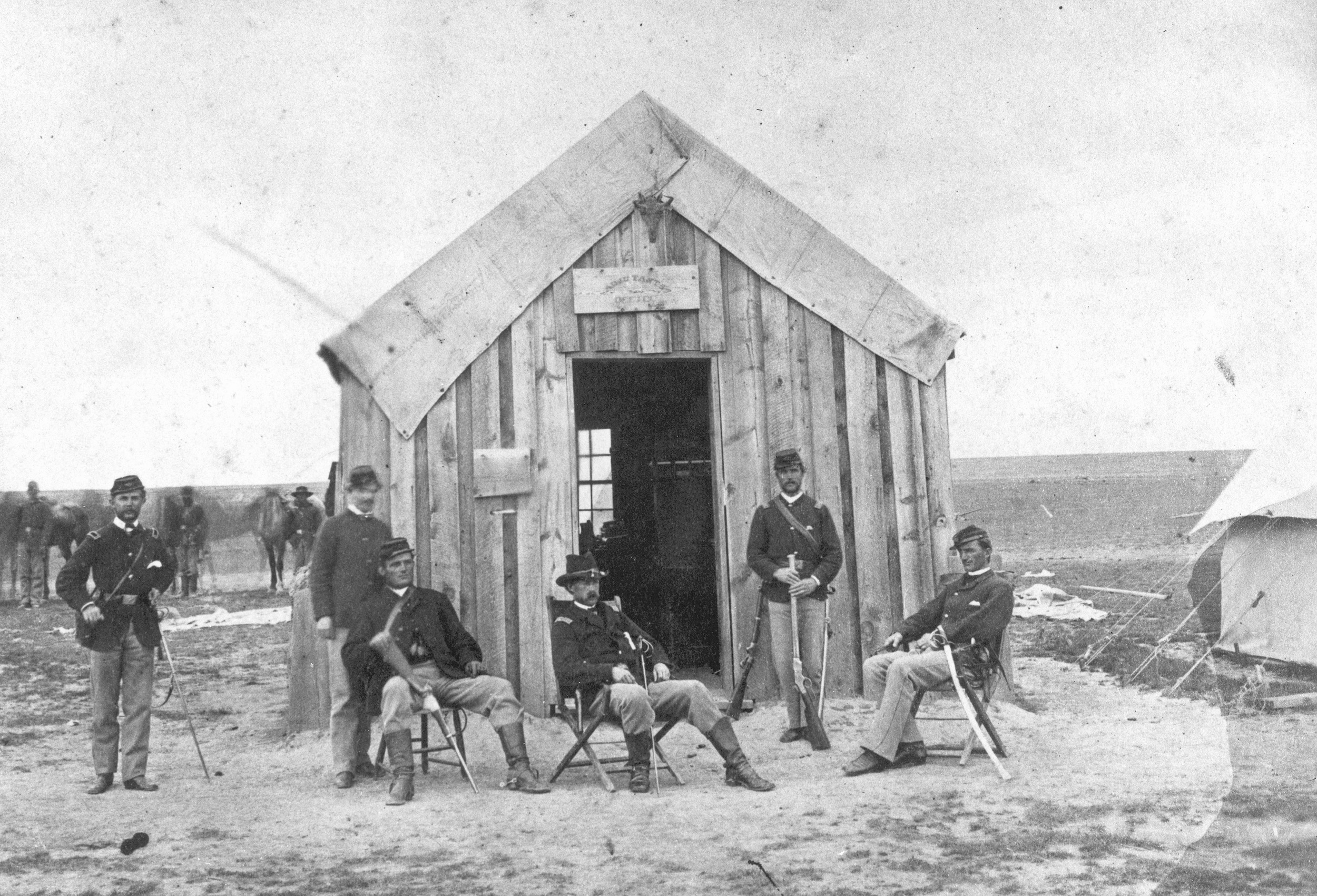

Bell lined the officers in front of the post adjutant’s office, a crude plank affair with a canvas roof and an antelope skull above the door. Barnitz is there, a seated figure clutching his saber and looking off into the prairie. One of the standing officers is Lieutenant Frederick Beecher, killed at the Battle of Beecher’s Island a year later.

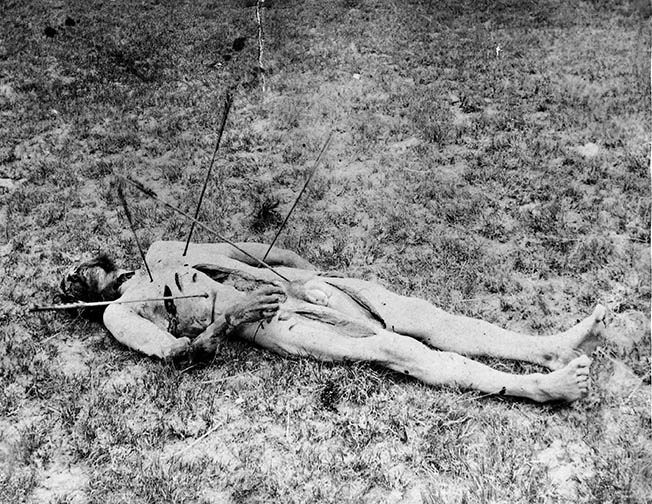

The photographer was sickened at the sight of the dead, and further distraught to see that his new friend Sergeant Wyllyams was among the fallen. As a doctor he was no stranger to death, but the corpse mutilations horrified him. The worst butchery had been done to Wyllyams; he was not merely scalped, but eviscerated. Here was another unique opportunity, albeit a grim one, to record Indian atrocities.

Wyllyams’ battered corpse was photographed just as it was found. The work was distasteful, but Bell felt he had a duty to record the unvarnished truth—not the romantic, sanitized version of warfare seen in Victorian literature. The chest cavity was ripped open, the arms and legs slashed to the bone. His throat was cut so deeply he was nearly decapitated, and several arrows punctured the naked corpse. Each arrow could be identified by the feather fletches and other markings. It was clear this was the joint work of Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors.

Why did the Indians perform such butchery? According to most sources they believed such mutilations would cripple an enemy in the spirit world.

Captain Barnitz was severely wounded at the Battle of the Washita in 1868. He survived, and lived until 1912, but the injuries to all intents and purposes ended his Army career. The Seventh Cavalry is best remembered for its stand at the Little Big Horn in 1876, but the first major Indian fight—the regiment’s true baptism of fire—took place nine years earlier at Fort Wallace. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments