By Arnold Blumberg

Napoleon Alexandre Duffie was born on May 1, 1833, in Paris, France. His father, Jean August Duffie, was a prosperous sugar refiner and mayor of the village of La Ferte-sous-Jouarre. The family, originally from Ireland, had fled to France during the Cromwellian conquest of the 1640s. In 1851, at age 17, young Duffie enlisted in the 6th Dragoons Regiment of the Imperial French Army.

Transferred to North Africa with his regiment, Duffie rose to the rank of sergeant. He and his comrades saw action in the Crimean War, participating in the battles of the Alma, Inkerman, Balaclava, Chernaya, Sebastopol, and others. Duffie was awarded the Order of the Medjidie from the Ottoman Empire and the Cross of the Legion of Honor from his own government. Back in France in February 1858, Duffie was made first sergeant and chief marshal of logistics. He transferred to the 3rd Hussars Regiment, reenlisting for another seven-year term. On June 14, 1859, Duffie was promoted to second lieutenant.

The Tall Tales of Napoleon Alexandre Duffie

Two months later he attempted to resign his commission but his request was rejected. In response, he fled to the United States. Court-martialed the next year, Duffie was found guilty of desertion, sentenced in absentia to five years in prison, and dishonorably discharged from the French Army. With prison hanging over his head, Duffie would never again see France. His reason for leaving France was his desire to be with 32-year-old American Mary Ann Pelton, daughter of Daniel Pelton of Staten Island, New York. The Pelton family was wealthy and politically well connected. Duffie had meet Mary when she was a nurse in Europe. The two were married August 19, 1860, at the Pelton homestead at West Brighton, New York.

Settling into his new life in America, Dufie fabricated a story about his family and military background designed to impress his new American associates. He transformed his middle-class father into an aristocrat, enhanced his former military education and career, and changed his birth date to 1835. He claimed that he had attended a preparatory military academy at Vincennes and entered the prestigious French Military College of St. Cyr in 1852, being one of only 220 accepted out of 11,000 entrants. He further alleged that he had graduated with honors from St. Cyr and then been commissioned a lieutenant in the French Army and posted to North Africa.

Duffie similarly exaggerated his Crimean War exploits, claiming that he had been wounded multiple times during the war. He also claimed to have participated in the fighting in Italy in 1859 as a first lieutenant in the 5th Hussars Regiment, again receiving battlefield injuries, the most serious at the Battle of Solferino on June 24. Continuing to weave his deceitful tale, Duffie said he had come to the United States to recover from his latest war wound. He alleged a total of eight injuries received in combat in the French service, but none could ever be verified. He never uttered a word about desertion from the French Army or the asthma condition that affected him his entire adult life. Most outlandishly, Duffie claimed to have received the English Crimean War Medal from Queen Victoria herself.

Receiving His Command in the Civil War

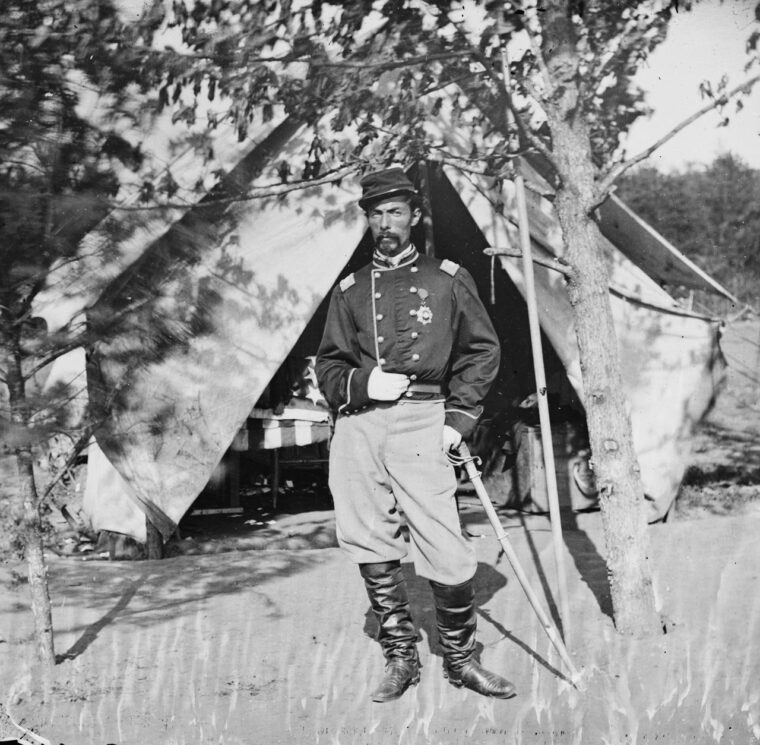

Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War, Duffie’s military masquerade and political connections through the Peltons secured him a major’s commission in the 2nd New York Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. With a flair for the theatrical that predated the flamboyant George Armstrong Custer, Duffie wore a uniform of his own design based on the French light cavalrymen attire, including leather knee-high boots and a high-crowned fatigue cap. Respected by his officers and men, the little Frenchman was called by his nom de guerre, “Nattie.”

Duffie was promoted to colonel and given charge of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry Regiment in July 1862. When the regiment heard that a foreigner was coming to command them, the unit’s officers all tendered their resignations. The enlisted personnel were also alarmed at the prospect of a Frenchmen taking the regiment’s helm. Rumors had spread that Duffie was mercurial, irascible and cared not a bit about the comfort or safety of his men. Upon arrival at the 1st Rhode Island’s camp, the new colonel immediately took charge, threatening to cashier any officer who did not rescind his resignation request. He assured his officers in his fractured English that although “you not like me now, you like me by and by.” In a few weeks’ time, his program of training and firm but fair discipline, as well as his wry sense of humor larded liberally with curse words, won over the Rhode Islanders.

“Steady Men; Don’t You Stir; We Fix ‘em; We Give ‘em Hell!”

Duffie and his command tasted combat at the Battles of Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas, and Chantilly as part of Brig. Gen. George Bayard’s cavalry brigade in Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia. At the engagement at Groveton on August 28, the colonel exhibited his calm under enemy fire by halting in a road within easy range of Confederate artillery. There he deliberately rolled a cigarette. Even after an enemy round showered him with dirt, he merely brushed off his clothes and calmly lit his smoke.

During the Maryland campaign, Duffie’s regiment was assigned picket duty along the Potomac River, thus missing the Battle of Antietam. After the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, Duffie spent the next few months drilling his officers and men in the finer points of mounted warfare. On March 1, 1863, the Frenchman was given control of one of the brigades in Brig. Gen. William W. Averell’s cavalry division. Duffie was regarded as one of the best drillmasters in the Army of the Potomac, and he had planned to carry out a program of instruction so that his new brigade would be able to efficiently work together as a cohesive combat unit. However, he did not get the chance to put his scheme into effect before his new command was thrown into combat.

Ordered to move on Culpeper, Virginia, and attack the Rebel cavalry there, Averell crossed the Rappahannock River with 2,200 troopers at Kelly’s Ford on March 17, 1863. While traversing the river, Duffie was thrown into the water after his horse was hit by an enemy musket ball, badly bruising his leg. During the subsequent fight with 800 Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Duffie conducted a mounted charge that drove back the surprised foe. Attempting to recapture the initiative on that part of the field, the Confederate cavalry counterattacked.

Seeing the onrushing enemy approach, Duffie shouted to his command, “Steady men; don’t you stir; we fix ‘em; we give ‘em hell!” Moments later he led the U.S. 5th Cavalry Regiment in a countercharge that repulsed the surging Confederate horsemen. Duffie’s leadership did much to contribute to the first large-scale Union cavalry victory of the war. Kelly’s Ford showcased Duffie as an aggressive and battle-wise commander.

Brandy Station: Duffie’s Battle to Lose

During the Chancellorsville campaign, Averell’s division accomplished little, merely conducting a fruitless pursuit of some Confederate cavalry to the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers while the rest of the Army of the Potomac fought for its life. As a result, Averell was transferred out of the Army of the Potomac and replaced by Duffie. This assignment marked the zenith of Duffie’s Civil War career. Viewed as extremely ambitious, he had always sought recognition and advancement. One Union officer who had served with Duffie in the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry described him as “more or less a thorn in the side of the higher officers. He was not compatible with them, did not think as they did, had little in common, and was perhaps inclined to be boastful.”

Leading his regiments at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, the largest cavalry battle of the war, Duffie advanced toward Stevensburg, Virginia, placing him in the rear of Confederate Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart’s mounted force, which was pinned down fighting the balance of the Federal cavalry corps. Thus positioned, Duffie could have won the battle for the Union cavalry by immediately turning north and striking Stuart from behind. However, his lethargic advance to Stevensburg and the sluggish fight he conducted to clear the town kept him from moving swiftly. Concerned for his career, Duffie missed his biggest opportunity for glory and success.

Duffie’s failure at Brandy Station gave his enemies in the military establishment an opportunity to undermine his standing. Foremost of these was Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, commander of the newly formed Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Declaring that “I have no faith in foreigners saving our government or country,” Pleasonton added, “In every instance foreigners have injured our cause.” He stripped Duffie of division command, reducing him once more to leader of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. Worse luck would befall the Frenchman soon.

Duffie’s “Gallant Debris”

After his demotion, Duffie persisted in requesting an independent command. Pleasonton obliged by instructing Duffie and his regiment to scout Loudoun County, Virginia, in the vicinity of Middleburg, mandating that they remain there for the night before continuing their reconnaissance the next day. The task placed the 1st Rhode Island behind enemy lines, six miles from friendly forces stationed at Aldie. Pleasonton never stated why he ordered such a dangerous assignment, but it may have been concocted as a way to further discredit the unwanted Frenchman.

After reaching Middleburg and driving off Stuart and his staff, Duffie was surrounded by masses of Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson. Pleas for help sent to Duffie’s brigade leader, Brig. Gen. Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, were ignored, and the next morning Duffie’s regiment was assaulted from all sides. In their commander’s evocative words, the regiment was reduced to “gallant debris,” with 225 men killed, wounded, missing, or captured out of the 280 who had started the mission.

The debacle at Middleburg was partially Duffie’s fault. Having been given a suicidal mission by his superiors, he failed to retain control of the situation through lack of leadership at critical moments. He should have ordered a retreat to Aldie instead of remaining in the area overnight. During the escape attempt the next day, Duffie detached himself from his rear guard and completely failed to exercise command or control over his men during their flight. His defense to the affair, stated many years later, was that “I certainly could have saved my regiment in the night, but my duty as a soldier and as colonel obliged me to be faithful to my orders.” Duffie further mused that his orders had been designed to destroy his military reputation.

An Ironic Promotion

At the lowest point in his military career, Duffie ironically was promoted brigadier general of volunteers later that month. His elevation had been initiated by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, a former commander of the Army of the Potomac, who had been impressed with Duffie’s performance at Kelly’s Ford. Upon receiving the news, Duffie reportedly exclaimed: “My goodness, when I do well, they take no notice of me. When I go make one bad business, make one fool of myself they promote me, make me general.”

In September he was transferred to the Military Department of West Virginia. There he raised and trained a cavalry force of 3,000 men. Within two months he had created a fine contingent of mounted soldiers, temporarily assuming command of a combined infantry and cavalry division in the department. At the start of 1864, Duffie found himself a brigade leader once again under Averell. Neither man had ever been cordial toward the other, and Averell was particularly bitter over his replacement by the former as cavalry division commander in the Army of the Potomac the previous year. Coming under the abrasive and controlling Averell would only dim Duffie’s chances for independent assignments and further advancement.

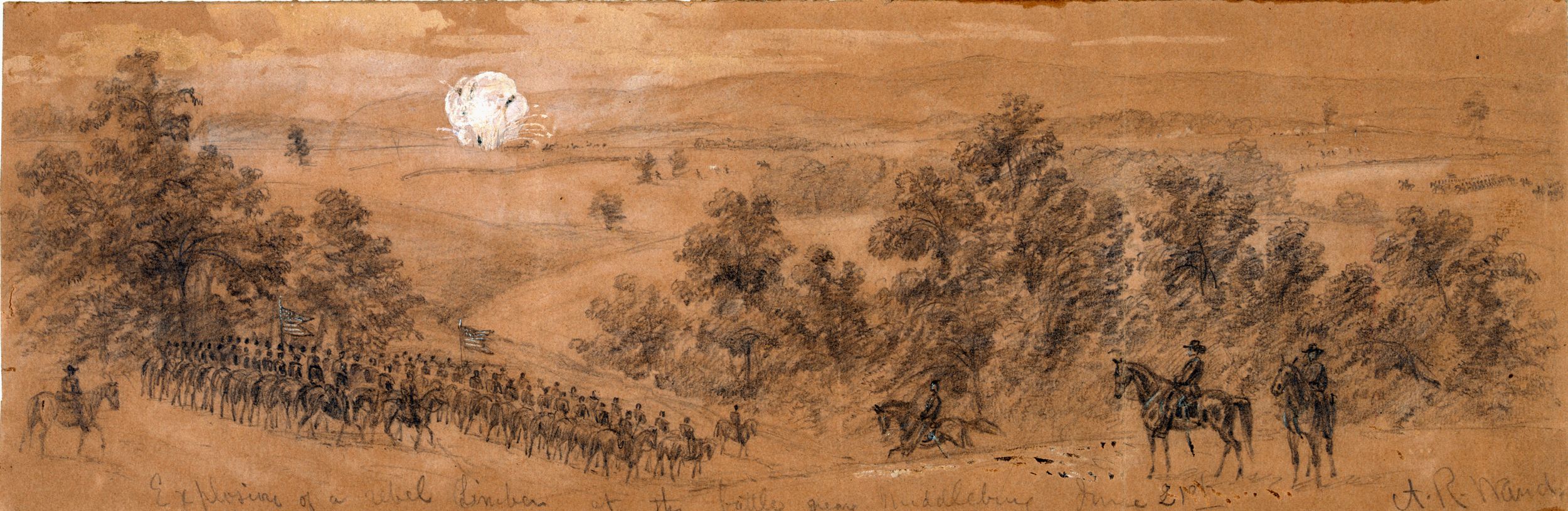

In June 1864 Duffie was unexpectedly freed from Averell when he was given command of a two-brigade cavalry division under Maj. Gen. David Hunter in the Shenandoah Valley. During the Battle of Lynchburg on June 17, Duffie’s advancing troopers made little headway against the determined Confederates opposing them, but after the fight he did a good job of clearing the way for Hunter’s arduous 12-day retreat over the Blue Ridge Mountains to the Kanawah Valley. The severe trek over hostile terrain in blistering heat ruined Duffie’s command and wrecked Hunter’s army so badly that it was unfit to take the field again for more than a month.

Sacked by Sheridan

Duffie next saw action on July 23 south of Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley, fighting the gray cavalry to a standstill. The next day, at the Second Battle of Kernstown, Duffie fought competently and with courage, keeping his hard-pressed men under control and unleashing a well-executed mounted charge on the advancing enemy that allowed many blue-coated infantrymen to escape.

For the next three days Duffie’s 1st Cavalry Division skirmished with the enemy while covering the Federal army’s withdrawal toward Martinsburg, West Virginia. Between late July and August, Duffie was engaged in constant fighting as Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early maneuvered against the Federals under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan in the Valley. In early September Sheridan ordered Duffie’s division to Cumberland, Maryland, to be remounted and refitted. On October 19, Sheridan unexpectedly relieved Duffie of command. Sheridan gave no reason why he sacked Duffie, but his ill-concealed dislike for the officer corps of the eastern armies likely had something to do with it.

“He was Captured by His Own Stupidity”

On October 21, Duffie traveled to Sheridan’s headquarters near Winchester to plead for a new field assignment. Sheridan consented, giving Duffie the task of raising and training a new cavalry unit. After leaving the meeting Duffie, traveling without an escort, was captured three days later by Colonel John S. Mosby’s Partisan Rangers five miles north of Winchester. Upon learning of the Frenchman’s seizure, Sheridan wired Army Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck: “I respectfully request his [Duffie’s] dismissal from the service. I think him a trifling man and a poor soldier. He was captured by his own stupidity.”

Sent to a prisoner of war camp at Danville, Virginia, Duffie engineered an escape attempt that failed. He was paroled on February 22, 1865, and posted to the Department of Arkansas, then to the Department of Kansas to reorganize and train the cavalry contingents there. On June 5 he was honorably mustered out of the United States Army.

As a result of his status as a war veteran and his in-laws’ continuing influence, Duffie was named United States consul in Cadiz, Spain, in 1869. He died of tuberculosis in that city in 1880 and was buried on Staten Island. As a sign of respect for their former commander, veterans of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry spent eight years raising money for a monument in his honor. It was unveiled on July 10, 1889, by the 1st Rhode Island Veterans Association at Duffie’s gravesite.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments