By Chris Blenheim

At midnight, the jumpers of 2nd Battalion, 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, as well as the 596th Parachute Combat Engineer Company, still dripping from the paint-spray line, shuffled across Ombrone Airfield to the waiting C-47s of Serial 6 and climbed aboard. Some were so weighed down that air corpsmen had to assist them aboard.

[text_ad]

The airborne combat engineers were not only weighed down with a heavy load, but with dangerous explosives. “We jumped with boxes of tetro caps above our reserve chutes,” Hal Roberts, combat engineer of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment, said. “These were wooden boxes, felt-lined, with 24 caps each about the width of a pencil. If those exploded, there’d be nothing left of you. So you protected those things. They figured the only way we could get them down without exploding was with us absorbing the impact shock of landing.”

The details of Operation Dragoon were mind numbing. Three hundred thousand men. Several thousand planes. A thousand ships. An advance force of 5,600 paratroopers in 396 C-47s, so large it demanded its own operation title: Albatross.

Preparing for the Jump: “God Bless You”

Before equipment was packed up, it was neatly laid out on shelter halves for an officer’s inspection, then packed. Each man had two bandoliers of .30-caliber rifle ammunition, half a belt for the squad machine gun, Mae West, a full musette bag, escape pouch, canteen, entrenching tool, an M-1 carbine with a folding stock or a standard M-1 rifle broken down into three parts in a Griswold case, bayonet, three knives, shelter half, raincoat, main parachute, reserve parachute, and enough K rations, C rations, and concentrated chocolate D bars to last three days.

Most of the men painted their faces with black and green camouflage from Lily Daché cosmetic tubes, and some shaved their heads to resemble Mohawks. The Nazi propagandists used this as proof to the French people that the Americans were murderers and lunatics. Some GIs, later lost in the French countryside, had asked Frenchmen for directions, only to scare them silly.

The engineers did not jump as a company. Third Platoon jumped with 3rd Battalion, while Company Headquarters and 2nd Platoon came with Regimental Headquarters. First Platoon jumped with the 509th Combat Team. As part of Company Headquarters, Hal Roberts’s plane lifted off around 1:30 am, flew north along the coast of Italy, then veered northwest at Elba.

“We could see the marker ships below,” he remembered. These were positioned to guide the armada with marker lights. “After the last one of them, we turned inland, so I thought, ‘I’m not going to need this Mae West anymore,’ and I chucked it.”

Anticipating the jump, the last man, the pusher, inched forward, causing the whole stick of jumpers to close in tightly before the door. All the men had the forward lean of marathon runners on their mark. Hal put his shoulder into the man in front as he watched the red light. Before the jump, Lieutenant Larson said three lasting words that echoed in his mind until he jumped: “God bless you….”

Greeted by Machine-Gun Fire

At 4:32 am the red light went out, and a green light pushed reality into gear.

“Go! Go!”

The jumpers literally pushed the men in front of them so that the plane flushed the men out in a long string within about four seconds. Any sizable gap between men could mean a jumper lost or dead. They went out at 1,500 feet, twice that of a normal combat jump.

Just before the jump, the planes had climbed above the thickening clouds where the moon illuminated the blanket of white into what appeared like a shimmering sea. “As I got out into the sky,” Roberts recalled, “I thought, ‘Oh God, I thought we went inland! Am I going into the drink without my Mae West?’”

Weighed down by his rucksack, a trooper tangled in a mass of suspension lines might well drown. But relief swelled within him as he slipped silently through a sheet of moonlit clouds and into the black night below.

“Before I hit the ground, I could hear the rapid burp of gunfire,” Hal related. This was the German MG-42, a machine gun that could fire up to 1,200 rounds per minute. Instead of emitting the familiar bup-bup-bup-bup of the American M2 .50-caliber machine gun, it emitted the sound of ripping canvas, a buzzsaw, or a protracted belch.

“I crash-landed in the bushes,” said Hal. “I didn’t know what I was in or where I was, but there was lots of burp gun fire. And they fire so fast! I thought, ‘This is not good.’”

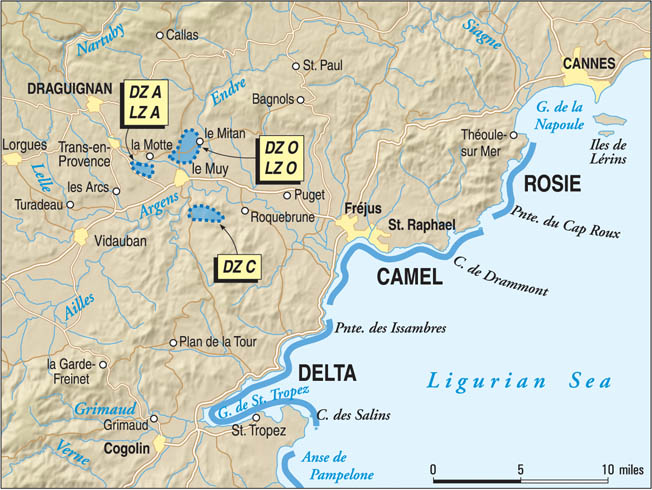

Hal had landed in a vineyard in the town of Le Muy, miles away from his planned drop zone and the rest of Headquarters Company. Row after row of low-growing grapevines striped the rock-hard soil and ran lengthwise between a road and a dry riverbed. All around him were pockets of gunfire and shouting men, all veiled in darkness.

“I wasn’t able to double up, due to a bush that was jammed into the parachute backpack, so I couldn’t get my chute off,” he said. So Hal called out for help to any jumper who might be in the next row of low-level shrubs. The MG-42 immediately ripped through his area.

The only thought to rush through his head was, “They’re shooting at me! I can’t believe they’re shooting at me!”

Fear paralyzed him. Adrenaline shot through his veins.

Clyde Hoffman, who had been right behind Hal in the jumping stick, crashed in the distance and in Hal’s row of grapevines. Hoffman crawled to his position.

“You alright? You hit?”

“No, I’m okay. But this is one helluva way to greet visitors.”

“Hey, are you flipping your wig?”

“I can’t get outta my chute.”

Hoffman took out his trench knife and cut away at the harness material.

“Wait a minute, you’re cutting me!” Hal grimaced, pushing at the edge of a whisper. Rounds were tearing up the bushes all around them since Hal’s white chute, draped clearly over the shrub, marked his position. Soon he was free, and they moved under the only cover the orchard would afford at a low crawl, lower than a snake’s belly, low so that your helmet is plowing a trough for you to crawl through, low so that your waistband scoops dirt into your underwear and you don’t care, just as long as the German machine gun does not find you.

Every time Hal pulled his leg up to move, it bumped his entrenching tool and the sound invited more fire. The Germans were listening very intently.

He ditched it and his rucksack; they were too big. Any sound made the enemy machine gun come alive, and each man’s insides recoiled with the thought that any one of those rounds had his name on it.

They remained still, and all was silent between bursts.

The Art of Camouflage

Hal and Clyde weighed their situation. At one end of the row was a two-story building, beside it a tree that held a paratrooper above the ground. His body gently rotated in the harness like a hanged man at the gallows. The eastern sky showed some color.

“Listen,” Hoffman whispered. “It’s going to be daylight soon. With that machine gun, we’re not getting out of here. And they’re gonna be patrolling through here at daylight.”

“What’re we gonna do?”

“Listen, the gliders should be coming in soon. Once they do, that’ll take some of the heat off of us. Then we can move.”

After weighing a certain death against an uncertain future, they agreed to dig in. For over an hour, the two paratroopers carefully cut free strands of shrubbery and camouflaged each other. Each man slipped into the small hole he had made in the bush and pulled more branches in, above, and behind.

“How do I look?” Hal whispered.

From his side in the shrubbery, Clyde nodded. Sunrise soon discovered them, shining light through the leaves and quickening their feelings of vulnerability. They watched as a group of German soldiers swung a dead American paratrooper, hanging in his harness, against the side of the tree he landed in. The Germans smoked cigarettes and laughed.

The two Americans heard slow footsteps from behind. Hal thumbed the safety of his .45-caliber pistol.

A pair of boots and the muzzle of a rifle came into view. The German’s leather soles crushed pebbles into the soil. Hal shifted only his eyes into the next row where Hoffman lay, hoping Clyde’s camouflage resembled that of his own.

The faceless Nazi passed them by. Hal thought the soldier would hear his thumping heart. After what seemed an eternity, they slowly crawled free of the vines so that anyone watching the rows could not detect movement. At the opposite end of the orchard was another two-story building heavily fortified by a rock wall. Hal motioned to Hoffman to go toward the riverbed. They began their long journey on their bellies over and through the bushes, not as men, but as clumps of vegetation moving slower than the eye suspected.

Taking Out an MG-42 Team

They found other 517th jumpers—dead. They had tried to run out of the orchard in a low crouch, which put them high enough for the MG-42 alongside the road to be effective. The gun had worked the whole orchard that night.

From the last row of grapevines they spotted the riverbed. “The rocks were white as snow,” Hal recalled. “We’d have been dead before two steps.”

They turned back and crawled past the fortified building. A sentry on top of the building looked out over the orchard and the surrounding countryside, then turned and disappeared for a few moments, only to return. They found a pattern to the guard’s boredom, and they moved during his absence.

With dead ends on three sides, that left only one option: the road, which was protected by the machine-gun emplacement. They slowly moved their way into a position alongside the road where they could view it. It took six hours to crawl this route of a few hundred yards at a snail’s pace with hearts beating time.

Two German soldiers manned the machine gun, a triggerman and a belt man who also had to frequently change barrels on a weapon with such a high rate of fire. They focused their gun over the open field and into the hills where activity was increasing. Hal raised his M-1 Garand and fired two rounds, one right after the other. They were so close that he did not even use his sights. The triggerman fell, then his assistant.

Hal mused, “There was only one way out, and that’s what I had to do to survive.”

Rendezvous With the British

Running parallel to the road was a ditch full of water. Had they known about it from the beginning, it would have saved them hours of low crawling. They slid into the ditch just as mortars started dropping where they had been. Hal found himself up to his neck in water. Clyde was about a head shorter. They slogged along this waterway, passing underground and into the cattails, covering their trail as they went. After being in the cold water so long, the sun-warmed cattails felt wonderful.

“We came across this little French kid, 10 years old or so,” Hal recalled. “He came up to me and grabbed my arm and kissed my shoulder patch. He said, ‘L’anglais est là,’ pointing the way, and I said, ‘Merci.’” We made our way over there and met up with 40 Brits commanded by an English major. They had been running into trouble, so I told them, ‘You’re going to have clear going because there was a machine gun there that’s not there anymore.’ They said, ‘Yank, come on aboard!’ Hoffman and I didn’t have our packs; we had left them in the orchard and donated them to the enemy. So the English gave us food and ammunition.”

The unit, likely part of the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade, was preparing a raid on the fortified command post, the same one with its inattentive guard that Hal and Hoffman had passed that morning. The plan was to approach the command post on the opposite side where a huge cornfield lay.

One of the first things they told their American friends was, “You don’t need that helmet.”

They tore off triangles of camouflaged parachute silk and gave them to the Americans.

“Why?”

“It makes less noise, and you don’t need anything that doesn’t stop bullets. That helmet doesn’t stop bullets. Maybe a little shrapnel and mud and dirt falling on your head, that’s all.”

Seeing how the Brits wore bandanas, the Americans followed suit. They sat in a cornfield in the warmth of the sun, preparing their equipment for the task at hand, packing plastic balls of composition C2 explosive with tetra caps.

“What’re we doing?” Hal asked.

“Yank, we’re making Gammon grenades!”

“Bash ’em! Bash ’em!”

At about 2:30 pm, the major gave his men the command, and the two Yanks went along for the ride. The lead element sprinted across the field, a number of them yelling, “Bash ‘em! Bash ‘em!” The first set of men who made it to the wall tossed Gammon grenades over and stood there, the next set hunched down behind them, the third set crouched on hands and knees—all together forming a human staircase. The remaining Brits ran up their backs, shouting and throwing grenades. Plumes of black smoke erupted from behind the wall, and the Brits jumped headlong into them with Tommy guns firing.

By the time Hal and Clyde got over the wall, the Brits had opened the gate from inside. They ran into the command post to find the Brits stitching the ceiling both ways with hundreds of rounds. “They were just running those Tommy guns, constantly firing. Those guns were hot,” Hal remembered.

They had taken the command post in less than 10 minutes. The Germans suffered 30 dead and 80 taken prisoner. Then Hal discovered why the British had worked so fast: tea time. “These Limeys,” Hal recalled with a laugh, “they took out their Bunsen burners and had their spot o’ tea! Three in the afternoon, time to take a vacation from the war! I thought if I was these Germans, I’d time everything to take place at three in the afternoon!”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments