by Mike Haskew

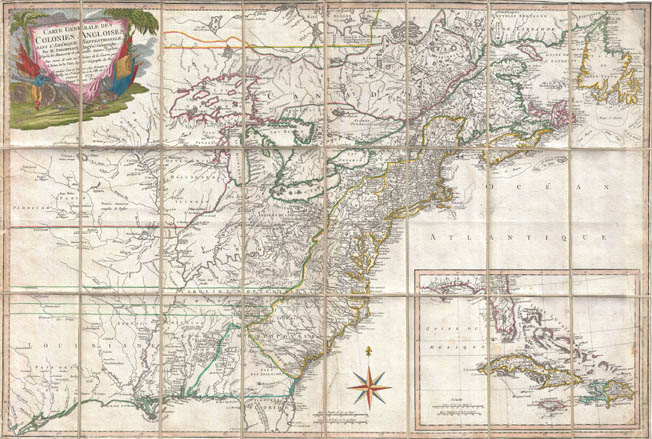

Although a large number of colonial slaves fled their condition of involuntary servitude seeking freedom through service to the British Army, an estimated 5,000 African Americans served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Among these patriots were both slaves and free blacks. Other African American Revolutionary War Heroes contributed to the fight for freedom in uniquely remarkable ways.

[text_ad]

Crispus Attucks: Martyr or Rabble-rouser?

Five years before the Revolution began on Lexington Green, Crispus Attucks became one of the first martyrs of American freedom on March 5, 1770. He was among the leaders of a group of patriots, citizens of Boston who resented the presence of British soldiers among them, who had gathered to jeer and taunt a number of British soldiers in the street. Boston had been a hotbed of resistance to British rule and the cradle of the independence movement, and Attucks, a dockworker, has been described by historians both as a free man and as a slave. Regardless of his status, Attucks carried a cordwood club and urged his followers to disarm several British soldiers that had approached them with fixed bayonets. Attucks was heard to say, “Let us drive out these ribalds. They have no business here.”

Suddenly, shots rang out. Attucks was hit twice in the chest and died immediately. Four other patriots were killed, and the incident became known as the Boston Massacre. Attucks is considered by many to be the first American casualty of the Revolutionary War.

Prince Esterbrooks: First in the Fight

Ten African Americans were known to have fought with the colonists at the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. Among them was Prince Esterbrooks, who was described three days after the battle by a local newspaper as a “Negro man” who was “wounded (Lexington).” Witnesses described Esterbrooks as “the first to get into the fight” during the opening skirmish of the American Revolution. Another African American who served his fledgling country was John Redman, who applied for a pension more than 40 years after the Revolution ended, stating that he was a veteran of the First Virginia Regiment of Light Dragoons. Redman’s pension was granted.

James Armistead: Serving With Lafayette

James Armistead was one of at least eight slaves granted their freedom by state legislatures for services rendered during the Revolution. Armistead served with the Marquis de Lafayette, a young French nobleman who became a trusted confidante and lieutenant of General George Washington. At the risk of his life, Armistead slipped out of Yorktown, Virginia, before the fateful siege that doomed the British cause in North America and returned periodically to the British lodgments around the town to gather valuable information. In October 1784, Lafayette wrote a letter confirming that Armistead had performed “essential service” while gathering “intelligence from the Enemy’s camp.” Lafayette asserted that Armistead was “Entitled to Every Reward His Situation Can Admit of.” Although it was slow to come, Armistead, who eventually changed his surname to Lafayette, was emancipated on January 9, 1787.

Peter Williams: Advocate for Independence

First in New York and later in New Jersey, clergyman Peter Williams was a voice advocating American independence from Great Britain. When New York City was occupied by British troops, Williams moved to the neighboring state and continued to rouse patriotic fervor among the colonists. His activities cultivated the ire of the British, who sought to arrest him. Williams, however, appealed to his parishioners for assistance and was able to elude capture by the British.

The contributions of African American patriots to the cause of freedom resonate across more than two centuries and provide a heroic chapter in the story of the Revolution.

Originally Published July 23, 2014

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments