By Blaine Taylor

The boots and riding crop of the Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Corps, General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, are there, as well as the cap and jacket of his successor in a second world war, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. In addition to American military history items, one can find a bust of King Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia presented by his successor, German Kaiser

Wilhelm II; Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg’s personal telephone from General Headquarters at Spa, Belgium; and an Austro-Hungarian field marshal’s tunic believed to have been worn by the Hapsburg dynasty’s next-to-last emperor, Kaiser Franz Josef I, who ruled from 1848-1916.

Then there are American Vietnam War commander General William C. Westmoreland’s jungle fatigues; a Prussian Garde du Corps cuirassier regimental sergeant’s breastplate, helmet, and accoutrements; the presentation sword of former Army Chief of Staff General Peyton C. March presented to him by the citizens of his native city, Easton, Pa., on May 31, 1918.

Also on view is the French 75mm field gun and carriage from WWI that fired the first artillery round of the BEF against the Germans in France by the 6th U.S. Field Artillery, as well as a Chinese Type 56 rifle caliber 7.62mm used in the Korean War and presented to the West Point Museum by a famous member of the Class of 1915, the late five-star General Omar Nelson Bradley.

A World War II jeep is in the collection, as is a famed Norden Bombsight that did much to level the cities of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan during that conflict.

One can also see the pistols of both George Washington and Napoleon (as well as a personal sword of the latter) and portraits of each; a diorama of the epic Revolutionary War Battle of Saratoga on October 7, 1777; and the personal saddle of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, a Union commander killed in action at the Battle of Spotsylvania in May, 1864.

Union Civil War General Philip H. Sheridan’s sword is in the collection. So is the personal gray bathrobe of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, who was superintendent at West Point from 1919 to 1922.

These are all in the museum at the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, the oldest and largest collection of military items in the nation.

The USMA is thought to have the toughest undergraduate curriculum in the world, and one of the many and varied missions of its museum is to assist these and other cadets in their studies throughout their quartet of years.

One boast of Lt. Col. Eugene J. Palka of the USMA Department of History is that “much of the history we teach was made by those we taught.”

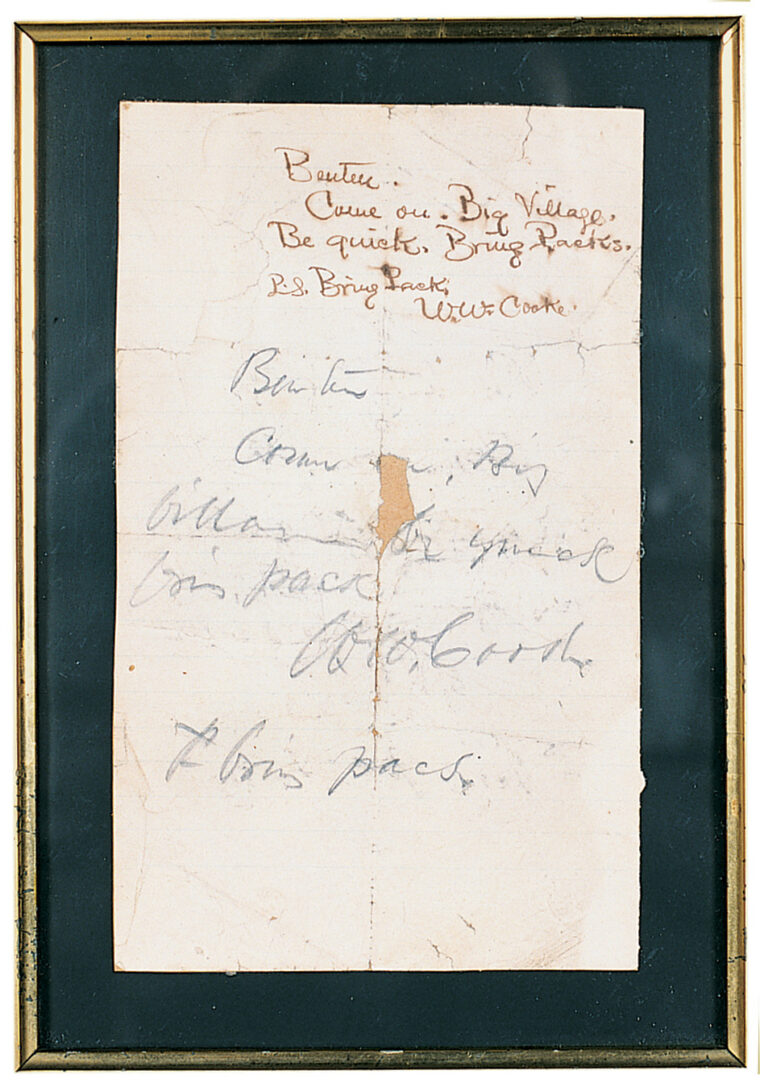

One of the most famous holdings in the collection is the last dispatch sent by Colonel George Armstrong Custer on June 25, 1876. According to David M. Reel, Curator of Fine Art and Decorative Art for the West Point Museum (WPM): “Just before riding into the valley of the Little Big Horn where he encountered the greatest concentration of hostile Indians in the history of North America, Custer sent a message to his subordinate, Capt. Frederick Benteen. The dispatch, written by Custer’s adjutant, Lt. William W. Cooke, reads, ‘Benteen. Come on. Big village. Be quick. Bring packs. W.W. Cooke. P.S. Bring pacs [sic].’

“The man who delivered the message to Captain Benteen, an Italian trumpeter named Giovanni Martini, was the last man to leave Custer’s presence. Custer’s command had already been cut off by the Indians, so Benteen was unable to follow the orders. In a letter to his wife dated July 4, 1876, Captain Benteen quoted Custer’s dispatch and added, ‘I have the original, but it is badly torn and it should be preserved.’ He subsequently gave the dispatch to a friend in Philadelphia, who later sold it to a collector in New Jersey. Col. E.W. Bates acquired the manuscript at auction and donated it to the United States Military Academy.”

Mr. Reel and his colleague, Curator of History Michael J. McAfee, serve with Museum Director Michael E. Moss at the WPM location at 2110 New South Post Road, USMA, West Point, NY, in the new Pershing Center on post. In turn, they report to the current USMA Superintendent, Lt. Gen. William J. Lennox, Jr., because the museum is officially a department of the overall USMA administrative organizational setup.

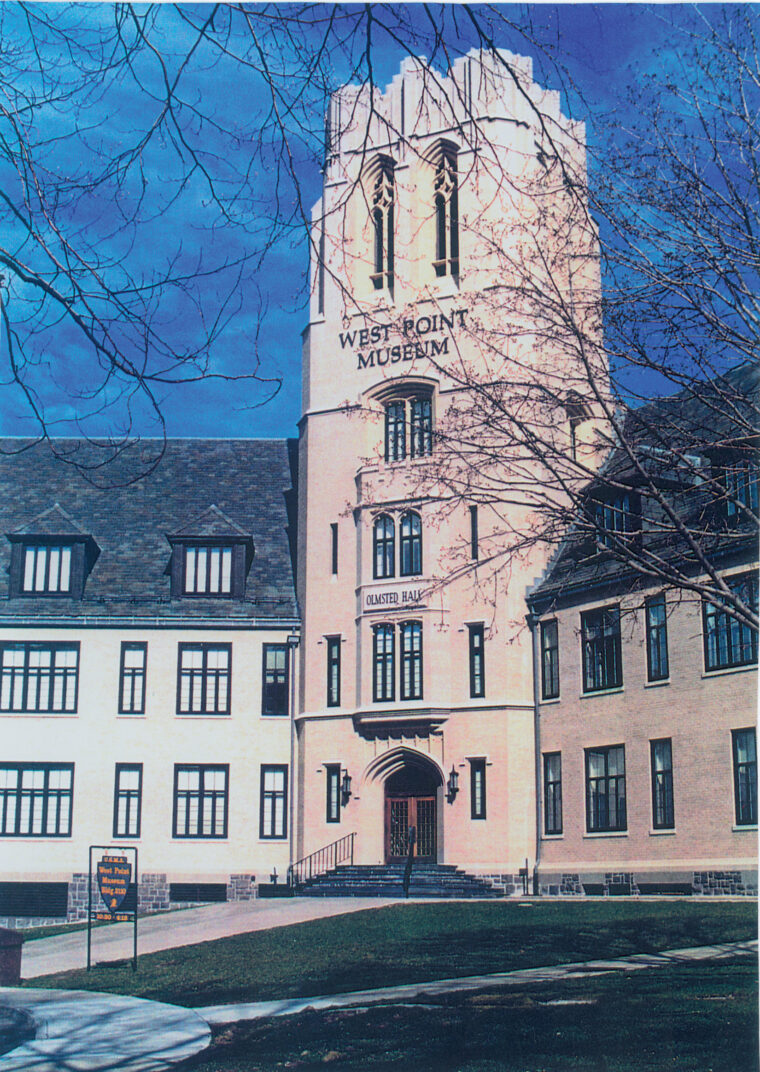

The museum is housed in Olmsted Hall, named for the founders of the (Maj. Gen.) George and Carol Olmsted Foundation. It is open seven days a week from 10:30 am to 4:15 pm, but is closed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day.

Although there are 45,000 items overall in the stunning and magnificent collection, according to Mr. Moss, “Less than 6 percent of the exhibits that we have are actually on display at any given time,” so that consequently there is a constant rotation of what is shown to the public.

Included among these are a German WWI Maxim gun, the “Fat Man” A-bomb case, two magnificent paintings depicting the D-day invasion of June 6, 1944 on the Normandy beachheads, a pistol belonging to Adolf Hitler, and the baton of his Reich Marshal, Hermann Göring.

Then, too, there is the first bazooka; General Jonathan M. Wainwright’s fountain pen, sabre, and Colt “Peacemaker” pistol, as well as the walking shoes and campaign hat of General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell from the little-known China-Burma-India Theater of WWII.

According to Mr. McAfee, “The 45,000 artifacts are displayed not only within the museum’s walls, but throughout the Military Academy’s buildings and grounds as well. The extent and diverse range of the collections span the history of warfare with internationally recognized holdings in the fields of arms, artillery, uniforms, and military art.

“The collections have been grouped into chronological periods that span the history of the Military Academy, the military history of the United States Army, and the history of warfare.”

Initially, both the Academy and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers were established when the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, signed into law on March 16, 1802 an act of Congress authorizing both, with the first students to begin classes the following July 4. The Engineers built roads, bridges, ports, and dams, as well as the famed Panama Canal. In 1816, the Academy’s Corps of Cadets adopted its famous War of 1812-style, gray, short-waisted uniform jackets, shako hats, and white trousers, and today the USMA colors are black, gold, and gray.

The crest on the face of the shako displays Greek symbolism: the helmet of the goddess Pallas Athena for learning and wisdom and the sword for the profession of arms that soldiers ply, indicative that all cadets will someday be officers.

According to Curator McAfee, “The origins of the Museum’s collections can be found with the deposit of captured arms and equipment from the

American Revolutionary War victory at the Battle of Saratoga in October, 1777. The artillery, shoulder arms, and accoutrements captured at Saratoga from the British Army were badly needed supplies for the patriot cause, and many were distributed for use of the Continental Army.

“Much, however, was also placed in storage at the fortifications at West Point, and after the Revolution, war trophies from Saratoga and other victories were shipped to West Point for storage and future use.

“Although the infant United States Army continued to use these stores from the Revolutionary War for years,” McAfee goes on, “the captured cannons and mortars were carefully marked and respected as trophies of war. Along with the Great Chain [which spanned the Hudson River to block British warships] and the fortifications, these war trophies became popular tourist attractions in the early 19th century.

“After the Military Academy was founded, these same trophies became training devices for the young Cadets, helping them to understand the military art. By 1843, military memorabilia were being placed in a non-public ‘Musee d’Artillerie’ in an academic area of the Military Academy.

“The Mexican War of 1846-48,” continues Curator McAfee, “added a large new group of military trophies to the inventories of the Army. The role of Academy graduates was generally recognized as vital to the successful conclusion of the Mexican War and, as a result, a presidential directive placed the captured flags of that conflict at West Point.”

Notes WPM Director Michael Moss, “This made West Point the official national repository of war trophies, and in 1852 [when Robert E. Lee was superintendent] it was further recommended that captured Mexican artillery also go to West Point. The decision to place these artifacts at the Military Academy included the judgment that West Point’s ‘local beauties, and the social and political interests which center here…’ would en- able the trophies to be ‘inspected by vast multitudes … from all sections of the nation.’

“Also, it was hoped,” continues Director Moss, “that ‘the influence of those trophies upon the imaginations of those impressionable and ardent youths who are to be the future defenders and heroes of their country’ would be of great value, so the Artillery Museum at West Point was expanded and opened to the public in 1854.”

Rejoins Curator McAfee, “Since 1854, the West Point Museum, as it is now known, has served as both college museum and public institution. Through the years, thousands of additional military artifacts have been added to the original collection of war trophies. Today, the West Point Museum’s holdings encompass the military history of the world and are routinely used to augment the military education of the Corps of Cadets.

“Since their opening, the public galleries have been visited by millions of Americans and foreign visitors and have been housed in several locations.”

Indeed, in all, there have been a total of five museum moves over the years, and during the period 1958-1989 it was located in Thayer Hall. After a $12 million renovation financed by the Olmsted Foundation opened in 1989, the WPM has resided in Olmsted Hall to the present, and today it is estimated that 336,000 visitors come to see the displays annually.

As the West Point Museum enters its third century of operation, Director Moss calls it proudly “the oldest and largest diversified public collection of militaria in the Western Hemisphere.”

Most likely it will remain so for many decades to come.

Towson, Md., freelancer Blaine Taylor is the author of three books on World War II and the designated author/editor of the forthcoming work Treasures of the West Point Museum.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments