By Roy Morris, Jr.

The North African sky was clear and cold on the evening of February 13, 1943, as American General Dwight D. Eisenhower strolled out into the desert at Sidi Bou Zid, an oasis village in central Tunisia. Newly promoted to full general just three days earlier, Eisenhower still wore the triple gold stars of a lieutenant general on his collar. Alone with his thoughts, the 52-year-old Kansan picked his way by moonlight across the boulder-strewn ground outside the village. A few miles to the east, looming ominously against the far horizon, he could just make out the jagged contours of Faid Pass. Beyond the pass, as Eisenhower knew only too well, the battle-hardened soldiers in Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s formidable Afrika Korps were moving quietly in the dark. A German attack was coming soon—the only question was where.

Eisenhower was worried—and with good reason. He had just completed a late-night tour of American positions at the front, and what he had seen was not reassuring. The grass-green troops of the U.S. II Corps, extended in a 50-mile line behind the Eastern Dorsal range of the Atlas Mountains, from Pichon in the north to El Guettar in the south, were lightly trained and lightly bloodied. Since landing at Casablanca, Morocco, and Oran and Algiers, Algeria, three months earlier as part of Operation Torch, the massive Allied invasion of northern Africa, the officers and men had fought only a few minor skirmishes with the unmotivated French defenders of the collaborationist Vichy government before moving eastward into Tunisia. The easy victories against the French had convinced the inexperienced American troops that they were an irresistible juggernaut. Eisenhower knew better. He had recently sent a circular letter to all subordinate commanders complaining about the men’s “deficiencies in training” and the failure of the senior officers to “impress upon our junior officers, on whom we depend in great measure, the deadly seriousness of the job, the absolute necessity for thoroughness in every detail.”

Eisenhower’s warning fell largely on deaf ears. As he motored along the front in a specially armored Cadillac, the career soldier, a 1915 graduate of West Point, saw continued signs of his men’s amateurish indifference to their own defense. Some troops had been in their new positions for days without bothering to lay a single mine or dig a single foxhole. With growing impatience, Eisenhower pointed out that whenever the Germans took up a defensive position, they immediately laid out a minefield, emplaced their machine guns, and had their reserve troops standing ready—all within the space of two hours. The Americans, on the other hand, were content to throw their backpacks onto the ground, stack their rifles in an untidy heap, unfasten their grenades, and head straight to the nearest village for a little rest and relaxation.

To Eisenhower’s dismay, the only person who seemed to be taking adequate steps for his self-defense was II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall, who had established his headquarters 80 miles in the rear at Tebessa, Algeria. In violation of standard Army doctrine that called for placing command posts near crossroads and within easy access to the front, Fredendall had kept a squad of 200 engineers busy for three weeks constructing an impregnable position for him in a remote canyon between two towering mountains at the end of a narrow, twisting, gravel road. Below the headquarters the engineers had blasted out a series of underground shelters for Fredendall and his staff. “It was the only time during the war,” Eisenhower recalled later, “that I ever saw a divisional or higher headquarters so concerned over its own safety.” Not wanting to embarrass Fredendall, Eisenhower had mildly cautioned the corps commander a few days before: “[O]ne of the things that gives me the most concern is the habit of some of our generals in staying too close to their command posts. Please watch this very, very carefully among all your subordinates.” But Fredendall had not taken the hint. He was still safely ensconced in his mountain aerie when Eisenhower returned on February 13, leading Ike to observe—uselessly, as it turned out—that “generals are expendable just as is any other item in an army.” Events would soon test the wisdom of Eisenhower’s maxims.

The only bit of good news—if it could be called good news—was that the pending German attack was not expected to fall on the American sector of the Allied line. Rather, as Eisenhower’s chief intelligence officer, British Brig. Gen. Eric Mockler-Ferryman, assured him repeatedly, the codebreakers at the ULTRA project had intercepted numerous Nazi messages indicating that Col. Gen. Jurgen von Arnim’s Fifth Panzer Army in northern Tunisia was preparing to attack the British First Army and Free French XIX Corps at Fondouk, at the far end of the American position. U.S. Brig. Gen. Paul Robinett, whose Combat Command B (CCB) of the 1st Armored Division was temporarily attached to the British sector, vigorously disputed this contention, telling Eisenhower when he visited Fondouk that CCB patrols had penetrated all the way across the Eastern Dorsal without running into any sign of a major enemy buildup. Robinett said he had reported the reconnaissance findings to his superior, British General Sir Kenneth Anderson, but Anderson had refused to believe him. Eisenhower did, and he promised Robinett he would do something about it the next day. By then it would be too late.

The shadowy eavesdroppers at ULTRA headquarters in London had been right about the German intentions, but only to a point. The Nazis were, indeed, planning to attack, but not at Fondouk. Instead, von Arnim’s army, spearheaded by the crack 10th and 21st Panzer divisions, was preparing to advance westward through Faid Pass, drive off the American defenders at Sidi Bou Zid, and await the arrival of Rommel’s Afrika Korps, which was to seize Gafsa on the Allied right and then swing northwestward to capture the Allied airfield at Thelepte. From there, Rommel would take control of the battle and further act as events demanded.

The two-headed attack was necessary for the simple reason that there were now two German commanders in Tunisia—von Arnim and Rommel—and two separate German armies. Von Arnim, a seasoned veteran of the Eastern Front, had landed at the northern port of Tunis in early December to organize the Axis defense of the vital Mediterranean beachhead. In the wake of the Allied landings during Operation Torch, Adolf Hitler had rushed thousands of reinforcements, mostly German, to Tunis from Italy and Sicily. There they awaited Rommel’s fabled Panzerarmée, which was in the midst of a remarkable 1,500-mile fighting retreat from El Alamein, Egypt, across the entire northern coast of Libya to the old French fortifications at Mareth on the Libya-Tunisia border.

The three-month-long retreat was a bitter pill for Rommel, whose earlier lightning successes had made him a legend on both sides of the war. Now, ill and depressed, the German field marshal hoped to link up with von Arnim’s forces and hold off the cautiously pursuing British Eighth Army long enough to permit an orderly evacuation of all German forces from Africa. In order to do so, he believed it was necessary first to inflict a defeat on the newly arrived Americans, whose presence threatened to cut off Rommel’s communications with von Arnim and possibly lead to a fatal encirclement by the combined American and British armies at Mareth.

The overall German commander in the Mediterranean was neither Rommel nor von Arnim, but Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, headquartered in Rome. On February 9, Kesselring flew to Tunisia for a high-level strategy conference with his two commanders. At the Luftwaffe air base at Rhennouch, midway between Tunis and Mareth, the trio met to finalize plans for the combined attack. It was a frosty conference. Rommel and von Arnim had not seen each other in 18 years, but the lengthy interval had not softened their mutual dislike. Rommel, the self-made son of a middle-class schoolteacher, did not disguise his contempt for the aristocratic von Arnim, whose own father had been a Prussian general. Von Arnim, for his part, was jealous of his new commander and scornful of his much-publicized counterpart, whom he viewed as overrated, overspoiled, and overly pessimistic. Kesselring, who had been on the receiving end of Rommel’s endless complaints for the past three months, largely shared von Arnim’s view, but he was inclined to bow to Rommel’s demands one last time. As soon as the new offensive was over, Rommel would be relieved of command and shipped home to Germany to recover his health. Von Arnim, expecting to inherit the Desert Fox’s army if not his legend, could afford to be patient. “Let’s give Rommel this one last chance of glory before he gets out of Africa,” Kesselring whispered to von Arnim before the meeting.

Besides the clash of personalities, the German battle plan was hindered by the lack of a clearly defined objective. Von Arnim, having seized Faid Pass on January 30, favored a limited attack through the pass, then a consolidation of his army’s gains preparatory to a thrust at the British and French positions at Pichon and Fondouk. Rommel, unaware of von Arnim’s more modest intentions, wanted to drive the Americans completely out of Gafsa and, if possible, exploit the initial attacks to seize the entire Western Dorsal as well. Kesselring, who should have known of von Arnim’s plans, sided with Rommel. “We are going to go all out for the total destruction of the Americans,” he said. “We must exploit the situation, and strike fast.”

Influenced perhaps by the crushing German defeat at Stalingrad six days earlier, Kesselring now envisioned a breakthrough victory in North Africa. “I think that after Gafsa we should thrust into Algeria,” he said, “to destroy still more American forces.”

Not even Rommel thought that was feasible, but he did foresee the possibility of a deeper penetration than von Arnim envisioned. The differing aims and aspirations, as well as the overall lack of communication between the commanders, would soon come back to haunt the Germans.

In a driving sandstorm the vanguard of von Arnim’s assault force rumbled through Faid Pass at dawn on February 14—St. Valentine’s Day. Their initial targets were a pair of high hills, called djebels, overlooking the road from Faid to Sebeitla. The northernmost position, Djebel Lessouda, was held by a battalion of the U.S. 1st Armored Division under the command of Lt. Col. John K. Waters, the son-in-law of Maj. Gen. George S. Patton. Waters had something of his famous father-in-law’s warrior mentality; after his men had won an easy victory over the French at the beginning of the campaign, he had cautioned them against over-confidence. “We did very well against the scrub team,” he said. “Next week we hit the Germans. Do not slack off in anything. When we make a showing against them, you may congratulate yourselves.” Leaving nothing to chance, Waters had tank patrols in motion each night to feel out the enemy’s intentions.

Unfortunately for the Americans atop Djebel Lessouda, a strong northwesterly wind the previous night had smothered all sounds of the German buildup. Major Norman Parson’s patrolling Company G ran headlong into the lead elements of the 86th Panzer Grenadiers and 7th Panzer Regiment about 6:30 am, and was quickly routed. Parson’s command tank was knocked out of commission early in the battle, and with it all radio communications with Dejebel Lessouda were lost. The carefully prepared artillery barrage that Waters and his engineers had prepared for the enemy was rendered inoperable before it began.

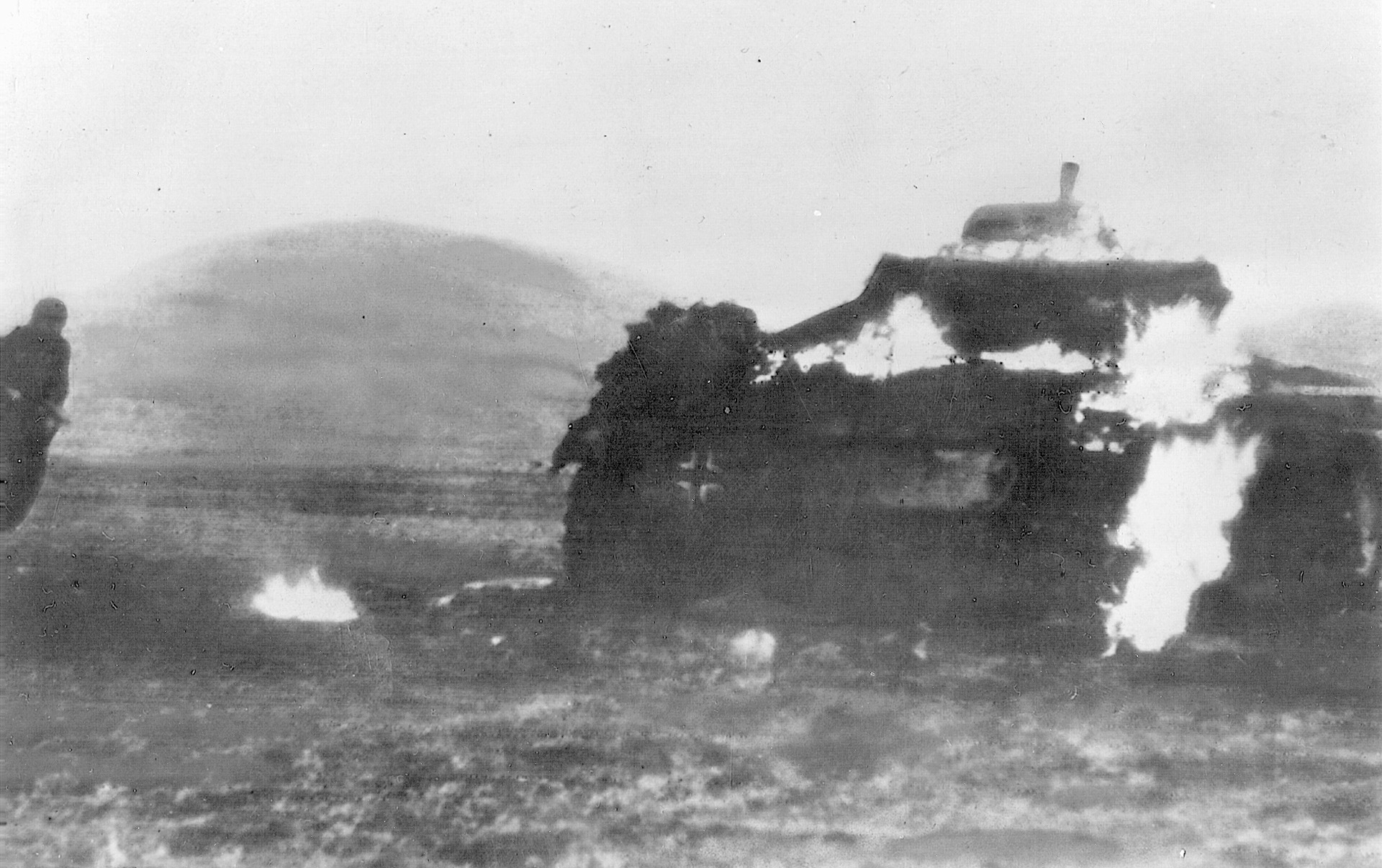

Waters realized soon enough that an enemy attack was under way, and he radioed for help to Combat Command A (CCA), seven miles south in Sidi Bou Zid. Tank Companies H and I of the 3rd Battalion, 1st Armored Division, under the personal command of Colonel Louis V. Hightower, hurried to the rescue. The Americans were riding M-3 Sherman tanks armed with 37mm guns. The M-3, with a range of only 1,800 yards, bore the distinctly unmilitary nickname “Honey.” The Germans had another name for it—they called the M-3 “Ronson,” after the cigarette lighter, because it burst into flames so readily. Arab nomads passing freely between the lines had been warning the Americans for weeks that the Germans had a powerful new tank in their arsenal. “Sure,” the GIs scoffed. Now, the men in Companies I and H learned that the Arabs had been right. Mark VI Tiger tanks, armed with 88mm guns, were mixed in with the more familiar 75mm-gunned Mark IVs. The new Tigers had a firing range twice as long as the American M-3s, and they quickly put that advantage to good use. The more powerful enemy guns exacted a heavy toll on the Americans. Burning and abandoned vehicles soon littered the desert floor.

Hightower’s own tank, a 75mm M-4 Sherman, engaged seven German tanks in a raging firefight. Radio Sergeant Clarence Coley took off his headphones and began passing artillery rounds up to the loader. “All the time we were firing at the Supermen [Nazis], they were not wasting any time,” he recalled. “We were getting it hot and heavy. I did not keep count but we received many hits on our tank. I could feel the shock and hear the loud noise as those projectiles bounced off…. Our luck finally ran out. A round got stuck in the gun, wouldn’t go in or come out…. [A]bout the same time, one of the enemy guns got a penetration in our tank. The projectile came in the left side, passing through the gas tank, ricocheting around and winding up on the escape hatch just behind my seat.” Coley watched in fascinated horror as the 88mm round stood on end, spinning like a top, with fire flaming out of the upper part like a tracer round. The inside of the tank immediately caught on fire. “Let’s get the hell out of here,” Hightower said.

The colonel and his crew scrambled out of the burning tank and set off on foot across the scorching desert. Aided by the smoke and dust kicked up by the battle, they made their escape. They were among the lucky ones. Of the 51 American tanks that had set out toward Djebel Lessouda, only seven remained operational at the end of the day. A similar number of halftracks, personnel carriers, and other vehicles also were lost.

As the first prong of the German attack poured through Faid Pass and cut off the American force at Djebel Lessouda, a second wing of attackers moved through Maizila Pass, 20 miles due south of Faid, and then divided into separate columns to envelop Djebel Ksaira, five miles southeast of Sidi Bou Zid, where another isolated force of Americans, infantry and engineers from the 34th Infantry Division under Colonel Thomas D. Drake, held a precarious toehold in the Tunisian hills. Tanks, armored infantry, artillery, and flak units from the 21st Panzer Division executed the complicated maneuver under the watchful eyes of division commander Colonel Hans Georg Hildebrandt. The German offensive moved with typical Teutonic precision, reuniting at noon at Bir el Hafey, 18 miles southwest of Sidi Bou Zid, and preparing for a final drive on the oasis settlement two hours later.

Inside Allied lines at Sidi Bou Zid, chaos and confusion reigned. Brigadier General Raymond A. McQuillin, commanding officer of CCA, received conflicting reports from division commander Maj. Gen. Orlando Ward, who was several miles in the rear at Sbeitla. At first, Ward did not consider the situation grave. He soon changed his mind as enemy infantry and artillery descended on the town early that afternoon. McQuillin pulled back to a new command post seven miles southwest of Sidi Bou Zid and waited for darkness to cover his retreat. Individual units and men, however, did not wait for dusk to leave the field. Throwing down their weapons and abandoning their vehicles, they set off for the rear in a dead run.

Eisenhower had just returned to Fredendall’s headquarters when the first reports of an enemy attack came filtering in from the front. Assured that it was a limited incursion, Ike left for his own headquarters at Constantine, Algeria, 300 miles away. By the time he got there, he learned to his dismay that he was facing a major crisis. Calmly, but with a sense of urgency, Eisenhower began dispatching reinforcements to the crossroads village of Sbeitla, an old Roman outpost where Ward had established a rallying point. Colonel William Kern’s 1st Battalion, 6th Armored Infantry, secured the town, and later that afternoon McQuillin and his badly cut-up CCA straggled into the new Allied line. Left behind were the 2,000 soldiers marooned atop djebels Lessouda and Ksaira, who could only watch as the plain below crawled with advancing Nazi soldiers.

Ward, who had seethed with anger when Fredendall broke up his division and sent part of it northward to serve under British control, immediately began formulating plans for a counterattack. On the morning of the 15th, Lt. Col. James D. Alger’s 2nd Battalion, 1st Armored Regiment led a force of 58 tanks, supported by infantry, artillery, and combat engineers, on a mission to rescue the Americans trapped at Lessouda and Ksaira. The attack began with parade-ground precision, rolling east in a straight line toward Sidi Bou Zid, 13 miles away. German dive-bombers soon disrupted the Allied advance, and Alger and his men found themselves rolling headlong into an ambush.

While the enemy planes harried them from above, Nazi artillery opened up along the northern flank, and columns of tanks enveloped them on three sides. Alger, asked to report his situation, replied laconically: “Still pretty busy. Situation in hand. Further details later.” Then his radio went dead. Alger was captured, and another 312 Americans were killed, wounded, or missing. Most of the supporting infantry was able to straggle back to Sbeitla, but another 54 tanks, plus 57 half-tracks and 29 guns, were lost in the rout. Before his capture, Alger had managed to shoot up the enemy’s reserve motor pool at Sidi Salem, and the fire and smoke from the burning vehicles, along with the dust kicked up by hundreds of lumbering tanks, obscured the battlefield. Ward, reporting the attack to Fredendall, could only say, “We might have walloped them, or they might have walloped us.”

By nightfall, it was apparent to all who had done the walloping. The infantrymen stranded atop the two djebels were left reluctantly to their own devices. Under cover of darkness, German infiltrators wearing captured uniforms rounded up a number of stray Americans, including Colonel Waters. Farther south, Colonel Drake and his men abandoned Djebel Ksaira and attempted to get away to the west, but quick-reacting motorized troops pursued and encircled them in a large cactus patch. Drake had no choice but to surrender himself and his 600 men. In all, nearly 1,500 Americans were taken prisoner at Sidi Bou Zid.

While von Arnim’s troops were beating back the doomed American counterattack, Rommel’s Afrika Korps entered Gafsa. The retreating Allies had paused only long enough to blow up their ammunition dump. Unfortunately, the massive explosion collapsed nearby Arab houses, killing 34 men, women, and children (another 80 were counted as missing). When Rommel rode into town himself the next morning he was greeted by cheering residents, who chanted, “Hitler! Rommel!” The German commander was unmoved by the welcome, but he quickly sized up the situation. With von Arnim in complete control of Sidi Bou Zid and the enemy in precipitate retreat on both fronts, a dual thrust at Sbeitla and Feriana, the next major village west of Gafsa, might open the way for a united assault on Kasserine Pass, the chief passageway through the Western Dorsal and the key to the enemy command center at Tebessa.

Rommel made a quick telephone call to von Arnim, telling his grudging counterpart that he was advancing on Feriana and urging von Arnim to continue driving westward. By mid-afternoon on the 17th, Rommel’s men had captured Feriana and rushed on to seize the abandoned Allied airfield at Thelepte. Reports indicated that the enemy was in a general retreat. The entire theater of operations was breaking open in a wondrous, scarcely believable way. “I feel like an old cavalry horse that has suddenly heard the bugle’s sound again,” Rommel exulted in a letter to his wife, Lucy. After Kesselring agreed to give him control of the developing German breakthrough, the Desert Fox opened a bottle of champagne—a rare indulgence for a man who typically abstained from alcohol.

Rommel’s elation was short-lived. It soon transpired that von Arnim, despite his earlier reassurances, had no intention of driving farther west than Sbeitla. Nor did he intend to send Rommel all his panzer units, as Kesselring had ordered. Instead, as von Arnim brusquely informed Rommel, he intended to renew his plan to attack Fondouk. In effect, he was moving away from Rommel, not toward him. Precious time was lost while Rommel attempted to clarify the situation. After repeated telephone calls between Rommel, von Arnim, and Kesselring, a compromise was worked out: Rommel would receive two panzer divisions, the 10th and 21st, from von Arnim, but he would no longer drive on Tebessa. Instead, he was to head for the Allied supply depot at Le Kef, 70 miles farther east, the better to support von Arnim’s long-delayed offensive. Rommel’s patience—never his strong suit—snapped. His aide, Alfred Berndt, recalled: “He could see that the successes we had obtained just weren’t being exploited fast enough and in the right way.” A golden opportunity, perhaps the last the Germans would have in North Africa, was rapidly slipping away.

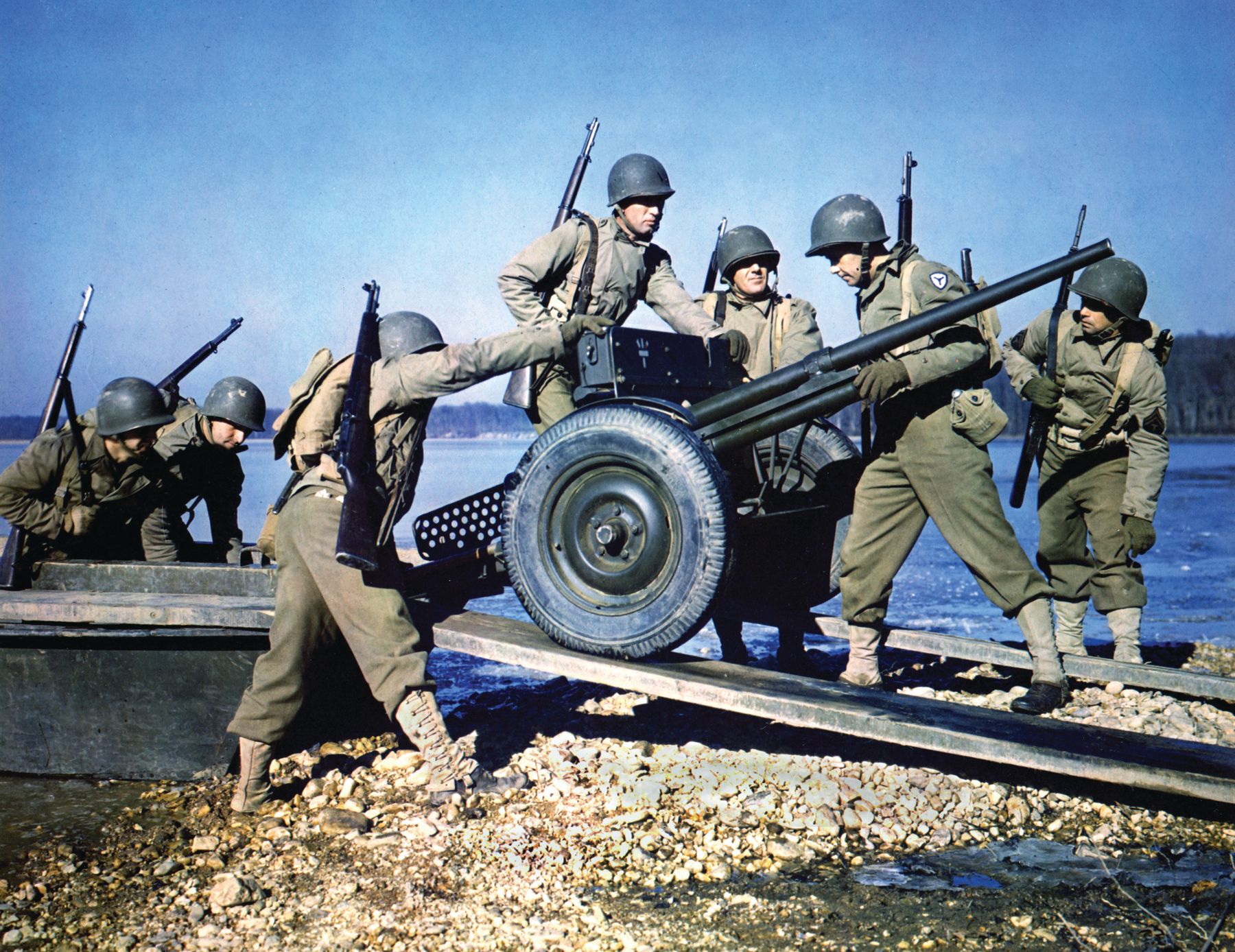

The Nazi command imbroglio gave the hard-pressed Allies valuable breathing space. With Eisenhower’s permission, the entire line fell back to positions behind the Western Dorsal, 50 miles to the west, blocking the key passes to Sbiba, Thala, and Tebessa. Considering the obstacles facing the soldiers—bad roads, intermingled units, driving rain, total darkness, and frighteningly effective enemy fire—the withdrawal went surprisingly smoothly, particularly for the inexperienced American troops who had just received a painful introduction to desert warfare at the hands of Rommel’s battle-seasoned veterans. Eisenhower reported to U.S. Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall: “Our soldiers are learning rapidly, and while I still believe that many of the lessons we are forced to learn at the cost of lives could be learned at home, I assure you that the troops that come out of this campaign are going to be battlewise and tactically efficient.” Moreover, said Ike, the men were “now mad and ready to fight. All our people, from the very highest to the very lowest, have learned that this is not a child’s game and are ready and eager to get down to business.”

Inevitably, recriminations began to be heard from within the American chain of command. Fredendall, who had rather tardily moved his command post from his mountain hideaway to the town of Kouif, midway between Tebessa and Thala, complained to Eisenhower, “[A]t present time, 1st Armored [is] in bad state of disorganization. Ward appears tired out, worried and has informed me that to bring new tanks in would be the same as turning them over to the Germans. Under the circumstances do not think he should continue in command…. Need someone with two fists immediately.” Eisenhower had no intention of removing Ward in the midst of a battle; he understood the great difficulties Ward had faced due to his division being split into various commands. Instead, Ike sent a trusted lieutenant, Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon, commander of the 2nd Armored Division, to advise Fredendall at II Corps headquarters and serve as “a useful senior assistant [during the] unusual conditions of the present battle.”

It would take Harmon four long days to reach the front. In the interim Rommel resumed his offensive. On the morning of February 19, he began a three-pronged assault on the main passes in the Western Dorsal. The Italian Centauro Division would “feel” toward Tebessa, on the Allied right; the Afrika Korps would drive toward Kasserine Pass, in the center; and the 21st Panzer Division would advance on Sbiba, on the enemy left. When Rommel could determine which force was making the most headway, he would throw in the 10th Panzer Division to add weight to the attack.

The night before, in perhaps his only positive move during the entire battle, Fredendall had telephoned Colonel Alexander Stark, commander of the 26th Combat Team, a mixed unit of infantry, artillery, and engineers, and instructed him: “I want you to go to Kasserine right away and pull a Stonewall Jackson.” No sooner had Stark reached the front the next morning than Kampfgruppe DAK, under the command of Brig. Gen. Karl Buelowius, began storming the pass. Unlike some of the American commanders, Stark had already sparred with the Germans along the Eastern Dorsal, and he quickly arrayed his men in an effective defensive position on the heights overlooking the mile-wide mouth of the pass. Colonel Anderson Moore, commanding the 19th Combat Engineers, laid mines along the entrance, then placed his men, armed with howitzers, machine guns, and rifles, on either side of the gap. Then they waited.

At 10:15 am, 35 to 40 truckloads of German infantry unloaded southeast of Kasserine Pass and headed straight for the heights. Two veteran Panzer grenadier regiments led the attack, which was observed firsthand by Rommel and Buelowius. The rainy, foggy conditions precluded the use of dive-bombing air support, and the poor visibility also limited the Nazis’ ability to counter the American artillery fire. Buelowius, embarrassed by the slow advance, committed another Panzer regiment and assured Rommel that he would win control of the pass by the end of the day. Rommel, who intended to make his main attack at Sbiba, was unconcerned. He left Buelowius to his own devices and headed north to check on the progress of the 21st Panzer Division at Sbiba. As he drove along the road, the field marshal saw numerous wrecked American trucks “with dead men sitting at the wheels, evidently shot up by low-level air strikes.” The macabre sight filled him with renewed confidence.

Five miles south of Sbiba, Rommel encountered the 21st Division commander, Colonel Hildebrandt, who gave him a quick briefing. The attack was not going as well as he hoped, Hildebrandt said, owing to a deep enemy minefield and the surprisingly stiff defense put up by American and British forces on the heights overlooking the gap. Rommel, raging at the “dawdling” and “inefficient” Hildebrandt, called off the attack at Sbiba and rushed away to locate the 10th Panzer Division, which von Arnim had been instructed to send him, to get it started toward Kasserine Pass. There he would make his main thrust the next morning. He found the division resting comfortably near Sbeitla. “Those fellows are all far too slow,” Rommel complained. He was infuriated to learn that two of the division’s battalions were missing, along with two dozen of the new Tiger tanks. Von Arnim had held them back, against orders, to support his own assault on Fondouk. Rommel would receive no more reinforcements.

At Kasserine Pass, Buelowius renewed his attack on the morning of February 20. Again the going was slow. The Germans’ heavy vehicles bogged down in the soft ground, and continued rain and fog once more grounded the fearsome Stuka dive-bombers. Buelowius committed the Italian 5th Bersaglieri Battalion, a crack mountain-climbing unit, to drive the Americans from the heights, while two additional Panzer regiments smashed their way through the pass. Rommel, back on the scene, raged at Brig. Gen. Fritz von Broich, commander of the 10th Panzer Division, demanding to know where the division was. Broich explained awkwardly that he was waiting for an infantry battalion to attack first. “Go and fetch the motorcycle battalion yourself, and lead it into action too,” the furious field marshal ordered. He was tired of listening to lame excuses.

The Allied defense wavered, then broke under the weight of the German advance and a flurry of six-barreled Nebelwerfer rocket launchers, which could deliver 80-pound rockets at a distance of four miles. The Americans defending the hills overlooking Kasserine Pass broke for the rear, leaving behind 22 destroyed tanks and 30 captured half-tracks on the valley floor. By now Kesselring had come up to the front, and he and Rommel briefly conferred while the German columns moved through the pass and branched out onto the open plain beyond. Rommel was worried about reports that Montgomery’s Eighth Army had reached the outskirts of the Mareth line and begun skirmishing with the rear guard there. He and Kesselring agreed that the current offensive was running out of time.

The next day the Germans again advanced but were repeatedly slowed by Robinett’s Combat Command B, which even Rommel grudgingly admitted was employed “very skillfully.” More and more Allied reinforcements arrived on the scene, including British and Senegalese troops. American artillery fire ripped jagged holes in the German lines. Buelowius called for air support, but the antiaircraft half-tracks of the 443rd Coast Artillery Battalion responded with a curtain of .50-caliber machine-gun fire, shooting down two dive bombers and driving off the rest. Unfortunately, the jittery artillerists also shot down five Allied airplanes that inopportunely flew into range. Farther to the north, British tanks from the 26th Armored Brigade engaged the 10th Panzer Division on a ridge just south of Thala. The panzers pierced the British lines but were thrown back by a wild, hand-to-hand counterattack. Exhausted, the combatants withdrew for a distance of a thousand yards and stood regarding each other warily, like fought-out fighters staring across a boxing ring.

That same afternoon American Brig. Gen. LeRoy “Red” Irwin’s 9th Infantry Division artillery arrived on the scene, having made a four-day, 800-mile-long march from western Algeria to the Tunisian front. Although exhausted, the Americans set up their field pieces on the heights overlooking the Thala line. The next morning, when 10th Panzer rolled forward, its tanks were met by a thunderous artillery barrage. Von Broich, who had already endured a dressing down by his field marshal, a nerve-racking attack at the front of his motorcycle battalion, and a brutal melee with steely British defenders, wavered. Thinking the enemy artillery fire was the signal for an Allied counterattack, von Broich suddenly stopped his advance. The last opportunity for a decisive German breakthrough was lost.

Back at the northwest mouth of Kasserine Pass, Rommel was simultaneously handed news of von Broich’s checkmate and an intercepted message from the British commander declaring, “There is to be no further withdrawal under any excuse.” Down to his last 250-300 kilometers worth of fuel, Rommel immediately gave the command to fall back.

Later that night, Harmon arrived at Fredendall’s headquarters outside Tebessa. The first thing Fredendall wanted to know was whether Harmon thought the headquarters should be moved to the rear. “Hell, no,” Harmon replied. Then Fredendall handed the new arrival an envelope placing Harmon in command of “the battle then in progress.” “Here it is,” said Fredendall. “The party is yours.” Relieved of command—and relieved in general—Fredendall went to bed and slept straight through for the next 24 hours.

It took Harmon until late the next afternoon to determine that Rommel was truly in retreat. He organized a belated counterattack, which amounted mainly to following the Germans at a gingerly distance. In short order, the Allies reoccupied Sbiba, Kasserine Pass, Thelepte, Feriana, Gafsa, Sbeitla, and Sidi Bou Zid—all the places they had abandoned so precipitately a few days earlier. Then they had been running from both the German Army in general and Erwin Rommel, the legendary Desert Fox, in particular. Now, having learned a hard but necessary lesson in the art of war from a modern master, the Americans were no longer “our Italians,” as the British and French had cruelly joked. They were battle-tested and battle-ready. In the long run, Kasserine Pass would prove to be the rare type of instructive defeat that was, in its way, more valuable than a victory.

Roy Morris, Jr., of Chattanooga, Tenn., is also a noted author on the American Civil War. Among his books are biographies of General Phil Sheridan and author Ambrose Bierce.

“ An abandoned Bristish Sten gun carrier sits nearby as Field Marshal Erwin Rommel surveys the ground before elements of his vaunted Afrika Korps.”

It is not a sten gun carrier. The author might think it is a Bren gun carrier but, regrettably, it is not. It is Italian, possibly an L3/33 variant.