By Mark Carlson

Since the early days of the Great War, when pilots and observers brought rifles and pistols into the skies to shoot at enemy observation planes, the world of air combat has been a rapidly changing arena of technology and innovation.

The first real fighters flew in 1915 carrying what is generally known as “rifle caliber” machine guns using .30 caliber (7.62mm) ammunition, much the same as a deer hunter. The light bullets were effective well into the 1930s against the unarmored and fragile planes of the time.

But by the beginning of World War II, the heavier construction of warplanes, along with their increased speed and power, necessitated a drastic change in military thought. What to arm an airplane with? What caliber? Should it be cannon or machine gun? What was the primary mission and target? How many rounds could or should a plane carry? What rate of fire, effective range and how many guns were needed?

All these and more questions were constantly under consideration by the War Department as the United States drew closer to war in Europe and the Pacific. Fortunately, a great deal of information on the aircraft armament of British, German and Japanese planes was available for analysis. A careful review of tactics and pilot accounts revealed that most air combat took place within a 1,000-yard range, and often at speeds of less than 300 mph.

On the Allied side, the British had been highly successful with the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire against the Luftwaffe. The Hurricanes were most often sent against the bombers during the Battle of Britain, and the Spitfires took on the fighter escort. While these were the two primary roles for fighters, both used essentially the same armament.

The tough Hurricane had one of the most varied weapon loads in history. More than a dozen variants were produced, most often carrying the Browning .303 machine gun, the same caliber carried in First World War biplanes.

The Hurricane MkIIA used 12 Brownings with an average of 300 rounds per gun. The .303’s small size allowed for more rounds to be carried but the Hurricane was limited in range so a compromise between fuel and ammo had to be reached. Other models carried Hispano MkII 20mm cannon, as did the Spitfire. Col. Steve Pisanos, who had served in No. 71 RAF Eagle Squadron, commented on the Spitfire’s guns. “I never had any victories in the Spitfire. But I destroyed a lot of locomotives. Those little .303 machine guns weren’t much use but the cannons worked fine. They fired pretty slowly. I could hear the individual shots. We could select between gun and cannon.”

On the Axis side, the Luftwaffe primarily used fighters for bomber escort and air defense. The Messerschmitt Bf-109s were often armed with two rifle caliber machine guns in the cowling, two 20mm cannon in the wings and sometimes a 15mm or 20mm cannon in the propeller hub. The wing cannon were largely abandoned by the time the Bf-109G was developed.

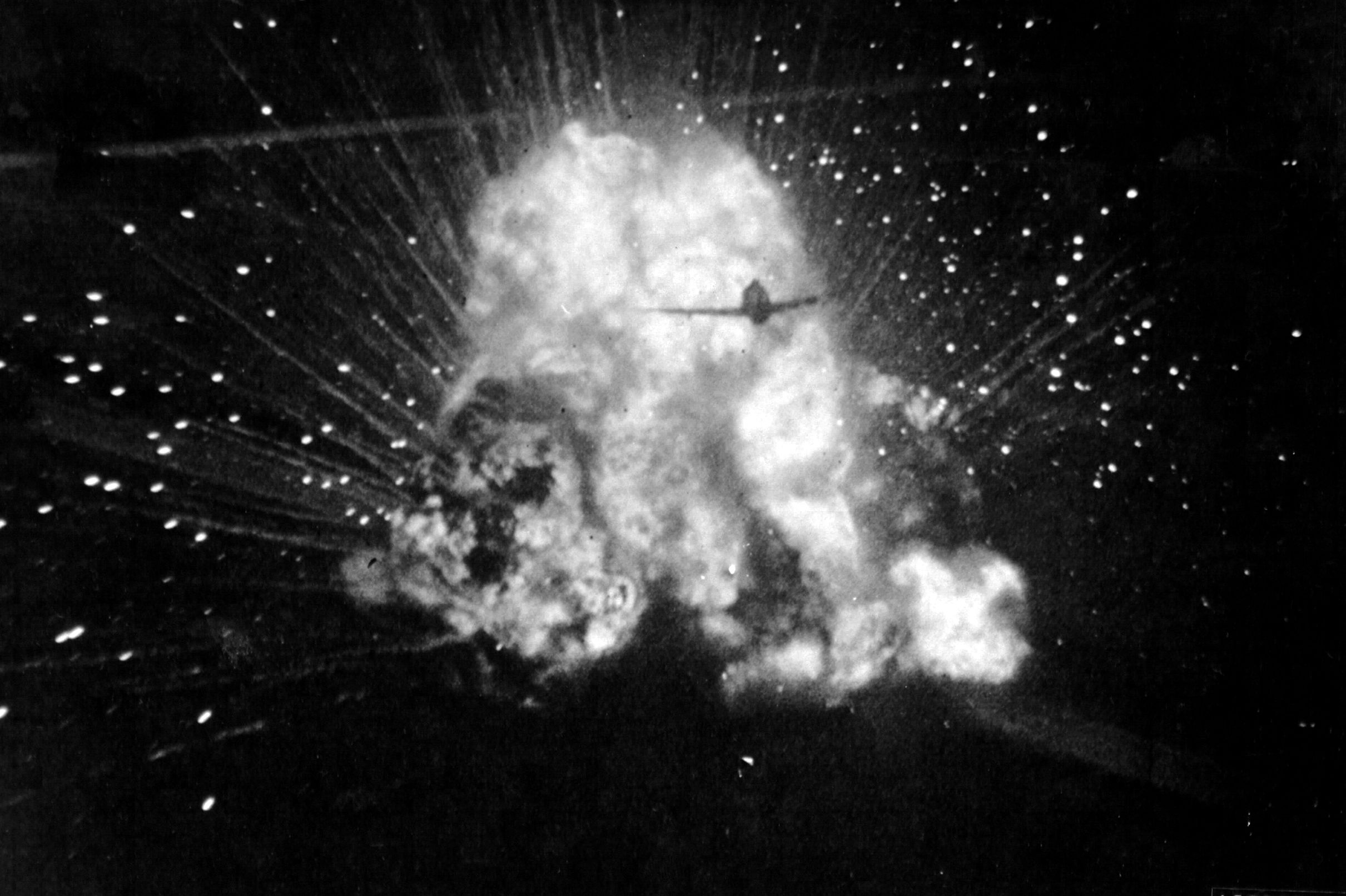

This made for a great deal of firepower when used against American and British bombers, particularly when they were unescorted. But the heavy punch afforded by the cannon meant less ammunition and slow rate of fire, so pilots were unable to rake their targets and do maximum damage. Dogfighting was most often done from close range, at rapidly changing angles, where light machine guns were often more effective than cannon.

On the other side of the world, the Japanese were in a war of conquest deeply laced with the code of Bushido—the way of the Samurai. Pilots trained in the warrior code were to attack and bring down their opponents without mercy. Their targets were often other fighters encountered during the pacification of China and the Allies over the Pacific. Japanese pilots considered them a worthy enemy. Their fighters were the modern version of the Samurai sword, and to be used only for worthy opponents. But that same code was what made their planes extremely vulnerable to enemy fire. The Mitsubishi A6M Zero was a light, highly maneuverable fighter with large control surfaces and low wing loading. But in the effort to reduce weight, the Zero—as with most Japanese front-line fighters and bombers—carried no armor or self-sealing fuel tanks.

A Zero could outrun any plane in the U.S. inventory in a dogfight but it was very delicate nonetheless. At altitudes above 15,000 feet the Zero’s large wings and low power were a liability, resulting in less maneuverability. An American Naval aviator once observed that “trying to hit a Zero was like swatting a mosquito with a baseball bat. But when you hit it, the damn thing came apart. The trick was in hitting it.”

The A6M’s primary armament were two Type 99 20mm cannon in the wings and twin 7.7mm machine guns, again rifle caliber, in the cowling. The small caliber wasn’t able to penetrate armor and often did little more than punch holes in a plane’s skin. The cannons’ heavy punch was offset by the limited ammo load of 60 rounds. On early A6M models the cannon barrels were cut short to minimize drag, diminishing muzzle velocity and range.

Saburo Sakai, Japan’s fourth-ranking ace, commented on the cannon. “Our 20mm cannon were big, heavy and slow-firing. It was extremely hard to hit a moving target.” Japanese pilots often used the Zero’s superior maneuverability to rake the enemy with the 7.7mm machine guns—then strike with the cannon to score the kill. “Our opponents were tough,” Sakai said.

American fighter doctrine intended to use fast and heavy planes in hit-and-run attacks. The method was originally developed by the Luftwaffe, in contrast to the Japanese preference for dogfights. In fact, studies proved that maneuverability was the least important ability for a fighter to have. What was important was a high power-to-weight ratio, high-altitude performance and long range. Rugged construction was also a U.S. standard.

Last on the list of needed attributes was firepower. A fighter is a flying gun platform, the aerial equivalent of an old West gunslinger. Unlike Britain, Germany or Japan, the United States was not likely to have to contend with home defense from high-altitude, heavy bombers as neither Germany nor Japan possessed any.

The USAAF, Navy and Marines were looking at both air defense of bombers and offensive use of the proposed front-line fighters. Later, the concept of ground attack and infantry support was added to the equation. It came back to the choice between rifle caliber machine guns or explosive cannon shells. The smaller guns had a much higher cyclic rate, often more than 1,000 rounds per minute, but they also lost much of their killing power after a few hundred yards, particularly in a chase when the target was moving in the same direction. A machine gun weighed about 25 lbs; the large cannon, 200 lbs.

When all these factors were considered, some albeit in hindsight, American air policy chose a “middle ground” between heavy firepower with a slow rate of fire, and smaller caliber with more ammunition carried per gun. A series of single-caliber machine guns was a more effective means of filling the air with lead and steel than a mixed cannon/machine gun combination.

The caliber finally adopted was the .50 (12.7mm) cartridge, made in several variants, such as armor piercing, tracer, incendiary and jacketed lead. Developed during the First World War, long before it was recognized as the perfect caliber for air combat, the .50 was made for anti-tank use in an age when tank armor was far thinner than it would be a generation later. The steel-tipped armor-piercing round may not have had an explosive head but it was capable of boring holes in pilot armor and cracking engine blocks. A hailstorm of steel from six machine guns would be more effective than a pair of cannon with a slower rate of fire.

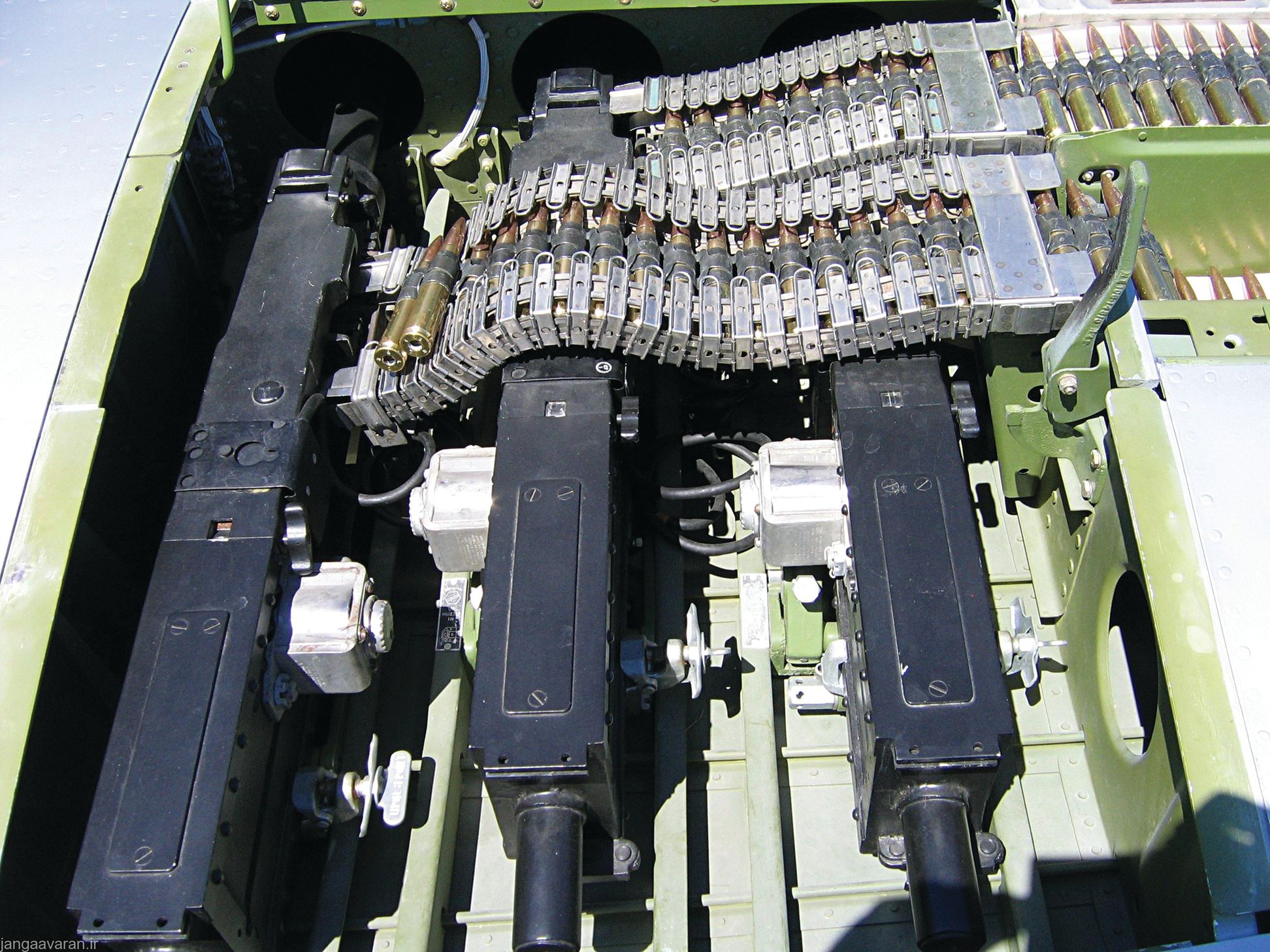

The incredibly versatile M2 Browning was developed by John Browning in 1918, just as the war in France was winding down. Air-cooled, the Browning was perfect for the role of a defensive and offensive air-to-air weapon. The robust machine gun was made in several variants and the one for aircraft was the ANM2 for “Army/Navy” use. It was officially designated the Browning Machine Gun, Aircraft, Cal. .50 ANM2 (Fixed) or (Flexible).

With a muzzle velocity of over 2,900 feet per second and an effective range of more than 2,170 yards, the M2 Browning was carried in nearly every single U.S. warplane from bombers to patrol planes to fighters. When fitted onto a flexible mount the ANM2 served as a defensive weapon. The aircrews of thousands of B-17s, B-24s, B-25s and other planes swore by their “wonderful fifties,” often giving them pet names. The bristling black muzzles of Brownings in Liberators and Fortresses gained a healthy respect from Axis fighter pilots and it was only through constant innovation and determination they were able to approach the deadly envelope of flying steel.

Several American aircraft companies competed for the lucrative military contracts early in the war. This resulted in many weapon variants. Thus there were a few warplanes with armament that fell outside the norm.

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning’s twin engines and central fuselage was uniquely suited to carry a 20mm cannon in the nose, surrounded by four Browning machine guns. Likewise the Bell P-39 Airacobra, having its engine mounted behind the pilot via a long driveshaft to the propeller afforded a space for a tank-busting cannon and two .50 caliber machine guns, along with four .30 caliber machine guns in the small wings. The P-39 was certainly the most eclectic of the fighter concepts. It is not surprising that it had little success in any theater other than as a Lend-Lease fighter for the hard-pressed Soviet Air Force in its desperate battles against the German invasion.

The typical, if such a word can be applied here, American fighter carried only one caliber of weapon. In multiple fixed wing mounts for fighters the ANM2 carried the fight to the enemy’s planes, troops, trains, trucks and war industry. Having the same guns and calibers in nearly every single warplane made supply and maintenance far easier to manage.

The electrically-fired ANM2 was fitted with a lighter barrel than the standard M2, which increased cooling and cyclic rate. The ANM2 could fire, at maximum, 750-850 rounds per minute (rpm). The fighter’s slipstream cooled the barrels. The cyclic rate varied from gun to gun, depending on barrel wear, lubrication and ammunition type. The lighter armor-piercing and tracer rounds slowed the rate of fire slightly.

Since much aerial combat took place in nearly subzero temperatures, electric heaters were fitted around the breech to keep the oil from freezing. On many fighters the inboard guns had blast tubes to minimize the muzzle flash and powder burns on the fuselage. The perforated sleeve of the .50, being lighter and shorter than those on ground M2 models, was the same as on a ground-mounted Browning .30 caliber.

Armorers loaded the guns and charged them—pulled the bolts prior to takeoff.

Colonel Pisanos, after his time in the RAF, joined the USAAF and became a double ace in the 4th Fighter Group.

“Both the P-47 and P-51 had a switch on the panel which electrically armed the guns,” Pisanos said. “When we crossed into enemy territory the flight leader signaled, ‘Guns up!’ We never took off with them on.”

Four, six and eight guns were the most common armament for the Navy and Army planes. Early on, four guns was considered adequate, but increased engine power allowed an increase to six in the case of the P-51 Mustang and F4F Wildcats. Early Vought F4U Corsairs also had four guns but this was quickly increased to six.

The design of each type of aircraft made it necessary to find solutions which allowed for the maximum firepower. In the case of the Mustang, the slim laminar-flow wing’s profile was too low for the high breech mechanism of the Browning. North American’s elegant solution was to tilt the guns almost 45 degrees to one side on its long axis—lowering of the gun’s profile enough for it to fit inside the wing.

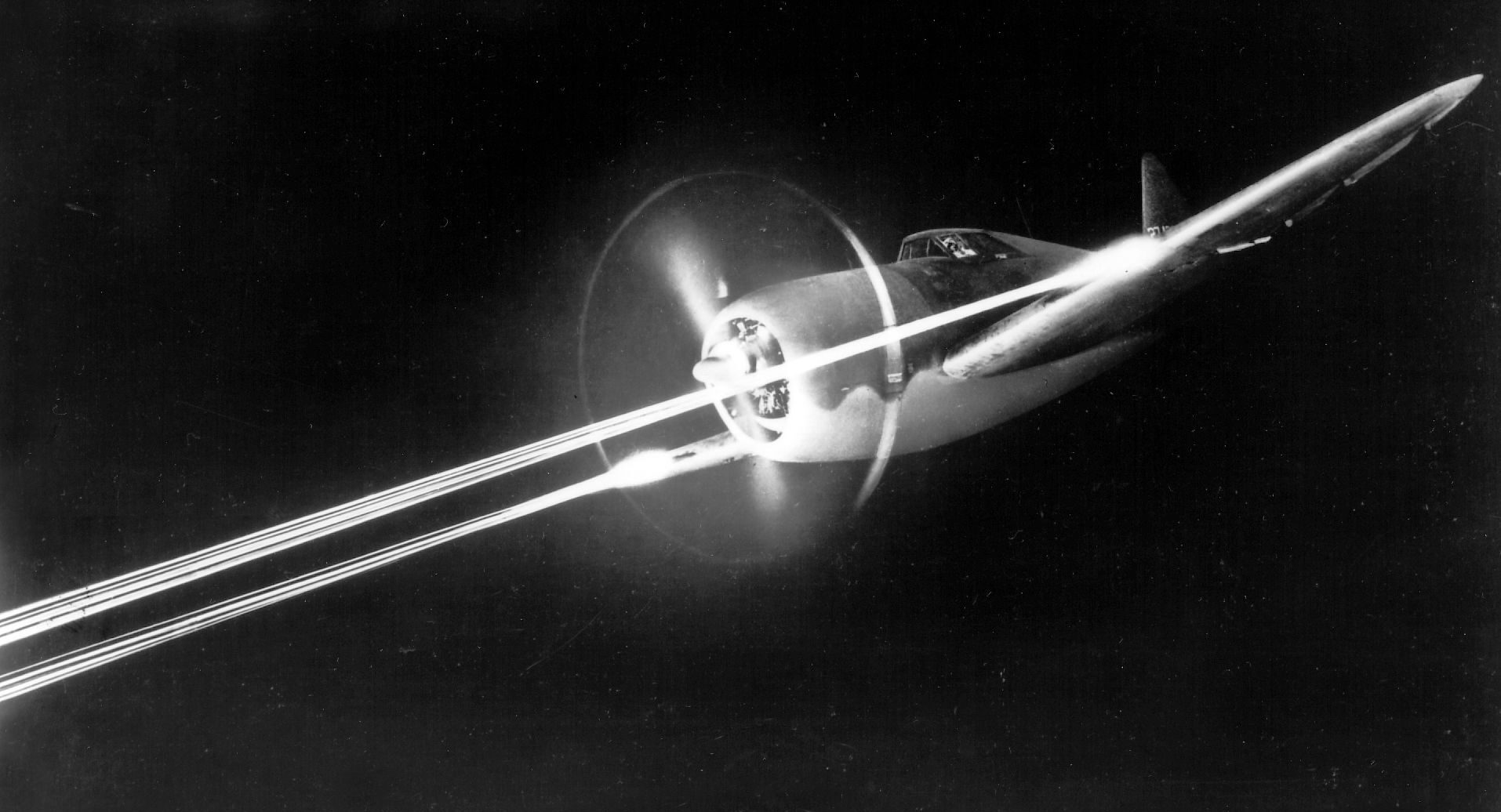

With its huge Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engine, the beefy Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was able to carry eight Brownings and a total ammo load of 3,200 rounds, far more than any other U.S. or Axis fighter. Firing at about 12.5 rounds per second per gun—nearly 100 shells a second—the Thunderbolt could fill the air with steel.

“The P-47 was a fantastic ground-attack plane,” Pisanos said. “Those eight guns just ripped apart anything they hit.”

In every fighter the cartridges were fed from the ammunition trays along carefully placed belt feeds. Spent cartridges were ejected from the bottom of the breech and fell free from ports located on the underside of the wing.

Colonel Don Blakeslee, the C.O. of the 4th Fighter Group was learning to fight with the P-51B Mustang after his Fighter Group changed over from the Thunderbolt. Pisanos recalled an encounter Blakeslee had with a Messerschmitt. “Me-109 pilots avoided making sharp right turns, because the aircraft would often tumble over and go into a spin. They usually made left turns while evading. Anyway, one day Blakeslee was behind a 109, and it dove to the left to evade. He stayed with it in the tight diving turn and hit the trigger. A few shots came out and the guns stopped. He tried again and again. Nothing. Of course the German got away.”

Blakeslee returned to base and chewed out his ground crew. “They could hear him screaming in Washington,” Pisanos chuckled. “Fighter Command and Materiel Command were called in to look at it. What had happened is that in a steep turn with many G’s the gravity-fed belts were failing to feed the rounds. So that’s when the Ordnance people designed an electrically-driven motor on the belts for the P-51 and P-47.”

Despite Hollywood depictions, fighter pilots didn’t have unlimited ammunition to waste—hosing it at a hapless Zero while maintaining a witty repartee with the doomed pilot. At most, depending on the aircraft, the total firing time was just over 30 seconds. This is based on the rpm of 750-850 at maximum sustained fire. However pilots most commonly fired in short bursts of a few seconds.

For instance, the P-51D Mustang, carrying six Brownings, was loaded with 400 rounds for the four inboard guns, and 270 for the two outboards. The total load was 2,140 rounds. This was enough for 35 seconds. “We never used all our ammo in one long burst,” Pisanos said. “We always tapped the firing button for a few seconds at a time. When you saw puffs of smoke from your hits, then you kept it up.”

The ammunition was, from research the author conducted at the San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives, and interviews with fighter pilots, often a sequence of 1 Tracer, 1 Armor Piercing, 1 Incendiary and 2 Ball. While this varied depending on the fighter group/squadron protocol, the most common was to have a single tracer as every fifth round, providing a visible streak as an aiming aid.

“We didn’t use tracers in the 4th Group,” Col. Pisanos noted. “All our rounds were ball or armor-piercing. But a lot of other groups used them.”

The range of the “kill zone” was a matter of personal preference. Some pilots preferred to have all the shells converge on a small area about a foot in diameter 1,000 yards away.

“My guns were aimed at about 500 yards,” Pisanos said. “That was just about right for me. When I saw the target dead center in my gunsight ring I hit the trigger.”

Others wanted a broader “basket,” having some guns zeroed in at 500 yards and others filling a narrowing cone out to 1,000 yards. It depended on the target, the plane’s capacity and how the pilot fought. Some put themselves in close and hammered the enemy plane when it had no room to maneuver. This was the tactic employed by the top Luftwaffe ace, Erich Hartmann, who scored 352 victories. Surprisingly, Hartmann avoided dogfighting. The “hit and run” attack became U.S. fighter doctrine throughout the war.

The final outcome of the air war was decided as much by superior pilot training as advanced aircraft. But as far-reaching as those factors were, the standardization of armament greatly aided ultimate victory.

It would be easy to assume the era of the machine gun and/or cannon ended with the birth of the jet plane. But nothing could be further from the truth. After all, the North American F-86 Sabre carried the same armament into the skies over the Yalu River in Korea as its predecessor, the Mustang. Machine guns and cannon continued to be used well into the jet age, superseded only when the air-to-air missile became a reliable weapon. Even so, today’s high-technology multimillion-dollar jets with sophisticated avionics and weapons still carry a gun. The Lockheed-Martin F-22 Raptor carries a 20mm M61 Vulcan rotary cannon with 400 rounds, just as the M2 Browning had in the 1940s. But that’s where the comparison ends. The Vulcan is a “last-ditch” weapon, not the primary means of bringing down a foe. At the Vulcan’s 6,000 rounds per minute, the ammo will only last five seconds.

The barrel jacket of thre aircraft .50 cal M2 was not the same as that of the ground-mounted Browning .30 caliber. (air-cooled M1919). It was longer and of a larger diameter.

I don’t recall the P-51’s guns being tilted, but then I only worked on the D model. The photograph conforms to my memory of upright guns.

“That was just about right for me. When I saw the target dead center in my gunsight ring I hit the trigger.”

only works for a tail chase. Deflection shooting requires leading the target.